Current Issues in Criminal Justice

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Current Issues in Criminal Justice |

|

Public Attitudes towards Penalties

for Sexting by Minors

Carianne Blyth[*] and Lynne D Roberts[†]

Abstract

Current child pornography laws in Australia extend to cases where minors transmit sexually explicit material of themselves or others via digital communication (‘sexting’). This is the first study examining attitudes of the Australian adult public regarding criminal laws that can apply to sexting by minors. A sample of 285 Australian adults completed an online questionnaire that presented a scenario concerning adolescent sexting. Participants completed measures of perceived responsibility and deservingness of penalty for both the sext sender and recipient who, in some cases, also forwarded the sext. Overall, support for legal penalties for adolescent sexting was low, except in the case of non-consensual distribution of sexts. The results highlight the public’s concern with the non-consensual forwarding of sexts, providing support for calls to distinguish between consensual and non-consensual sexting in legislation and educational and public campaigns.

Keywords: sexting – public opinion – child pornography – Australia

Introduction

‘Sexting’, variously defined but generally relating to the digital exchange of user-generated sexually explicit content, is a relatively new phenomenon that has been enabled by advancements of technological communication (Lenhart 2009). Broad definitions of what constitutes a prosecutable offence under Australian child pornography laws extend to cases in which children under 18 years of age create, distribute or store sexual material relating to themselves or other children as a result of engaging in sexting (Crofts and Lee 2013; Lee et al 2013). While not designed for sexting by minors, there are few provisions available to protect the possibility of children becoming implicated in these laws (Lee et al 2013; Tallon et al 2012). Most Australian criminal laws rely on the standards of reasonable persons to determine whether or not the nature of an image constitutes offensive child pornographic material (for example, Criminal Code Act 1995 (Cth) s 473.4). In the context of sexting, the standards of reasonable persons can only be surmised, as currently no Australian study has assessed adult public attitudes towards criminal penalties for adolescents who engage in sexting (Crofts and Lee 2013; Tallon et al 2012). Understanding public attitudes about how the law should treat sexting by minors is important for informing appropriate policy and law responses. This study aims to gauge adult community attitudes towards sexting by minors in the hope that policymakers can use this information when assessing and/or reforming current laws that penalise this behaviour.

Nature and prevalence of sexting

Sexting is a media-created portmanteau of the words ‘sex’ and ‘texting’, denoting the practice of transmitting or exchanging user-generated sexual material, usually via mobile phone or the internet, but also extending to other forms of digital communication (Mitchell et al 2012). First reported in 2005 by the media, soon the practice of sexting gained more widespread media, as well as scholarly, attention and debate when minors who had engaged in sexting were charged with child pornography offences, both in Australia and internationally (Powell and Henry 2014; Victorian Parliamentary Law Reform Committee 2013). However, what actually constitutes ‘sexting’ is not currently agreed upon within the literature (Powell and Henry 2014); definitions vary in terms of the content of a sext, the medium used to transmit a sext, and the contextual nature of the sext (Lounsbury, Mitchell and Finkelhor 2011). For example, terms regarding content have ranged in vagueness, from ‘sexually suggestive’ (Gordon-Messer et al 2013:2) pictures, videos, and/or text messages, to ‘pictures depicting the genitals or buttocks for both sexes and/or the breast for females’ (Strassberg et al 2013:17). Despite there being no agreed-upon definition of sexting, researchers have sought to understand its prevalence, often in order to gauge the level of risk of legal ramifications for young people associated with sexting (Klettke, Hallford and Mellor 2014).

Estimated prevalence rates of sexting vary due to the differing definitions, sampling strategies and age groups used across studies (Lounsbury et al 2011). The most widely cited prevalence rates of adolescent sexting come from non-peer reviewed studies (for example, Associated Press-MTV 2009), which are plagued with methodological limitations such as definitional issues, using unrepresentative samples, and including adult participants (Lounsbury et al 2011; Ringrose et al 2012). A systematic review of studies using representative or random samples indicates that approximately one in 10 adolescents have sent, and one in six have received, a sext (Klettke et al 2014). Females are more likely than males to send sexts (Klettke et al 2014), while males are more likely than females to receive sexts, as well as to forward them on to others (Strassberg et al 2013), indicating a possible gendered nature of sexting (Ringrose et al 2012). As the prevalence of sexting increases with age (Mitchell et al 2012), studies that include older participants, unrepresentative samples, and/or do not break down sexting by age may have skewed and uninformative results, and thus have little to assert about the possibility of legal consequences for minors who engage in sexting (Lounsbury et al 2011).

Wolak, Finkelhor and Mitchell (2012) analysed the prevalence of sexting in terms of the characteristics that led police in the United States (‘US’) (who can apply child pornography laws to sexting) to handle cases in different ways. Wolak et al (2012) categorised sexting cases as either ‘aggravated’ or ‘experimental’, and distinguished between youth-only sexting and sexting involving adults. Youth-only aggravated sexting went beyond the possession, creation and/or sending of sexts to involve additional malicious or abusive elements: either ‘intent to harm’ (sexual abuse, maliciousness, extortion) or ‘reckless misuse’ (distribution or creation of an image without the consent of the minor pictured). Experimental sexting was consensual and did not involve an apparent intent to harm, or reckless misuse. Police were more likely to arrest in aggravating cases; however, Wolak et al (2012) noted that, overall, US police were reluctant to treat young people caught sexting as offenders. This theme of delineating between aggravated sexting and sexting arising out of adolescent experimentation is prevalent in the literature and in law reform, as a general consensus grows that the distinction is paramount and legal responses should reflect it (Kushner 2014; Powell and Henry 2014).

Emphasising that a distinction exists between aggravated and experimental sexting suggests that the behaviour is more complex than how laws are currently responding to it (Crofts and Lee 2013; Lee et al 2013). Wolak et al (2012) considered that experimental sexting seemed to arise out of ‘typical adolescent impulses to flirt, find romantic partners, experiment with sex, and get attention from peers’ (2012:6), which fits closely with what other researchers have found to be motivating factors for adolescents (see Mitchell et al 2013; Strohmaier, Murphy and DeMatteo 2014). While it has been noted that sexting may be linked with sexually risky behaviour (Klettke et al 2014), previous research based on self-reports (Mitchell et al 2012), as well as findings from Wolak et al (2012), indicate that only around 30 per cent of sexts depicting minors are associated with aggravating features. Aggravated sexting often involves negative consequences for the person pictured in the sext, such as bullying, humiliation, tarnished reputation, and physical and/or verbal intimidation (Kushner 2014; Strohmaier et al 2014). As such, researchers have suggested that treating all types of sexting equally under the law leads to the over-criminalisation of young people, which can also work to limit adolescent sexual agency and ‘silence alternative experiences of the practice’ (Kushner 2014; Lee et al 2013:45). Powell and Henry (2014) recommend that sexual consent should be at the centre of legal responses to sexting in Australia; thus, considering sexting in terms of whether it can be categorised as aggravated or as experimental is necessary to guide how the law can more appropriately respond to minors engaging in it.

Research into public attitudes regarding penalties for youth sexting is limited, but points to general disagreement regarding how the law treats sexting. Strassberg et al (2013) asked adolescents what they thought should be the consequences for sexting (if any), finding that the single most common response was ‘no consequence’ (21 per cent). Tallon et al (2012) found that most school students surveyed agreed that sharing a nude image of another person without their permission was most harmful and warranted criminal action, with 46.9 per cent and 32.1 per cent agreeing that it was ‘very fair’ or ‘fair’ respectively to criminalise this behaviour. Generally, participants believed that the penalty harshness should match the offence seriousness, with non-consensual image exchanges to be dealt with more harshly than consensual exchanges. Participants also believed that sex offender registration is an inappropriate response (Tallon et al 2012). These findings are important in understanding how adolescents conceptualise sexting and its associated consequences. However, teenagers’ views may be different to adults’ views.

Two peer-reviewed studies have investigated adult attitudes concerning sex offender registration as a sanction for engaging in sexting. Comartin, Kernsmith and Kernsmith (2013) found that participant support for registration was most influenced by the age of the offender, with 50 per cent of participants supporting registration for a 22-year-old offender versus 12 per cent for a 15-year-old offender (Comartin et al 2013). Strohmaier et al (2014) found that 36 per cent of participants agreed that minors should be prosecuted for sexting; however, this was dependent upon their own history of sexting, with those who had previously engaged in sexting being less likely than those who had not to endorse prosecution. However, 31 per cent of participants believed that prosecuting minors who sext should be based on certain factors and 32 per cent of participants believed prosecution should not occur. Sharing images without consent, sexting that led to bullying or harassment, and the age difference between sexters were some examples of the factors participants believed should be considered. Together, the results from these two studies indicate that support for charging young people under child pornography laws is generally low. The results from Strohmaier et al (2014) provide further support for distinguishing sexting that involves aggravating factors from other sexting behaviours.

The two studies to date on adult attitudes towards legal penalties for sexting (Comartin et al 2013; Strohmaier et al 2014) were conducted in the US and the results may not directly apply to the Australian context. In Australia, public perceptions of legal responses to sexting by minors need to be seen within the broader context of public opinion on offenders and sentencing (for example, Mackenzie et al 2012) and increasingly punitive laws for sex offending (Harrison 2013). Australians generally express high levels of punitiveness and low levels of confidence in sentencing (Mackenzie et al 2012). Approximately 80 percent of Australians report that sentencing for sex offenders is too lenient (Mackenzie et al 2012; Warner and Davis 2012) with greater support for harsher penalties for child sex offenders than other types of sex offenders (Devilly and Le Grand 2014).

Legal ramifications for sexting by minors

Sexting by minors falls within legal definitions of child pornography in Australia. These laws relate to the possession, production, and sales/distribution of sexual material of a minor (Criminal Code Act 1995 (Cth) s 473.1). The consequences of conviction under a child pornography offence can include imprisonment and placement on sex offender registers (Crofts and Lee 2013). Variations exist across jurisdictions with regard to penalties and definitions of a ‘child’ (see Table 1 below), making it difficult to discern how a case may be dealt with (Crofts and Lee 2013). In addition, few provisions exist to protect minors from becoming implicated in these laws. At the Commonwealth level, permission from the Attorney-General is required before proceedings relating to a minor can take place; however, this still sees a minor being arrested, charged and remanded before approval can be sought (Tallon et al 2012). The unofficial policy of ‘police discretion’ may also provide protection for some minors (Crofts and Lee 2013), but this may result in inconsistent consequences (Tallon et al 2012). These protections may be inadequate to ensure that minors are guarded from prosecution under laws originally designed to protect them (Albury and Crawford 2012).

Considering that sexting is reportedly consensual in an estimated seven of 10 cases (Mitchell et al 2012; Wolak et al 2012), penalising all minors who engage in this behaviour may be considered unreasonable and to cause more harm than what the laws are attempting to regulate (Kushner 2013; Lee et al 2013). Indeed, much of the media and scholarly discussion surrounding sexting by minors, both in Australia and internationally, has centred on the appropriateness of penalising young sexters with child pornography offences, especially when sexting was consensual (Kushner 2013). In the US, where child pornography laws have encapsulated sexting by minors similarly to Australia’s laws, at least 33 states have either enacted laws specifically targeting sexting or introduced resolutions or Bills addressing sexting (Kushner 2013).

|

Table 1: Summary of Australian legislation related to sexting by

minors

|

|||||||||

|

Legislature

|

Legislation

|

Possession

|

Production

|

Sales/Distribution

|

Age of consent

|

Age of child**

|

|||

|

Section

|

Penalty*

|

Section

|

Penalty*

|

Section

|

Penalty*

|

||||

|

Cth

|

Criminal Code Act 1995

|

474.20

|

15

|

474.20

|

15

|

474.19

|

15

|

18

|

18

|

|

NSW

|

91H

|

10

|

91H

|

10

|

91H

|

10

|

16

|

16

|

|

|

Vic

|

70

|

5

|

68

|

10

|

–

|

–

|

16

|

18

|

|

|

Qld

|

Criminal Code Act 1899

|

228D

|

5

|

228B

|

10

|

228C

|

10

|

16

|

16

|

|

WA

|

Criminal Code Act Compilation Act 1913

|

220

|

7

|

320(6), 321(6)

|

4–10

|

219(1)

|

10

|

16

|

16

|

|

SA

|

Criminal Law Consolidation Act 1935

|

63A

|

5–10

|

63(a)

|

10–12

|

63(b)

|

10–12

|

17

|

17

|

|

Tas

|

Criminal Code Act 1924

|

130C

|

21

|

130, 130A

|

21

|

130B

|

21

|

17

|

18

|

|

ACT

|

65

|

7

|

64A

|

12

|

64A

|

12

|

16

|

18

|

|

|

NT

|

Criminal Code Act

|

125B

|

10

|

125B

|

10

|

125B

|

|

16

|

18

|

|

*Maximum years imprisonment

**Definition of age of child in relation to child pornography and child

abuse material offences

|

|||||||||

In particular, six states have either created defences for minors who engage in sexting or reduced the punishment; four states have adopted diversionary or educational responses; three other states are considering alternative legislative responses; and 10 states, as well as Guam, have enacted legislation specifically for sexting by minors (Strohmaier et al 2014). However, as in Australia, the US has no federal legislation specific to sexting and so minors may still be prosecuted under child pornography laws (Strohmaier et al 2014). Although many US states have recognised the inappropriateness of charging minors with serious adult offences, some states have not (Kushner 2013).

In Australia, only the Victorian Government (2013) has taken pre-emptive action to address the issue of minors at risk of prosecution, or those actually prosecuted, under child pornography offences. The Victorian Parliamentary Law Reform Committee’s (VPLRC 2013) Inquiry into Sexting recommended that defences be created for child pornography offences, and that legislation be introduced for specific offences related to non-consensual distribution of sexts. This was based on the fact that almost all submissions to the Inquiry called for the decriminalisation of consensual sexting, as well as the recognition that non-consensually making available, or threatening to make available, a sexually explicit image of a person to third parties causes the most harm, and thus warranted an appropriate legal penalty (VPLRC 2013). The Victorian Government (2013) accepted in principle these recommendations from the Inquiry and, on 21 August 2014, introduced legislation to Parliament to reflect this commitment (Clark 2014). Despite the Victorian Government’s commitment to amend laws to more appropriately deal with the complexities of sexting by minors (Clark 2014), Australia is yet to see legislation introduced that protects minors from being prosecuted under current child pornography laws (Crofts and Lee 2013).

It is clear that sexting involves an array of behaviours that may require more complex and considered legislation than what is currently available in Australia (Crofts and Lee 2013). Sexting by minors can range from consensual exchange of sexts, to non-consensual malicious distribution to third-parties, to the more extreme situation of ‘sexts’ that capture a criminal offence (for instance, sexual assault); however, none of these scenarios captures the intentions of child pornography laws (Crofts and Lee 2013; Wolak et al 2012). Child pornography laws were designed to protect children from exploitation, but broad definitions of what constitutes an offence under these laws capture sexting by minors and, as such, children can be ‘more seriously harmed by the very laws designed to protect them’ (Crofts and Lee 2013:106). To date, no research has examined Australian public attitudes regarding current criminal law that criminalises sexting by minors, and whether or not sexting that involves aggravated features (such as non-consensual distribution) should constitute its own offence. Considering that there is currently a shift towards rethinking, changing, and/or creating new legislation to address the issue of sexting by minors being dealt with by inappropriate laws in Australia, it is both timely and important to understand local community perspectives of these laws and what the consequences of sexting should be (if any). Most jurisdictions’ laws in Australia rely on the ‘standards of the reasonable persons’ in considering whether or not an image of a child is offensive (Crofts and Lee 2013). As public perceptions have the capacity to influence public policy (Wood 2008), identifying these ‘standards’, and what the public deems as acceptable consequences for youth sexting, may contribute to better-informed public policy decisions.

The present study

The aim of the present study is to determine public attitudes towards criminal penalties for minors who engage in sexting and to gauge whether these attitudes change when a non-consensual element is added to a scenario. The study addresses the following research question: Does perceived responsibility and deservingness of penalties differ by sexter (sender/receiver) and type of sexting (aggravated/experimental)?

This study examines perceptions of responsibility and levels of support for criminal sanctions for aggravated and experimental sexting by minors, using scenarios depicting one minor sending a sext to another. To ensure ecological validity of the study, the scenarios were adapted from a case featured in an online media release (Sommer 2011). Specifically, the scenarios feature a 15-year-old female (Sarah) sending two nude pictures of herself (sexts) to her 15-year-old boyfriend (Ben) via mobile phone. The scenarios varied only by whether Ben kept the sexts private (experimental condition) or forwarded them to another student’s mobile phone, with the distribution of the images reaching ‘at least six other students’ (aggravated condition). This scenario was chosen because the case was referred to the police, and the minors involved could be charged under Australian child pornography laws. Additionally, previous studies have found that more females appear in or create sexts (Mitchell et al 2012), more males receive sexts (Strassberg et al 2013), the average age of sending and/or receiving a sext is 15 (Mitchell et al 2012) and, under all Australian legal definitions, an individual aged 15 is considered as a ‘child’.

Using Wolak et al’s (2012) categorisation of sexting cases, the first scenario presents ‘experimental’ sexting, as it does not involve reckless misuse or intent to harm, while the second scenario presents ‘aggravated’ sexting, due to Ben’s reckless misuse of the image. Given previous research suggests that people believe non-consensual distribution of sexts generates more harm than consensual sexting (Tallon et al 2012), and that prosecuting minors should be based on factors like non-consensual distribution (Strohmaier et al 2014), it was hypothesised that:

H1. The receiver of the sexts in the aggravated scenario will be perceived as more responsible and more deserving of penalties than the sender in the aggravated scenario.

H2. The receiver of the sexts in the aggravated scenario will be perceived as more responsible and more deserving of penalties than both sexters in the experimental scenario.

Early educational and public campaigns on sexting, both in Australia and internationally, have been criticised for ‘responsibilising’ girls for sending sexts (Karaian 2013; Powell and Henry 2014; Salter et al 2013). Given this message, it is hypothesised that:

H3. The sender of the sexts in the experimental scenario will be perceived as more deserving of penalties than the receiver.

Method

This study used a mixed counterbalanced design investigating judgments of responsibility and deservingness of penalties for sexting by sexter (sender or receiver; within subjects component) and scenario (experimental or aggravated; between subjects component).

As the language and laws in the scenarios were based on Australian terms and policies, participation was restricted to Australian residents over 18 years of age. Initial seeds (family, friends and peers) were recruited via convenience sampling through Facebook and email invitations, which included a request to forward the survey link on to others to instigate snowball sampling. The survey was also made available to Curtin University undergraduate psychology students to gain course credit.

An online questionnaire was developed using Qualtrics software. Prior to commencing data collection, the study was approved by Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee. After reading an information sheet and consenting to participate, participants were asked single-item demographic questions regarding age, gender, and years of education completed, before being presented with either the ‘aggravated’ scenario or the ‘experimental’ scenario. Participants then responded to a questionnaire including measures of ‘perceived responsibility’ and ‘deservingness of penalty’ of each of the sexting partners. Participants were also asked for further comments, before being directed to a debriefing page, containing links to resources for information regarding sexting and Australian laws.

The ‘perceived responsibility’ scale was adapted from Corrigan et al’s (2003) unidimensional three-item scale that measures fault, control, and responsibility. A fourth item on blame (Lambert and Raichle 2000) was added to improve the internal reliability of .70 reported by Corrigan et al (2003). An example item is: ‘How responsible, do you think, is Ben for his present situation?’ Participants responded to each item on a nine-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 9 (completely) for Ben and Sarah separately. In the present study, the resultant scales were unidimensional, with good item-total reliability (Cronbach’s α=.80 Sarah; Cronbach’s α=.92 Ben).

As a scale specific to penalties for sexting by minors in Australia does not currently exist in the literature, the researchers developed the ‘deservingness of penalty’ scale. Based on examination of possible penalties across jurisdictions in Australia, the scale comprised six penalties that adolescents could receive for engaging in sexting: juvenile detention; registration as a sex offender; youth supervision/probation order; community service; fine; and charge dismissed (no penalty). An example item is ‘To what extent does Sarah deserve to receive juvenile detention?’, with responses ranging from 1 (not at all deserve) to 6 (entirely deserve). The charge dismissed items were reverse scored prior to analysis. In the present study, the resultant scales were unidimensional, with good internal reliability (Cronbach’s α=.77 Sarah; Cronbach’s α=.84 Ben).

The final sample comprised 285 participants, including 81 males and 203 females (one unspecified). Age ranged from 18 to 57 years (M=22.89, SD=6.14) and education ranged from 10 to 23 years (M=14.93, SD=2.09; 14 unspecified). A-priori power analyses indicated a minimum sample size of 152 participants was required to detect a medium effect at α=.05, with power .8. The sample obtained had sufficient power to detect meaningful effects.

Once data collection was completed, the data was downloaded to SPSS version 20 for analysis. Of the 314 cases downloaded, 28 cases with two or more missing data points on a scale, and one case with an underage participant, were deleted. Little’s MCAR test produced a significant result, χ2 (401, N=285)=470.70, p=.009, indicating that data was not missing completely at random. No variables had five per cent or more missing values. Expectation maximisation was used to replace missing data. Mean scale scores were computed, with higher values indicating a higher level of that construct.

Results

Descriptive statistics for the perceived responsibility and deservingness of penalty measures are presented in Table 2. Perceived responsibility was above the midpoint of the scale

(5, possible scale range 1 to 9) for the sender (Sarah) and receiver (Ben) in the aggravated condition, but only for the sender in the experimental condition. Deservingness of penalty was below the midpoint of the scale (3.5, possible scale range 1 to 6) for both the sender and the receiver in aggravated and experimental conditions. Perceived responsibility and deservingness of penalty were moderately positively correlated (.3–.4) for both the sender and the receiver in each condition (Table 3).

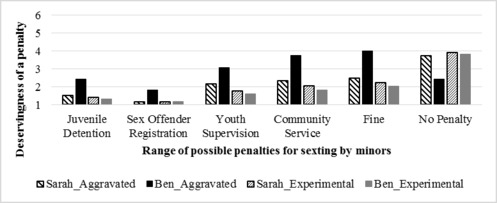

Means of the deservingness of penalty scale items are graphically presented in Figure 1. Of the possible penalties listed, ‘Charge dismissed (no penalty)’ received the strongest support for the sender of the sexts (Sarah) in both conditions and for the receiver of the sexts (Ben) in the experimental condition where the sexts were not forwarded to other students. In descending order, a fine, community service, youth supervision and juvenile detention were supported for the receiver of the sexts (Ben) in the aggravated condition where the sext was forwarded to other students.

Table 2: Descriptive statistics for perceived responsibility and deservingness of penalty for sender and receiver in aggravated and experimental conditions (N=285)

|

|

Receiver

|

|

Sender

|

||

|

|

Aggravated

(N=152)

|

Experimental

(N=133)

|

|

Aggravated

(N=152)

|

Experimental

(N=133)

|

|

|

M (SD)

|

M (SD)

|

|

M (SD)

|

M (SD)

|

|

Perceived responsibility

|

7.64 (1.49)

|

4.87 (2.32)

|

|

6.24 (1.59)

|

6.35 (1.90)

|

|

Deservingness of penalty

|

3.27 (1.19)

|

1.86 (0.83)

|

|

2.16 (.93)

|

1.96 (0.90)

|

|

M=Mean. SD=Standard Deviation.

|

|||||

Table 3: Correlations between perceived responsibility and deservingness of penalty by condition

|

|

Experimental

|

Aggravated

|

|

Sender

|

.364*

|

.382*

|

|

Receiver

|

.309*

|

.408*

|

|

p<.01

|

|

|

Figure 1: Item means for the deservingness of penalty scale

Hypothesis 1, predicting the receiver of the sexts would be perceived as more responsible and more deserving of penalties than the sender in the aggravated scenario, was tested using Wilcoxon signed rank tests due to violations of data normality. Participants in the aggravated condition rated the receiver (Ben) as more responsible than the original sender (Sarah), T=631.50, z=-8.86 (corrected for ties), N–Ties=138, p<.001, two tailed, r=0.75 (‘large’ effect: Cohen 1988). Only 12 participants rated the original sender as more responsible than the receiver (sum of ranks=52.63), whereas 126 rated the receiver as more responsible than the original sender (sum of ranks=71.11), while 14 rated them as the same.

Participants in the aggravated condition rated the receiver (Ben) as more deserving of a penalty than the original sender (Sarah), T=154.50, z=-9.79 (corrected for ties), N–Ties=136, p <.001, two tailed, r=0.84 (‘large’ effect: Cohen 1988). Only six participants rated the original sender as more deserving of a penalty than the receiver (sum of ranks=25.75), whereas 130 rated the receiver as more deserving of penalty than the original sender (sum of ranks=70.47), while 16 rated them as the same. Hypothesis 1 was supported.

Hypothesis 2, predicting the receiver of the sexts in the aggravated scenario would be perceived as more responsible and more deserving of penalties than both sexters in the experimental scenario, was tested using independent samples t-tests. Welch’s t-test was interpreted due to a violation of the assumption of equality of variance. Participants rated the receiver in the aggravated condition as more responsible than the receiver t(283)=11.77, p<.001, 95% CI [2.30, 3.23], two-tailed, d=1.36 (‘large’ effect) and sender t(283)=6.27, p<.001, 95% CI [0.88, 1.68], two-tailed, d=1.24 (‘large’ effect) in the experimental condition. Participants rated the receiver in the aggravated condition more deserving of a penalty than the receiver t(283)=11.73, p<.001, 95% CI [1.18, 1.65], two-tailed, d=1.36 (‘large’ effect) and sender t(284)=10.64, p<.001, 95% CI [1.08, 1.56], two-tailed, d=1.24 (‘large’ effect) in the experimental condition. Hypothesis 2 was supported.

Hypothesis 3, predicting the sender of the sexts will be perceived as more responsible and more deserving of penalties than the receiver in the experimental scenario, was partially supported. Participants in the experimental condition significantly differed on their ratings of sender and receiver on the perceived responsibility (T=6353.50, z=-1.04 (corrected for ties), N–Ties=118, p=.000, two tailed), but not the deservingness of penalty scale, T=1826.50, z=-1.65 (corrected for ties), N–Ties=77, p=.098, two tailed. Only 19 participants rated the receiver as more responsible than the sender (sum of ranks=35.13), whereas 99 rated the sender as more responsible than the receiver (sum of ranks=64.18), while 15 rated them as the same.

Qualitative results

Participants were asked whether they had any further comments on sexting and the law.

Of 285 participants, 105 (35 per cent) made comments. Comments were thematically analysed using the guidelines outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006). The following themes emerged: affect; perceived responsibility (with the subtheme of education); morality of sexting; and deservingness of penalty. To enhance readability, spelling and grammatical errors in quotes have been corrected.

Perceived responsibility

Participants commented on who they thought was responsible for Ben and Sarah’s predicament. This was often related to judgments of the appropriateness of the current laws. Many participants discussed the parents’ responsibility to morally guide and educate their children on the matter: ‘It is a parent’s job to guide and help their child from knowing what’s right from wrong.’ Some participants expressed that both Sarah and Ben were to blame — ‘It is entirely their own fault’— whereas others held just one person responsible: ‘The female is certainly responsible for the photos she voluntarily takes of her body,’ and

‘If the recipient [shares] it, I believe they are then violating the trust given to them and are entirely at fault, not the person who gave them the image in the first instance.’ Many participants who attributed responsibility to the teenager who distributed the image to those outside the pair (Ben in the aggravated scenario) also discussed the need for this person’s punishment: ‘If consent is broken the law should punish the responsible parties.’

Participants frequently discussed the age of Sarah and Ben, and the way in which the current social and technological climate was to blame. Participants discussed how technology and social media may have enabled and/or promoted this type of behaviour:

‘As soon as there were cameras in phones teens were going to send nude pictures of themselves.’ Another expressed, ‘I don’t think you can blame the kids entirely because phones and media are becoming more accessible to them and they aren’t being made 100% aware of the repercussions of using said devices and media in the wrong way.’ Responsibility was excused as a result of the sexters’ ages, with participants attributing their actions to teenagers’ general lack of maturity, foresight, and appreciation of the gravity or long-term ramifications of their actions. These perceptions were mostly linked with comments stating that less strict penalties should exist, or no penalties at all: ‘Unfortunately as a young adolescent you make some stupid decisions ... the older you get the more accountable you should become for your actions but as a young naive juvenile not punished but instead educated on the topic.’

Education

The most recurrent response throughout was related to education. Many participants considered that the matter was ‘not an issue of punishment but education’, attributing Sarah and Ben’s lack of awareness of the laws as the reason for them engaging in sexting: ‘Had there been proper education of the laws surrounding such a case, I’m sure Sarah would have stopped herself from pressing “send” and thus giving permission for public viewing of herself. Also, Ben may have been more vigilant in his actions post receiving the picture.’ Others spoke of the need to educate children on possible non-law-related adverse consequences of sexting, such as the ‘risks of exposure to public criticism if their pictures were to be released, [and] the effects of public humiliation and bullying from peers’.

Morality of sexting

A number of participants expressed moralistic judgments concerning the practice of sexting. Some expressed that sending photographs of oneself to others is ‘unacceptable’, that feeling the need to be sexually explicit is ‘sad’ and that, in general, ‘It’s gross!’ By contrast, others discussed how ‘in the right context sexting is really fun’ and how sexting may be part of development. For instance, ‘learning and exploring with peers is a crucial part of adolescent development, and such a rigid thing as the law struggles greatly when applied to something as organic as childhood development’.

Deservingness of penalty

Participants were divided on their opinions of the current state of the law for underage sexting. Some stated that they did not think ‘child porn offences should ever be used against children themselves. The laws should be used to protect children from adults’, expressing that ‘this is an area that desperately requires reform’. Further, some participants discussed how the law may be intruding on a private matter, with some participants also making reference to the rights of an individual over his or her own body. One participant highlighted the gendered nature of the questionnaire and its potential to influence responses, stating that ‘if the situation was reversed, meaning Sarah forwarded on photographs of Ben, you may find people have a different opinion’.

Many participants discussed the importance of the law in specific circumstances, for instance when the image is distributed non-consensually to others. This was further extrapolated in comments discussing law reform, and it was suggested that ‘special legal codes need to be developed’ and ‘other suitable punishments should be handed out’. Others felt that the current laws were necessary: ‘If the penalties are greater, perhaps children won’t take nude pictures of themselves at all’ and ‘If the law is broken, consequences must be served.’

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to understand public attitudes towards criminal penalties for minors who engage in sexting. The results provide little support for criminalisation of consensual sexting by minors. There was strong support for charges to be dismissed and no penalties to apply for the female sender of the sexts and the male receiver of the sexts who did not forward the sexts on to other students.

Although the receiver/distributor was perceived as the most deserving of penalties, harsher penalties (in particular, sex offender registration and juvenile detention) still received low support across the board. Many participants commented that child pornography laws are simply inappropriate for youth sexting. These findings are consistent with Comartin et al’s (2013) findings of lower support for harsh penalties for sexting by minors than by adults. They are also consistent with Australian experts’ views that current legal responses to sexting are inappropriate and ineffective (Walker, Sanci and Temple-Smith 2013b).

In their ratings of perceived responsibility and deservingness of penalties, survey respondents clearly distinguished between the unauthorised forwarding of sexts in the aggravated condition and consensual experimental sexting. In forwarding sexts on to other students, Ben was rated as higher in perceived responsibility and was seen as more deserving of a penalty than the original sender of the sexts in either condition or the receiver in the experimental condition. The results clearly illustrate the general public’s greater concern with the non-consensual forwarding of sexts than consensual sexting. This provides support for calls to distinguish between consensual and non-consensual sexting in legislation and educational and public campaigns (VPLRC 2013).

In line with campaigns that are viewed as responsibilising girls who send sexts for the behaviour of boys (Karaian 2013; Powell and Henry 2014; Salter et al 2013), responsibility judgments were higher for the female sender of sexts in the aggravated and experimental conditions than for the male receiver who did not forward on the sexts. These findings indicate public perceptions that the act of sending sexts entails responsibility. Potentially this indicates victim blaming; recent research has found that people place responsibility on females for the negative consequences of engaging in sexting, and females experience derogatory labelling and peer disapproval (Ringrose et al 2012; Walker, Sanci and Temple-Smith 2013a). Participant comments holding Sarah responsible provide further support for this speculation. However, the design of this study does not allow an unambiguous interpretation of the higher responsibility judgments for the sender as reflecting the responsibilising of girls. Further research counterbalancing the gender of sender and receiver is required to fully test this hypothesis. The higher responsibility judgments were not reflected in perceived deservingness of penalties, with no significant differences found between sender and receiver in the experimental condition.

Differences in findings between conditions in the present study could be speculated to reflect the level of moral ambiguity between the scenarios. The ‘wrongness’ of experimental sexting by teenagers is debatable, as illustrated by comments from survey respondents that ranged from condemnation to viewing sexting as part of adolescent development. In contrast, the further distribution of sexts to unintended recipients in the aggravated scenario may be deemed unambiguously immoral. The distributor of sexts was deemed most responsible and most deserving of a penalty. Supporting this were comments made by participants that the distributor should be treated more harshly. This is consistent with the greater likelihood of arrest in aggravated than experimental sexting cases, with the distribution of images without consent viewed as ‘involving serious criminal dynamics’ (Wolak et al 2012:7).

A key theme to emerge from the qualitative data was the need for education on sexting and its consequences. This is in line with recommendations from Commonwealth (Joint Select Committee on Cyber-Safety 2011) and state governments (VPLRC 2013) for cyber-safety education and media programs. While both Commonwealth (for example, ThinkUKnow and The Line) and state (for example, NSW’s Safe Sexting — No Such Thing) education campaigns have been conducted in Australia (Walker et al 2013b), early educational campaigns on sexting, both in Australia and internationally, have been criticised for not being informed by teenagers’ experiences and understanding (Walker et al 2013b), and for focusing on responsibilising girls for sending sexts rather than on the behaviours of boys who further distribute the sexts without consent. Responsibilising girls for sending sexts results in the shaming of girls (‘slut shaming’: Karaian 2013) and ‘blaming the victim’ (Powell and Henry 2014) and, as such, early educational campaigns were not recognising societal gendered sexual negotiations (Crofts and Lee 2013; Karaian 2013; Salter et al 2013). Responding to these criticisms, the VPLRC (2013) advocated campaigns targeting non-consensual distributors of sexts, rather than the creators of sexts.

Limitations and future research

The sampling method used and resultant sample is a limitation of the present study. As participants were recruited through a university participant pool and convenience and snowball sampling, the generalisability of findings is limited. Females and the post-secondary educated were overrepresented in the sample. In reviewing studies of attitudes towards sex offenders, Willis, Malinen and Johnston (2013) reported limited evidence for differences in attitudes relating to demographic factors. However, while some recent Australian research on public attitudes towards the sentencing of sex offenders has not found significant differences in attitudes based on demographic characteristics (for example, Devilly and Le Grand 2014), Shackley et al (2014) reported higher levels of education were associated with less negative attitudes towards sex offenders, consistent with previous Australian findings that education is inversely associated with punitiveness (Roberts and Indermaur 2007; Spiranovic et al 2012). The implication for this study is that that the overrepresentation of post-secondary educated participants may have resulted in less punitive responses than would have been achieved if a representative sample of Australians was surveyed. Future research should randomly sample from the general population of Australia to gain a more representative sample.

The current study was based on two scenarios depicting experimental and aggravated sexting. In both scenarios the sender of the sexts was a 15-year-old female and the receiver a 15-year-old male. To further explore the effect of age, gender and sexual orientation on deservingness judgments, it is recommended that further scenarios depict a wider range of ages and vary the gender of sender and receiver of sexts.

Conclusion

This study is the first to assess Australian public attitudes toward youth sexting, and provides strong evidence suggesting the public generally do not support current Australian child pornography laws that extend to cases of experimental sexting by minors. Instead, less punitive ways of dealing with sexting by minors are preferred, including special legal codes for non-consensual distribution and general educational strategies.

References

Albury K and Crawford K (2012) ‘Sexting, Consent and Young People’s Ethics: Beyond Megan’s Story’, Continuum 26, 463–73

Associated Press-MTV (2009) MTV-AP Digital Abuse Study <http://www.athinline.org/MTV-AP_Digital_Abuse_Study_Executive_Summary.pdf>

Braun V and Clarke V (2006) ‘Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology’, Qualitative Research in Psychology 3, 77–101

Clark R (2014) ‘Government to Reform Laws Relating to “Sexting”‘ (August 2014) <http://www.premier.vic.gov.au/images/stories/documents/mediareleases/2014/August/140821_Clark_-_Government_to_reform_laws_relating_to_sexting002.pdf>

Cohen J (1988) Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioural Sciences (2nd ed), Erlbaum

Comartin E, Kernsmith R and Kernsmith P (2013) ‘“Sexting” and Sex Offender Registration: Do Age, Gender, and Sexual Orientation Matter?’, Deviant Behavior 34, 38–52

Corrigan P, Markowitz FE, Watson A, Rowan D and Kubiak MA (2003) ‘An Attribution Model of Public Discrimination Towards Persons with Mental Illness’, Journal of Health and Social Behavior 44, 162–79

Crofts T and Lee M (2013) ‘‘Sexting’, Children and Child Pornography’, Sydney Law Review 35,

85–106

Devilly G and Le Grand J (2014) ‘Sentencing of Sex-Offenders: A Survey Study Investigating Judges’ Sentences and Community Perspectives’, Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, DOI: 10.1080/13218719.2014.931324

Gordon-Messer D, Bauermeister JA, Grodzinski A and Zimmerman M (2013) ‘Sexting among Young Adults’, Journal of Adolescent Health 52, 301–6

Harrison K (2013) ‘An International Comparison of Sentencing Policy and Legislation’ in Harrison K and Rainey B (eds), The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Legal and Ethical Aspects of Sex Offender Treatment and Management, John Wiley & Sons

Joint Select Committee on Cyber-Safety (2011) High-Wire Act: Cyber-Safety and the Young, Commonwealth of Australia

Karaian L (2013) ‘Policing ‘Sexting’: Responsibilization, Respectability and Sexual Subjectivity in Child Protection/Crime Prevention Responses to Teenagers’ Digital Sexual Expression’, Theoretical Criminology 18(3), 282–99

Klettke B, Hallford DJ and Meloor DJ (2014) ‘Sexting Prevalence and Correlates: A Systematic Literature Review’, Clinical Psychology Review 34, 44–53

Kushner A (2013) ‘The Need for Sexting Law Reform: Appropriate Punishment for Teenage Behaviors’, University of Pennsylvania Journal of Law and Social Change 16, 281–303

Lambert AJ and Raichle K (2000) ‘The Role of Political Ideology in Mediating Judgments of Blame in Rape Victims and Their Assailants: A Test of the Just World, Personal Responsibility, and Legitimization Hypotheses’, Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 26, 853–63

Lee M, Crofts T, Salter M, Milivojevic S and McGovern, A (2013) ‘“Let’s Get Sexting”: Risk, Power, Sex and Criminalisation in the Moral Domain’, International Journal for Crime and Justice 2(1),

35–49

Lenhart A (2009) Teens and Sexting: How and Why Minor Teens are Sending Sexually Suggestive Nude or Nearly Nude Images via Text Messaging, Pew Research Centre, <http://www.pewinternet.org/~/media/Files/Reports/2009/PIP_Teens_and_Sexting.pdf>

Lounsbury K, Mitchell KJ and Finkelhor D (2011) The True Prevalence of ‘Sexting’, Crimes against Children Research Centre, University of New Hampshire, <http://www.unh.edu/ccrc/pdf/

Sexting%20Fact%20Sheet%204_29_11.pdf>

Mackenzie G, Spiranovic C, Warner K, Stobbs N, Gelb K, Indermaur D, Roberts L, Broadhurst R and Bouhours T (2012) ‘Sentencing and Public Confidence: Results from a National Australian Survey on Public Opinions Towards Sentencing’, Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology 45, 45–65

Mitchell KJ, Finkelhor D, Jones LM and Wolak J (2012) ‘Prevalence and Characteristics of Youth Sexting: A National Study’, Pediatrics 129, 13–20

Powell A and Henry N (2014) ‘Blurred Lines? Responding to “Sexting” and Gender-based Violence among Young People’, Children Australia 38, 119–24

Ringrose J, Gill R, Livingstone S and Harvey L (2012) A Qualitative Study of Children, Young People and ‘Sexting’. A Report Prepared for the NSPCC <http://www.nspcc.org.uk/globalassets/documents/

research-reports/qualitative-study-children-young-people-sexting-report.pdf>

Roberts LD and Indermaur D (2007) ‘Predicting Punitive Attitudes in Australia’, Psychiatry, Psychology and Law 14, 56–65

Salter M, Crofts T and Lee M (2013) ‘Beyond Criminalization and Responsibilisation: Sexting, Gender and Young People’, Current Issues in Criminal Justice 24, 301–16

Shackley M, Weiner C, Day A and Willis GM (2014) ‘Assessment of Public Attitudes Towards Sex Offenders in an Australian Population’, Psychology, Crime & Law 20, 553–72

Sommer W (2011) ‘Investigation of Child Porn “Sexting” Case among Lee High Students Underway’, Kingston Patch (31 May 2011) Spiranovic CA, Roberts LD and Indermaur D (2012) ‘What Predicts Punitiveness? An Examination of Predictors of Punitive Attitudes Towards Offenders in Australia’, Psychiatry, Psychology and Law 19, 249–61

Strassberg DS, McKinnon RK, Sustaita MA and Rullo J (2013) ‘Sexting by High School Students:

An Exploratory and Descriptive Study’, Archives of Sexual Behavior 42, 15–21

Strohmair H, Murphy M and DeMatteo D (2014) ‘Youth Sexting: Prevalence Rates, Driving Motivations, and the Deterrent Effect of Legal Consequences’, Sexuality Research and Social Policy 11, 245–55

Tallon K, Choi A, Keeley M, Elliott J and Maher D (2012) New Voices/New laws: School-age Young People in New South Wales Speak Out about the Criminal Laws that Apply to their Online Behaviour, National Children’s and Youth Law Centre and Legal Aid NSW <http://www.lawstuff.org.au/__data/

assets/pdf_file/0009/15030/New-Voices-Law-Reform-Report.pdf>

Victorian Parliamentary Law Reform Committee (‘VPLRC’) (2013) Inquiry into Sexting: Report of the Law Reform Committee Inquiry into Sexting, Parl Paper No 230 (2010–2013)

Walker S, Sanci L and Temple-Smith M (2013a) ‘Sexting: Young Women’s and Men’s Views on its Nature and Origins’, Journal of Adolescent Health 52, 697–701

Walker S, Sanci L and Temple-Smith M (2013b) ‘Sexting and Young People: Experts’ Views’, Youth Studies Australia 30, 8–16

Warner K and Davis J (2012) ‘Using Jurors to Explore Public Attitudes to Sentencing’, British Journal of Criminology 52, 93–112

Willis GM, Malinen S and Johnston L (2013) ‘Demographic Differences in Public Attitudes towards Sex Offenders’, Psychiatry, Psychology and Law 20, 230–47

Wolak J, Finkelhor D and Mitchell KJ (2012) ‘How Often are Teens Arrested for Sexting? Data from a National Sample of Police Cases’, Pediatrics 129, 4–12

Wood J (2008) ‘Why Public Opinion of the Criminal Justice System is Important’ in Grannon T (ed), Public Opinion and Criminal Justice, William Publishing, 33–46

[*] BPsych (Hons). Child Protection Worker, Department for Child Protection and Family Support, Cnr Grose and Lake St, Cannington WA 6107, Australia.

[†] PhD. Associate Professor, School of Psychology and Speech Pathology, Curtin University, GPO Box U1987, Perth WA 6845, Australia. Email: lynne.roberts@curtin.edu.au.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/CICrimJust/2014/18.html