Indigenous Law Bulletin

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Indigenous Law Bulletin |

|

Indigenous Gaps in the City

Nicholas Biddle

Every two years the release of the Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage report focuses the nation’s attention on the extraordinary challenge of bringing about substantial convergence in the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous outcomes. The latest report is no different.[1] For example, Indigenous income and home ownership has been increasing and more Indigenous youth are completing Year 12. Good news that should not be overlooked. At the same time though, for many of these indicators, non-Indigenous rates are increasing just as fast or even faster, meaning that the gaps have stayed consistently high. Where there has been substantial convergence (for example in employment levels), the current economic downturn means that recent positive trends may be short-lived.

Much of the policy focus and debate in Indigenous affairs in Australia is concerned with remote communities and the various challenges faced by the population who lives there. For example, the Northern Territory Emergency Response (otherwise known as the Northern Territory Intervention) instigated by the former Howard Government and the announcement of 26 Remote Service Delivery Areas by the current Rudd Government[2] are clearly concerned with bringing about substantial change in the outcomes of the remote Indigenous population.

Across most of the standard indicators, there is little doubt that the outcomes of the remote Indigenous population are worse than those of their regional and urban counterparts.[3] This greater level of need explains to a certain extent the policy focus on the remote Indigenous population. However, as explained in this paper, Indigenous disadvantage does not start and stop at remote Australia. This is especially true when comparisons are made with the urban non-Indigenous population. Furthermore, around three out of every four Indigenous Australians in the last (2006) Census identified their usual place of residence as in a regional or urban area. So, while relative need may be greatest in remote Australia, the majority of houses, jobs and education places that will need to be created to meet the Council of Australian Government’s (‘CoAG’) Closing the Gap targets[4] will have to be based in the rest of the country.

In this paper, I summarise the key points from a number of recent studies I have been involved in that relate to the demographic and socioeconomic outcomes of urban and regional Indigenous Australians.

The Geography and Demography of the Urban and Regional Indigenous Population

Table 1 shows the distribution of the Indigenous and non-Indigenous population by the standard five-category remoteness classification used by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (‘ABS’). The first column of numbers gives the Estimated Resident Population for the Indigenous population, and the second column the percentage of the total Indigenous population in that remoteness area. The third and fourth columns repeat the analysis for the non-Indigenous population, with the final column showing the percentage of that remoteness area that identifies as being Indigenous (the Indigenous share).

Table 1 Geographic Distribution of Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Australians, 2006[5]

|

|

Indigenous population

|

Non-Indigenous population

|

Indigenous share

|

||

|

Remoteness classification

|

Estimate

|

Percent

of total

|

Estimate

|

Percent

of total

|

|

|

Major cities

|

165,804

|

32.1

|

13,996,450

|

69.4

|

1.2

|

|

Inner regional areas

|

110,643

|

21.4

|

3,975,154

|

19.7

|

2.7

|

|

Outer regional areas

|

113,280

|

21.9

|

1,854,026

|

9.2

|

5.8

|

|

Remote Australia

|

47,852

|

9.3

|

267,199

|

1.3

|

15.2

|

|

Very remote Australia

|

79,464

|

15.4

|

88,008

|

0.4

|

47.4

|

|

Total

|

517,043

|

100.0

|

20,180,837

|

100.0

|

2.5

|

There are two important points to note from Table 1. In absolute terms, the Indigenous population is concentrated in urban and regional Australia. Almost a third of the Indigenous population lives in a major city, with a further one-fifth living in both inner regional and outer regional Australia. However, it is when compared to the non-Indigenous population that the relative concentration of the Indigenous population in remote Australia becomes apparent. Only 1.2% of the total population in major cities was identified as being Indigenous, compared to 15.2% for remote Australia and 47.4% for very remote Australia.

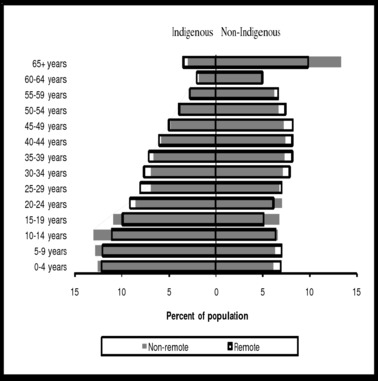

In addition to the geographic differences, there are also substantial demographic differences between the Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations. It is well-known that the Indigenous population is relatively young. However as Figure 1 shows, there are also differences in the age structure between the remote and non-remote populations. In this figure, the percentage of the Indigenous and non-Indigenous population in each five-year age group is graphed, with the solid grey bars indicating the age distribution of the respective non-remote populations (those covered by the first three lines of Table 1), and the clear bars indicating the age distribution of the remote populations (including very remote Australia).

Figure 1 Age Distribution of Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Australians by Remoteness, 2006[6]

While not large, there are some differences between the remote and non-remote Indigenous populations. In particular, there is a greater concentration of non-remote Indigenous Australians of preschool or compulsory school age, but a greater concentration of remote Indigenous Australians in young adulthood and prime working age. Specifically, 49.1% of the non-remote Indigenous population was aged 0–19, compared to 45.1% for the remote Indigenous population. On the other hand, 42.8% of the remote Indigenous population was aged 20–49 years, compared to 39.4% of the non-remote Indigenous population.

Both sets of results highlight a slightly different set of policy priorities in non-remote compared to remote Australia. In non-remote Australia, there is a slight skew towards education provision, whereas in remote Australia there should be a slightly greater emphasis on post-school training and employment opportunities. The greatest impact, however, is likely to be on the trajectory of future population growth.

Indigenous Population Change

Populations are not static and tend to rise or fall through time. If births exceed deaths then populations will tend to grow. However, population movement from migration can also play a significant role in determining population trajectories. In recent times, the Indigenous population has been one of the fastest growing in Australia. The ABS estimates that the Indigenous population grew from 458,500 in 2001 to around 517,000 in 2006. [7] The implied annual growth rate of 2.43% far outstripped that of the general Australian population, a finding that is even more noteworthy when one considers that the Indigenous population is essentially closed, with only minimal impact from international migration.

In a recent study carried out by the Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, John Taylor and I conservatively estimated that, if current levels of fertility and mortality continue, then there will be 848,000 Indigenous Australians by the year 2031.[8] If these trends continue, there will be one million Indigenous Australians by 2040. Importantly from the point of view of this paper, we project the fastest rate of population growth for the urban Indigenous population. In the 10 years from 2006–16 alone, the Indigenous population in Australia’s major cities could grow from around 164,000 to 220,000. This equates to a growth rate of almost 2.97% per annum, far outpacing growth rates for the Indigenous population in inner and outer regional Australia (2.14% and 2.05% respectively), not to mention remote and very remote Australia (0.92% and 0.85% respectively).

There are two main reasons for relatively high projected growth rates in more urban parts of the country. The first is net urban migration. Between 2001 and 2006, 2.2% of the remote Indigenous population moved from remote Australia to major cities, while a further 8.1% moved to inner or outer regional Australia. While there was also a number of Indigenous Australians who moved in the opposite direction, there was still a net transfer from remote to non-remote Australia. Furthermore, the majority of this net transfer was made up of young people, especially those aged 10–24 years. Clearly, if these trends continue, the urban and regional Indigenous population will continue to grow at the expense of the remote population.

The second reason for higher projected growth rates is the greater rate of intermarriage between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians in urban and, to a lesser extent, regional Australia.[9] While children born to Indigenous and non-Indigenous parents continue to be identified as Indigenous themselves, this will lead to a greater number of Indigenous children born than in areas where both parents are Indigenous.

Ultimately, the weight of demography is likely to skew Indigenous affairs policy further and further towards urban and regional Australia.

Indigenous Socioeconomic Outcomes – Results from the 2006 Census

There is clear evidence from the 2006 Census that many of the standard socioeconomic outcomes are worse in remote compared to regional and urban Australia. For example, I developed an index of socioeconomic outcomes that summarised outcomes across employment, education, income and housing in 531 areas in Australia.[10] Although only 31% of the areas were in remote Australia, 83% (110 out of 132) of the areas that were in the bottom quartile — in terms of their socioeconomic outcomes — could be found there.

If the overarching aim of government policy was to reduce the health and socioeconomic disparity within the Indigenous population, then clearly the majority of resources should be devoted to remote Australia. However, the current focus of policy is on closing the gap with the non-Indigenous population. This means that, instead of remote Indigenous Australians, non-Indigenous Australians in the same suburb or town are the most relevant comparison group for non-remote Indigenous Australians. Undertaking such comparisons highlights the major difficulty in meeting the CoAG targets of halving or completely eliminating the discrepancy in life expectancy, employment, education and housing outcomes.[11]

Counter to the view that Indigenous disadvantage starts and stops at remote Australia, I found in another study that there is not a single suburb in Australia’s major cities and large regional towns where the Indigenous population has better or similar socioeconomic outcomes to the non-Indigenous population.[12] In some areas, such as parts of Campbelltown or Blacktown in Sydney, both the Indigenous and non-Indigenous population have poor employment, education, income and housing outcomes. Even then, it is the Indigenous population who has the worst outcomes of all.

Policy Dilemmas and Opportunities

What ties the demographic and socioeconomic results together is that, in order to meet the closing the gap targets, absolute need is likely to be greatest in urban and regional Australia. Specifically, in order to halve the gap in employment outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians, the majority of jobs will need to be found outside of remote Australia and, in particular, in Sydney, Brisbane, Perth and the north coast of New South Wales.[13] The same could also be said for housing and education.[14]

Making substantial inroads into the socioeconomic disparity between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians in urban Australia will present a number of challenges for all levels of government. First, although large in number compared to their remote counterparts, urban Indigenous Australians make up only a small fraction of the city or town in which they live. This makes targeting the employment, education, housing and health services that are required to reduce socioeconomic disparities extremely difficult.

Second, the current slowdown in the economy means that the private sector may be less able to provide the extra jobs needed to close the urban employment gap imagined in February 2008, when the Prime Minister made the historic national Apology to the Stolen Generations and set out the closing the gap commitments; or even in October 2008 when he endorsed Andrew Forrest’s Australian Employment Covenant to secure 50 000 new jobs.[15]

Third, whatever the state of the labour market, Indigenous Australians have to compete with more qualified and experienced non-Indigenous Australians, who do not have a similar personal or family history of dispossession or discrimination. In urban Australia especially, the issue is not whether jobs and schools are available — the greater constraint is the ability of the Indigenous population to take advantage of those opportunities that are available.

Conclusion

The results from the studies summarised in this paper highlight the need for a specific strategy to bring about sustained improvements in socioeconomic outcomes for urban Indigenous Australians. CoAG recognised this need in its recent communiqué, and there is bound to be much interest and scrutiny as its eventual development strategy takes shape. Ultimately, to meet the Closing the Gap targets, all levels of government are going to have to have one eye on remote Australia, with the other firmly placed on Indigenous gaps in the city.

Dr Nicholas Biddle is a Research Fellow at the Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research at the Australian National University. He has completed a PhD in Public Policy, a Masters of Education and a Bachelor of Economics. This paper is an extended version of an opinion piece published in the Sydney Morning Herald on 7 August 2009. I would like to thank Gillian Cosgrove, Jon Altman and John Taylor for comments on previous drafts of the paper.

[1] Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision (‘SCRGSP’), Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage: Key Indicators 2009, (2009).

[2] Jenny Macklin ‘Speech to the John Curtin Institute of Public Policy’, (2009) http://www.jennymacklin.fahcsia.gov.au/internet/jennymacklin.nsf/content/john_curtis_21april09.htm.

[3] Nicholas Biddle, ‘Ranking Regions: Revisiting an Index of Relative Socioeconomic Outcomes’, (2009) 15(2) Australasian Journal of Regional Studies; SCRGSP, above n 1.

[4] Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (‘FaHCSIA’), Closing the Gap on Indigenous Disadvantage: The Challenge for Australia, (2009).

[5] Australian Bureau of Statistics (‘ABS’), Experimental Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, Jun 2006, (2008), cat. no. 3238.0.55.001.

[6] ABS, ibid.

[7] ABS, ibid.

[8] Nicholas Biddle and John Taylor, ‘Indigenous Population Projections, 2006–31: Planning for Growth’, (2009) CAEPR Working Paper No. 56, Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, The Australian National University.

[9] Genevieve Heard, Bob Birrell and Siew-Ean Khoo, ‘Intermarriage between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians’, (2009) 17(1) People and Place.

[10] Nicholas Biddle, above n 3.

[11] FaHCSIA, above n 4.

[12] See Nicholas Biddle, ‘Same Suburb, Different Worlds: Comparing Indigenous and non-Indigenous Outcomes in City suburbs and Large Regional Towns’, (2009) 17(2) People and Place.

[13] Nicholas Biddle, John Taylor and Mandy Yap, ‘Are the Gaps Closing? – Regional Trends and Forecasts of Indigenous Employment’, (2009) 12(3) Australian Journal of Labour Economics.

[14] Nicholas Biddle, ‘The Scale and Composition of Indigenous Housing Need, 2001–06’, (2008) CAEPR Working Paper No. 47, Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, The Australian National University.

[15] AEC (Australian Employment Covenant) About AEC, (2009), available at http://www.fiftythousandjobs.com.au/About-AEC.aspxs

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/IndigLawB/2009/37.html