|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy |

Sanja Milivojevic

University of New South Wales, Australia

Alyce McGovern

University of New South Wales, Australia

|

Abstract

In this paper we analyse the kidnapping, rape and murder of Jill Meagher to

highlight a range of issues that emerge in relation to

criminalisation, crime

prevention and policing strategies on social media, issues that, in our opinion,

require immediate and thorough

theoretical engagement. An in-depth analysis of

Jill Meagher’s case and its newsworthiness in traditional media is a

challenging

task that is beyond the scope of this paper. Rather, the focus for

this particular paper is on the process of agenda-building, particularly

via

social media, the impact of the social environment, and the capacity of

‘ordinary’ citizens to influence the agenda-defining

process. In

addition, we analyse the depth of the target audience on social media, the

threat of a ‘trial by social media’,

and the place of social media

in the context of pre-crime and surveillance debates. Finally, we call for more

audacious and critical

engagement by criminologists and social scientists in

addressing the challenges posed by new technologies.

Keywords

Jill Meagher; social media; agenda-building; newsworthiness; surveillance,

victimisation.

|

This paper aims to identify and analyse several predominant issues and discourses as they relate to the burgeoning interrelationship between social media, crime and victimisation. We do this by focusing on a recent high profile case study: the disappearance and murder of Melbourne woman Jill Meagher on Saturday 22 September 2012. In analysing this case, we pay particular attention to the role that social media, especially Facebook, played surrounding the events of the case. In doing so, we stress that this paper in no way intends to scrutinise this criminal case. Thus, it is not our intention to comment on law enforcement actions, criminal justice responses or in any way disregard the victim(s) of this crime. Rather, the paper utilises this case to highlight some issues of concern that criminologists need to be aware of and, more importantly, critically engage with when it comes to crime and victimisation in the digital age.

The paper offers three separate yet interrelated starting points for criminological analysis. Firstly, we examine the phenomenon of agenda-building on social networking platforms. Secondly, we present an overview of the issues that emerge from the agenda-building capacities of social media. We argue that, in this content, target audiences and penetration rates on social media, ‘trial by social media’, and suggested policy changes in relation to this criminal case need to be carefully examined given their potential to lead us into the realm of increased surveillance and cyber-‘society of control’ (Deleuze 1992). Finally, in highlighting these issues, we hope to prompt a rethinking of current practices in relation to intersections of crime and social media, and to start mapping alternative and more comprehensive ways of engaging with these challenges that will, no doubt, continue to inhabit our criminological landscape in many years to come. We begin this discussion with a look at the timeline of events surrounding the case that has served as a ‘signal crime’[1] for the city of Melbourne in particular, and the nation more broadly (Innes 2004).

Gillian ‘Jill’ Meagher went missing around 2:00am on Saturday 22 September 2012, after spending the night with work colleagues at bars in Melbourne's northern suburb of Brunswick. When she failed to return home that evening, her husband Tom contacted police. Following her disappearance, the group ‘Help us Find Jill Meagher’ was created on Facebook on Sunday 23 September at 12:30pm, with administrators of the group urging members of the public to come forward with clues about Meagher’s disappearance. The Facebook group sparked an unprecedented level of interest, and within four days the page had accumulated 90,000 followers (Constanza 2012). At 3:00pm on Sunday 23 September police reacted publicly to Meagher’s disappearance, releasing a statement to the media appealing for people to call Crime Stoppers if they had any information about the case. The following day (Monday 24 September) police located Meagher’s handbag in a secluded lane not far from where she was last seen alive. At the time, police raised the possibility that the discovery of the bag might be ‘a smokescreen’ intended to divert the investigation because the bag had not been found during previous searches of the area. The same day police questioned Jill Meagher’s husband Tom, describing the move as a ‘routine’ procedure (Dowsley and Flower 2012).

On the afternoon of Tuesday 25 September, a shop owner in Brunswick came forward with CCTV footage featuring Meagher captured by a fixed camera located inside her store (Dowsley and Flower 2012). Upon releasing the CCTV footage to the public and media the following day, police signalled that a man wearing a blue hoodie seen speaking to Meagher in the footage was a person of interest (Silvester et al. 2012). Police also announced that they were looking into the possibility that Meagher had been abducted, confirming that her husband was not considered a suspect (Silvester et al. 2012). Prompted by the airing of the footage, a number of women came forward on social media and traditional media outlets, claiming to have been approached or assaulted in the area (Bucci and Levy 2012), possibly even by a man fitting the description of the one depicted in the CCTV footage (Flower and Dowsley 2012).

On 27 September, in response ‘to the concerns of the community’ (Moreland Acting Inspector Gary Stokie, cited in Bucci and Levy 2012), police increased their presence in the Brunswick area, arguing it would alleviate people’s fear in the wake of Meagher’s disappearance. At the same time, police encouraged members of the public to ‘take notice of personal safety tips’ when going out (Moreland Acting Inspector Gary Stokie, cited in Bucci and Levy 2012). By 2:30pm that day, police had arrested Adrian Bayley in relation to Meagher’s disappearance. Bayley took police to Meagher’s gravesite and was charged with murder the following day. Between 25 and 27 September, in the wake of Meagher’s disappearance and the charging of Bayley for her murder, a number of hate groups (including ‘Publicly hang Adrian Ernest Bayley’ and ‘Justice Seekers – Jill Meagher’) were created, calling for the death penalty and retribution against the accused. On 5 April 2013, Bayley pled guilty to the rape and murder of Jill Meagher and was sentenced to life imprisonment with a non-parole period of 35 years on 19 June 2013 (Akerman 2013). His appeal to have the sentence reduced was rejected on 26 September 2013 (Russell 2013).

While social scientists broadly have engaged in a ‘sizeable body of research on Facebook’ (Wilson et al. 2012: 203), criminologists have thus far been somewhat absent from such debates (a notable exception is child sex abuse – see Davidson et al. 2011). We argue that Facebook and other social media platforms need to be positioned firmly within the criminologist’s gaze not only because of the wealth of data these platforms provide but also due to their significant popularity across all age groups and their influence on how people interact and communicate with one another (Wilson et al. 2012). This is because social media is now intimately interacting with many of the issues that we as criminologists can and should be engaging with. As we have written elsewhere (Milivojevic 2011; McGovern and Lee 2012), a range of criminological issues are increasingly being linked to the use of social media including online privacy, victimisation and secondary victimisation, and application of social media in criminal justice interventions.

Needless to say then, with any new research realm – in this case, social media – comes potential obstacles in the designing the research. Indeed, how can one research something as fluid and vibrant as the ‘wall’ of a Facebook page, bearing in mind that in any one day Facebook users are sharing upwards of four billion individual pieces of content on the platform (Wilson et al. 2012)? Questions such as where do we start and what do we capture (for example, what Facebook postings should be monitored given the changeable nature of not only content but also discourse in these forums) bear consideration. In embarking on this particular project, we were aware, as Hewson and Laurent (2008) noted, that:

... there is a danger that researchers may be tempted to implement poorly designed studies [when engaging in Internet-mediated research studies. Thus] ... it is crucial for trustworthiness, reliability, and validity that researchers avoid this approach, and take time to properly explore the existing available guidelines, and to pilot procedures as extensively as possible before gathering data. (Hewson and Laurent 2008: 59-60)

In recognising this, however, the conceptualisation and implementation of this study was carried out very much ‘on the run’ in its early stages. We became aware of the case, were instinctually drawn to the potential issues it raised around social and traditional media, and thus began capturing a range of public and media content before we had established a clear sense of what, if anything, would come from our initial interests. As this case moved from being something of general interest to a potentially fruitful research project, the time period within which to develop a fully articulated research strategy was limited. This was specifically because the speed of the unfolding events was dramatic to say the least, as we later elaborate. Thus we remain aware of the potential limitations this brought to the research approach we have taken. It is, therefore, important to acknowledge that this is a pilot project from which important lessons on researching social media in relation to crime and victimisation will be learnt.

Furthermore, we often found ourselves in the ‘mission creep’ (Wall and Williams 2011) situation where our original research objectives (to identify agenda-building potential of Facebook and other social media platforms) were shifted by the richness of the data available online. We simply did not predict the direction in which the case would turn, let alone the implications for this on social media. This resulted in the broadening of our focus to identify the depth of the target audience on social media, the threat of a ‘trial by social media’, and the place of social media in the context of pre-crime and surveillance debates, all of which we go towards addressing within this paper.

Taking all of these factors into account, the methodology that we employed for this pilot research could be described as a virtual ethnography, which allows researchers to immerse themselves in a social setting (in this case, Facebook sites linked to Jill Meagher's disappearance) and understand the practices of the setting and the ‘complex connections between online and offline social spaces’ (Hine 2008: 258). As Wilson et al. (2012: 203) note with regards to social media, ‘[t]his burgeoning new sphere of social behavior is inherently fascinating, but it also provides social scientists with an unprecedented opportunity to observe behavior in a naturalistic setting’. In this case, we wanted to understand what role, if any, the mainstream media and social media had to play in bringing public attention to the Meagher case, and to observe the way in which social media coverage in particular set the agenda for the story in the traditional (‘terrestrial’) media.

As the story first broke in social media circles – on Facebook and Twitter – we naturally began our observations on these platforms. We joined or became ‘fans’ of the largest Facebook groups dedicated to Jill Meagher’s case by ‘liking’ the page and observing the dynamics and topical issues that emerged in these groups. In the early stages of the story, the primary Facebook page of interest was the ‘Help us Find Jill Meagher’ page (later renamed ‘R.I.P. [Rest in Peace] Jill Meagher’), run by Meagher’s family and friends. As the case progressed, other pages emerged, such as the ‘Publicly Hang Adrian Ernest Bayley’ page, purporting to support the case in various ways. As well as monitoring the pages regularly, we took screenshots of content and comments from the walls of these Facebook pages, creating an archive of visual documents that captured the sentiment, narratives and reactions of members these pages. Relevant pages were located via searches on Facebook of key terms, including the names of the victim and alleged (at that time) offender.

It is critical from the ethics perspective to note that all the groups/pages we monitored were public – open for anyone to join – and all content was visible to members and visitors alike; that is, this material was easily viewable by anyone who came across these pages. As researchers, we engaged in observation of the activity on the pages but did not actively participate; we did not post any content or comments on the group walls/pages. These observations extended over a seven-month period, from late September 2012 when Jill Meagher disappeared until after the trial in April 2013. Importantly, our intention was not to capture a true reflection of the virtual culture, place or people – one of the ‘thorny questions’ of virtual ethnography (Wall and Williams 2011), although this may be the focus of future analysis. Rather, our goal was to identify the potential impacts that the dynamics in social media had on the coverage of this case in traditional, terrestrial media outlets. To complete the virtual ethnography, we supplemented the methodology with a (traditional) media analysis of the initial coverage of Jill Meagher’s case in the leading agenda-setting newspapers, including Fairfax’s The Age and News Media’s Herald Sun, both Melbourne-based publications.

At the turn of the new millennium, Garland and Sparks (2000: 189) noted that ‘[c]ontemporary criminology inhabits a rapidly changing world’. Indeed, the 2000s brought with it the sudden expansion of neo-liberal capitalism, increasing the already hasty processes of globalisation and cultural homogeneity of a more interconnected world. One of the most striking transitions experienced by the contemporary social landscape has been the Internet and associated information technologies, which have not only seen an exponential increase in their usage but also in their scope, magnitude and variety (Jewkes and Yar 2010; Milivojevic 2012). The expansion of Web 2.0 – a platform where content and applications are created by users in a participatory and collaborative fashion (Kaplan and Haenleain 2010) – and its by-product, social media – a medium that is designed to support participation, peer-to-peer conversation, collaboration and community (O’Reilly 2004) – have had a profound impact on the ways in which both terrestrial media and society more generally engage with crime and victimisation. Social networking sites, as platforms that enable users to connect with one another by creating personal profiles and permitting other users to view/comment on their profiles, are increasingly being assessed as potentially risky environments, especially for vulnerable users such as youth and particularly in the context of child sexual abuse, sexual offences, cyber-bullying, and even murder (see, for example, Chamberlin 2012; FBI 2012; Livingstone 2008). Yet, although criminology has always ‘sought to be a contemporary, timely, worldly subject’ (Garland and Sparks 2000: 189), the challenges that the rapid development of information technologies bring to contemporary criminology have been somewhat ignored by both research focusing on the Internet-crime nexus and the development of Internet-based criminological research (Wall and Williams 2011).

Much has already been written about the capacity of the media to shape public opinion based on the ways in which the media prioritise some stories and events over others. Similarly, the potential impact of such reporting on public policy has also been subject to much debate (McCombs 1997, 2004; Sayre et al. 2010; Surette 2007). Also known as agenda-setting, this process places journalists in a privileged position whereby they are not only able to ‘sift and select’ news items in a way that preferences some stories over others, but also frame these stories in ways that present such stories with a particular tone or narrative style (Jewkes 2011: 41-42). Media analysts have also written considerably about factors that impact upon and shape crime reporting, making agenda-setting in the traditional media one of the most researched areas in mass communication and political communication studies (Meraz 2009). What has not yet been studied, however, is the way in which social media is impacting on the agenda-setting process, changing the ways in which news values and the construction of news now operate.

An in-depth analysis of Jill Meagher’s case and its newsworthiness in terrestrial media is a challenging task that is beyond the scope of this paper. As indicated earlier, our focus here is on the process of agenda-building, the impact of the social environment and of ‘ordinary’ citizens to agenda-defining process. A burgeoning debate on the role that social media platforms play in the political landscape (whether in relations to events of ‘Arab Spring’, elections in the US or its potential as an anti-corruption tool in developing countries) focus mostly on the positive implications of social media platforms in relation to political and social transition (see, for example, Bertot et al. 2010). In media studies, social media platforms are identified as new and emerging sources that the traditional media refer to when deciding what to cover, sources that can potentially alter the process of agenda-setting in traditional media outlets (Earley 2010). It has been argued that social media has the potential ‘for agenda building, as journalists look to ... third-party ‘general population’ sources in writing their stories ... and public relations practitioners have begun engaging social media content authors with this in mind’ (Lariscy et al. 2009: 314). The process of agenda-building has been investigated in media studies in relation to blogs (Meraz 2009); however, there is no such engagement when it comes to the impact of social networking platforms on agenda-building processes.

Bearing this in mind, it is worth posing the question: does perceived newsworthiness in the online world impact on terrestrial media coverage of crime and victimisation? Put simply, how might social media – in this case Facebook – be affecting the process of creating news and defining public agenda? The Jill Meagher case can serve as a vehicle through which to explore such questions.

As Jewkes (2011) notes, a story’s newsworthiness or value (or why the specific story ‘makes it’ to the traditional or terrestrial media) is directly associated with its news values such as presence of violence and sex, its unpredictability, threshold, risk, simplification, proximity, visual spectacle and/or conservative ideology. In the case of Jill Meagher’s disappearance and murder, there is little doubt that each of these ‘newsworthiness’ boxes could be ticked: there was the highest possible threshold of importance and drama in this case as a young woman was abducted and murdered a few hundred meters from home, after a night out with colleagues. It was a rare, extraordinary event, highly individualised and gendered, random, meaningless and unpredictable. The victim was raped and murdered. The crime was committed by a stranger, an offender ‘at large’, a dangerous criminal prepared to strike indiscriminately (Jewkes 2011: 51). The victim was presented as nothing short of what Nils Christie (1986) would describe as the ‘ideal victim’: young, vulnerable, attacked by a stranger, respectable. As one media commentator noted at the time:

... [s]he wasn’t a crook, she wasn’t one of the players in the gangland wars, and she wasn’t a heroin addict in a dark alley... She was just an ordinary woman enjoying life and doing what thousands of ordinary young women do. My daughter, your daughter, your friends, your wife. That is the shock and the grief here ... She wasn’t a part of a different world, and she was doing what every person –male or female – should be able to do in a civilised society. (Mitchell 2012)

This ‘ideal victim’ status, however, was developed over time, initially on Facebook and Twitter and later in the terrestrial media. The level of social media engagement with this event was described as ‘unprecedented other than [for] natural disasters in Australia. It’s something that people [took to] to with enormous passion...’ (Boschma cited in Lowe 2012). A few hours after Meagher went missing, social media was saturated with ‘self fancying armchair detectives’ who ‘shared their uninformed, moronic theories on what might have happened’ (Ford 2012). The stills and CCTV footage of Meagher’s last known movements were watched by captivated audiences both before and after the arrest of the accused, appealing both to our voyeuristic tendencies as well as reinforcing our sense of horror and powerlessness (Jewkes 2011: 60). As Aas (2010: 152) puts it, ‘[d]eath is no longer a private affair’. Yet, other cases of missing women who also potentially met with foul play have failed to generate the same level of attention both on social media and in the terrestrial media[2].

A virtual ethnography and the analysis of traditional media reports were revealing about the factors that contributed towards the newsworthiness of the Meagher case as well as the agenda-building capacity of social media. A few hours after Meagher’s disappearance, hundreds of commentators on the Facebook page ‘Help us Find Jill Meagher’ contributed regular postings on a range of issues, from repeated requests for prompt police action and speculation about her husband’s involvement in the case, to appeals for more intense news coverage of the case and pleas to the family to call psychics (Ford 2012). On 26 September, four days after Meagher’s disappearance, around 800 comments were recorded on the page’s Wall (Dowsley and Flower 2012). While most comments were posted by ‘well-intended, concerned citizens’, hundreds of trolls[3] also commented on Meagher’s behaviour, scrutinising and blaming her and her husband for her situation:

She was obviously at a bar/club, left there in the early hours of the morning, obviously partially pissed/drunk, and she 'lead someone on' [sic] and the consequences followed her. if she is going to flirt with someone, make sure that you go through with it because someone is obviously pissed off with her ... in my opinion, it’s now old news, she met with foul play as a result of her actions inside the pub/bar OR as I mentioned before ... ask the husband. (Ford 2012)

Such comments were met with a strong reaction in both online and in traditional media (see Ford 2012), enhancing the story’s newsworthiness in traditional media.

The very first report on Meagher’s disappearance was published on an ABC website a day after her disappearance. At the same time, the first report about the case in the highly influential Melbourne media outlet, The Age, appeared on 24 September, with the title ‘Public hunt for missing woman’. The story began with the line, ‘[a] massive social media campaign is in full swing in a bid to help police to find an ABC employee last seeing leaving a Brunswick bar early on Saturday’ (Cooper 2012). The story continued with the statement that:

As police and her husband yesterday appealed for information on her disappearance, social media took hold. On Twitter, dozens of people posted or retweeted links to news stories, including ABC presenters [while t]he words ‘jill’, ‘meagher’, ‘brunswick’ and ‘vanished’ all separately trended in Australia yesterday. (Cooper 2012)

Moreover, the paper reported that ‘[a] Facebook page created to raise awareness last night had more than 3,000 followers’, quoting Meagher’s husband who commented that the public response on social media was 'massive' (Cooper 2012). Another agenda-setting Melbourne newspaper, the Herald Sun, also followed the case, reporting that ‘[t]here has been an outpouring of tributes to Jill Meagher on a Facebook page set up to help find her’, and indicating that the page had more than 67,000 likes (Dowsley and Flower 2012). The Herald Sun routinely replicated many of the comments about and tributes to Meagher posted on the ‘Help us Find Jill Meagher’ Facebook page (Dowsley and Flower 2012).

As the case progressed, the dynamic and sentiment displayed on the social media transferred into terrestrial media reports. On 25 September, The Age noted that ‘[s]everal women have used a Facebook page set up to find missing ABC employee Jill Meagher to outline scares they have had in the Brunswick area this year’ (Cooper et al. 2012). The paper also reported on the fact that more than 30,000 people ‘liked’ the missing person page ‘Help us Find Jill Meagher’ up to that point (Cooper et al. 2012). A Herald Sun article on 28 September 2012 reported that the role of social media in ‘busting crime’ had been investigated, claiming that ‘[e]ven before Victoria Police had officially confirmed an investigation into disappearance of Jill Meagher, a social media campaign was gathering steam’ (Oderberg 2012). The paper remarked on the 33 million Twitter feeds relating to the case, and the 107,000 likes on Jill Meagher's missing persons Facebook page (Oderberg 2012).

The question as to why Jill Meagher’s case rose to the top of both social media and traditional media outlets is not an easy one to answer. As Asur et al. (2011: 1) note, ‘[s]ocial media generates a prodigious wealth of real-time content’ and yet ‘[f]rom all the content that people create and share, only few topics manage to attract enough attention to rise to the top’. Our analysis of Jill Meagher’s murder case suggests that that this case was initially assessed as ‘newsworthy’ on social media, and it was this interest that subsequently directed attention of the traditional media. Based on the growth of Facebook pages dedicated to her disappearance (in terms of the number of ‘likes’ to relevant pages and groups, number of comments by group members, the dynamics of the online conversations and the pressure aimed at the traditional media and police to report/solve the case) and the coverage that such growth triggered in traditional, terrestrial media, it is our proposition that Jill Meagher’s case was initially made a ‘news story’ on Facebook. This was firstly achieved through ‘conversations’ between concerned citizens and trolls on the ‘Help us Find Jill Meagher's Facebook wall and the visual spectacle and graphic imagery of Jill Meagher, initially staged on Facebook and Twitter and subsequently reprinted in terrestrial media.

A second defining moment in keeping the story newsworthy was the release and the distribution of CCTV footage on YouTube and various missing persons Facebook pages, including the ‘Help us Find Jill Meagher’ page. Indeed even police themselves used social and online media to disseminate the footage. As Frances (2009: 10) notes, '[t]he last decade has witnessed an extraordinary expansion in the nature, power and influence of visual images of crime, social crime and crime control'. In the case of Jill Meagher, the story of crime was told via the broadcasting of ‘ominous’ CCTV footage of a ‘helpless’ victim and ‘ruthless’ predator. Millions of people watched the audio-free footage on YouTube and other social media sites, creating what Sayre et al. (2010) call ‘a reverse flow of information’ in which information from social media made its way to traditional/ terrestrial media outlets. We argue that it was after the frenzy on social media that, because of Meagher’s social status as an ABC employee and the overall newsworthiness of the case described earlier in this paper, the terrestrial media caught up with the story. And while ‘there is no clear picture of what causes [some] topics to become extremely popular, nor how some persist in the public eye longer than others’ (Asur et al. 2011: 1), the agenda-building potential of social media and the response that follows in the traditional media is a vastly important issue for criminologists that might be partially answered by the sheer potential of social media’s global reach and its practically unlimited audience.

The development of ‘Web 2.0’ established a new global communication platform in which Internet users are no longer passive consumers but producers of online content (O’Reilly 2004). Importantly, social networking sites ‘have gained tremendous traction recently as popular online hangout spaces for both youth and adults’ (Boyd 2010). Active users spend more than 9.7 billion minutes per day on the site (Wilson et al. 2012), while 2.5 billion pieces of content and more than 500 terabytes of data is uploaded to Facebook every day (Constine 2012). As of 2013, the most popular social networking site – Facebook – had over 945 million monthly active users (Facebook Newsroom 2013) and was the most visited website in the United States for the consecutive third year, surpassing Google, You Tube and Craigslist (Marketing Charts 2012; Wilson et al. 2012). Across Australia, over 82 per cent of respondents in a survey conducted by Wallace (which equates to over 10.7 million Australian adults) identified themselves as members of at least one social networking site (Wallace 2011: 6). As such, Facebook has a clear ascendancy in the Australian market, with the survey’s results revealing that three out of four respondents currently had a Facebook profile (Wallace 2011: 7).

Social media, as a result, has become an emergent source of information in the modern world (Sayre et al. 2010) and is increasingly analysed in the context of crime and victimisation, including policing (Milivojevic 2012). As Aas (2010) notes, global connectivity on social media is unprecedented with anything we have seen before, and police are relying more and more on the public for vital information about ongoing investigations through these mediums (Lee and McGovern 2014). In the case of Jill Meagher, information was sought through the release of electronic and more traditionally formatted missing persons posters, the distribution of CCTV footage via various online forums and traditional news media broadcasts, and the circulation of Facebook, Twitter and YouTube posts. The numbers that indicate potential reach through social media in this case are numbing:

The two versions of the missing persons poster and the CCTV link on the Facebook page were shared a combined 7432 times, meaning that if the average Facebook user had 130 friends, those items had been seen by more than 966,000 Facebook profiles, not including the sharing of status updates and the page itself. (Ainsworth 2012)

Penetration was sought both vertically within local community – that is, among people who might have valuable information – and horizontally throughout the world, as people expressed their concern and grief for the victim. Thus, in an effort to solve the case, law enforcement, family and friends of Jill Meagher turned to social media to spread the word, a move that led to the case being picked up by the traditional media. Importantly, the CCTV footage and its widespread distribution were heralded as pivotal to solving the case (Mangan and Houston 2012). As one commentator noted, CCTV footage was a ‘good example of ‘action-oriented’ information sharing. Victoria Police ... took a calculated risk, but it absolutely broke open the case’ (Boschma cited in Lowe 2012). It was the access to this footage, a forum provided by social media, that was ‘credited for helping to solve the case, due to the number of people that came forward with information after the CCTV footage had been viewed millions of times on social media’ (Berg 2012).

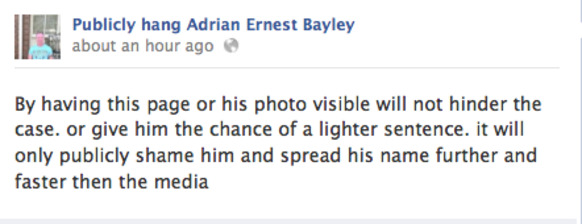

Social media’s role in Jill Meagher’s case did not end with the capture of the alleged offender. On the contrary, it was at this point that the role of Facebook was yet again at the epicenter of public attention. Increased concerns across Australian and international communities, including from law enforcement, regarding the potential negative impacts of social media on ongoing criminal justice investigations and the right to a fair trial were intimately played out in the Meagher case through social media engagement (Lowe 2012). In the 90 minutes after the arrest of Adrian Bayley, ‘social media platforms were ablaze with news of the development and tweets mentioning Ms Meagher’s name hit almost 12 million Twitter timelines, or news feeds, trending across Melbourne and Australia’ (Ainsworth 2012). Meagher’s name was mentioned on Facebook and Twitter every 11 seconds early that morning, while the CCTV footage was watched a further 7,500 times within two hours (Lowe 2012). Social media was initially used to express concern and sympathy, followed by grief and sadness and, finally, anger (Lowe 2012). A few hours after news of the arrest broke, Facebook was swamped by several dozen hate groups and hundreds if not thousands of hateful comments direct towards the accused. One of the largest groups that emerged on Facebook attracted over 7,000 members within a few hours of its creation (Figure 1). A photo of the accused was posted on social media a few hours after his arrest, with words ‘Share this dogs photo ... before the police try to silence us’. The photo was recovered from the accused’s Facebook profile that had been cached on Google (Figure 2). The creator of the hate page argued that ‘[b]y having this page or his photo visible will not hinder the case. Or give him the chance of a lighter sentence. It will only publicly shame him and spread his name further and faster than the media’ (Figure 3). However, similar to McDonald’s (2014: 77) arguments in relation to child sexual abuse, vigilantism and hysteria regarding sex offenders is ‘often misplaced, instilling a false sense of security to the public’. It also triggers questions about the ability of criminal justice system to deliver justice to the victim(s).

Figure 1: Image of ‘R.I.P Jill Meagher’ Facebook page captured within hours of its creation

Figure 2: Photo of Bayley recovered from the accused’s Facebook profile and posted on social media within hours or his arrest

Figure 3: ‘Justification’ for showing the accused’s photo posted by the creator of a Bayley ‘hate page’

On 28 September 2012, the first article about ‘trial by social media’ appeared in the terrestrial media (Lowe 2012). In the article, it was suggested that moderators ‘need to be really careful about what’s put up and they need to start moderating’, and that ‘[t]here’s very, very few who use social media for negative purposes. It’s just that we often tend to talk about the negative purposes’ (Boschma cited in Lowe 2012). Bayley’s defence lawyer applied for the suppression of data about the accused on social media, arguing that ‘it is clear from this material that the accused is the target of intense and almost unprecedented attention, scrutiny, speculation as to his background, and propaganda’ (Russell 2012).

At the same time, Victoria’s Police Chief Commissioner criticised social media, in particular Facebook, for hosting web pages about the accused that incited hatred and undermined the legal system, calling them ‘offensive garbage’ (Dowsley 2012). Victoria Police also used their Facebook page to advise their followers about the consequences of these kinds of breaches. Prison officers were ‘warned not to use social media to vent views about Jill’s death after posts were found on Facebook’ (Finneran 2012b), while Victoria’s Attorney-General warned Facebook that it could face legal action if it failed to remove material that could jeopardise the trial (Cook 2012). After several weeks of refusing to delete hate groups, Facebook finally agreed to take them down (4 October 2012).[4] On 11 October 2012, a web gag on social media was imposed by a magistrate who suppressed the publication of information that could ‘irretrievably compromise the trial’ saying that ‘[t]he mainstream media had not published any material as described in the order sought by the defence, but the area of threat or concern principally lay with ‘non-mainstream media’’ (Anderson 2012).

While the suppression of the accused’s criminal history was implemented in terrestrial media and to some extent enforced on social media in Australia, British and Irish tabloids ran a series of articles on the accused’s violent past and his previous crimes and convictions. They presented assessments from ‘leading criminologists’ that ‘the thug’, ‘deprived beast’, ‘ruthless’, ‘sexual predator’, ‘evil’, ‘the psycho’, ‘the sicko’ Bayley with a ‘gross sexual appetite’ was ‘a ticking time bomb’ and that ‘it was only a matter of time before his actions ended in murder’ (Finneran 2012a). The British tabloid media also reported on death threats the accused murderer was facing in Melbourne prison, stating that ‘[e]ven the crooks are saying they want to kill him because she was innocent’ (Finneran 2012b). Bearing in mind that these articles were easily obtained through a simple Google search, the argument about the suppression of social media content regarding the accused in the light of a fair trial is questionable, to say the least. And while lawyers and social commentators have their say on the topic, especially in the context of parole for sex offenders (c.f. Bartels 2013; Snow 2012), there is a deafening silence from criminologists.[5]

Almost two decades ago Alison Young wrote of the role of technology in presenting images in the murder case of James Bulger, and modern society’s ‘fascination with the visibility of the crime, the victim and the criminals, with visual images provided in abundance by the video cameras and eye-witness reports’ (Young 1996: 112). The fact that such a heinous crime could be committed despite being filmed by security cameras and in front of over 30 witnesses stunned the nation, and the moment when the victim and the offenders disappear from the tape generated the horror that ‘is made to stand in for the horrors of contemporary society’ (Young 1996: 114). Many parallels can be drawn with the case of Jill Meagher. Also similarly, and as with every newsworthy story par excellence, a conservative ideology has been neatly interwoven into Jill Meagher’s case, both in terrestrial and social media. As Jewkes (2011) argues:

Over the last 20 years, Western societies have experienced a rapid growth in the use of surveillance, to the extent where most citizens have come to take for granted that they are observed, monitored, classified and controlled in almost every aspect of their public lives. (Jewkes 2011: 210)

The threat of crime caused/mediated by technology, we have been told, can only be met by more investment in technology and a regulatory state (McGuire 2012). Indeed, cases like Jill Meagher’s further – to borrow again from Haggerty and Ericson (cited in Jewkes 2011: 233) – ‘the general tide of surveillance [that] washes over us all’.

Firmly based in what Furedi (cited in Aas 2010) calls a ‘culture of fear’, in which fear of crime and the pursuit of security shapes criminal justice policies and discourses, the aftermath of Jill Meagher’s case reinforced dangerous stereotypes: that we are all potential victims, that random violence is around us and can erupt at any point, and that dangerous strangers are lurking in public spaces. Rather than focusing on the fact that the accused in this case ‘wasn’t a stranger to women along the busy strip of road from which [Meagher] disappeared’ (Ryan 2012), or indeed on the fact that violence against women is mostly happening within the sacred grounds of a home, there are mounting calls for the expansion of monitoring and surveillance powers within the ‘law and order’ framework. ‘Stranger-danger’ narratives give ‘a (statistically false) impression that the public sphere is unsafe and the private sphere is safe, but also influence government decisions about the prioritization of resources, resulting in the allocation of funding towards very visible preventative measures’ (Jewkes 2011: 53) – in this case CCTV cameras.

In the aftermath of Meagher’s murder, the Premier of Victoria pledged $3 million towards establishing more CCTV cameras to cover the city, while Adelaide City Council introduced more CCTVs, arguing that ‘the power of CCTV was proven in the Jill Meagher murder case in Melbourne, where footage was crucial in the arrest of a suspect’ (Nankervis 2012). Similarly, the then-Federal Opposition Leader at the time promised to spend $50 million over four yours to install CCTV cameras if he won office (ABC News, 8 October 2012). If all of these pledges come to fruition, Australia looks to soon match the UK experience where CCTV technology ‘has been one of the most heavily funded security technologies ... and by the late 1990s represented over three-quarters of total spending on crime prevention’ (McGuire 2012: 92). Yet, as McGuire (2012: 92-3) argues, the returns from these investments have been at best ambiguous, with the London Metropolitan police admitting that approximately only one crime is solved for every 1,000 cameras installed.

Importantly, the ‘surveillant assemblage’ (Haggerty and Ericson 2000) goes beyond calls for more CCTVs in urban areas across Australia. Feeley and Simon’s (1992) concept of actuarial justice, in which the aim of crime policy is to classify and manage populations ranked by risk and develop new surveillance technologies, is arguably climaxing. Prompted by signal crimes that have the potential to change public behaviour and beliefs (Innes 2004) – and there is little doubt that Jill Meagher’s case has become one of these – those assessed as beyond social inclusion, such as convicted murderers, sex offenders and arsonists, are now monitored using GPS tracking systems (Tomazin 2012). Moreover, it is our digital identities – whether we are identified as potential offenders, victims or simply social commentators within our Facebook profiles, Twitter accounts and so on – that are the target point for surveillance, and that can potentially interfere with the administration of justice. As McGuire (2012: 2) notes, ‘technology has begun to acquire an increasing regulatory power of its own – operating as an autonomous force outside the realm of public scrutiny, accountability, or even control’. A myriad of legislation passed in the Global North that expands data retention powers continues to dig up more and more information about our private (digital and terrestrial) lives, for the future use of security services and criminal justice apparatus. When combined with already widespread consumer surveillance, the twenty-first century ‘surveillant assemblage’ leaves little of our private lives (or, in Jill Meagher’s case, even death) private.

As this paper illustrates, crime and victimisation in the context of social media poses a range of important questions for criminologists, some of which have been explored here.[6] However, criminology, unlike many other disciplines in social sciences, continues to underestimate the importance of both researching social media platforms and using them as a research tool. As Garland and Sparks note (2000: 201), in this time of rapid social change, criminology and criminologists have some strategic choices to make: whether to go down the path of ‘specialist underlabourer, a technical specialist to wider debates, providing data and information for more lofty and wide-ranging debates’, or to ‘embrace the world in which crime so loudly resonates ... and [provide] a more critical, more public, more wide-ranging role’. We agree with Earley (2010: 5) in that ‘[a]t the current pace of technological change, it might be unreasonable to expect scholars to hone in on new models. There are just too many parts moving too quickly... Technology will always outpace academic research’. However, we believe that criminologists should be bold enough to engage with the challenges that new information technologies and especially social media bring to the criminological inquiry and, more importantly, to lead the way in understanding the processes and debunking some of the myths that have been plaguing our media, political and social space for some time now.

As the Jill Meagher case has demonstrated, social media’s capacity for agenda-building and its ability to stir the attention of both the traditional media and policy makers is an exceptionally under researched area that requires careful and rigorous criminological investigation. We need to investigate ‘the power [of new media] to push stories into old media’ (Last, cited in Sayre et al. 2010), or what is known as inter-media agenda-setting effect (Golan 2006). More specifically, we need to look at how ‘online victim status’ impacts on the terrestrial media’s perceptions of what is newsworthy and, ultimately, on the associated issues around policy engagement with crime and victimisation in the digital age.

Moreover, we need to engage with the potential impact of social media on criminal justice interventions, both in terms of its usage in policing (see for example Lee and McGovern 2014) and its potential implications on the right to a fair trial. As Taslitz (2011: 1317, original emphasis) argues, ‘there is always a “substantial risk” to a fair trial in media communications in a high-profile case’. If this is the situation – and if, in this global age, one can find information regardless of censorship attempts – are we over-governing social media by limiting privacy and freedom of speech of the public? Indeed, it seems that Castells’ (2001, cited in Aas 2010) notion of the imminent ‘end of privacy’ expressed at the beginning of the noughties is becoming a reality. The long arm of new technologies is getting longer; so too is the intent to police and govern our digital and public lives, with the pursuit of security as its justification. This ‘dataveillance’ (Clarke cited in Aas 2010) and data retention needs to be scrutinised though rigorous and independent criminological inquiry. Jill Meagher’s case suggests that the danger is not necessarily lurking only in the dark shadows of our cities; other dangerous grounds have the potential to further transform our society towards pre-crime and an ultimate Panopticon, in which we will seek to both create human conformity and probe even further into the privacy of those assessed as ‘risky’.

Correspondence: Dr Sanja Milivojevic, School of Social Sciences, University of New South Wales, Kensington Campus, Sydney, 2052, Australia. Email: s.milivojevic@unsw.edu.au

Please cite this article as:

Milivojevic S and McGovern A (2014) The death of Jill Meagher: Crime and punishment on social media. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 3(3): 22-39. doi: 10.5204/ijcjsd.v3i2.144

Aas K (2010) Globalization and Crime. London, Thousand Oaks, New Delhi, Singapore: Sage.

ABC News (2012) Coalition promises $50 million for security cameras, 8 October. Available at http://www.abc.net.au/news/2012-10-08/coalition-promises-2450m-for-security-cameras/4300642 (accessed 4 September 2014).

Ainsworth M (2012) Worldwide reaction to arrest over Jill Meagher’s disappearance on social media. Herald Sun, 28 September.

Akerman P (2013) Jill Meagher's killer Adrian Bayley jailed for life with 35 years non parole. The Australian, 19 June. Available at http://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/nation/jill-meaghers-killer-adrian-bayley-jailed-for-life-with-35-years-non-parole/story-e6frg6nf-1226666134662 (accessed 24 February 2014).

Anderson P (2012) Web gag on hateful Adrian Bayley material in Jill Meagher murder case. Herald Sun, 11 October. Available at http://www.heraldsun.com.au/news/web-gag-on-hateful-adrian-bayley-material-in-jill-meagher-murder-case/story-e6frf7jo-1226493805409?nk=a896e4ab94beebc82829166f0f28625a (accessed 25 February 2014).

Asur S, Huberman B, Szabo G and Wang C (2011) Trends in Social Media: Persistence and Decay. Available at http://arxiv.org/pdf/1102.1402.pdf (accessed 25 February 2014).

Bartels L (2013) Parole and parole authorities in Australia: A system in crisis? Criminal Law Journal 37: 357-376.

Berg A (2012) Social media and Jill Meagher case. Marketing Easy, 1 October. Available at http://marketingeasy.net/social-media-and-the-jill-meagher-case/2012-10-01/ (accessed 25 February 2014).

Bertot J, Jaeger P and Grimes J (2010) Using ICTs to create a culture of transparency: e-government and social media as openness and anti-corruption tools for societies. Government Information Quarterly 27: 264-271

Bishop J (2014) Representations of ‘trolls’ in mass media communication: A review of media-texts and moral panics relating to ‘internet trolling’. International Journal of Web Based Communities 10(1): 7–24.

Boyd D (2010) Social networking sites as networked publics: Affordances, dynamics, and implications. In Papacharissi Z (ed.) Networked Self: Identity, Community, and Culture on Social Networking Sites: 39-58. New York: Routledge.

Brice R (2013) Social media ‘investigators’ tainting court evidence. ABC News, 23 January. Available at http://www.abc.net.au/news/2013-01-23/social-media-use-tainting-court-evidence/4481112 (accessed 5 September 2014).

Bucci N and Levy M (2012) ‘Nothing strange’ about mystery man in Jill footage. The Age, 27 SeptemberAvailable at http://www.theage.com.au/victoria/nothing-strange-about-mystery-man-in-jill-footage-20120927-26m8r.html (accessed 25 February 2014).

Chamberlin T (2012) Links between social media and crime surge as Facebook referenced in thousands of offences logged by police. The Courier Mail, 4 October. Available at http://www.heraldsun.com.au/news/national/links-between-social-media-and-crime-surge-as-facebook-referenced-in-thousands-of-offences-logged-by-police/story-fndo45r1-1226509825963 (accessed 25 February 2014).

Christie N (1986) The ideal victim. In Fattah E (ed.) From Crime Policy to Victim Policy: Reorienting the justice system: 17-30. New York: St Martin’s Press.

Constanza T (2012) Facebook page set up to help find Jill Meagher. Facebook, 26 September. Available at http://www.siliconrepublic.com/new-media/item/29397-facebook-page-set-up-to-hel (accessed 14 January 2014).

Constine J (2012) How big is Facebook’s Data? 2.5 Billion Pieces of Content and 500+ Terabytes Ingested Every Day. TechCrunch, 22 August. Available at http://techcrunch.com/2012/08/22/how-big-is-facebooks-data-2-5-billion-pieces-of-content-and-500-terabytes-ingested-every-day/ (accessed 25 February 2014).

Cook H (2012) Facebook warned to respect right to fair trial. The Sydney Morning Herald, 9 October. Available at http://www.smh.com.au/technology/technology-news/facebook-warned-to-respect-right-to-fair-trial-20121008-278g3.html (accessed 25 February 2014).

Cooper A (2012) Public hunt for missing woman. The Age, 24 September.

Cooper A, Brown A and Hingston C (2012) Fears grow for missing woman as other incidents reported. The Age, 25 September. Available at http://www.theage.com.au/victoria/fears-grow-for-missing-woman-as-other-incidents-reported-20120924-26hir.html (accessed 25 February 2014).

Davidson J, Grove-Hills J, Bifulco A, Gottshalk P, Caretti V, Pham T and Webster S (2011) Online Abuse: Literature Review and Policy Context. European Union: European Commission Safer Internet Plus Programme. Available at http://www.childcentre.info/robert/extensions/robert/doc/99f4c1bbb0876c9838d493b8c406a121.pdf (accessed 19 February 2014).

Deleuze G (1992) Postscript on the societies of control. October 59 (Winter): 3–7.

Dowsley A and Flower W (2012) Last steps in camera grab. Herald Sun, 26 September. Available at http://www.scribd.com/doc/130342182/Anthony-Dowsley-Wayne-Flower (accessed 10 September 2014).

Dowsley A (2012) Jill Meagher’s accused murder was warned of police probe. Herald Sun, 13 October. Available at http://www.heraldsun.com.au/news/victoria/jill-meaghers-accused-murderer-was-warned-of-police-probe/story-e6frf7kx-1226494761037 (accessed 5 September 2014).

Earley S (2010) Agenda Building in the New Media Age. Scribd, 8 March. Available at http://www.scribd.com/doc/28045798/Agenda-Building-in-the-New-Media-Age (accessed 20 February 2014).

Facebook Newsroom (2013) Key Facts. Available at http://newsroom.fb.com/Key-Facts (accessed 25 February 2014).

FBI (2012) Social Networking Sites: Online Friendships Can Mean Offline Peril. Available at http://www.fbi.gov/news/stories/2006/april/social_networking040306 (accessed 5 September 2014).

Feeley M and Simon J (1992) The new penology: Notes on the emerging strategy of corrections and its implications. Criminology 30(4):449-474.

Finneran A (2012a) Attacks on prostitutes were just for practice, it was only a matter of time before Bayley was ready to kill, and he did: Monster of Melbourne - Killer’s violent history. The Sun, 29 September.

Finneran A (2012b) We’ll kill Jill beast. The Sun, 1 October.

Flower W and Dowsley A (2012) One of six people seen on crucial CCTV comes forward as police probe abduction theory on missing Jill Meagher and plea for witnesses. Herald Sun, 27 September. Available at: http://www.news.com.au/national/one-of-six-people-seen-on-crucial-cctv-comes-forward-as-police-probe-abduction-theory-on-missing-jill-meagher-and-plea-for-witnesses/story-fncynjr2-1226482146903 (accessed 25 February 2014).

Ford C (2012) Can we please stop the victim blaming? Daily Life, 26 September. Available at http://www.dailylife.com.au/news-and-views/dl-opinion/can-we-please-stop-the-victim-blaming-20120925-26izn.html (accessed 24 February 2014).

Frances P (2009) Visual criminology. Criminal Justice Matters 78(1): 10-11.

Garland D and Sparks R (2000) Criminology, social theory and the challenge of our Times. British Journal of Criminology 40: 189-204.

Golan G (2006) Inter-media agenda setting and global news coverage: Assessing the influence of the New York Times on three network television evening news programs. Journalism Studies 7(2): 323-333.

Haggerty K and Ericson R (2000) The surveillant assemblage. British Journal of Sociology 51(4): 605-622.

Hewson C and Laurent D (2008) Research design and tools for internet research. In Fielding N, Lee R and Blank G (eds) The Sage Handbook of Online Research Methods: 58-79. Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore: Sage.

Hine C (2008) Virtual ethnography: Modes, varieties, affordances. In Fielding N, Lee R and Blank G (eds) The Sage Handbook of Online Research Methods: 257-270. Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore: Sage.

Innes M (2004) Signal crimes and signal disorders: notes on deviance as communicative action. The British journal of sociology 55(3): 335-355.

Jabour B (2012) Where is Sandrine? Brisbane Times, 11 October. Available at http://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/queensland/where-is-sandrine-20121010-27dbz.html (accessed 22 February 2014).

Jewkes Y and Yar M (2010) Introduction: The Internet, cybercrime and the challenges of the twenty-first century. In Jewkes Y and Yar M (eds) Handbook of Internet Crime: 1-15. Devon: Willan Publishing.

Jewkes Y (2011) Media & Crime. London: Sage.

Kaplan A and Haenlein M (2010) Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media. Business Horizons 53: 59-68.

Lariscy R, Avery E, Sweetser K and Howes P (2009) An examination of the role of online social media in journalists’ source mix. Public Relations Review 35: 314-316.

Lee M and McGovern A (2014) Policing and Media: Public Relations, Simulations and Communications. London: Routledge.

Livingstone S (2008) Taking risky opportunities in youthful content creation: Teenagers' use of social networking sites for intimacy, privacy and self-expression. New Media and Society 10(3): 393-411.

Lowe A (2012) ‘Trial by social media’ worry in Meagher case. The Sydney Morning Herald, 28 September. Available at http://www.smh.com.au/technology/technology-news/trial-by-social-media-worry-in-meagher-case-20120928-26pe4.html (accessed 25 February 2014).

Mangan J and Houston C (2012) The long arm of modern technology. The Age, 30 September.

Marketing Charts (2012) Facebook the Year’s Top Search Term, Most Visited Website. Watershed Publishing, 21 December. Available at http://www.marketingcharts.com/wp/direct/facebook-the-years-top-search-term-most-visited-website-25580/ (accessed 25 February 2014).

McCombs M (1997) Building consensus: The news media’s agenda setting role. Political Communication 14(4): 433-443.

McCombs M (2004) Setting the Agenda: The Mass Media and Public Opinion. Cambridge: Policy Press.

McDonald D (2014) The politics of hate crime: Neoliberal vigilance, vigilantism and the question of paedophilia. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 3(1): 68-80.

McGovern A and Lee M (2012) Police communications in the social media age. In Keyzer P, Johnston J and Pearson M (eds) The Courts and the Media: Challenges in The Era of Digital and Social Media: 160-174. Ultimo: Halstead Press.

McGuire M (2012) Technology, Crime and Justice: The Question Concerning Technomia, London and New York: Routledge.

Meraz S (2009) Is there an elite hold? Traditional media to social media agenda setting influence in blog networks. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 14: 682-707.

Milivojevic S (2011) Social networking sites and crime: Is Facebook more than just a place to procrastinate? In Lee M, Mason G and Milivojevic S (eds) Proceedings of the 4th Australian and New Zealand Critical Criminology Conference. Sydney: Sydney University and University of Western Sydney. Available at http://ses.library.usyd.edu.au//bitstream/2123/7380/1/Milivojevic_ANZCCC2010.pdf (accessed 10 September 2014).

Milivojevic, S (2012) The State, virtual borders and e-trafficking: between fact and fiction. In Pickering S and McCulloch J (eds) Borders and Transnational Crime: Pre-Crime Mobility and Serious Harm in the Age of Globalisation: 72-90. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave McMillan.

Mitchell N (2012) Jill Meagher was doing what thousands of ordinary young women do. 3AW, 28 September. Available at http://www.3aw.com.au/blogs/neil-mitchell-blog/jill-meagher-was-doing-what-thousands-of-ordinary-young-women-do/20120928-26ozg.html (accessed 25 February 2014).

Nankervis D (2012) Adelaide’s CBD to get extra closed close circuit television cameras to monitor city. The Australian, 24 October. Available at http://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/adelaides-cbd-to-get-extra-closed-circuit-television-cameras-to-monitor-citys-streets/story-e6frg6n6-1226502708372 (accessed 25 February 2014).

O’Reilly T (2004) The architecture of participation. O’Reilly Media, June. Available at http://www.oreillynet.com/pub/a/oreilly/tim/articles/architecture_of_participation.html (accessed 23 February 2014).

Oderberg I (2012) Social media has its place in busting crime. Herald Sun, 28 September.

Russell M (2012) Hate sites may affect Bayley’s trial. The Age, 10 October. Available at http://www.theage.com.au/victoria/hate-sites-may-affect-bayleys-trial-20121010-27czg.html (accessed 25 February 2014).

Russell M (2013) Jill Meagher murderer Adrian Bayley's appeal rejected. The Age, 21 October. Available at http://www.theage.com.au/victoria/jill-meagher-murderer-adrian-bayleys-appeal-rejected-20131021-2vvoq.html (accessed 22 January 2014).

Ryan E (2012) Who Could Have Prevented the Murder of Jill Meagher? (Hint: Not Jill Meagher). Jezebel, 1 October. Available at http://jezebel.com/5947964/who-could-have-prevented-the-murder-of-jill-meagher-hint-not-jill-meagher (accessed 25 February 2014).

Sayre B, Bode L, Shah D, Wilcox D and Shah C (2010) Agenda Setting in a digital age: Tracking attention to California Proposition 8 in social media, online news, and conventional news. Policy and Internet 2(2): 7-32.

Silvester J, Levy M and Oakes D (2012) ‘Mystery people’ found in CCTV vision of Jill Meagher. The Age, 25 September.

Snow D (2012) Leveson warns of trial by social media. The Sydney Morning Herald, 7 December. Available at http://www.smh.com.au/technology/technology-news/leveson-warns-of-trial-by-social-media-20121207-2aznx.html (accessed 25 February 2014).

Surette R (2007) Media, Crime and Criminal Justice: Images, Realities and Policies. Belmont: Thomson Wadsworth.

Taslitz A (2011) The incautious media, free speech, and the unfair trial: Why prosecutors need more realistic guidance in dealing with the press. Hastings Law Journal 62:1285-1320.

Tomazin F (2012) GPS plan to track arsonist. The Age, 11 November. Available at http://www.theage.com.au/victoria/gps-plan-to-track-arsonists-20121110-2958c.html (accessed 25 February 2014).

Wall D and Williams M (2011) Using the Internet to research crime and justice. In Davies P, Francis P and Jupp V (eds) Doing Criminological Research: 262-280. Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore, Washington DC: Sage.

Wallace B (2011) Online Privacy Survey: Conducted for Hungry Beast. Sydney: McNair Ingenuity Research.

Wilson R, Gosling S and Graham L (2012) A review of Facebook research in the social sciences. Perspectives on Psychological Science 7(3): 203-220.

Young A (1996) Imagining Crime. London: Sage.

[1] A ‘signal crime’ is defined by Innes as ‘any criminal incident that causes change in public behaviour and/or beliefs... They are crimes that “signal” the presence of risk to people, and function as warning signals about threats and dangers’ (Innes 2004: 162).

[2] A notable case is Sandrine Jourdan, missing since July 2012, who’s missing person Facebook page had ‘only’ 2,000 ‘likes’ eight months after her disappearance. When her sister called TV stations to help publicise her disappearance, journalists asked ‘what is so special about her?’ (Jabour 2012).

[3] While there are a range of definitions for ‘troll’, the term typically refers to a type of internet user who abuses or taunts others in the online environment for their own enjoyment (Bishop 2014).

[4] At the time of writing this paper the main hate page ‘Publicly hang Adrian Ernest Bayley’ remained active, with nearly 42,000 members as of February 2014. The group was a vocal critic of Bayley during the trial, subsequently turning its attention to promoting tougher sentences for violent offenders, the return of capital punishment and ‘compulsory CCTV on all major Melbourne streets’. As of September 2014 the page was no longer on Facebook.

[5] For some notable exceptions see Brice (2013).

[6] For example, limited space prevented us from engaging with important issues such as the socio-political implications of social media and the e-democratisation of media technologies, something we seek to explore in future articles.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/IntJlCrimJustSocDem/2014/21.html