|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy |

Contagion of Violence: The Role of Narratives, Worldviews, Mechanisms of Transmission and Contagion Entrepreneurs

Miranda Forsyth

Australian National University, Australia

Philip Gibbs

Divine Word University, Papua New Guinea

|

Abstract

This paper develops the theory of the social contagion of violence by

proposing a four-part analytical framework that focuses on:

(1) contagious

narratives and the accompanying behavioural script about the use of violence as

a response to those narratives; (2)

population susceptibility to these

narratives, in particular the role of worldviews and the underlying emotional

landscape; (3) mechanisms

of transmission, including physical and online social

networks, public displays of violence and participation in violence; and (4)

the

role of contagion entrepreneurs. It argues that a similar four-part approach can

be used to identify and imagine possibilities

of counter-contagion. The

application of the theory is illustrated through examination of the recent

epidemic of violence against

individuals accused of practising sorcery in the

Enga province of Papua New Guinea, a place where such violence is a very new

phenomenon.

Keywords

Contagion; Melanesia; sorcery; violence; witchcraft.

|

Please cite this article as:

Forsyth M and Gibbs P (2019) Contagion of violence: The role of narratives, worldviews, mechanisms of transmission and contagion entrepreneurs. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 9(2): 37-59. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.v9i2.1217

![]() This

work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution

4.0 International Licence. As an open access journal, articles are free to

use with proper attribution. ISSN: 2202-8005

This

work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution

4.0 International Licence. As an open access journal, articles are free to

use with proper attribution. ISSN: 2202-8005

This article develops the theory of the social contagion of violence (Fagan, Wilkinson and Davies 2007) by examining the current epidemic of violence against individuals accused of practising sorcery in the Enga province of Papua New Guinea (PNG). Violence against those accused of using sorcery or witchcraft is both a contemporary and historical phenomenon worldwide. It often manifests in patterns of sudden outbreaks that then subside, only to flare up again later. However, in Enga, sorcery accusation-related violence (SARV) is a new phenomenon, with the first cases appearing around 2010. This makes Enga a particularly valuable case study into how novel forms of violence associated with newly perceived threats can spread across a society.[1] We propose a four-part analytical framework through which to analyse contagion of violence: (1) narratives of contagion, revealed in the case study as a story about sanguma (a particular form of sorcery) accompanied by a behavioural script about the appropriateness of violence as a response to those accused of being sanguma; (2) population susceptibility to these narratives, in particular the role of worldviews and the related emotional landscape; (3) mechanisms of transmission, including physical and online social networks, public displays of violence and participation in violence; and (4) the role of ‘contagion entrepreneurs’. It argues that a similar four-part approach can be used to identify and imagine possibilities of counter-contagion of violence.

This study’s insights into the centrality of stories or narratives in the contagion (and counter-contagion) of violence are also relevant for other types of ‘outbreaks’ of violence based on othering, such as race-based vigilantism, homophobic or anti-Semitic violence. More broadly, the findings also highlight the role of social networks, particularly peer-to-peer networks (Best et al. 2016: 114) and social media, and their role in both spreading and containing violence.

The phenomenon of SARV in Enga can be contextualised by the 2018 case of ‘Anna’, a divorced mother of five children, who was accused of being a sanguma (witch) and ‘eating’ the heart of a little girl who had suffered a seizure the previous day. Anna was accused because she had sold some avocados on behalf of another woman who had briefly held the little girl before she got sick. As a result of this, that other woman was accused and tortured, and subsequently died from her injuries. The next morning, approximately 10 men took Anna from her house and her baby, tied her up and tortured her with heated iron rods for seven hours. She recounts crying out, ‘Jesus, my body has had enough of this. Take my life, I want to die’. Luckily she escaped, but stated that no-one had sympathy for her; they all said, ‘She is a witch. Burn her or throw her into the Lai River’.

Our article begins by briefly outlining the general phenomenon of sorcery or witchcraft in PNG, including how it has been analysed in the largely anthropological literature. It then outlines SARV and the main theoretical accountings proposed to explain this phenomenon. Next, we present the theory of the social contagion of violence, the framing structure for our analysis. This is followed by the empirical study of SARV in Enga, detailing the nature of SARV in Enga today, in particular discussing its geographical and temporal spread. From here, we analyse the contagion of SARV through identifying the four components. Finally, we consider mechanisms of counter-contagion and the possibilities they open for social control and making the personal political.

This article is based on a multi-year interdisciplinary study of SARV across PNG, the intention of which is to document and analyse both the nature and scope of the problem, and the nature and impact of the responses by government and non-government organisations (NGOs) and individuals (see further Forsyth et al. 2019; Stopsorceryviolence.org 2019). The study is multi-scalar, focussing at the national level, and also in greater detail on particular provinces (primarily Enga, Bougainville and the National Capital District, and secondarily Morobe and Jiwaka). This article provides a specific account of SARV in the province of Enga, but occasionally refers to the wider national context.

The study developed an innovative, participatory, mixed-methods methodology to address the difficulties of accessing reliable data (see further Forsyth et al. 2017 and Losoncz, Forsyth and Putt 2019). Official records in PNG, such as court, police and hospital records, are fragmented or inconsistent (Lakhani and Willman 2014: 5, 10). They often do not record whether a crime or injury resulted from sorcery accusations and lack the vast amount of SARV cases that are never reported to state authorities.

Therefore, we rely on ethnographic literature, semi-structured interviews and the construction of two new datasets. The first dataset focuses on trends in SARV cases reported by national newspapers and courts over at least a 20-year period. The second, the cornerstone of the project, is the collection of information on incidents of accusations of sorcery that result in violence and those that do not result in violence in the provinces identified above (starting with the primary ones in 2016 and expanding to the secondary ones in 2018). Incident forms are completed by a network of data collectors recruited from the local community to reduce the understandable distrust of outsider researchers. Gaining access to sensitive information is one challenge; the other is obtaining as much information about the incident as possible and recording it consistently. Instead of recording a single person’s experience or recollection of an incident, recorders are instructed to talk to a range of witnesses to collect as much information as possible about the incident, victims and accusers before completing the incident form. The dataset is designed so that data can be analysed either at an incident or a victim level, as many incidents have more than one victim.

Limitations affect these collection methods. Most fundamentally, the challenging geography and lack of security caused by sporadic tribal fighting makes it difficult for local recorders to travel freely and follow-up all reports of cases. There is likely an under-counting of cases of sorcery accusations that do not lead to violence, but less chance of under-counting cases of sorcery accusations that do lead to serious physical violence, due to the triangulation methods employed (in particular, checking all accounts with local NGOs and human rights activists involved in rescues and repatriation of victims, along with newspaper and social media reports). It is highly unlikely there are any cases recorded that did not actually occur, although some details recorded in incident data may not be totally correct.

Data collection methods were approved after a rigorous ethics approval process, which required: anonymity of data, non-involvement of any children as interviewees, and a restriction on interviewing perpetrators of SARV. Our ethical obligations prioritised the safety of those being interviewed and consulted, and of those conducting the research.

Our article draws upon over 50 semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders in Enga (principally police, survivors, community leaders, village court magistrates, health officials and local activists), our newspaper reports and judgments database, and our incident database for Enga. All quantitative data discussed are drawn from the incident database dated January 2016–December 2018.

The particulars of sorcery and witchcraft vary significantly around the world and throughout PNG, and change dramatically over time, accommodating themselves to new situations with great agility. Witches are now said to ride in helicopters, communicate through mobile telephones and even to meet together in a parliament. Rather than a fixed set of beliefs, it is more useful to conceptualise sorcery and witchcraft as phenomena that encompass discourses, practices and particular modes of reasoning, all existing within a particular magical worldview.[2] A common dimension of sorcery is a living individual’s power and knowledge to cause some kind of effect in the physical world through supernatural forces.

Throughout Melanesia, sorcery and witchcraft provide an explanatory framework that makes sense of events in the world, and especially of illness, death and misfortune. As such, identifying a person as responsible for sorcery is a way of attempting to reclaim control over situations that appear out of control. In 2012, the PNG Constitutional Law Reform Commission reported on its extensive consultation and research into sorcery beliefs in PNG. It found the majority of Papua New Guineans strongly assert that sorcery is real, regardless of their level of education, gender, religiosity, or whether they reside in urban (including overseas) or rural areas. One effect of believing in witchcraft is an assumption that others desire to do you harm. Geschiere coined the phrase ‘the dark side of kinship’ to explain how people’s suspicions often fall upon those they are close to, leading to ‘the frightening realization that there is jealousy and therefore aggression within the family, where there should only be trust and solidarity’ (1997: 11). Ashforth (2002: 69) used the notion of ‘spiritual insecurity’ to explain the impact produced by belief in witchcraft: ‘life in a world of witches must be lived in the light of a presumption of malice: one must assume that anyone with the motive to harm has access to the means and that people will cause harm because they can’. While both anthropologists worked in Africa, their observations are highly applicable to Melanesia.

Many anthropologists frame sorcery or witchcraft itself as a mechanism of social control that discourages socially unacceptable behaviour (Bowden 1987: 193) and acts as a levelling force to enforce social equality (Black 2011: 62–63). Some have also followed Marwick’s (1970) observation that rapid social changes are likely to cause an increased preoccupation with beliefs in sorcery and witchcraft, and that levels of sorcery and witchcraft beliefs can be read as a ‘social strain-gauge’. Scholars have also identified superstition and superstitious behaviour as almost universally emerging in response to uncertainty—‘to circumstances that are inherently random and uncontrollable’ (Vyse 1997: 201).

More contemporary literature on witchcraft and sorcery has sought to demonstrate how ‘occult cosmologies’ flourish in the interstitial spaces of modernity, showing how they thrive when people encounter the insoluble contradictions and unfulfilled desires modernity presents (Comaroff and Comaroff 1993, 1999, West 2001). These analyses view discourses of sorcery and witchcraft as a ‘viable vocabulary’ for commenting on the changing equalities associated with modernity, such as those related to the rise of cash and market economies. As Geschiere (2016: 226) noted, this vein of scholarship demonstrates a ‘general tendency to try and reduce witchcraft imaginaries to something else (to what would be “really” behind all these mesmerizing fantasies)’. We argue that a more emic perspective is essential when seeking to understand the violence provoked by sorcery phenomena, in order to explain the fear and sense of injustice it causes. This necessitates taking seriously the narratives of sorcery and witchcraft within the context of the worldview of the relevant population.

Sorcery Accusations and Related Violence in PNG and Beyond

Fear and suspicion that a death, illness or misfortune has been caused by a particular individual’s use of magic can, in certain contexts, lead to accusations, stigmatisation, violence and even death. It is increasingly globally recognised that SARV (sometimes referred to as ‘witch-hunting’) is a form of extreme human rights violation occurring in many countries (Forsyth 2016, WHRIN 2017). In 2009, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions observed there is ‘little systematic information on the available numbers of persons so accused, persecuted or killed, nor is there any detailed analysis of the dynamics and patterns of such killings, or of how the killings can be prevented’ (2009: 13). Hutton (2004: 430) summarised the current state of knowledge:

It is a general rule that dramatic economic, social and cultural changes commonly induce a sharp increase in witch-hunts among people who have a traditional fear of witches. It is also a rule, however, that such an increase is not an automatic result of such changes.

Like sorcery beliefs themselves, the classic anthropological approach pioneered by Evans-Pritchard (1937) views witch-hunting as functional (i.e., performing social functions such as boundary-making to strengthen community identity during times of uncertainty). Yet, such an explanation is unsatisfactory in at least two respects in regard to PNG, and perhaps more broadly. First, it does not accord with the empirical evidence that in many instances SARV does not strengthen ‘in-group’ bonds, but rather weakens them through generating fear and suspicion. One interviewee stated, ‘We don’t have peace and unity because of violence [SARV]. The spirit of death is also affecting those who tortured them. The life and relationship in the community is disturbed because of violence’. Thus, we suggest that SARV is not just a response to social strain and confusion of group identity (Erikson 1966); it is also a cause of breaking social bonds and community trust. This occurs through destructive feedback loops of suspicion, violence and payback. As Siegel (2006: 2) observed, ‘it is a violence that inheres in the social and that turns against it’. This element is overlooked by the functionalist focus on group solidarity (see Hutton 2017: 35). Second, the static nature of the functional approach does not account for individual and institutional agency in addressing SARV; this agency results in significant local variations in the level and extent of both accusations and violence.

Attempts have also been made to explain the rises and falls of SARV using economic models. For instance, Fisman and Miguel (2008; Miguel 2005) sought to demonstrate causal connections between income shocks and the murder of elderly women as witches in Africa as a rationalist community-based decision to sacrifice the least useful member of the community during crises. However, economic models prove unsatisfactory in light of the current project’s data. In particular, economic explanations do not resonate with the emotionally-charged landscape surrounding SARV in PNG, one characterised by fear, shame and a strong sense of injustice. It is also inconsistent with our empirical data that sometimes it is highly educated, successful or wealthy individuals accused of sorcery (Forsyth et al 2019).

Various other incomplete hypotheses have been proposed to explain the variations in time and place of SARV in PNG. For example, Meggitt (1981) linked escalation of accusations to increased mobility and upsurge in malarial sickness and death (meaning more ‘unnatural deaths’ needing explanation); Haley (2001) to drought and deaths (again leading to increased mortality needing explanation); Strathern and Stewart (2012) to decline in tribal fighting (and so seeking supernatural over physical means of attack); and Gibbs (2012) to deterioration in law and order (removing social brakes on violence, permitting engagement with impunity). However, such singular analyses do not sufficiently explain why, for example, in Enga in 2017, there were areas with the above characteristics that experienced no sorcery accusations, some where there were many accusations but no violence, and others where there were few accusations but many deaths.

Social Contagion of Violence

This article both draws upon and advances the theory of social contagion of violence in explaining the spatial and temporal clustering phenomenon of SARV. Contagion effects have been documented in regard to a wide variety of phenomena including obesity, happiness, ideas (Fowler and Christakis 2010), gun violence and suicide (Green, Horel and Papachristos 2017; Towers et al. 2015), piracy, civil unrest, hijackings, assassinations and kidnappings (Bandura 1973; Berkowitz 1973; Landes 1978). Those studying the contagion of violence seek to understand: (1) What mechanisms or processes drive contagion of violence? (2) What makes a population resilient or susceptible to new forms or increased incidents of violence? and (3) How can a contagion of violence be contained? (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council [IMNRC], 2013).

Scholars concerned with contagion of violence in particular have demonstrated how clusters of violent incidents can sometimes occur due to interconnections between incidents, rather than solely due to external or independent risk factors (see IMNRC 2013). Violence can be viewed as potentially contagious at many different scales—between countries, regions, provinces and neighbourhoods/villages (see Buhaug and Skrede Gleditsch 2008). Contagion of violence can manifest geographically (spreading from one place to another) or temporally (elevated levels for periods of time); one type of violence can also spread to other types of violence (such as high levels of murder influencing high levels of sexual violence) (IMNRC 2013).

Varying interconnections or vectors can promote contagion, each with differing levels of salience dependent on context. Common vectors include geographic proximity, media reporting, exposure to violence through either direct participation or witnessing, shared membership of organisations, migration ties (Di Salvatore 2018) and, more broadly, social contagion. Social contagion is ‘the mutual influence of individuals within social networks who turn to each other for cues and behavioural tools that reflect the contingencies of specific situations’ (Fagan et al. 2007: 689; Green et al. 2017: 327). Fowler and Christakis (2010: 5337) demonstrated through experimental investigations and observational studies that the spread of behaviours may arise from the spread of social norms through social networks, and that each person in a network can influence dozens or even hundreds of people, some of whom he or she does not even know.

In addition, contagion can occur through diffusion of facilitative objects such as guns, suicide vests, certain drugs and cyberbullying (Braithwaite and D’Costa 2018). Third parties can play an important role in spreading violence between networks, either animating or intensifying violence once conflict begins, or helping to mediate and suppress it. Third parties also convey the outcomes of violent events beyond social networks initially involved in the violence (Fagan et al. 2007: 710).

In terms of understanding exactly how contagion occurs, the theory of behavioural ‘scripts’ or sets of normative expectations is particularly useful. Scripts serve as ‘programs’ of behaviour that ‘provide instruction on how to react to certain stimuli, primed by previous exposure, observation and response’ (IMNRC 2013: 20). Huesmann and Kirwil (2007: 547) argued that ‘social behaviour is controlled to a great extent by social scripts’. Transmissible from one person or group to another, these scripts instruct how to proceed in a given scenario. As we elaborate shortly, this theory has considerable explanatory force in understanding the virulent pathway of SARV through Enga this decade.

Contagion of violence should not be assumed from spatial or geographic clusters of violence, as a variety of external factors may contribute to temporal patterning (Carcach, Mouzos and Grabosky 2002: 183, 190). Instead, it is necessary to determine whether contagion is present. This has usually been assessed through statistical analysis of detailed crime datasets, such as historical homicide data (Carcach et al. 2002), maritime piracy datasets (Di Salvatore 2018), or detailed social network analysis of police records (Green et al. 2017). However, the data sources necessary to conduct such analysis are unlikely to be present for crimes such as SARV, for which official records are not maintained, and violence is partially hidden, requiring development of new methods.

If patterns of violence can be attributed to contagion, this does not render external factors irrelevant. Indeed, there is often an interdependence between contagion and external factors. External or structural factors can increase or reduce a community’s resilience or susceptibility to the incoming transmission of violence (Fagan et al. 2007: 691). For a violence script to infect, certain individual, social and environmental factors must be present (IMNRC 2013: 28). For instance, poverty tends to make communities more susceptible to contagions of violence (IMNRC 2013). The data presented below demonstrate how the novelty of the violence, together with the novelty of the underlying threat it is framed as responding to, can operate as significant factors in its spread. Further, it shows how communities may, to some extent, inoculate themselves against contagion of particular forms of violence, such as through learning over time about the harm and suffering caused to members of the community.

If contagion is determined to be an explanatory factor for the patterning of violence in a particular context, this finding has a range of theoretical, methodological and normative implications. Sources of risk will be identified differently (endogenous and exogenous) and temporal understandings of the epidemic will change. This opens new avenues of intervention to prevent contagion in vulnerable communities and counter the contagion in those already affected.

Background and Nature of SARV in Enga Today

Located in the Highlands of PNG, Enga is a province of roughly 500,000 people. Approximately 85% of the populace speak dialects of the Enga language, an unusually homogeneous language block for PNG; the remainder are ethnic minorities living predominantly in Enga’s western edges and in remote and isolated locations. Traditionally, the population was dispersed through garden lands linked through loose clusters of clans, with the most significant sociopolitical unit being on average about 350 people (Lacey 1978).[3] This structure was not significantly changed by colonisation, or when Enga became a province in 1975 upon PNG’s independence; Engan society today is still strongly structured through clans and tribal groupings. This has a major impact on SARV and its policing—one person’s problem becomes everyone’s problem. When one person dies, it is a great loss for the tribe. When one person is arrested, every tribe member feels threatened.

Enga faces a range of challenges including inequality and poverty, declining health and education systems, polygamy, weak law and order, normalisation of violence and gender inequality (Gibbs 2016: 333–337). In an article tellingly titled after an Enga proverb about gender roles—‘You have a baby and I will climb a tree’—Gibbs (2005: 15) noted ‘[g]ender differences still structure relationships between men and women in Enga society’. Gibbs (2016: 336) further observed that today ‘[f]ear of contamination by women has been replaced by issues of power and control’. From the late 1980s, vast cash flows from the large goldmine in the province generated social change, increasing inequality within the province (Gibbs 2016: 334). Extensive law and order problems persist, including regular tribal fighting, often shutting down government systems for weeks (Peake and Dinnen 2014). The 2014 crime report in PNG identified Enga as a crime ‘hotspot’ (Lakhani and Willman 2014: 8, 11), and due to high rates of tribal fighting, the 2018 survey could not even include it.

The anthropological record is clear that Enga traditionally lacked sorcery or witchcraft beliefs and practices that led to accusations and violence (Pupu and Wiessner 2018: 11), except on its remote fringes or in very occasional cases.[4] This stands in contrast to nearby provinces such as Simbu, where SARV has been well recorded for many years by missionaries and researchers (Zocca 2009). Recently though, a prevalent form of sorcery belief in neighbouring provinces known as sanguma has entered Enga. Sanguma is strongly associated with the idea of people (known also as sanguma) who appear normal but are possessed by a sanguma spirit, stealing other peoples’ hearts to feast on, often as part of a group led by a ‘boss’ sanguma.

Central Enga’s encounter with SARV commenced around 2010.[5] In this year, the second reported national court decision involving SARV murder in Enga occurred (after a 30-year hiatus), and national newspapers first started reporting SARV cases in Enga. Neither of these indicators is reliable alone, as there is significant under-reporting of cases in newspapers, widespread impunity for SARV perpetrators, and multiple failures of the criminal justice system to trial such cases. However, this period also accords with the recollections and impressions of all key stakeholders in Enga, and the anthropological and historical literature. In our incident database related to Enga, in 79% of cases in which the answer was recorded (81/103), respondents said there was no customary way to manage accusations of sorcery. Where an explanation was given for why no customary ways existed, in 85% of cases (57/67 open-ended comments) the response involved some version of the explanation that sorcery is a ‘foreign’ concept or a ‘new thing’ or a ‘first-time experience’. This idea, that sanguma is new and introduced, also features strongly in our semi-structured interviews, in which ‘careless women’ are identified as responsible for its introduction (associating their actions with Eve’s role in awakening evil). The popular narrative is that Engan women visited nearby Simbu province to buy special love magic to stop their husbands taking new wives (polygamy is common in Enga) but were sold the wrong magic—sanguma magic.

Since 2010, the incidences of SARV have been significant, although there is no reliable official data on which to base claims about extent or trends. Between 1996 and 2010, no cases of SARV were reported in Enga in national newspapers and courts, while between 2010 and 2018, 19 were reported. Anton Lutz, a Lutheran missionary and active advocate against SARV in Enga, reported that when his father worked as a hospital doctor there from 1986–2010, he never dealt with injuries resulting from sanguma accusations and that SARV was a ‘new trend’ (ABC Pacific Beat 2017). The extent of concern about the rapidly rising number of cases, especially cases resulting in torture and/or death, can be observed in public statements made by police and provincial leaders. For instance, in 2015, the police established a specially designated sorcery desk in the provincial capital of Wabag. In 2016, Provincial Police Commander George Kakas stated that SARV was ‘prevalent’ in the province (The National, 2016). In 2017, the acting police commander said sanguma-related killings were reaching frightening proportions (The National, 2017), and emphasised an urgent need to combat ‘the evil spreading like wildfire across the province’ (The National, 2017). The provincial governor in November 2017 stated: ‘This week alone there have been two more incidents of sanguma accusations in Enga province and more than 20 innocent women in the space of this past month have been victims of this accusation based violence’.[6]

From 2016, the SARV project database provides greater clarity about the extent and nature of both sorcery accusations and SARV. Spanning 1 January 2016–December 2018, our database records 43 incidents of sorcery accusation that lead to major physical violence and 82 that did not lead to violence, involving in total 201 accused. The high number of accused is because in 41% of cases, more than one person was accused, most often due to the first accused being forced to name others during torture or intimidation.[7]

The SARV database provides important insights into the main characteristics of these incidents. First, through analysing the recorded characteristics of those who have been accused and faced violence in Enga from the incident forms, we find that they are:

• overwhelmingly women (90%)

• often accused of sorcery before (49%)

• as likely to have been born in the community (46%) than from another community (54%)

• economically of the same status as others in the community (74%)

• mainly completely uneducated (59% had never started school)

• mostly not in paid employment (93%).

However, in some cases, the accused were well educated and employed (including teachers). In terms of the age of victims, our data show 46% are 19–40 years and 43% 41–60 years. However, given that the population numbers of women in this older age category is only slightly over a half of the number in the younger category, it makes the older group significantly more susceptible. There were also victims who were both very old and very young; a number of cases during this period involved the accusation and torture of children as young as six (often children of accused women).

Each incident may also involve secondary victims, such as children of those accused who may face loss of parents, homes and property, and social stigmatisation. Of those incidents that led to violence 36% involved killing, leading to 26 deaths. A further 30 accused were left with a permanent physical injury. In 26 cases (involving 55 accused individuals), the accused persons were tortured, with the ostensible reason in 87% of cases to obtain a ‘confession’. The violence occurred both in public and in private in 49% of cases, followed by 28% public-only, and 23% private-only and over various timespans, ranging from a few hours (28%) to several days (17%). In most cases (53%), it spanned a day. In 83% of cases there was a known incident that started the accusation. As many as 81% of these known incidents were either death or sickness.

The database also shows particular characteristics of SARV perpetrators. In our recorded cases in Enga, 14% were committed by between 1–4 people; 29% were committed by 5–20 perpetrators; 14% by 21–50, and by far the largest proportion of cases—43%—were committed by more than 50 people. We had expected to find that the violence was overwhelmingly perpetrated by men but the data show a mixture of genders and ages in 57% of cases and only ‘mostly young men’ in 41% of cases. Similarly, although public narratives of the mob being fuelled by drugs or alcohol are common, in none of the cases were all of the perpetrators affected by drugs and alcohol. According to our data, some perpetrators were affected in 88% of the cases, and none were affected in 12% of the cases.

In terms of the relationship between accused and accuser, it is much more common for there to be a reported blood/family or same-tribe relationship between the accused and the main accusers than no particular relationship (only 10% recorded no particular relationship). A pre-existing underlying conflict between accuser and accused was known in 61% of cases, most commonly jealousy over money and goods, followed by polygamy and sexual jealousy and land disputes. However, it is not possible to automatically interpret the latter as suggesting that the accusation is merely a pretext for an ulterior motive (although we acknowledge accusations may be used strategically), because people are more likely to be suspicious of those they know already have a grudge against them.

The Geographic and Temporal Spread of SARV in Enga

The temporal patterning of SARV cases across 2016 and 2018 is shown in the timeline in Figure 1. This timeline is based on multiple (triangulated) data sources including our incident database, newspaper and judgment database, other media reports and interviews with the main individuals involved in rescuing or attempting to rescue the accused. The timeline shows a significant increase in cases starting from early 2017.

Figure 1: Timeline showing number of SARV cases 2016–2018.

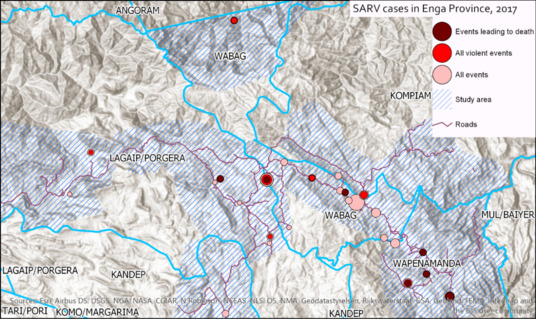

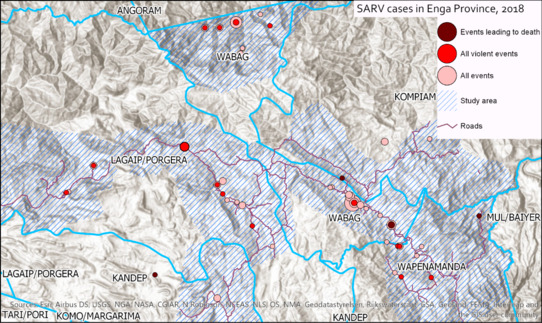

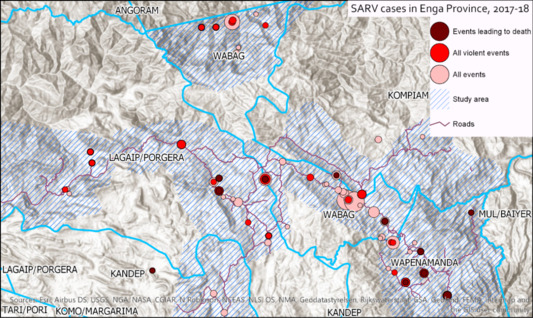

The geographical clustering of incidents is shown in Figures 2–4. Figure 2 shows SARV incidents in 2017, Figure 3 shows SARV incidents in 2018 and Figure 4 shows both years plotted together. The purple line represents the road network, with data clusters making it apparent the vast majority of cases occur near a road. Since the roads follow valleys and people tend to live in valleys, roads are generally associated with higher population density and ‘density’ of cases therefore follows. The shaded areas show the geographical area in which our local recorders gathered data and the blue lines show the different districts. The different coloured dots refer to the different types of SARV; the larger the dot, the larger the amount of SARV reported for that location. It is evident from the map that SARV in all its forms (violence and non-violence) has spread significantly over the two-year period, often radiating outwards from earlier sites.

Figure 2: SARV cases in Enga Province, 2017.

Figure 3: SARV cases in Enga Province, 2018.

Figure 4: SARV cases in Enga Province, 2017–2018.

Contagion of SARV in Enga

SARV has become a serious problem in Enga in a short period, going from barely any cases or cultural traditions related to sanguma to a virulent outbreak. No significant changes in structural or other external factors can account for the patterning of accusations and violence. Therefore, the theory of social contagion of violence is useful for analysing and accounting for these developments and patterning of violence, as it also highlights endogenous factors. Mindful of Christakis and Fowler’s (2011: 563) insight that different things spread in different ways and to different extents, we set out a four-part framework to analyse this contagion—(1) contagious narratives (what is being transmitted?); (2) community susceptibility; (3) mechanisms of contagion; and (4) entrepreneurs of contagion.

Contagious Narratives

SARV is transmitted in Enga through a particular narrative or story about sanguma and an accompanying behavioural script about how to respond to that narrative. Enga’s sanguma narratives feature women (and occasionally men) becoming infected or possessed by a sanguma spirit through various means; those infected are impelled to seek out and ‘eat’ the hearts of living people, often in company with other sanguma. Women are identified as sanguma based on allegations of being in places they normally should not be (such as graveyards), manifesting strange behaviours (such as not crying at funerals) or showing excessive desires (e.g., greed in consuming meat).

Our study shows a strong uniformity in the responses about what the victims of SARV were accused of doing. In 52% of recorded cases (60/115 open-ended comments), the victim was accused of having ‘taken’ or ‘eaten’ the heart of another person, often a child. Sometimes they are said to have hidden it or shared it with other sanguma. This striking consistency, especially given the recentness of this narrative in Enga, offers valuable insights into the importance of narrative in spreading violence. In particular, it reinforces the idea within the community that it is the accused who are at fault and to be feared, justifying the use of violence against them.

In interviews as well, the narrative of taking the heart is prevalent. A nurse stated:

If a sanguma accused come on my way, I do feel the fear. It’s a psychological thing. I do fear but I have to treat them, dress their wounds, give them medicine, etc. At the back of my mind, I believe she is a sanguma, so she might take my heart.

Another nurse reported:

I witnessed one post-mortem. The relatives of the deceased claimed that the accused has taken the heart of the dead body. The entire community claimed that the accused had taken the heart, so they brought the body to the hospital to confirm whether the heart is there or not. But doctors found out that the heart is still there.

Highly dynamic, the sanguma narrative adapts easily to new situations through extension of the underlying cultural logic. For example, we documented a case of people travelling on a public bus where the engine stopped as the bus climbed a hill. After exiting the bus, the passengers walked uphill and noticed one woman still sitting inside the bus. Since she was new to the place, she had decided to wait inside. The other passengers started investigating her and one of the passengers claimed she was a sanguma; other passengers agreed, saying ‘this woman takes the heart of the vehicle and ate’.

The importance of stories as a device of contagion is reflected by one of our recorders:

I tell a story and someone will add to it and gradually it grows. I will hear stories about it [sanguma spirit] coming from Simbu like a frog that jumps inside and this is what is eating people. Then it becomes like a bushfire. They tell untrue stories about women crossing water and the like. I asked why they have to cross water and they say the water will pull down the power of Satan, and if the woman refuses, then it is a sign that she must be a sanguma. I asked them where it comes from and they say Porgera [in Enga] or Tari [in a different province], or even USA.

Reflecting on his experiences in Enga, a long-term expatriate Baptist pastor similarly commented that the stories are ‘so credible’, and that, ‘some of the stuff they are seeing and reporting is very real and very powerful. Maybe there is a side to the spiritual world going on here that I am not privy to and you have to be open to that’.

The sanguma narrative is transmitted with a behavioural script that provides the ‘appropriate’ response to a woman believed to be a sanguma. This script requires torture, often involving burning, to obtain a ‘confession’, or to force naming of other sanguma, or to asking the accused to replace the heart and bring the sick/dying person back to health/life again. Again, there is a high degree of uniformity in violence in the cases recorded in our database: 62% of violent cases involve torture to obtain a confession; and in 52% of violence cases, the victim is burnt. A nurse observed: ‘Most of the accused victims are burnt. They only seek medical support when they are burnt or tortured’.

Both narrative and script play the important role of justifying the violent actions, setting the moral compass of what is often a group response. A police officer noted:

When police arrive at the torture or killing sites and demand the perpetrators to surrender, the community cover up by saying, ‘We all agreed and tortured her because she is a sanguma. We accused her because she had taken the heart and the person is dying’.

In many instances, the accused women themselves perform according to the script, either confessing or blaming others, or claiming they have given the heart to another sanguma. One interviewee stated:

People say that the sorcerer has taken the heart and hide it somewhere safe. Often times they claim that, they place the heart on the branches of the trees. The accused said that just to avoid pain. They will say that, they put it here and there. But in fact they are just lying to avoid pain.

The women’s responses occur both in the context of torture and in anticipation of torture, thereby further embedding the script. For instance, one interviewee stated that before he witnessed such an event, he had not believed that women really were sanguma, but hearing a confession convinced him it was true. Sometimes, sick people coincidentally recover after a person has been tortured, further entrenching the legitimacy of the violence script, as people attribute recovery to the effectiveness of torture in persuading the accused to ‘put back’ the heart.

The above discussion is not meant to suggest that individuals and communities always adopt the sanguma narrative and accompanying violence behavioural script. In many communities, it is the subject of active contestation and reflection, as demonstrated in this conversation overheard by a Lutheran missionary with whom the research team works closely:

‘Instead of torturing them, we should just kill them ... throw the bodies in the river or something.’

‘But then the blood will spill on the ground and infect all of us with evil and witchcraft.’

‘Oh yeah.’

‘What if we gathered all their belongings and burned them, together with the women, blood and all?’

‘Could work. Or we could ask the police to arrest them?’

The next section describes how the spread and impact of the contagious narratives have to be contextualised within the susceptibility of particular populations, and by determining the mechanisms of transmission and the role of contagion entrepreneurs.

Population Susceptibility to Contagious Narratives

To understand why the sanguma narrative and violence script gained emotional and cognitive purchase in Enga, the particular characteristics of the population that make it susceptible require illumination. One highly relevant factor is the salience of a magical worldview or cultural logic within Enga. A magical worldview encompasses an understanding that an individual can affect the physical world through supernatural powers that contradict the laws of science. To enable transmission of the sanguma narrative and behavioural script to affect individual and group behaviour, the causal reasoning that underlies this magical worldview must be dominant. We know from recent research in the field of psychology that ‘magical thinking’ is present in every population to varying degrees, and that it can coexist with other modes of causal reasoning, even alongside scientific causal reasoning (Rosengren and Hickling 2000; Markle 2010). Recent studies have shown that in times of high uncertainty and risk, magical causal reasoning will be sufficiently attractive to motivate particular behavioural responses (Subbotsky 2018; Nguyen and Rosengren 2004).

The Engans did and do have a range of spiritual beliefs and a magical worldview in which the supernatural world has the capacity to affect the physical world through human agency. For example, there is a belief about yama, harm resulting from jealousy over food sharing. This was believed to be transmissible by everyone, but no punishment resulted because it occurred unintentionally, with no clear evidence proving personal responsibility. Engans also believe in magical spells, healing, sky-people and ancestral ghosts. Human illness or death was traditionally sometimes interpreted as due to ‘malicious’ ghosts (Meggitt 1981), but rarely were ghost attacks blamed on human agency. Instead, magic and ritual were used to protect and enhance, and to damage enemies’ crops and pigs. The Engan worldview had primed the population for the sanguma narrative to appear credible, and incited sufficient fear to justify widespread acceptance of the violent behavioural script when it finally reached Enga.

Receptiveness to the sanguma narrative has been enhanced by widespread uptake of Christianity in Enga since the 1940s, with its proliferation of evangelical and Pentecostal churches. Many churches preach about Satan, devils and possession in ways that resonate with and reinforce the sanguma narrative. One interviewee stated: ‘There are Christians claiming they can cast off the sanguma spirit in the person’.

The sanguma narrative also adapted to the cultural context of Enga, strengthening its appeal and credibility. For instance, its strongly gendered nature resonates with the sometimes virulent misogyny in Enga—as discussed, early anthropological accounts note Engan men’s fear of sexuality and female pollution, and frequent conflict between men and women. Normalisation of violence within Enga, largely manifested publicly in tribal fighting, is another important factor in explaining acceptance of the violent behavioural script. One community leader observed that ‘in our culture, violence is seen as a means to resolve conflict ... That is why when the community wanted to reject this sanguma spirit, they use their means, and that is violence’.

The final salient factor in the population’s susceptibility is the newness of sanguma in Enga. One of our recorders observed that it is like giving an apple to a person who has never seen one, and not knowing what to do with the foreign object, is easily persuaded to follow instructions on its use. Similarly, he said the need to torture is a story absorbed from other people as a ‘foreign belief’. Confusion caused by the sanguma narrative is illustrated by one case in which a community grew suspicious a sanguma was at work but did not know how to identify the individual responsible. Seeking help from a neighbouring village, they were told to make all women walk through the river and watch who had frogs leap out of their mouths. Unable to see any frogs jump out, the villagers made the women hold a Coca-Cola bottle in their mouths, hoping to catch frogs. This combination of confusion, creativity and fear indicates a lack of guidance about how to proceed, as a result of which a proposed violent response can seem the ‘right’ solution. Uncertainty about how to proceed not only empowers those advocating violence, it also disempowers those advocating against it, as they lack a secure contra-narrative. A village court magistrate, one of the community leaders, confessed: ‘Personally I am not sure, whether they are actually eating the heart or falsely accusing somebody for nothing. I myself I don’t know. I am confused’. Afraid to break ranks when not absolutely certain that the non-violence message is right, people worry about endangering their community by advocating on behalf of the sanguma. Additionally, when one element of the contagious narrative contends there is an ‘evil network’ of sanguma sympathisers, speaking out on another’s behalf appears downright dangerous.

Our hypothesis is that if a society lacks a cultural tradition of managing unfamiliar types of sorcery beliefs and practices, the chances and intensity of the outbreak of violence increase for two reasons. First, the narrative is more likely to cause heightened emotions, such as fear. Second, the lack of cultural traditions to manage the sorcery narrative reduces the likelihood of processes being in place to stem the pressure for violent responses. Cultural traditions that may help, if present, include customary responses that require deliberation over time, which could curtail development of group hysteria, rituals for ‘cleansing’ those accused of sorcery in non-violent ways, or traditions of counter-magic that confine such warfare to the supernatural realm.

A case study of one area in Enga, Yampu, supports this hypothesis, as it has gradually developed resistance to SARV through learning from its ongoing experiences. Yampu was the site of three SARV incidents, in 2011, 2013 and 2016. In 2011, the woman accused of sorcery was tortured and locked in a house, which was burnt down. Our interviewee stated: ‘Advisers from the [other] provinces explained how someone became a witch and told them what to do’. This action had widespread support within the village and little pushback. In 2013, in a nearby village, two women were accused of taking the heart from a dead young man. Both women were tortured, then released, but one died. Senior police were involved in the torture, and the pastors claimed the women were possessed and no-one came to their rescue. The dead woman’s husband, who was from another village, took the whole village to the Wabag OMS (local/hybrid court) for killing his wife. Finding no evidence of sorcery, the OMS ordered compensation, which was paid the following year. In 2016, a woman was accused of killing her husband. She was tortured privately at night rather than publicly and despite receiving injuries was able to flee. She sought and received help from police and the church. Our interviewee observed that this time, there was no consensus about the appropriateness of violence: ‘People—men, community leaders—were saying sanguma was not real, that we have killed two and tortured three of our women, and there should be no more accusations’. This case illustrates how a community can start to build its immunity and resist the scripts of SARV through its lived experiences. It is particularly relevant that the interviewee noted how the community refers to those accused and tortured as being ‘our women’, thus, consciously including them again in the ‘in-group’ rather than the non-human group of sanguma.

Mechanisms of Transmission

The narratives of contagion are transmitted throughout Enga (and more broadly) through (1) networks that use both physical and online communication, (2) public displays of violence and (3) participation in violence. In terms of physical networks, it is relevant that these cases often occur in places linked through the road network on which increasing numbers of private and public vehicles travel, facilitating travel between communities (both inside and outside Enga), bringing stories of sanguma and the responses to it around the province. As SARV cases are terrifying and often involve public violence, they are perfect fodder for ‘tok win’ (gossip), so word spreads quickly.

Further evidence points to a significant role played by online networks in the spread of SARV. First introduced to PNG in 2007, mobile telephones experienced less than 5% saturation nationally that year (Suwamaru 2014; Watson and Duffield 2016.). By 2015, this saturation reached roughly 40%, with internet access growing steeply due to third- and fourth-generation telephones.[8] Increasing penetration of mobile telephones is highly contiguous with the SARV epidemic in Enga. Incidents of SARV are frequently filmed on mobile telephones (sometimes surreptitiously, sometimes publicly) and shared via social media. A range of motivations lead people to upload these images and footage, including: seeking to publicly criticise the perpetrators for their bad behaviour and inhuman treatment; condemning through telling others the tribe or clan has sanguma; warning women with sanguma to stop practising it or they will suffer similarly; or publicly boasting of having engaged in torturing and killing.

Mobile telephones also facilitate the work of the glasman. A type of diviner, the glasman plays a variety of roles in communities, including identifying the source of sorcery through such means as looking in a ‘glass’, visions and using ritual implements. We documented cases in which glasman identify sanguma by telephone, with fatal consequences for the woman identified. By contrast, mobile telephones are also used to call for help, rescue and to facilitate repatriation—transposing them into devices of counter-contagion.

The public spectacle of violence in SARV cases is another important mechanism that transmits both the sanguma narrative and behavioural script. The violence often continues over multiple days and is witnessed by the entire community, including children, providing opportunities for social learning through observation (Huesmann and Kirwil 2007). Thus, public spectacles play a role of intercommunity as well as intergenerational transmission. We hypothesise that the physical enactment of an ideal of justice is particularly influential in transmitting concepts of justice in a culture with oral legal traditions such as Enga. Each violent event provides a ‘lesson’ for participants, first-hand observers and those influenced by stories about the event communicated through gossip, social media, telephones, radio and newspaper reports.[9] These observations support the work of Lee-Ann Fujii (forthcoming) who argues that ‘public displays’ of violence allow for widespread participation in violence in ways that become infused with meaning and evoke alternative social orders.

Finally, participation in violence is itself a significant mechanism of transmission. SARV cases are overwhelmingly carried out by large mobs of people, as illustrated by a recent national court decision convicting 97 people of murder in one SARV incident in Madang province (State v John Kakiwi [2018] PGNC 273). Our SARV dataset shows this applies to Enga too, where most cases have 50 plus perpetrators. Large numbers of people participating in violent incidents increase the chances of repeat involvement, as participation normalises the use of violence. The embodied involvement of everyone present in the performance of violence creates experiential responses that have high salience in explaining future reactions to similar situations, as borne out by the geographical clustering of SARV discussed above.

Contagion Entrepreneurs

There are two main types of ‘contagion entrepreneurs’ in relation to SARV in Enga. The first are those perpetrators of violence who participate in multiple incidents of SARV, transmitting the narratives and role-modelling responses. In our interviews, we were told of perpetrators who are present at, and instrumental in, furthering the violence in different sites of SARV. One interviewee stated:

We haven’t burnt this type of woman here, that was the first time in Semin village. That is why we needed an expert to burn a woman with an evil spirit in her. So we got this man to come ... because he has a reputation for knowing how to torture such women.

The second type of contagion entrepreneur is the abovementioned glasman, called upon to identify the sanguma at work in a particular community. Glasman tend to come from outside the province, or are Engans who have spent significant time outside the province (Pupu and Wiessner 2018), which lends them the authority of foreign expertise needed to manage an introduced problem. A glasman was involved in 30% of our recorded cases. Glasman use a variety of tricks that vary from place to place, such as ‘finding’ incriminating objects on those accused, or ‘seeing’ the accused in a vision. In 2018, Enga police arrested a glasman behind several recent SARV acts; reportedly, he had attended funerals to generate business for himself by offering families to find out who had killed their relative. The police stated, ‘as a result of his “identification” ... two women were tortured over an open fire by their own tribesmen and women on March 1, resulting in the death of one about 11 pm on March 8’ (Post Courier 2018). An interviewee spoke of a glasman in the Tsak valley who terrorised the community by declaring ‘there are two sanguma women in every tribe in Tsak, so keep your eyes open’.

Glasman often receive money or other valuables for their services. In our study, they were paid in 90% of the cases they were involved with and in 10%, they received non-financial benefits. Reflecting on the role of the glasman and their motivation for identifying sanguma, a senior Enga police officer said:

Well he’s just glasman who goes around you know in other parts pretending to be a guy that is telling the truth of this sorcery, then he seems to be making a lot of money to be brought in to say: ‘look who did this’, you know sorcery accusation, to have had it pinpointed. So this glasman is coming as a person saying that he’s this such person or such lady or this had done this and that ... He’s creating additional false belief to the people.

Counter-contagion

Counter-contagion can be analysed through the same four-part framework as contagion. First, a range of narratives is used to counter both the sanguma narrative and the violent behaviour script. Counter-narratives are drawn from a range of different types of authority (Christianity, state, global human rights norms and Engan culture), such as: ‘You say you are a Christian’, ‘violence is against the law’, ‘she could be your sister’, ‘sanguma beliefs are not part of our culture’, and ‘everyone has the right to life’. Second, the population’s susceptibility to counter-narratives seems to require community insiders acting as doorways through which counter-narratives can be interpreted and acted upon. This supports Best et al.’s (2016: 119) findings in the context of social network support for long-term recovery from drug and alcohol addiction that ‘individuals are only likely to take on board the values, goals, messages and support from networks of people with whom they can already identify’. The more insiders there are, and the more influential they are, the more likely that counter-narratives will have an impact, reducing both accusations and violence. Our incident database shows that when more people intervene in an incident involving an accusation, the less likely the incident is to become violent.

Third, the narratives of counter-contagion are transmitted through the actions of multiple individuals/institutions working together in semi-formalised networks. These networks are highly relational, personal and contingent, involving survivors, individual police, NGOs, village leaders, church leaders and family members of those accused. A key figure involved in counter-contagion of SARV in Enga reflected:

My understanding of how these ‘interventions’ happen is that it’s a chain reaction. So someone has to initiate it, and know who to call, and have a telephone, and units, and gumption. And whoever they call has to pick up the call, and know who to call. A version of this must happen in the village, among the family, community, pastor, etc. Someone has to be the first one to speak. And then someone else either does or does not endorse that new narrative. Once the news gets to an authority figure, perhaps the contra-contagion has already gained some critical mass and all it needs is a trigger (an authority figure stepping forward to speak, say) and the violence is averted.

Public performance is an important mechanism of transmission for these counter-SARV narratives. For example, in November 2018, a campaign to spread clear and certain messages against SARV was initiated by key Engan leaders. At the launch of ‘Enga Says No’, the provincial police commander and provincial governor stood together to publicly declare that sorcery accusations and violence were ‘nonsense’, and violence would not be tolerated.[10] In another example, a seminarian attended the scene of a SARV incident and publicly told the crowd, ‘Now I will tell this lady to take my heart. If she can take my heart and I die, then people can prove that sanguma is real’. He surrendered to her and asked her to take his heart, stopping the violence.

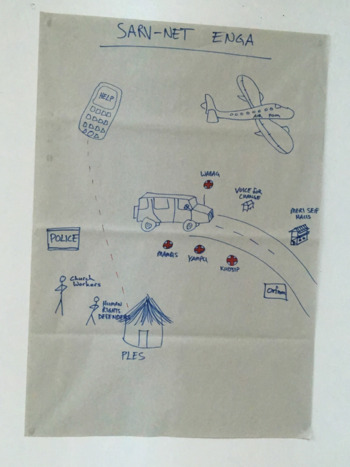

Counter-contagion entrepreneurs are a broad range of individuals and organisations within and external to Enga. Work to protect those accused from violence, or to intervene when violence has erupted, happens through an informal network involving a Lutheran missionary, community activists known as human rights defenders, a Catholic youth leader, a Catholic priest and two senior police officers. Occasionally, certain officers in the Department of Justice and Attorney-General are enrolled to organise further support and urge justice agencies to intervene appropriately. Figure 3 shows how this network was spontaneously pictorially represented by attendees at a 2018 SARV workshop, showing police, human rights defenders, NGOs (Voice for Change, Oxfam), church workers, hospitals and the ‘safe house’, all linked by the ambulance (road), mobile telephone (communications) and a plane (evacuations).

Figure 5: Pictorial representation of SARV network from SARV Workshop 2018.

Conclusion

We have argued that the theory of contagion of violence can be developed through use of a framework comprising four main components: (1) narratives of contagion, together with a behavioural script about use of violence as a response to the narrative; (2) population susceptibility to these narratives, in particular the role of worldviews and the relevant emotional landscape; (3) mechanisms of transmission, including physical and online social networks, public displays of violence and participation in violence; and (4) the role of contagion entrepreneurs. We have shown how this same four-component approach can be used to analyse the operation of counter-contagion initiatives in affected societies.

Several important preventive implications arise from recognition of the role of social contagion of SARV. First, it means paying attention to the mechanisms of contagion and how to counter them. The spread of sanguma narratives could be addressed by police targeting glasman, and addressing the confusion surrounding sanguma and the appropriate response to it through consistent messaging and leadership from public leaders, officials, community and faith leaders. A suggested intervention would be a campaign with clear and certain messaging, advocating non-violent responses to concerns about sanguma; this campaign would utilise arguments drawn from a mixture of legal, Christian and recognition-of-human-suffering frameworks. Second, it is vital to facilitate and encourage new social norms that lead to non-violent responses to accusations and the suppression of accusations themselves. Third, including contagion in addition to the existing focus on structural factors, such as poor health and poor education, highlights the importance of both monitoring incidents of SARV and seeking to counter the contagion of violence through targeting the particular narratives and contagion entrepreneurs.

Our data may be about violence connected to sorcery in one small part of the world. Yet, we suggest there is much value in pondering the virtue of Arthur Miller’s message in his depiction of ‘witch-hunting’ in The Crucible, that the shock of ‘the exotic’ for contemporary Westerners may help parse the morphology of ‘routine violence’. Narratives of contagion and behavioural scripts of the mundane kind, such as failing to invoke the apology script after bumping into someone’s drinks and instead responding violently (Polk 1994) sit alongside the more emotive and explosive landscapes of contagion and counter-contagion in a contemporary world. In contexts that enable contagious reactivity, like the virtual world and politicking, transmission of narratives of fear and hate is all too commonplace, and self-styled moral crusader contagion entrepreneurs curate hate-filled online content against those they have ‘othered’. As in Stan Cohen’s (1980) Folk Devils and Moral Panics, such ageless mundane dynamics of violence can be observed more sharply through the lens of moral panics elsewhere.

Acknowledgment

This research is supported by the Australian Government in partnership with the Government of Papua New Guinea as part of the Pacific Women Shaping Pacific Development program. The authors are deeply grateful for the feedback and suggestions by professor John Braithwaite, Professor Susanne Karstedt and Professor David Best.

ABC Pacific Beat (2017) Sorcery-related violence surges in PNG as women attached and murdered, accused of witchcraft. ABC News, 29 October. Available at www.abc.net.au/news/2017-10-29/png-upsurge-in-sorcery-related-violence/9095894 (accessed 10 September 2019).

Ashforth A (2002) An epidemic of witchcraft? The implications of AIDS for the post-apartheid state. African Studies 61: 121–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/00020180220140109

Bandura A (1973) Aggression: A Social Learning Analysis. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Berkowitz L (1973) Studies of the contagion of violence. In Hirsch H and Perry D C (eds) Violence as Politics: A Series of Original Essays: 41–51. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Best D, Beckwith M, Haslam C, Jetten J, Mawson E and Lubman DI (2016) Overcoming alcohol and other drug addiction as a process of social identity transition: The social identity model of recovery. Addiction Research and Theory 24(2): 111–123. https://doi.org/10.3109/16066359.2015.1075980

Black D (2011) Moral Time. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bowden R (1987) Sorcery, illness, and control in Kwoma society. In Stephen M (ed.) Sorcerer and Witch in Melanesia: 138–208. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

Braithwaite J and D’Costa B (2018) Cascades of Violence: War, Crime and Peacebuilding across South Asia. Canberra: ANU Press.

Buhaug H and Skrede Gleditsch K (2008) Contagion or confusion? Why conflicts cluster in space. International Studies Quarterly 52(2): 215–233. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2008.00499.x

Carcach C, Mouzos J and Grabosky P (2002) The mass murder as quasi-experiment: The impact of the 1996 Port Arthur Massacre. Homicide Studies 6(2): 109–127. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1088767902006002002

Cohen S (1980) Folk Devils and Moral Panics: The Creation of the Mods and Rockers. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press.

Comaroff J and Comaroff J (1993) Modernity and Its Malcontents. Ritual and Power in Postcolonial Africa. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Comaroff J and Comaroff J (1999) Occult economies and the violence of abstraction: Notes from the South African postcolony. American Ethnologist 26(2): 279–303. https://doi.org/10.1525/ae.1999.26.2.279

Constitutional Law Reform Commission of PNG (2012) Review of the law on sorcery and sorcery related killings. (copy on file with author)

Department of National Planning and Monitoring (2015) Millennium Development Goals 2015: Summary Report for Papua New Guinea. Available at http://www.pg.undp.org/content/papua_new_guinea/en/home/library/millennium-development-goals-final-summary-report-2015.html (accessed 10 September 2019).

Di Salvatore J (2018) Does criminal violence spread? Contagion and counter-contagion mechanisms of piracy. Political Geography 66:14–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2018.07.004

Erikson K (1966) Wayward Puritans: A Study in the Sociology of Deviance. New York, NY: Wiley.

Evans-Pritchard E (1937) Witchcraft, Oracles and Magic Among the Azande. London: Oxford University Press.

Fagan J, Wilkinson DL and Davies G (2007) Social contagion of violence. In Flannery D J, Vazsonyi A T and Waldman I D (eds) The Cambridge Handbook of Violent Behaviour: 688–723. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fernandes A (2014) A War on Witches/101 East, Al Jazeera. YouTube, May 2, 2014. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PeNn_Kh7Qmc (accessed 1 November 2019).

Fisman R and Miguel E (2008) Economic Gangsters: Violence, Corruption, and the Poverty of Nations. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Forsyth M (2016) The regulation of witchcraft and sorcery practices and beliefs. Annual Review of Law and Social Science 12. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110615-084600

Forsyth M, Putt J, Bouhours T and Bouhours B (2017) Sorcery accusation related violence in Papua New Guinea part 1: Questions and methodology. In Brief 2017/28, Available at http://dpa.bellschool.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/publications/attachments/2017-11/ib-2017-28_forsyth-et-al.pdf. (Accessed 18 October 2019).

Forsyth M, Gibbs P, Hukula F, Putt J, Munau L and Losoncz I (2019) Ten Preliminary Findings Concerning Sorcery Accusation-Related Violence in Papua New Guinea (March 27, 2019). Development Policy Centre Discussion Paper No. 80. Available at https://ssrn.com/abstract=3360817 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3360817 (Accessed 18 October 2019).

Fowler JH and Christakis NA (2010) Cooperative behavior cascades in human social networks. PNAS 107(12): 5334–5338. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0913149107

Fujii L-A (forthcoming) Showtime: The Logic and Power of Violent Displays. Available at http://duckofminerva.com/2018/03/remembering-lee-ann-fujii-a-friend-and-a-fighter.html (accessed 9 September 2019).

Geschiere P (1997) The Modernity of Witchcraft. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press.

Geschiere P (2016) Witchcraft and the dangers of intimacy: Africa and Europe. In Kounine L and Ostling M (eds) Emotions in the History of Witchcraft: 213–230. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gibbs P (2005) ‘You have a baby and I’ll climb a tree’: Gender relations perceived through Enga proverbs and sayings about women. Catalyst 35 (1): 15–33.

Gibbs P (2012) Engendered violence and witch-killing in Simbu. In Brewer C, Jolly M and Stewart C (eds) Engendering Violence in Papua New Guinea. Canberra: ANU Press.

Gibbs P (2016) I could be the last man—changing masculinities in Enga Society. The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology 17(3–4): 324–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/14442213.2016.1179783

Green B, Horel T and Papachristos AV (2017) Modeling contagion through social networks to explain and predict gunshot violence in Chicago, 2006 to 2014. JAMA Internal Medicine 177(3): 326–333. DOI: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8245

Haley N (2001) Impact of the 1997 drought in the Hewa Area of Southern Highlands Province. In Bourke R M, Allen B and Salisbury J G (eds) Papua New Guinea Food and Nutrition 2000 Conference: 168–169. Canberra: ACIAR.

HRC (Human Rights Council) (2009) Promotion and Protection of all Human Rights, Civil, Political, Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, Including the Right to Development: Report of the Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions. United Nations General Assembly. A/HRC/11/2. Available at https://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/hrcouncil/docs/11session/a.hrc.11.2.pdf (accessed 10 September 2019).

Huesmann LR and Kirwil L (2007) Why observing violence increases the risk of violent behavior by the observer. In Flannery DJ, Vazsony A and Waldman ID (eds) The Cambridge Handbook of Violent Behaviour: 545–570. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hutton R (2004) Anthropological and historical approaches to witchcraft: Potential for a new collaboration? The Historical Journal 47(2): 413–434.

Hutton R (2017) The Witch: A History of Fear, From Ancient Times to the Present. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Institute of Medicine and National Research Council (2013) Contagion of Violence: Workshop Summary. Washington: The National Academies Press. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24649515 (accessed 10 September 2019).

Lacey R (1978) Enga province, a general survey. Yagl-Ambu: Papua New Guinea Journal of the Social Sciences and Humanities 5(2): 164–178.

Lakhani S and Willman AM (2014) Trends in Crime and Violence in Papua New Guinea (English). Research and Dialogue Series, no. 1. Washington, DC: World Bank Group.

Landes WM (1978) An economic study of US aircraft hijacking, 1961– 76. Journal of Law and Economics 21: 1–31.

Lawrence S-E (2015) Witchcraft, sorcery, violence: Matrilineal and decolonial reflections. In Forsyth M and Eves R (eds) Talking it Through: Responses to Sorcery and Witchcraft Beliefs and Practices in Melanesia: 55–74. Canberra: ANU Press.

Losoncz I, Forsyth M and Putt J (2019) Innovative data collection and integration to investigate sorcery accusation related violence in Papua New Guinea. Qualitative and Multi-Method Research (forthcoming).

Markle DT (2010) The magic that binds us: Magical thinking and inclusive fitness. Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology 4(1): 18–33. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0099304

Marwick M (ed) (1970) Witchcraft and Sorcery: Selected Readings. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin Books.

Meggitt MJ (1981) Sorcery and social change among the Mae Enga of Papua New Guinea. Social Analysis 8: 28–41.

Miguel E (2005) Poverty and witch killing. Review of Economic Studies 72(4): 1153–1172. https://doi.org/10.1111/0034-6527.00365

Nguyen S and Rosengren K (2004) A causal reasoning about illness: A comparison between European and Vietnamese-American children. Journal of Cognition and Culture 4(1): 51–78. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1163/156853704323074750

Papua New Guinea Post Courier (2018) ‘Glassman’ involved in sorcery related killings arrested. Post Courier, 14 March. Available at https://postcourier.com.pg/glassman-involved-sorcery-related-killings-arrested/ (accessed 10 September 2019).

Peake G and Dinnen S (2014) Police development in Papua New Guinea: The need for innovation. Security Challenges 10(2): 33–57.

PNG TV (2018) Sorcery Cases in Enga Province. Facebook, Available at https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=2016268968388773 (accessed 1 November 2019).

Polk K (1994) When Men Kill: Scenarios of Masculine Violence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pupu N and Wiessner P (2018) The Challenges of Village Courts and Operation Mekim Save among the Enga of Papua New Guinea Today: A View From The Inside. Canberra: ANU Department of Pacific Affairs. Available at http://bellschool.anu.edu.au/experts-publications/publications/6233/dp-201801-challenges-village-courts-and-operation-mekim-save (accessed 10 September 2019).

Rosengren K and Hickling A (2000) Metamorphosis and magic: The development of children’s thinking about possible events and plausible mechanisms. In Rosengren K K S, Johnson C and Harris P (eds) Imagining the Impossible: Children’s Thinking About Magic, Science, and Religion: 75–98. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Siegel J (2006) Naming the Witch. Stanford, CT: Stanford University Press.

Stopsorceryviolence.org (2019) Stop Sorcery Violence in PNG. Available at http://www.stopsorceryviolence.org/ (accessed 21 October 2019).

Strathern A and Stewart PJ (2012) Peace-Making and the Imagination: Papua New Guinea Perspectives. Brisbane: University of Queensland Press.

Subbotsky E (2018) Science and Magic in the Modern World: Psychological Perspectives on Living with the Supernatural. London: Routledge.

Suwamaru JK (2014) Impact of Mobile Phone Usage in Papua New Guinea. Canberra: ANU Department of Pacific Affairs. Available at: https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/bitstream/1885/143350/1/IB-2014-41-Suwamaru-ONLINE_0.pdf (accessed 10 September 2019).

Towers S, Gomez-Lievano A, Khan M, Mubayi A and Castillo-Chavez C (2015) Contagion in mass killings and school shootings. PLoS One; San Francisco 10(7): e0117259. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0117259

Vyse S (1997) Believing in Magic: the Psychology of Superstition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Watson AH and Duffield LR (2016) From Garamut to mobile phone: Communication change in rural Papua New Guinea. Mobile Media & Communication 4(2): 270–287. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F2050157915622658

West H (2001) Sorcery of Construction and Socialist Modernization: Ways of Understanding Power in Postcolonial Mozambique. American Ethnologist 28(1): 119-150. https://doi.org/10.1525/ae.2001.28.1.119

WHRIN (Witchcraft and Human Rights Network) (2017) Witchcraft Accusation and Persecution: Muti Murders and Human Sacrifice: Harmful Beliefs and Practices Behind a Global Crisis in Human Rights. Available at: http://www.whrin.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/2017-UNREPORT-final.pdf (accessed 10 September 2019).

Wiessner P, Minape R and Maso Malala L (2016) A Teacher’s Guide for the Enga Cultural Education Pilot Programme. Port Moresby: Birdwing.

Zocca F (ed.) (2009) Sanguma in paradise: Sorcery, witchcraft and Christianity in Papua New Guinea. Goroka: Melanesian Institute.

State v John Kakiwi (2018) PGNC 273

[1] According to Hutton’s review of witchcraft across history and continents, only two other documented cases of a society with no traditional fear of witchcraft acquiring it exist, one in Tanzania, the other in Alaska (Hutton 2017: 37).

[2] This paper focuses on harm caused by those using sorcery, but we also acknowledge the rich heritage of healing, gardening and other forms of positive magic. As Salmah Eva-Lina Lawrence (2015: 69) insightfully observes, ‘[w]itchcraft and sorcery form part of the cultural terrain and indigenous knowledges of PNG’.

[3] Population growth has been phenomenal in recent decades. The 1980 census revealed a total population of 165,000, which increased to 432,035 in the 2012 census (Wiessner, Minape and Maso Malala 2016).

[4] One such case occurred in the late 1970s, proceeding to the Supreme Court: State v Unamae Aumane & Ors [1980] P.N.G.L.R. 510 (Supreme Court).

[5] SARV had occurred before 2010 on the fringes of Enga, particularly among the non-Enga. Unlike many places in PNG, the province largely comprises a single linguistic-cultural block, the Enga.

[6] Public statement by Enga Provincial Government, Office of the Governor 17 November 2017, http://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-11-20/girl-brutally-tortured-in-png-after-accusations-of-sorcery/9168876.