|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy |

David Rodríguez Goyes

University of Oslo, Norway; Antonio Nariño University, Colombia

|

Abstract

This article investigates the Red de Semillas Libres de Colombia

[Colombian Network of Free Seeds] movement, since its inception to date

(2013-2016). The study, developed within the framework of

green criminology and

with a focus on environmental justice, draws on ethnographic observations of Red

de Semillas and semi-structured

interviews with group members. I explore

processes of repertoire appropriation developed by social movements. The main

argument advanced

is that the Red de Semillas experienced a case of

‘tactics rebound’, in which tactics deployed at the global level

shaped

local tactics, bringing a set of problematic consequences. The article

starts by summarising key explorations of repertoires of contention

and

connecting them with framing theory propositions. My interest is to locate

processes of tactic appropriation in the context of

collective action frames. I

situate this theory in a study of the organisation and the tactics it used to

elucidate how the concept

of ‘collective action frame hierarchies’

can be used to explain instances of ‘tactics rebounding’.

Keywords

Collective action frames; food sovereignty; repertoire appropriation;

resistance tactics; seed sovereignty; social movements.

|

Please cite this article as:

Goyes DR (2018) ‘Tactics Rebounding’ in the Colombian Defence of Seed Freedom. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 7(1): 91-107. DOI: 10.5204/ijcjsd.v7i1.425.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Licence. As an open access journal, articles are free to use, with proper attribution, in educational and other non-commercial settings. ISSN: 2202-8005

Despite being the second most biodiverse country in the world, Colombia faces serious nutrition problems. In a situation described as lose-lose (Fischer et al. 2017), Colombia’s biodiversity is being degraded while its rural population is confronted by hunger. As of 2008, the Colombian hunger index was 6.7 and rising.[1] In 2009, 43 per cent of Colombian homes were in a state of food insecurity, indicating an increase of 1.9 per cent since 2005 (Instituto Colombiano de Bienestar Familiar (ICBF) [Colombian Institute of Family Wellbeing] et al. 2008). Paradoxically but not surprisingly, it is mainly the rural population that faces the most urgent case of food insecurity (Ministerio de Salud, y Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y la Agricultura [Ministy of Health, and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO)] 2013). Simultaneously, national agricultural production has decreased as progressively less fertile soil is used for cropping priority foods (ICBF et al. 2008). This has made the country increasingly dependent on imports to fill its food needs (Observatorio de Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutricional de Colombia [Colombian Observaory of Food and Nutrition Security] 2014).

In this context, two main models are used in Colombia to produce food: chagras and monocultures.[2] Chagras are spaces inhabited by humans and a wide diversity of animal and vegetal species, where a large array of foods are produced by the interaction and activities of all these beings (Bastidas 2013; Vargas Roncancio 2011). Chagras are the ancestral mode of food production in Latin America, and its origins can be traced back to pre-colonial times. They are a small-scale production system aimed at subsistence, dedicated to a variety of crops like cassava, plantain and local fruit trees. Monocultures, conversely, are spaces of low biodiversity, where humans manipulate all factors by excluding animals and using chemical fertilizers, pesticides, machinery, and so on. Only one product is farmed at any given time (Borlaug 1968; Moore 2000). Ironically, seeds are the foundational element in both models, albeit understood in vastly different ways. In chagras, seeds are freely and widely distributed via bartering. Chagra supporters seek to preserve the largest diversity of seed species possible. Meanwhile, in the monoculture model, intellectual property rights restrict the free use and exchange of seeds. Furthermore, the monoculture model calls for the genetic ‘improvement’ of a reduced number of selected seeds.

Amidst the dramatic Colombian situation of malnutrition and, as an outcome of the perceived irreconcilability of these two models of food production, Red de Semillas Libres de Colombia [Colombian Network of Free Seeds] was created in 2013, seeking to transform current seed management in the country. This article is an empirical study focused on uses and representations of seeds in Colombia and on the resistance tactics implemented by Red de Semillas. I use social movement theory to analyse Red de Semillas, given that it ideally fits the definition of a social movement as an organised actor that arises from the perceived threat of losing its sovereignty or the hope of claiming it, and which then takes part in a conflict ‘over the social use of common cultural values’ (Touraine 2002: 90). The main theoretical insight advanced here is that Red de Semillas experienced a case of ‘rebounding’ tactics in which tactics deployed at the global level shaped local tactics, with problematic consequences. This study was developed within the framework of green criminology, with a focus on environmental justice. Environmental justice is a perspective that seeks to achieve social justice by denouncing and countering the unfair, uneven and discriminatory distribution of ‘environmental goods’ (for example, a clean environment often enjoyed by privileged groups) and ‘environmental burdens’ (for example, a contaminated environment often imposed on marginalised groups). Consequently, in this article, the efficacy of the collective action of this grassroots movement in Colombia is studied, with the intent of supporting their struggle to transform current dynamics that produce environmental and social injustice in Colombia.

As Crossley (2002) acknowledges, ever since the appearance of Tilly’s (1977) pioneering study about ‘repertoires of collective action’, social movement studies have been interested in exploring methods of protest used by social movements. From Tilly’s interest in the formation and changing of repertoires, understood as the forms of action actually available to a group (Tilly 1978), research has focused on ‘repertoire appropriation’, which seeks to understand how social movements choose the specific techniques they enact from the available repertories (Crossley 2002).

Part of the study of repertoires has been trying to understand how global integration affects social action (Smith 2001). Relevant for understanding processes of appropriation is Roggeband’s hypothesis (2007) of cross-national repertoire diffusion: repertoires that have been implemented by social movements around the world will be more easily adopted by counterparts in other regions without further need of legitimation. I contend that framing theory can help to provide a macro explanation to processes of repertoire appropriation.

Framing theory addresses realist approaches by asserting that social movements do not depend on external political opportunities but have agency in framing their own political opportunities through the use of language (Sandberg 2006); the ability to construct schemata of interpretation used by individuals to attach meaning to events and occurrences will affect the success of participant mobilisation. The schemata built in active and processual ways by social movements is referred to as ‘collective action frames’ (Benford and Snow 2000). Thus, collective action frames can be understood as the beliefs and meanings that inspire and legitimate social movement activities and campaigns and articulate events and experiences so that they cohere in a unified and meaningful fashion (Benford and Snow 2000; Sandberg 2006). Social movements can have internal battles over which particular frame should prevail but, in order to mobilise action, a frame must prevail (Gamson 1995).

Benford and Snow (2000) proposed that collective action frames have three characteristic features (also called ‘framing tasks’): diagnostic—problem identification; prognostic—what can be done about the problem; and motivation—the motive or rationale for mobilisation. Gamson (1995) proposed that collective action is framed by three things: injustice—the intellectual and emotional moral indignation over actions of authority defined as unjust; agency—the recognition of the possibility for altering the conditions of injustice through collective action; and identity—which helps avoid abstraction of the targets of collective action by constructing movement protagonists (good/us) and antagonists (evil/they). The characteristic features of collective action frames proposed by Benford and Snow on the one hand, and by Gamson on the other, are not mutually exclusive but can be synthesised; in other words, collective action frames are composed by diagnostics (injustice), prognostics, motivation (agency) and identity.

The existence of frames does not imply that their characteristic features are not contested within a group; for instance, in many cases, immediate agreement on the diagnostic within a movement is lacking, something that frequently leads to intra-movement conflict (Benford and Snow 2000). Relying on the tools offered by framing theory, the present study will probe into the elements present in those processes of tactic appropriation.

There has been no study theorising the tactic appropriation developed by the many social movements championing seed freedom around the world. Nonetheless, some explorations give us cues about the tactics they implement and the dynamics underlying their appropriation.[3] Kloppenburg (2010) describes La Vía Campesina [The Peasant Way], a transnational social movement partly inspired by Latin American contributions with significant inputs from North America, Europe and Asia (Desmarais 2007), as leading and connecting social mobilisation around the world in defence of seed freedom, which in turn has encouraged the implementation of similar tactics in diverse global locations. A literature review confirms Kloppenburg’s claim. Ever since La Vía Campesina launched its campaign ‘Seeds: Patrimony of rural peoples in the service of humanity’ in India in 2000 (Martínez-Torres and Rosset 2010), several social movements have appropriated its tactics, confirming Roggeband’s (2007) hypothesis that, as groups adopted the campaign, the tactics deployed gained momentum and were swiftly appropriated by many more.

The Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra [Movement for Landless Rural Workers] in Brazil, the French Peasant Seed Network, movements in the United States fighting for alternative production systems, the Zapatistas in Mexico, the Indian ‘Seed Freedom Movement’ and other movements in Mali and Indonesia have all implemented four main tactics:

1) banning genetically modified seeds;

2) starting a campaign of free and wide seed distribution that encompasses recovering and reviving scarce heirloom seed varieties and exchanging both these seed varieties and the associated peasant knowledge;

3) establishing seed libraries/banks to save, lend and share seeds; and

4) using the counter hegemonic discourse of ‘native seeds’ and ‘peasant identity’.

Because of the many examples of social movements that implement the same set of tactics, it can be argued that, through cross-national diffusion, a set of globalised tactics has come into existence that is now locally enacted by most local movements that form part of the ‘seeds struggle’. This is not to say that the impact goes only from the global to the local, but rather that the current accumulated result of past bi-dimensional processes, where the local shaped the global at least with the same intensity as the global shaped the local, is the formation of a standardised set of tactics now used in diverse locations of the world where the seeds struggle is taking place.

However, identifying the global tactics used in the defence of seed freedom does not provide a theoretical explanation of the local appropriation of them. I therefore turn to the Colombian case of Red de Semillas. The Colombian case is further interesting because, whereas in Colombia the legal and economic systems are similar to those of other countries where globalised tactics are used, there are also important and highly visible differences. The Colombian rural context is one of economic poverty and violence. It has been demonstrated in social movements studies that the action of social movements in poor and violent contexts is different from the action of their counterpart in more democratic societies. Social movements in the former scenarios do not count with the same resources as their counterparts in more democratic societies, must face permanently shifting frames that make it harder to convey to the larger society the sense of injustice are fighting against, and have to adopt non-confrontational tactics (Domingo and O’Neil 2014; Lemaitre and Sandvik 2015)[4].

Agreeing on the importance of defending seed freedom as an act of sovereignty, Red de Semillas[5] was established in 2013 by the joint efforts of traditional communities and non-government organisations (NGOs) building on previous efforts of regional networks such as the Network of Guardians of Nariño. Its goal was to resist the actions of multinational seed corporations and governmental institutions, which, according to members of Red de Semillas, imposed monocultures and privatised seeds. The resources used by Red de Semillas for its activities come from three main sources: 1) the sporadic capital obtained from funding grants from diverse national institutions; 2) the voluntary work of the members of the movement, particularly NGO staff; and 3) its infrastructure. Red de Semillas is led by the central ‘node’ located in Bogotá and has a node in each Colombian region. The local nodes are responsible to organise the activities within their respective regions and disseminate the information received from the central node. Volunteers in the central node coordinate the communication activities that link the coalition members from diverse Colombian regions.

Red de Semillas is, therefore, a coalition of NGOs and traditional communities.[6] It has ‘itinerant dynamics of participation’, according to one of its coordinators, which makes it difficult to measure the exact membership count. However, 381 registered participants, including peasants, indigenous, Afro-descendants and scholars, attended the latest national meeting held in 2015. Additionally, Red de Semillas depends on the regular participation of two NGOs and the sporadic participation of three more. Key decisions are taken during an annual general meeting, attended by representatives from throughout the country. Nonetheless, due to difficulties in travelling and accessing the Internet, the exchange of information is often done through NGO visits to the communities.

The name ‘Red’ (Spanish for ‘network’) works as metaphor of the dynamics of the organisation. A male peasant explained to me that Red de Semillas has been ‘knitted’ by its members and that it is open to anyone ‘with the same will to defend the preservation of our seeds’. In this sense, the use of ‘Red’ goes beyond a structural understanding of networks as mere bridging processes that facilitate participation (Snow, Zurcher and Ekland-Olson 1980), but conjures up the image of an ‘island of meanings’ composed of discourses, stories and meanings (Passy and Monsch 2014). According to an eloquent indigenous man, Red de Semillas chose to organise itself as a network because that allows the communities to remain sovereign in spite of being part of an organisation, to adapt to circumstances by sharing and implementing the diverse knowledge that its members have, and to empower spatially marginalised peoples. As he said: ‘a network is about finding common worries and knowing that we are not alone’.

This article is based on sixteen semi-structured interviews, two focus group sessions, a study of campaign and informational material provided by the research participants, and ethnographic notes taken during visits to six traditional communities. Although a problematic term in some regards, I refer to the participants of this research as ‘traditional’. Admittedly, with this term I lump indigenous peoples and peasants into one group; nevertheless my intention is to avoid conflating or essentialising them. I gather them under the same denomination because, as members of Red de Semillas, they share an understanding of the seed struggle. I am aware that the term ‘peasant’ is considered derogatory in some contexts, as is the parallel Spanish term ‘campesino’. Nonetheless, I knowingly use the term ‘peasant’ (campesino) to draw attention to the valuable cultural and ethnic identity of these people. The deliberate use of this term is part of the fight against the misrepresentation of peasant communities, which leads to cultural degradation.

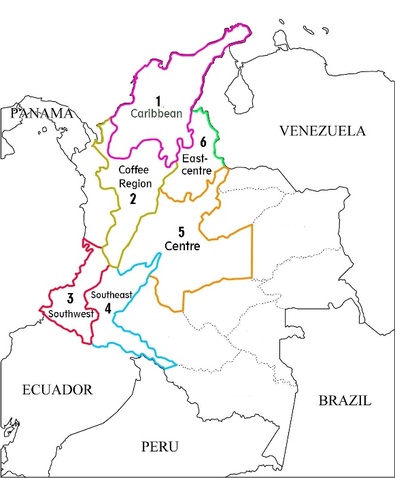

I visited all six geographical regions represented in the coalition (see Figure 1) to collect ethnographic observations and conduct on-site focus group sessions and semi-structured interviews with community representatives. I conducted fieldwork in Colombia from November 2015 to February 2016.

Interviewees were asked what hindered the continuation of traditional uses of seeds, their direct relation to this problem, how they were responding, their motivation to resist, the kind of work they developed as members of Red de Semillas, and any other considerations they thought important. Participants in the focus group sessions were representatives of traditional communities. The groups were moderated in a way that allowed me to collect information about the cultural framework of the group, the perceived problems around seeds, and the actions taken to confront them.

Figure 1: Regional divisions of Red de Semillas Libres de Colombia

The fieldwork fulfilled all requirements as established by Colombian law (Resolution 008430 of 1993) and was classified as ‘research without risk’. I received authorisation to conduct my project from the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (code 52095).[7] I have carefully followed the instructions regarding informed consent (articles 14-16 of Colombian Resolution 008430 of 1993). Consequently, all interviewees signed the informed consent form. They were told that their participation in the project was voluntary, that they could withdraw their consent at any time, that what they said would be recorded and transcribed, that the transcriptions and information they shared with me would only be available to me, that some extracts from the interviews might be used in publications, and that the information would be retained in storage no later than July 2018. Furthermore, ethical considerations for the research project of which this article is product are both extrinsic, in the sense that codes of conduct were followed and external committees were involved in the process, and intrinsic, given that the desires, expectations and needs of the participants were part of the research. Consequently, I not only obtained informed consent but also had a conversation about what the interviewees expected me to do with the information I collected. All of them requested that I produce a study that would help them develop more effective action against seed privatisation.

The Red de Semillas Libres de Colombia builds its identity via the value that its members ascribe to native seeds. Seeds are of great importance to the traditional communities that are part of Red de Semillas in both symbolic and practical terms. Highlighting the practical importance of seeds, an indigenous person stated that a seed ‘is the essence, is the mother of plants, and is our hope to nurture humanity and the pacha mama [mother earth]. Seeds take care of our families generation after generation’. Explaining the symbolic relevance of seeds, another indigenous person said that a seed ‘has much power because it is food. If a community has food, it is autonomous, it can make its own decisions, it does not need to kneel to others. A seed is the political exercise of autonomy’. Such an understanding of seeds motivate traditional communities to defend seed freedom, which they understand as those seeds that are free to be used by everyone.

The practical and political significance of seed freedom has led communities to link them with a broader set of resistance ideals. Traditional communities want to protect their seeds to achieve food sovereignty as the fundamental expression of freedom and independence.[8] A peasant explained that ‘the sovereignty issue is not romantic speech, to lose sovereignty implies to depend on others [so] if someone has the monopoly over seeds he can say “here you have some food, but here are the conditions for you to get it”’. Secondly, the defence of seeds is also strongly connected with the defence of land. They see the free use of seeds as a prerequisite to secure permanence on their ancestral lands, something that is not seen as a fight over property but as the right to live according to their own conceptualisations of ‘being’ (Escobar 2016). Thirdly, they link seed freedom with the protection of traditional culture and the strength of a community’s social fabric. Traditional communities criticise the disruptions that market practices have created to traditional communitarian practices through the privatisation of seeds because, for them, the exchange of seeds represents an opportunity to bond with other community members and thus strengthen the social fabric of their communities.[9] This no longer happens because now their relationships is with big seed corporations. Consequently, getting seeds has been reduced to a swift impersonal transaction. Finally, communities also expressed health concerns as a reason to defend seed freedom.

Despite sharing an identity derived from the importance of defending seed freedom as an act of sovereignty, two sets of diagnostics/injustices are present in the collective action frame of Red de Semillas. One set was provided by the traditional communities that are a part of Red de Semillas (three bundles of threats), and the other one was introduced by the NGOs that participate in Red de Semillas (see section herein headed ‘Another diagnostic’).

Members of traditional communities mentioned a wide range of interrelated dynamics that, according to them, are the structural machinery that has led the largest portion of members of traditional communities to use seeds provided by corporations, to the detriment of freely available seeds.

1) Monoculture indoctrination, food-security programs and the acts of federations and banks compose a first and important bundle in this machinery. Traditional communities argued that they have been indoctrinated by the mentality promoted by the green revolution, according to which productivity, cropping a single product, and making a profit are the only matters of import; all are held responsible for the disappearance of chagras. Federations (like the Colombian Coffee Growers Federation) play an important role in the implementation of monocultures because they pressure communities to use private seeds and crop only one product at the time. A woman peasant told me that ‘you have to follow their orders because they are the only ones buying what we produce’. Banks (like the Colombian Agrarian Bank) have also been instrumental in the imposition of monocultures. When peasants request loans, instead of being allowed to use their own freely available seeds, they are often obliged to use a corporate-owned seed as well as the inputs necessary to crop it and the required technical support, all of which make communities dependent on having continuous access to those products and services. Finally, governmental food security programs (like the Food Security Network Program) have had a similar effect because they offer ‘free’ access to seeds as long as big companies provide those seeds.

2) A second bundle of dynamics comprises the stigmatisation of free seeds, ‘cleanness’ discourses, and difficulties of access to free seeds, impeding rural populations from using them. Reminiscent of Mary Douglas’s classic work (2005 [1966]) about the danger of purity discourses (for a contemporary study see Bonneuil and Thomas 2009), some interviewees suggested that the concept of ‘clean’ resulted in some seeds being stigmatised and considered food for pigs. Profiting from that discourse, corporations have spread the idea that they are the only ones capable of producing ‘clean’, worthy seeds. With free seeds discredited, finding them is difficult as nobody wants to commercialise them. An indigenous woman summarised the dynamics of this second bundle as follows: ‘if you go to the market square, you will only find three varieties of seeds because that is what the market demands. You will never find traditional free seeds, because the market says that “that is food for pigs”’.

3) The third bundle of problems is associated with land grabs and the deruralisation of the Colombian countryside. Land grabs have taken place extensively throughout Colombia. If the people using free seeds do not have somewhere to crop them, these seeds will not be reproduced. An old peasant told me that ‘all those campesinos that had to migrate to the cities because of the war left behind the tradition of planting their own seeds. They will hopefully return to the countryside in some years, but they will not have their seeds any longer’. In addition, when young generations are displaced, they prefer to remain in the cities. Similarly, military conscription has also meant that, once young people are removed from rural territories, they do not want to return. Finally, the offer of better paying jobs for rural young people—in mining, for example—entails new generations of peasants no longer cropping their lands because better income is associated with higher social status.

According to the representatives of traditional communities that were interviewed, all these threats have undermined communities, affecting both their cultural aspirations, such as sovereignty, and their material living conditions. A peasant with extensive experience in the seed struggle stated that ‘we are now having difficulties sustaining ourselves with our own products, and we now depend on big corporations to fill our nutritional needs’. Food dependency has furthermore implied a risk to human lives and health, as evinced in the malnutrition present in rural regions (see introduction). Likewise, the social fabric of communities has been affected. As one peasant said, ‘losing control over our seeds has implied losing our culture, our tradition, and our identity’.

As is the case in many other Latin American social movements, NGOs are differentiable actors because of their particular traits (Massal 2014). Key for the present analysis is the global linkages created by NGOs, resembling the work of their counterparts in other regions of the world (Kloppenburg 2010). As the abundant literature on the relation between NGOs and social movements has indicated, the intervention of NGOs substantially alters the dynamics of social movements (specifically dealing with environmental issues, see, for example, Reimann 2001). In the case of Red de Semillas, NGO representatives participate annually in international conferences of transnational social movements and organisations like La Vía Campesina, Seed Savers, Grain, the Coordinadora Latinoamericana de Organizaciones del Campo [Latin American Coordination of Countryside Organisations], and the World Social Forum. With the support of international organisations like SWISSAID,[10] some representatives of traditional communities have joined the NGOs in participating in these forums. That is the first way in which transnational organisations influence the work of Red de Semillas. The influence of these transnational organisations on Red de Semillas further takes place in their collaboration on the production of Revista Semillas [Journal of Seeds],[11] which is the primary text on which Red de Semillas relies. Many of the issues of Revista Semillas include contributions from international organisations (see, for example, La Vía Campesina 2011) but also articles written by the staff of Colombian NGOs exploring how the situations denounced by the international contributors are also evidenced in Colombia. The inspiration gained from this journal has led the NGOs to use a combination of food-sovereignty and seed-sovereignty master frames in their framing activities in Red de Semillas (on food sovereignty framing, see Claeys 2014; on seed sovereignty framing, see Kloppenburg 2014).

NGOs have also played an important role in confronting the problems experienced by Red de Semillas, particularly those related to communication and the permanence of its members. They have done so by financing meetings, taking care of printing and distributing campaign and informational material and, in general, by making sure that the activities of Red de Semillas are continued. The overall interaction between traditional communities and NGOs has been harmonious partly because community members feel valued by NGOs and partly because both traditional communities and NGOs have tried to give priority to the views of the traditional communities. All NGO representatives interviewed agreed that decentralising the activities of Red de Semillas was a priority, thereby empowering the communities and equipping them to defend themselves, rather than making them dependent on NGOs support. These goals are well known and accepted by the communities.

However, although NGOs and traditional communities have a harmonious relationship, this does not ensure an equitable distribution of power. Communities see NGOs as guides in their resistance, assuming that NGOs better understand the problems experienced by the communities. This assertion is backed by my observations and the bulk of testimonies gathered during my research. In their meetings and in my observation of their activities, it was evident that traditional communities primarily implement the projects designed by the NGOs. A peasant expressed why this was so: ‘the people from outside can see the depth in our problems’. This is not to say that traditional communities are merely passive collaborators or that they lack agency; rather, this highlights the particularities of social mobilisation in impoverished contexts. Members of traditional communities are geographically isolated from one another, thus it is difficult for them to give significant shape to the shared discourses of the movement. Furthermore, they have to deal with daily challenges that prevent them from devoting time to reflecting on the activities of Red. As put by a community member, ‘the daily activities that we are obliged to face are as “small” as finding out how to feed our families, how to pay the bank loans, and how to travel to the big cities to receive medical treatment’. An indigenous man explained why traditional communities accept what NGOs propose: ‘[NGO X] has shown us the problems around seeds. [Person X] from [NGO X] was the one orientating us, he gave us the ideas, the steps to follow, and here we implemented them with the community’. For their part, NGOs have assumed the leading role. An NGO interviewee suggested that ‘traditional communities are trying to solve problems as they appear without noticing the “bigger picture”. Communities are very weak in the political realm; they know the general lines but they don’t have the full arguments’. Consequently, NGOs occupy a central role in Red de Semillas and are in a strong position to shape its discourses. As is pointed out in social movement literature, the capacity to shape discourses is of great importance for movements’ action because discourses determine the needs of organisations and the options open to them (Passy and Monsch 2014).

The intervention of NGOs, particularly through their links with international social movements, has meant that a diagnostic that differs from the one offered by the traditional communities has been created for Red de Semillas. As Benford and Snow (2000) explain, diverse diagnostics and prognostics can exist within a social movement. This seems to be particularly true for Red de Semillas. In addition to the complex dynamics that the communities identified, three more threats are part of the set of diagnostics of Red de Semillas as identified by the NGOs:

1) the laws that ‘want to privatise seeds’ and that ‘have “claws”, meaning that every use of any seed that circulates in the country without the due certificate is criminalised’ (interview with NGO representative);

2) seed seizures where ‘the Colombian Institute of Agriculture has a very strict control over seeds’ (interview with NGO representative); and

3) the introduction of genetically modified organisms (interview with NGO representative).

NGO discourses incorporated these three threats into the set of diagnostics of Red de Semillas, arguing that they were the most pressing dangers to the existence of free seeds. As will be shown next, those three threats match the globalised tactics responses in the ‘seed struggle’. The NGO diagnostic has entered the shared discourses of Red de Semillas and been accepted by the traditional communities. That these threats have been incorporated into the shared discourses of Red de Semillas through the NGOs, and not the traditional communities, is evinced in that none of the traditional communities I visited had actually experienced any difficulties related to these threats; they explicitly stated that the NGOs had informed the communities about them.

So far I have described Red de Semillas’ two sets of diagnostics, one provided by the traditional communities and one by the NGOs. In this section I describe the unified prognostic that Red de Semillas uses, which comprises three main resistance tactics. The tactics that compose this prognostic are listed below and are organised according to the importance that traditional communities assigned them. The contents of each tactic are described based on the explanation given by the communities. All of them coincide with the above-described globalised set of tactics in the defence of seed freedom. To clearly show this, the name used by international movements is presented in brackets following the Colombian designation. This correspondence further hints at the intervention of transnational forces in providing a repertoire of tactics but does not explain the elements that have led to their appropriation, an issue I turn to below.

1) Exchanging and planting free seeds (starting a campaign for the free and wide distribution of seeds): The main tactic used by Red de Semillas is to reinforce the traditional practice of freely exchanging and planting seeds. According to a young peasant, they ‘crop the seeds year after year and exchange them. Doing what we have always done’. An indigenous woman pointed out that Red de Semillas was created ‘with the intention of putting free seeds in free circulation’. The broad circulation of seeds, in addition to preventing them from disappearing, also prevents their appropriation through the use of intellectual property laws (threat number one in the NGO diagnostic). Major efforts are exerted by traditional communities into this resistance strategy. As a peasant said, ‘even if we have to exchange seeds in a hidden way, we do it. That means that what we are doing is criminal in the eyes of the government’.

2) Establishment of casas de semillas (establishing seed libraries/banks to save seeds): NGOs have financed casas de semillas (seed houses; see Figure 2) in four out of the six regions where Red de Semillas works (see Figure 2). Houses of members of traditional communities have also been adapted as casas de semillas in the two regions without seed houses. Casas de semillas serve two purposes: to facilitate seed and knowledge exchanges; and to store, classify and sometimes commercialise free native seeds in nonpublic locations, thus preventing seed seizures (threat number two in the NGO diagnostic).

3) Declaration of non-GMO zones (banning genetically modified seeds): Indigenous communities in the Colombian Caribbean and coffee region have made use of their special indigenous jurisdiction to legally declare non-GMOs zones. The special indigenous jurisdiction is a legal mechanism established in article 246 of the 1991 Colombian Constitution, by which indigenous communities have the authority to apply their own regulations in their territories. The use of this mechanism has made it possible for them to ban genetically modified seeds (threat number three in the NGOs diagnostic) in their territories. Peasant communities do not have this right but, with the assistance of an NGO that specialises in providing legal advice, Red de Semillas is seeking to expand this tactic to all of Columbia.

An exception: intracommunity loans. The three tactics just described are common to all regions where Red de Semillas works. In one region, however, traditional communities have also implemented the creation of intracommunity loans. These community funds enable community members to develop cropping projects without being forced to use private seeds. Each of the members of the communities that participate in the project contribute a small amount of money every month to a collective saving. When one of them has the opportunity to commercialise seeds/harvest, the savings are made available to that person without predatory lending.

There is clearly a disconnect between the threats identified by traditional communities and the tactics they enact, but a perfect match between the tactics enacted and the threats denounced by NGOs (see Table 1).

From the information so far provided, one question stands out: why is it that the traditional communities that are part of Red de Semillas have identified several bundles of threats menacing seed freedom, and yet enact the three resistance tactics promoted by NGOs, ones that do not clearly challenge their bundles of threats? I now turn to that question.

|

Threat

|

As identified by

|

Tactic

|

|

Monoculture indoctrination, food-security programmes and the acts of

federations

|

Traditional communities

|

An exception: intracommunity loans.

|

|

Stigmatisation of free seeds, ‘cleanness’ discourses, and

difficulties of access to free seeds

|

Traditional communities

|

|

|

Land grabs and the deruralisation of the Colombian countryside

|

Traditional communities

|

|

|

The laws that ‘want to privatise seeds’

|

NGOs

|

Exchanging and planting free seeds

|

|

Seed seizures

|

NGOs

|

Establishment of casas de semillas

|

|

The introduction of genetically modified organisms

|

NGOs

|

Declaration of non-GMO zones

|

Kinchy (2010) identified the importance of the international level in the action of social movements organised around seeds. She explored the ‘epistemic boomerang’ phenomenon in a case from Mexico where international experts helped citizens pressure the Mexican government to try to influence the shaping of policies dealing with genetically modified seeds. The case of Red de Semillas represents another instance where international tactics played an important role in the shaping of the tactics used by social movements to try to alter the existent seed-management system, which I refer to as ‘tactics rebounding’. The tactics currently implemented by many social movements championing seed freedom around the world were originally inspired by the lived experiences of grassroots Latin American social movements. With the intervention of La Vía Campesina, they were internationalised. Years later, and again through international interaction, they returned to their local roots and were immediately re-appropriated by local movements. This case of ‘tactics rebounding’ was predicted by Roggeband (2007: 249): ‘a transmitter or innovator at some point may adopt a reinvention of their original model’. Rebounding tactics are not the same as a top-down dynamic, but a dual process that departs from the local to the global and then returns from the global to the local.

In the case of Red de Semillas, the counter hegemonic discourses of ‘native seeds’ and ‘peasant identity’ have been used to construct a collective identity but not tactics. This is relevant in that Red de Semillas has been mobilised by making use of three out of four framing tasks of collective action frames: a shared identity; the acknowledgment of agency in the recovery of ancestral ways of cropping; and the establishment of a set of tactics as shared prognostics. Red de Semillas is, however, not unified by the diagnostic. While traditional communities acknowledge the existence of six main threats to the existence of free seeds, NGOs only recognise the existence of the three threats that they themselves have proposed. This allows for two propositions:

1) Hierarchies exist within the framing tasks of collective action. While Red de Semillas has identified six threats, the three tactics it enacts seek to respond to the threats described by NGOs. This would indicate that the NGO diagnostic has more force than that of the traditional communities. The existence of such a hierarchy in the diagnostics is explained by three reasons. First, given the privileged position that NGOs occupy within Red de Semillas, their discourses are prioritised over those of the traditional communities. Second, while the diagnostic made by traditional communities deals with a broad array of abstract sources (mental indoctrination, pressures by many social actors, stigmatisation of seeds, deruralisation, and so on), the diagnostic made by NGOs focuses on a few clearly graspable issues, thus its intelligibility helps create the impression of effectiveness in collective action (Sandberg 2006). Third, the tactics used by many social movements around the world that are part of the seed struggle correlate to diagnostics made by Colombian NGOs, not to those made by traditional communities. Consequently, the widespread use of those tactics contribute to their own legitimacy (Roggeband 2007) and to that of matching diagnostics.

2) Because hierarchies exist in the framing tasks of collective action frames, inverted processes in which prognoses constrain diagnostics are made possible. Benford and Snow (2000) assert that diagnostics and prognostics tend to be correlated, so that diagnostics constrain prognostics. However, in the case of Red de Semillas, an inverted process exists in which the global prognosis shapes the local diagnostic. Given the momentum that globalised tactics have in the seed struggle, they are likely to be adopted by local movements without further legitimation. As all framing tasks in a collective action frame are interrelated, and particularly those of diagnostic and prognostic (which demand a correlation), the strength of the global prognosis can constrain the local diagnostic. This contradicts the proposition made by Benford and Snow because, in the case of Red de Semillas, it is the prognosis that constrains the diagnostic. Having adopted globalised tactics, Red de Semillas has to point to matching local sources of conflict as the most pressing in order to present an image of coherence. This explains why Red de Semillas only implements three tactics, while leaving unchallenged the bundles offered by traditional communities. Those framing tasks capable of constraining others can be understood as higher up the hierarchy than the constrained ones. For instance, in Red de Semillas’ collective action frame, the prognosis is higher up the hierarchy than the diagnostic.

With this I contend that the existence of a collective action frame hierarchy is important in processes of tactics appropriation, particularly in the case of coalitions. In complex social dynamics, there is no unique, clear reality to which a social movement seeks to respond but, instead, perceptions of reality to which social movements seek to react. At the same time, social movements need to mobilise and, in order to do so, they need to generate coherent frames of collective action. The dissonance between the existence of varied perceptions regarding one or more of the framing tasks of collective action frames and the need for coherence among and within them can generate intra-movement conflicts (Benford and Snow 2000). Nonetheless, a unified coherent perception must prevail in order for a group to mobilise (Gamson 1995). This does not mean that forfeiting perceptions within a framing task disappear but, rather, that they are organised in a hierarchy. For instance, the diagnostic made by traditional communities is still present but subordinate to that made by NGOs. The interrelatedness of the four framing tasks means that the strength of one of them can solve conflicts in others. For example, in Red de Semillas, no agreement exists on the diagnostics; the strength of the NGOs’ prognosis made the NGOs’ diagnostic prevail. Thus, framing tasks can also be organised in a hierarchy within a collective action frame. The potency of the NGO’s prognostic was stronger than any of the diagnostics in conflict with each other. Consequently, the prognostic was positioned above the conflictive diagnostics. This results in tactic appropriation not necessarily being constrained by diagnostics, as Benford and Snow (2000) suggested, but, rather, being shaped by hierarchies among and within framing tasks and dependent on the relative potency of each framing task within a collective action frame. Whereas, in this case, the prognostic was high up in the hierarchy, thus giving a banal appearance to the argument (tactics were appropriated because they were potent), the relative potency of any other framing task can lead the process of tactic appropriation. In the situation of Red de Semillas, a more efficient mobilisation against the appropriation of seeds would be where the diagnostic developed by traditional communities was the most potent element, making it capable of leading tactic appropriation.

In this article, I have explored the implications of using framing theory for the study of processes of repertoire appropriation. The case used was the conflict existent in Colombia around seed representation and management. When studying Red de Semillas Libres de Colombia, it was obvious that, whereas all its members had appropriated the same set of tactics and were mobilised by a common sense of agency and a shared identity, the diagnostic made by NGOs differed and was prioritised over that of the traditional communities. All this confirms the conclusion that processes of tactic appropriation are shaped by hierarchies among and within framing tasks of a collective action frame because it is the relative potency of a framing task that leads the process of appropriation.

My examination was, nonetheless, focused on the phenomenon of ‘tactics rebounding’. This phenomenon has consequences for the collective action of Red de Semillas. Because of the relative potency that globalised tactics gave to the prognosis, the collective action of the movement has neglected the current local/particular bundles of threats identified by the traditional communities. Those threats can be even more pervasive and harmful than the ones globalised repertoires seek to challenge. Nonetheless, hierarchies may limit the development of more adequate techniques to respond to those subordinated threats.

The findings presented here are, nonetheless, limited in temporary terms. By the time I concluded my fieldwork, the NGOs were starting to notice the disconnect between the techniques of contention they implemented and the most important challenges that traditional communities faced. This means that this article may no longer accurately describe the reality of Red de Semillas. If the tactics implemented by Red de Semillas have indeed changed, it would be worthwhile to investigate the processes by which a social movement (in this case Red de Semillas) refines or modifies the criteria for the selection of tactics, and the actors and their means that induced such change.

Correspondence: Dr David Rodríguez Goyes, Department of Criminology and Sociology of Law, Faculty of Law, University of Oslo, St Olavs plass 5 NO-0130 Oslo, Norway. Email: d.r.goyes@jus.uio.no

Bastidas DA (2013) Mindala y Shagra. Guía técnica. Nariño, Colombia: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Benford R and Snow D (2000) Framing processes and social movements: An overview and assesment. Annual Review of Sociology 26: 611-639.

Bonneuil C and Thomas F (2009) Genes, Power And Profits: Public Research and Mendel Knowledge Production Regimes on GMO. Versailles, Francs: Éditions QUAE, INRA.

Borlaug N (1968) Wheat breeding and its impact on world food supply. In Finlay KW and Shephard KW (eds) Proceedings of the 3rd International Wheat Genetic Symposium: 1-36. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory: Australian Academy of Science.

Claeys P (2014) Vía Campesina’s struggle for the right to food sovereignty: From above or from below. In Lambek N, Claeys P, Wong A and Bilmayer L (eds) Rethinking Food Systems: 29-52. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer.

Crossley N (2002) Repertoires of contention and tactical diversity in the UK Psychiatric Survivors Movement: The question of appropriation. Social Movement Studies 1(1): 47-71. DOI: 10.1080/14742830120118891.

Desmarais AA (2007) La Vía Campesina. Globalization and the Power of Peasants. Manitoba, Canada: Ferrwood Publishing.

Domingo P and O’Neil T (2014) Overview: The Political Economy of Legal Empowerment. Legal Mobilisation Strategies and Implications for Development. London: Overseas Development Institute.

Douglas M (2005 [1966]) Purity and Danger. London: Routledge classics.

Escobar A (2016) Thinking-feeling with the Earth: Territorial struggles and the ontological dimension of the epistemologies of the South. Revista de Antropología Iberoamericana 11(1): 11-32.

Fischer J, Abson DJ, Bergsten A, French Collier N, Dorresteijn I, Hanspach J, Hylander K, Schultner J and Senbeta F (2017) Reframing the food-biodiversity challenge. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 32(5): 335-345. DOI: 10.1016/j.tree.2017.02.009.

Gamson W (1995. Constructing social protest. In Johnston H and Klandermans B (eds) Social Movements and Culture: 85-106. Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press.

Instituto Colombiano de Bienestar Familiar [Colombian Institute of Family Wellbeing] (ICBF), Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Departament Administrativo Nacional de Estadística [National Administrative Department of Statistics] (DANE) and Univerisdad de Antioquia [University of Antioquia] (UDEA) (2008) Adaptación y validación interna y externa de la escala latinoamericana y caribeña para la medición de seguridad alimentaria en el hogar -ELcsa Colombia (Informe Técnico).

Kinchy A (2010) Epistemic boomerang: Expert policy advice as leverage in the campaign against transgenic maize in Mexico. Mobilization: An International Quarterly 15(2): 179-198.

Kloppenburg J (2010) Impeding dispossession, enabling repossession: Biological open source and the recovery of seed sovereignty. Journal of Agrarian Change 10(3): 367-388. DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-0366.2010.00275.x,

Kloppenburg J (2014) Re-purposing the master’s tools: The open source seed initiative and the struggle for seed sovereignty. The Journal of Peasant Studies 41(6): 1225-1246.

Lemaitre J and Sandvik KB (2015) Shifting frames, vanishing resources, and dangerous political opportunities: Legal mobilization among displaced women in Colombia. Law & Society Review 49(1): 5-38. DOI: 10.1111/lasr.12119.

La Vía Campesina [The Peasant Way] (2011) Los pequeños porudctores están enfriando el planeta. Semillas 46/47: 25-27.

Martínez-Torres ME and Rosset PM (2010) La Vía Campesina: The birth and evolution of a transnational social movement. The Journal of Peasant Studies 37(1): 149-175.

Massal JE (2014) Revueltas, Insurrecciones y Protestas. Un Panorama de las Dinámicas de Movilización en el Sglo XXI. Bogotá, Colombia: Instituto de Estudios Políticos y Relaciones Internacionales, Universidad Nacional de Colombia [Institute of Political Studies and International Relations, National University of Colombia].

Mauss M (2000) The Gift: The Form and Reason for Exchange in Archaic Societies. London: Routledge.

Ministerio de Salud [Ministry of Health] and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2013) Documento Técnico de la Situación en Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutricional (SAN). Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social. Available at http://www.osancolombia.gov.co/doc/Documento_tecnico_situacion133220313.pdf (accessed 13 December 2017).

Moore JW (2000) Environmental crises and the metabolic rift in world-historical perspective. Organization & Environment 13(2): 123-157. DOI: 10.1177/1086026600132001.

Murphy G (2005) Coalitions and the development of the global environmental movement: A double-edged sword. Mobilization: An International Journal 10(2): 235-250.

Observatorio de Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutricional de Colombia [Colombian Observaory of Food and Nutrition Security] (OSAN) (2014) Situación alimentaria y nutricional en Colombia bajo el enfoque de determinates sociales. Boletín No.001/0214. M. d. S. y. P. Social. Bogotá, Colombia: OSAN.

Passy F and Monsch G-A (2014) Do social networks really matter in contentious politics? Social Movement Studies 13(1): 22-47. DOI: 10.1080/14742837.2013.863146.

Reimann K (2001) Building networks from the outside in: International movements, Japanese NGOs, and the Kyoto Climate Change Conference. Mobilization: An International Quarterly 6(1): 69-82.

Roggeband C (2007) Translators and transformers: International inspirations and exchange in social movements. Social Movement Studies 6(3): 245-259. DOI: 10.1080/14742830701666947.

Sandberg S (2006) Fighting neo-liberalism with neo-liberal discourse: ATTAC Norway, Foucault and collective action framing. Social Movement Studies 5(3): 209-227. DOI: 10.1080/14742830600991529.

Smith J (2001) Globalizing resistance: The Battle of Seattle and the future of social movements. Mobilization: An International Journal 6(1): 1-20.

Snow DA, Zurcher LA and Ekland-Olson S (1980) Social networks and social movements: A microstructural approach to differential recruitment. American Sociological Review 45(5): 787-801.

Tilly C (1977) Getting it together in Burgundy, 1675-1975. Theory and Society 4(4): 479-504.

Tilly C (1978) From Mobilization to Revolution. New York: McGraw Hill.

Touraine A (2002) The importance of social movements. Social Movement Studies 1(1): 89-95.

Vargas Roncancio ID (2011) Sistemas de Conocimiento Ecológico Tradicional y sus Mecannismos de Transformación: El Caso de una Chagra Amazónica. Maestría en Biodiciencias y Derecho [Unpublished Masters dissertation], Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Available at http://www.bdigital.unal.edu.co/4097/1/ivandariovargasroncancio.2011.pdf (accessed 13 December 2017).

Legislation cited

Constitution of Colombia 1991

Establishing Scientific, Technical, and Administrative Regulations for Health Research. Resolution 008430 of 1993 (Colombia).

[1] As of 2017, the Colombian hunger index was 8. By way of comparison, Chile has an index of under 5, and Russia of 6.2 (available at http://www.globalhungerindex.org/results-2017/; accessed 13 December 2017). Whereas this is a global index, the scores of countries where the prevalence of hunger is very low, such as Nordic, West European or Oceanian countries, are not calculated.

[2] I am not interested here in exploring the connections as to how these two production systems interact and conflict. The focus is, rather, on the dynamics that have shaped the tactics used by the social movement that arose from the broad conflict between these systems.

[3] The literature reviewed in this section focuses on approaches to social movements composed at least partly from the grassroots. Other movements also defend seeds but are differentiated from the subjects of this article in that they have more capital and comprise plant breeders and policy makers.

[4] The effects of political violence on the action of social movements remains to be studied in depth.

[5] More information about Red de Semillas can be found at http://www.redsemillaslibres.co/

[6] Coalition is understood here as the formal alliance that builds a larger structure by aggregating resources from existing organisations (Murphy 2005).

[7] This project has fulfilled the ethical protocols as established both in Norway and Colombia. Because I am based at the Faculty of Law, University of Oslo, I received authorisation to conduct my project from the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (code 52095). Because the fieldwork was undertaken in Colombia, this research project was revised and accepted by the expert committees of Colciencias (Department of Science, Technology and Innovation) and Universidad Antonio Nariño.

[8] Food sovereignty for communities implies the possibility of nourishment from a diversity of products freely chosen by them. According to the traditional communities, whereas food sovereignty encompasses food security, food security without sovereignty creates a situation of dependency on monocultures that reduces dietary variety.

[9] For the importance of exchange in the creation and strengthening of social fabric in communities, see Mauss (2000).

[10] For information about SWISSAID, see https://www.swissaid.ch/en (accessed 13 December 2017).

[11] Revista Semillas is available at http://www.semillas.org.co/es/revista (accessed 13 December 2017).

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/IntJlCrimJustSocDem/2018/7.html