|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy |

Julia Quilter[1]

University of Wollongong, Australia

Russell Hogg

Queensland University of Technology, Australia

|

Abstract

The fine is the most common penalty imposed by courts of summary

jurisdiction in Australia, and fines imposed by way of penalty notice

or

infringement notice are a multiple of those imposed by the courts. The latter

are being used for an increasing range of offences.

This progressive

‘monetization of justice’ (O’Malley 2009b) and its effects

have passed largely unnoticed. The

enforcement of fines has, in most parts of

Australia, been passed from the justice system to government revenue agencies

with barely

any public scrutiny or academic analysis. Sentencing councils, law

reform commissions and audit and ombudsman offices have completed

inquiries on

fines, some of them wide-ranging and highly critical of existing arrangements.

Yet, these inquiries arouse little public

or media interest and, partly in

consequence, there has been little political will to tackle fundamental problems

as distinct from

tinkering at the margins. After surveying the theoretical

literature on the role of the fine, this paper considers the neglected

question

of fines enforcement. We present three case studies from different Australian

jurisdictions to highlight issues associated

with different models of

enforcement. We show that fines enforcement produces very real, but often

hidden, hardships for the most

vulnerable. Despite its familiarity and apparent

simplicity and transparency, the fine is a mode of punishment that hides complex

penal and social realities and effects.

Keywords

Fines; penalty; sentencing; enforcement; driving while disqualified;

secondary offending.

|

Please cite this article as:

Quilter J and Hogg R (2018) The hidden punitiveness of fines. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 7(3): 9-40. DOI: 10.5204/ijcjsd.v7i3.512.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Licence. As an open access journal, articles are free to use, with proper attribution, in educational and other non-commercial settings. ISSN: 2202-8005

The fine is the most common penalty imposed by criminal courts in Australia and most other high-income countries, with the notable exception of the United States of America (USA) (Faraldo-Cabana 2017; O’Malley 2009a). Yet, no penalty has received less critical examination in the academic literature. Fines being so common, much attention is devoted to technical aspects of their administration from the point of view of efficiency. Indeed, in Australia, legislative modification of fines enforcement processes seems to be constantly in train. Sentencing councils, law reform commissions, and audit and ombudsman offices have also completed inquiries on fines, some of them wide-ranging and highly critical of existing arrangements (see, for example, Audit Office of NSW 2002; NSW Law Reform Commission (NSWLRC) 2012; NSW Ombudsman 2009; NSW Sentencing Council 2006; Sentencing Advisory Council, Victoria 2014). Yet, these inquiries arouse little public or media interest and, partly in consequence, there has been no political will to tackle fundamental problems as distinct from tinkering at the margins. Political inertia is not aided by the paucity of academic interest, especially when we compare it to the extensive literature on incarceration, the most consequential penalty but one imposed in only a small minority of cases.

Critical public interest in the fine has mainly focused on the problem of imprisonment for default, where an ostensibly lenient penalty converts into a harsh penal outcome because the offender is unable or unwilling to pay. But as jurisdictions in Australia and elsewhere removed imprisonment for default, public interest in the fine waned. At the time (1987) this occurred in New South Wales (NSW)—largely as a result of a sustained political campaign for reform following the severe bashing of a young fine defaulter named Jamie Partlic in a maximum-security prison—Brown warned:

.... that the struggle is a continuing one; that the problems of imprisonment for fine default will not ‘cease’ or ‘be fixed up’ with the adoption of a particular reform package; that continual monitoring is required; that various other ‘alternatives’ and reforms will throw up their own problems; ...

The struggle around imprisonment for fine default requires neither the abstract demand for ‘abolition’ nor the acceptance that any change is an improvement, but an eye to the detail, a knowledge of the way the system currently operates, an ability to recognise how changes in one sector will react or affect other sectors. (Brown 1987: 84-85)

It is well past time to heed Brown’s warning and to reawaken critical scholarly (and public) interest in the fine and its impacts. There are at least three reasons for doing so, quite apart from simply redressing its long-standing neglect in the critical literature.

First, use of the fine has soared since the 1980s. A crucial development has been the growing reliance on out-of-court, infringement or penalty notice provisions as an alternative to criminal prosecution for a constantly growing number of offences. Little is known of the full range of agencies involved in administering these regimes, of their policy frameworks or of how they exercise their discretionary powers.

Secondly, the human impacts on those affected is little understood. Because ‘only’ money is at stake rather than personal freedom, the assumption is too readily made that fines are inherently lenient, making evidence of its effects unnecessary. Where mandatory sentencing regimes are highly controversial, it is overlooked that fines imposed under administrative fixed penalty regimes (over 95% of the total), are mandated punishments that take no account of the circumstances of the offence or the financial means of the offender, in addition to denying the individual traditional procedural safeguards like the presumption of innocence and a court hearing.

A third reason for devoting more attention to fines is that fines enforcement has recently undergone significant reorganisation in many jurisdictions. The changes are generally assumed to be benign because they effectively remove imprisonment as an option in the event of default. However, the actual impacts on different groups have received limited public or academic attention. Where enforcement in the past has tended to be the responsibility of the justice system, the current trend has been to transfer it to a separate administrative agency, with the primary emphasis on debt recovery. Innovative measures, procedures and sanctions have been introduced in response to long-standing problems of default and low recovery rates. These processes can be highly consequential for some people. Their administrative character has sheltered them from public scrutiny at the same time as it often renders them peculiarly insensitive to the hardships imposed on the vulnerable. Publicly accessible data relating to enforcement and its impacts are also extremely limited, scattered and inconsistent.

This article is in two parts. In the first, we rehearse the widely noted attractions of the fine as a penalty, summarise some of the data indicating the scale and growing use of the fine, briefly survey the theoretical literature on the role of the fine with a particular focus on the recent analysis by eminent Australian academic, Professor Pat O’Malley, of the place of the fine in consumer societies and, finally, turn to the neglected question of enforcement. The second part considers enforcement issues in detail by way of three case studies looking at different Australian jurisdictions.

We use the term ‘fine’ to refer to both court-based and out-of-court financial penalties. A growing number of offences are now subject to infringement or penalty notice provisions. These ‘opt-in’ measures imposed by police and other agencies require the ‘offender’ to pay a nominated fine for the infringement in question or elect a court hearing, usually with the prospect that, if unsuccessful, the penalty will be increased and court costs incurred. Nomenclature relating to these out-of-court fines varies. ‘Penalty notice’, ‘infringement notice’ and ‘expiation notice’ are amongst the terms used in one or more jurisdictions. We will generally stick with the term ‘penalty notice’ for convenience, using the other terms only where it is warranted by the specific context. Some choose to distinguish fines imposed by courts from out-of-court fines, referring to the former as ‘penal’ fines and the latter as ‘regulatory’ fines or ‘regulatory penalties’. We choose not to make any clear-cut distinction of this kind. The main reason is that no coherent or principled basis is provided in Australian law for the distinction or is relied upon to guide decisions to make newly created offences subject to administrative penalties or, what is more common, to remove offences hitherto dealt with by the courts into penalty notice regimes. From what one can tell, the actual penalties imposed do not necessarily vary in any consistent way—that is, being necessarily more lenient in the case of penalty notices than when imposed by a court—as might be expected. Nor, when it comes to enforcement processes and sanctions for default, is any consistent distinction drawn in most of the new state regimes, which, in some states (like NSW), simply homogenise the different financial penalties and other fees (like court fees), treating them as debt.

Fines are widely viewed as the ideal penalty, a simple, ‘quick, efficient, flexible, effective, and cheap form of punishment ... easily understood ... and readily adjusted to reflect the seriousness of the offence and the circumstances of the offender’ (Sentencing Advisory Council, Victoria 2014: 9). They are readily understood as imposing a hardship but one which is (supposedly) not excessively disruptive to the lives of wrongdoers. Unlike other penalties, they are also reversible in the event of error. Fines reduce the fiscal burden on the criminal justice system and the state and, as a source of revenue, may even support other government programs and services. These factors have made fines popular with judges, magistrates (McFarlane and Poletti 2007; Sentencing Advisory Council, Victoria 2014), administrators and politicians, and penal thinkers from the English utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham to Pat O’Malley. Fines do not intrude on the general liberty of the subject and tend to avoid or minimise the stigmatising effects associated with other penalties.

As Pat O’Malley (2009b) argues, these qualities have enabled money penalties to assume a central role in the regulation of vast swathes of social and economic life in modern societies. Should such regulation be undertaken by almost any other imaginable means, he suggests, it would carry prohibitive financial, and politically unacceptable, costs. Court-administered fines allow expensive, time-consuming legal procedures to be curtailed, support the extension of summary proceedings in place of trial on indictment, often dispense with the need for defendants to attend court and encourage guilty pleas. Infringement or penalty notice regimes take a vast range of offences out of the courts entirely, permitting mass violations to be processed at low economic and political cost.

In their classic 1939 study Punishment and Social Structure, Rusche and Kirchheimer identified the factors driving the growing ascendancy of the fine in the twentieth century: fines achieved a penal effect without cost to the state; they ensured labour was not removed from the economic system; and the state and philanthropic organisations were relieved of the burden of supporting offenders’ families. They were, however, also mindful of the difficulties that stood in the way of ‘the full rationalization of the penal system through the introduction of fines’ (Rusche and Kirchheimer 2009 [1939]: 169), most importantly, the enforceability of fines against the indigent and how to maintain a semblance of equal justice if fines were converted to imprisonment in the case of those unable to pay.

In or out of court, fines are now, and have been for some time, by far the most frequently imposed penalty in Australia and many other countries. Over 60 per cent of offenders sentenced in Australian criminal courts each year receive a monetary sanction as their principal penalty (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2017). It is rare for higher criminal courts to fine offenders, except as a secondary penalty, but Magistrates Courts commonly impose fines for assaults, thefts, drug offences, property damage and public order offences as well as motoring offences. The range of offences subject to penalty notice regimes is also constantly growing. In NSW 17,000 offences under approximately 100 legislative instruments are subject to penalty notice provisions (NSW Sentencing Council 2006: 76). In many jurisdictions (including NSW and Victoria) police now also have the discretion to proceed against some theft, wilful damage and public order offences by way of penalty notice or what in NSW is called a ‘criminal infringement notice’ (see, for example, Criminal Procedure Act 1986 (NSW) s 332 and Criminal Procedure Regulation 2017 (NSW) Sch 4). Equally, the range of agencies that can impose these penalties has expanded and the digital technologies used in the detection and administration of violations (for example, speed cameras, red light cameras, use of iPads by public transport officers) have become more sophisticated, contributing to the steep growth in the number of infringements issued. This massive downward classification of offences and curtailment of the courts’ role has largely escaped public notice and has been the subject of little critical inquiry (see Fox 1995a, 1995b for an important early exception in the Australian context).

Out-of-court fines are imposed on a vast scale compared to court-based fines. Currently around 2.8 million penalty notices are issued each year in NSW compared with roughly 120,000 sentences of all kinds imposed by local courts. That translates into more than 20 penalty notices for every sentence imposed by a NSW court (NSWLRC 2012: 1). In the mid-1990s, Fox found that the ratio of infringement notices to all court-imposed penalties (not just fines) was 7:1 in Victoria (1995a, 1995b). In 2012-13, almost 6 million penalty notices were issued in Victoria by over 120 different agencies, while there were 114,000 court-imposed fines (Sentencing Advisory Council, Victoria 2014: 62). That is a ratio of around 50 penalty notices for every fine issued by a court, conveying some sense of the colossal growth in use of out-of-court penalties in that state since the early 1990s. Critical scholarship on fines has seriously lagged behind their growth in number and significance, both over the longer period of the twentieth century and in the more recent past.

In 1983, Bottoms pointed out that the prominent and growing role of the fine was one of the most ‘neglected features of contemporary penal systems’ (Bottoms 1983). He argued that it was also a trend that sat uncomfortably with the then popular ‘dispersal of discipline’ thesis. Fines, unlike community-based sanctions, were devoid of any supervisory element or normalising purpose, yet penal analysis at the time was centrally preoccupied with the net-widening effects of community sanctions, what was depicted as an insidious extension of disciplinary controls out of the prison and into society. The dominant narrative since the 1980s has emphasised a ‘punitive turn’: the return to centrality of the prison; rocketing imprisonment rates in many countries; and a widening cultural shift in which the overt hardening of penal policies and attitudes is driven by a more heated, openly moralistic and emotional public discourse (see, for example, Garland 2001). Again, the continuing, indeed accelerated, expansion in reliance on the fine since the 1980s is not readily accounted for (or usually noticed) in the literature on the ‘punitive turn’. Far from ‘heating up’, the fine as a penalty ‘cools’ and de-dramatises; it drains punishment of emotional and cultural meaning. As Bentham (1843) pointed out long ago, the fine lacks the element of ‘exemplarity’, of ‘spectacle’, of other punishments. It is, as he said, simply the transfer of a monetary sum that has nothing to distinguish it from other ordinary payments. This is a major reason why fines are rarely imposed by higher criminal courts for serious crimes of a deeply personal nature like violent or sexual crimes, where putting a monetary value on the offence appears to be subversive of cherished notions of moral personhood (Young 1989). It also helps to explain the lack of attention accorded the fine in public and academic discourse.

There are, nonetheless, important exceptions to this neglect (Beckett and Harris 2011; Carlen and Cook 1989; Faraldo-Cabana 2014, 2017; Fox 1995a, 2005b; Harris 2016; Harris, Evans and Beckett 2010; Hogg 1988; Katzenstein and Waller 2015; O’Malley 2009b; Young 1989; and the 2011 special issue of Criminology and Public Policy; for more empirical studies in the Australian context, see Brown et al. 2013; Lansdell et al. 2012, 2013; Saunders et al. 2013, 2014; Walsh 2005).

In particular, Pat O’Malley offers a refreshingly original analysis of the fine and other monetary penalties. He underlines the absolute centrality of money as an instrument of contemporary governance that spans (and blurs) the traditional civil/criminal legal divide which has set boundaries to so much punishment and society scholarship. O’Malley argues that, as ‘the West’ entered its post-war age of affluence, the emergence of a more prosperous and disciplined citizenry delivered the conditions in which monetary penalties could assume the more central role envisaged for them by classical liberal thinkers like Bentham and commended more recently by law and economics theorists like Becker and Posner (O’Malley 2011: 550). With the rise of consumer societies, money is ubiquitous, the great majority of people enjoy surplus income and markets reach into nearly every pocket of existence. The problems identified in earlier times as holding back mass use of the fine—namely, the inability of the poor to pay and the consequent reversion to some other penalty (usually imprisonment) for defaulters—have largely been overcome. People are led to regard fines in much the same light as they do other routine costs of modern living like commodity prices, taxes, licence fees, tolls, and so on. Stripped of moral meaning or any element of condemnation, the penalty becomes literally just another price. The expanding reliance on money penalties could, therefore, be seen to reflect a further and important dimension in the advance of neo-liberal governmental logic in which market principles—user pays, efficiency, cost recovery—penetrates the heartland of state responsibility.

Pivotal to the role of money sanctions is that, alone among modern punishments, they effectively dispense with the requirement that the offender bear the burden of the penalty. Australian courts, like courts in many other countries, accept that it is not wrong in principle to impose a fine on the basis that some other party will pay it (R v Repacholi (1990)). Jurisdictions that reject this have, nevertheless, found it impossible to enforce, a necessary consequence of a penalty based on an abstract, universal medium like money which takes increasingly diverse forms and where precisely sourcing payment and tracking its movements present almost insurmountable obstacles. The law requires payment, but is indifferent to who makes it. Unlike other penal sanctions, which are personal in nature, the costs imposed by money sanctions are transferable: by having payment made by another person (like a family member) or from pooled resources like those of a household or, in the case of a business, treating it as a cost that is passed on in the form of increased prices. The cost is transferable in another, more limited, sense: the offender may borrow from another person to pay or pay by credit card. This converts the public obligation into a private contractual one, a private debt. This suggests the importance of considering the nature, role and impact of fines from the standpoint of not only the rise of consumer society but also of its perennial counterpart: personal debt.

O’Malley stresses at the outset that his analysis is primarily concerned ‘with money as a tool or technology of government—with how money is imagined and intended to be used rather than with questions of actual impact on the subjects of government’ (2009b: ix). His focus is limited, therefore, and not, for example, particularly concerned with the lived experience of financial penalties, although it is difficult to escape the impression that he sees money penalties in largely positive terms, what he refers to at one point as a ‘tolerant and non-repressive’ form of risk governance (O’Malley 2011: 550). This is useful as a corrective to reflex dystopian forms of analysis, but it does rest on certain unexamined assumptions about the workings of fines. Fines may, as Bentham stressed and O’Malley agreed, avoid the element of spectacle, of ‘exemplarity’, in punishment and thus be less stigmatising of offenders, but does this mean they are necessarily more lenient in their effects? Could it be that this feature, which also justifies curtailing conventional legal safeguards (including handing the power to punish to executive agencies), serves to obscure the manifold impacts of the fine? The claims that fines are a simple, flexible, efficient, effective and inexpensive penalty certainly have a surface plausibility that drives their widespread use, but how far are these advantages borne out in practice? Has a cosy complacency set in around the fine that obviates any felt need to examine its workings? Is it regulatory efficacy or administrative expedience that sustains commitment to the fine?

It would be foolish to deny that money penalties and their unique transferability certainly provide pathways away from stigmatising entanglement in the criminal justice system for many. Alternatively, this of itself might be a cause for concern where it reflects undue leniency towards corporations or the wealthy who could be said to escape ‘justice’ simply because of their capacity to pay. This is a subject worthy of careful inquiry, bearing in mind that these parties are the least affected by financial penalties, as they are by other forms of punishment.

We do know from research and official inquiries that fines have disproportionate and serious adverse impacts on disadvantaged sections of the community: Indigenous Australians, the young, homeless, the welfare dependent, mentally ill people, those with intellectual disabilities and prisoners. These groups are more vulnerable to being fined in the first place and to accruing multiple fines. They are less likely to be able to pay fines or to negotiate the processes available to contest them or otherwise mitigate their impact. Literacy and numeracy problems, language difficulties, housing insecurity and residential transience ensure that many will fall foul of inflexible administrative systems that are insensitive to the circumstances of the poor and marginal (official correspondence not received or not understood, inability to provide relevant documentation or utilise on-line systems that are heavily dependent on complex forms and written information). For the most disadvantaged, criminal justice debt simply compounds civil debt problems and other hardships, confronting people with often impossible choices about which bills to pay. Paying a fine will likely appear less urgent to a household confronted with the prospect of having the electricity disconnected, of not being able to put food on the table or of eviction for failing to pay rent, thus requiring the longer-term consequences of default to be simply put out of mind. Or, paralysis or fatalism may set in where people are overwhelmed by the cumulative stresses in their lives. To the extent that fines, as debt, are transferable for the most disadvantaged, this may simply exacerbate household poverty, tensions and conflict. Involvement with the criminal justice system may be escalated, whether through secondary offending (driving while licence suspended), turning to acquisitive crime or due to other instability and disorder caused by multiple disadvantage (drug and/or alcohol problems, ‘sleeping rough’, violent conflict, and so on) (Cunneen and Schwartz 2009; NSW Ombudsman 2009; NSW Sentencing Council 2006). Indigenous Australians are hit particularly hard by these dynamics in which financial penalties, far from providing an alternative to punitive justice, are more likely to afford pathways into the punitive reaches of the system (Cunneen and Schwartz 2009). A 2008 survey found that over 40 per cent of the Aboriginal community in NSW had outstanding debts with the State Debt Recovery Office (Elliott and Shanahan Research 2008). A NSW Ombudsman report (2009) found that nine out of ten Aboriginal persons issued with a criminal infringement notice (CIN) failed to pay in time and were referred for enforcement. As the NSW Ombudsman (2009: 50) pointed out, ‘debts from CINs could add to the cumulative stresses associated with poverty in communities already struggling to cope with chronic debt’.

Because fines as debt merge with the other sources of financial hardship in people’s lives, the particular impacts are masked. They are frequently serious and potentially affect quite large numbers of people. Consider that the 2016 Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey found over 12 per cent of Australian households did not have $500 in savings to meet an emergency (Wilkins 2016: 85-86). Most fines imposed by NSW local courts are between $200 and $500 (all monetary amounts in this article are in Australian dollars) and penalty notice fines frequently exceed court fines. It should also be noted that a contemporary capitalist political economy—a consumer society—runs on high and steepening levels of private debt, growing financial insecurity and the normalisation of precarious employment and economic conditions for growing numbers of people, what Standing refers to as the rise of the ‘precariat’ (2011).

Sentencing principles require a court to consider the financial means of an offender when imposing a fine and to avoid imposing a fine that he or she is incapable of paying, although this is commonly accompanied by the qualification that it is only necessary when the information is reasonably and practically available (see, for example, Fines Act 1996 (NSW) s 6). The evidence is that various factors—caseloads and workload pressures, judicial attitudes, difficulties with verifying offender means—ensure that the sentencing principle is honoured in the exception by the courts and also that courts, from want of knowledge or alternatives, frequently impose fines on offenders who already have outstanding fines that they cannot pay (NSW Sentencing Council 2006: 45-48; also see Walsh 2005). Of course, the assessment of means plays no role in the imposition of the vast majority of fines which are imposed by way of penalty notice.

The problems that restricted use of the fine in earlier times—especially its enforceability against the indigent—have not disappeared, but this has not inhibited its growth. Claims about the efficacy of the fine are belied by the continuing evidence of high default rates and low recovery rates (Freiberg and Ross 1999: 166; NSW Sentencing Council 2006: 42-44; Sentencing Advisory Council, Victoria 2014: xiii, 73). Fines may be easy to impose but getting people to pay them remains a major problem (Donnelly, Poynton and Weatherburn 2016). Indeed, enforcement has necessarily assumed growing significance as the number and money value of violations has risen to massive levels. In NSW in 2015-16, the total value of penalty notices issued by agencies for which data are published amounted to almost half a billion dollars. While 75 per cent of penalty notices and 25 per cent of court fines in NSW are finalised without further enforcement action, that leaves cases numbering in the hundreds of thousands potentially subject to enforcement action of various kinds.

It is an inescapable fact that the fine is a fundamentally inegalitarian penalty. Efforts over a long period to grapple with this (Garton 1982: 102-103) only mitigate the impact of inequality; they cannot remove it. Measures seeking to address it at source—day or unit fine systems—present other problems (see Ashworth 2005: 304-305) that have prevented adoption in most jurisdictions. In any case, day and unit fine systems are confined to the small minority of fines imposed by the courts. The inherent unfairness is underscored by the evidence that much default stems from an inability rather than an unwillingness to pay (Moore 2003; NSW Sentencing Council 2006: 19-20, 88-89; Walsh 2005). Abolishing imprisonment for default has removed the most visible marker of unfairness and inequity, but perhaps only to displace the problems into the more hidden, arcane domains of administrative practice under novel enforcement systems that produce their own punitive effects.

The trend in most Australian jurisdictions, and many others, has been to centralise and rationalise fines enforcement in an administrative agency separate from the justice system. In some jurisdictions (NSW and Queensland, for example), enforcement responsibility has been passed from the criminal justice system to state revenue agencies (in NSW, Revenue NSW). The core emphasis is on ‘risk-based recovery’ which is said to balance penal concerns with efficiency considerations. Graduated administrative sanctions are applied to outstanding fines, treating them as debts and sometimes assimilating them to other forms of state debt. ‘Risk-based recovery’—managing the risk of non-payment—has subsumed the risks which attract the monetary penalties in the first place. Risks are simply homogenised as debt. The many actual and potential consequences of current enforcement regimes are invisibilised by the logic of ‘financial risk management’ in which defendant morphs into debtor and principles of justice (due process, equality, proportionality, transparency, and so on) no longer apply.

We now turn to three case studies relating to different modes of enforcement action taken against fine defaulters in various Australian jurisdictions. We show how punitiveness in different forms is an endemic feature of the new enforcement systems.

On 4 August 2014, a young Aboriginal woman, Ms Dhu, died at Hedland Health Campus in Western Australia (WA) whilst she was in police custody. Ms Dhu had been imprisoned for four days to cut out fines (her largest being $1,000). The coronial inquest into her death made a number of recommendations including ‘... that the Fines, Penalties and Infringement Notices Enforcement Act (WA) (section 53) be amended so that a warrant of commitment authorising imprisonment is not an option for enforcing payment of fines’ (Inquest into the Death of Ms Dhu 2016: 151).[2] Ms Dhu’s death has been the subject of widespread publicity and her mistreatment whilst in custody has been the subject of media outrage (Brull 2016; Perpitch 2016), of community campaigns (First Nations Deaths In Custody Watch Committee Inc 2017), of research including into the WA fines legislation (Klippmark and Crawley 2017; Porter 2015, 2016) and of reference in government reports (Australian Law Reform Commission (ALRC) 2017a; Office of the Inspector of Custodial Services 2016).

As discussed in the Introduction, most criminal justice scholarship has focused on imprisonment. It is not surprising, therefore, that a death in custody when the deceased was detained for fine default is one of the few occasions when public interest is shown in relation to fines enforcement. Western Australia is the only Australian jurisdiction that does not incorporate the principle that imprisonment for fine default is a ‘last resort’ (Sentencing Advisory Council, Victoria 2014: 6.3.24). Without repeating the focus solely on incarceration, this case study considers the framework of the WA fines legislation in conjunction with important policy and legal changes and practices that have created ‘incentives’ to pay back fines by way of imprisonment. Without condoning the use of imprisonment for fines enforcement, we nevertheless raise concern over the failure to provide similar incentives for paying back fines via Community Service Orders (CSOs) or to identify the interrelationship with other forms of enforcement. This underlines Brown’s (1987) argument, cited in the introduction, that we must consider how changes in one area affect other parts of the fines enforcement system.

The imposition and enforcement of fines in WA is governed by the Fines, Penalties and Infringement Notices Enforcement Act 1994 (WA) (‘the WA Act’) and the Fines, Penalties and Infringement Notices Enforcement Regulations 1994 (WA) (‘the WA Regulations’).[3] The Act distinguishes enforcement for court-imposed fines from those based on infringement notices, with only the former being enforced by way of imprisonment (WA Act s 29). Fines imposed by infringement notice are subject to civil enforcement measures only, such as suspension of a driver’s licence or seizure of property under a warrant.

Part 4 of the WA Act sets out the enforcement of court fines. A reading of this Part, with the graded hierarchy of options (from least to most serious) in relation to default gives the appearance of orderliness and fairness. Thus, an offender, after receiving a fine, can pay it (s 32(1)(a)) or apply for a ‘time to pay order’ (s 32(1)(b)). Where the offender obtains a time to pay order, contravention may lead to cancellation of the order and the fine being ‘registered’ (s 36). Once registered, the Registrar may implement the four-tiered enforcement options: make a ‘license suspension order’ (s 42(3)(a)); issue an ‘enforcement warrant’ (s 42(3)(b)); issue an order to attend for Work and Development (WDO) (s 42(3)(c)); and issue a warrant of commitment for imprisonment (s 42(3)(d)). The Act requires the enforcement process to follow this tiered system (ss 47(2) and 53(1)) from least to most serious.

On its face, the system thereby promotes an administratively driven yet apparently ‘fair’ series of steps. The tiered options also suggest considerable time will elapse before a warrant of commitment (or WDO) may be contemplated, giving the appearance that an offender is afforded ample opportunity to make good the debt. For example, the second tiered option, ‘enforcement warrant’, gives the Sheriff statutory authority to undertake a number of measures including the seizure and sale of personal property (s 71(2)(b)) and seizure of money to apply to the debt (s 71(2)(b)), with each step taking considerable time to enforce. Only failing this can a WDO be used (s 47(2)) and failing this option (for example, for breaching the WDO) qualifies a warrant of commitment for imprisonment to be used. This suggests that, even in WA, imprisonment is a de facto mechanism of ‘last resort’ for fines enforcement.

In practice, this tiered system may be circumvented as the Registrar has an ultimate discretion under the WA Act to implement the most ‘effective’ method of recovering the amount owed. This discretion may be exercised on the Registrar’s own accord or as a result of an offender making application under s 55D.[4] An offender can apply to convert the unpaid fines to Community Work (that is, a WDO[5]) or to imprisonment. To do so, the offender must satisfy the two criteria in the 55D form:[6] ‘I have no financial capacity to pay’ and ‘I have no assets (goods or property)’. Successful application allows the Registrar to avoid the otherwise-required earlier enforcement steps (s 47(2)).[7] Enquiries to the WA Fines Enforcement Registry (email correspondence with Fines Contact Centre, 23 February 2016) confirm that an offender can also apply for conversion of unpaid fines into a term of imprisonment.[8] For this option, in addition to the financial/asset based criteria, the offender is required to be physically or mentally incapable of completing a WDO. The Registrar can then use the overriding discretion to implement the most ‘effective’ mechanism under s 55D.

Leaving aside the extraordinary fact that, where an offender applies to convert the fine to imprisonment, this could see people unable to work because of mental or physical health-related issues being incarcerated, there are two recent changes that have meant conversion of fines to imprisonment may be a more appealing option for a fine defaulter in WA.

First, in 2008 the then Labor Government introduced changes to the WA Act (specifically s 58(3)) which allowed imprisonment terms for fine default to be served concurrently, meaning that a fine defaulter will only be imprisoned for their highest fine. This was not the original intention of the amendment which was to allow periods of imprisonment for fine default to be served concurrently with sentences for other offences only, but not concurrently with imprisonment for other fines (see McGinty 2006). However, the new (and current) s 53(8) provides that: ‘The period of imprisonment specified in a warrant of commitment is concurrent with any other period or term of imprisonment that the offender is serving or has to serve [emphasis added]’.[9] Thus, the terms are not confined to terms of imprisonment for offences other than those for fine default.

In WA, an offender erases $250 for each day of incarceration (WA Act s 53(3)(a); WA Regulations s 6BAA) with a minimum period of imprisonment being one day irrespective of the outstanding debt (s 53(3)). Section 53(3)(a) in effect stipulates that the number of whole days to be served is calculated by dividing the amount owed by $250 and then rounding down to the nearest whole number of days. For example, if $499 was owed, 499/250 = 1.996, which is rounded down to one day.

In this context, we need to also consider the Registrar’s practice in issuing a warrant of commitment. Our correspondence with the Fines Enforcement Registry (email correspondence with Fines Contact Centre, 23 February 2016) confirmed that an individual warrant is created for each court fine, meaning that multiple fines are not put on the one warrant. Since the 2008 amendments, this means that only the highest amount on a warrant of commitment is required to be served. For example, if an individual has 10 different fines, each in the amount of $250, this amounts to $2,500 in total, a sum that would take an individual even in full-time work a number of weeks to pay off. However, as the highest fine is $250 and the rate is $250/day of imprisonment, it would only take a single day to completely wipe out the totality of the fines. As the Office of the Inspector of Custodial Services (2016: 9 [3.8]) indicated, ‘[t]he benefit for fine defaulters serving time concurrently for multiple fines is that large amounts of penalties owed can essentially be paid off very quickly. For example, one woman served only two days in 2010 – for over 100 separate fines totalling just under $29,000. Her largest fine was $844’.

Added to these ‘incentives’, in 2009, a more punitive policy for enforcing CSOs was introduced. Prior to 2009, a ‘three omissions policy’ applied which meant that an offender would only breach a CSO if s/he failed to report/comply with a CSO on three consecutive occasions. For example, an offender who missed two consecutive work days but attended on the third, would technically comply with the order even though significantly delaying the completion of it. In 2009 the policy was modified:

If a person misses his community work once, he receives a warning; and, if he gives an excuse, it will have to be given within 24 hours. If a person misses it twice—it need not be a consecutive omission—the presumption will be that he has breached, and he will be sent back to court for re-sentencing. If he misses it three times, he will know that he will automatically be breached. (Porter 2009: 4833b-4834a)

WDOs fall under the general policy for CSOs. This policy change appears to have been a further significant contributing factor in the proliferation of fine defaulters since 2008 choosing to enter prison to cut out fines (Western Australia (WA) Labor 2014). The statistics certainly demonstrate that this is so (WA Labor 2014: 5), with the number of prison receptions for fine default alone dramatically increasing since 2008:

Year No. of receptions into Prison

2008 194

2009 666

2010 1613

2011 1115

2012 1127

2013 1358

A more recent report by the Inspector of Custodial Services (2016: 6 [3.4]) qualifies this data, suggesting that, while receptions for fine default remain well above 2008 levels, the number of fine default receptions for the financial year 2014/2015 has sharply decreased.

The impact of converting fines to imprisonment has overwhelmingly been borne by women and Aboriginal people. In 2013, one in every three women entering the prison system did so solely to clear fines (WA Labor 2014: 2). In relation to Aboriginal people, between 2008 and 2013, the number incarcerated for fine default has increased from 101 to 590, a 480 per cent growth (WA Labor 2014: 2). The number of Aboriginal women going to jail for fine default has soared by 576 per cent, from 33 in 2008 to 223 in 2013 (WA Labor 2014: 9). Supporting these findings, the Inspector found that ‘[f]emales make up approximately 15 per cent of the total prison population yet constitute 22 per cent of the fine defaulter population. Overall, women have been consistently over-represented in the fine defaulter population’ (Inspector of Custodial Services 2016: 12 [4.2]). Further, of female fine defaulters, the majority are Aboriginal (64%) (Inspector of Custodial Services 2016: 13 [4.3]). These are disturbing figures given that Aboriginal people, and Aboriginal women specifically, are already heavily overrepresented in the criminal justice system (ALRC 2017a).

While we have pointed to the above legislative and policy changes that may have led to increased incarceration for fine default, we know little about the individual circumstances of these fine defaulters and why imprisonment has become apparently a first resort. The s 55D form ‘Request to Convert Court Fine to Imprisonment’ (see Appendix 1) provides little guidance on these issues or possibilities for recording relevant data. The form requires the fine defaulter to ‘tick’ appropriate boxes out of: ‘I have no financial capacity to pay’; ‘I have no assets (goods or property)’; ‘I am physically incapable of completing a Work and Development Order’; ‘I am mentally incapable of completing a Work and Development Order’; and ‘I am a sentenced prisoner/on remand at _______ Prison, and my earliest release date is __/__/__’. There is no place on the form to provide any detailed reasons for the application aside from box ticking. There is not even room to indicate what type of physical or mental incapacity the fine defaulter suffers.[10]

We know from the Inspector’s Report (Inspector of Custodial Services 2016) that people with ‘lower-paying or nonprofessional jobs and the unemployed make up a high proportion of incarcerated fine defaulters’ (2016: 14 [4.4]). In relation to female fine defaulters, 73 per cent were considered unemployed whereas for men, only 10 per cent were considered unemployed (2016, 14 [4.6]). Furthermore, 52 per cent of Aboriginal unemployed fine defaulters are female, leading the Inspector to conclude that ‘[t]his evidence supports the notion of Aboriginal women historically being the most vulnerable to fine default imprisonment’ (Inspector of Custodial Services 2016: 14 [4.7]).

While we have little information about the reasons why fine defaulters, particularly Aboriginal women, are choosing (or being forced) to pay off fines by way of imprisonment, we note interviews with three fine defaulters undertaken by The Australian newspaper reporters (Taylor and Laurie 2015). The first accrued $32,850 in fines but apparently cleared the debt by serving 12 days in jail, after which she accrued a further $30,000 in fines. Interviews with the other two women, both in their early 40s and from Perth, showed that ‘they share care their children whenever one or the other goes to jail to “cut out” their fines’. One of the women [Jenny] spent three weeks in prison for fines of $18,000 for offences including driving without a licence and drink-driving. The Australian reported:

... she did try to complete 20 hours of community service instead, but failed after three days’ painting toys because of family problems that she says prevented her from attending ...‘In a way it’s OK because I don’t have that hanging over me now,’ Jenny said. ‘But I can’t get a job because of my record.’ (Taylor and Laurie 2015)

Under s 6A of the WA Regulations, converting fines to community work occurs at the rate of $300 for every six hours worked.[11] The offender must do ‘community corrections activities’ for a number of hours as specified in the WDO (s 50(1)(a) of the Act) and is required to work 12 hours per week until the fine is paid off (WA Regulations s 6A(2)). There is no legislative basis for, or Registrar practice of, concurrently serving fines by way of a WDO, unlike for imprisonment. With a $32,850 debt in the case of the first woman, she would need to work for 657 hours (or 109 days presuming a six-hour day) compared to the 12 days in jail. In relation to Jenny with $18,000 of debt, this would amount to 360 hours of work (60 days presuming a six-hour day). Adding the complications of finding childcare for each day, a three-week prison term may well be an ‘easier’ option. The Inspector’s finding that average lengths of imprisonment for fine default have dramatically fallen suggests this may be so. The Inspector found that, before the 2008 change to allow concurrent service of fines, the average length of prison term for fine default was 40 days whereas, after the change, this decreased to an average of 4.5 days (2016: 7 [3.6]) with 22 per cent of fine defaulters being received and released within 48 hours (2016: 8 [3.7]).

While the sample of women interviewed by The Australian is too small to draw any firm conclusions, it highlights how different components of the fines enforcement system may impact upon other areas of enforcement. We note, in particular here, that low conversion rates for fines under a WDO, uninspiring work, a more stringent policy for failing to attend community work, and potential difficulties with caring for children, may mean conversion via prison (particularly with the practice of serving fines concurrently) is a more appealing option. These cases also suggest there are some groups who are experiencing high levels of debt from fines together with recurring cycles of debt and enforcement action. This further underlines Brown’s (1987) point that simply abolishing imprisonment for fine default is not a satisfactory response to the complex issues raised by the heavy reliance on money penalties in contemporary justice systems.

Unlike WA, following the previously mentioned prison bashing of fine defaulter Jamie Partlic in 1987 and subsequent inquiry, imprisonment as a primary response to fine default was removed in NSW (Fines Act 1996 (NSW) (NSW Act) s 125). We would argue, however, that one of the most common enforcement mechanisms used against fine defaulters today in NSW[12] has a significant hidden punitiveness: namely, the usage of mandatory licence suspensions and cancellations. It is noteworthy that the Partlic bashing was the impetus for the Government introducing licence cancellations for unpaid fines to ‘replace the imprisonment of defaulters’ although, in its original conception, this was a principal sanction only against parking or traffic infringement default.[13] As Brown (1987) cautioned, it should not be accepted that any change from imprisonment for fine default is an improvement without understanding how those changes impact other areas. Given the importance of private motorised transport to so many facets of daily life, this default enforcement mechanism is highly punitive and may also be criminogenic in certain respects.

As with other fines legislation in Australia, the fines enforcement system in NSW is technical and complex. It is governed by the Fines Act 1996 (NSW) and the Fines Regulation 2015 (NSW) (the NSW Regulation). The enforcement system is largely administrative, not court-based or supervised (aside from some court fine enforcement orders). This is notwithstanding how consequential in various and differing ways many of these measures can be for those affected. These issues are compounded by the fact that most fines are generated by penalty notices which are administratively imposed in the first place and include mandatory penalties which take no account of individual circumstances, capacity to pay, and so on. Furthermore, unlike the WA enforcement system, the NSW system does not differentiate between court and penalty notice fines. Thus, to the extent that imprisonment is still a theoretical possibility in NSW, it is both administrative in character and available for fines not imposed by a court (and, indeed, for strictly civil debt like outstanding court costs).

The focus of this case study is on Road and Maritime Services (RMS) enforcement action by way of licence suspension/cancellation under Pt 4, Div 3 of the NSW Act.[14] In NSW, failing to pay a fine and continuing to default following the service of a penalty notice reminder, may lead to a penalty notice enforcement order being issued by the Commissioner of Fines Administration (the Commissioner)[15] (NSW Act, ss 40-45). Where default continues, this will result in the mandatory suspension of a driver’s licence (NSW Act, s 66). RMS must take this action and it is done without further notice to a fine defaulter (s 66(1)). The licence must be suspended even if a grant of extension of time to pay has been given by the Commissioner or an instalment plan arranged (s 66(1A)). Generally speaking, the licence is cancelled at the direction of the Commissioner, if the fine remains unpaid for more than six months (s 66(2)).

It should be noted that this mandatory enforcement mechanism occurs (unlike in its original conception) whether the default relates to a driving or parking offence or any other offence subject to a penalty or infringement notice. The NSW Legislative Assembly Committee (NSWLAC) inquiry into ‘Driver Licence Disqualification Reform’ (2013: 5 [2.17]) cited diverse offences leading to licence disqualification including failing to vote, not paying for a fishing licence, failing to wear a helmet, or travelling on a train without a ticket. In other words, driving sanctions are not related to driving behaviour or public safety on the roads, but simply to debt recovery. According to a report of the NSW Audit Office, driving sanctions are the most effective mode of enforcing fines (NSW Audit Office 2002). Yet, from the perspective of the purposes of punishment, there is no meaningful connection made between the original offence (and management of its associated risks) and the enforcement sanction used.

This enforcement mechanism impacts upon large numbers of persons. In the first half of 2016, 88,849 persons in NSW had their licences suspended for fine default (NSW RMS 2016). This exceeded the aggregate of suspensions and cancellations for all other reasons. Given the reliance upon driving by many people for employment and educational purposes, to access essential services, for entertainment including to see family and friends, and to undertake caring responsibilities, licence suspension/cancellation in and of itself is highly punitive.

The impacts on some communities are particularly harsh. The NSWLAC inquiry (2013: 10-17) found that vulnerable groups (economically and socially disadvantaged sectors of the community), those living in regional, rural and remote areas, Aboriginal communities and young people were most impacted. The NSWLRC inquiry (2012) on penalty notices found that:

... there are some Aboriginal communities in which there may be only one or two licensed drivers and that these drivers come under pressure to act as ‘taxi drivers’ to transport people to essential appointments. We also heard about the pressures on unlicensed people to drive unlawfully (for example to attend family funerals or to transport sick children). Grave concerns were expressed about the number of young Aboriginal men who are imprisoned for repeated ‘drive while disqualified’ offences, and about the consequent impact of imprisonment on them and their families. (NSWLRC 2012: 378 [16.5])

Close to a quarter of Indigenous appearances in NSW local courts are for motoring offences. The number of Indigenous people sentenced to imprisonment for driving while licence suspended or disqualified increased by 35 per cent in the first decade of the century. They constituted over a third of all people incarcerated for that offence (Beranger, Weatherburn and Moffat 2010: 3).[16]

Fines enforcement involves not only a form of ‘sentence creep’, in which a supposedly lenient penalty for a minor offence gives way to harsh sanctions for those who cannot pay, but is also criminogenic in its effects. As was said at the second reading of the Fines Further Amendment Bill 2008:

... the imposition of a fine or penalty notice on an already disadvantaged person simply opens the door to an excessive interaction with the criminal justice system. (Hatzistergos 2008)

One criminogenic effect is ‘secondary offending’.

Secondary offending in NSW typically occurs when a fine defaulter commits another offence related to enforcement action taken to recover the original outstanding fine. This may occur in three main ways. First, if a person has their licence suspended/cancelled due to fine default under s 66 of the Act and then drives during the period of suspension/cancellation, the driver commits the offence of driving while licence suspended or cancelled under the Road Transport Act 2013 (NSW) s 54(5).[17] Secondly, if RMS has cancelled the registration of a fine defaulter’s vehicle for failure to pay the fine (either under s 67(1) or at the Commissioner’s direction under s 67(2) of the Act) and the fine defaulter then drives that vehicle, the offence of using an unregistered vehicle on a road under s 68 of the Road Transport Act 2013 (NSW) is committed. Finally, while a person is not liable to be committed to prison for failure to pay a fine by the due date (NSW Act, s 125(1)), they are liable to be committed, in accordance with the Act, for failure to comply with a CSO (s 125(2)).

Our focus is on the first form of secondary offending: namely, offences for driving while the fine defaulter’s licence was suspended or cancelled (DWD). This is for three reasons. First, since 9 March 2009, there has been a separate offence of drive while licence is suspended/cancelled due to non-payment of fines under the Road Transport Act (NSW) s 54,[18] which enables us to track the number of such offences and convictions, and the penalties imposed for this particular offence. Until this legislative amendment commenced, the driving while suspended/cancelled offence in NSW did not differentiate based on whether it was due to fine default or otherwise (Hatzistergos 2008).[19] Secondly, there is no equivalent separate offence for using an unregistered vehicle on a road (s 68 of the Road Transport Act (NSW)), making it difficult, indeed, impossible to track this form of secondary offending. Finally, in relation to the third form of secondary offending, our inquiries (email correspondence with Richard Cant, Office of State Revenue, 17 February 2016) indicate that limited usage of CSOs has been made in recent years, with no CSOs issued prior to 2002, and the last issued in the 2009-10 financial year. Furthermore, the same correspondence indicated that no person has been imprisoned for breach of a CSO since 1996.[20]

Given the significant number of licence suspension/cancellations in NSW, secondary offending has the potential to affect a large number of persons. Furthermore, it has been suggested that this form of secondary offending is leading to fine defaulters being imprisoned in large numbers (see NSWLRC 2012: [8.29]; NSW Department of Attorney-General and Justice 2011: 47; see also the observations made by the NSW Aboriginal Legal Service cited in ALRC 2017a: 127 [6.78]). A study undertaken by the NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (BOCSAR) (Nelson 2015) for a one-year period (April 2013-March 2014) suggests otherwise. BOCSAR found that, out of the total sample of 8,874 DWD charges finalised in the NSW Local Court, a total of 505 people or 5.7 per cent were sentenced to imprisonment.[21] However, no people who had been found guilty of DWD due to fine default were sentenced to a term of imprisonment. This was despite the fact that a total of 214 people had at least one past DWD offence in the preceding five-year period. The main sentence issued was a fine (1,138)[22] with additional secondary penalties of licence disqualifications (1,136).

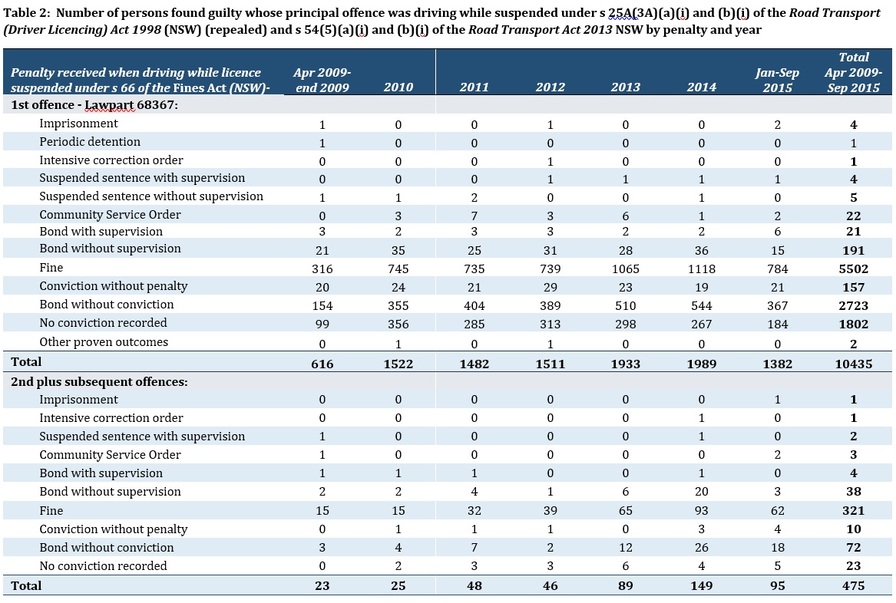

Given that the BOCSAR study was for only a one-year period, we wanted to determine if these trends were consistent across the full period since the operation of the new offence in 2009. We requested, therefore, data from BOCSAR for convictions in the NSW Local Court for offences of driving while suspended/licence cancelled from fine default, under both s 25A(3A) of the then Road Transport (Driver Licensing) Act 1998 (NSW) and the later s 54(5) of the Road Transport Act 2013 (NSW)[23] for the period of 9 March 2009 (being the commencement of s 25A(3A)) to September 2015, and for the penalties/sentences for these offences.[24]

From the more detailed statistics provided by BOCSAR we compiled Tables 1-5 (see Appendix 2). What these data show is that a staggering 10,934 persons were found guilty of DWD for fine default as the principal offence (Table 1). However, while concerns have been raised that this form of secondary offending is leading to the imprisonment of fine defaulters in large numbers, like the BOCSAR study, our research did not find this concern justified.[25] For the period April 2009 to September 2015, five people were convicted and sentenced to a term of imprisonment when their principal offence was DWD pursuant to non-payment of fines (see Table 1). Given that the number of people convicted of the offence in this period was 10,934, this renders the percentage of people entering the prison system negligible (0.046%). When combined with other quasi-custodial sentences,[26] the figure only increased to 44, or 0.4 per cent of those convicted (Table 4). What is clear, however, is that the majority of those convicted (53.41% or 5,840 persons) received an additional fine (Table 1).

In line with the BOCSAR study, our research demonstrates that the most common penalty imposed on these offenders is a further fine. While perhaps the concern to avoid sentencing such persons to incarceration has led to the fine being the most common sentencing option, it must be remembered that this means the court is imposing fines on those who have failed to pay their original fine and had their licence suspended/cancelled and still not been able to pay the fine and continued to drive whilst disqualified. Adding more financial debt to those who have failed to pay their original fine is clearly problematic and especially so if these people are from low socio-economic backgrounds.[27]

This problem is further accentuated if the DWD offence was committed by the offender in their endeavour to avoid further financial hardship, such as by working. For instance, the NSWLRC Report (2012: [8.26]) noted:

The suspension or cancellation of a driver license may hinder a fine recipient’s ability to keep his or her job, or to seek work, where possession of a valid license is essential. Thus license sanctions may aggravate the financial hardship that some people experience and which may be the main cause of their failure to pay the fine in the first place.

The Sentencing Council has reported that some people who cannot find alternative transport feel that they have to choose between breaking the law by driving without a valid licence, or losing their job or Centrelink payments (NSW Sentencing Council 2006: [5.36]-[5.38]). This dilemma is underscored with respect to those in rural communities (NSWLRC 2012: [8.28]).[28]

It should also be remembered that the offence of DWD s 54(5) had (until 28 October 2017) an associated additional mandatory period of licence disqualification (Road Transport Act 2013 (NSW) s 54(8)) being 3 months for a first offence and two years for a second or subsequent offence: s 54(9). These driving disqualification periods were also cumulative so that, where someone had accumulated more than one disqualification period, they would have to wait until they served the first disqualification period before they started serving the next one: s 54(8). The combined result was spiralling debt and lengthy disqualification periods, with the court having little discretion to avoid such effects, aside from imposing a s 10 non-conviction order: Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act 1999 (NSW) s 10.

A recent amendment to the Road Transport Act 2013 (NSW) by the Road Transport Amendment (Driver Licence Disqualification) Act 2017 (NSW) (which commenced operation on 28 October 2017) may reduce some of these problems. The Amending Act removes mandatory minimum licence disqualification periods for a variety of unauthorised driving offences, and introduces reduced ‘default’ periods and ‘minimum’ periods of disqualification, the latter being a period that the court may order if ‘it thinks fit’. For a first offence under s 54(5), the default period is three months, but the minimum period is only one month; and for a second or subsequent offence the default period is 12 months and the minimum period is three months: see now Road Transport Act 2013 (NSW) s 205A. The Amending Act also makes licence disqualification periods concurrent unless the court orders them to be cumulative: s 207A. Finally, the Amending Act reduces the maximum penalty for a second or subsequent offence under s 54(5) from two years imprisonment to six months. Disappointingly, however, given that the most common penalty for this offence is a fine, the penalty unit maximums remain unchanged.

While it is hoped that these amendments will have positive impacts, we would argue, as Brown (1987: 85) did, that we urgently need to have ‘an eye for the detail, a knowledge of the way the system currently operates’, including information about the background and financial capacity of fine defaulters to pay these additional penalties. We need mechanisms for knowing what happens to this group of offenders following these additional fines and licence disqualification periods being incurred, including knowledge of the lived experience of such enforcement mechanisms.

While it is beyond the scope of this article, we note that the NSWLAC inquiry heard from the NSW Legal Assistance Forum that it was not uncommon for Forum Members to assist clients with fine debt exceeding $10,000-15,000 (NSWLAC inquiry 2013: 18, [3.70]) in relation to licence sanctions from fine default. The NSW Ombudsman provided an example to the NSWLAC inquiry of an Aboriginal man who had $25,000 of fines which would have taken him 30 years to pay off on his time-to-pay plan (2013: 19, [3.71]). Case studies from the Homeless Persons’ Legal Service (2006) also suggest the significant impact of fine default, licence disqualification and DWD offences. For example, one case study involved a teenager, Ryan, who lived in a refuge and incurred significant railway and traffic fines. As he did not pay them back, his learner-driver’s licence was cancelled. The time-to pay arrangement he entered into meant that he would not have repaid his fines until he was in his 30s. ‘Not surprisingly, he gave up hope of getting a licence and started driving without one ... It did not take long to accumulate several years of court-imposed disqualifications’ (Homeless Persons’ Legal Service 2006: 10).

These examples illustrate the onerous hidden impacts that fines enforcement can have on some offenders, what amount to unfair and disproportionate hardships on the most vulnerable inflicted without appropriate safeguards or mechanisms of accountability. In March 2017, in part recognition of these problems, the NSW Act was amended (by the Fines Amendment Act 2017 (NSW)) to provide some flexibility to this mandatory system of licence disqualification. In s 65 (that is, ‘When enforcement action can be taken’ under Div 3) the ‘Note’ now provides that ‘civil enforcement action can be taken instead if the Commissioner is satisfied that civil enforcement action is preferable under s 71 [that is, when civil action can be taken]’. In the agreement in principle speech, the Minister for Finance, Services and Property stated this amendment is ‘particularly applicable to vulnerable members of the community or people living in rural or remote locations’ (Dominello 2017). It is too early to tell what impact this amendment will have, including what other impacts the turn to civil enforcement will have on such vulnerable groups. It is, however, pleasing to see that some flexibility in the system may result. We caution, though, that the NSW Act does not indicate how the Commissioner is to be so ‘satisfied’ that civil action is ‘preferable’, nor how a potential offender is able to prevent the mandatory licence suspension under s 66.

The final case study relates to a less common but, nevertheless, what we believe to be a punitive fines enforcement mechanism: the use of so-called ‘Name and Shame’ lists for fine defaulters. The first state to introduce this was Tasmania in 2008,[29] with WA following in 2013[30] and the Northern Territory (NT) in 2015.[31] While each regime is different, essentially, a legislative basis is provided in the relevant fines Act to publish the name of a fine defaulter on a publicly accessible government website following an enforcement order remaining unpaid after the 28 day notice period.[32] The NT legislation only allows publication if the unpaid fine exceeds $10,000;[33] the Tasmanian and WA schemes do not set minimum fine amounts for publication although the WA scheme appears to in practice.[34] The Tasmanian website is the most extreme, publishing not only the fine defaulters name/surname, suburb and the outstanding fine amount (as the WA and NT sites do) but also the full street address and residing state of the fine defaulter.[35] The Tasmanian site publishes details of fine defaulters who owe as little as $117.[36]

These registers are designed to stigmatise or shame fine defaulters into paying outstanding debts. These sites also impact upon large numbers of persons, particularly in Tasmania and the NT. There are currently 6,087 persons named on the Tasmanian site (at 1 September 2017), which is equivalent to just over one per cent of Tasmania’s population. The NT site currently lists 560 persons.[37] There are 100 published on the WA site, being the top 100 fine defaulters.

This form of enforcing fines works through a different logic to the classic understanding of the fine as designed to ‘cool’, de-dramatise and drain punishment of its emotional and cultural meanings as described in Part 1. Instead, it exploits classic ‘law and order’ (Hogg and Brown 1998) punitive popular sentiments, naming, shaming and stigmatising the fine defaulter. This ‘re-individualises’ the offender and restores the element of spectacle to the penalty. Members of the public can access personal details of fine defaulters (including full address on the Tasmanian website). The fine defaulter may be further stigmatised by the media. In each jurisdiction where such a scheme operates, it is common practice for journalists to run annual stories about the ‘top’ fine defaulters, including naming them and their fines history (for example, see Burgess 2014 (Tas); Dunlop 2017 (NT); Hickey 2013 (WA)).

Clearly the privacy invasion[38] and stigmatising nature of these schemes may also result in significant consequences for the fine defaulter. The Tasmania website indicates that:

If your name appears in the published list, this could have implications on your

• credit rating;

• ability to secure credit;

• renting property; or

• otherwise secure finance.

You should take immediate action to resolve your monetary penalties.

We would add, given the public nature of the websites, it could damage fine defaulters’ employment or prospects of employment, potentially further adding to the financial difficulties of the fine defaulter.

There is no doubt that the attractions of the fine as a penalty are real, certainly where the alternative might be imprisonment or involve some other intrusive form of supervision (see the debate on the role of the fine in the USA in a special issue of Criminology and Public Policy 2011). Nevertheless, this should not blind us to the hidden and unfairly punitive consequences of fines for a sizeable minority. In addition to the very real but often hidden hardships inflicted on the most vulnerable by fines and by current enforcement arrangements, it is also of note that efforts to address endemic enforcement problems are seeing the reappearance of other penal styles and strategies via the backdoor of administrative process: for example, a form of penal-welfarism in the case of Work and Development Orders in NSW and Queensland and naming and shaming measures in the NT, WA and Tasmania. The fine, in its apparent simplicity, transparency and familiarity, hides complex penal and social realities and effects that are deserving of far greater attention than they have yet received.

As American anthropologist David Graeber observes in his history of debt, it is the ‘very apparent self-evidence’ of the statement that ‘one has to pay one’s debts’ that makes it so ‘insidious ... the kind of line that could make terrible things appear utterly bland and unremarkable ...’ (Graeber 2012: 4). The danger with the growing monetisation of punishment, the reduction of justice to an economic transaction that is precisely quantifiable, a debt that is ‘simple, cold, and impersonal’ (the qualities that make fines so attractive), is that consideration of ‘needs, wants’, ‘human effects’ are more readily dispensed with (Graeber 2012: 13).

With the abolition of imprisonment for fine default, public interest in the manifold human and social consequences of widespread reliance on fines seems to dissipate. The historical links between debt and servitude are forgotten. In the past, debt was commonly used as an instrument for driving people into literal servility—debt peonage—and there are latter day equivalents that bear closer scrutiny.

Today, fine defaulters are still finding their way into prison, if by a more circuitous and less visible route. For others, criminal justice debt can indeed amount to a modern-day form of servility, hanging over and constraining people’s lives for years on end, as examples cited above indicate. No matter the time it takes or the costs it imposes, it seems, we must all pay our debts.

But, in all manner of ways, inside and outside the justice system, as Graeber points out, ‘the principle has been exposed as a flagrant lie. As it turns out, we don’t “all” have to pay our debts. Only some of us do’ (2012: 391). The criminal justice system doesn’t even insist that all offenders pay their debts, as long as they are paid by someone. This privileges those like large corporations that can simply factor the cost into pricing or transfer it in other ways. Elsewhere, as we see with banks and other large corporations, with tax evasion by the wealthy and other white-collar crimes involving vast financial sums, wrongdoers (when they fail to wholly escape sanction) generally manage to negotiate mutually agreeable settlements away from the moral gaze of the criminal justice system and sheltered from the ‘sacred principle’ requiring the honouring of all debts.

Correspondence: Julia Quilter, Associate Professor, School of Law, University of Wollongong, Northfields Avenue, Wollongong NSW 2522, Australia. Email: jquilter@uow.edu.au

Ashworth A (2005) Sentencing and Criminal Justice, 4th edn. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Audit Office of NSW (2002) State Debt Recovery Office: Performance Audit Report, Collecting Outstanding Fines and Penalties. Sydney: Audit Office of NSW.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (2017) Criminal Courts, Australia, 2015-16, Cat. No. 4513.0.Available at http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/allprimarymainfeatures/50C00231EA88E8E6CA2582410016F9B5?opendocument (accessed 11 April 2018).

Australian Law Reform Commission (ALRC) (2017a) Pathways to Justice: An Inquiry into the Incarceration Rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. Discussion Paper 84. Canberra: ALRC.

Australian Law Reform Commission (ALRC) (2017b) Pathways to Justice: An Inquiry into the Incarceration Rates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People. Final Report 133. Sydney.

Baird B (1987) Second reading speech, Motor Traffic (Penalty Defaults) Amendment Bill; Justice (Penalty Defaults) Amendment Bill; and Transport (Penalty Defaults) Amendment Bill. Hansard, Legislative Assembly, NSW Parliament, 23 November: 17025-17039.

Beckett K and Harris A (2011) On cash and convictions: Monetary sanctions as misguided policy. Criminology and Public Policy 10(3): 505-537.

Bentham J (1843) Principles of penal law. In Bentham J (under the superintendence of his executor, John Bowring (ed.)) The Works of Jeremy Bentham, published, Vol. 1 of 11: 1838-1843. Available at http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/2009#Bentham_0872-01_3776 (accessed 11 April 2018).

Beranger B, Weatherburn D and Moffat S (2010) Reducing Indigenous contact with the court system. Crime and Justice Statistics Bureau Brief: Issues Paper No 54. Sydney: BOCSAR.

Bottoms A (1983) Some neglected features of contemporary penal systems. In Garland D and Young P (eds) The Power to Punish: Contemporary Penality and Social Analysis: 166-202. London: Heinemann.

Brown D (1987) Imprisonment for fine default (NSW) revisited. Legal Service Bulletin 12(2): 84-85.

Brown M, Lansdell G, Saunders B and Eriksson A (2013) I’m sorry but you’re just not that special...’ Reflecting on the ‘Special Circumstances’ Provisions of the Infringement Act 2006 (Vic). Current Issues in Criminal Justice 24(3): 375-393.

Brull M (2016) The death Of Ms Dhu: The unheard screams, and what they show about police racism. New Matilda, 21 December. Available at https://newmatilda.com/2016/12/21/the-death-of-ms-dhu-the-unheard-screams-and-what-they-show-about-police-racism/

Burgess G (2014) 3000 named for unpaid fines. The Examiner, 15 June. http://www.examiner.com.au/story/2353117/3000-named-for-unpaid-fines/

Carlen P and Cook D (eds) (1989) Paying for Crime. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

Criminology and Public Policy (2011) Special issue on monetary sanctions as misguided policy 10(3): 483-837.

Dominello V (2017) Minister for Finances, Services and Property, 2nd Reading Speech on Fines Amendment Bill 2017, Hansard, Legislative Assembly, NSW Parliament, 14 February 2017: 47 (proof).

Donnelly N, Poynton S and Weatherburn D (2016) Willingness to pay a fine. Crime and Justice Bulletin Number 195. Sydney, New South Wales: NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research.

Dunlop C (2017) The Northern Territory’s biggest fine dodgers exposed. NT News, 4 June http://www.ntnews.com.au/news/northern-territory/the-northern-territorys-biggest-fine-dodgers-exposed/news-story/7026e098fbee37d81dfee0424c6e7516

Elliott and Shanahan Research (2008) An Investigation of Aboriginal Driver Licensing Issues. Sydney: Roads and Traffic Authority of NSW.

Faraldo-Cabana P (2014) Towards equalisation of the impact of the penal fine: Why wealth of the offender was taken into account. International Journal of Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 3(1): 3-15. DOI: 10.5204/ijcjsd.v3i1.143.

Faraldo-Cabana P (2017) Money and the Governance of Punishment: A Genealogy of the Penal Fine. London: Routledge.

First Nations Deaths in Custody Watch Committee Inc (2017) Justice for Miss Dhu. Available at http://www.deathsincustody.org.au/dhucampaign (accessed 22 March 2018).

Fox R (1995a) Infringement notices: Time for reform? Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice 50. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology.

Fox R (1995b) Criminal justice on the spot infringement penalties in Victoria. Australian Studies in Law, Crime and Justice. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology.

Fox R (1999) Criminal sanctions at the other end. Paper presented at the 3rd National Outlook Symposium on Crime in Australia: 22-23 March. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory: Australian Institute of Criminology.

Freiberg A and Ross S (1999) Sentencing Reform and Penal Change: The Victorian Experience. Leichhardt, New South Wales: Federation Press.

Garland D (2001) The Culture of Control. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Garton S (1982) Bad or mad? Developments in incarceration in NSW 1880-1920. In Sydney Labour History Group (eds) What Rough Beast? The State and Social Order in Australian History: 89-110. Sydney, New South Wales: George Allen and Unwin.

Graeber D (2012) Debt: The First 5,000 Years. New York: Melville House.

Harris A (2016) A Pound of Flesh: Monetary Sanctions as Punishment for the Poor. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Harris A, Evans H and Beckett K (2010) Drawing blood from stones: Legal debt and social inequality in the contemporary United States. American Journal of Sociology 115(6): 1753-1799.

Hatzistergos J (2008) (Minister for Justice) Second reading speech, Fines Further Amendment Bill 2008. Hansard, Legislative Council, NSW Parliament, 27 November: 11968-11973.