|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy |

Capital Punishment in Singapore: A Critical Analysis of State Justifications From 2004 to 2018

Monash University, Australia

|

Abstract

This article examines state justifications for capital punishment in

Singapore. Singapore is a unique case study because capital punishment

has

largely been legitimised and justified by state officials. It illustrates how

Singapore justifies capital punishment by analysing

official discourse.

Discussion will focus on the

government’s[1] narrative on

capital punishment, which has been primarily directed against drug trafficking.

Discussion will focus on Singapore’s

death penalty regime and associated

official discourse that seeks to justify state power to exercise such penalties,

rather than

the ethics and proportionality of capital punishment towards

drug-related crimes. Critical analysis from a criminological perspective

adds to

the growing body of literature that seeks to conceptualise social and political

phenomena in South-East Asia.

Keywords

Communitarianism; death penalty; justification; legitimacy; state power;

war on drugs.

|

Please cite this article as:

Yap A and Tan SJ (2020) Capital punishment in Singapore: A critical analysis of state justifications from 2004 to 2018. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 9(2): 133-151. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.v9i2.1056

![]() This

work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution

4.0 International Licence. As an open access journal, articles are free to

use with proper attribution. ISSN: 2202-8005

This

work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution

4.0 International Licence. As an open access journal, articles are free to

use with proper attribution. ISSN: 2202-8005

Since the late 1980s, there has been a concerted movement against the mandatory imposition of capital punishment and more broadly, its complete abolition as a form of punishment (Hood and Hoyle 2017). To date, 104 countries have abolished the death penalty, while approximately 160 others are abolitionist in policy or practice. Only 54 countries maintain an active-retentionist status (Amnesty International 2016). This means that 53 and 82 per cent of countries across the world are now abolitionist in policy and practice respectively. This shift was motivated by a variety of factors, including humanitarian and religious reasoning, and state compliance with international standards (Bae 2008; Hood and Hoyle 2017). International conventions, protocols and tribunals have sufficiently demonstrated that capital punishment is no longer regarded as a legitimate sanction against any crimes (Bae 2008; Lehrfreund 2013). This practice, however, is not enshrined as illegal under international law, unlike the practice of torture, which is illegal and prohibited under the Geneva Conventions of 1949 (Geneva 111) and additional protocols (e.g. Protocol 1) on 8 June 1977.

Singapore remains one of the few countries that maintains an active-retentionist approach, despite emergent international consensus against the use of capital punishment. Application of the death penalty is an integral part of the state’s penal regime, with long-drop hanging serving as the preferred method of execution (Arora 2016; Boo 2016; Tippet 2005). Cases of execution are also regularly featured in official and media discourse to reiterate the state’s strict approach towards crime control. Singapore was once described as the ‘world execution capital’ because its execution rate was nearly twice as high as China’s during the mid-1990s (Johnson and Zimring 2009, 264, 408) and had the second highest per-capita execution rate in the world from 1994–1998 ((United Nations Office on Drug and Crime 2001; 17)). During this period, the execution risk for murder in Singapore was also 24 times that of Texas, the state with the highest execution rate in the United States (US) (Zimring, Fagan and Johnson 2010). It also executed as many people (76) as Japan between 1978 and 2007, even though Japan has a population 30 times larger than that of Singapore (Zimring, Fagan and Johnson 2010).

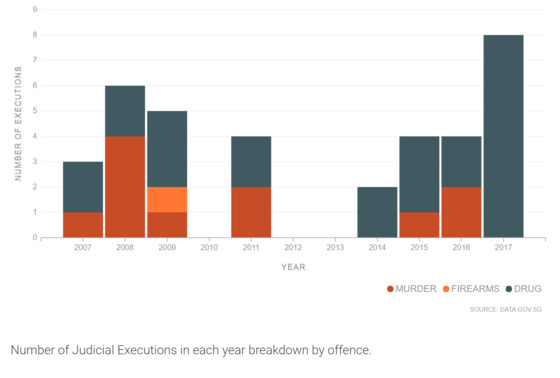

Singapore is one of the four Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) states to have carried out executions in the last five years for drug-related offences,[2] with 15 of its 18 executions for drug-related offences (2013–2017, Ministry of Home Affairs 2017; see Figure 2).[3] Most of those executed for drug offences also appeared to be foreign nationals, predominantly from Malaysia, although this has been disputed by the state (Amnesty International 2004; Singapore government 2004).[4] This also frames the symbolic importance of the death penalty in Singapore, as the state presents itself as a well-ordered, clean and pure society (see Lee 2000; Quah 2009; Rajah 2014 for Singapore’s state nation-making project of becoming and staying ‘clean’; see also Hacking 2003 for management of polluting and defiling risks), in comparison to its neighbours. Application of the death penalty is consistently and actively extolled as an effective deterrence to drug-related crimes and low rates of drug use in Singapore within official discourse (Ministry of Law 2009; Ministry of Law 2012; Singapore government 2004). Certain events, such as the marked decline in (publicly released) execution figures, amendments to the Penal Code and Misuse of Drugs Act (MDA) in 2012, which provided minor concessions to its mandatory nature, and a shift in prosecutorial decisions, have led scholars to suggest that there may be eventual policy reform in the direction of abolition (Johnson 2013).

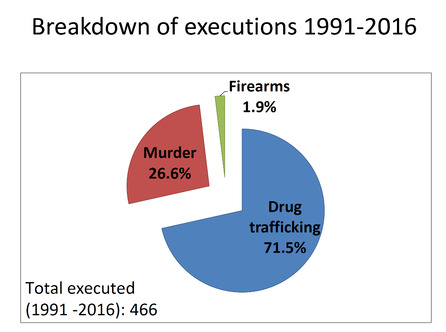

Figure 1: Breakdown of Executions 1991-2016 (Chan 2017)

Figure 2: Annual Breakdown of Judicial Executions from 2007–2016. Source: Ministry of Home Affairs (2018)

Conversely, others have asserted that without fundamental changes to the orientation and beliefs of political elites, change is unlikely (Bae 2008; Chan 2016; Chen 2015; Johnson and Zimring 2009). This assertion is supported by the Singaporean judiciary, which expressly communicated that modifying or repealing this legislation is not within its prerogative, as capital punishment is not in breach of the Singapore Constitution (Lehrfreund 2013; Tey 2010; Thio 2004). The appropriateness or suitability of the death penalty as a form of punishment is understood by the Singaporean judiciary as a policy matter that falls under the purview of the Parliament, rather than a legislative matter for the courts to decide (see Yong Vui Kong v PP judgement, para 122).

If political willpower is the central denominator for reform, this article contends that there is a need to consider how the Singapore government cultivates and sustains the legitimacy of capital punishment through official discourse and state narrative. Therefore, this article seeks to understand how the state justifies capital punishment to local and international stakeholders. Past studies on Singapore’s application of capital punishment have focused on the defining characteristics of the system, its socio-legal impacts, various legislative changes, and interpretation by prosecutors and the courts (see Chan 2016; Chen 2015; Hor 2004; Tey 2010). This article has instead chosen to reframe discussion around a critical qualitative approach that interrogates the interactive nature of state power. This is accomplished by combining examination of state rationale through sociological theory situated in domestic context (Chua 1995; see also Tan 2000), with broader international understandings of punishment (see John Pratt’s work for example). Although international understandings were mainly developed to understand Anglophone societies, this body of work was selected as it illuminates social implications of punishment through a critical lens, an aspect lacking in understandings of South-East Asian states more generally and Singaporean scholarship in particular (Rajah 2012). Critical analysis of capital punishment discourse complicates how think about the state’s law-making and adjudication power. Singapore is an ideal case study for this purpose, as its regime has been characterised across the spectrum of democracy and despotism (Chua 1995; Rajah 2012, 8). Most significantly, examination of the state’s official discourse could also indicate shifts and larger decision-making processes in Southern/Asian states, given that it is the chair of the ASEAN committee and a leader in economic and political development within the region. The presentation of political dynamics in this case study emphasises the fundamental role of politics of legitimacy in Asia.

Singapore’s ‘aggressive death penalty system’ (Johnson 2010, 338) is the cornerstone of the state’s ‘zero-tolerance’, ‘tough on crime’ and ‘strong anti-drugs’ penal regime (Lye 2015; Shanmugam 2009, 2012a, b, 2014, 2016). It also forms a key part of Singapore’s larger crime control framework, which is grounded on principles of prevention, deterrence, retribution and rehabilitation (see Menon 2017). Over the last 15 years, the Singapore government has consistently and publicly reaffirmed its tough stance on crime across various domestic and international platforms.

State officials have articulated that the retention and application of capital punishment is rational, relevant and imperative for the preservation of wider national interests, such as security, order and social stability (Lye 2015; Shanmugam 2016, 2017a, b). The government justifies its stance on the basis that capital punishment is part of its broader ‘tough law and order system’ (Singapore government 2004; Shanmugam 2009, 2014, 2017), which is conceived to play an essential and effective role in keeping the nation a ‘drug-free zone’ (Lye 2015; Ministry of Law 2012; Shanmugam 2016, 2017a). This discourse also reflects the state’s response to drug-related offending, where corporal and capital punishment is made available for drug use and/or possession, and distribution under the MDA. Available statistics from 1991–2016 indicate that drug-related offences have constituted most (71.5 per cent) of death penalty sentences (see Figures 1 and 2).[5] This is notwithstanding the fact that many other criminal behaviours, such as crimes against the president’s person, piracy, perjury, abetting the suicide of minor or an ‘insane’ person and kidnapping are also capital offences (Penal Code of Singapore 2012).

Capital punishment in Singapore stems from colonial British rule, consciously retained by the newly elected government following independence in 1965 (Hor 2004). This practice aligns with the PAP government’s patterns of governance, as it has proven to be quick to translate historical conditions conceptually beyond colonialism into its thematised ‘ideology of survival’ (Chua 1995, 18). The state has built on British structures in the sector of law and punishment by extending its use of the ‘shell of the Westminster system’ (Austin 1987, 283; Baxi 2000; Bhabha 1994; Brown 2017; Kumarasingham 2016; Rajah 2014, 140; Turnbull 2009). Capital punishment is not only inherited, but extended to ensure the survival of a newly independent nation-state that is conceived to be ‘particularly vulnerable to drug menace’ due to its close geographical proximity to the Golden Triangle (emphasis added, Singapore government 2004; see also PMS 2016; Shanmugam 2009, 2014, 2016, 2017).

Capital punishment was extended to drug-related offences in 1973 under the MDA (Act 5 of 1973)[6] and was made mandatory for drug offences in 1975 to provide a ‘necessary deterrence to drug traffickers and pushers’ (Chong 2016). It aimed to deter the import and use of illicit drugs. The government’s move to widen the practice of capital punishment was framed as a legitimate act, with policymakers arguing that it would protect the nation from the ‘looming threat’ of drug-related crimes during its early years of independence[7]. Chua Sian Chin, the then-minister for home affairs, cited an increase in the number of traffickers and financiers as a key rationale for expanding the application of the death penalty, stating that, ‘unless trafficking and drug addiction are checked, they will threaten our national security and viability. To do this, both punitive and preventive measures must be taken’ (emphasis added, Parliamentary Debates 1977). In this instance, the extension of punishment frameworks was done amid what the state considered ‘alarming’ and ‘epidemic’ proportions of drug use (Abdullah 2005, 50).

The rate of drug use increased substantially following the introduction of the MDA, although heroin use and the fear of a ‘social scourge’ was cited as the primary target for passing more punitive policy (CNB 2002, 2015, 2016; Lai 1975; SANA 2018). Heroin use was first identified in 1972 with only four cases (0.1 per cent) of arrests. It quickly surged from 10 cases (0.3 per cent) in 1973, to 110 cases (3.4 per cent) in 1974, and 2,263 (53.9 per cent) in 1975; 1975 marked the beginning of the heroin ‘epidemic’. Since then, heroin use has dominated the drug scene, with percentages of the total numbers arrested for drug use fluctuating between 68 and 95 per cent (Abdullah 2005, 52). Drug-related crime has not dropped below 3,000 since 1976 (Abdullah 2005, 52). Nevertheless, the government attributes its tough approach as a contributing factor for the ‘successful control’ of the drug situation (Ministry of Law 2010; Shanmugam 2014, 2017; Singapore government 2004).

This increase in drug-related crime could also be attributed to an increase in policing efforts rather than an actual increase in drug-related crime. In this instance, Singapore, like other societies in the 1970s, spiralled into an ‘age of anxiety’, due to uncertainties and insecurities brought on by social and economic restructuring (Pratt and Eriksson 2013, 165). This is pertinent to the case of Singapore as the state was stepping into its first decade of independence under PAP leadership and a relatively inexperienced participant in the global economy.

The decision to enact such a strong punishment stems from the need to display force in unstable political–moral order. Here, capital punishment comprises part of the state’s tough, punitive and reactionary system that is conceived by the leadership as a measure to manage literal and constructed notions of risk under notions of ‘survival’ (see Hacking 2003, 23, 28), which are repeatedly thematised discursively by political leaders and citizens (Chua 1995, 19), further rationalising such repressive interventions. Drugs[8] are periodically constructed as serious ‘threats’ or ‘problems’ (Ministry of Law 2012; PMS 2016; Shanmugam 2012a, b, c), with the potential to ‘destroy’ lives (Shanmugam 2014), justifying tough, unpopular and repressive state interventions (Shanmugam 2012c). The state has ‘no choice’ but to enact to ‘ensure [the paramount importance of] (our) citizens’ fundamental human right to safety and security’ (PMS 2016; see Chua 1995, 20–21). Enactment of strong punitive approaches towards the risky nature of drugs is not only a symbolic denouncement of illicit drug use and distribution in more ‘drug-tolerant’ Western societies. It is part of a larger framework in which the government actively paints Western values as undesirable. The state retains ‘Asian values’, while affirming a ‘drug-free’ society at the same time. This is constructed under Asian communitarian ideology to achieve global economic advancement through a highly disciplined domestic workforce.[9]

The Singapore government continues to justify its need to retain capital punishment four decades from its extension for drug trafficking. Such justifications are based on communitarian ideals, as Singaporeans are encouraged to place the ‘nation before community and society above self’ and uphold ‘shared (Asian) values’ (Chua 1995, 32–34). Here, communitarian ideals legitimise the sacrifice of individual rights and the rights of offenders, to ‘effectively’ manage the ‘drug problem’ and ensure that Singapore does not become ‘washed over with drugs’ (Ministry of Law 2009; Shanmugam 2014, 2016; Singapore government 2004). The ‘drug problem’ is framed as a ‘threat’ to national security and safety in official discourse. In turn, Singapore citizens are constructed as potential victims (PMS 2016; Shanmugam 2012c, 2014):

Capital punishment continues to be used to deter what we consider to be the most serious crimes, in terms of their impact on the immediate and third-party victims, as well as society at large, and this includes crimes like drug trafficking and murder. (emphasis added, PMS 2016)

Deterrence of crime, specifically, drug-related crimes, is adopted as a legitimising discourse to justify Singapore’s continued need for capital punishment in an era when most countries appear to be moving towards abolishment of the death penalty. The state argues that the mandatory execution of drug traffickers significantly bolsters crime control efforts, as the ‘looming threat of death’, efficient enforcement and surety of punishment effectively deters potential criminals from making the ‘choice’ to traffic drugs into Singapore (Shanmugam 2014). In this instance, state perceptions and constructions of the ‘strength of deterrence’ also stems from the act of punishment in itself:

because of its [death penalty] finality, [it] is more feared than imprisonment as punishment. (emphasis added, Singapore government 2004, 5)

A lot of people know of our tough position. Given this knowledge, people are very, very cautious and trafficking in Singapore becomes a very risky business. (Shanmugam 2016)

Similar notions can also be identified in the United Kingdom Parliament's (1982) argument for the restoration of the death penalty, where ‘the power of punishment was used to unite communities through its expressive signs and symbols’. Like Singapore, this was done at the expense of (would-be) criminals ‘who are held responsible not just for their crimes, but for the way in which the world was losing its familiarity and security’ (Pratt and Eriksson 2013, 169).

Moreover, the deterrence effect of death penalty on crimes has been widely debated in criminological literature (Cloninger and Marchesini 2001; Ehrlich and Liu 1999; Mocan and Gittings 2003; Zimmerman 2004), with empirical studies concluding that this punishment has negligible effects on homicide rates (Zimring, Fagan and Johnson 2010),[10] and drug use (Degenhardt et al. 2008). Critics have also asserted that despite Singapore’s claims of effective deterrence and control, the government has rarely published reliable data on rates of drug use or drug-related crimes to allow any independent verification of those claims (HRI 2016; Lines 2018).

Conversely, the Central Narcotics Bureau’s report (2016) indicates that there has not only been an increase in new ‘drug abusers’, but also an increase in methamphetamine and cannabis seizures. Despite this inconsistency between policy justification and impact, the narrative of deterrence and its effectiveness in controlling drug crimes continues to be used by the state to legitimise capital punishment. Each amendment to the capital punishment policy has been justified on the basis that the death penalty is ‘necessary’ for the ‘continued effectiveness’ of Singapore’s anti-drugs laws (Chong 2016).

In the Singaporean context, deterrence provides an effective mechanism to legitimise the state’s administration of capital punishment primarily due to two intersecting factors. The first is a strict adherence to the ‘rule of law’. This is argued by Singapore Minister of Foreign Affairs Vivian Balakrishnan:

[The death penalty] is applied only and strictly in the context of an unwavering commitment to the rule of law ... Capital punishment is carried out only after due judicial process and in accordance with the law. (Balakrishnan 2016)

The emphasis that the death penalty is administered equally and consistently establishes that the punishment is a fair and expected outcome for drug trafficking (and serious offences) in Singapore. The legal validity of such penal power is used to justify the execution of drug traffickers. Here, international critics are assured that state powers are being exercised impartially, consistently and in accordance with pre-existing laws. Such emphasis also promotes the state’s image in the eyes of the public, as audiences are reminded of safeguards against miscarriages of justice, rationalising the fact that all offenders sentenced to death are unmistakably deserving of their punishment.

By pitting the imposition of capital punishment against ‘deserving’ offenders as an indispensable element for crime control, the state also creates an either-or situation, in which justice and protection is possible only through the execution and/or threat of execution. This exertion of penal power is framed as a matter of choice that the state has to make to ‘protect’ Singaporean families (Shanmugam 2014; see also PMS 2016).

It is not because we like the death penalty, it is not because we think it ought to be imposed for no reason, it is not because we want to simply be tough. It is imposed with the duty of ensuring the safety and security of every single Singaporean who goes out on the streets. We feel that there is no choice but to have this framework. (emphasis added, Shanmugam 2012c)

Across other platforms, state officials have reiterated that capital punishment is used as a last resort in ‘limited circumstances’ to ‘protect citizens from becoming victims’ especially in the face of evolving challenges, such as the potential influx of illicit drugs (Shanmugam 2017a; see also CNB 2002, 2003, 2016). In this manner, the focus is shifted from the punishment of offenders to the potential impact if offenders were not apprehended. The trope of national vulnerability is not unique to drug-related offending (see Chua 1995). ‘Crisis of survival’ is invoked periodically to revive legitimacy for repressive interventions (Devan and Heng 1992). This allows the state to justify a ‘tough’ and ‘strong’ criminal justice framework and marginalise individual rights to life. Continual construction of omnipresent threats (e.g., drugs, communism and terrorism) justifies the need for a strong legal and penal system that sidesteps individual rights for the sake of social stability.

Sacrifices for ‘The Greater Good’: Embedded Communitarian Ideals

Here, the notion of defending citizens and sacrificing the lives of guilty offenders forms the second trope of the state’s legitimising discourse. Such discourse aligns with communitarian ideology, in which a good government is one that ensures the wellbeing of the collective through a range of pre-emptive measures that may come at the expense of individual rights (Chua 1995, 187, 201). The state sacrifices individual rights to safeguard national safety and citizens’ rights to be free and safe from the polluting nature of drugs (see Hacking 2003). This punitive reaction must also be viewed in lieu of other pre-emptive measures enacted to maintain social discipline and ‘root out’ the corrupting and polluting nature of drugs through use of corporal punishment (under s 33 of the Misuse of Drugs Act). Capital punishment seeks to control and limit the supply of drugs by preventing and controlling the possibility of citizens being ‘corrupted’ or ‘damaged’ by drug consumption. Further, the state keeps outliers in line with the literal and symbolic act of flogging (Rajah 2014) under the rule of law to ensure adherence to ideological pillars of order, hygiene, discipline and moral fibre (Chua 1995; Heng 2008; Merry 2004).[11]

Additionally, the state, government and society are conflated under communitarian ideology, which relies heavily on the moral uprightness of leadership and its desire to uplift societal welfare (Chua 1995). This allows the Singapore government to justify the necessity of capital punishment and dismiss calls to recognise offenders’ rights as ‘misplaced sympathies’ (Shanmugam 2016, 2017; see Matthews 2005, 186). The rights of those who face execution is subordinated by the rights of citizens ‘to live in a safe, secure and drug-free environment’ (Ministry of Law 2012). The prioritisation of the ‘collective good’ (public and victim’s rights), over individual (drug offender) human rights is not an exceptional feature of the state’s penal order, but rather, a core component of Singapore’s approach to governance. The government has sought to establish a communitarian-based understanding to rights and obligations since the early days of independence (Barr 2000; Oehlers & Tarulevicz 2005; Tan 2000). As empathetically argued by Singapore’s first Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew (1990), ‘The basic difference in our approach springs from our traditional Asian value system, which places the interests of the community over and above that of the individual’. Under the ideological framework of collective security, the paramount consideration for the state is the maintenance of social stability and discipline to safeguard its capacity to fulfil overarching national objectives and interests (Barr 2000; Tan 2000).

This framework forms the implicit baseline against which capital punishment, and more broadly, other punitive legislation, can be legitimised by the state as a practical necessity in the name of law and order, national security and public morality. Importantly, this also allows the state to portray the criminal justice system as prioritising the protection of citizens (Menon 2017; see Pratt 2006a, 18; Pratt and Eriksson 2013, 173). Law Minister Shanmugam (2017) stated in his recent speech for the Asia Pacific Forum Against Drugs that:

We take a completely victim-centred approach in the sense that rehabilitation is the critical plan of our approach. For the abuser, we focus on rehabilitation and we are going to go even more down that road. The persons we focus on from a legal angle, very severely are the traffickers. Because they are the ones who ruin lives, the ones who do it for profit.

The legitimacy of penal powers in relation to capital punishment is further heightened by embracing a victim-centric approach, as it creates the perception that state officials are operating under a moral code. This is further exacerbated in the domestic context, in which citizens have been socialised to value substantive outcomes and effectiveness above all (Rajah 2012). The execution of drug traffickers may be more easily accepted by the public as legitimate without due consideration of the extraneous circumstances that led to their criminal behaviour, or implications of breaches of one’s right to life on the offender, his or her family and broader society.

The final trope that bolsters the state’s attempt to legitimise capital punishment is the constant reiteration of its effectiveness in safeguarding the safety and security of Singapore by keeping crime rates low and streets free from drugs. State officials have drawn on the government’s capacity to keep Singapore relatively free from ‘drug problems’ on more than one occasion. The ability to keep citizens safe from such serious crimes is associated with the power to enforce ‘tough laws’, namely, capital punishment. The following statements not only exemplify these notions, they highlight the consistency in these approaches since 2004:

Taking into account our national circumstances, we have made a considered decision to retain the death penalty. It has worked for us, making Singapore one of the safest places in the world to live and work in. (Singapore Government 2004, in response to Amnesty International’s report)

One of the main reasons that our society is probably one of the safest in the world is that we take a very tough approach on drugs. (Shanmugam 2014)

This creates a perception that the safety and security of Singapore is contingent on the presence of capital punishment, without which there would be an increased risk of an uncontrolled ‘drug situation’ and a city plagued by ‘druggies’ who will ‘accost citizens and/or children’ on public transport (Shanmugam 2017, 4).

Empirical studies have demonstrated that crime control and low crime rates are affected by a range of individual and socio-structural factors (Graif, Gladfelter and Matthews 2014; Sampson 1985), rather than the implementation of a punitive law. However, the state has sought to consolidate the perception that efficacy of Singapore’s criminal justice system has much to owe to capital punishment. By drawing a strong correlation between low crime rates and safety in public spaces with the death penalty, the state re-establishes the importance of this punishment with citizens. The politics of drug crime and punishment continues to be embedded in ideologically self-conscious interventionist state actions, despite the steady progression from communitarianism and survivalist ideals (Chua 1995, 210).

State and Public Interests Conflated Under Expressive Moral Acts

The study of capital punishment in Singapore has reflected embedded communitarian and survivalist ideals through the tropes of deterrence, national vulnerability, defence collective interests and the sacrifice of individual rights, with the latter two representing Asian and Western values respectively. Interestingly, expressive and utilitarian notions of punishment have also emerged since 2012 in response to growing criticism from international and human rights organisations. The state combines inwardly directed communitarian themes of justification with more expressive notions of punishment, largely made possible through dominant PAP leadership that has ‘assumed a strong leadership role, over and above expressions of public opinion’ (emphasis added, Pratt 2002, 31).

Since the imposition of capital punishment in Singapore is not reflective of the crime rate, it should be viewed as ‘an expressive form of moral action’ used to reassure ‘anxious and insecure communities’ (Garland 1990). Here, the performative act of capital and corporal punishment is used to unite the public against drug traffickers and users, who are constructed as obvious enemies that threaten the survival of the ‘young vulnerable’ (Ministry of Home Affairs 2012; Pratt and Eriksson 2013, 165; Shanmugam 2017). Bodies are disciplined and beaten into submission or eliminated, thus embedding symbolic punitive state expressions into the consciousness of citizenry. The political effect and long repressive shadow of state power can also be identified in the public denouncement of drug users through acts of caning and execution (see Chua 1995).

Moreover, Singapore relies on evidence produced by its own officials and experts (Lines 2018), as it continues punishment in accordance to its own values, rather than that of ‘the civilised world’ (Pratt 2002). The state uses its power to lead public opinion by reasserting the status of retention. This is accomplished by repeated assertions of legal validity[12] of state power to exercise capital punishment; the sovereignty of Singapore allows for self-validating discourse (Beetham 1991, 122). State power allows for self-determination of rules and enlarges government power through discourse on punishment, as the state exerts its authority and moral notions as it chooses to rather than to adhere to notions of human rights proposed by the larger ‘civilised world’ (Pratt 2002, 33).

Singapore, like other active-retentionist states (e.g., the US and Philippines), diverges from widely accepted ‘boundaries of punishment in the civilised world’ (Pratt 2002, 27). The economically and developmentally progressive state continues to hold offenders accountable for their actions through such punitive sanctions, while other societies[13] have progressed to abandon retribution and deterrence in favour of new philosophies of punishment, in which society has taken on responsibility for crime (Pratt 2002, 29–30). Here, the government satisfies its political interests of retaining and exerting its authority to exercise draconian forms of state power[14] and the legal validity of punishment policy and practice, as opposed to formulating penal policies in direct response to occurrences of crime. This is due largely to the fact that political and legal decisions have been made possible through the one-party government that has ruled Singapore since 1968 (Chua 1995, 40). Further embedding communitarianism ideals, the electorate is encouraged to trust and respect its democratically voted leadership’s decisions to uplift societal welfare over self-interest, especially in the face of repressive interventions that potentially abuse individual rights (Chua 1995, 187, 210).

This is in addition to the fact that the legal validity of state power to exercise capital punishment has been assumed to be a given by the current government in power, as its ability to decide on penal practices was conferred upon it by electoral success. In this instance, the government is perceived to exert its power through the use of capital punishment to ‘protect’ the public and potential victims. The added layer of communitarian ideology further shifts the focus from the rights of individuals to collective interests, in a state-conceived desire to preserve the moral uprightness of Asian values so that the welfare of the people is ensured. Anyone perceived to think differently or oppose interventions is discredited as selfish and not self-sacrificing (Chua 1995, 52).

It is also important to note the difference between being ‘seen’ to act on something, as opposed to genuine intent to address an issue effectively (Cunneen 2011, 14). This raises the question of whether the state is truly acting on self-serving or public serving interests (Pratt 2007). The lack of consideration of the ‘moods, sentiments and voices of significant and distinct segments of the public’ implies that the former appears to be true in this instance (original emphasis, Pratt 2007, 9). The government appears to be acting on behalf of the ‘silent majority’ in its exercise and discussion of the death penalty, despite the persistence of ‘voluble voices’[15] in such dialogues (Pratt 2007, 95).

More significantly, Singapore’s attempt to justify capital punishment in its official discourse[16] indicates that punishment is instrumental to the government’s expressive act, as it disseminates official signs and symbols of state willingness to exercise its sovereign power in a climate with inherent social and penal control. Each publicised ‘unpopular’ decision to flog or execute drug offenders is constructed as a good governmental decision to preserve ‘national survival’. Further, this act encourages social support for the execution of ‘obvious enemies’ who have the potential to pollute, corrupt and threaten ‘wholesome eastern traditions’ (Chua 1995, 187). Asian states, such as Singapore, continue to be contrasted with decadent drug-tolerant societies which have given in to international pressure to enact more lenient responses (Shanmugam 2016). What may be perceived by critics as over-anxious, over-reactionary and draconian use of state power to punish, is ideologically and culturally palatable within communitarianism and discursive constructions of ‘survival’ and ‘sacrifice’ for the greater good (Balakrishnan 2016).

Support, Dissent or Ambivalence?

All these repeated expressive notions allow the supposed ‘effective deterrence’ of capital punishment to be widely accepted by citizens (Reach 2016). Notwithstanding, the policy and practice of capital punishment has largely been a nonissue that has evoked little debate in the public arena (Oehlers and Tarulevicz 2005). Execution and the fundamental idea of capital punishment have remained largely unchallenged, apart from a few abolitionist advocates (see Conclusion). If such occurrences were taken at face value, one can easily assume that most Singaporeans consent to the death penalty as a legitimate form of punishment. Public surveys indicate that most citizens support the death penalty for intentional murder, trafficking, illegal drugs and discharging a firearm (Chan 2017; Reach 2016; Tan 2017). Support however, dropped considerably when respondents were asked to apply punishment in practical case examples. Support also dropped significantly, from 92 to 56 per cent, and 86 to 53 per cent for intentional murder and drug trafficking respectively, when participants were told that the death penalty is not more effective than life imprisonment. This highlights two key issues. First, the narrative of effective deterrence has a substantial impact on perceptions of state power to exercise the death penalty. Second, support for the death penalty in Singapore may be more nuanced than previously assumed (Chan et al. 2018).

The absence of pressure to abolish capital punishment leads one to assume that Singaporeans recognise this as a legitimate penal policy and appear to believe in the death penalty’s capacity to effectively deter drug-related activity.[17] It is also important to recognise that public discourse on the appropriateness and suitability of mandatory death penalty in Singapore has been largely absent (Leong 2008). For a long time, the dominant narrative promulgated across mainstream platforms was official discourse on deterrence, ‘deserving’ offenders as ‘obvious enemies’, and national vulnerability and survival. Capital punishment was also not popularly perceived as a relevant subject of daily conversation. Oehlers and Tarulevicz (2005) assert that discussion only assumes significance when Western democracies criticise Singapore. The controversy and debate in this case stems from the outrage of being criticised internationally for a domestic criminal justice issue,[18] as opposed to the administration of capital punishment per se (Leong 2008; Oehlers and Tarulevicz 2005).

Responding to Regional and International Audiences

In stark contrast to public silence in Singapore, capital punishment has attracted much attention on the international platform. Most dialogue from the international community is critical, and international organisations like the United Nations (UN), Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have consistently urged Singapore to abolish capital punishment. The state has sought to justify its actions in the face of such criticism by challenging the global movement towards abolition (Reus-Smit 2014). This is evident in state discourse over the last 15 years, as the government repeatedly emphasises the lack of ‘international consensus’ on the abolition of the death penalty (Balakrishnan 2016; Ministry of Law 2009; Shanmugam 2009; Singapore government 2004). A commonly evoked defence is that the choice to retain the death penalty as a form of punishment is Singapore’s sovereign right. Analysis of such expressions can also be understood through the communitarian framework (Chua 1995; Wang 1980). The state asserts its sovereign power to enact social and penal control by explicitly denouncing individualism on social and political platforms as a risk that could lead to declining economic competitiveness (Barr 2000; Chua 1995; see former Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong’s 1988 speech). Denouncement of individualism and individual rights to life in the case of capital punishment aligns with longstanding state narratives, as Western values of individualism and tolerance have long been dichotomised with Asian values by Singaporean leadership, with occasional concessions given to select Western values (Chua 1995, 32, 186; Lee 1989, 32; White Paper 1991, 1; Yeo 1992).

Additionally, Singapore has been one of the leading countries to vote against the moratorium on the use of death penalty at the UN General Assembly (Hood and Hoyle 2017), and has advocated for the retention of such practices since 2008. The state legitimises its retentionist position by defining its obligation to honour international human rights standards as an ‘exceptional’ responsibility, choosing to favour state-defined interests instead. The state’s emphasis in its resisting official discourse rests again on the lawfulness, fairness and effectiveness of the criminal justice system, with consistent adherence to the ‘rule of law’ for internal audiences. The ‘lack of international consensus’ and the ‘sovereign right’ to develop its own legal system form core contentions for the state’s global audience (Balakrishnan 2016; Ministry of Law 2009; Shanmugam 2009; Singapore government 2004). Minister for Law and Home Affairs Shanmugam (2017, 3) revalidated Singapore’s position, stating:

What they do not focus on are the thousands of people whose lives are ruined, whose families are ruined, and the undoubted number of deaths that will occur if you take a more liberal approach towards drugs. The rise in homicides, rise in crimes that lead to deaths, these are not theoretical arguments, you just look at the places where the drug situation has heightened, gotten out of control, or is less under control.

This statement was made in response to calls for a more liberal approach towards drug traffickers. Communitarianism can again be identified in international responses and re-emphasised in other contemporary justifications for capital punishment. Shanmugam (2016) reiterates collective interests and polarises control and regimental approaches with tolerance, and ‘relaxed’ and decadent approaches of the ‘West’:

The ASEAN position is that we will maintain a zero tolerance approach against drugs. We take this approach because we know the cost of failure is too high. If we fail, drugs will overwhelm our societies and destroy the lives of our people. If we let drugs take root in our societies, everything that we stand for will be threatened -our families, our social stability, our security ... we have and will continue to face a lot of international pressure to take a more relaxed approach, to be more tolerant ... I ask that we maintain our resolve in ASEAN and do what we know is best for our people. (emphasis added)

The Minister of Law went on to encourage the ASEAN 'collective' to remain strong and ‘keep this [resolve against drugs] up’. The problem of drugs is constructed as a threat and a growing problem that inflicts ‘irreversible damage’ (Shanmugam 2016). If left unchecked, Singapore runs the risk of being ‘overrun’ by drug syndicates (Shanmugam 2017). The leadership’s ‘vigilant’ resolve can be identified here, as it continues to operate under a survivalist mentality that executions are a necessary ‘right’ ‘for the people’ (White Paper 1991, 8; see Shanmugam 2016). Here, international pressure to adopt a more relaxed and tolerant approach is also conflated with Western decadence and rejected as South-East Asian states’ sovereign right to protect their societies and people from the ‘scourge of drug trafficking’ (Chong 2017; see Kok 2017). Thus, the state’s resolve to keep the community drug-free, as opposed to drug-tolerant (Lye 2015; Shanmugam 2016, 2017), constitutes a political order that embeds capital punishment into the centre of its tough regime, deemed beneficial and necessary for a well-ordered, clean and pure society (see Hacking 2003; Lee 2000; Quah 2009; Rajah 2014).

The state’s tough stance is re-emphasised through continual efforts to resist ‘international pressure’ to adopt softer ‘drug-tolerant’ approaches (Shanmugam 2016). Here, the power to continue administrating capital punishment is justified by a sovereign state that emphasises its ‘right’ to act in the interests of its people—Singapore holds itself neither responsible nor accountable to international standards of human rights that frame capital punishment as a ‘cruel, inhumane and degrading punishment’ that ‘undermines human dignity’ (UN, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 5).

Conversely, if international standards and UN membership were held sovereign over state powers, commitment to the death penalty would be deemed a breach of responsibility to social orders established following the Second World War, rather than an ‘exception’ perceived to be incompatible with conceptions of state interests.[19] The absence of sanctions to hold Singapore accountable adds to the reduction of legitimacy of international human rights frameworks. States are not only held unaccountable for their actions, but allowed to freely participate in the global economy while continuing to have effective relationships with countries that have abolished and ceased capital punishment. Against this backdrop, South-East Asian states, like Singapore, appear to prioritise adherence to regional non-governmental bodies, such as ASEAN, rather than the UN in relation to capital punishment and other crime control issues (Luong 2017).

The case of Singapore illustrates the tensions inherent in international human rights standards and diverging national constitutional legal norms. Accordingly, such patterns appear consistent with other Asian states, which ‘pick and choose’ which ‘rights’ discourse to adhere to.[20] South-East Asian states appear to prioritise state sovereign rights to act on behalf of the interests of the ‘larger public’. This dialogic process of disapproving or delegitimising an opposing position and preventing formal denunciations via UN resolutions, is less about trying to apply or revise the law, and more about avoiding political disapproval and the accompanying stigma (Claude Jr 1966). In this case, Singapore’s quest to deflect formal disapproval and avoid accountability is most evident in how severely and consistently it has responded to criticism about its criminal justice practices. Such actions should be viewed in addition to historically discursive thematisation of ‘survival’ by both the leadership and the led (Chua 1995, 19), thus allowing such reiterations in contemporary justifications of capital punishment to occur within a broader tough, regimental and punitive framework.

Conclusion

This article has considered how Singapore justifies its active-retentionist policy and the continued practice of capital punishment in a state-waged war on drugs. National sovereignty, deterrence and ensuring the safety and security of its citizens have been identified as the key rationales invoked to legitimise the continuation of capital punishment in the face of the global abolition movement. These rationales reflect the continuance of ‘national survival’ themes in legal and political dialogues around drug crime and punishment. Singapore’s choice to retain and emphasise state executions in response to drug offences needs to be understood within its tough legal framework. Here, capital punishment acts as a symbolic noose that ties the state’s punitive threads of fines, flogging and hanging together within a responsive, efficient, ‘rightfully’ punitive response that adheres strictly to a state-constructed ‘just’ rule of law. This makes leadership decisions to carry on repressive interventions such as this more palatable to Singapore citizens under the communitarian ideology that has been constructed, promoted and re-emphasised since independence, alongside other political and legally repressive mechanisms to suppress opposition. Capital punishment is now wielded to supress individual rights to life, alongside continual repression of opposing voices and petitions for clemency.[21] The collective interests of a disciplined, clean, drug-free society is maintained through strict application of the law (Misuse of Drugs Act).

The state’s longstanding ‘war on drugs’ has provided an ideal platform for the state to consolidate its choice to retain capital punishment, especially in the face international criticism and the global abolitionist movement. While this article has considered state justification in a rigorous analysis of official discourse, the resisting discourse needs to be considered more closely in relation to ‘top-down’ objectives; especially given that alternative debates have recently started taking root in public discourse. This indicates that human rights discourse needs to be analysed in relation to official state discourse. The rise of several notable local anti-death penalty organisations, such as Community Action Network, Function 8, Maruah, Singapore Anti-Death Penalty Campaign, Think Centre and We Believe in Second Chances indicates that awareness around the administration of death penalty is slowly increasing. Future research conducted by the researchers will compare and contrast human rights and state perspectives.

Acknowledgements

This research was not funded by any organisation or university. It was an independent project conducted by both Ariel and Shih Joo. The authors would like to thank Dr Jarrett Blaustein for his help, advice and time in assisting with developing theoretical discussions of this paper, and reading through several drafts of the article. They also acknowledge the advice and guidance provided by Associate Professor Marie Segrave and Dr Claire Spivakovsky in the publication process. Finally, appreciation and thanks to the two anonymous reviewers and editors of the International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy for strengthening and grounding the discussion within broader sociological frameworks.

Correspondence: Ariel Yap, School of Social Sciences, Monash University, 20 Chancellors Walk, Clayton Campus VIC 3800 Australia. Email: ariel.yap@monash.edu

Abdullah N (2005) Exploring constructions of the ‘drug problem’ in historical and contemporary Singapore. New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies 7(2): 40–70.

Amnesty International (2016) Abolitionist and retentionist countries as of 19 December 2016. https://www.amnesty.org/download/Documents/ACT5038312016ENGLISH.PDF.

Arora V (2016) ‘Apprentice’: Filmmaker explores capital punishment in Singapore. The Diplomat, 15 November. https://thediplomat.com/2016/11/apprentice-filmmaker-explores-capital-punishment-in-singapore/

Association of Southeast Asian Nations (2013) ASEAN Human Rights Declaration and the Phnom Penh Statement on the Adoption of the ASEAN Human Rights Declaration (AHRD) as of February 2013. https://www.asean.org/storage/images/ASEAN_RTK_2014/6_AHRD_Booklet.pdf

Bae S (2008) Is the death penalty an Asian value? Asian Affairs 39(1): 47–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/03068370701791899

Balakrishnan V (2016) Intervention at the High-Level Side Event at UNGA—“Moving Away from the Death Penalty: Victims and the Death Penalty” . Paper presented at the UN General Assembly, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 22 September. https://www.mfa.gov.sg/Newsroom/Press-Statements-Transcripts-and-Photos/2016/09/MFA-Press-Release-Transcript-of-Minister-Vivian-Balakrishnans-Intervention-at-the-HighLevel-Side-Eve

Barr M (2000) Lee Kwan Yew and the “Asian values” debate. Asian Studies Review (24)3: 309–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357820008713278

Beetham J (2013) Revisiting legitimacy, twenty years on. In Tankebe J and Liebling A (eds) Political Science Perspectives on Legitimacy and Criminal Justice: 19–36. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Boo JF (dir) (2016) Apprentice. Singapore: Clover Films.

Central Narcotics Bureau (2002) Singapore Drug Situation Report 2002. Singapore: CNB.

Central Narcotics Bureau (2003) Singapore Central Narcotics Bureau Bulletin. Singapore: CNB.

Central Narcotics Bureau (2016) Heroin and ‘Ice’ Worth More Than $282,000 Seized at Woodlands Checkpoint. News Release, 17 May. https://www.cnb.gov.sg/NewsAndEvents/News/Index/heroin-and-'ice'-worth-more-than-s282-000-seized-at-woodlands-checkpoint

Chan HC (1971) Singapore: The Politics of Survival. Singapore: Oxford University Press.

Chan WC, Tan ES, Lee J and Mathi B (2018) Public opinion on the death penalty in Singapore: Survey Findings. NUS Working Paper 2018/002. February.

Chan WC (2017) The Singapore Story on the Death Penalty (presented at Maruah Forum, The Death Penalty—Yay or Nay, 27 May).

Chan WC (2016) The death penalty in Singapore: In decline but still too soon for optimism. Asian Criminology 11: 179–206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-015-9226-x

Chen S (2015) Discretionary death penalty for convicted drug couriers in Singapore: Reflections on the High Court jurisprudence thus far. IIUM Law Journal 23(1): 31–60.

Chua B (2009) Letter from International Bar Association’s Human Rights Institute (IBAHRI). Response, Ministry of Law, 21 May.

Chua BH (1995) Communitarian Ideology and Democracy in Singapore. London: Routledge.

Chua SC (1977) Singapore. Parliamentary Debates 37(34): 27 May.

Claude IL (1966) Collective legitimization as a political function of the United Nations. International Organization 20(3): 367–379. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-09826-2_11

Cloninger D and Marchesini R (2001) Execution and deterrence: A quasi-controlled group experiment. Applied Economics 33(5): 569–576.

Degenhardt L, Chiu WT, Sampson N, Kessler RC and Anthony JC (2008) Toward a global view of alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, and cocaine use: Findings from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. PLoS Med 5(7): e141. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0050141

Ehrlich I and Liu Z (1999) Sensitivity analyses of the deterrence hypothesis: Let’s keep the econ in econometrics. Journal of Law and Economics 42(1): 455–487. https://doi.org/10.1086/467432

Garland D (1990) Punishment in Modern Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Goh CT (1988) Our national ethic. Speeches 12: 12–15.

Graif C, Gladfelter AS and Matthews SA (2014) Urban poverty and neighbourhood effects on crime: Incorporating spatial and network perspectives. Sociology Compass 8(9): 1140–1155. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12199

Hacking I (2003) Risk and Dirt. In Ericson RV and Doyle A (eds) Risk and Morality. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Harm Reduction International (2016) Regional Overview 21. Asia. Global State of Harm Reduction, November.

Heng LL (2008) A fine city in a garden—environmental law and governance in Singapore. Singapore Journal of Legal Studies July: 68–117.

Heng G and Devan J (1992) State fatherhood: the politics of nationalism, sexuality, and race in Singapore. In Parker A (ed.) Nationalisms and Sexualities: 343-364. Routledge: London, New York.

Holbig H (2011) International dimensions of legitimacy: Reflections on Western theories and the Chinese experience. Journal of Chinese Political Science 16(2): 161–181.

Hood R and Hoyle C (2017) Towards the global elimination of the death penalty: A cruel, inhuman and degrading punishment. In Carlen P and Ayres FL (eds) Alternative Criminologies: 400–422. Thousand Oaks: Taylor and Francis.

Hor M (2004) The death penalty in Singapore and international law. Singapore Year Book of International Law 8: 105–117.

Johnson DT and Zimring FE (2009) The Next Frontier: National Development, Political Change, and the Death Penalty in Asia. New York: Oxford University Press.

Johnson DT (2010) Asia’s declining death penalty. Journal of Asian Studies 69(2) 337–346. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021911810000021

Johnson DT (2013) The jolly hangman, the jailed journalist, and the decline of Singapore’s death penalty. Asian Criminology 8: 41–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-012-9143-1

Karstedt S (2013) Trusting authorities: Legitimacy, trust and collaboration in non-democratic regimes. In Tankebe J and Liebling A (eds) Political Science Perspectives on Legitimacy and Criminal Justice: 127–156. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lai YK (1975) Big rise in number of addicts: Heroin the no.1 menace. The Straits Times, 21 April. https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/Digitised/Article/straitstimes19750421-1.2.104?ST=1&AT=advanced&DF=&DT=24%2F12%2F1979&NPT=&L=&CTA=&k=badminton%26ka%3Dbadminton&P=549

Lee HL (1989) The national identity—A direction and identity for Singapore. Speeches 13: 26–38.

Lee JT (2012) The Past, Present and Future of the Internal Security Act. Maruah: 6-9. https://maruahsg.files.wordpress.com/2012/06/dd_final-1.pdf

Lee KY (1990) Speech by Prime Minister Mr Lee Kuan Yew at the Opening of the Academy of Law on Friday, 31 August 1990. National Archives of Singapore. Accessed 29 January 2018. http://www.nas.gov.sg/archivesonline/data/pdfdoc/lky19900831.pdf.

Lee KY (2000) From Third World to First: The Singapore Story 1965–2000. Singapore: Singapore Press Holdings/Times Singapore.

Lehrfreund S (2013) The impact and importance of international human rights standards: Asia in world perspective. In Hood R and Deva S (eds) Confronting Capital Punishment in Asia: 23–45. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Leong LWT (2008) From ‘Asian values’ to Singapore exceptionalism. In Avonius L and Kingsbury D (eds) Human Rights in Asia: A Reassessment of the Asian Values Debate: 121–140. London: Springer Link.

Lines R (2018) Trump take note—Why Singapore’s claim that the death penalty works for drug offences is fake news. The Conversation, 20 March. http://theconversation.com/trump-take-note-why-singapores-claim-that-the-death-penalty-works-for-drug-offences-is-fake-news-92305

Lye V (2015) Speech delivered by Mr Victor Lye, Chairman of the National Council Against Drug Abuse (NCADA) at the Asian Pacific Forum. Central Narcotics Bureau, 27 August. https://www.cnb.gov.sg/NewsAndEvents/News/Index/speech-by-mr-victor-lye-chairman-of-the-national-council-against-drug-abuse-(ncada)-at-the-asia-pacific-forum-against-drugs-(apfad)-on-27-aug-2015

Matthews R (2005) The myth of punitiveness. Theoretical Criminology 9(2): 175–201. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1362480605051639

Menon (2017) ‘Keynote Address by Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon at ACT! Conference on At-Risk Youths’. Ministry of Social and Family Development. https://www.msf.gov.sg/media-room/Pages/Keynote-Address-by-Chief-Justice-Sundaresh-Menon-at-ACT!-Conference-on-At-Risk-Youths.aspx.

Ministry of Home Affairs (2012) Amendments to the Misuse of Drugs Act. Central Narcotics Bureau. https://www.cnb.gov.sg/NewsAndEvents/News/Index/amendments-to-the-misuse-of-drugs-act.

Ministry of Home Affairs (2018) Judicial Executions: Annual. Singapore Prison Service. https://data.gov.sg/dataset/judicial-executions.

Ministry of Law (2012) Ministry of Law’s response to AFP report, “Singapore eases death penalty policy” 21 November. https://www.mlaw.gov.sg/news/replies/ministry-of-law_s-response-to-afp-report---singapore-eases-death/

Mocan HN and Gittings RK (2003) Getting off death row: Commuted sentences and the deterrent effect of capital punishment. Journal of Law and Economics 46(2): 453–478. https://doi.org/10.1086/382603

Oehlers A and Tarulevicz N (2005) Capital punishment and the culture of developmentalism in Singapore. In Sarat A and Boulanger C (eds) Cultural Lives of Capital Punishment: 291–307. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Permanent Mission of the Republic of Singapore (PMS) (2016) Statement by the Permanent Mission of Singapore during the General Debate on Agenda Item 3 at the 33rd session of the Human Rights Council on 16 September 2016. https://www.mfa.gov.sg/content/mfa/overseasmission/geneva/speeches_and_statements-permanent_mission_to_the_UN/2016/201609/press_20160916.html.

Permanent Mission of the Republic of Singapore (PMS) (2017) Statement by the Permanent Mission of Singapore during Agenda Item 2 of the 36th Session of the Human Rights Council on 12 September 2017. https://www.mfa.gov.sg/content/mfa/overseasmission/geneva/press_statements_speeches/2017/201709/press_201709190.html.

Pratt J and Eriksson A (2013) Contrasts in Punishment: An Explanation of Anglophone Excess and Nordic Exceptionalism. London: Routledge.

Pratt J (2002) Punishment and Civilisation. London: Sage.

Pratt J (2006a) Penal Populism. London: Routledge.

Pratt J (2006b) The dark side of paradise. Explaining New Zealand’s history of high imprisonment. British Journal of Criminology 46(4): 541–560. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azi095

Pratt J (2007) Penal Populism. London: Routledge.

Quah JST (2009) Governance and corruption: Exploring the connection. American Journal of Chinese Studies 16(2): 119–135.

Rajah J (2012) Authoritarian Rule of Law. Legislation, Discourse and Legitimacy in Singapore. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rajah J (2014) Flogging gum: Cultural imaginaries and postcoloniality in Singapore’s rule of law. Law Text Culture 18: 135–165.

Reach (2016) Findings of Poll on Attitudes towards the Death Penalty. https://www.reach.gov.sg/~/media/2016/news-and-press-release/reach-poll-on-attitudes-towards-death-penalty.pdf

Renshaw CS (2012) The ASEAN Human Rights Declaration 2012. Human Rights Law Review 13(3): 557–579. https://doi.org/10.1093/hrlr/ngt016

Reus-Smit C (2014) Power, legitimacy, and order. Chinese Journal of International Politics 7(3): 341–359. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjip/pou035

Sampson RJ (1985) Neighbourhood and crime: The structural determinants of personal victimisation. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 22(1): 7–40. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0022427885022001002

SANA (2018) Innocence lost & found. Singapore Anti-Narcotics Association (blog), 5 March. https://www.sana.org.sg/index.php/2018/03/05/innocence-lost-found/

Shanmugam K (2009) Oral Answer by Law Minister K Shanmugam to Parliamentary Question on Penal Policy. Ministry of Law Singapore. 19 January, https://www.mlaw.gov.sg/news/parliamentary-speeches-and-responses/oral-answer-by-law-minister-k-shanmugam-to-parliamentary-question-on-penal-policy.html.

Shanmugam K (2012a) Ministerial Statement by the Minister of Foreign Affairs and Law, Mr K Shanmugam on the Changes to the application of the mandatory death penalty to homicide offences. Ministry of Law Singapore, 9 July.

Shanmugam K (2012b) Response to NMP Eugene Tan. Ministry of Law Singapore, 9 July.

Shanmugam K (2012c) Response NMP Faizah Jamal. Ministry of Law Singapore, 9 July.

Shanmugam K (2014) Transcript of Statement by Mr K Shanmugam, Minister for Foreign Affairs and Minister of Law of the Republic of Singapore at the 69th session of UN General Assembly; Moving Away from the Death Penalty: National Leadership. Ministry of Foreign Affairs Singapore, 25 September.

Shanmugam K (2016) Chairman’s Statement of the 5th ASEAN Ministerial Meeting on Drug Matters. Central Narcotics Bureau, 20 October.

Shanmugam K (2017a) Speech by Minister K Shanmugam for MHA at COS 2017. Ministry of Information and Communication, 3 March.

Shanmugam K (2017b) Parliamentary Debate on the Motion on Drugs “Strengthening Singapore’s Fight Against Drugs. Ministry of Home Affairs, 5 April, https://www.mha.gov.sg/Newsroom/speeches/Pages/Parliamentary-Debate-on-the-Motion-on-Drugs-Strengthening-Singapores-Fight-Against-Drugs.aspx.

Singapore government (2004) Response to Amnesty International’s Report ‘Singapore—The Death Penalty: A Hidden Toll of Executions’. http://www.nas.gov.sg/archivesonline/speeches/view-html?filename=2004013005.htm.

Singapore Parliament (1991) White Paper on Shared Values, Singapore.

Tan EKB (2000) Laws and values in governance: The Singapore way. Hong Kong Law Journal 30(1): 91–119.

Tan ES (2017) Public Opinion on the Death Penalty: Findings from a Singapore Survey (Paper presented at The Death Penalty: Yea or Nay, Maruah, 27 May).

Tankebe J (2013) Viewing things differently: The dimensions of public perceptions of police legitimacy. American Society of Criminology 51(1): 103–135. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2012.00291.x

Tew Y (2012) ‘Beyond “Asian values”: Rethinking rights’. CGHR Working Paper 5. Cambridge: University of Cambridge Centre of Governance and Human Rights.

Tey TH (2010) Death penalty Singapore-style: Clinical and carefree. Common Law World Review 39: 315–257. https://doi.org/10.1350%2Fclwr.2010.39.4.0208

Thio LA (2004) The death penalty as cruel and inhuman punishment before the Singapore High Court? Customary human rights norms, constitutional formalism and the supremacy of domestic law in public prosecutor v Nguyen Tuong Van (2004). Oxford University Commonwealth Law Journal 4(2): 213–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729342.2004.11421445

Tippet G (2005) The precision of ritual in the gallows’ shadow. The Age, 24 November. https://www.theage.com.au/national/the-precision-of-ritual-in-the-gallows-shadow-20051124-ge1axq.html

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2001) Capital punishment and implementation of the safeguards guaranteeing protection of the rights of those facing the death penalty. Commission on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice, 10th Session, 29 March. https://www.unodc.org/pdf/crime/10_commission/10e.pdf

van Dijk TA (1997) Discourse as interaction in society. In Van Dijk TA (ed.) Discourse as Social Interaction. Newbury Park: Sage.

van Zyl Smit D (2013) Legitimacy and the development of international standards for punishment. In Tankebe J and Liebling A (eds) Political Science Perspectives on Legitimacy and Criminal Justice: 267–292. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wang G (1980) Power, rights and duties in Chinese history. Australian Journal of Chinese Affairs 3: 1–26. https://doi.org/10.2307/2159007

Yeo G (1992) Eastern roots, western winds. The Straits Times, 9 June.

Zimring FE, Fagan J and Johnson DT (2010) Executions, deterrence and homicide: A tale of two cities. Journal of Empirical Legal Studies 7(1): 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-1461.2009.01168.x

Legislation cited

Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (Singapore). 1965.

Internal Security Act (Singapore). 1960 (rev. 1987).

Misuse of Drugs Act (Singapore). 1973 (rev. 2008).

Misuse of Drugs (Amendment) Act (Singapore). 2012.

Penal Code (Singapore). 1871 (rev. 2008).

United Nations Moratorium on the Use of the Death Penalty. UN General Assembly Resolution 62/149. 2007.

United Nations Moratorium on the Use of the Death Penalty. UN General Assembly Resolution 63/168. 2008.

United Nations Moratorium on the Use of the Death Penalty. UN General Assembly Resolution 65/206. 2010.

United Nations Treaty Series, 'Geneva III' Geneva Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War.1949.

United Nations Treaty Series, 'Protocol I' Protocol Additions to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and Relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts. 1977.

Universal Declaration of Human Rights. General Assembly Resolution 217 A. 1948.

Cases cited

Yong Vui Kong v Public Prosecutor Court of Appeal, (2010). SGCA 20 (Sing.)

[2] Indonesia, Malaysia and Vietnam are the other three states to have carried out executions for drug-related offences. Cambodia and Philippines are fully abolitionist. Thailand has an unofficial moratorium in place. Brunei, Laos and Myanmar are abolitionist in practice (see Amnesty International 2017, 16).

[3] Twenty-two of thirty-three executed for drug-related offences from 2007–2017, and six men executed for drug trafficking in October 2018.

[4] See We Believe in Second Chances for profile of executed. See also highly publicised cases of foreign nationals executed for drug offences. For example, cases of: Johannes van Damme, Tong Ching-man, Lam Cheuk-wang, Poon Yuen-chung, Angel Mou Pui-peng, Shanmugam Mrugesu, Van Tuong Nguyen Iwuchukwu Amara Tochi, Prabagan Srivijayan, Billy Agbozo and Prabu Pathmanathan.

[5] Murder and firearms offences constitute the remaining 26.6 and 1.9 per cent respectively.

[6] Referred to as MDA herein after.

[7] Singapore was independent for eight years when the extension of capital punishment was proposed under the MDA in 1973.

[8] Terrorism and the risk of being overwhelmed by ‘other’ non-Asian values or norms are also constructed as serious threats (see Barr 2000; Rajah 2012 for further discussion).

[9] Shanmugam (2016) polarises Singapore/Asian values with Western/international approaches towards drugs by contrasting drug-free and drug-tolerant societies in his speech.

[10] Zimring et al. compared the homicide rates between Singapore and Hong Kong, where capital punishment was abolished in 1993 and found little difference.

[11] The state also canes individuals for graffiti and fines are handed out for spitting, littering and forgetting to flush the toilet.

[12] Rule of law argument by state officials (Balakrishnan 2016; PMS 2017; Shanmugam 2014), see below for discussion of the rule of law

[13] For example, ‘Canadian debates state that crime and murder are products of our society. The death penalty punishes the fact and does nothing to remove the cause or find a cure’ (Hansard [1967–1168] 616, 12 December 1967 in Pratt 2002, 30).

[14] This is one of several human rights infringements the State has been criticised for over the last decade. Other criticisms include the use of arbitrary detention under the the Internal Security Act 1960 (rev. 1985), as well as the curtailment and limitation of press freedoms, and freedoms of speech and expression in everyday life (see Lee 2012, and Song 2017 for detailed discussion on these issues)

[15] Such voices in the case of Singapore would be those of lawyers, activists, advocates and respective human rights watch organisations (United Nations, Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, We Believe in Second Chances and Anti-Death Penalty Asia Network).

[16] This discourse has been increasingly directed towards international human rights organisations (see Singapore government 2004; Ministry of Law 2009, 2012; Shanmmugam 2014; Balakrishnan 2016).

[17] This, however, does not appear to be expressed explicitly. One can also infer that silence could be that of a dull compulsion to adhere to the rule of law, rather than an expressed support for capital punishment.

[18] ‘The death penalty is primarily a criminal justice issue, and therefore is a question for the sovereign jurisdiction of each country’ (Singapore representative to UN in Amnesty International report 2004).

[19] State interests of protecting the public, maintaining safety and security, and controlling the drug ‘epidemic’ evident in official discourse discussed in pp. 7–8.

[20] See ASEAN Human Rights Declaration 2012 and the list of signatories (in ASEAN 2013), the declaration (AHRD) was adopted on 18th November 2012 (see Renshaw 2012 for a more detailed discussion).

[21] Last petition for clemency in Singapore was granted by President Ong Teng Cheong in May 1998. Mathavakannan Kalimuthu’s sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. There have been six grants of clemency since 1965.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/IntJlCrimJustSocDem/2020/21.html