|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy |

Victoria Nagy

University of Tasmania, Australia

Alana Piper

University of Technology Sydney, Australia

|

Abstract

This paper examines imprisonment data from Victoria between 1860 and 1920

to gather insights into the variations in incidence of women

being convicted by

rural versus urban courts, including close focus on the difference in types of

offences being committed in urban

and rural locations. This paper also details

women’s mobility between both communities as well as change in their

offending

profiles based on their geographic locations. Our findings suggest

that while the authorities were broadly most concerned with removing

disorderly

and vagrant women from both urban and rural streets, rural offending had its own

characteristics that differentiate it

from urban offending. Therefore, this

demonstrates that when examining female offending, geographic location of an

offender and offence

must be taken into consideration.

Keywords

Rural crime; female offending; history; Victoria; imprisonment.

|

Nagy V and Piper A (2019) Imprisonment of female urban and rural offenders in Victoria, 1860–1920. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 8(1): 100-115. DOI: 10.5204/ijcjsd.v8i1.941.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence. As an open access journal, articles are free to use with proper attribution. ISSN: 2202-8005

Criminologists have traditionally focused their attention on crime in the urban environment, not only in Australian literature but also internationally (Carrington 2007; DeKeseredy 2015). This is not without validity, as a large proportion of crime is recorded within dense urban populations. Concern with the urban environment and its perceived criminogenic properties have been the focus of social scientists since the major move from agrarian to more industrialised societies. The consequent population shift from rural to urban environments was problematised and located as the cause for changes in suicide rates, interpersonal conflict, property damage and general social malaise (Durkheim 1895/2007; Tönnies 1957; Wirth 1938).

In the last three decades, there has been a growth in scholarship examining crime in rural communities, including criminogenic risk factors for offending and victimisation. Recent exploration of crime and policing in rural Australia highlights the very different issues that these communities in Australia face in comparison to their international counterparts. The literature has also argued that the bucolic image of regional and rural Australia as a place of peace, tranquillity and safety is not based on reality, with rural communities often facing similar crime rates and issues as urban environments (Carcach 2000; Carrington 2007; Hogg and Carrington 2006; Jobes et al. 2000). Since the 1980s, attempts have been made to deliver historical, long-term quantitative data of both urban and rural convictions by researchers but with little analysis of gender differences, nor contextualisation of the statistical data (Mukherjee, Walker and Jacobsen 1986). Research into historical crimes in rural Australia has also tended to focus on bushranging (with particular focus on Ned Kelly and the Kelly Gang), policing and unrest on the goldfields or issues with squatters (Disher 1981; McQuilton 1987; Thurgood 1988). This focus has arguably wrought a distinctive male focus in the research so far. As such, this article begins to redress this imbalance in contemporary and historical criminology knowledge by examining urban and rural women’s imprisonment in Victoria between 1860 and 1920.

This article examines the offending patterns of 6,042 women imprisoned for the first time in the Australian state of Victoria between 1860 and 1920; of this group geographic data is noted for 6,027 prisoners. This dataset represents the first longitudinal study of women’s criminality in Australia and one of the largest studies of historic female offending to date. It enables insights into the variations in incidence of women being convicted by rural versus urban courts, including close focus on the difference in types of offences being committed in urban and rural locations. Further, it details women’s mobility between both communities as well as change in their offending profiles based on their geographic locations. Our findings suggest that while the authorities were broadly most concerned with removing disorderly and vagrant women from both urban and rural streets, rural offending had its own characteristics that differentiate it from urban offending. Therefore, this demonstrates that when examining female offending, geographic location of an offender and offence must be taken into consideration.

Defining what is considered ‘rural’ or ‘regional’ is difficult. This is due in part to definitions of rurality changing based on the discipline of investigators, as well as traditional Australian notions of regional and rural as being anything that is outside the major coastal capital cities (DeKeseredy 2015; Hogg and Carrington 2006). For the purposes of this study, Melbourne is the urban location against which ‘rural’ data are being compared. Melbourne grew exponentially during the nineteenth century and towns that were once on the periphery and not part of greater Melbourne in the 1860s became suburbs by 1920. For example, Dandenong was not considered part of Melbourne until after the postwar period but was an important rural township during the latter part of the nineteenth century when it acted as the gateway between the Gippsland region and the city of Melbourne. For this reason and simplicity’s sake, this article will use metropolitan Melbourne boundaries from 1900 to delineate the urban region. Larger settlements outside of Melbourne—those that could be classified as regional centres—will also be classed as rural rather than urban because despite having slightly denser populations than other rural townships, their demographics and socio-legal methods were more akin to rural rather than urban environments.

Unsurprisingly, crime has been, both in the past and present, associated predominantly with men as offenders, with feminist criminology itself tending to focus on the dynamic of crime with men as offenders and women as victims (Carrington 2013; Covington and Bloom 2003; Mazerolle 2008). Contemporary criminological research into gender, crime and rural Australia has identified violence and criminal offending as driven in part by narrow definitions of masculinity in rural locations (Carrington 2007). Research into historical instances of rural criminality and violence in Australia has overwhelmingly focused on individual cases, favouring emphasis on men’s offending over women’s (Highland 1994; Phillips 1994). Yet, historically, in Australia and internationally, women and girls were often involved with antisocial and criminal behaviour in both urban and rural environments at much higher rates than those recorded today (D’Cruze 2000; Nagy 2015). The contemporary oversight of women’s and girls’ historical involvement with the criminal justice system as offenders has led to a skewed understanding as to where they in Australia fit in the criminal justice system, as well as a lack of awareness of the potential sources of twentieth- and early twenty-first centuries’ women’s increased offending rates.

Towards the end of the nineteenth century more women were imprisoned in Victorian jails on a day-to-day basis than any other Australian colony (Ross and Skondreas 2000). Women were routinely imprisoned in colonial Victoria for a range of offences ranging from petty (e.g., indecent language in public) to serious crimes, such as murder. Historical research into female offending in Victoria has typically concentrated on those crimes perceived to be most heavily gendered, particularly sex work and reproduction-related offences (Finch and Stratton 1988; Frances 2007; Goc 2013; Laster 1989; McConville 1980; Rychner 2017). The former has been described as being located most heavily within Melbourne or on the goldfields, while the latter—that is, abortion—has typically been depicted as a mostly urban crime, with rural women travelling to the city to procure the service. Likewise, infanticide, though recognised as not being restricted to the city, has been described as particularly associated with the urban context (Swain and Howe 1995: 91). Another focus in historical scholarship has been female murderers subjected to capital punishment (Cannon 1994; Laster 1994; Overington 2014), with little focus on spatial location. Research into more general patterns of female offending in Victoria during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries has only recently started to emerge, with analyses on risk factors for women’s imprisonment, as well as offence variation in women’s criminal careers (Piper and Nagy 2017, 2018). Therefore, this paper represents an important contribution to the historical and criminological literature, which have seldom explored the relationship between female offending and geographic location.

As with other parts of the Western world, there has always been a dichotomy between the urban and rural environments in Australia. Life outside the city was often considered to be, if not exactly idyllic, at least more morally uplifting than the polluted slums of the urban landscape. Moral welfare societies in Victoria mirrored their overseas counterparts in advocating the removal of fallen women and delinquent children to rural situations and institutions where they might have the best chance to reform (Finnane 1997: 76–77). At the same time, the bush was popularly imagined as a harsh and dangerous landscape, especially for women—although, one that could also offer greater freedoms (James 1989; Murphy 2010). Australian art, literature and culture have imagined the female bush dweller to be more akin to her rural male counterpart (rugged, egalitarian and independent; e.g., as portrayed in Henry Lawson’s The Drover’s Wife) than to urban women. While the reality of such depictions remains debatable, colonial women living in rural Victoria were subject to far different conditions and concerns than their counterparts in Melbourne.

For a large portion of the nineteenth century, men outnumbered women in Victoria. In the 1861 census, there were 153.6 men for 100 women in a colony that had a total population of 540,322 individuals. However, Melbourne did not suffer from this disparity, with many suburbs or municipalities having a higher female than male population. Geelong, Victoria’s second most populous area, also had more women than men listed in the census, but not by a significant margin (11,834 women to 11,125 men). Instead, it was in the mining districts (such as Ballarat and Bendigo)—where 42% of the colony’s population resided—that contributed to the sex ratio difference, with 154,692 male inhabitants to only 73,489 women. By the 1881 census there was more parity between the number of women and men being recorded around Victoria, with nearly 91 women to 100 men, which was on par with the other Australasian colonies. Women outnumbered men in Melbourne and its urban municipalities (220,843 women to 213,624 men), and were beginning to dominate not only in Geelong but also in the central area of Ballarat. By 1901 there was almost complete parity between the sexes; with 98.94 women to 100 men, women began outnumbering men not only in Melbourne but in almost every large town in rural Victoria. By 1920 the difference between urban and rural Victoria’s population was negligible; that is, 763,000 called Melbourne home while 764,999 lived in rural Victoria (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS] 2014). Table 1 outlines the comparative female populations of Melbourne and rural Victoria.

Table 1: Urban and rural female population

|

|

Melbourne and suburban female population

|

Victorian female population (excluding Melbourne and

suburbs)

|

|

1861

|

30,935

|

180,736

|

|

1871

|

116,631

|

213,847

|

|

1881

|

220,843

|

410,263

|

|

1891

|

242,936

|

299,055

|

|

1901

|

260,876

|

336,582

|

|

1911

|

311,015

|

348,945

|

|

1921

|

407,025

|

368,790

|

In addition to being distributed differently across the urban and rural environments, women in Victoria faced different socio-economic conditions dependent on their location; although, some factors were shared. For example, the 1871 census notes that only 20% of women in Victoria had a form of employment that was not domestic duties associated with being a wife or daughter, nor were they under the care of the state. Women as a group had fewer legitimate means of earning a wage than men, but those in rural areas faced even more limited employment prospects, with scarcer opportunities in the manufacturing and retail industries than in the city, as well as limited availability of labour in the hospitality industry around the goldfields (Kingston 1975). Factors affecting the number of such positions being offered—such as the economic depression of the 1890s or the absence of male workers on military service during World War I—may have had a particular effect on the lives of urban working-class women (Frances 1993).

Marriage trends were also likely to affect women’s socio-economic position and resulting criminality. In the 1881 census, a trend was noted throughout the colony where there were more wives than husbands. Such disparity would indicate that the missing husbands were either residing outside the colony, claiming they were unmarried or were otherwise absent from the lives of many Victorian women. Wife desertion was certainly common and was lamented by authorities as a cause of female crime and ‘immorality’ (Twomey 2002). Conversely, the high marriage rates among women in rural areas that resulted from the sex imbalance in many of those regions was liable to have had a reducing effect on female crime within those environments, given the historical correlation between female offending and lack of a male provider (Piper 2015).

The dataset used in this analysis is drawn from the Central Register of Female Prisoners, a series of records created by Victoria’s penal department to register prisoners’ names, personal details and convictions. Upon a woman’s first entry to prison a record was created for her that would be added onto any subsequent returns (minor or prior convictions that had not resulted in imprisonment were also usually noted). The format of the record-keeping system remained consistent across several decades and included the following details: biographical information such as birthplace, year of birth, year of arrival in Victoria (if a migrant), religion, occupation, literacy and marital status; conviction details including trial date, offence, court and sentence; descriptions of women’s appearances including height, weight, tattoos and physical conditions, as well as mugshots, which began appearing in the late nineteenth century; and occasionally other comments about a woman’s family history, their behaviour inside prison and details of their release or transfers to other institutions, such as charity homes or ‘lunatic’ asylums.

This register provides a sample of 6,042 individual women who first entered the central prison system between 1860 and 1920. It does not include the women incarcerated in Victoria’s prisons during this period who had been imprisoned prior to 1860, as their records exist in earlier registers. However, three women in the sample had convictions that occurred prior to 1860, the earliest occurring in 1854 but as they were not imprisoned at that time they did not have prison records. There were also 124 women in the dataset who continued offending after 1920, the last known conviction occurring in 1947. While the information contained in this data is rich, its limitations should also be noted: biographic information such as occupation and marital status were recorded upon women’s first imprisonment but were seldom updated on subsequent returns, and women may have purposively misled officials when asked to supply details about their background. This latter point manifested in aliases, and court registrars and prison officials were generally very aware of the propensity for this and could effectively record and link aliases to existing prison records. Recidivism levels may also be somewhat underestimated due to officials’ occasionally lax approach to noting details of minor convictions that had not resulted in imprisonment.

Information about geographic location has been obtained from the prisoner records through the listed courts where women were tried and convicted. There were three levels of court one could find themselves: Court of Petty Sessions, Court of General Sessions and the Supreme Court. The Court of Petty Sessions (sometimes also referred to as Police Courts) was the lowest court and initially dealt almost solely with minor criminal matters such as drunkenness, vagrancy and the most trivial class of larcenies and assaults. These small courts were located all over Victoria, meaning that the Petty Sessions Court hearing a matter was almost always located very close to where the crime itself occurred. The Court of General Sessions (established in 1852) was a midpoint between the Court of Petty Sessions and the Supreme Court, empowered to try cases of non-capital crimes before juries. The Court of General Sessions was initially only established in Melbourne and Geelong, but was later introduced to other areas such as Ballarat. Finally, the highest court in Victoria was the Supreme Court, which heard matters not only in Melbourne but also from beyond the city. As with the system in England, Supreme Court judges would attend Circuit Courts in rural locations such as Ballarat, Bendigo and Geelong, as well as Beechworth, Ararat, Castlemaine, Maryborough and Sale to hear cases of serious crimes. Women charged with more serious offences would generally be committed to the General Sessions or Circuit Court Sessions located closest to where their crime took place, but this could be some distance if they were living remotely to any of the major centres. However, the vast bulk of female offending was heard by the more proximate Petty Sessions, with more than 80% of female prisoners only ever tried in this jurisdiction over the course of their criminal careers (Piper and Nagy 2017); this mirrors contemporary findings about women’s offending and their appearances in Magistrates’ courts on minor charges.

Overall, the offence profiles of female prisoners in Victoria between 1860 and 1920 were similar to results from other research in Australia and abroad for roughly the same period (Allen 1990; Zedner 1991). The bulk of female offending was weighted towards minor public order offences such as vagrancy and disorderly conduct, while theft offences greatly predominated over violent crimes when it came to more serious criminal activity (Piper and Nagy 2017). This pattern is broadly evident across women imprisoned by both urban and rural courts. However, when more specific offence types are examined some interesting divergences become apparent.

The prison registers identify 6,042 unique female offenders in the period of 1860 to 1920, of whom 6,027 have location data recorded for the court that had first sentenced them to imprisonment. The data suggest that for around three-quarters of female prisoners this was also their first conviction overall, an indication of a lack of sentencing alternatives in this period beyond the use of fines that some women found themselves unable to pay due to poverty (Finnane 1997: 33–35). Of these 6,027 women, 73.3% were sentenced from a court located in the greater Melbourne area (see Table 2).

Table 2: Type of offence for women first imprisoned against location of court where convictions occurred

|

Offence

|

Number

|

Urban court %

|

Rural court %

|

|

Larceny offences

|

822

|

71.4

|

28.6

|

|

Receiving stolen goods

|

116

|

76.7

|

23.3

|

|

Larceny from the person

|

105

|

82.9

|

17.1

|

|

Fraud offences

|

98

|

64.3

|

35.7

|

|

Robbery

|

34

|

85.3

|

14.7

|

|

Burglary

|

22

|

77.3

|

22.7

|

|

Stock offences

|

13

|

46.2

|

53.8

|

|

Threatening life or to cause harm

|

262

|

84.7

|

15.3

|

|

Assault or wounding

|

176

|

69.9

|

30.1

|

|

Murder or manslaughter

|

80

|

68.8

|

31.3

|

|

Vagrancy, begging or lacking lawful means of support

|

2,072

|

77.2

|

22.8

|

|

Disorderly, indecent or riotous conduct

|

1,220

|

77

|

23

|

|

Drunkenness offences

|

311

|

61.4

|

38.6

|

|

Sex work related offences

|

168

|

61.3

|

38.7

|

|

Obscene, indecent or abusive language

|

139

|

50.4

|

49.6

|

|

Consorting with, being or keeping a house frequented by thieves or

suspected persons

|

71

|

56.3

|

43.7

|

|

Offences against justice or courts

|

43

|

60.5

|

39.5

|

|

Damaging property

|

40

|

70

|

30

|

|

Offences involving care of children

|

36

|

75

|

25

|

|

Concealment of birth

|

35

|

37.1

|

62.9

|

|

Arson

|

33

|

45.5

|

54.5

|

|

Intent to commit or aiding and abetting felony

|

22

|

81.8

|

18.2

|

|

Suicide threatened or attempted

|

19

|

68.4

|

31.6

|

|

Illegally selling liquor

|

17

|

35.3

|

64.7

|

|

Abortion

|

11

|

81.8

|

18.2

|

|

Bigamy

|

9

|

77.8

|

22.2

|

|

Miscellaneous offences

|

44

|

61.4

|

38.6

|

|

Unknown

|

9

|

77.8

|

22.2

|

|

Total

|

6,027

|

73.3

|

26.7

|

|

Five cells (8.9%) have expected count less than 5. 2

(27) = 203, p < 0.001.

|

|||

Even allowing for the disproportionate concentration of Victoria’s female population in the capital during the colonial period, this figure suggests that urban women were over-represented in the prisoner population. Although Melbourne’s female population accounted for only 44.8% of the female population of Victoria in 1881, Melbourne courts contributed over 78% of female prisoners. This supports contemporary research about the criminogenic properties of cities and the effect that urban disadvantage and poor living conditions have on the creation of illicit economies and behaviours (Schwartz and Gertseva 2010). It also supports characterisations of Melbourne as a cesspool of crime by nineteenth-century commentators (Davison and Dunstan 1985).

Many of the offences where urban women were particularly over-represented seem to confirm Melbourne’s possession of an underworld economy (see Table 2). While urban courts accounted for 73.3% of first-time female prisoners overall, this proportion rose higher when it came to many theft offences including robbery (85.3%), larceny from the person (82.9%), burglary (77.3%) and receiving stolen goods (76.7%). Urban rather than rural women would also find themselves imprisoned at higher rates for aiding and abetting or intent to commit a felony (81.8% to the rural 18.2%). This aligns with contemporary findings that show it is property crime that most ‘closely approximates the conventional wisdom that crime rates tend to increase with population size and concentration’ (Carrington 2007: 33). The colonial city probably provided greater criminal opportunities for certain types of theft than rural areas. For example, robbery and larceny from the person by female offenders was predominantly committed within the context of sex work (Piper 2018), which, while not confined to the capital, was particularly prevalent there (Frances 2007). It is also possible that, as Hogg and Carrington (2006: 120–121) discovered in the modern context, there was a lower detection (and consequently imprisonment) rate for property offences in rural locations, especially for crimes such as break-ins, as police were often reliant in this period on eyewitness accounts by neighbours or passing foot traffic. Closer proximity to neighbours in urban areas may have also led to higher reporting levels of other types of crimes such as threatening life or to cause harm, with 84.7% of women imprisoned for this offence tried by Melbourne courts. Large differences in rates between urban and rural offenders for some other offences, such as suicide (threatened or attempted), might also have been due to closer proximity to neighbours who were in a position to intervene in and report attempts at suicide in Melbourne versus in rural communities.

The public nature of working-class life in colonial Melbourne and its possession of a street subculture may have likewise influenced the slightly elevated proportions of urban women first imprisoned for vagrancy (77.2%) or disorderly conduct offences (77%). These offences were routinely used to police female sex workers (Frances 2007) and appear to have been deployed in this capacity far more often than specific sex work related offences (such as soliciting or brothel-keeping), for which urban women were less strongly represented in the dataset. Additionally, homelessness, as today, was also a genuine problem, with colonial commentators observing that Melbourne was inhabited by high numbers of female beggars, most of which were concentrated among the very young and very old but could be found resident in the city year after year (Freeman 1888: 133). Contrariwise, Julie Kimber (2010) has suggested that in rural towns in Australia vagrancy charges were historically used as a means of moving ‘problem’ women (notably drunkards or sex workers) on to other areas.

Yet, while women of Melbourne’s criminal underclass contributed disproportionately to offending overall, there were also particular offences for which elevated proportions of female prisoners had been sentenced by rural courts. Whereas only 26.7% of the total female prisoner sample had first been sentenced by courts outside Melbourne, their numbers rose significantly for those entering prison for the following crimes: illegally selling liquor (64.7%); concealment of birth (62.9%); stock offences (53.8%); arson (54.5%); obscene, indecent or abusive language (49.6%); consorting, being or keeping house frequented by thieves or suspected persons (43.7%); offences against justice (39.5%); sex work related offences (38.7%); drunkenness (38.6%); fraud offences (35.7%); suicide (31.6%); murder or manslaughter (31.3%); assault or wounding (30.1%); and damaging property (30%).

Some of these offences speak to the particular criminal opportunities of rural environments. For example, the crime with the highest proportion of rural offenders (selling illegal liquor) was an understandable occurrence in remote areas with fewer established hotels. Perceptions of hospitality and food preparation as being feminine qualities and pursuits meant many women in colonial Victoria were able to find employment in either legitimate hotel-keeping (Wright 2003), or, like bushranger Ned Kelly’s mother Ellen, in more illicit sly-grog selling (Lake 1985). Sly-grog shanties were particularly common on the goldfields, with diarist Samuel Curtis Candler (1848–19: 126) recounting an anecdote in the late 1860s about a particularly colourful character who used to go around the diggings with a two-gallon tin rum tank disguised under her dress as a pregnancy belly.

Likewise, while many forms of theft were linked to the urban centre, it makes sense that stock offences would be concentrated more in rural locations where there were more cattle, sheep, horses and other animals to steal—although, the low number of women convicted overall of this predominantly male-perpetrated offence means that from a frequency rather than a proportional perspective there was little difference between urban and rural offending rates among women. The increased proportion of rural women among those imprisoned for fraud offences presents more of a puzzle. This was possibly connected to a greater willingness among rural business owners to cash cheques or provide goods on credit, inevitably creating opportunities for some individuals to present forgeries or obtain items under false pretences. Conversely, the less anonymous nature of smaller towns perhaps meant people who practised such deceptions simply found it less easy to evade detection.

Lack of anonymity in rural areas also likely increased both the reputational threat posed by deviant behaviour and the likelihood that such behaviour would ultimately be uncovered. This would explain why rural women accounted for the majority of those imprisoned for concealment of birth, a charge usually brought against women who had failed to register the births of illegitimate children (Goc 2013: 3). Indeed, this often acted as an alternative charge to infanticide when women alleged a child had been stillborn. Other forms of female deviance, such as drunkenness and obscene language, may have also been less tolerated in close-knit regional centres, which were structured around institutions and symbols of civil and moral authority in an effort to curb the ‘loose’ behaviour associated with the rough-and-tumble settlements on the colonial margins. Women within rural communities may have also been less able to pay the fines usually offered as alternatives to imprisonment in relation to such offences, either because their support networks were not as extensive as urban women or because there were less independent economic opportunities.

The need to enforce order onto the chaos of the frontier also potentially influenced the policing of interpersonal violence, at least around non-fatal assaults. Police in rural Victoria were different to their urban counterparts, with a more paramilitary model being employed outside Melbourne; the law was also upheld in a very selective fashion by rural Victorian police (McQuilton 1987). This did not translate into an increased imprisonment of non-white women in the way that it sometimes did for non-white men. Only four female prisoners in the sample were identified as Indigenous; however, some others may have also had Aboriginal heritage (Piper and Nagy 2018). As Grant (2014) has explored, few Indigenous women were jailed during this period unlike Indigenous men.

However, it is noticeable that the imprisonment rate of rural women for both assaults and homicide—a crime unlikely to be subject to selective policing—was higher than the general imprisonment of rural women (but still under-represented compared to the overall female population). More contemporary studies have found that women’s violence is strongly driven by rates of male violence in rural environments (Parker and Reckdenwald 2008). Some of the factors suggested by recent scholarship as contributing to violence in modern rural areas—such as isolation, heavy-drinking cultures and more limited access to support services—are likely to have also been relevant historically (Hogg and Carrington 2006: 65; Jobes et al. 2001). These would presumably act as additional risk factors for other types of crimes with stronger associations with rural areas in the sample, such as suicide, arson and property damage.

While the broad patterns of female offending were fairly similar across urban and rural locations, an examination of the specific offences that resulted in women’s entry into the prison system reveals considerable variation produced by environmental conditions. Beyond this, location also influenced women’s offending patterns across time.

Over the course of one’s criminal careers, a significant proportion of female offenders would commit different types of offences (Piper and Nagy 2017). Overall, the majority of women’s offending, considering all convictions, still comprised of public order offences, followed by theft offences, then violent and other types of crimes (Table 2). As with first offence data, factoring in location produced some significant trends. For example, rural women still showed a particular likelihood to be convicted of crimes that fell in the ‘other’ offences category, such as arson, attempted suicide and concealment of birth. Conversely, urban offenders make a greater showing among violent offenders when looking across criminal careers; although, this may be the case because this broad category includes more minor forms of violence, such as threatening behaviour.

In addition to engaging in different criminal activities, across time female prisoners were also liable to commit offences in different locations (see Table 3).

Table 3: Offence participation rates among female urban, rural and mobile offenders

|

Offence category *

|

No. of female prisoners

|

Urban offenders %

|

Rural offenders %

|

Mobile offenders %

|

|

Public order offences a

|

4,456

|

70.8

|

23.4

|

5.7

|

|

Theft offences b

|

1,738

|

71

|

22.6

|

6.4

|

|

Violent offences c

|

778

|

74.7

|

21.6

|

3.7

|

|

Other offences d

|

676

|

66.6

|

28.1

|

5.3

|

|

All prisoners

|

6,027

|

70.6

|

24.9

|

4.5

|

|

* Offence categories are not mutually exclusive, as a prisoner could commit

more than one type of offence over her criminal career.

a 2 (2) = 67.83, p

< 0.001

b 2 (2) = 23.59, p

< 0.001

c 2 (2) = 7.18, p

< 0.05

d 2 (2) = 6.07, p

< 0.05

|

||||

In all, 4.5% of the 6,027 female prisoners in the sample amassed convictions in courts both inside and outside of Melbourne. These mobile offenders made a particularly strong showing among those who had at least one conviction for theft at some point (6.4%), but were under-represented among those with a conviction for violence (3.7%). Perhaps, given that female violence has been routinely linked to the context of close interpersonal relations (Schwartz and Gertseva 2010), it was more likely to take place among those embedded in permanent, ongoing networks. Meanwhile, the risks associated with identification in theft cases perhaps in itself acted as an inducement to mobility among such offenders, encouraging known criminals to move to new areas where their face and modus operandi were less known. In discussion of the history of property crime in London, William Meier (2011: 41–66) notes that the increased mobility enabled by new systems of transportation meant that the ‘traveling thief’ was one of the major challenges faced by law enforcement across the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

It was not only the type of offending that differed between urban, rural and mobile offenders, but also one’s overall level of offending. The average mean time between women’s first- and last-known convictions was shorter for rural offenders (M = 1,018 days, SD = 2,084) than their urban counterparts (M = 1,305 days, SD = 2,343); however, both were far exceeded by the average criminal career of mobile offenders (M = 4,638 days, SD = 3,852). There was a similar trend in terms of number of convictions. While metropolitan offenders had a mean average of four convictions (SD = 7) to rural offenders’ mean of three (SD = 5), the prolific recidivism of mobile offenders resulted in an average of 12 convictions (SD = 14).

These findings align with research strongly associating mobility with higher levels of offending (Barnett and Mencken 2002; Steffensmeier and Haynie 2000). Similarly, Clinard (1942) in their study of youth mobility between rural and urban environments discovered that young populations who were exposed to urban values and returned to rural communities exhibited criminal offending typologies more often associated with urban offenders. Brown (2011) also found such patterns when examining the conviction histories of a sample of 427 men imprisoned at Dartmoor in England in 1932. Brown’s sample reported a much higher rate of mobility overall than that found in the Victorian female sample; however, this is probably due to differences in definitions and sampling techniques. Our designation of mobile offenders only takes into account mobility between urban and rural contexts (but potentially hides mobility across different rural contexts) or between a variety of Melbourne suburbs. Further, while our sample looks at prisoners across the whole of Victoria, Brown (2011) examined a prison that housed mostly serial offenders; thus, if recidivist offenders were more mobile, it would make sense that such a sample showed a high rate of mobility. The gender differences between the samples are also likely important, given that men historically were prone to live more mobile lives than women as a result of movement connected to the pursuit of employment (Lake 1986). The differences perhaps also point to the possibility that levels of mobility shifted across sociohistoric context, with Brown (2011: 561) underlining the significance to her study of motor-car theft in the interwar period, a factor not present in our 1860–1920 sample.

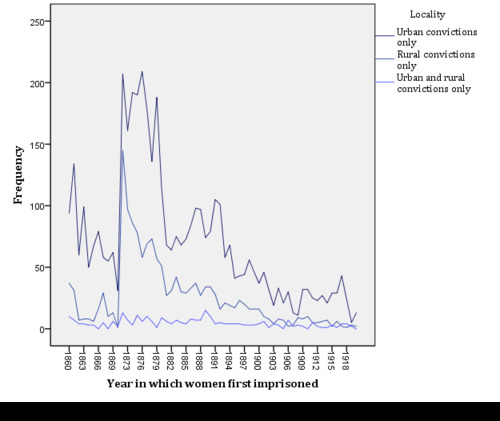

Changing conditions over time also likely resulted in changing numbers of rural, urban and mobile offenders within the 1860–1920 sample itself. Analysis of the number of women entering the prison system each year against the location of the courts in which they were convicted across their criminal careers reveals no single, consistent trend, but rather a number of significant fluctuations in the proportion of rural, urban and mobile (urban and rural convictions) women (Figure 1).

For example, whereas almost four-fifths of women imprisoned in the 1860s would only ever be convicted in Melbourne courts, this rate fell considerably to around two-thirds of women entering the system in the 1870s and 1880s. The successive decades—which saw a decline in the overall number of women being imprisoned—then brought a progressive rise in the proportion of those women whose convictions were urban based. The proportion of mobile offenders also rose during the early 1900s. Perhaps, then, rural women disproportionately benefitted from changes in sentencing practices—such as the release of first-time offenders on probation—that saw fewer women entering the prison system overall (White 1979).

Figure 1: Year of women’s first imprisonment between 1860 and 1920

Some of the variations in offending patterns outlined above may also be linked to differences evident in the personal characteristics of urban, rural and mobile offenders. Statistically, concentration of most criminal offending is in the adolescent and early adult periods in Australia (ABS 2017); however, this trend shifts in the historic female prisoners’ dataset. Whereas modern research suggests the teens and early twenties as peak offending periods, with a median age of 28 years, for Victoria’s female prisoners in this era it was their twenties and thirties, with a median age of first-time entry into prison being 32 years. However, age profiles shifted significantly when compared against the locations where women were convicted (Table 4).

Urban offenders tended to be younger (MED = 30 years, SD = 10) than rural (MED = 35 years, SD = 13) or mobile offenders (MED = 32 years, SD = 13) at first conviction. This means that early onset of offending may, in turn, have led to increased levels of offending persisting over one’s life, which is most evident among urban offenders when compared to their rural counterparts. Consequently, this may explain why urban offenders were particularly likely to be listed as having never been married on their initial entry to the prison system (Table 4).

Conversely, rural women accounted for an increased proportion of those first convicted after 30 years of age and whose last conviction did not take place until they were over 50 years old; this includes women who were widowed on first entry to gaol (see Table 4). This may indicate a particular ‘problem’ group of older women in rural or regional communities who in the absence of strong familial bonds—and perhaps with declining employment prospects—found themselves cast on the support of the justice system. The elevated proportions of rural women imprisoned for drunkenness and indecent language may indicate that these were the primary ways such women were policed, or that such behaviours became more common among rural women with age and the removal of social controls exerted by patriarchal figures.

Table 4: Background characteristics of urban, rural and mobile offenders

|

Variable

|

Characteristic

|

No. of female prisoners

|

Urban offenders %

|

Rural offenders %

|

Mobile offenders %

|

|

|

Age range at first conviction a

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

<= 18 years

|

589

|

77.2

|

19.7

|

3.1

|

|

|

|

19–30 years

|

2,395

|

76

|

19.4

|

4.6

|

|

|

|

> 30 years

|

3,008

|

64.9

|

30.2

|

4.9

|

|

|

Age range at last conviction b

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

< 30 years

|

2,109

|

77.1

|

21.1

|

1.8

|

|

|

|

30–49 years

|

2,811

|

69.9

|

26

|

4.1

|

|

|

|

>= 50 years

|

1,072

|

59.4

|

29.4

|

11.2

|

|

|

Marital status c

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

Married

|

1,304

|

59.7

|

26.2

|

4.1

|

|

|

|

Never married

|

638

|

75.4

|

18

|

6.6

|

|

|

|

Widowed

|

368

|

58.2

|

35.6

|

6.3

|

|

|

|

Divorced

|

4

|

100

|

0

|

0

|

|

|

Literacy d

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

Illiterate or limited literacy

|

2,121

|

72.5

|

23.3

|

4.2

|

|

|

|

Literate

|

3,818

|

69.9

|

25.5

|

4.6

|

|

|

Place born e

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

Victoria

|

1,674

|

70.6

|

24.7

|

4.7

|

|

|

|

Elsewhere Australia or New Zealand

|

734

|

78.3

|

17.2

|

4.5

|

|

|

|

Great Britain

|

3,431

|

68.8

|

26.7

|

4.5

|

|

|

|

Elsewhere overseas

|

149

|

74.5

|

20.1

|

5.4

|

|

|

Occupation f

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

Servant

|

3,804

|

73.5

|

21.7

|

4.8

|

|

|

|

Other working-class occupation

|

925

|

77.4

|

18.1

|

4.5

|

|

|

|

Household duties

|

258

|

3.5

|

92.6

|

3.9

|

|

|

|

Middle-class occupation

|

111

|

80.2

|

14.4

|

5.4

|

|

|

Mental and physical condition g

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

No disability noted

|

5,978

|

70.9

|

24.6

|

4.5

|

|

|

|

Disability noted

|

49

|

40.8

|

51

|

8.2

|

|

|

All prisoners

|

6,027

|

70.6

|

24.9

|

4.5

|

||

a 2 (4) = 100.54, p < 0.001

b 2 (4) = 195.33, p < 0.001

c 2 (6) = 47.29, p < 0.001

d 2 (2) = 4.67, p > 0.05

e 2 (6) = 31.9, p < 0.001

f 2 (6) = 699.67, p < 0.001

g 2 (2) = 21.26, p < 0.001

Fewer social welfare resources in rural areas may have presented a pathway to imprisonment for women outside Melbourne. Notations about women’s physical appearances and health upon their first entry to the prison system indicate that at least 49 women were suffering from either a physical disability (including blindness, deafness or missing limbs) or reduced mental powers, with prison officials making notations such as ‘weak intellect’ or ‘imbecile’. Over half of these disabled prisoners were rural offenders.

Occupation data taken from women on first imprisonment indicate that overall most women, both urban and rural, came from working-class backgrounds, with the vast bulk listing their occupation as servant. However, almost all those whose listed occupation indicated that they were employed in domestic duties within their own home came from rural areas, perhaps indicating the higher levels of employment of women outside the home in urban areas. Likewise, most of those engaged in more middle-class occupations—such as nursing, teaching, journalism, acting or shop-keeping—were urban offenders.

Surprisingly, one socio-economic indicator that did not vary much by location was literacy level. Despite concerns expressed during the late nineteenth century about education levels in some parts of regional Victoria (Barcan 1980), there was no significant decline in literacy among rural offenders. Historically, those born in Australia enjoyed far higher literacy rates than those born overseas due to the early introduction of free and compulsory schooling (Lyons 2001). Migration patterns did vary across rural and urban locations, with urban offenders less likely to have migrated from Great Britain and more likely to have been born in Australia. Interestingly, mobile offenders comprised an elevated proportion of those who had migrated from places other than Great Britain, indicating that coming from a non-English speaking background may have contributed to some mobile offenders’ struggle to avoid the cycle of imprisonment, as well as showing that mobility was already a significant part of their histories. More contemporary research has found migration in conjunction with a non-English speaking background, social isolation and addiction have all contributed to an exponential rise of Vietnamese women, in particular, in Victoria’s prisons (Francis 2014).

While for a large portion of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries there were more women inhabiting rural communities in Victoria, offending was overwhelmingly located in Melbourne. Although across all spatial locations women were most likely to find themselves imprisoned for public order or theft offences, there were differences between the demographics of urban, rural and mobile offenders. Social control, or rather a lack thereof, appears to have contributed to greater rates of urban and mobile women’s offending; however, rural women could often find themselves imprisoned especially in their later years. Across all groups, offending, or rather imprisonment, was declining right through to 1920, albeit at different rates and undoubtedly for various social reasons. Urban offending consistently was the greatest contributor to women’s imprisonment rates but this should not preclude attention being paid to rural female criminality. Instead, attention could most especially be paid to not only why crime in the metropolitan environment continued to be higher than the rural one, but also to what protective factors may have contributed to rural women’s decreased risk of criminal behaviour at a time when rural regions of Victoria were known for their crime and violence. Differences between the three groups of female offenders certainly highlight the importance of not only investigating the types of offences that women may have found themselves imprisoned for, but also the geographical place from which women entered the penal system, and from where re-entry would occur in cases of recidivism. Overall, the results from this study highlight the necessity for further research and spatial analysis of women’s historic offending and imprisonment in Victoria, including, but not limited to, women’s mobility across rural communities and movement within urban environments.

Correspondence: Victoria Nagy, Lecturer in Criminology, School of Social Sciences, University of Tasmania, Churchill Avenue, Hobart, TAS, 7005. Email: vicky.nagy@utas.edu.au

References

Allen JA (1990) Sex & Secrets: Crimes Involving Australian Women Since 1880. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2014) 3105.65.001 Australian Historical Population Statistics, 2014. Released 18 September 2014. Available at http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/allprimarymainfeatures/632CDC28637CF57ECA256F1F0080EBCC?opendocument (accessed 21 January 2019).

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2017) 4519.0 Recorded Crime: Offenders 2015–16. Released 8 February 2017. Available at http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/4519.02015-16?OpenDocument (accessed 21 January 2019).

Barcan A (1980) A History of Australian Education. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Barnett C and Mencken FC (2002) Social disorganization theory and the contextual nature of crime in nonmetropolitan counties. Rural Sociology 67(3): 372–393. DOI: 10.1111/j.1549-0831.2002.tb00109.x.

Brown A (2011) Crime, criminal mobility and serial offenders in early twentieth-century Britain. Contemporary British History 25(4): 551–568. DOI: 10.1080/13619462.2011.623863.

Candler SC (1848–19) Notes About Melbourne, and Diaries (manuscript). Melbourne: State Library Victoria.

Cannon M (1994) The Woman as Murderer. Mornington: Today’s Australia Publishing.

Carcach C (2000) Size, accessibility and crime in regional Australia. Trends & issues in crime and criminal justice No. 175. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology. Available at https://aic.gov.au/publications/tandi/tandi175 (accessed 21 January 2019).

Carrington K (2007) Crime in rural and regional areas. In Barclay E, Donnermeyer JF, Scott J and Hogg R (eds) Crime in Rural Australia: 27–43. Annandale: Federation Press.

Carrington K (2013) Girls, crime and violence: Toward a feminist theory of female violence. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 2(2): 63–79. DOI: 10.5204/ijcjsd.v2i2.101.

Clinard MB (1942) The process of urbanization and criminal behaviour. American Journal of Sociology 48(2): 202-221.

Covington SS and Bloom BE (2003) Gendered justice: Women in the criminal justice system. In Bloom BE (ed.) Gendered Justice: Addressing Female Offenders: 3–24. Durham: Carolina Academic Press.

Davison G and Dunstan D (1985) ‘This moral pandemonium’: Images of low life. In Davison G, Dunstan D and McConville C (eds) The Outcasts of Melbourne: Essays in Social History: 29–57. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

D’Cruze S (ed.) (2000) Everyday Violence in Britain, 1850–1950: Gender and Class. Harlow: Pearson Education.

DeKeseredy WS (2015) New directions in feminist understandings of rural crime. Journal of Rural Studies 39: 180–187. DOI: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2014.11.002.

Disher G (1981) Wretches and Rebels. Oxford: Melbourne.

Durkheim E (2007) The rules of sociological method (1895). In Appelrouth S and Edles LD (eds) Classical and Contemporary Sociological Theory: Text and Readings: 95–102. Thousand Oaks: Pine Forge Press.

Finch L and Stratton J (1988) The Australian working class and the practice of abortion 1880–1939. Journal of Australian Studies 12(23): 45–64. DOI: 10.1080/14443058809386981.

Finnane M (1997) Punishment in Australian Society. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Frances R (1993) The Politics of Work: Gender and Labour in Victoria, 1880–1939. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Frances R (2007) Selling Sex: A Hidden History of Prostitution. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press.

Francis R (2014) Birthplace, Migration and Crime: The Australian Experience. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Freeman J (1888) Lights and Shadows of Melbourne Life. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle and Rivington.

Goc N (2013) Infanticide and the Press 1822–1922: News Narratives from England and Australia. Surrey: Ashgate.

Grant E (2014) The incarceration of Australian Aboriginal women and children. In Ashton P and Wilson JZ (eds) Silent System: Forgotten Australians and the Institutionalisation of Women and Children: 43–58. Melbourne: Australian Scholarly.

Highland G (1994) A tangle of paradoxes: Race, justice and criminal law in North Queensland 1882–1894. In Philips D and Davies SE (eds) A Nation of Rogues? Crime, Law and Punishment in Colonial Australia: 123–140. Carlton: Melbourne University Press.

Hogg R and Carrington K (2006) Policing the Rural Crisis. Sydney: Federation Press.

James K (ed.) (1989) Women in Rural Australia. St Lucia: University of Queensland Press.

Jobes PC, Barclay E and Donnermeyer JF (2000) A Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis of the Relationship between Community Cohesiveness and Rural Crime, Part 1. Armidale: The Institute for Rural Futures, University of New England.

Kimber J (2010) ‘A nuisance to the community’: Policing the vagrant woman. Journal of Australian Studies 34(3): 275–293. DOI: 10.1080/14443058.2010.498092.

Kingston B (1975) My Wife, My Daughter and Poor Mary Ann: Women and Work in Australia. Melbourne: Thomas Nelson Australia.

Lake M (1985) The trials of Ellen Kelly. In Lake M and Kelly F (eds) Double Time: Women in Victoria, 150 years: 86–95. Ringwood: Penguin.

Lake M (1986) The politics of respectability: Identifying the masculine context. Historical Studies 22(86): 116–131. DOI: 10.1080/10314618608595739.

Laster K (1989) Infanticide: A litmus test for feminist criminological theory. Australia and New Zealand Journal of Criminology 22(3): 151–166. DOI: 10.1177/000486588902200303.

Laster K (1994) Arbitrary chivalry: Women and capital punishment in Victoria, 1842–1967. In Philips D and Davies S (eds) A Nation of Rogues? Crime, Law and Punishment in Colonial Australia: 166–186. Carlton: Melbourne University Press.

Lyons M (2001) Introduction. In Lyons M and Arnold J (eds) A History of the Book in Australia 1891–1945: A National Culture in a Colonised Market: xiii–xix. St Lucia: University of Queensland Press.

Mazerolle P (2008) The poverty of a gender neutral criminology: Introduction to the special issue on current approaches to understanding female offending. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology 41(1): 1–8. DOI: 10.1375/acri.41.1.1.

McConville C (1980) The location of Melbourne’s prostitutes, 1870–1920. Australian Historical Studies 19(74): 86–97. DOI: 10.1080/10314618008595626.

McQuilton J (1987) Policing in rural Victoria: A regional example. In Finnane M (ed.) Policing in Australia: Historical Perspectives: 35-58. Kensington: NSW University Press

Meier WM (2011) Property Crime in London, 1850–Present. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mukherjee S, Walker JR and Jacobsen EN (1986) Crime and Punishment in the Colonies: A Statistical Profile. Kensington: History Project Inc.

Murphy K (2010) Rural womanhood and the ‘embellishment’ of rural life in urban Australia. In Davison G and Brodie M (eds) Struggle Country: The Rural Ideal in Twentieth Century Australia: 02.1–02.15. Clayton: Monash University ePress.

Nagy V (2015) Nineteenth-century Female Poisoners: Three English Women Who Used Arsenic to Kill. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Overington C (2014) Last Woman Hanged: The Terrible, True Story of Louisa Collins. Sydney: HarperCollins.

Parker KF & Reckdenwald A (2008) Women and crime in context: Examining the linkage between patriarchy and female offending across space. Feminist Criminology 3(1): 5-24. DOI: 10.1177/1557085107308456

Philips D (1994) Anatomy of a rape case, 1888: Sex, race, violence and criminal law in Victoria. In Philips D and Davies S (eds) A Nation of Rogues? Crime, Law and Punishment in Colonial Australia: 97–122. Carlton: Melbourne University Press.

Piper AJ (2015) ‘I’ll have no man’: Female families in Melbourne’s criminal subcultures, 1860–1920. Journal of Australian Studies 39(4): 444–460. DOI: 10.1080/14443058.2015.1082072.

Piper AJ (2018) ‘Us girls won’t put one another away’: Relations among Melbourne’s prostitute pickpockets, 1860–1920. Women’s History Review 27(2): 247–265. DOI: 10.1080/09612025.2017.1321613.

Piper AJ and Nagy V (2017) Versatile offending: Criminal careers of female prisoners in Australia, 1860–1920. Journal of Interdisciplinary History 48(2): 187–210. DOI: 10.1162/JINH_a_01125.

Piper AJ and Nagy V (2018) Risk factors and pathways to imprisonment among incarcerated women in Victoria, 1860–1920. Journal of Australian Studies 42(3): 268–284. DOI: 10.1080/14443058.2018.1489300.

Ross S and Skondreas N (2000) Female prisoners: Using imprisonment statistics to understand the place of women in the criminal justice system. Paper presented at Women in Corrections: Staff and Clients Conference, Adelaide, 31 October–1 November, 2000.

Rychner G (2017) Murderess or madwoman? Margaret Heffernan, infanticide and insanity in colonial Victoria. Lilith 23: 91–104. Available at https://search-informit-com-au.ezproxy-f.deakin.edu.au/documentSummary;dn=042066007136478;res=IELHSS (accessed 21 January 2019).

Schwartz J and Gertseva A (2010) Stability and change in female and male violence across rural and urban counties, 1981–2006. Rural Sociology 75(3): 388–425. DOI: 10.1111/j.1549-0831.2010.00016.x.

Steffensmeier D and Haynie D (2000) Gender, structural disadvantage, and urban crime: Do macrosocial variables also explain female offending rates? Criminology 38(2): 403–438. DOI: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2000.tb00895.x.

Swain S and Howe R (1995) Single Mothers and Their Children: Disposal, Punishment and Survival in Australia. Oakleigh: Cambridge University Press.

Thurgood N (1988) The Gold Escort Robbery Trials. Kenthurst: Kangaroo.

Tonnies F (1957) Community and Society. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press.

Twomey C (2002) Deserted and Destitute: Motherhood, Wife Desertion and Colonial Welfare. Kew: Australian Scholarly Press.

White S (1979) Howard Vincent and the development of probation in Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom. Historical Studies 18(73): 598–617. DOI: 10.1080/10314617908595616.

Wirth L (1938) Urbanism as a way of life. American Journal of Sociology 44(1): 1–24. Available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/2768119 (accessed 21 January 2019).

Wright C (2003) Beyond the Ladies Lounge: Australia’s Female Publicans. Carlton, Victoria: Melbourne University Press.

Zedner L (1991) Women, Crime, and Custody in Victorian England. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/IntJlCrimJustSocDem/2019/7.html