|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy |

James Heydon[1]

University of Lincoln, United Kingdom

|

Abstract

Procedural environmental justice refers to fairness in processes of

decision-making. It recognises that environmental victimisation,

while an

injustice in and of itself, is usually underpinned by unjust deliberation

procedures. Although green criminology tends to

focus on the

former—distributional dimension of environmental justice—this

article draws attention to its procedural

counterpart. In doing so, it

demonstrates how the notions of justice-as-recognition and

justice-as-participation are jointly manifested

within its conceptual

boundaries. This is done by using the consultation process that occurs with

indigenous peoples on proposed

oil sands projects in Northern Alberta, Canada,

as a case study. Drawing from ‘elite’ interviews, the article

illustrates

how indigenous voices have been marginalised and their Treaty rights

misrecognised within this consultation process. As such, in

seeking to

understand the procedural determinants of distributional injustice, the article

aims to encourage broader green criminological

scholarship to do the same.

Keywords

Green criminology; environmental justice; oil sands; First Nations; Treaty

rights.

|

Please cite this article as:

Heydon J (2018) Sensitising green criminology to procedural environmental justice: A case study of First Nation consultation in the Canadian oil sands. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 7(4): 67-82. DOI: 10.5204/ijcjsd.v7i4.936.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence. As an open access journal, articles are free to use, with proper attribution. ISSN: 2202-8005

Procedural environmental justice refers to fairness in processes of decision-making. Recognising the difficulties involved in unilaterally specifying fairness in outcomes in relation to environmental issues, this form of justice advocates widespread democratisation of deliberation procedures.

The purpose of this article is to explore how justice-as-recognition and justice-as-participation are jointly manifested within the concept of procedural environmental justice. In using this to examine the process of First Nation consultation in the Canadian Oil Sands, the article also demonstrates how the conception translates into concrete application. The impetus for this is twofold. First, while green criminologists have ‘devoted most of their attention to illuminating and describing different types of environmental harm’ (Brisman 2014: 2, emphasis in original), it is not enough to focus on consequences alone if an explanation for victimisation is being sought. Instead, this requires an understanding of ‘who has the power to make decisions, the kinds of decisions that are made, in whose interests they are made, and how social practices based on these decisions are materially organised’ (White 2008: 56). The challenge, therefore, is to identify the procedural determinants of environmental harm and examine the reasons for their victimogenic operation.

Second, existing explanations for ecological disorganisation in the Canadian Oil Sands prioritise macro level analyses. Harm is explained by the expansionary tendencies of global capitalism (Lynch, Long and Stretesky 2016), the predatory influences of the North American Free Trade Agreement (Smandych and Kueneman 2010), or contemporary structures inherent to the Canadian settler-colonial state (Huseman and Short 2012). While insightful, these accounts focus primarily on international and national political and economic pressures, suggesting that overarching state and corporate power proceeds uninhibited on its way to unilaterally industrialising the oil sands resource. This disguises the central role of provincial government apparatus in sanctioning extractives activity and obscures repeated attempts by local indigenous peoples, or First Nations, to oppose it through the regulatory consultation process. As a result, there is very little information on how constitutionally protected Treaty rights of First Nations—to hunt, fish and trap on the land and be consulted on any activity that may adversely affect their ability to do so—have been circumvented in the process of sanctioning oil sands expansion. Here, this shortcoming is addressed.

This article is in four sections. The first outlines procedural environmental justice as a concept. It does this by highlighting the limits inherent to the dominant, distributive-focused conception used within green criminology for over two decades. This includes discussion of how justice-as-recognition and justice-as-participation can complement, not replace, this concept and provide an approach for evaluating decision-making processes underpinning distributional injustice. The second section presents an overview of the oil sands and First Nation Treaty rights, followed by an explanation of how they manifest within the regulatory process governing oil sands expansion. The third section outlines the methods, findings and analysis of interview data, with a specific focus on aspects of consultation towards which participants directed criticism. In the final section, the article discusses the findings in the context of procedural environmental justice, illustrating how the recursive relationship between institutionalised marginalisation and misrecognition acts to produce distributional injustice for First Nations.

Over a decade ago, Zilney et al. (2006: 47) highlighted the ‘dearth of criminological attention’ being directed at issues of environmental justice. Almost ten years later, a review of the green criminological literature described its contribution to environmental justice research as ‘modest at best’ (Lynch, Stretesky and Long 2015: 5). Effort has been made to redirect green criminological study towards under-acknowledged aspects of environmental justice, including its ties to social justice (Davies 2017), ecology (White 2007), and political economy and social movements (Lynch et al. 2015). However, for the most part, the sub-field has relied on a conception that focuses almost entirely on unequal distributions of harm along the lines of gender, class and ethnicity. This is evidenced by empirical work conducted by a relatively small group of scholars. These have explored the intersection of socio-economic conditions and environmental hazards among American indigenous communities (Lynch and Stretesky 2012), pesticide exposure experienced by migrant workers in relation to the citing of waste-to-energy facilities (Lynch and Stretesky 1998), the proximity of public schools to environmental hazards (Stretesky and Lynch 2002), and the relationships between relatively poor, minority communities and the situating of coal-fired power stations (Kosmicki and Long 2016). Ultimately, the overwhelming concern has been on distributional injustice. This stems from three consecutive decades of criminological thought, which has conceived of environmental justice almost uniformly as:

[T]he geographical association between race, ethnicity, economic indicators, and areas that contain hazardous substances... . (Stretesky and Hogan 1998: 269)

[T]he distribution of environments among peoples in terms of access to and use of specific natural resources in defined geographical areas, and the impacts of particular social hazards and environmental hazards on specific populations (e.g. as defined on the basis of class, occupation, gender, age, ethnicity). (White 2007: 37)

[T]he unequal distribution of pollution and variability in the social control of pollution across communities with varying racial, ethnic and class compositions. (Lynch et al. 2015: 2)

Although giving priority to the ‘fundamental question’ of all justice theory (Brighouse 2004: 2) and illustrating the scale and scope of environmental issues at hand, purely distributive paradigms such as this ‘tend to ignore the institutional contexts that influence or determine the distributions’ (Schrader-Frachette 2002: 27). This cannot be said to characterise the sub-field as a whole, however, as much green criminological work does focus on drawing out these influences. For instance, deficits in democracy have been found to contribute to socio-environmental conflict over mining in Argentina (Weinstock 2017), while the commercialisation of nature across Latin America is facilitated by a web of legal and illegal injustices (Goyes and South 2017). Similarly, the absence of citizen participation in decision-making is implicated in long-standing, violent conflicts over land use in Colombia (Goyes and South 2016). Various aspects of procedural injustice are clearly recognisable in such accounts, but as the concept is not deployed as a specific lens through which to conduct analysis its conceptual contours are only ever implied. Consequently, despite its presence throughout green criminological literature, the concept of procedural environmental justice has rarely been subject to direct theoretical development or empirical exploration.

An exception to this can be found in White (2013), where environmental justice is described as multi-dimensional. This ‘trivalent’ conceptualisation is more prevalent outside of green criminology, where the literature has long incorporated the concepts of justice-as-recognition and procedural justice alongside that of distribution (Walker 2012). Although conceptually distinct, the integration of this trio acknowledges that unequal exposure to environmental harm tends to stem from unequal access to decision-making processes. This is why, in reality, the relationship between the three forms of justice are ‘played out in the procedural realm’ (Schlosberg 2007: 26). Patterns of injustice-as-equity and injustice-as-misrecognition both impede participation and vice versa, meaning that the procedural dimension gains priority as the space in which distributional justice is either ensured or inhibited. It is in this context that specific qualities of recognition and participation can be distilled to permit an assessment of procedural environmental justice.

The notion of procedural justice can be defined as the ‘fair and equitable institutional processes of a state’ (Schlosberg 2007: 25). These may encompass state practices in relation to law and regulation or, given the decentralisation of state functions under neoliberalism, implicate institutional settings and actors from the private or third sectors (see Walker 2012). Whichever is under examination, procedural justice recognises that a deliberation process may be conceived as unfair in and of itself, irrespective of the distributive inequities that may result. Having roots in the literature on public engagement, the operational features of this dimension can be traced back to Arnstein’s (1969) pioneering ‘ladder of citizen participation’. Referring to a spectrum of participatory categories, these range from ‘non-participation’, where people are effectively excluded from the decision-making process, through to ‘citizen power’, where members of the public exert some control over the decisions made. For Arnstein (1969: 216), facilitating these latter stages of engagement is key because they represent a fairer process:

[P]articipation without redistribution of power is an empty and frustrating process for the powerless. It allows the power-holders to claim that all sides were considered, but makes it possible for only some of those sides to benefit.

Subsequent conceptions have modified Arnstein’s ladder in various ways, moving from Dorcey et al.’s (1994) ladder of ‘informing’ to ‘ongoing involvement’, through Silverman’s (2005: 37) continuum between ‘grassroots’ participation and ‘instrumental’ engagement, and on to Tritter and McCallum’s (2006) multiple ladders model. Yet, irrespective of their variances, all maintain an emphasis on facilitating meaningful, or influential, citizen engagement in decision-making at multiple stages. Accordingly, for participation within a procedure to be deemed just, all participants should have the opportunity to be listened to and to be heard, to have their contributions respected, valued and considered, and to have a chance to determine the scope of issues to be reviewed (George and Reed 2017). This latter aspect is particularly important as it addresses the question of which environmental problems are to be produced in the first place.

The notion of justice-as-recognition intersects substantially with its procedural counterpart, largely because ‘if you are not recognized, you do not participate; if you do not participate, you are not recognized’ (Schlosberg 2007: 26). Rooted in Fraser’s (1996; see also Young 1990) broadly applicable concept of ‘participatory parity’, justice-as-recognition requires individuals within a group to be considered full members in a social interaction. Under this conception, un-, mis- or mal-recognition may take the form of ‘cultural domination’, of being forced to adhere to the culture of another, ‘non-recognition’, which is akin to being rendered invisible, or ‘disrespect’, which refers to routine disparagement (Fraser 1999: 32). These are unjust in and of themselves because they serve to devalue and demean by preventing individuals from being treated on par with others in society. In this sense, if applying the concept to decision-making processes, the standards to be attained are inclusivity, respectfulness and equality (see Hunold and Young 1998; Schrader-Frachette 2002). The exact manifestation of these may differ by institution, but participation should involve access for a diversity of stakeholders at different stages of deliberation, transparent and accountable communication structures, and special consideration or accommodation for adversely affected and previously marginalised groups (George and Reed 2017).

Conceiving of procedural environmental justice in this way, as a site in which questions of justice-as-recognition and justice-as-participation converge, draws attention to the ways in which prior injustices contribute to inequitable distributions of harm. It also provides a more ‘complete’ framework for analysis when compared to the relatively one-dimensional conception dominating green criminological scholarship (Schlosberg 2007: 40). To demonstrate how this can be applied in reality, the article now turns to the consultation process that occurs with First Nations on prospective extraction projects in the Canadian Oil Sands.

Following confederation in 1867, the Government of Canada signed 11 Numbered Treaties with various indigenous peoples across the breadth of Canada’s landmass. These were the primary means through which title to substantial tracts of indigenous land were exchanged for formally acknowledged ‘reserve’ areas, hunting, fishing and trapping rights, and guarantees that indigenous peoples would adhere to Crown laws and customs. Such imperatives underpinned the signing of Treaty 8 in 1899, which covers most of the oil sands deposit in Northern Alberta. With the energy potential of bitumen largely unrecognised at this point, the over-riding purpose of Treaty 8 was to extinguish Aboriginal Title to 840,000 square kilometres of land in order to open up the area for settlement, mining and passage northwards after gold was found in the Yukon (Fumoleau 2004).

The ancestors of present-day First Nations would not agree to the terms of Treaty 8 unless their hunting, fishing and trapping practices were protected on said ‘surrendered’ land. As Sifton (quoted in Government of Canada 1899) made clear in the Report of Commissioners for Treaty No. 8, ‘we had to solemnly assure them that ... they would be as free to hunt and fish after the treaty as they would be if they never entered into it’. Yet, accompanying these promises was a ‘lands taken up provision’ where, in exchange for these protections, the Government of Canada (1899) would receive permission to take up tracts of indigenous territory ‘from time to time for settlement, mining, lumbering, trading or other purposes’. Leaving aside lingering questions about the legitimacy of the ‘surrendering’ interpretation (see Huseman and Short 2012), this agreement established the legal, political and regulatory basis for the future development of the oil sands resource within the boundaries of Treaty 8.

Rapid expansion of the oil sands industry began in the mid-1990s, when rising global prices for conventional oil made extraction of the resource more attractive to investors (Chastko 2007). Since then, industrial contamination and encroachment onto Treaty territory has reduced the quantity and quality of resources needed by First Nations to continue their traditional land-based activities of hunting, fishing and trapping on the land. This has resulted in a form of environmental victimisation known as ‘cultural loss’ (Heydon, forthcoming) or, if also accounting for the institutional structures of settler-colonialism, ‘cultural genocide’ (Huseman and Short 2012). Stemming from recognition that the natural environment is central to the collective identities of indigenous peoples (see Castree 2004), these terms point to those occasions in which this relationship has been degraded or severed. In the case of the oil sands, they refer to a form of alienation from environment that not only impedes the ability to engage in activities underpinning traditional land-based culture but one which also undermines those more immaterial aspects of collective identity that physical expression helps to reproduce (see Heydon, forthcoming).

While such experiences have elicited different intensities of indigenous opposition both within and between communities as attempts are made to reach a compromise between land preservation and the need to attract capital investment into their communities (see Taylor and Friedel 2010), the concerns that are expressed tend to focus on the detrimental impact of extraction on the hunting, fishing and trapping practices protected by Treaty rights. Yet, despite this, there was no legal requirement for government to consult with First Nations on proposed extractive projects until 2005, by which point oil sands production had increased by almost 300 per cent, from 55 million barrels per year in 1995 to 160 million (Government of Alberta 2018). During this period, First Nations were only included in a much narrower stakeholder engagement processes as ‘directly and adversely affected’ persons. This means that, for much of the period in which interest in extraction of the oil sands has existed, First Nations have had little say in where the industry should expand, at what pace and if it should do so at all.

This situation changed in 2005 when oil sands projects within the remit of a Treaty area could no longer be approved before the proponent had consulted with First Nations. Known as the ‘duty to consult and accommodate’, this requirement emerged from two judgments issued by the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) in the mid-2000s: Haida Nation v. British Columbia (Minister of Forests) [2004] 3 SCR 511 (hereafter Haida); and Mikisew Cree First Nation v. Canada (Minister of Canadian Heritage) [2005] 3 SCR 388 (hereafter Mikisew). The latter is most immediately relevant to the oil sands as it extended the duty to a Treaty context. In this case, the Crown had intended to build a winter road through a First Nation reserve, with the plan being informed by public comment only and not specific consultation with the First Nation. Referring directly to the text of Treaty 8 and acknowledging that surrendered lands ‘from time to time’ could be ‘taken up’ for various purposes by the state, the SCC noted the absence of detail by which this process is supposed to occur. Deciding that ‘the Crown was and is expected to manage the change honourably’ (Mikisew para. 31), the SCC filled this procedural gap with the duty to consult and accommodate. Triggered when a plan of action risks adversely affecting a substantive Treaty right, like the ability to hunt, fish or trap on the land, the obligation to act ‘honourably’ requires the government to conduct an iterative process of consultation with the intention of accommodating First Nation concerns by altering the original plans accordingly. While this ‘does not give Aboriginal groups a veto over what can be done with the land’ (Haida para. 48), ‘consultation that excludes from the outset any form of accommodation would be meaningless’ (Mikisew para. 54).

This case study is part of a larger piece of research investigating the criminogenic potential of ‘sustainable development’ in oil sands policy and practice since the mid-1990s. The data presented here are drawn from an analysis of 33 semi-structured interviews with senior personnel involved in the process of First Nation consultation. This was collected in 2015 at relevant locations in Alberta, including Calgary, Edmonton and Fort McMurray.

Given the difficulties involved in accessing powerful institutions (see Williams 2012) and the need to gather information from networks of actors with specific knowledge of the consultation process, a six month period of ‘relational groundwork’ (Adler and Adler 2002: 526) was undertaken prior to the interviews in order to gain access. Once in the field, chain-referral sampling was used to locate other appropriate participants (see Penrod et al. 2003). This ensured a close alignment between the interview sample and the research questions, which focused on tensions within the consultation process. Widely used in ‘up-system’ research, this method excels at ‘identifying policy-makers and specific elites, and understanding networks and processes’ (Williams 2012: 17). The interview transcripts were subject to the specific stages of thematic analysis outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006). This was conducted in tandem with the data collection, allowing sampling to continue until no new or deviating data was being added to the codes and categories of analysis, thereby ensuring its credibility. This is a standard akin to theoretical saturation, but without the framework of grounded theory (see Saunders et al. 2017).

Participants included senior members of the Energy Resources Conservation Board (ERCB), Land Use Secretariat (LUS), Alberta Energy Regulator (AER) and Aboriginal Consultation Office (ACO). The first two of these agencies have more recently been consolidated under the ACO and are included here because the research was conducted during the transition period. Participants from the oil sands industry (Industry) were also included, as were members from two First Nation Industry Relations Departments (FNIRD) local to the industry. This latter group was integral to the consultation process, acting as the link between their communities, government and industry. For the purposes of definition, the term ‘First Nations’ here refers to indigenous groups that are signatories to Treaty No. 8 of 1899.

Those interviewed spoke of three aspects of consultation acting to undermine First Nation participation: the early disposition of land leases; the delegation of consultation to industry proponents; and the premature determination of consultation ‘adequacy’ by the ACO. Accompanying these issues were broader criticisms directed at features of policy that exert influence within the operational process of consultation. These include government use of a dematerialised concept of Treaty rights, a Land Use Plan that excluded First Nation input on conservation areas, and two consultation policies that were finalised without inclusion of First Nation input. Each of these are taken in turn.

The disposition of land leases is the first stage in the regulatory process governing individual project approvals. This was also the earliest point at which First Nations directed criticism, noting that government agencies dispose of these leases without consulting on their potential impact to Treaty rights beforehand. This was reiterated by Participant B from the LUS, who also clarified the rationale behind Alberta’s approach:

In some jurisdictions in Canada, at the issuance of a lease stage, there’s actually consultation with a First Nation ... because in their mind that’s the watermark for when the land becomes taken up. We say no, we’re not going to consult at the lease phase because the company might walk away from the lease, they might not actually do anything with the land; we’re not sure it’s taken up until the company proposes an activity. (Participant B, LUS)

This position recognises that the conversion of land ‘parcels’ into ‘producing leases’ is not automatic, and that subsequent development largely depends on the success of exploration following the purchase. However, it also obscures the extent to which the land disposition process encourages oil sands development from the offset, a characteristic visible in guidelines governing the process by which industry actors obtain leases. For instance, Section 4 of the Oil Sands Tenure Regulation recognises an ‘oil sands agreement’ to ‘convey the exclusive right to drill for, win, work, recover and remove oil sands that are the property of the Crown’ (Government of Alberta 2010: 11), meaning there is little question as to the intent of the lease mechanism. Erring on the side of non-development of a land lease—as the interpretation maintained by regulatory personnel does—also ignores the requirement for purchased parcels to meet the Minimum Level of Evaluation outlined in Section 2 of the Oil Sands Tenure Regulation. This requires ‘the drilling of at least one evaluation well’ prior to seismic testing (Government of Alberta 2010: 7-9). The lease disposition mechanism therefore contains within it a high likelihood that lands will be changed from a category where Treaty rights apply to one where they do not (see Mikisew para. 30), particularly if compared to the reduced likelihood of conversion prior to disposition.

The First Nation participants were particularly critical of this aspect of consultation, arguing that it does not correspond to the decisions handed down by the SCC. This appears to be correct. While the Haida (para. 35) judgment suggests that the duty to consult is triggered by evidence pertaining to the risk of an adverse effect on Treaty rights, the Mikisew (para. 56) judgment contains no such requirement for proof of a potential consequence. If taking the stricter Haida judgment as the starting point, consultation is only triggered ‘when the Crown has knowledge, real or constructive, of the potential existence of the Aboriginal right or title and contemplates conduct that might adversely affect it’ (Haida para. 35, emphasis added). The duty is therefore not triggered by an actual impact on the substantive component of Treaty rights, but a possible impact. In light of this, consultation should still occur at the point of disposition because regulations governing the process are weighted in favour of activities clearly posing such a risk. Alternatively, if operating on the basis of the Mikisew (para. 56) judgment, the possibility of an impact is not even required. The Crown’s right to take up lands under treaty ‘is subject to its duty to consult and, if appropriate, accommodate First Nations’ interests before reducing the area over which their members may continue to pursue their hunting, fishing and trapping rights’. As such, while the granting of a lease does not in itself constitute a process by which land is rendered incompatible with Treaty rights, it can be read as the beginning of the process by which land is altered in this manner. Consequently, the First Nations’ argument is supported by the text of either the Haida or Mikisew judgments: consultation should be triggered at the point of lease disposition.

Following the process of granting land leases, First Nation concerns centred on the delegation of consultation responsibility to industry proponents. A key contention maintained by First Nations is with regard to the cumulative environmental impact of oil sands development on the exercise of their Treaty rights. With the Crown passing the majority of initial consultation responsibilities to industry prior to project approval, justifications for this delegation were based on the purported expertise held by companies themselves. As one government participant noted, ‘[a] lot is delegated to industry because in order to mitigate impacts they’re in the best position to do so’ (Participant C, ACO). Participants from industry agreed, adding that ‘companies are doing all the legwork ... that’s accurate, for sure’ (Participant A, Industry). However, the point at which this consultation mechanism encounters the concerns held by First Nations produces an obvious and systemic tension:

First Nations cannot broach issues to do with cumulative effects at the point of consultation with industry, and government delegates all of that to industry. They can only do it, and deal with issues like project emissions, on a project-by-project basis. (Participant A, FNIRD 1)

With consultation delegated to individual companies and its scope restricted to considering the environmental effects of individual projects, the process has difficulty including issues beyond this narrow focus. As such, the very first point at which industry is required to consult with First Nations exposes a markedly limited capacity to address and accommodate one of their key environmental concerns: the collective impact of projects on the surrounding ecosystem. This is exacerbated by a ‘nuance’ referred to by Participant B of the LUS; that First Nations are not simply concerned about cumulative environmental effects, but about how such effects may impact the exercise of specific Treaty rights. It therefore follows that not only are individual companies unable to view even the first stage of harm—the cumulative ecological disorganisation—they are also blind to the Treaty impacts that result from its materialisation. Speaking of those instances where concerns surrounding cumulative effects are raised with proponents, Participant A from Industry explained that, in business, ‘[a] lot of the time it’s described as a provincial matter’. This was made in reference to the lack of both capacity and perceived responsibility for industry to address such concerns.

Before an oil sands project can move onto the next stage of the regulatory process, proponent consultation has to be deemed adequate by the ACO. As such, this agency also drew criticism from First Nations who considered it to ‘only work at industry’s side’, arguing that ‘[t]hey basically see consultation as information, or giving information to First Nations and receiving some in return. Consultation is a minimal process’ (Participant B, FNIRD 1). The First Nations characterised the ACO as ‘very administrative’, setting out ‘a process which is flawed, and which has systematic discrimination, where you can never actually demonstrate impact’ (Participant A, FNIRD 2). This criticism was tied to the provincial government’s narrow interpretation of Treaty rights. Outlined in its 2005 and 2013 policies on consultation (see Government of Alberta 2005, 2013), this underpins the ACO’s minimum standard of consultation by setting out the content of said rights in light of SCC judgments. The basic divergence of FNIRD and government views was summarised by Participant C within the ACO, where ‘First Nations believe Treaty rights is to a broad suite of things, whereas Alberta believes the right only extends to hunt, fish and trap for food’. However, Participant A from FNIRD 2 expanded on this, describing how, beyond the food restriction, the lack of policy detail provides a space in which the ACO can operationalise an even narrower interpretation:

Alberta states that the Aboriginal and Treaty rights to fish, hunt and trap is not pegged to any site-specific location. So it’s more about the right to hunt as opposed to the right to hunt on that little plot over there ... or the plot across the river. Those are not protected, but it’s about your ability and right to do it somewhere out on the landscape. And recently I got a letter from the Aboriginal Consultation Office that reaffirmed also that not only is it not site-specific, but your right to hunt is not species-specific. And so a good question would be, what does that mean? Because they’ve not actually said that in writing before. What that would mean to me is that Alberta is looking at protecting First Nations’ rights to hunt, fish and trap on the landscape, but not guarantee any specific location, and not guaranteeing that there’ll be a certain species or abundance of a certain quality in a certain area. So that, of course, is a direct opposite interpretation about how First Nations view it, because ... our interpretation of Aboriginal Treaty rights are to all parts of the land ... So that interpretation is really at the opposite ends of the scale of how you look at what a [Treaty] right is.

In restricting Treaty rights to subsistence practices, and divorcing them from the material quantity and quality of resources underpinning their execution, the ACO is operationalising a diluted conception that is at odds with SCC judgments. Interpreting Treaty rights to hunt, fish and trap on the land as only for food does not accord with Mikisew, which states that hunting, fishing and trapping practices ‘cannot be isolated from the Treaty as a whole, but must be read in the context of its underlying purpose, as intended by both the Crown and the First Nations peoples’ (Mikisew para. 29, emphasis added). With this ‘underlying purpose’ referencing the assurance that the ‘same means of earning a livelihood would continue after the treaty as existed before it’ (Mikisew para. 30, emphasis added), and considering that ‘a large element of the Treaty 8 negotiations were the assurances of continuity in traditional patterns of economic activity ... and occupation’ (Mikisew para. 47, emphasis added), Treaty rights should be interpreted as the guarantee of a continuation of this ‘livelihood’. Recognising this, Laidlaw and Passelac-Ross (2014: 25) go on to note that ‘[t]his is the proper interpretation of Alberta’s numbered Treaties’, where ‘livelihood was and remains interwoven in the distinctive cultures of Alberta First Nations’. Treaty rights should therefore be taken to encompass a much broader suite of purposes beyond hunting, fishing and trapping for food. The Mikisew case (para. 44), also suggests that Treaty rights should be interpreted as both species- and location-specific, requiring that these be taken into account when determining factors that trigger the duty to consult. Indeed, the West Moberly First Nations v. British Columbia (Chief Inspector of Mines) 2011 (para. 138) describes the Mikisew case as ‘instructive on this point’. As such, First Nation criticisms highlight a very real discrepancy between the approach adopted by the ACO towards Treaty rights and the judgments of the SCC.

Criticism was also directed by participants at the level of policy and strategy, which influence the more operational aspects of the consultation process. One of the key issues identified was in relation to the Lower Athabasca Regional Plan (LARP), a land use strategy intended to guide development in the region of the oil sands. Of specific focus was its omission of First Nation input on conservation areas, parcels of land where development would be prohibited but which could continue on adjacent areas. Indeed, this is an example of First Nations conceding that some industrialisation would be of benefit, demonstrating an attempt to balance their own traditional, land-based practices with the need for wage labour. As such, during consultation, evidence-based recommendations were submitted as to the location of these areas, their size, proximity to communities on traditional territories, and suitability for supporting the surrounding ecosystem to ensure the continuation of activities tied to Treaty rights. However, the result of this costly and time-consuming exercise was the almost complete exclusion of First Nation inputs, which were subordinated to the economic value of oil sand deposits: ‘the major driver for deciding conservation areas, that had to be considered at the table with Alberta, was location of resources’ (Participant A, FNIRD 2). The primacy of economic reasoning underpinning such decisions was confirmed by Participant B from the LUS:

... if you look at the leases that have been sold by the Department of Energy on that landscape, then you look at the regional plan and the conservation areas that have been set out ... it probably doesn’t take a rocket scientist to figure out where the conserved land was in relation to the economic driver, right?

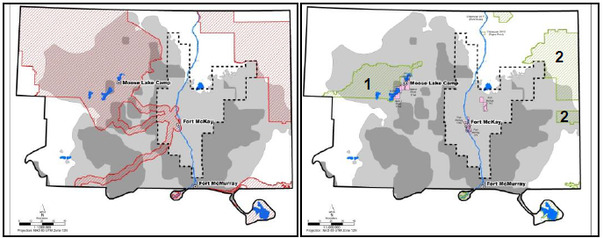

Figure 1 clearly supports this view, with the map on the left indicating conservation areas requested by a First Nation during consultation on the LARP and, on the right, those that were ultimately approved. The areas in grey denote recoverable oil sands deposit. Although initially appearing that some minor concessions were made here by the provincial government, this is incorrect. The shaded area marked ‘1’ is the Birch Mountains Wildland Provincial Park and those marked ‘2’ form the Marguerite River Wildland Provincial Park, both of which were established in 2000 under the Provincial Parks Act, creation of which had nothing to do with consultation on the LARP (Griffiths et al. 2001: 7).

(a) (b)

Figure 1: Requested conservation areas (a) vs. granted conservation areas (b)

Source: Nishi et al. 2013: 50-51

Notes: Conservation areas requested by a First Nation during consultation on the LARP shaded red in (a).

Ultimately approved areas shaded green in (b); area ‘1’ is Birch Mountains Wildland Provincial Park; area ‘2’ is Marguerite River Wildland Provincial Park.

Recoverable oil sands deposits shaded grey in (a) and (b).

Ultimately, although the Government of Alberta have established some conservation areas following consultation with First Nations (see Government of Alberta 2012: 92-93), these have been primarily granted at locations not intersecting with the oil sands deposit. Put another way, the interests of First Nations have been subordinated to a perception of oil sands as the priority source of value in the region.

Although the ACO attracted considerable criticism, their approach is dictated by the 2013 policy on consultation. Despite a broad range of participants recognising that the narrow interpretation of Treaty rights is rooted in this policy, this was frequently accompanied by concurrent recognition that the policy was finalised without adequate integration of First Nation input. Indeed, engagement with First Nations on both the 2005 and 2013 policies bear similarity to the consultation process deployed in development of the LARP, in that they both excluded substantial proportions of indigenous input:

So, we came out with our first policy in 2005, we came out with our next policy in 2013. The first one didn’t work, wasn’t supported by First Nations, so we kind of scratched our head; okay what did we get wrong? We asked them, let’s talk about that. [They said] ‘Well, you didn’t engage us the way we wanted to be engaged’. So, in 2008 we went into a policy review that took years, and we engaged one to one with each community, but it was the same model. Go out and look for it, seek input, and then bring it back and see what you can come up with. We did that for this policy; still not supported. (Participant A, ACO)

This approach was not only recognised in specific relation to Alberta’s consultation policy but was also viewed as characteristic of the province’s approach to consulting with First Nations more generally, a feature which is dictated by these underpinning policies on consultation:

The push back ... not just for First Nations but for Aboriginal Peoples in general, is government like to come out and say ‘hey, this is what we’re doing, tell us what you think’, and then they go back and write out their policy and their paper and they’ve never included a single thing of what they’ve heard. (Participant D, AER)

What we’ve traditionally done is we’ll say ‘okay, we’re going to develop a policy around this and we’ll go consult and we’ll gather up this information input, from Aboriginal communities and other stakeholders, and we’ll take it back, dissect it and analyse it, come up with something and then put it back out and say, you know, here’s our policy, thanks for the input’. The reality is that it doesn’t work in the Aboriginal context. I’ve never seen it work and I’ve been doing this work now for over a decade. It just doesn’t work. (Participant A, ACO)

Ultimately, the situation experienced by First Nations, with regard to their input into both the 2005 and 2013 policies on consultation, is one characterised by repeated marginalisation. Over a decade may have passed since the duty to consult was enshrined in law, but the lack of progress made during this time only lends further support to a comment made by one of the First Nation participants: ‘[i]t’s an attitudinal change that’s required; the attitude of government to the duty to consult [and] Treaty rights. They pay lip service to consultation’ (Participant B, FNIRD 1).

The distributional injustice experienced by First Nations for almost two decades, in the form of ‘cultural loss’, is facilitated by a consultation process characterised by the core features of its procedural counterpart; marginalisation and misrecognition. Taking the first of these components as a point of departure, First Nations are excluded at key stages. At the very beginning, land has already been divided up amongst oil industry proponents by the time consultation is required by the ACO. First Nation input is therefore gathered too late for it to influence project placement. This is despite procedural Treaty rights requiring that consultation be triggered at this earlier point and not after. First Nations are acknowledged at a subsequent stage but the marginalisation continues, as they are discouraged from raising concerns about the cumulative effects of oil sand projects. Even when these issues are broached, industry refuse to acknowledge them because the LARP is seen as the solution. However, even this overarching land use plan excluded indigenous input prior to its publication, where the economic value of the oil sands resource was given priority over First Nation interests. Several markers of the participatory element of procedural injustice are thereby demonstrated, including the exclusion of ‘non-elite’ voices at key points of the process (Walker 2012), opportunity for only a narrow field of review (Hunold and Young 1998), the refusal to acknowledge issues raised by those who are included (George and Reed 2017), and a lack of accommodation that reduces consultation to ‘an empty ritual of participation’ (Arnstein 1969: 216).

Although an injustice in and of itself, this marginalisation is accompanied by an equally systemic misrecognition of First Nation Treaty rights. This occurs where the ACO uses its discretion to evacuate them of their materiality, and where it limits the right to hunt, fish and trap to food only. While at first appearing to be more a question of law than justice, this is not so, largely because the two spheres are entwined when discussing First Nations. This accords with the conceiving of recognition as a remedy for injustice, where Fraser (2001) was careful to sensitise it to the distinctive status or rights of specific groups. This is because the forms required in any given instance depend on the types of misrecognition to be redressed:

In cases where misrecognition involves denying the common humanity of some participants, the remedy is universalist recognition ... Where, in contrast, misrecognition involves denying some participants’ distinctiveness, the remedy could be recognition of specificity. (Fraser 2001: 30)

Not only does this acknowledge that the recognition needs of subordinated actors differ to those of dominant actors, it also appreciates that addressing such differences may be required to overcome obstacles to injustice. In this sense, to address unequal participation in decision-making, some groups ‘may need to have hitherto under acknowledged distinctiveness taken into account’ (Fraser 2001: 31).

For First Nations, this specificity is demonstrated through their cultural identity or ‘indigeneity’ (see Wolfe 1999), of which Treaty rights are a legal expression. If ‘culture’ is recognised as ‘the set of distinctive spiritual, material, intellectual and emotional features of a society or a social group’, encompassing ‘art and literature, lifestyles, ways of living together, value systems, traditions and beliefs’ (UNESCO 2001: 1, emphasis added), the distinctiveness of indigenous peoples lies in their cultural relationship with the land. As Woolford (2009: 91) describes it, their conceptions of nature and culture are ‘braided’ to one another, representing not simply a ‘closeness’ or reliance upon nature, but an ‘embodied inscription’, where land and wildlife form a central component to their collective indigenous identities. This still underpins the cultural identity of First Nations in and around the oil sands today. Their indigeneity is ‘reflected and embedded in practices ... between people and their natural environment’ (Gibson 2017: 8). As McCormack (2012: 125) explains, ‘history, culture and religion are both encoded and demonstrated in the geography of their traditional territory’. Hunting, fishing and trapping rights stand as testament to this. They are a legal expression of the indigenous will to protect these specific, land-based practices across generations. As such, the misrecognition demonstrated in the narrow and diluted interpretation of Treaty rights is not a matter of illegality or injustice, but illegality and injustice. This echoes the point made by George and Reed (2017), where the lack of special consideration given to adversely affected and previously marginalised groups is a hallmark of misrecognition-as-injustice.

While marginalisation and misrecognition are manifested at different points in the consultation process, this belies a far more iterative and entwined relationship between the two components. Both the 2013 and 2005 policies on consultation grant the ACO enough discretion to abstract hunting, fishing and trapping practices from the material environment. This enables the government agency to make a determination of ‘adequacy’ at a point prior to which indigenous concerns can be addressed. Yet, each of these consultation policies were devised with little accommodation of First Nation input. As such, indigenous voices are not only marginalised at the level of project-by-project consultation due to a narrow interpretation of Treaty rights, but this is also facilitated by their previous, higher level marginalisation on the provincial consultation policies that inform it. The same observation can be made about the LARP, which allows for the similar marginalisation of indigenous concerns pertaining to cumulative environmental effects. However, by virtue of their procedural Treaty rights, which are tied to the distinctiveness of First Nations, such marginalisation is also a form of misrecognition. Simply put, this is because their marginalisation simultaneously misrecognises their procedural right not to be marginalised. In this sense, the two components of procedural injustice systematically and cyclically reinforce one another at different levels, restricting meaningful First Nation involvement in decision-making and generating the distributional injustice of cultural loss.

In response to the distributional conception of environmental justice deployed throughout green criminology, this article has demonstrated how its procedural counterpart can be used to examine the decision-making processes underpinning such distributions. In doing so, it has sought to clarify how justice-as-recognition and justice-as-participation are jointly manifested within the concept of procedural environmental justice. By applying this to the process of First Nation consultation that occurs on oil sands projects in Alberta, Canada, the article also adds to existing literature on this specific case. Showing how the two components of procedural injustice—marginalisation and misrecognition—reinforce each other at the levels of operations and policy, the article illustrates how the resulting dismissal of First Nation distinctiveness underpins the distributional injustice of ‘cultural loss’ experienced. In doing so, it also expands on existing macro-level accounts of environmental harm in the region by explaining the role of provincial regulatory mechanisms in its production and reproduction.

The implications pertain to both the case itself and green criminology. With regard to the former, politicians in Alberta should reassess the interpretation of Treaty rights outlined in existing consultation policy. Aligning it with those of First Nations and the Supreme Court of Canada would contribute to a reduction in procedural and distributional injustice, also pre-empting a possible challenge in the courts, of which it is currently vulnerable. Further research is also needed on the dematerialised interpretation of Treaty rights, as it is not rooted in policy. Borne of the more operational realm, more information is needed on how its use is justified by the regulatory personnel responsible for operationalising it. With regard to green criminology more broadly, it would be fruitful for future research to explore other instances of procedural injustice. This would render the sub-field more attentive to operational dynamics that are unjust in and of themselves, as well as those serving to produce more distributional forms of environmental injustice.

Correspondence: Dr James Heydon, Lecturer in Criminology, School of Social and Political Sciences, College of Social Science, University of Lincoln, Brayford Way, Brayford Pool, Lincoln LN6 7TS, United Kingdom. Email: jheydon@lincoln.ac.uk

Adler P and Adler P (2002) The reluctant respondent. In Gubrium J and Holstein J (eds) Handbook of Interview Research: Context and Method: 153-157. London: Sage Publications.

Arnstein S (1969) A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Planning Association 35(4): 216-224. DOI: 10.1080/01944366908977225.

Braun C and Clarke C (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3(2): 77-101. DOI: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Brighouse H (2004) Justice. Cambridge, England: Polity Press.

Brisman A (2014) Of theory and meaning in green criminology. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 3(2): 21-34. DOI: 10.5204/ijcjsd.v3i2.173.

Castree N (2004) Differential geographies: Place, indigenous rights and ‘local’ resources. Political Geography 23: 133-167. DOI: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2003.09.010.

Chastko P (2007) Developing Alberta’s Oil Sands. Calgary, Alberta: University of Calgary Press.

Davies P (2017) Green crime, victimisation and justice: A rejoinder. Critical Sociology 43(3): 465-471. DOI: 10.1177/0896920516689071.

Dorcey A, Doney L and Rueggeberg H (1994) Public involvement in government decision making: Choosing the right model. British Columbia Round Table on the Environment and the Economy. Victoria, British Columbia: The Round Table.

Fraser N (1996) Social justice in the age of identity politics: Redistribution, recognition and participation. The Tanner Lectures on Human Values. Stanford, California: Stanford University.

Fraser N (1999) Social justice in the age of identity politics: Redistribution, recognition, and participation. In L Ray and A Sayer (eds) Culture and Economy after the Cultural Turn: 25-52. London: Sage Publications.

Fraser N (2001) Recognition without ethics? Theory, Culture and Society 18(2-3): 21-42. DOI: 10.1177/02632760122051760.

Fumoleau R (2004) As Long as This Land Shall Last: A History of Treaty 8 and Treaty 11, 1870-1939. Calgary, Alberta: University of Calgary Press.

George C and Reed M (2017) Revealing inadvertent elitism in stakeholder models of environmental governance: Assessing procedural justice in sustainability organisations. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 60(1): 158-177. DOI: 10.1080/09640568.2016.1146576.

Gibson G (2017) Culture and Rights Impact Assessment. Available at: http://www.thefirelightgroup.com/thoushallnotpass/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/MCFN-303_MAPP-Report_Final.pdf (accessed 7 August 2018).

Government of Alberta (2005) Alberta’s First Nations Consultation Guidelines on Land Management and Resource Development. Available at http://indigenous.alberta.ca/documents/2005_Policy_and_Guidelines.pdf?0.40955977142790834 (accessed 21 February 2018).

Government of Alberta (2010) Oil Sands Tenure Regulation. Alberta Regulation 196/2010. Edmonton, Alberta: Alberta Queens Printer.

Government of Alberta (2012) Lower Athabasca Regional Plan. Available at https://landuse.alberta.ca/LandUse%20Documents/Lower%20Athabasca%20Regional%20Plan%202012-2022%20Approved%202012-08.pdf (accessed 21 February 2018).

Government of Alberta (2013) The Government of Alberta’s Policy on Consultation with First Nations on Land and Natural Resource Management, 2013. Available at http://indigenous.alberta.ca/documents/GoAPolicy-FNConsultation-2013.pdf?0.4702485625586763 (accessed 21 February 2018).

Government of Alberta (2018) Total Oil Sands Production Graph. Available at http://osip.alberta.ca/library/Dataset/Details/46 (accessed 21 February 2018).

Government of Canada (1899) Treaty Texts—Treaty No. 8. Available at http://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1100100028813/1100100028853#chp4 (accessed 21 February 2018).

Goyes D and South N (2016) Land-grabs, biopiracy and the inversion of justice in Colombia. British Journal of Criminology 56(3): 558-577. DOI: 10.1093/bjc/azv082.

Goyes D and South N (2017) The injustices of policing, law and multinational monopolization in the privatization of natural diversity: Cases from Colombia and Latin America. In Rodriguez D, Mol H, Brisman A and South N (eds) Environmental Crime in Latin America: 187-214. London: Palgrave.

Griffiths M, Wilson S and Anielski M (2001) The Alberta GPI Accounts: Parks and Wilderness. Available at http://www.pembina.org/reports/21_parks_and_wilderness.pdf (accessed 21 February 2018).

Heydon J (forthcoming, 2019) Indigenous environmental victimisation in the Canadian oil sands. In South N and Brisman A (eds) The International Handbook of Green Criminology, 2nd edn. London: Routledge.

Hunold C and Young I (1998) Justice, democracy and hazardous siting. Political Studies 46(1): 82-95. DOI: 10.1111/1467-9248.00131.

Huseman J and Short D (2012) A slow industrial genocide: Tar sands and the indigenous peoples of Northern Alberta. International Journal of Human Rights 16(1): 216-237. DOI: 10.1080/13642987.2011.649593.

Kosmicki S Long M (2016) Exploring environmental inequality within US communities containing coal and nuclear power plants. In Wyatt T (ed.) Hazardous Waste and Pollution: 79-99. Online: Springer. Available at https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-18081-6_6 (accessed 6 August 2018).

Laidlaw D and Passelac-Ross M (2014) Alberta First Nations consultation and accommodation handbook. Canadian Institute of Resources Law Occasional Paper #44. Calgary, Alberta: University of Calgary.

Lynch M and Stretesky P (1998) United class and race with criticism through the study of environmental justice. The Critical Criminologist 1: 4-7.

Lynch M and Stretesky P (2012) Native Americans and social and environmental justice: Implications for criminology. Social Justice 38(3): 104-124.

Lynch M, Long M and Stretesky P (2016) A proposal for the political economy of green criminology: Capitalism and the case of the Alberta tar sands. Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice 58(2): 1-24. DOI: 10.3138/cjccj.2014.E38.

Lynch M, Stretesky P and Long M (2015) Environmental justice: A criminological perspective. Environmental Research Letters 10: 1-6. DOI: 10.1088/1748-9326/10/8/085008.

McCormack P (2012) Research Report: An Ethnohistory of the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation. Edmonton, Alberta: Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation. Available at https://ceaa-acee.gc.ca/050/documents_staticpost/59540/82080/Appendix_D_-_Part_03.pdf (accessed 7 August 2018).

Nishi J, Berryman J, Stelfox A, Garibaldi A and Straker J (2013) Fort McKay Cumulative Effects Project: Technical Report of Scenario Modelling Analysis with ALCES. Victoria, British Columbia: Integral Ecology Group.

Penrod J, Preston D, Cain R and Starks M (2003) A discussion of chain referral as a method of sampling hard to reach populations. Journal of Transcultural Nursing 14(2): 100-107. DOI: 10.1177/1043659602250614.

Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, Baker S, Waterfield J, Bartlam B, Burrows H and Jinks C (2017) Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualisation and operationalization. Quantity and Quality 52(4): 1893-1907. DOI: 10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8.

Schlosberg D (2007) Defining Environmental Justice. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Schrader-Frachette K (2002) Environmental Justice: Creating Equality, Reclaiming Democracy. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Silverman R (2005) Caught in the middle: Community development corporations (CDCs) and the conflict between grassroots and instrumental forms of citizen participation. Journal of the Community Development Society 36(2) 35-51. DOI: 10.1080/15575330509490174.

Smandych R and Kueneman R (2010) The Canadian-Alberta tar sands: A case study of state-corporate environmental crime. In White R (ed.) Global Environmental Harm: Criminological Perspectives: 87-109. Devon, England: Willan Publishing.

Stretesky P and Hogan M (1998) Environmental justice: An analysis of superfund sites in Florida. Social Problems 45: 268-284. DOI: 10.2307/3097247.

Stretesky P and Lynch M (2002) Environmental hazards and school segregation in Hillsborough County, Florida, 1987-1999. Sociological Quarterly 43: 553-573. DOI: 10.1111/j.1533-8525.2002.tb00066.x.

Taylor A and Friedel T (2010) Enduring neoliberalism in Alberta’s oil sands: The troubling effects of private-public partnerships for First Nation and Metis communities. Citizenship Studies 15(6-7): 815-835. DOI: 10.1080/13621025.2011.600093.

Tritter J and McCallum A (2006) The snakes and ladders of user involvement: Moving beyond Arnstein. Health Policy 76(2): 158-168. DOI: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2005.05.008.

UNESCO (2001) Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity. Available at http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID=13179&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html (accessed 21 February 2018).

Walker G (2012) Environmental Justice: Concepts, Evidence and Politics. Oxon: Routledge.

Weinstock A (2017) A decade of social and environmental mobilization against mega-mining in Chubut, Argentinian Patagonia. In Rodriguez D, Mol H, Brisman A and South N (eds) Environmental Crime in Latin America:141-162. London: Palgrave.

White R (2007) Green criminology and the pursuit of social and ecological justice. In Beirne P and South N (eds) Issues in Green Criminology: Confronting Harms Against Environments, Humanity and Other Animals: 32-54. Devon, England: Willan Publishing.

White R (2008) Crimes Against Nature. Devon, England: Willan Publishing.

White R (2013) Environmental Harm: An Eco-Justice Perspective. Bristol, England: Policy Press.

Williams C (2012) Researching Power, Elites and Leadership. London: Sage Publications.

Wolfe P (1999) Settler Colonialism and the Transformation of Anthropology. The Politics and Poetics of an Ethnographic Event. London: Cassell.

Woolford A (2009) Ontological destruction: Genocide and Canadian aboriginal peoples. Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal 4 (1): 81-97.

Young I (1990) Justice and the Politics of Difference. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Zilney LA, McGurrin D and Zaharan S (2006) Environmental justice and the role of criminology: An analytic review of 33 years of research. Criminal Justice Review 32 (1): 47-62. DOI: 10.1177/0734016806288258.

Cases cited

Haida Nation v. British Columbia (Minister of Forests) [2004], Canada.

Mikisew Cree First Nation v. Canada (Minister of Canadian Heritage), Canada.

West Moberly First Nations v. British Columbia (Chief Inspector of Mines) 2011, Canada.

[1] This work was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council (Award No. ES/J500215/1).

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/IntJlCrimJustSocDem/2018/35.html