|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy |

John Muncie

The Open University, UK

|

Abstract

This article focuses on the anomalies and contradictions surrounding the

notion of ‘international juvenile justice’, whether

in its

pessimistic (neoliberal penality and penal severity) or optimistic (universal

children’s rights and rights compliance)

incarnations. It argues for an

analysis which recognises firstly, the uneven, multi-facetted and heterogeneous

nature of the processes

of globalisation; and secondly, how the global, the

international, the national and the local are not mutually exclusive but

continually

interact to re-constitute, re-make and challenge each other.

Keywords

Neoliberal penality, children’s rights, globalisation, racialisation,

criminal responsibility, juvenile justice, comparative

research.

|

The gradual separation of systems of juvenile and youth justice from adult justice that was initiated in many Western jurisdictions from the mid- to the late-nineteenth century onwards normally sought legitimation in a rhetoric of acting in a child’s ‘best interests’. The trajectory that such endeavour has followed, however, has never remained constant, has consistently been prey to over-zealous paternalism, and has characteristically been subjugated to the ‘best interests’ of adults. What may have begun as an attempt to prevent the ‘contamination of young minds’ by separating children and young people from adult offenders in prisons has evolved into a complex of powers and procedures that are both diverse and multi-factorial. Typically, systems of youth justice are beset by the ambiguity, paradox and contradiction of whether children and young people in conflict with the law should be viewed as ‘children first’ and in need of help, guidance and support or as ‘offenders first’ and thereby fully deserving their ‘just desserts’. Traditionally this confusion has played itself out along the axis of ‘welfare’ or ‘justice’. By the 1990s the parameters of such debate were, however, significantly altered by various measures of ‘adultification’ whereby many young people have found that their special protected ‘welfare’ status (as in need of care and separate treatment) has been threatened. Rather, in many western jurisdictions it has become more common for the young to be held fully responsible for the consequences of any transgressive actions. Such developments have, however, been far from universal. At the same time, numerous counter movements have emerged which are designed to further rather than diminish children’s rights. The restorative justice movement, for example, raises the possibility of less formal crime control and more informal offender/victim participation and harm minimisation. The formulation of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1989 stresses the importance of incorporating a rights consciousness into all juvenile justice systems through, for example, the establishment of an age of criminal responsibility relative to developmental capacity; encouraging participation in decision making; providing access to legal representation; protecting children from capital or degrading punishment; and ensuring that arrest, detention and imprisonment are measures of last resort. Above all, the Convention emphasises that the ‘best interests’ of all those aged under 18 should be a primary consideration.

As a result, by the twenty-first century, juvenile justice in many (western) jurisdictions has evolved into a significantly complex state of affairs. Many systems are apparently designed to punish ‘young offenders’ whilst simultaneously, and paradoxically – in keeping with international children’s rights instruments – ensuring that their welfare is safeguarded and promoted as a primary objective. Discourses of child protection, restoration, punishment, public protection, responsibility, justice, rehabilitation, welfare, retribution, diversion, human rights, and so on, intersect and circulate in a perpetually uneasy motion (Muncie and Goldson 2013).

Two quite different global narratives tend to characterise analytical commentaries of international trends in juvenile justice. The first, and most dominant, is essentially dystopian and pessimistic. It conceives a process whereby ‘hegemonic neo-liberalism’ has all but eradicated welfare protectionism and is steadily giving rise to diversifying and intensifying ‘cultures of control’ within which the special status of childhood is diminishing; children’s human rights are systemically violated; and the global population of child prisoners continues to grow. The second, but significantly less developed narrative, is inherently utopian and optimistic. It emphasises the unifying potential of international human rights standards, treaties, rules and conventions and the promise of progressive juvenile justice reform based on ‘best interest’ principles, ‘child friendly’ imperatives and ‘last resort’ rationales.

The concept of the ‘neoliberal’ has become a defining principle of much criminological study of globalisation and comparative criminal/juvenile justice. Neoliberal visions of a globalising world imply (particularly in their ‘strong’ version) that ‘uncontrollable’ economic forces have moved power and authority away from nation states and deposited it in the hands of ‘external’ multinational capital and finance. Shifts in political economy, particularly those associated with international trade and capital mobility, it is argued, have severely constrained the range of political strategies and policy options that individual states can pursue (Bauman 1998; Beck 2006; McGrew and Held 2002). The need to attract international capital has compelled governments to adopt similar economic, social, welfare and criminal justice policies. This has generally involved a drawing back of commitments to social welfare and thereby likely to impact most on juvenile populations (Muncie 2005). Such homogenisation, it is contended, has been facilitated through a fundamental shift in the relations between the state and the market. Unregulated free market economics have become established as sacrosanct ‘natural order’.

For Castells (2008: 82), the institutions of national governance are ill-equipped to deal with such global developments. They are beset by crises of efficiency (major social problems such as global warming, financial collapse and terrorism are beyond nation-state control), legitimacy (collapse in public faith in national politics), identity (state citizenship is subordinated to other community and religious affiliations) and equity (economic competition undermines redistributive welfarism and exacerbates inequalities within and between populations). Significantly the penal realm has expanded to monitor, control and punish increasing numbers in the population who have been rendered ‘out of place’ or ‘undesirable’. Harcourt has argued:

This discourse of neoliberal penality—born in the eighteenth century, nurtured in the nineteenth century, and today in full fruition—facilitates the growth of the carceral sphere. Neoliberal penality makes it easier to resist government intervention in the marketplace and to embrace criminalizing any and all deviations from the market. It facilitates passing new criminal statutes and wielding the penal sanction more liberally because that is where administration is necessary, that is where the state can legitimately act, that is the proper sphere of governing. By marginalizing and pushing punishment to the outskirts of the market, neoliberal penality unleashes the state on the carceral sphere....The logic of neoliberal penality facilitates contemporary punishment practices by encouraging the belief that the legitimate space for government intervention is in the penal sphere—there and there alone. The key to understanding our contemporary punishment practices, then, turns on the emergence in the eighteenth century of the idea of natural order and the eventual metamorphosis of this idea, over the course of the twentieth century, into the concept of market efficiency. (Harcourt 2010: 74-92)

Wacquant (2008, 2009) views such punitiveness not as a consequence but as an integral part of the neoliberal state. His account of the ‘punitive upsurge’ notes six prominent features of the coming together of neoliberalism as a political project and the deployment of a proactive punitive penality. First, punitiveness is legitimated through a discourse of ‘putting an end to leniency’ by not only targeting crime but all manner of disorders and nuisances through a remit of zero tolerance. Second, there has been a proliferation of laws, surveillance strategies and technological quick fixes – from watch groups and partnerships to satellite tracking – that have significantly extended the reach of control agencies. Third, the necessity of this ‘punitive turn’ is everywhere conveyed by an alarmist, catastrophist discourse on ‘insecurity’ and ‘perpetual risk’. Fourth, declining working-class neighbourhoods have become perpetually stigmatised targets for intervention (particularly their ethnic minority, youth and immigrant populations). Fifth, any residual philosophy of ‘rehabilitation’ has been more or less supplanted by a managerialist approach centred on the cost-driven administration of carceral stocks and flows, paving the way for the privatisation of correctional services. Sixth, the implementation of these new punitive policies has invariably resulted in an extension of police powers, a hardening and speeding-up of judicial procedures and, ultimately, increases in the prison population (Wacquant 2008: 10-11). In this regard the epitome of contemporary neoliberal penality is widely assumed to be the United States of America (USA). Indeed Wacquant (2008: 20) has maintained that the USA has been ‘the theoretical and practical motor for the elaboration and planetary [emphasis added] dissemination of a political project that aims to subordinate all human activities to the tutelage of the market’:

The United States has become a major exporter of punitive penal categories, discourses, and policies: with the help of a transnational network of pro-market think tanks, it spread its aggressive gospel of ‘zero-tolerance’ policing, the routine incarceration of low-level drug offenders, mandatory minimum sentences for recidivists, and boot camps for juveniles around the world as part of a neoliberal policy package, fuelling a global firestorm in law and order. (Wacquant 2012: x)

In some contrast, since the 1980s, global human rights provisions with regard to juvenile justice have been formulated via three key instruments.

First, the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Administration of Juvenile Justice (the ‘Beijing Rules’) were adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1985. The Beijing Rules provide guidance for the protection of children’s human rights in the development of separate and specialist juvenile justice systems. and within a comprehensive framework of social justice for all juveniles’ (United Nations General Assembly 1985).

Second, the United Nations Guidelines on the Prevention of Delinquency (the ‘Riyadh Guidelines’) were adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1990. The Guidelines are underpinned by diversionary and non-punitive imperatives: ‘the successful prevention of juvenile delinquency requires efforts on the part of the entire society to ensure the harmonious development of adolescents’ (para. 2); ‘formal agencies of social control should only be utilised as a means of last resort’ (para. 5); and ‘no child or young person should be subjected to harsh or degrading correction or punishment measures at home, in schools or in any other institutions’ (para. 54) (United Nations General Assembly 1990a).

Third, the United Nations Rules for the Protection of Juveniles Deprived of their Liberty (the ‘Havana Rules’) were adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1990. The Havana Rules centre a number of core principles including: deprivation of liberty should be a disposition of ‘last resort’ and used only ‘for the minimum necessary period’ and, in cases where children are deprived of their liberty, the principles, procedures and safeguards provided by international human rights standards, treaties, rules and conventions must be seen to apply’ (United Nations General Assembly 1990b).

These core provisions were bolstered, in 1990, by the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC). The ‘Articles’ of the Convention that have most direct bearing on juvenile justice state that:

• In all actions concerning children ... the best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration (Article 3);

• State Parties should recognise the rights of the child to freedom of association and to freedom of peaceful assembly (Article 15);

• No child shall be subjected to arbitrary or unlawful interference with his or her privacy, family, home or correspondence (Article 16);

• No child shall be subjected to torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment (Article 37a);

• No child shall be deprived of his or her liberty unlawfully or arbitrarily. The arrest, detention or imprisonment of a child shall be in conformity with the law and shall be used only as a measure of last resort and for the shortest appropriate period of time (Article 37b);

• Every child deprived of liberty shall be treated with humanity and respect for the inherent dignity of the human person, and in a manner which takes into account the needs of persons of his or her age; and Every child deprived of liberty shall be separated from adults unless it is considered in the child's best interest not to do so (Article 37c) (United Nations General Assembly 1989).

The United Nations/global human rights instruments have been further buttressed, within the European context, by a movement towards ‘child friendly justice’ that is being driven by the Council of Europe. By extending the human rights principles that inform the ‘European Rules for Juvenile Offenders Subject to Sanctions or Measures’ (Council of Europe 2009), the Committee of Ministers has more recently formally adopted specific ‘Guidelines for Child Friendly Justice’ (Council of Europe 2010). The ‘guidelines’ echo the UNCRC in stating that ‘a “child” means any person under the age of 18 years’ (Council of Europe 2010: Section II (a)) and they apply ‘to all ways in which children are likely to be, for whatever reason and in whatever capacity, brought into contact with ... bodies and services involved in implementing criminal, civil or administrative law’ (Council of Europe 2010: Section I para. 2).

Collectively the United Nations and the Council of Europe human rights standards, treaties, rules, conventions and guidelines provide what is now a well-established ‘unifying framework’ for modelling juvenile justice statute, formulating policy and developing practice in all nation states to which they apply (Goldson and Hughes 2010). As such – at face value at least – it might legitimately be argued that the same instruments provide the basis for ‘globalised’ human rights-compliant and ‘child friendly’ juvenile justice. After all, with the notable exceptions of the USA and Somalia, each of the United Nations member states – 193 ‘States Parties’ in total – have formally ratified the UNCRC and committed themselves to its implementation (Goldson and Muncie 2012). Indeed, the UNCRC is the most ratified of all human rights conventions. Somalia has yet to ratify because, until 2012, it did not have an internationally recognised government. The failure to ratify in the USA is in the main the result of a long campaign by conservative parental rights groups to prevent its consideration. (see, for example, ParentalRights.org) (although one also suspects that there is a general reluctance in the USA to cede any of its authority to the UN).

In many respects, the global narrative of children’s rights is the mirror image of neoliberalism: emphasising state protection rather than individual responsibility; a reduction rather than expansion of the penal sphere; and the promotion of child dignity rather than law and order as core state response. For Tomás, ‘There is now an emergent transnational movement fighting for children’s rights – childhood cosmopolitanism – which constitutes a form of counter-hegemonic globalisation’ (Tomás 2008: 2)

Paradoxically, given their incongruity, both of these ‘global’ narratives are plausible but on their own they are inadequate in grasping the complexities and incoherence of juvenile justice reform. Rather, juvenile justice laws, policies and practices appear formed, applied, and fragmented through a complex of political, socio-economic, cultural, judicial, organisational and local filters. It is also the case that the sovereignty of nation states continues to be vigorously defended and expressed through diverse national domestic law and order agendas.

Rates of imprisonment vary markedly around the world. Using data collected by the International Centre for Prison Studies for 16 industrialised (and what might be broadly considered ‘neoliberal’) nations in 2011/2012, the rate of imprisonment per 100,000 population varied from 730 in the USA to 55 in Japan. Comparing such figures across a 12-year period (from the publication of the first of such lists in 1999) suggests a generalised increase in this rate in most countries but notably in the USA, New Zealand, Scotland, Australia, Greece and England and Wales (Baker and Roberts 2005). Reductions are only notable in South Africa and Germany. But such statistics are arguably most significant in revealing national divergence. For example, they expose the USA imprisoning at a rate 10 times that of Japan and the Scandinavian countries (see Table 1). Such empirical ‘evidence’ seems to contradict any notion of neoliberal homogeneity or of any flattening of national or local political and cultural difference. It suggests that punitiveness (if indeed this can be reliably measured by incarceration rates) cannot simply be reduced to the effect of neoliberal market economies, even though the most advanced neoliberal society (USA) does appear the most punitive. Clearly the effect of neoliberal penality is also mediated by competing penalities and by specific national and cultural characteristics.

The picture is made more complex when we focus solely on custodial rates for under 18 year olds (see Table 2). Data collected through successive surveys carried out for the United Nations Office for Drugs and Crime records a similar diversity in rates of imprisonment, from 0.1 per 100,000 under 18-year-olds in Japan to 73.1 in Scotland. Over the five year period 2005-2010, juvenile prison populations also appear to have remained fairly static with the exception of Greece (26 point increase) and the Netherlands (46 point decrease). It is difficult to observe any generalised international pattern.[1]

Table 1: Comparing prison populations (selected countries)

|

Country

|

Total 2011/12

|

Rate per 100,000 population

|

Increase/ Decrease in rate since 1999

|

|

USA

|

2,266,832

|

730

|

+85

|

|

South Africa

|

157,375

|

310

|

-10

|

|

New Zealand

|

8,433

|

190

|

+45

|

|

England and Wales

|

86,708

|

154

|

+29

|

|

Scotland

|

8,146

|

154

|

+34

|

|

Australia

|

29,106

|

129

|

+34

|

|

Canada

|

39,099

|

117

|

+2

|

|

Greece

|

12,586

|

111

|

+54

|

|

Italy

|

66,009

|

108

|

+23

|

|

France

|

67,373

|

102

|

+12

|

|

Netherlands

|

14,488

|

87

|

+2

|

|

Germany

|

67,671

|

83

|

-7

|

|

Norway

|

3,602

|

73

|

+18

|

|

Sweden

|

6,669

|

70

|

+10

|

|

Finland

|

3,189

|

59

|

+4

|

|

Japan

|

69,876

|

55

|

+15

|

Sources: Derived from International Centre for Prison Studies (2013); Walmsley (1999)

Table 2: Comparing juvenile prison populations (selected countries)

|

Country

|

Total 2009/10

|

Rate per 100,000 under 18s

|

Increase/ Decrease in rate since 2005

|

|

Scotland

|

866

|

73.1

|

- 5.4

|

|

Greece

|

601

|

30.3

|

+ 26.2

|

|

Canada

|

1898

|

27.2

|

- 1.6

|

|

Netherlands

|

696

|

19.6

|

- 46.6

|

|

Australia

|

835

|

16.3

|

+ 3.5

|

|

England and Wales

|

1656

|

13.2

|

- 5.9

|

|

USA

|

9855

|

13.1

|

+ 0.9

|

|

Italy

|

1157

|

11.3

|

+ 2.4

|

|

New Zealand

|

92

|

8.5

|

- 1.4

|

|

Finland

|

73

|

6.7

|

- 1.6

|

|

France

|

669

|

4.9

|

N/A

|

|

Norway

|

6

|

0.8

|

- 0.3

|

|

Sweden

|

8

|

0.7

|

+0.1

|

|

Japan

|

17

|

0.1

|

- 0.2

|

|

Germany

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

|

South Africa

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

Source: Derived from United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2011)

Cavadino and Dignan (2006) have located such patterns in international penality in terms of their relation to differing political economies. They classified these as the ‘neo-liberal’, (such as USA, Australia, South Africa, England and Wales), conservative corporatist (such as Germany, Italy, France and the Netherlands), social democratic corporatist (such as Sweden, Finland) and oriental corporatist (such as Japan). Such typologies clearly suggest that societies which share a broadly similar social and economic organisation will ‘also tend to resemble one another in terms of their penality’ (Cavadino and Dignan 2006: 14). In short, those dependent on the free market and a minimalist welfare state (such as the USA) will have extreme income differentials, a tendency towards social exclusion, and high rates of imprisonment. Other advanced capitalist societies which have preserved a more generous welfare state (such as Norway, Sweden and Finland) will be more egalitarian and inclusionary, leading to relatively lower imprisonment rates (see also Pratt 2008a, 2008b).

There remains a clear danger of falling into a trap of assuming American neoliberal ‘exceptionalism’ is hegemonic and unchallengeable. Even within the USA, whilst overall incarceration rates far exceed those known elsewhere, rates in particular states such as Maine and Minnesota are much closer to a European average than in other states such as Texas and Oklahoma. Similarly the National Conference of State Legislatures (2012) has argued that, in the first decades of the twenty-first century, American penal excess has been tempered (particularly for juveniles) not least by concerns for budgetary restraint and cost effectiveness. They note a state legislative trend to realign fiscal resources from state institutions toward more effective community-based services. This is reflected in an overall decline of juvenile penal populations but even so this movement is not shared by all USA states (see Table 3).

Table 3: Youth confinement in USA states, 1997-2010

|

Increase in confinement rates

|

Decrease in confinement rates

|

||

|

|

|

USA

|

-37%

|

|

Idaho

|

80%

|

Tennessee

|

-66%

|

|

West Virginia

|

60%

|

Connecticut

|

-65%

|

|

Arkansas

|

20%

|

Arizona

|

-57%

|

|

South Dakota

|

8%

|

Louisiana

|

-56%

|

|

Nebraska

|

8%

|

New Jersey

|

-53%

|

|

Pennsylvania

|

7%

|

Georgia

|

-52%

|

Source: Derived from Annie E Casey Foundation (2013)

Local or inter-state differences in rates of juvenile imprisonment are also evident in Australia with incarceration rates varying from 1.55 per 1000 relevant population in the northern territory to 0.12 in Victoria (see Table 4).

Such data suggests that the parameters of global neoliberal penality will always be subject to local translation and/or resistance. Questions also remain of how far a global vision of neoliberal penality resonates beyond the rich industrialised western countries of North America and Western Europe. Criminological research has, like many disciplines, remained blind to experiences outside the countries of the ‘core’. Newburn (2010), for example, maintains that the parameters of neoliberal penality are highly differentiated and will always be shaped and reworked through local cultures, histories and politics. There appears to be discrete and distinctive ways, for example, in which neo-liberal modes of governance find expression in conservative and social democratic rationalities and in authoritarian, retributive, human rights or restorative technologies. The neoliberal penality thesis, then, not only tends to dismiss the continuance and co-existence of competing social democratic forms of penality (Brown 2013) but it also risks imposing a framework shaped by one part of the world onto others to which it does not readily apply, either partially or fully (Lacey 2013).

Table 4: Youth confinement in Australian states, 2012

|

Australian state

|

Number of juveniles in detention

|

Rate per 1000 relevant population

|

|

New South Wales

|

350

|

0.37

|

|

Victoria

|

167

|

0.12

|

|

Queensland

|

153

|

0.32

|

|

Western Australia

|

192

|

0.69

|

|

Northern Territory

|

41

|

1.55

|

|

Australian Capital Territory

|

24

|

0.65

|

|

South Australia

|

76

|

0.41

|

|

Tasmania

|

23

|

0.33

|

Source: Derived from AIHW (2013)

Since the early nineteenth century, most young offender legislation worldwide has been formulated on the basis that young people should be protected from the full weight of the criminal law. It is widely assumed that, under a certain age, young people are doli incapax (literally, incapable of evil) and cannot be held fully responsible for their actions. However the age of criminal responsibility differs widely around the world (Cipriani 2009). In the USA, the minimum set age is six (in North Carolina) but most USA states have set no minimum age at all. This means that some offences committed by under 18-year-olds can attract a mandatory maximum sentence of life imprisonment without parole. In 2012, the Supreme Court ruled this to be a violation of the USA Constitution’s prohibition of ‘cruel and unusual punishment’. The sentence was made optional, rather than mandatory. Even so, it is believed that America remains the only country in the world that is known to sentence children to die in prison without any hope of release (Ratledge 2012). In this context, it is also worth remembering that the death penalty for 16- and 17-year-old offenders in the USA was only abolished in 2005 (Amnesty International 2012).

In some Islamic societies, such as Iran, the age of criminal responsibility is linked to the age of maturity or puberty which, according to Sharia law, is nine years for girls and 15 years for boys (Alliance of Iranian Women 2010-2013). Across the UK, it varies from eight in Scotland (though as from 2010 under-12s cannot be prosecuted in a criminal court) to 10 in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. These ages are the lowest in the EU (see Table 5). It differs even more markedly across Europe where children up to the age of 14, 16 or 18 are deemed to lack full criminal responsibility and, as a result, tend to be dealt with in civil tribunals rather than criminal courts. In England and Wales, whilst the under10-year-olds cannot be found guilty of a criminal offence, for many years the law also presumed that those under 14 years of age were also incapable of criminal intent. To prosecute this age group, the prosecution had to show that offenders were aware that their actions were ‘seriously wrong’ and not merely mischievous. During the mid 1990s, however, the presumption of doli incapax, which had been enshrined in law since the fourteenth century, was abolished on the basis that ‘children aged between 10 and 13 were plainly capable of differentiating between right and wrong’ (Muncie 2009: 239). Such a view was reiterated in 2012 by the Minister then responsible for youth justice who claimed that ‘from the age of 10 children are able to recognise what they are doing is wrong’ (Blunt 2012: para. 7). This was in direct contradiction to United Nations recommendations – first made in 1995 and repeated ever since – that the UK give serious consideration to raising the age of criminal responsibility and thus bring the UK countries in line with much of the rest of Europe. Further doubt on the full responsibility of children (defined as under 18-year-olds by the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child) has been cast by neuroscience research (Royal Society 2011) which has concluded that mature decision making and impulse control is not fully formed until at least 20 years of age. Nevertheless, the possibility of raising the age of criminal responsibility not only in the England and Wales but also Australia seems to be far from heading current political agendas.

Table 5: Variance in ages of criminal responsibility (selected countries)

|

Country

|

Commencement age

|

|

USA

|

6+ (state variance)

|

|

Scotland

|

8 (but no criminal court prosecution before 12)

|

|

Australia

|

10

|

|

England and Wales

|

10 (doli incapax abolished 1998)

|

|

Northern Ireland

|

10 (under review)

|

|

Canada

|

12 (established 1984)

|

|

Ireland

|

12 (raised from 7 in 2001)

|

|

Netherlands

|

12

|

|

Greece

|

12

|

|

France

|

13

|

|

New Zealand

|

14

|

|

Germany

|

14

|

|

Japan

|

14 (lowered from 16 in 2000)

|

|

Italy

|

14

|

|

Spain

|

14 (raised from 12 in 2001)

|

|

Denmark

|

15 (lowered to 14 in 2010)

|

|

Finland

|

15

|

|

Norway

|

15 (raised from 14 in 1990)

|

|

Sweden

|

15

|

|

Belgium

|

18

|

Source: Derived from Muncie (2009)

Continual disputes over the constitution of ‘the child’ and how those ‘in conflict with the law’ might be best treated further reveals not only international diversity but also how the meaning of justice is subject to ongoing revision not only between but also within nation state territories (Muncie 2011a).

An overview of 29 developed countries, drawing on data for 2009/10, indicates that children in the Netherlands enjoy the highest level of wellbeing. The report, published by UNICEF (2013), measures wellbeing on the basis of 26 indicators grouped into five dimensions: material wellbeing; health and safety; education;, behaviours and risks; and housing and environment. Comparison with an earlier analysis of data from 2001/2002 (UNICEF 2007) shows that Finland and the Netherlands ranked in the top three countries for child wellbeing on both occasions; Austria, Greece, Hungary the United Kingdom (UK) and the USA were all placed in the bottom third of the table in both 2001/2002 and 2009/2010. In the more recent period, child wellbeing in Romania, a country not included in the earlier assessment, was ranked lowest (see Table 6).[2]

Table 6: Child well being rankings in 29 ‘rich’ countries, 2010

|

Order

|

Country

|

Child well being ranking

|

|

|

1

|

Netherlands

|

2.4

|

(highest well being)

|

|

2

|

Norway

|

4.6

|

|

|

3

|

Iceland

|

5.0

|

|

|

4

|

Finland

|

5.4

|

|

|

5

|

Sweden

|

6.2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

13

|

France

|

12.8

|

|

|

14

|

Czech Republic

|

15.2

|

|

|

15

|

Portugal

|

15.6

|

|

|

16

|

UK

|

15.8

|

|

|

17

|

Canada

|

16.6

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

25

|

Greece

|

23.4

|

|

|

26

|

USA

|

24.8

|

|

|

27

|

Lithuania

|

25.2

|

|

|

28

|

Latvia

|

26.4

|

|

|

29

|

Romania

|

28.6

|

(lowest well being)

|

Source: Derived from UNICEF (2013)

Formulations of criminal and juvenile justice continue to operate in ways that are specific to local conditions and cultural contexts and reflective of the goals of particular policy makers and agendas. Beckett and Western’s (2001) correlations of welfare benefit and prison populations across the USA found that ‘punitive states’ (such as Texas and Louisiana) had the lowest welfare provision, whilst ‘non-punitive states’ (such as Minnesota and Vermont) had the most generous. Similarly, in 2006, the Crime and Society Foundation published research exploring the relationship between the proportion of gross domestic product (GDP) devoted to welfare expenditure within 18 western countries, and the local rate of imprisonment (Downes and Hansen 2006). The report concluded that ‘welfare aims’ have become increasingly marginalised ‘as key variables in criminal justice policy and practice’ (Downes and Hansen 2006: 3), despite evidence that a generous welfare state might enhance perceptions of fairness, social cohesion and stability. But welfare and imprisonment appear inversely related, producing remarkable diversity rather than convergence. Countries with higher rates of welfare investment are likely to enjoy lower rates of custody, and vice versa. All those countries – including the UK – with the highest rates of imprisonment spend below average proportions of their GDP on welfare; those with the lowest levels of incarceration (such as Finland, Sweden, Denmark and Belgium – but not Japan) have above average welfare expenditure (see Table 7).

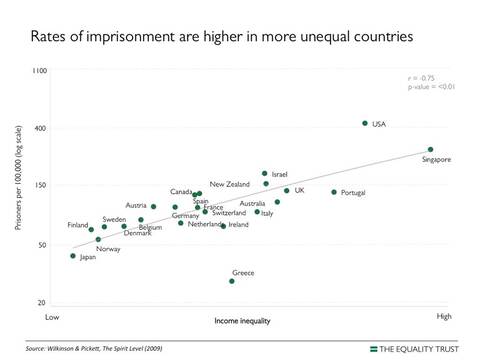

Such diversity has also been explained with reference to income differentials and social inequality. The more stratified a society, the more likely the resort to imprisonment. Wilkinson and Pickett (2007, 2009) suggest that more unequal societies are ‘socially dysfunctional’ in many different ways. It is striking that a group of more egalitarian countries (usually including Japan, Sweden, and Norway) perform well on a variety of outcomes (including resort to imprisonment), whilst more unequal countries (including the USA and the UK) tend to have poorer outcomes (see Figure 1). Tonry (2009) concludes that:

... moderate penal policies and low imprisonment rates are associated with low levels of income inequality, high levels of trust and legitimacy, strong welfare states, professionalised as opposed to politicised criminal justice systems and consensual rather than conflictual political cultures. (Tonry 2009: 381)

Table 7: The relationship between welfare expenditure and prison rates, 1998

|

Country

|

Imprisonment rates per

100,000 population(15+)

|

% of GDP on welfare

|

|

USA

|

666

|

14.6

|

|

Portugal

|

146

|

18.2

|

|

New Zealand

|

144

|

21.0

|

|

UK

|

124

|

20.8

|

|

Canada

|

115

|

18.0

|

|

Spain

|

112

|

19.7

|

|

Australia

|

106

|

17.8

|

|

Germany

|

95

|

26.0

|

|

France

|

92

|

28.8

|

|

Luxembourg

|

92

|

22.1

|

|

Italy

|

86

|

25.1

|

|

Netherlands

|

85

|

24.5

|

|

Switzerland

|

79

|

28.1

|

|

Belgium

|

77

|

24.5

|

|

Denmark

|

63

|

29.8

|

|

Sweden

|

60

|

31.0

|

|

Finland

|

54

|

26.5

|

|

Japan

|

42

|

14.7

|

Source: Downes and Hansen (2006: 5)

Figure 1: The relationship between income inequality and prison rates

Source: The Equality Trust (2013); Wilkinson and Pickett (2009)

There are of course exceptions to this rule. Italy’s relatively low rate of imprisonment is probably due more to the peculiarities of its legal system in delaying outcomes than a sign of any enduring welfare tolerance; for many years the Netherlands managed to combine a ‘culture of tolerance’ and a strong welfare state with rapidly expanding penal populations (see discussion in various chapters of Nelken (2011). This being the case, American ‘exceptionalism’ (particularly in the 1990s) is also only explicable in terms of its own specific cultural history and its particular configuration of Protestant fundamentalism, governmental structure and racialised ordering (Muncie 2011b). More refined analysis suggests then that ‘the best explanations for penal severity or leniency’ will remain ‘parochially national and cultural’ rather than global or economic (Tonry 2001: 518). The specificities of juvenile justice continue to remain embedded in specific geo-political contexts.

In order to monitor the translation of the UNCRC into the realm of law, policy and practice within the national borders of respective States Parties, an international monitoring body has been established. The United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child comprises 18 democratically elected members drawn from the 193 State parties. The Committee has two principal functions: first, to issue ‘General Comments’ in order to elaborate the means by which the provisions and requirements of the UNCRC should be applied within specific subject-domains; second, to periodically investigate the degree to which each State Party is implementing the Convention – and retaining compliance with it – within its corpus of law, policy and practice. On both counts the Committee has identified institutionalised obstructions to the implementation of the UNCRC in general and, more specifically, serious breaches and violations of the human rights of children within particular juvenile justice systems (Goldson and Muncie 2012). The ‘General Comment’ in respect of juvenile justice (United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child 2007) concludes that implementation of the UNCRC is often piecemeal and that the human rights obligations of State Parties frequently appear as little more than afterthoughts:

... many States parties still have a long way to go in achieving full compliance with CRC, e.g. in the areas of procedural rights, the development and implementation of measures for dealing with children in conflict with the law without resorting to judicial proceedings, and the use of deprivation of liberty only as a measure of last resort... The Committee is equally concerned about the lack of information on the measures that States parties have taken to prevent children from coming into conflict with the law. This may be the result of a lack of a comprehensive policy for the field of juvenile justice. This may also explain why many States parties are providing only very limited statistical data on the treatment of children in conflict with the law. (United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child 2007: para.1)

Concerns regarding piecemeal application or, worse still, regression in the implementation of international human rights standards stem – at least in part – from the fact that the UNCRC is ultimately permissive and breach attracts no formal sanction. In this sense, it may be the most ratified of all international human rights instruments but it also appears to be the most violated, particularly with regard to juvenile justice. Moreover, such violations occur within a context of relative impunity. Abramson (2006), for example, whilst presenting an otherwise positive assessment of the practical impact of the UNCRC in ‘transforming the world of children and adolescents’, argues that juvenile justice is essentially peripheralised and/or unduly disregarded, even to the point of being ‘unwanted’.

With regard to the ‘administration of juvenile justice’, the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child has repeatedly reported violations of children’s human rights in both developed and developing societies. The recurring concerns raised by the Committee particularly relate to issues of intolerance, over use of custody, inhumane treatment, denial of freedom of movement and overrepresentation of ethnic minorities (Goldson and Kilkelly 2013; Kilkelly 2008). Indeed, despite having had over 20 years to move towards full implementation, most states appear to have failed to integrate and embed the Convention within their own domestic juvenile justice law, policy and practice.[3] For example, Muncie’s (2008) research found that in Western Europe, Austria, Finland, Ireland, Germany, Portugal, Switzerland and the UK have each been specifically criticised for failing to separate children from adults in custody and/or for facilitating easier movement between adult and juvenile systems owing to diminishing distinctions between the two (as is characteristic of controversial processes of ‘juvenile transfer’ or ‘juvenile waiver’ that allow for the prosecution of children in adult courts in the USA). Similarly, the United Nations Committee report of 2004 (cited in Muncie 2008) on Germany condemned the increasing number of children placed in detention – especially children of foreign origin – including the custodial detention of children with persons up to the age of 25 years. The report on the Netherlands (2004) expressed concern that custody was no longer being used as a last resort whereas, in its report of the same year on France, the Committee expressed concern over legislation and practice that tends to favour repressive over educational measures, increases in the numbers of children in prison and the resulting worsening of conditions. The Committee has long been critical of the low age of criminal responsibility adopted in the three UK jurisdictions and in Australia. For example, in its latest report on the UK (UN Committee on the Rights of the Child 2008), the committee condemned:

• negative public and media images

• discrimination against minorities and asylum seekers

• high levels of incarceration

• proliferation of DNA testing and retention of samples (over 50, 000 samples were taken from under 18 year olds in 2012)

• gross invasions of privacy and age-specific restrictions on freedom of movement, such as the use of Mosquito devices.

The UN Committee’s commentary on Australia from its latest report in 2012 (UN Committee on the Rights of the Child 2012) includes critique of:

• low age of criminal responsibility

• over representation of Indigenous children

• abuses in custody

• mandatory sentencing in WA

• failure to separate children from adults in Queensland.

The persistent recurrence of human rights violations – over time and across space – is compounded by a manifest racialisation of juvenile justice practice. Muncie (2008) reported that, of 18 Western European jurisdictions studied, 15 were explicitly exposed to critique by the United Nations Committee for negatively discriminating against children from minority ethnic communities and migrant children seeking asylum. The overrepresentation of such children is particularly conspicuous at the polar ends of the system – arrest and penal detention. This especially appears to be the case for the Roma and traveller communities in England and Wales, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Northern Ireland, Portugal, Scotland, Spain and Switzerland; for Moroccan and Surinamese children in the Netherlands; and for other North African children in Belgium and Denmark.

Trends across Europe, as elsewhere in the world, appear to indicate that the regulation and governance of ‘urban marginality’ and poverty is being increasingly prised away from the social welfare apparatus and redefined as ‘crime problems’ within burgeoning ‘penal states’ (Wacquant 2009). Moreover, within such shifts, minority ethnic communities and immigrant groups are bearing the brunt of a ‘punitive upsurge’. In particular, eight million Roma – the largest minority ethnic group in the European Union – are widely reported as enduring systematic discrimination, harassment, ghettoisation, forced eviction, expulsion and detention. By collating data drawn from 22 country-specific reports, Gauci (2009: 6) notes: ‘most ... reports identify the Roma ... as being particularly vulnerable to racism and discrimination ... in virtually all areas of life’. Increased ghettoisation of ‘foreigner’ and Roma communities in various European countries, whether as a result of institutional decisions or practical realities such as chronic unemployment, is serving to consolidate structural exclusion and systematic marginalisation: ‘the creation of spatial segregation and socially excluded localities where communities are effectively denied access to basic services such as water and electricity’ (Gauci 2009: 10).

Of course, such phenomena are not restricted to Europe. Cunneen and White (2006) note similar processes of racialised justice in Australia, for example, in particular a persistent over-representation of Indigenous young people held in juvenile justice detention, despite an apparent favouring of diversion and community-based sentences for other offenders. Research conducted for the AIHW (2013) noted that ‘on an average night in the June quarter 2012, Indigenous young people aged 10-17 were 31 times as likely as non-Indigenous young people to be in detention, up from 27 times in the June quarter 2008’.

In the USA, African-American and Hispanic populations are markedly over-penalised (Acoca 1999; Miller 1996). For example, by 2010, black non-Hispanic males were incarcerated at the rate of 3074 inmates per 100,000 USA residents of the same race and gender. White males were incarcerated at the rate of 459 inmates per 100,000 USA residents (US Department of Justice 2011).

Indeed, some of the most punitive elements of juvenile justice worldwide appear to be increasingly reserved for, and applied to, children from minority ethnic and/or immigrant populations.

Twenty years after the formulation of the UNCRC, UNICEF (2009) reported that:

• 2.2 billion children live in the world

• 1 billion live in poverty

• 8.8 million will die before their fifth birthday

• 150 million 5-14 year olds are exploited in child labour

• 10.1 million have no access to primary education

• 9 million are involved in child slavery

• 1.2 million children are trafficked every year. Two thirds of these are girls under the age of 18

• More than 300,000 children are involved in warfare as child soldiers

In 2006, the United Nations Secretary-General’s ‘Study on Violence Against Children’ (Pinheiro 2006) concluded that:

Millions of children, particularly boys, spend substantial periods of their lives under the control and supervision of care authorities or justice systems, and in institutions such as orphanages, children’s homes, care homes, police lock-ups, prisons, juvenile detention facilities and reform schools These children are at risk of violence from staff and officials responsible for their well-being. Corporal punishment in institutions is not explicitly prohibited in a majority of countries. Overcrowding and squalid conditions, societal stigmatization and discrimination, and poorly trained staff heighten the risk of violence. Effective complaints, monitoring and inspection mechanisms, and adequate government regulation and oversight are frequently absent. Not all perpetrators are held accountable, creating a culture of impunity and tolerance of violence against children. (Pinheiro 2006: 16)

The juxtaposition of universal human rights discourse and international recognition of state responsibilities to safeguard children on the one hand, and the pervasive violation of children by the State parties themselves – particularly those in conflict with the law – on the other hand is, to say the least, anomalous (Goldson 2009). Such anomaly echoes Abramson’s (2000) earlier analysis of the implementation of the UNCRC within juvenile justice systems in 141 countries that revealed widespread absence of ‘sympathetic understanding’. He argued that a complete overhaul of juvenile justice is required in many countries where a range of violations are evident including: inadequate or non-existent training of judges, police and prison authorities; no (or limited) access to legal assistance, advocacy and/or representation; delayed trials; disproportionate sentences; insufficient respect for the rule of law; incidence of police brutality; and improper use of the juvenile justice system to address other social problems. Particular concerns centre around penal detention including: failure to develop alternatives to incarceration; overcrowding and poor conditions in custodial facilities; limited prospects of rehabilitation; infrequent contact between child prisoners and their families; lack of separation between child and adult prisoners; inhumane treatment; and, at the extremes, torture (Goldson and Kilkelly 2013).

A focus on ‘local translations’ can also lose sight of both the enduring function of juvenile justice and the extent of international indifference, whatever the jurisdiction or locality. Despite decades of reform, the historical role of juvenile justice to discipline the disadvantaged child has remained undisturbed. As Goldson argued:

Youth justice systems, however they are nuanced, characteristically process the children of the poor. No matter where we may care to look, the universal gaze of youth justice systems is routinely fixed upon children and young people who endure the miseries of poverty and inequality, alongside related forms of disadvantage including poor housing, educational deficits and both mental and physical ill-health. (Goldson 2004: 28)

A persistent, and more serious problem is how human rights might be equally distributed within a world that is profoundly divided and polarised by social and economic inequalities. UNICEF (2010) has revealed that, even in rich nations, identifiable groups of children are unnecessarily ‘left behind’, subjected to poverty, denied access to ‘well-being’ and exposed to inequality. The UN Committee has also recently detected regressive movement in the form of:

• ‘The continuation of the economic and financial crisis is causing drastic social cuts, reduced employment opportunities – especially for young people and women, reduced health services for the most needy, increased dropouts from school and reduced social protection to children and families.

• Climate change is increasingly affecting the lives of millions of children worldwide. Changes in rainfall patterns, greater weather extremes and increasing droughts and floods can have serious health consequences on children, including increases in rates of malnutrition and the wider spread of diseases.

• Discrimination and xenophobia are on the rise.

• Domestic violence and other forms of violence, including State violence, against children and women are on the rise in all regions of the world.

• A growing tendency to lower the age of criminal responsibility and increase penalties for children found guilty, in a misguided effort to reduce increasing public insecurity and, as a result, weakening the realization of children’s rights’ (United Nations General Assembly 2012: paras. 34-38)

Worldwide, more than 1 billion children lack proper nutrition, safe drinking water, decent sanitation, health-care services, shelter and/or education; and every day, 28,000 children die from poverty-related causes (Goldson and Muncie 2006). According to Save the Children UK (2007), children are treated as commodities across all continents in myriad ways including: child trafficking, child prostitution, bonded child labour, child slavery and child soldiers.

It is difficult to conceive of what international justice for juveniles can actually mean in these contexts. Regrettably, too, criminologists have to date remained relatively silent on these global dimensions of child and juvenile harm.

The two rather obvious conclusions are that not only is compliance with rights frameworks piecemeal but also the neoliberal is highly differentiated and works alongside or within pre-existing social democratic forms of penality. This suggests that we need to go beyond global and binary analyses. The precise nature of any juvenile justice system is contingent on a variety of factors – not just global and international, but also national, regional and local layers of governance – such as cultural history; political commitment to expansionism or diversion; media toleration of children and young people; and the extent of autonomy afforded to professional initiative and discretion. These issues will seriously affect any possibility of whether the UK or Australia (or any other jurisdiction) is actually moving toward a fully rights compliant system of juvenile justice.

There is an ongoing theoretical challenge to articulate the dialectic between local and regional spaces of difference (the contingent relations) and national and international contexts (the determining relations) of juvenile justice reform. At an international level, attempts to adhere to rights directives and to satisfy the demands of a ‘punitive upsurge’ conjure up quite different future scenarios. At a local level, devolved powers, Indigenous versioning, ‘re-branding’ and local practice cultures can also be expected to continue to have a profound unsettling effect on all aspects of juvenile justice policy and practice. In many respects, it is clear that the specificities of juvenile justice continue to operate within differing national frames of penality and in ways that are specific to local conditions and cultural contexts, and reflective of the goals of particular policy makers and political agendas. All such complexities once more reveal the limitations of ‘doing comparative research’ through a lens of either divergence and/or convergence. These traditional tools fail to acknowledge the continually shifting and contested terrain of contemporary juvenile justice. Rather, comparative analysis of juvenile justice draws attention to a succession of local encounters of complicity and resistance between and within national systems. Future comparative analysis must surely continue to focus on how the local, the sub-national, the national, the international and the global intersect differentially in particular contexts rather than assuming that any has an a priori determining effect.

Much of the analytical framework adopted in this paper derives from long term and ongoing collaborative research conducted with my colleague, Professor Barry Goldson, University of Liverpool, UK. I am indebted to him for allowing me to present some of this collective work in this current form.

Correspondence: John Muncie, Emeritus Professor of Criminology, Faculty of Social Sciences, The Open University, Milton Keynes, MK7 6AA, UK. Email: j.p.muncie@open.ac.uk.

Abramson B (2000) Juvenile Justice: The ‘Unwanted Child’ of State Responsibilities. An Analysis of the Concluding Observations of the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, in Regard to Juvenile Justice from 1993 to 2000. Brussels: International Network on Juvenile Justice/Defence for Children International.

Abramson B (2006) Juvenile Justice: The Unwanted Child. In Jensen E and Jepsen J (eds) Juvenile Law Violators, Human Rights and the Development of New Juvenile Justice Systems. Oxford: Hart.

Acoca L (1999) Investing in Girls: A 21st Century Strategy. Journal of the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention V1(1): 3-13.

Alliance of Iranian Women (2010-2013) Under the Islamic Rule. Online: Alliance of Iranian Women. Available at http://allianceofiranianwomen.org/ (accessed 16 August 2013).

Amnesty International (2012) Executions of Juveniles Since 1990. Available at http://www.amnesty.org/en/death-penalty/executions-of-child-offenders-since-1990 (accessed 16 August 2013).

Annie E Casey Foundation (2013) Reducing Youth Incarceration in the United States. Available at http://www.aecf.org/KnowledgeCenter/Publications.aspx?pubguid={DFAD838E-1C29-46B4-BE8A-4D8392BC25C9} (accessed 16 August 2013).

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) (2013) Juvenile Detention Population in Australia 2012, Juvenile Justice Series Number 11. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

Baker E and Roberts J (2005) Globalisation and the new punitiveness. In Pratt J, Brown D, Brown M, Hallsworth S and Morrison W (eds) The New Punitiveness. Cullompton: Willan.

Bauman Z (1998) Globalisation: The Human Consequences. Cambridge: Polity.

Beck U (2006) Power in the Global Age. Cambridge: Polity.

Beckett K and Western B (2001) Governing social marginality: Welfare, incarceration and the transformation of state policy. Punishment and Society 3 (1); 43-59.

Blunt C (2012) Speech to Centre for Social Justice launch of report into youth justice system, 16 January. Available at http://www.justice.gov.uk/news/speeches/previous-ministers-speeches/crispin-blunt/centre-for-social-justice-160112 (accessed 27 August 2013).

Brown D (2013) Prison rates, social democracy, neoliberalism and justice reinvestment. in Carrington K, Ball M, O’Brien E and Tauri J (eds) Crime, Justice and Social Democracy. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Castells M (2008) The new public sphere: The global civil society, communication networks and global governance. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 616: 78-93.

Cavadino M and Dignan J (2006) Penal Systems: A Comparative Approach, London: Sage.

Cipriani D (2009) Children’s Rights and the Minimum Age of Criminal Responsibility: A Global Perspective. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Council of Europe (2009) European Rules for Juvenile Offenders Subject to Sanctions or Measures. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.

Council of Europe (2010) Guidelines of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe on Child Friendly Justice (Adopted by the Committee of Ministers on 17 November 2010 at the 1098th meeting of the Ministers' Deputies). Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

Cunneen C and White R (2006) Australia: Containment or Empowerment?. In Muncie J and Goldson B (eds) Comparative Youth Justice. Sage: London.

Downes D and Hansen K (2006) Welfare and Punishment: The Relationship Between Welfare Spending and Imprisonment Briefing No.2. London: Crime and Society Foundation.

Gauci J-P (2009) Racism in Europe. Brussels: European Network Against Racism.

Goldson B (2004) Differential justice? A critical introduction to youth justice policy in UK jurisdictions. In McGhee J, Mellon M and Whyte B (eds) Meeting Needs, Addressing Deeds- Working with Young People Who Offend. Glasgow: NCH Scotland.

Goldson B (2009) Child incarceration: Institutional abuse, the violent state and the politics of impunity. In Scraton P and McCulloch J (eds) The Violence of Incarceration. London: Routledge

Goldson B and Hughes G (2010) sociological criminology and youth justice: Comparative policy analysis and academic intervention. Criminology and Criminal Justice 10(2): 211-230.

Goldson B and Kilkelly U (2013) International human rights standards and child imprisonment: Potentialities and limitations. International Journal of Children’s Rights 21(2): 345-371.

Goldson B and Muncie J (2006) Rethinking youth justice: Comparative analysis, international human rights and research evidence. Youth Justice: An International Journal 6(2): 91-106.

Goldson B and Muncie J (2012) Towards a global ‘child friendly’ juvenile justice? International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice 40 (1): 47-64.

Harcourt B (2010) Neoliberal penality: A brief genealogy. Theoretical Criminology 14: 74-92.

International Centre for Prison Studies (2013) World Prison Brief. Available at http://www.prisonstudies.org/info/worldbrief/ (accessed 26 August 2013).

Kilkelly U (2008) Youth justice and children’s rights: Measuring compliance with international standards. Youth Justice: An International Journal 8(3): 187-192.

Lacey N (2013) Punishment, (neo) liberalism and social democracy. In Simon J and Sparks R (eds) The Sage handbook of Punishment and Society. London: Sage.

McGrew A and Held D (eds) (2002) Governing Global Transformations. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Miller J (1996) Search and Destroy: African-American Males in the Criminal Justice System. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Muncie J (2005) The globalisation of crime control: The case of youth and juvenile justice. Theoretical Criminology 9(1): 35–64.

Muncie J (2008) The punitive turn in juvenile justice: Cultures of control and rights compliance in western Europe and the USA. Youth Justice: An International Journal 8(2): 107-121.

Muncie J (2009) Youth and Crime, 3rd edn. Sage: London.

Muncie J (2011a) Illusions of difference: Comparative youth justice in the devolved UK. British Journal of Criminology 51(1): 40–57.

Muncie J (2011b) On globalisation and exceptionalism. In Nelken D (ed) Comparative Criminal Justice and Globalisation. Farnham: Ashgate.

Muncie J and Goldson B (2013) Youth Justice: In a child’s best interests? In Simon J and Sparks R (eds) The Sage handbook of Punishment and Society. London: Sage.

National Conference of State Legislatures (2012) Trends in Juvenile Justice State Legislation 2001-2011. Available at http://www.ncsl.org/issues-research/justice/juvenile-justice-trends-report.aspx (accessed 16 August 2013).

Nelken D (ed) (2011) Comparative Criminal Justice and Globalisation. Farnham Ashgate.

Newburn T (2010) Diffusion, differentiation and resistance in comparative penality. Criminology and Criminal Justice 10(4): 341-352.

Pinheiro P S (2006) World Report on Violence Against Children. Geneva: United Nations.

Pratt J (2008a) Scandinavian exceptionalism in an era of penal excess – Part I: The nature and roots of Scandinavian exceptionalism. British Journal of Criminology 48 (2): 119-137.

Pratt J (2008b) Scandinavian exceptionalism in an era of penal excess – Part II: Does Scandinavian exceptionalism have a future? British Journal of Criminology 48, (3): 275-292.

Ratledge L (2012) Inhuman Sentencing: Life Imprisonment of Children in the Commonwealth. Online: Child Rights Information Network. Available at http://www.crin.org/violence/search/closeup.asp?infoID=29148 (accessed 16 August 2013).

Royal Society (2011) Brain Waves 4: Neuroscience and the Law. London: Science Policy Centre, Royal Society.

Save the Children UK (2007) The Small Hands of Slavery. London: Save the Children UK.

Tomás C (2009) Childhood and Rights: Reflections on the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. Available at http://www.childhoodstoday.org/download.php?id=19 (accessed 16 August 2013).

Tonry M (2001) Symbol, substance and severity in western penal policies. Punishment and Society 3(4): 517-536.

Tonry M (2009) Explanations of American punishment policies. Punishment and Society 11(3): 377–394.

UNICEF (2007) Child Poverty in Perspective: An Overview of Child Well-being in Rich Countries, Innocenti Report Card 7.Florence: UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre.

UNICEF (2009) The State of the world’s children, Florence, Unicef

UNICEF (2010) The Children Left Behind: A League Table of Inequality in Child Well-Being in the World’s Rich Countries, Innocenti Report Card 9. Florence, UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre.

UNICEF (2013) Child Well Being in Rich Countries: A Comparative Overview, Innocenti Report Card 11. Florence, Unicef, Innocenti Research Centre.

United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child (2007) General Comment No. 10: Children’s Rights in Juvenile Justice, Forty-fourth session, 15 January – 2 February. Geneva: Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights.

United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child (2008) Consideration of Reports Submitted by States Parties Under Article 44 of the Convention: United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, CRC/C/GBR/CO/4. Geneva: Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights.

United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child (2012) Consideration of Reports Submitted by States Parties Under Article 44 of the Convention: Concluding Observations Australia, CRC/C/AUS/CO/4. Geneva: Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights

United Nations General Assembly (1985) United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Administration of Juvenile Justice. New York: United Nations.

United Nations General Assembly (1989) United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. New York: United Nations.

United Nations General Assembly (1990a) United Nations Guidelines for the Prevention of Juvenile Delinquency. New York: United Nations.

United Nations General Assembly (1990b) United Nations Rules for the Protection of Juveniles Deprived of their Liberty. New York: United Nations.

United Nations General Assembly (2012) Report of the Committee on the Rights of the Child. New York: United Nations.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2011) Juveniles held in prisons, penal institutions or correctional institutions, Table CTS 2011. Available at http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/statistics/data.html (accessed 26 August 2013).

US Department of Justice (2011) Prisoners in 2010. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, NCJ 236096

Wacquant L (2008) Ordering insecurity: Social polarisation and the punitive upsurge. Radical Philosophy Review 11(1): 9-27.

Wacquant L (2009) Prisons of Poverty. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Wacquant L (2012) Probing the meta-prison. In Ross JI (ed) The Globalisation of Supermax Prisons. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Walmsley R (1999) World Prison Population List, 1st edn, Research Findings No 88. London: Home Office.

The Equality Trust (2013) The Spirit Level Slides. Available at http://www.equalitytrust.org.uk/resources/spirit-level-slides (accessed 26 August 2013).

Wilkinson RG and Pickett KE (2007) The problems of relative deprivation: Why some societies do better than others. Social Science & Medicine 65(9): 1965-1978.

Wilkinson RG and Pickett KE (2009) The Spirit Level. London: Allen Lane.

[1] All such statistical data should be treated with a certain amount of caution, particularly for juvenile custodial populations. It is clear that different means are used to record juvenile imprisonment. What is classified as penal custody in one country may not be in others though regimes may be similar. The existence of specialised detention centres, training schools, treatment regimes, reception centres, closed care institutions and so on may all hold young people against their will but may not be automatically entered in penal statistics. (for example, whilst the UNODC estimates the numbers of youth in confinement in the USA to be 9800; the Annie E Casey Foundation (2013) places the figure to be closer to 70,000). Not all countries collect the same data on the same age groups and populations. None seem to do so within the same time periods. Some do not collect any data at all (for example, in this sample no data is available for Germany or South Africa).

[2] A lack of data for some indicators means that some countries , including Australia, Japan and New Zealand are not included in the 2013 well being ranking.

[3] The committee’s reports on individual countries can be accessed on http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/crc/

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/IntJlCrimJustSocDem/2013/15.html