|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Australian Federal Police - Platypus Journal/Magazine |

International Policing Conference 2001

The International Policing Conference 2001 held in Adelaide on March 6-8 was designed to bring together leaders from international police communities along with distinguished speakers from a variety of related fields to discuss how global crimes are being dealt with at a local level.

The AFP provided a number of speakers and delegates to the conference, while former AFP General Manager National Operations, Alan Mills provided an overview of the role of civilian police in United Nations peacekeeping activities.

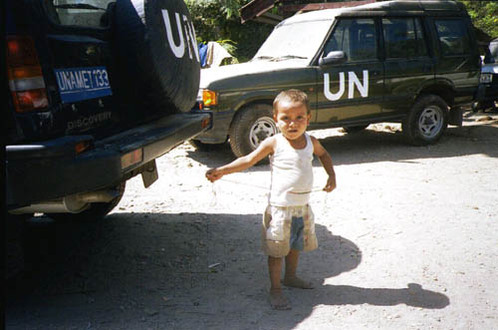

I served as Commander of the Australian Civilian Police contingent to Cyprus in 1989–91, and as the first civilian police Commissioner to East Timor for the United Nations Assistance Mission to East Timor (UNAMET), and for the United Nations Transitional Authority East Timor in 1999 (UNTAET). The observations I make throughout this article are based on my own experiences in those roles, and in managing AFP's international operations supporting the various UN missions.

In June 1945, representatives of 50 nations signed the new United Nations (UN) charter, effectively replacing the League of Nations as an organisation dedicated to maintaining world stability and peace. This act reflected the optimism of a collection of leaders weary of war.

In May 1948, the Security Council established a field operation to supervise the truce in the first Arab-Israeli war. Thirty-six military observers arrived in the Middle East as the first United Nations peacekeepers. More than half a century on, hundreds of thousands of individuals, military, civilian police and other civilian experts in their fields, have served in 53 United Nations peacekeeping operations. More than 1650 military and civilian peacekeepers have died while serving in United Nations operations.

The “traditional” United Nations peacekeeping roles continue with the military providing personnel and structure that remains the backbone of most operations. There is an increasing trend for civilians to participate in peacekeeping operations and this includes electoral experts, police, human rights monitors, de-miners, specialists in civilian affairs and communications and observers.

UN peacekeeping operations initially made no provision for a civilian police capability. Peacekeeping functions centred on the role of the military in bringing peace to fractured states and rebuilding the state into a democratic society.

Much of the planning and implementation of peacekeeping operations was a military responsibility. The introduction of civilian police was seen as a subservient and minor function that the military could absorb as part of the overall operation. There was little recognition of the different functions and approaches of the police role in its assistance to the mission.

Peace operations have evolved since the 19th century from colonial interventions, counter-insurgencies, occupation, military assistance to civil administrations, frontier operations and multinational operations. Since the end of the Cold War, many peace operations have involved varying degrees of “policing activities”, ranging from supervising indigenous police agencies to actual law enforcement.

“Police operations”, in the peacekeeping sense, have often been used in activities “other than war”. For example Britain's “Imperial Policing” in her colonies in inter-war years, as well as conflicts such as the Korean War (1950-53) and the Gulf War (1991), were known as police operations, and the force established by the UN for the Sinai (1956) was known as a police force. The United Nations coined the term “civilian police” or CivPol to distinguish the difference between the civilian and military police components employed within missions.

The term CivPol originated when the UN Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus (UNFICYP) was established in 1964. Jose Rolz-Bennett, U Thant's special representative, suggested including a military police element in the new force, but U Thant's military adviser, Major General Indar Jit Rikhye, opposed the idea on the basis that military police normally function only in support of the military. The Force Commander, Indian Lieutenant-General P S Gyani, proposed a civilian police component instead.

On April 4, 1964, CivPol became operational in Cyprus. By June of that year, 173 civilian police officers had arrived, 40 Australians, 40 Danes, 40 Swedes, 33 Austrians and 20 New Zealanders.

CivPol in Cyprus operated in national units with each contingent being assigned responsibility for one district. Sometimes officers were exchanged between contingents, on a voluntary basis, to share experiences and standardise procedures. This is of course counter to the currently adopted method of mixing or blending contingent detachment personnel.

In those early times the civilian police mandate entailed monitoring, advising and training with some minor investigations being undertaken to identify participants not conforming to the UN agreements. More recently, civilian police have taken on the added role of mentoring the local police. Policing is now considered crucial in re-establishing the social, political and economic conditions within the fractured State.

In the same decade, civilian police were deployed in United Nations operations in the Congo and progressively from that time have increased their role, culminating in the 1988 UN mission in Namibia where it was recognised that CivPol's presence was crucial. By mid 2000, about 9000 civilian police from more than 70 countries were participating in 10 UN missions. Civilian police have predominantly staffed some recent missions.

In Haiti, civilian police helped rebuild a new Haitian National Police as is being undertaken currently in East Timor. In Croatia, a UN Civilian Police Support Group was established to monitor the actions of the Croatian police in Eastern Slovenia, and to encourage respect for the rights of residents and returnees alike. In Bosnia and Herzegovina more than 1600 police officers from 42 countries served with the UN International Police Task Force, which forms part of the United Nations Mission (UNMIBH) in that country. Their tasks include monitoring the performance of local police, conducting investigations, and providing guidance aimed at building a multi-ethnic police service respectful of the rights of all the country's people, regardless of ethnicity.

In Kosovo, as many as 4700 UN civilian police have been charged with maintaining civil law and order, as well as developing future police for the territory.

As it stands today, civilian police deployments to UN peacekeeping missions include:

|

UNMIBH (Bosnia/Herzegovina)

|

2057

|

|

UNTAET (East Timor)

|

1640

|

|

MINURSO (Western Sahara) UN Interim Administration

|

31

|

|

KOSOVO

|

4162

|

|

UNAMSIL (Sierra Leone)

|

60

|

UNMIBH and UNTAET are about 10 – 15 per cent under strength due to constraints being experienced by contributing countries.

In early 2000 UN CivPol and other officials met in Spain to re-examine the management, structure and policies for CivPol that would be relevant to its emergence as a major UN component for use in current and future deployments.

For a peacekeeping operation to be successful, four clear requirements are essential. There must be a genuine desire on the part of the warring parties to solve their differences peacefully. The operation must have a clearly defined mandate, and there must be strong political support from the international community. Finally, the resources necessary to achieve the operation's desired objective must be available and deployable.

Peacekeepers often support complex civilian and military functions essential to maintain peace, and to begin the reconstruction and institution building in societies devastated by war. Peacekeeping mandates have historically ranged from keeping hostile parties peacefully apart, to helping them to work peacefully together. As tasks have become more varied and complex, proportionately larger numbers of civilians have joined military personnel as UN peacekeepers.

Ultimately, international intervention should improve local capability of self-government so the level of intervention should be reduced gradually in response to local improvement. The emphasis is on fostering, reforming, or re-establishing existing structures, including local security and law enforcement institutions. This is also necessary to relieve the military intervention forces as quickly as possible from policing tasks.

Both the military and the CivPol have important roles to perform in peacekeeping, but it is important to understand that they are different and complementary, and that a stable and sustained resolution of the problems of a fragmented state will not be achieved unless there is an appropriate contribution by both the military and police, each operating in its specialist role.

Australian police have been part of the UN Force in Cyprus (UNFICYP) since its establishment in 1964, in an effort to bring an end to the hostilities.

The AFP's role in Cyprus can be likened to community policing without the normal recourse of arrest and presentation of evidence in a court of law. The AFP provides 20 personnel on rotation, with continued involvement being assessed on the renewal of each six-month mandate.

Recent changes to the organisational structure have seen the creation of an integrated civilian police component (UNCIVPOL), with the AFP members now living with and working alongside members of the Irish police contingent in stations across the island

Rebuilding a country structure is a long-term proposition, one in which both the military and police have proper roles. “Peace = order + justice” describes the necessary balance between the various components of society. The military provides the “order” and the police and the judiciary provide the “justice”. In the same way, civilian police cannot substitute for the military in circumstances where the latter must provide a stable environment or act as a deterrent force.

Colonel Larry M Forster, the Director of the US Army Peacekeeping Institute said: “the macro and micro levels of security (represented by the military and police components, respectively) are interactive, and both are necessary for the success of an operation as a whole”.

The military is not well adapted to and prefers to avoid civilian policing functions, which typically produces an “enforcement gap” during the peace operation.

Policing is predicated on the attributes of non-negotiable force and discretion. The routines of all policing, especially at the operational level, are characterised by discretion — the use of discretion being an important key to policing. Discretion marks a very important difference between the police and military roles.

The Civilian Police role in a fragmented State includes:

• providing a stable and secure environment;

• assisting in dismantling the old instruments of repression;

• establishing and maintaining a law enforcement and criminal investigation capability;

• selecting and training new members of an indigenous police service, which will ultimately take over the law enforcement role from UN Civilian Police;

• undertaking investigations and collecting evidence appropriate to the prosecution of alleged serious violations of human rights;

• assisting in re-establishing the criminal justice system and civil administration, including the court system and the jails; and

• confidence building with the civil community by operating impartially to enforce the law.

CivPol, or indeed any of the vital UN elements, should not be withdrawn before these objectives are largely achieved, or there is every chance that the state will again fragment, requiring further UN or international intervention.

The international community has become increasingly aware that without fair, functioning and transparent criminal justice systems, of which law enforcement agencies are an essential part, there is little chance of meaningful lasting peace in divided communities. Today's peacekeepers are often required to serve in a complex, often tense domestic conflict, largely characterised by civil war and ethnic rivalry. The roles of peacekeepers have grown to include a wide range of confidence building measures such as holding of elections and restructuring government institutions. Recognition is now being given to the valuable contribution of civilian police in infrastructure re-establishment, and the development of indigenous police services, criminal justice systems, the judiciary and the jails.

Where the United Nations intervene or provide peacekeepers to a host country, the Secretary-General chooses the Force Commander, and the Civilian Police Commissioner, and asks member states to contribute troops, civilian police or other personnel. The lead-time required to deploy a mission varies largely on the ability and the will of the member states to contribute personnel. At the start of the mission an advance team, including core staff of CivPol members who will make up the mission, must arrive in a timely fashion.

The nature and scope of the peacekeeping mission will often determine the progress of the operation. This will also impact on the makeup of the staff required to support the mission.

Civilian police and military personnel remain members of their home service, but serve under the operational control of the United Nations during deployments. They must conduct themselves according to the international character of the mission.

On October 28, 1998, the UN asked countries contributing to peacekeeping operations to send no civilian police officers or military observers under the age of 25 years, and to send troops over age 21, and never under 18. The parameters were intended to ensure that only experienced, mature and well-trained people serve as peacekeepers.

People serving in peacekeeping operations require skills to work in a chaotic and complex environment that also then requires a broad police and military skills base, and a well-developed ability to be flexible and patient in trying situations. Recent experiences in East Timor and Cyprus have shown that people who are rigid, inflexible, perfectionist or over controlling will experience some difficulty performing a peacekeeping role (Jacob 1999).

Those people should:

• have a demonstrated capacity to perform the duties;

• have a knowledge of the United Nations' role and function;

• have the demonstrated ability to exercise self-discipline, and a willingness to accept a military-style working and living environment;

• have knowledge of the ethnic culture relevant to the host country and a sound knowledge of the history surrounding the United Nations commitment;

• have the demonstrated ability to be culturally aware and tolerant and sensitive in dealing with difference;

• be aware of the requirement to adhere to, and implement, the mission directives, orders and procedures;

• be fluent in the language of the mission;

• be conversant with the UN Charter of Human Rights; and

• have a range of technical skills such as map reading. The ideal civilian police officer should also be able to demonstrate:

• leadership qualities;

• prior experience;

• 8 years service; and

• high order negotiation skills.

CivPol officers will be required to operate independently, often in small teams and in remote locations where communications with head office via telephone or radio are not ideal. For these reasons flexibility and initiative are further qualities for civilian police members.

Prior to the arrival of the mission it is very useful for the commissioner to identify individuals with leadership experience, while recognising the need for an equitable distribution of roles and responsibilities. It should be noted that there is an extremely wide distinction in levels of expertise and management styles, which sometimes can be exaggerated, particularly in pre-mission resumes.

The flow on effect of this service, is of course, that the government of the contributing country benefits by the return of officers who are more rounded, worldly and tolerant, and who will be a more valued asset to the community which they serve.

As commissioner, and this point is also relevant for other senior CivPol officers, it is imperative that, on the ground, you embrace all available players to include all facets of the mission. Staff composition is important in this regard. The selection of the right person or people with the proper skills mix for the relevant task for particular roles is important in achieving an effective balance in the head office team, and hence to the regional teams. For example, key roles such as administration, logistics, training and communications must be in place at the outset of the operation if the contingent is to ‘hit the ground running'.

Formalising the structure of the contingent and the various detachments is made more difficult because not all contributors will arrive at the same time. The capacity of the country to release personnel is a factor to be considered in planning stages of the operation. When they do arrive, many will have varying degrees of experience and ability. Their stated rank may be inconsistent with their previously stated skills, meaning that at the end of the day they may not be appropriate for the position initially identified. Many will not be suitably equipped for the mission even though great pains are taken to advise member states of the type of equipment required.

There are many missions where staff arrive in climactically inappropriate uniforms, with a lack of bedding and other necessities.

• Some countries' CivPol representatives turn up in military uniform, including camouflage gear which closely resembles the uniforms of the protagonists – with only their blue berets and country identifying patch to distinguish them.

• Issues of recognition creates some difficulty in CivPol developing trust and cooperation with the local community.

• To overcome this I believe the UN should develop a unique CivPol uniform for all civilian police to wear when participating in a peacekeeping operation.

The mission statement and any parameters pertaining must be clearly understood by each CivPol officer.

Internal training is required to hone the skills of the participants in:

• Terms and conditions of service in the peacekeeping operation;

• Discipline and the procedures to be applied where an officer fails to act in the appropriate way;

• Radio procedures;

• Driving and driver testing (particularly as it pertains to local conditions and laws);

• Map reading and other navigation skills;

• The culture and history of the conflict; and

• Mission dynamics and strategies.

This approach develops consistency in the overall running of the operation, and ensures that all CivPol officers are operating in essentially the same way, applying the same methodologies and procedures. It also gives the training staff the ability to independently assess the qualities of the individuals and groups.

Employment Management Plans specifying mission objectives should be considered for issuance to senior CivPol members. At the conclusion of their tour of duty the degree of success in meeting such objectives would be a benchmark in finalising or determining members' reports.

The early establishment of a clearly defined Joint Operations Facility (JOF) will ensure, if properly established and used, that all parties have a clear understanding of issues relating to the mission, and the circumstances consuming the time of the other UN elements.

Daily, and sometimes more frequently, briefings in which a senior person, nominated by the officer-in-charge from each element of the operation, should provide an overview of their team's activities for the day, incidents and intelligence and forecast of future needs and implications.

In the early stages of any mission, it is extremely advisory to develop a mechanism that encourages the various UN elements to gather and report on individual and collective progress of outcomes.

The Joint Operations Facility should:

• be located at a central position (HQ);

• represent all the various elements, through a representative, either full or part time, depending on their individual contribution;

• be chaired by, and made up of, senior officers with the manager of the facility being reflective of the stage of the mission; and

• be able to assimilate sensitive political or military reporting.

Where there are regional outposts they should be represented in a like manner, reporting as required to the JOF.

Where appropriate, one or more of the protagonists (parties to the conflict), should be invited to have representatives in the JOF.

Hotline connections should be established to the various departments, areas, countries so that issues arising in the briefing that require urgent attention can be dealt with in a timely way.

From my experience there cannot be enough communication between the UN and the parties to the conflict. Trust and confidence usually comes slowly, and any variance of a common approach can be seized upon in an effort to deflect further commitment. It is therefore essential that all elements of the UN staff sing from the same sheet of music.

There is great scope for UN missions to fail if communications and understanding are not across the board, at all levels. CivPol, together with other UN groups, must continually be conferring with all parties. The involvement of the UN Public Relations Group to internally and externally communicate policy and issues becomes an important factor.

Training for peacekeeping missions needs to include a range of skills that might not necessarily be directly involved in keeping law and order.

The United Nations consider that police on peacekeeping operations should be unarmed when performing their role. An unarmed presence has the greatest chance of success in gaining the respect of the local community and in promoting the safety of the CivPol officers themselves. The influence and effectiveness of civilian police is based on moral authority rather than the threat of force.

The question is, whether being armed would enhance the performance of civilian police or whether it would cause additional risks and hinder them in carrying out their duties?

The use of force, and in particular firearms, presents difficult legal consequences that are not generally addressed in United Nations Mandates or Status of Forces Agreements. For example, if an armed Civilian Police officer discharged a firearm causing injury or death, what authority has jurisdiction? The international composition of Civilian Police leads to varying national standards and regulations in the use of firearms. Most contributing countries have adopted the United Nations covenant requiring the minimum use of force by civilian police officers, which really amounts to the use of a firearm only to protect one's own life, or that of another person in imminent danger. However, police from some countries have a much wider interpretation of the use of firearms, and this could have a serious impact on the overall objective of the mission.

The issuance of sidearms to CivPol should only be taken as a last and extreme measure. That issuance must be consistent with the mandate criteria and preferably in agreement with the parties to the conflict.

In my experience, the issuance of a sidearm for CivPols raises the bar in terms of the visual acceptance as a peacekeeper, and increases the likelihood of the member becoming a target. In any case, when compared against the array of military type weapons usually carried by the parties to the conflict, the presence and capacity of a sidearm is totally disproportionate.

In stressful situations, some CivPols may be inclined to draw their sidearm, an action that could antagonise the parties (who may be looking for such an opportunity), and therefore increase the likelihood of an escalation of the incident.

The absence of weapons assists in clearly projecting a more positive image to the parties to the conflict and the community generally. In most cases it engenders respect that paves the way for a more positive communication process.

For those CivPols operating under executive powers (physically running a domestic policing service) I still have reservations about routinely arming such members. If the circumstances are so threatening to their presence the most obvious stance would be for the military component to resume their presence in force until a more peaceful situation prevails. The UN Commissioner should perhaps have the delegation to have sidearms available for issuance in accordance with the existing circumstances.

Planning is the most important consideration throughout the life of the UN peacekeeping operation. As a mission progresses, you have to continually plan for every contingency that may arise in the next phase/stage, and in doing so you must be aware of the strengths and make up of replacement staff. While planning skills are an essential component of military officer's training, there is generally a fundamental lack of such training within police departments.

There is a tendency for many of those skills to be acquired with experience or specific recruitment. It is therefore important to ensure that police officers with planning skills are identified and employed accordingly. In the absence of police officers, civilian planners attached to police departments should be utilised.

As the mission changes, so does the emphasis on personal skills needed to service those changes. The individual qualities required at the start vary considerably from those required for the re-birth of institutions, and the design and philosophies of emerging bodies. In the initial deployment of UN personnel to East Timor (UNAMET) the emphasis was to create the circumstances for an election to be held. When the community overwhelmingly voted for independence, the subsequent emphasis (UNTAET) was directed towards creating a new nation, including all the attendant organs of state.

The rebuilding of specialised policing units may require more consideration being given to employing experts from the various fields eg. Forensic Science, Information Technology, Administration etc. The UN should look to civilians versed in those fields to augment police officers. To have a positive effect of institutional change, there should be a consistency in delivery of many facets of police training, and policy and legal development. It would be detrimental to the development of any organisation if regular changes in direction occurred in accordance with the methodology or practices employed with each new contingent's arrival. It would be preferable to request donor countries, with established expertise to provide a continuous and consistent support team for between 3–5 years to avoid developing an organisation with uncommon policies and procedures. It is preferable to identify any key positions with appropriate job specifications to ensure that donor countries may assess their abilities to meet such specifications. This will also assist staff at UN headquarters to more accurately convey personnel requirements to donor countries.

The CivPol team should aim to map out stages of the projected mission with various phases, including:

• Establishment;

• Interim period; and

• If required, rebuilding society – by mapping out an inventory of infrastructure.

Developing an inventory of those matters which can logically be deduced will flow from the mission – particularly if the CivPol role embraces the creation of a viable justice system, including courts, judiciary, police and prisons.

Any planning not embracing a complete justice system will fail to deliver a sound and workable law and order program.

Planning should also establish an inventory of the status quo of each of those elements, done openly and if correctly categorised it will give a starting point to provide some degree of continuity. In East Timor, almost all of the staff, together with their records and equipment, departed the country. Nearly all buildings were destroyed. By reference to the previously gathered material, a plan from a previously known base could be formulated.

Unlike the military the standard CivPol staffing arrangement is for contingents to be blended. This means that each detachment will have officers from various countries serving in it and because of that, it is important to find the right mix of skills, level of experience and expertise.

There are advantages and disadvantages in this arrangement. The matter is discussed within the UN from time to time. Some contributing countries prefer to keep their staff together as a team. From my perspective it is highly desirable to maximise the spread of staff according to their various qualities and levels of expertise. It needs to be clearly stated that many countries contributing to CivPol operations, provide personnel of varying standards, sometimes at a standard less than those of their police counterparts in the conflict zone. It is therefore important to staff according to balance and strength so that the overall effort reflects the UN contribution in kind.

In essence then, what the UN should do, is blend individual strengths into workable teams, notwithstanding issues of differing diets, work-practices, culture, religion and experience.

It is important to develop a rapport with the principal parties to the dispute and insofar as CivPol is concerned, to concentrate on meetings with police counterparts. In the first instance it will be highly desirable to gain an insight into how the protagonists view the historical and contemporaneous factors creating and sustaining the conflict.

It is also most useful to establish where the policing community stand and what their own judgements or leanings appear to be. Equally CivPol should exercise discipline in expressing, at least initially, their views to any of the parties until they have absorbed all of the facts. The protagonists will take many opportunities to denigrate what they perceive is UN interference, and any thoughtless public utterances may only set back the negotiation process. It is desirable to establish a rapport with the various authorities and, that statements to the media, if at all should be moderate and measured. I have seen many media reports, purportedly given by UN officials, antagonise one or more parties to the conflict and this has resulted in one case, to action being planned to assassinate that UN official. In most cases these issues require a light and delicate touch for trust to work in both directions.

Many agreements, taken at a local level, are over ridden by higher authority because officials are not authorised to speak on behalf of their government, so that agreed policies don't eventuate. It is useful to commit to paper any agreements, allowing for the fact that the contents may vary before formal endorsement. Any written agreement should be widely distributed so that all parties clearly understand the substance.

While you may make an agreement with another party it will not necessarily be lasting:

• You might make inroads, but the person you are dealing with may not have the authority to unilaterally agree; but

• You must come to some agreement about the level of exposure to publicity/the media you or they are comfortable with; and

• Be aware some of your utterances may be used against you. Each side will use the media to their own advantage and may say things that are not true. In dealings with the various parties it is often useful to make social calls on the various parties without an agenda requiring specific discussions. Casual contact with an absence of defensive repartee can be most positive in developing relationships. Accordingly when parties take positive initiatives, a word or two of praise can engender some added momentum to the process.

In any mission it is advisable to nominate a person responsible for the compilation and maintenance of a contemporaneous account of CivPol activities. This role could be given to a UN ‘Political Officer' who would frequently be involved in CivPol activities, and could independently de-brief officers as they move around or depart the mission. Debriefs are an essential exercise. The volume and quality of insight that flows from a properly conducted debrief will enable better planning and implementation in future deployments.

Psychological assessment and care are important in ensuring the well being of CivPol officers. Many countries pay particular attention to this service as a number of deployments may be conducted in stressful and sometimes dangerous situations. In the circumstances surrounding the violence that occurred in East Timor following the declaration of the ballot, many death threats were received by police officers. They witnessed a great deal of carnage and experienced feelings of utter hopelessness by their inability to help and protect local East Timorese people. The reality of this exposure has left many of those CivPol officers traumatised.

"If the UN didn't exist, they would have to invent it"

There are currently about 9000 police serving with the UN, but there are questions yet to be answered in considering the most useful contribution civilian police can make to UN peacekeeping operations, including how the situation with regards the good and the poor contributors can be improved.

Police are funded from the public purse so there is an onus on the Government to ensure value for money – it follows that mature, experienced police go into CivPol contingents.

The UN is currently very thin with strategic thinking and so it is incumbent on senior officers serving with UN contingents to identify measures to enhance CivPol operations specifically, but the overall UN effort generally. The Report of the Panel on United Nations Peace Operations, the Brahimi Report, provided a comprehensive assessment on deficiencies in the current arrangements and, more importantly, identified solutions.

A number of the report's recommendations accord with matters I identified during my term, particularly as Commissioner for UNAMET and UNTAET, and which I have raised in this article. It is, I think appropriate to finish by identifying some of the more important recommendations.

The UN Security Council unanimously adopted the Report of the Panel on United Nations Peace Operations, the Brahimi Report, by Resolution 1327 (2000).

The Secretary General commissioned the Panel, made up of individuals experienced in various facets of conflict prevention, peacekeeping and peace-building, to assess the shortcomings of the existing system and to make frank, specific and realistic recommendations for change. The Panel's recommendations focus on politics and strategy, as well as operational and organisational areas of need. Each of the recommendations contained in the report is designed to remedy a serious problem in the strategic direction, decision-making, rapid deployment, operational planning and support, and the use of modern information technology.

First and foremost, the Panel supports a doctrinal shift in the use of civilian police, and related rule of law elements in peace operations emphasising a teams approach to:

• upholding rule of law;

• upholding respect for human rights;

• helping communities coming out of a conflict to achieve national reconciliation;

• consolidation of disarmament;

• demobilisation and reintegration programs;

• flexibility for heads of UN peace operations to fund “quick impact projects” that make a real difference to the lives of the people in the mission area; and

• the better integration of electoral assistance into a broader strategy for the support of governance institutions.

The number of recommendations that specifically impact on CivPol, or demonstrate recognition of the increasing importance of CivPol in international interventions is encouraging.

Some matters of concern that I endorse are;

• It is essential to assemble leadership of a new mission as early as possible at UN Headquarters, to participate in shaping the mission's concept of operations, support plan, budget, staffing, and Headquarters mission guidance. The Secretary-General compile, a comprehensive list of special representatives force commanders, civilian police commissioners, their potential deputies, potential heads of other components of a mission, representing a broad geographic and equitable gender distribution.

• United Nations standby arrangements system (UNSAS) be enhanced to include several multi-national, brigade sized forces and enabling forces, created by member states, to better meet the needs of robust peacekeeping forces.

• The Secretariat send a team to confirm the readiness of each potential troop contributor to meet the prerequisite United Nations training and equipment requirements for peacekeeping operations, prior to deployment. Units that do not meet the requirements must not be deployed. The same should apply to civilian police contingents intended to make up part of the peacekeeping operation.

• A revolving ‘on-call list' of about 100 experienced, well qualified military officers, carefully vetted and accepted by the Department of Peace Keeping Operations (DPKO), be created within UNSAS.

• Parallel lists of civilian police, international judicial experts, penal experts and human rights specialists must be available in sufficient numbers to strengthen rule of law institutions as needed, and should be part of UNSAS.

• The establishment by member states of enhanced national pools of police officers and related experts, earmarked for deployment to United Nations peacekeeping operations, to help meet the high demand for civilian police and related criminal justice/rule of law expertise in peace operations dealing with intra-State conflict. Member states to consider forming joint regional partnerships and programs for the purpose of training members of the respective national pools to UN civilian police doctrine and standards.

Like a variation of a Voltaire quote, “If the UN didn't exist, one would have to invent it.” As with the presence of crime, human conflict will always be a reality with domestic and external disputes arising in many parts of the world.

Although this conference is being held in the very peaceful environment in Australia, one only has to glance to the north, north-east and north-west to identify many areas that have major points of conflict. Hitherto stable countries like Papua New Guinea, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Fiji and the Solomon Islands have joined others in the region where conflict and major breaches of human rights have a more ingrained history.

To break any cycle of conflict the UN must be in a position to be invited to provide an intervening group equipped with a viable mandate.

Any representation of civilian police in such a group should perform their duties commensurate with their experience and the terms of the mandate, but equally as important as good neighbours and responsible citizens of the world.

• Broar, Harry and Emery, Michael, Civilian Police in U.N. Peacekeeping Operations, Institute of National Strategic Studies, pages 1-17 http://www.ndu.edu/

• Dahlstrom, Timothy, Strategic considerations for the development of Australian Federal Police in support of peacekeeping operations, Presented to the Australian Defence Force Peacekeeping Centre, International Peacekeeping Seminar, July 1999

• Dziedzic, Michael J, Peace Operations and the New World Disorder, Institute of National Strategic Studies, pages 1-8

• McFarlane, John and Maley, William, February 2001, Civilian Police in United Nations Peace Operations: Some Lessons from Recent Australian Experience, Australian Defence Studies Centre, Canberra

• Monk, Richard, Keeping the Peace, International Police Review, May/June 2000, pp 39-41

• Penrose, Jeff, September 2000, Peace support operations and policing: an explosive human skills mix, Platypus magazine: the journal of the Australian Federal Police No 68 Sep 2000, pp 14-20

• Report of the Panel on United Nations Peace Operation, The Brahimi Report, 21 August 2000

http://www.un.org./peace/reports/peace_operations/docs/summary.htm

• Schear, James A and Farris, Karl, Policing Cambodia: The Public Security Dimensions of U.N. Peace Operations, Institute of National Strategic Studies

• Schmidl, Erwin A, Police Functions in Peace Operations: An Historical Overview, Institute of National Strategic Studies

• United Nations peacekeeping:-Preface

http://www.un.org/Depts/dpko/dpko/intro/intro.htm

http://www.un.org/Depts/dpko/dpko/intro/1.htm

http://www.un.org/Depts/dpko/dpko/intro/2.htm

http://www.un.org/Depts/dpko/dpko/intro/3.htm

http://www.un.org/Depts/dpko/dpko/intro/4.htm

http://www.un.org/Depts/dpko/dpko/intro/5.htm

http://www.un.org/Depts/dpko/dpko/intro/police.htm

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/AUFPPlatypus/2001/15.html