|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy |

Protections for Marginalised Women in University Sexual Violence Policies

Columbia University, United States

|

Abstract

Higher education institutions in four of the top 20 wealthiest nations

globally (measured by GDP per capita) undermine gender equality

by failing to

address sexual violence perpetrated against women with marginalised identities.

By analysing student sexual violence

policies from 80 higher education

institutions in Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States, I

argue that these

policies fail to account for the ways that race, sexuality,

class and disability shape women’s experiences of sexual violence.

Further, these deficiencies counteract efforts to achieve gender equality by

tacitly denying women who experience violence access

to education and health

care. The conclusion proposes policy alterations designed to address the complex

needs of women with marginalised

identities who experience violence, including

implementing cultural competency training and increasing institution-sponsored

health

care services for sexual violence survivors.

Violence against women; higher education; sexual violence;

intersectionality; gender equality

|

Please cite this article as:

Roskin-Frazee A (2020) Protections for marginalised women in university sexual violence policies. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 9(1): 13-30. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.v9i1.1451

![]() This work

is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution

4.0 International Licence. As an open access journal, articles are free to

use with proper attribution. ISSN: 2202-8005

This work

is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution

4.0 International Licence. As an open access journal, articles are free to

use with proper attribution. ISSN: 2202-8005

When Black law school student Brandee Blocker Anderson was sexually assaulted in 2015, she sought help from her prestigious United States university; by the time the school completed its assault investigation, Brandee was quizzed about sexual innuendo in rap music, forced to wait weeks for psychological help, required to seek outside medical care that saddled her with a multi-thousand dollar medical bill, and cautioned not to report her Black perpetrator out of ‘racial solidarity’ (Blocker Anderson 2016a, 2016b). Her experience is a reminder that sexual violence in educational systems continues to deny women—especially women with marginalised identities—equal access to educational opportunities, adequate health care, and economic stability.

The World Health Organization (2013) found that 35 per cent of women globally have experienced sexual violence (a term that encompasses behaviours ranging from harassment to rape) or other forms of intimate partner violence. Other studies have established that 46.4 per cent of lesbian women, 74.9 per cent of bisexual women, and 53 per cent of Black trans people experience sexual violence (Centers for Disease Control 2010; James et al. 2017). The Australian Human Rights Commission (2017) found that a quarter of Australian university students were sexually harassed in a university setting in 2016. The largest national survey on college campus sexual violence in the US from the Association of American Universities (AAU) similarly discovered that 26.4 per cent of undergraduate women were sexually assaulted (Cantor et al. 2019), which mirrored the results from Ms. Magazine’s nationwide survey on rape and attempted rape decades earlier (Warshaw 2019: 11).

Violence against women in educational systems leads to women performing poorly in their academic lives (Jordan et al. 2014), dropping out of school (Mengo and Black 2015), suffering from physical and psychological illnesses (Golding 1999; Stepakoff 1998; van Roosmalen and McDaniel 1999), and going into debt (US Department of Justice 2003; Peterson et al. 2017). Women who experience sexual violence often require health care (Assari and Moghani Lankarani 2018; Chivers-Wilson 2006), but depending on where a woman lives, it can be difficult or illegal to obtain emergency contraceptives, counselling, medications to prevent sexually transmitted infections, abortions, and other treatments that are often needed after a sexual assault (Arnold 2014; Tennessee et al. 2017). Given these ramifications, sexual violence in educational systems denies women access to education, subjects them to financial turmoil, and deprives them of the opportunity to lead healthy lives (Chu 2017; Greco and Dawgert 2007; Kingkade 2016). These effects run contrary to several United Nations sustainable development goals that aim to reduce inequality and poverty (Sengupta 2015) and the United Nations’ Guidance Note on Campus Violence Prevention and Response (2018), which outlines the importance of eliminating violence against women in educational settings.

Considering the significant consequences women can face after experiencing violence in educational settings, examining how schools address violence against women with marginalised identities is crucial. This article presents an international comparative policy analysis of how schools provide or deny women with marginalised identities social protection (systems and policies that reduce inequality) in student sexual violence policies. First, I provide an overview of previous sexual violence scholarship, with a focus on violence against women with marginalised identities. Second, I examine how the failure to implement cultural competency training (a training for professionals on how to deal with diversity), practices of racialised policing, and a general lack of health care access can affect campus violence survivors. Third, I provide data on how student sexual violence policies from 80 higher education institutions in four countries address violence against women with marginalised identities. Finally, I explore areas for future research that could help ensure women with marginalised identities can access educational opportunities, as set out in the UN sustainable development goals of gender equality, quality education, and good health and wellbeing (United Nations 2015). Ultimately, I argue that for higher education institutions to provide social protection to women, school sexual violence policies must address the increased prevalence of violence against women with marginalised identities. Further, these policies should provide survivors of violence with accessible and culturally competent resources and health care.

History of Sexual Violence Scholarship

The legal system in Westernised cultures historically considered rape a property matter, as women were always their father or husband’s property (Brownmiller 1975: 16–30). A more modern legal conception of sexual violence defined it with strict anatomical features (e.g., penile penetration of a vagina); MacKinnon (1987: 82–87) argued that this definition failed to acknowledge several behaviours that could constitute sexual violence or frame sexual violence from the perspective of a woman’s experience of violation. MacKinnon (1987: 85) also emphasised that sexual violence was an ‘abuse of power, not sexuality’, a sentiment affirmed in the use of rape as a weapon of domination in war (Brownmiller 1975: 125).

A crucial development in sexual violence scholarship occurred in the late 1980s and early 1990s when scholars further examined how sexual violence affected those with marginalised identities. Spillers (1987) proposed racism, by altering the construction of language used to describe Black women’s bodies, stripped Black women of their humanity and gender; this ungendering process reduced Black women to flesh and rendered their bodies disposable. Crenshaw (1991: 1243–1244) subsequently used the term intersectionality to describe how marginalised identities interacted with one another to create different realities; Black women, for example, experienced discrimination at the junction of race and gender, which left them vulnerable to racialised sexual violence that separated them from Black men and white women.

Scholarship on sexual violence built on Crenshaw’s theory of intersectionality in the 2000s. McGuire (2011) researched Recy Taylor, a Black woman who was sexually assaulted by several white men in 1944, and how her case was emblematic of rampant sexual violence targeting Black women. Haley (2016: 21), who charted Black women’s experiences in the criminal justice system in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, argued that those in the criminal justice system considered Black women ‘female but altogether distinct and anathema to the construction of normative womanhood’—unworthy of bodily integrity. Armstrong, Gleckman-Krut and Johnson (2018) subsequently argued that focusing exclusively on gender when discussing sexual violence discounted how race and other identities informed sexual violence. Other works such as those from Patterson (2016) and Harris and Linder (2017) centred the voices of those with marginalised identities, with Patterson paying particular attention to how sexual violence affected queer and trans people.

A wave of recent studies demonstrated scholarship on general sexual violence mirrored trends in campus-specific violence. Cantalupo (2018) found evidence suggesting women of colour in the US might be disproportionately likely to experience sexual harassment in educational settings. A study at Columbia University found that queer students experienced higher rates of sexual violence on campus than heterosexual students did (Mellins et al. 2017), and the AAU’s 2015 survey similarly revealed increased rates of sexual victimisation among queer and disabled students (Cantor et al. 2015). The Australian Human Rights Commission Study (2017) uncovered higher rates of sexual harassment that targeted Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, queer, and disabled students.

The Need for Accessible Resources and School Policy Research

Recent sexual violence scholarship indicates that identity influences the specific women who can access institutional support after experiencing violence (Müller 2017; Schulze and Perkins 2017). In countries that criminalise homosexuality, including many countries in Southern Africa, queer women face added barriers when seeking health care because they risk hearing insensitive comments or experiencing incarceration (Müller et al. 2018). Women of colour in the US, who are less likely to report sexual violence due to a long history of experiencing racist police violence (Ritchie 2017; Jacobs 2017), often cannot access the same amount of support from rape crisis centres as white women (Crenshaw 1991: 1251). Low-income survivors, many of whom are people of colour (McKernan et al. 2013), often cannot access health care due to cost, even in countries with universal health care plans—including Australia, Canada, and the UK—that cover many (but not all) health care costs for citizens (Soril et al. 2017).

As the three anecdotal experiences of US survivors described below suggest, current school practices appear to disenfranchise survivors with marginalised identities when schools lack cultural competency training, accessible health care, and reporting mechanisms that are separate from law enforcement.

Brandee’s Story

Brandee was a student at a prestigious law school when she alleged a classmate had sexually assaulted her at a party. Brandee reported her assault to her school and received several responses that illustrate how women of colour can experience discrimination within school sexual violence proceedings.

The head of Sexual Violence Response, the office at Brandee’s school tasked with providing support to survivors of violence in the wake of assaults, encouraged Brandee to reconsider reporting her Black perpetrator out of ‘racial solidarity’ (Blocker Anderson 2016b). Brandee described one meeting in which school investigators quizzed her about rap lyrics, despite neither she nor her assailant mentioning rap music (Blocker Anderson 2016a). According to an opinion piece Brandee published in a campus magazine, investigators revealed to her that her assailant had accused her of inviting him to her apartment for a ‘slurp, slurp, slurp’—a slang phrase for a type of oral sex (Blocker Anderson 2016a). Brandee denied making the comment. The investigators proceeded to ask Brandee if she had ever heard that phrase in rap music lyrics (Blocker Anderson 2016a). The investigators’ mention of rap music—a music style created by Black people in low-income housing projects (Pelton 2007)—connected Brandee’s race to the sexual slang. The link here between sexual promiscuity and Brandee’s race exemplifies how sexual violence processes on college campuses can easily become racialised.

Brandee further claimed that she experienced delays receiving health care. When she attempted to talk to the counselling centre at her school directly after her assault, she said she was forced to wait three weeks for an appointment, and ultimately took her friend’s appointment so she could see a counsellor sooner (Blocker Anderson 2016b). In addition, when Brandee experienced a panic attack in her school-owned apartment, school employees referred her to an outside hospital that saddled her with thousands of dollars in medical bills that she still has not been able to pay back (Blocker Anderson 2016b).

Brandee’s school ultimately found her perpetrator not responsible under their gender-based misconduct policy (Blocker Anderson 2016b). While there are numerous factors that could have led to the school’s finding in Brandee’s case, the potential relationship between the school’s racialised analysis of Brandee’s character and their investigative findings in favour of her assailant cannot be dismissed.

Erica’s Story

In May 2016, an anonymous Twitter account with the handle @RapedAtSpelman stated the user, whom this article will refer to as ‘Erica’, was raped at Spelman College, an all-women’s historically Black college (HBCU) in the US. Erica wrote that the college failed to support her after she reported being sexually assaulted by students at sibling HBCU Morehouse College.

According to Erica, after she reported her freshman year rape, a dean ‘said that Spelman & Morehouse are bother & sister so I should give them a pass’ (RapedAtSpelman 2016). The insinuation that Erica should give another HBCU ‘a pass’ because of assumed solidarity between the schools played into historical fears that women of colour have had reporting violence within their communities (Smith 2001). Erica explained that hearing the dean’s comment made her feel worthless. She began to self-harm and planned to leave Spelman at the end of the year (Kingkade 2016).

Norma’s Story

Norma—a college-educated, queer-identified person with disabilities—wrote about her experience being sexually assaulted during her college years, with the hashtag #WhyWeDontReport on Twitter. The hashtag appeared in September 2018 during the US Supreme Court confirmation hearings for accused assailant, Brett Kavanaugh (Lauriello 2019), to draw attention to certain reasons why many survivors of sexual violence do not report assaults. Norma wrote:

I was sexually assaulted by my girlfriend at age 19. Everyone knew the cops didn’t take straight women seriously when they got raped, and they’d never listen to a lesbian assaulted by another woman. They didn’t care about bashing, either. Queers don’t call cops. (Krautmeyer 2018)

Norma’s Tweet highlights the fractured relationship between many in the queer community and law enforcement. Norma’s hesitancy to report her assault due to her distrust of law enforcement reiterates the importance of school policies assuring students that their support services and disciplinary procedures are separate from the criminal justice system.

Given the experiences of Brandee, Erica, and Norma, addressing violence against women with marginalised identities is crucial for providing social protection to all women in educational settings. However, although previous scholars have analysed the linguistic differences in country-specific school sexual violence policies and compared the laws that govern school responses to sexual violence (Graham et al. 2017; Lopes-Baker and McDonald 2017), scholars have not previously conducted an international comparative analysis on how school policies address sexual violence against women with marginalised identities. The lack of international comparative policy analysis is concerning because sexual violence policies, which govern an institution’s response to violence on campus, are critical in informing school practices and addressing experiences such as those of Brandee, Erica, and Norma.

I analysed student sexual violence policies from 80 higher education institutions in four countries: Australia, Canada, the UK, and the US. I selected schools popularly regarded as educational leaders because policies at highly regarded institutions may both influence and reflect public opinion about appropriate responses to sexual violence. To identify these schools, I used the 2020 QS World University Rankings, an international ranking system for higher education institutions (Quacquarelli Symonds 2019). Although QS’s ranking system is a flawed measure of school quality whose methodology disadvantages high-calibre small liberal arts colleges (Leiter 2017), QS’s method of conducting surveys to gauge a school’s public reputation, which accounts for 40 per cent of each school’s ranking (Quacquarelli Symonds 2017), functions as an informal measure of the perception of school quality.

Given this study’s focus on analysing the potential implications of policy deficiencies and proposing areas for future research, I drew from the first 20 schools ranked for each country selected in the 2020 QS World University Rankings. The resulting list of institutions excluded two French Canadian universities (to ensure that language translation would not play a role in linguistic differences in school policies) and consolidated the University of California campuses (given their unified sexual violence policies and procedures).

For the purposes of this study, a student sexual violence policy was a school’s official rules outlining the behaviours that constituted student sexual violence for campus disciplinary proceedings. Broader student conduct policies that listed sexual violence as an example of prohibited conduct stood in for sexual violence–specific policies in institutions that lacked separate sexual violence policies. Some schools separated sexual violence policies from procedures for handling reported cases of sexual violence; for those schools, I analysed both the official policy and procedure documents. To ensure that the study’s focus remained on student experiences, the documents I examined excluded faculty and staff–specific policies and procedures. I also excluded informal school webpages that listed resources for students and other information outside the scope of each school’s formal policy documents.

The four specific policy features that I evaluated were:

1. Marginalised identities: did the policy acknowledge the school recognised that sexual violence disproportionately targets students with marginalised identities?

2. Cultural competency: did the policy indicate that any staff involved in responding to sexual violence on campus were trained in cultural competency?

3. Separation from policing: did the policy explicitly affirm that sexual violence disciplinary processes and support services were separate from law enforcement and/or emphasise that the school enabled survivors to choose whether or not to file police reports (excluding cases involving minors or other mandated reporting situations outside the school’s control)?

4. Health care: did the policy acknowledge an institutional responsibility to provide survivors with ongoing physical or psychological health care? (Note that this did not include 1) stating the school would provide outside referrals; 2) providing contact information for health services at the school without further comment; 3) offering short-term health care services; or 4) offering to transport survivors to or from medical treatment at nearby hospitals.)

While the first question helped illuminate schools that understood intersectionality, the latter three questions addressed specific policy features that could provide direct protection for women with marginalised identities. Several studies found that cultural competency training increased the efficacy of assistance provided to those with marginalised identities (Herring et al. 2013; Qureshi et al. 2008); this made it an important feature of a school’s response to sexual violence. Maintaining separation between law enforcement and a school’s response to sexual violence allowed students with marginalised identities to seek support without risking police violence (Ritchie 2017; Mogul et al. 2012; Sharp and Atherton 2007; Wolitzsky-Taylor 2011). Health care access offered those with marginalised identities the treatment necessary to continue through school without encountering a cost barrier, which could still be a factor in the three countries analysed with universal health care (Soril et al. 2017).

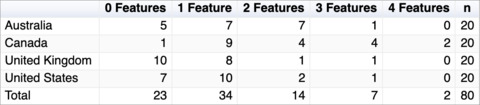

Of the 80 school policies analysed, 71.25 per cent included one or fewer of the policy features evaluated, and 28.75 per cent failed to address any features evaluated. Only two institutions—Dalhousie University and McGill University in Canada—addressed all four policy features evaluated (see Table 1).

Table 1: Number of policy features addressed

Canada was the only country for whom 50 per cent of analysed school policies included two or more of the evaluated features. In contrast, 50 per cent of school policies analysed in the UK and 35 per cent of policies analysed in the US failed to include any feature. Of the 20 school policies analysed in Australia, 60 per cent addressed one or zero features and 40 per cent addressed two or more features.

Table 2: Specific features addressed

In total, 18.75 per cent of the 80 school policies analysed acknowledged that sexual violence disproportionately affects those with marginalised identities. Most of the school policies analysed that addressed marginalised identities (73.33 per cent, or 11 out of 15) were in Canada. For example, the preamble to McGill’s sexual violence policy stated:

[The University] further acknowledges that ... Sexual Violence and its consequences may disproportionately affect members of social groups who experience intersecting forms of systemic discrimination or barriers (on grounds, for example, of gender, sexual orientation, gender identity and expression, race, religion, Indigenous identity, ethnicity, disability or class). (See Appendix A)

In contrast, none of the 20 school policies analysed in the US and only one policy analysed in the UK acknowledged that sexual violence disproportionately targets those with marginalised identities.

Of the policy features evaluated, the one most commonly absent in the 80 school policies analysed was a commitment to cultural competency training. Only 8.75 per cent of school policies analysed included any mention of having staff involved in their sexual violence response processes trained in cultural competency. The one school policy in the US that mentioned cultural competency training, Northwestern University, briefly confirmed that:

[Northwestern University] is committed to making our services accessible to all members of the Northwestern community. The Office is cognizant of the physical accessibility of our space, the cultural competency of our staff, and the method and tone of the services we provide. (See Appendix A)

Northwestern’s policy also stated that the school would offer translation services to students who required language assistance during sexual violence proceedings—an accommodation that was absent in all other school policies analysed.

Separation from policing was the feature evaluated that was most prevalent in school policies analysed. Overall, 60 per cent of the 80 school policies explicitly stated that the school’s disciplinary proceedings and support services were separate from law enforcement. McMaster University in Canada even acknowledged that those with marginalised identities might have issues with law enforcement, emphasising that:

Survivors of Sexual Violence may have different degrees of confidence in institutional services and remedies ... because of their associations of such institutions with sexism, colonialism, racism, and other forms of systemic oppression. (See Appendix A)

McMaster’s policy further used the experiences of women of colour as an example of why some students might not trust law enforcement, arguing that women of colour (including Indigenous women):

May be reluctant to disclose Sexual Violence to institutional authorities due to concerns that racism may impact whether an institution will take their disclosure or complaint seriously, or that their disclosure or complaint may reinforce racist beliefs about men from their communities. (See Appendix A)

McMaster’s final statement echoes scholars such as Smith (2001), whose work argued that a legacy of racism sometimes forced women of colour to remain silent about sexual violence within their own communities for fear of stoking division and racial tensions.

The final policy feature evaluated was a clear institutional commitment to providing survivors of violence with health care services. Of the 80 school policies analysed, 26.25 per cent promised the school would provide longer term, accessible health care to survivors. Most school policies that did not include a commitment to providing survivors with longer term health care did list contact information for school counselling resources or referenced providing survivors with outside referrals or transportation to local hospitals.

Discussion

The lack of cultural competency training among the 80 school policies analysed is particularly pressing to examine further. Brandee and Erica’s stories, which both included school administrators failing to account for a long history of women of colour feeling conflicted about reporting other people of colour for abuse (Smith 2001), indicate the lack of cultural competency training in current school policies can negatively affect women with marginalised identities.

While this study’s small sample size prohibits drawing broad conclusions about policies in any individual country included, the limited results also raise several questions for future research. Canada accounted for 11 out of 15 school policies analysed that acknowledged that those with marginalised identities disproportionately experienced sexual violence. In contrast, 50 per cent of the school policies analysed in the UK lacked all features evaluated, and many even lacked sexual violence policies separate from general student conduct policies. Are these country-wide trends and, if so, what factors influence these policy characteristics? Cultural competency commitments were the most absent of all the features evaluated at the 80 schools. Is this a larger characteristic shared broadly among school policies throughout the world? If so, why are schools averse to or unaware of cultural competency training? What specific cultural competency training methods are schools using when they do agree to integrate cultural competency into their staff training?

Additionally, future research is necessary to establish how policy features influence survivors with marginalised identities. Brandee, Erica, and Norma’s narratives provide three pieces of anecdotal evidence about the potential danger of schools lacking cultural competency training and health care or coordinating with law enforcement; however, more research is required to understand if their experiences are isolated or indicative of larger trends among the experiences of women of colour and queer women in higher education.

Conclusion

Despite sexual violence in educational institutions disproportionately targeting students with marginalised identities, the data I collected from 80 higher education institutions in Australia, Canada, the UK, and the US indicate that those institutions’ sexual violence policies often fail to include policy features that increase social protection for women with marginalised identities. The inconsistencies discovered in the 80 school policies analysed raise questions regarding potential international sexual violence policy failures. Further, anecdotal experiences from three sexual violence survivors at US institutions suggest how gaps in institutional policies could affect women with marginalised identities on campuses.

To advance the UN sustainable development goals and the 63rd annual UN Commission on the Status of Women’s goal of increasing social protection for women and girls (UN Women 2019), higher education institutions should craft sexual violence policies that acknowledge marginalised identities, include cultural competency training for staff, reduce forced survivor interactions with the police, and guarantee survivors have access to affordable health care. Additionally, anti–sexual violence activists on college campuses and scholars studying campus sexual violence should incorporate the needs and experiences of women with marginalised identities into their demands and scholarship. Of course, pushing to amend school policies to reflect the needs of women with marginalised identities is only one component of providing social protection to women, but the immense influence policies have on school practices makes changing sexual violence policies a critical feature of addressing—and ultimately eradicating—school sexual violence.

Correspondence: Amelia Roskin-Frazee, Student, Department of Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, Columbia University, 70 Morningside Drive Box 1564, New York, NY 10027, United States. Email: a.roskin-frazee@columbia.edu

Armstrong E, Gleckman-Krut M and Johnson L (2018) Silence, power, and inequality: An intersectional approach to sexual violence. Annual Review of Sociology 44(1): 99–122. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-073117-041410

Arnold B (2014) Reproductive rights denied: The Hyde Amendment and access to abortion for Native American women using Indian health service facilities. American Journal of Public Health 104(10): 1892–1893. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302084

Assari S and Moghani Lankarani M (2018) Violence exposure and mental health of college students in the United States. Behavioral Sciences (Basel) 8(6): 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs8060053

Australian Human Rights Commission (2017) Change the Course: National Report on Sexual Assault and Sexual Harassment at Australian Universities. Available at https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/document/publication/AHRC_2017_ChangeTheCourse_UniversityReport.pdf (accessed 5 June 2019).

Blocker Anderson B (2016a) Why Students Need the #RightToRecord: One Survivor’s Story. Available at https://reclaimmagazine.wordpress.com/2016/10/28/why-students-need-the-righttorecord-one-survivors-story/ (accessed 28 May 2019).

Blocker Anderson B (2016b) Columbia found my perpetrator not-responsible. 28 October, Columbia University Low Library Plaza, New York.

Brownmiller S (1975) Against Our Will: Men, Women, and Rape. New York: Fawcett Books.

Cantalupo N (2018) And Even More of Us Are Brave: Intersectionality & Sexual Harassment of Women Students of Color. Harvard Journal of Law and Gender 42(1): 1–81.

Cantor D, Fisher B, Chibnall S, Harps S, Townsend R, Thomas G, Lee H, Kranz V, Herbison R and Madden K (2019) Report on the AAU Campus Climate Survey on Sexual Assault and Misconduct. Available at https://www.aau.edu/sites/default/files/AAU-Files/Key-Issues/Campus-Safety/FULL_2019_Campus_Climate_Survey.pdf (accessed 20 November 2019).

Cantor D, Fisher B, Chibnall S, Townsend R, Lee H, Bruce C and Thomas G (2015) Report on the AAU Campus Climate Survey on Sexual Assault and Sexual Misconduct. Available at https://www.aau.edu/sites/default/files/%40%20Files/Climate%20Survey/AAU_Campus_Climate_Survey_12_14_15.pdf (accessed 15 May 2019).

Centers for Disease Control (2010) The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2010 Findings on Victimization by Sexual Orientation. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/pdf/NISVS_SOfindings.pdf (accessed 15 July 2019).

Chivers-Wilson KA (2006) Sexual assault and posttraumatic stress disorder: A review of the biological, psychological and sociological factors and treatments. McGill Journal of Medicine 9(2): 111–118.

Chu A (2017) I Dropped Out of College Because I Couldn’t Bear to See My Rapist on Campus. Available at https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/qvjzpd/i-dropped-out-of-college-because-i-couldnt-bear-to-see-my-rapist-on-campus (accessed 5 June 2019).

Crenshaw K (1991) Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review 43(6): 1241–1299.

Golding J (1999) Intimate partner violence as a risk factor for mental disorders: A meta-analysis. Journal of Family Violence 14(2): 99–132. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022079418229

Graham L, Sarah Treves-Kagan, Erin P. Magee, Stephanie M. DeLong, Olivia S. Ashley, Rebecca J. Macy, Sandra L. Martin, Kathryn E. Moracco, and J. Michael Bowling (2017) Sexual assault policies and consent definitions: A nationally representative investigation of U.S. Colleges and Universities. Journal of School Violence 16(3): 243–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2017.1318572

Greco D and Dawgert S (2007) Poverty and Sexual Violence: Building Prevention and Intervention Responses. Available at https://www.pcar.org/sites/default/files/pages-pdf/poverty_and_sexual_violence.pdf (accessed 16 May 2019).

Haley S (2016) No Mercy Here: Gender, Punishment, and the Making of Jim Crow Modernity. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press.

Harris J and Linder C (2017) Intersections of Identity and Sexual Violence on Campus: Centering Minoritized Students’ Experiences. Sterling: Stylus Publishing.

Herring S, Spangaro J, Lauw M and McNamara L (2013) The intersection of trauma, racism, and cultural competence in effective work with Aboriginal people: Waiting for trust. Australian Social Work 66(1): 104–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2012.697566

Jacobs M (2017) The violent state: Black women’s invisible struggle against police violence. William & Mary Journal of Race, Gender, and Social Justice 24(1): 39–100.

James SE, Brown C and Wilson I (2017) 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey: Report on the Experiences of Black Respondents. Available at http://www.transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/usts/USTSBlackRespondentsReport-1017.pdf (accessed 10 July 2019).

Jordan CE, Combs JL and Smith GT (2014) An exploration of sexual victimization and academic performance among college women. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 15(3): 191–200. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838014520637

Kingkade T (2016) Spelman Rape Victim Says School President Failed on Promise to Meet with Her. Available at https://www.huffpost.com/entry/spelman-president-campus-rape_n_57996063e4b02d5d5ed453f0 (accessed 11 July 2019).

Krautmeyer N (2018) 21 September. Available at https://twitter.com/blushandmumble/status/1043182794506158080 (accessed 15 July 2019).

Lauriello S (2019) #WhyIDidntReport: Alyssa Milano and 9 Other Survivors Share Their Stories. Available at https://www.health.com/mind-and-body/why-i-didnt-report-hashtag-trending (accessed 10 July 2019).

Leiter B (2017) Academic Ethics: To Rank or Not to Rank? Available at https://www.chronicle.com/article/Academic-Ethics-To-Rank-or/240619 (accessed 29 April 2019).

Lopez-Baker A and McDonald M (2017) Canada and United States: Campus sexual assault law & policy comparative analysis. Canada–United States Law Journal 41(1): 156–166.

MacKinnon C (1987) Feminism Unmodified: Discourses on Life and Law. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

McGuire D (2011) At the Dark End of the Street: Black Women, Rape, and Resistance. New York: Vintage Books.

McKernan SM, Ratcliffe C, Steuerle E and Zhang S (2013) Less Than Equal: Racial Disparities in Wealth Accumulation. Available at https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/71362312.pdf (accessed 5 July 2019).

Mellins CA, Walsh K, Sarvet AL, Wall M, Gilbert L, Santelli JS, Thompson M et al. (2017) Sexual assault incidents among college undergraduates: Prevalence and factors associated with risk. PLoS ONE 12(11): e0186471. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0186471

Mengo C and Black BM (2015) Violence victimization on a college campus: Impact on GPA and school dropout. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice 18(2): 234–248. https://doi.org/10.1177/1521025115584750

Mogul J, Ritchie A and Whitlock K (2012) Queer (In)Justice: The Criminalization of LGBT People in the United States. Boston: Beacon Press.

Müller A (2017) Scrambling for access: Availability, accessibility, acceptability and quality of healthcare for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people in South Africa. BMC International Health and Human Rights 17(16). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-017-0124-4

Müller A, Spencer S, Meer T and Daskilewicz K (2018) The no-go zone: A qualitative study of access to sexual and reproductive health services for sexual and gender minority adolescents in Southern Africa. Reproductive Health 15(12). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-018-0462-2

Patterson J (2016) Queering Sexual Violence—Radical Voices from within the Anti-Violence Movement. Riverdale: Riverdale Avenue Books.

Pelton TM (2007) Rap/Hip Hop. Available at https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/rap-hip-hop/ (accessed 10 July 2019).

Peterson C, DeGue S, Florence C and Lokey CN (2017) Lifetime economic burden of rape among U.S. adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 52(6): 691–701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2016.11.014

Quacquarelli Symonds (2017) Methodology. Available at https://www.topuniversities.com/qs-world-university-rankings/methodology (accessed 29 April 2019).

Quacquarelli Symonds (2019) QS World University Rankings 2020. Available at https://www.topuniversities.com/university-rankings/world-university-rankings/2020 (accessed 1 May 2019).

Qureshi A, Collazos F, Ramos M and Casas M (2008) Cultural competency training in psychiatry. European Psychiatry 23(1): 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-9338(08)70062-2

RapedAtSpelman (2016) May 2. Available at https://twitter.com/RapedAtSpelman/status/727260878236717062 (accessed 11 July 2019).

Ritchie A (2017) Invisible No More: Police Violence against Black Women and Women of Color. Holland: Dreamscape Media.

Schulze C and Perkins W (2017) Awareness of sexual violence services among LGBQ-identified college students. Journal of School Violence 16(2): 148–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2017.1284481

Sengupta S (2015) U.N. Adopts Ambitious Global Goals after Years of Negotiations. Available at https://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/26/world/africa/un-adopts-ambitious-global-goals-after-years-of-negotiations.html (accessed 10 February 2019).

Sharp D and Atherton S (2007) To serve and protect? The experiences of policing in the community of young people from black and other ethnic minority groups. The British Journal of Criminology 47(5): 746–763. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azm024

Smith A (2001) The color of violence: Violence against women of color. Meridians 1(2): 65–72.

Soril L, Adams T, Phipps-Taylor M, Winblad U and Clement F (2017) Is Canadian healthcare affordable? A comparative analysis of the Canadian healthcare system from 2004 to 2014. Healthcare Policy 13(1): 43–58. https://doi.org/10.12927/hcpol.2017.25192

Spillers H (1987) Mama’s baby, papa’s maybe: An American grammar book. Diacritics 17(2): 64–81. https://doi.org/10.2307/464747

Stepakoff S (1998) Effects of sexual victimization on suicidal ideation and behavior in U.S. college women. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 28(1): 107–126. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1943-278X.1998.tb00630.x

Tennessee A, Bradham T, White B and Simpson K (2017) The monetary cost of sexual assault to privately insured US women in 2013. American Journal of Public Health 107(6): 983–988. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2017.303742

United Nations (2015) Sustainable Development Goals. Available at https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdgs (accessed 15 January 2019).

United Nations (2018) Guidance Note on Campus Violence Prevention and Response. Available at https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2019/02/guidance-note-on-campus-violence-prevention-and-response (accessed 14 October 2019).

UN Women (2019) CSW63. Available at http://www.unwomen.org/en/csw/csw63-2019 (accessed 15 January 2019).

United States Department of Justice (2003) Criminal Victimization in the United States, 2002 Statistical Tables. Available at https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cvus02.pdf (accessed 10 June 2019).

United States Department of Justice (2013) Female Victims of Sexual Violence, 1994–2010. Available at https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/fvsv9410.pdf (accessed 10 June 2019).

van Roosmalen E and McDaniel S (1999) Sexual harassment in academia: A hazard to women’s health. Women & Health 28(2): 33–54. https://doi.org/10.1300/J013v28n02_03

Warshaw R (2019) I Never Called It Rape (reprint). New York: Harper Perennial.

Wolitzsky-Taylor K, Resnick H, Amstadter A, McCauley J, Ruggiero K and Kilpatrick D (2011) Reporting rape in a national sample of college women. Journal of American College Health 59(7): 582–587. https://doi/org/10.1080/07448481.2010.515634

World Health Organization (2013) Violence against Women. Available at https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women (accessed 15 July 2019).

Appendix A

Australia

The University of Adelaide (2018) Student Misconduct Policy. Available at https://www.adelaide.edu.au/policies/4304/?dsn=policy.document;field=data;id=8105;m=view (accessed 14 June 2019).

The Australian National University (2018) Discipline Rule 2018. Available at https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/F2018L00319/Html/Text#_Toc508885909 (accessed 14 June 2019).

Curtin University (2019) Curtin University Code of Conduct. Available at http://complaints.curtin.edu.au/local/docs/Code_of_Conduct.pdf (accessed 16 June 2019).

Deakin University (2017) Sexual Assault Prevention and Response Policy. Available at https://policy.deakin.edu.au/download.php?id=225&version=1 (accessed 14 June 2019).

Deakin University (2017) Regulation 4.1(1)—General Misconduct. Available at https://www.deakin.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/1122281/regulation_4_1_1_general_misconduct.pdf (accessed 14 June 2019).

Griffith University (2018) Student Sexual Assault, Harassment, Bullying & Discrimination Policy. Available at https://policies.griffith.edu.au/pdf/Student%20Sexual%20Assault%20Harassment%20Bullying%20and%20Discrimination%20Policy.pdf (accessed 16 June 2019).

James Cook University (2018) Bullying, Discrimination, Harassment, and Sexual Misconduct Policy. Available at https://www.jcu.edu.au/policy/student-services/bullying-discrimination-harassment-and-sexual-misconduct-policy-and-procedure (accessed 14 June 2019).

Macquarie University (2019) Student Sexual Assault and Sexual Harassment. Available at https://staff.mq.edu.au/work/strategy-planning-and-governance/university-policies-and-procedures/policies/student-sexual-assault-and-sexual-harassment (accessed 13 June 2019).

The University of Melbourne (2019) Sexual Misconduct Policy and Procedure. Available at https://www.ormond.unimelb.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Sexual-Misconduct-Policy-and-Procedure.pdf (accessed 15 June 2019).

Monash University (2019) Sexual Harassment. Available at https://staff.mq.edu.au/work/strategy-planning-and-governance/university-policies-and-procedures/policies/student-sexual-assault-and-sexual-harassment (accessed 13 June 2019).

Monash University (2018) Guidelines for the University’s Response to Allegations of a Sexual Offense. Available at https://www.monash.edu/__data/assets/pdf_file/0012/1398729/guidelines-sexual-assault.pdf (accessed 13 June 2019).

University of New South Wales (2018) Sexual Misconduct Prevention and Response Policy. Available at https://www.gs.unsw.edu.au/policy/documents/sexualmisconductpreventionandresponsepolicy.pdf (accessed 14 June 2019).

The University of Newcastle (2019) Sexual Assault, Harassment and Crisis Support. Available at https://www.newcastle.edu.au/current-students/support/personal/sexual-assault-harrassment (accessed 14 June 2019).

The University of Queensland (2017) 1.50.13 Sexual Misconduct. Available at http://ppl.app.uq.edu.au/content/1.50.13-sexual-misconduct (accessed 15 June 2019).

Queensland University of Technology (2018) A/8.5 Grievance Resolution Procedures for Discrimination Related Grievances. Available at http://www.mopp.qut.edu.au/A/A_08_05.jsp (accessed 14 June 2019).

RMIT University (2017) Sexual Harassment Policy. Available at https://www.rmit.edu.au/about/governance-and-management/policies/sexual-harassment-policy (accessed 13 June 2019).

University of South Australia (2014) Sexual Assault and Sexual Harassment Policy and Procedures. Available at https://i.unisa.edu.au/contentassets/a6b4fdbe8e6545c59ad88ef910ddd9dc/sexual-assault-and-sexual-harassment-policy.pdf (accessed 15 June 2019).

The University of Sydney (2019) Student Sexual Assault and Sexual Harassment Policy 2018. Available at http://sydney.edu.au/policies/showdoc.aspx?recnum=PDOC2018/470&RendNum=0 (accessed 15 June 2019).

University of Tasmania (2019) University Behaviour Policy. Available at https://www.utas.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/1181985/University-Behaviour-Policy.pdf (accessed 17 June 2019).

University of Technology Sydney (2018) Sexual Assault and Harassment Reporting Privacy Notice. Available at https://www.uts.edu.au/sites/default/files/2018-08/ssu-privacy-notice-sexual-offence-and-sexual-harassment-reporting.pdf (accessed 17 June 2019).

University of Technology Sydney (2017) What Is Sexual Assault? Available at https://www.uts.edu.au/current-students/support/when-things-go-wrong/sexual-assault-indecent-assault-sexual-harassment-1 (accessed 17 June 2019).

The University of Western Australia (2019) University Policy on: Sexual Misconduct. Available at http://www.hr.uwa.edu.au/policies/policies/conduct/sexual-harassment (accessed 12 June 2019).

University of Wollongong (2017) Sexual Harassment Prevention Policy. Available at https://documents.uow.edu.au/about/policy/uow058719.html (accessed 18 June 2019).

Canada

University of Alberta (2017) Sexual Violence Policy. Available at https://policiesonline.ualberta.ca/PoliciesProcedures/Policies/Sexual-Violence-Policy.pdf (accessed 25 June 2019).

The University of British Columbia Board of Governors (2016) Sexual Assault. Available at https://universitycounsel.ubc.ca/files/2016/06/Proposed-Policy-131.pdf (accessed 24 June 2019).

University of Calgary (2017) Sexual Violence Policy. Available at https://www.ucalgary.ca/policies/files/policies/sexual-violence-policy.pdf (accessed 30 June 2019).

Carleton University (2019) Sexual Violence Policy. Available at https://carleton.ca/secretariat/wp-content/uploads/Sexual-Violence-Policy.pdf (accessed 25 June 2019).

Concordia University (2018) Policy Regarding Sexual Violence. Available at https://www.concordia.ca/content/dam/common/docs/policies/official-policies/PRVPA-3.pdf (accessed 25 June 2019).

Dalhousie University (2019) Sexualized Violence Policy. Available at https://www.dal.ca/dept/university_secretariat/policies/human-rights---equity/sexualized-violence-policy.html (accessed 3 July 2019).

University of Guelph (2018) Policy 6.4—Sexual Violence Policy. Available at https://www.uoguelph.ca/secretariat/policy/6.4 (accessed 3 July 2019).

University of Guelph (2018) Procedures for Policy 6.4—Sexual Violence: Procedures for Students. Available at https://www.uoguelph.ca/secretariat/policy/procedure/6.4 (accessed 3 July 2019).

University of Manitoba (2019) University of Manitoba Policy: Sexual Assault. Available at https://umanitoba.ca/admin/governance/media/Sexual_Assault_Policy_-_2016_09_01.pdf (accessed 25 June 2019).

McGill University (2019) Policy against Sexual Violence. Available at https://www.mcgill.ca/secretariat/files/secretariat/policy_against_sexual_violence.pdf (accessed 27 June 2019).

McMaster University (2017) Sexual Violence Policy. Available at https://www.mcmaster.ca/vpacademic/Sexual_Violence_Docs/Sexual_Violence_Policy_effec-Jan_1,2017.pdf (accessed 24 June 2019).

University of Ottawa (2016) Policy 67b—Prevention of Sexual Violence. Available at https://www.uottawa.ca/administration-and-governance/policy-67b-prevention-sexual-violence (accessed 30 June 2019).

Queen’s University (2019) Policy on Sexual Violence Involving Queen’s University Students. Available at https://www.queensu.ca/secretariat/policies/board-policies/sexual-violence-involving-queen%E2%80%99s-university-students-policy (accessed 1 July 2019).

University of Saskatchewan (2015) Sexual Assault Prevention. Available at https://policies.usask.ca/policies/health-safety-and-environment/Sexual%20Assault%20Prevention%20.php#Scopeofthispolicy (accessed 26 June 2019).

University of Saskatchewan (2015) Sexual Assault Prevention Policy Procedures Document. Available at https://policies.usask.ca/policies/health-safety-and-environment/Sexual%20Assault%20Prevention%20.php#Scopeofthispolicy (accessed 26 June 2019).

Simon Fraser University (2017) Sexual Violence and Misconduct Prevention, Education and Support (GP 44). Available at https://www.sfu.ca/policies/gazette/general/gp44.html (accessed 1 July 2019).

University of Toronto (2017) Policy on Sexual Violence and Sexual Harassment. Available at http://www.governingcouncil.lamp4.utoronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/p1215-poshsv-2016-2017pol.pdf (accessed 29 June 2019).

University of Toronto (2002) Code of Student Conduct. Available at http://www.governingcouncil.lamp4.utoronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/p1215-poshsv-2016-2017pol.pdf (accessed 29 June 2019).

University of Victoria (2017) Sexualized Violence Prevention and Response Policy. Available at https://www.uvic.ca/universitysecretary/assets/docs/policies/GV0245.pdf (accessed 1 July 2019).

University of Waterloo Secretariat (2019) Policy 42—Prevention of and Response to Sexual Violence. Available at https://uwaterloo.ca/secretariat/policies-procedures-guidelines/policies/policy-42-prevention-and-response-sexual-violence (accessed 1 July 2019).

University of Western Ontario (2017) Policy 1.52—Policy on Sexual Violence. Available at https://www.uwo.ca/univsec/pdf/policies_procedures/section1/mapp152.pdf (accessed 1 July 2019).

University of Windsor (2016) University of Windsor Policy on Sexual Misconduct. Available at https://www.uwo.ca/univsec/pdf/policies_procedures/section1/mapp152.pdf (accessed 30 June 2019).

York University (2016) Sexual Violence, Policy on. Available at https://secretariat-policies.info.yorku.ca/policies/sexual-violence-policy-on/ (accessed 25 June 2019).

United Kingdom

University of Birmingham (2018) Regulations of the University of Birmingham Section 8—Student Conduct. Available at https://intranet.birmingham.ac.uk/as/registry/legislation/documents/public/Cohort-Legislation-2018-19/Regulations-18-19-Section-8.pdf (accessed 7 June 2019).

University of Birmingham (2018) Guidance for Students Making a Complaint About Another Student(s). Available at https://intranet.birmingham.ac.uk/as/registry/policy/documents/public/student-complaints/Guidance-for-Complainant-Students-V7-FINAL-2018-19.pdf (accessed 7 June 2019).

University of Bristol (2018) Acceptable Behaviour Policy and Information for Students. Available at https://www.bristol.ac.uk/media-library/sites/secretary/documents/student-rules-and-regs/acceptable-behaviour-policy.pdf (accessed 5 June 2019).

University of Bristol (2018) Student Complaints Procedure 2018/19. Available at http://www.bristol.ac.uk/media-library/sites/secretary/documents/student-rules-and-regs/student-complaints-procedure.pdf (accessed 5 June 2019).

University of Cambridge (2018) Procedure on Student Harassment and Sexual Misconduct. Available at https://www.studentcomplaints.admin.cam.ac.uk/files/procedure_on_student_harasshara_and_sexual_misconduct_with_explanatory_notes_-_2019.pdf (accessed 6 June 2019).

University of Cambridge (2019) Code of Conduct for Students in Respect of Harassment and Sexual Misconduct. Available at https://www.studentcomplaints.admin.cam.ac.uk/files/procedure_on_student_harassment_and_sexual_misconduct_with_explanatory_notes_-_2019.pdf (accessed 6 June 2019).

Durham University (2019) Policies and Strategies. Available at https://www.dur.ac.uk/university.calendar/volumei/policies_and_strategies/#faq4690 (accessed 2 June 2019).

The University of Edinburgh (2018) Code of Student Conduct. Available at https://www.ed.ac.uk/files/atoms/files/codeofstudentconduct.pdf (accessed 3 June 2019).

The University of Edinburgh (2017) Sexual Assault and Harassment Guidance. Available at https://www.ed.ac.uk/students/health-and-wellbeing/support-in-a-crisis/sexual-assault-and-harassment (accessed 3 June 2019).

University of Glasgow (2018) Alleged Misconduct Offenses That May Also Be Criminal Offenses. Available at https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/senateoffice/studentcodes/students/studentconduct/criminaloffence/ (accessed 3 June 2019).

Imperial College London (2018) Ordinance E3 Student Complaints Procedure. Available at https://www.imperial.ac.uk/media/imperial-college/administration-and-support-services/secretariat/public/college-governance/charters-statutes-ordinances-regulations/ordinances/Ordinance-E3.pdf (accessed 4 June 2019).

King’s College London (2017) G27 Academic Regulation (Appendix). Available at https://www.kcl.ac.uk/campuslife/acservices/Academic-Regulations/assets-17-18/G27.pdf (accessed 8 June 2019).

King’s College London (2017) Misconduct Guidance. Available at https://www.kcl.ac.uk/aboutkings/orgstructure/ps/acservices/conduct/201718-documents/misconduct-guidance.pdf (accessed 8 June 2019).

Lancaster University (2019) Response to Bullying, Harassment and Sexual Misconduct Policy. Available at https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/media/lancaster-university/content-assets/documents/strategic-planning--governance/publication-scheme/5-our-policies-and-procedures/Bullying-Harassment-and-Sexual-Misconduct.pdf (accessed 8 June 2019).

University of Leeds (2018) Policy on Dignity and Mutual Respect. Available at http://www.leeds.ac.uk/secretariat/documents/dignity_and_mutual_respect.pdf (accessed 4 June 2019).

The London School of Economics and Political Science (2018) Sexual Harassment and Sexual Violence Policy. Available at https://info.lse.ac.uk/staff/services/Policies-and-procedures/Assets/Documents/harVioPol.pdf (accessed 6 June 2019).

The University of Manchester (2019) Dignity at Work and Study Policy. Available at http://documents.manchester.ac.uk/display.aspx?DocID=22734 (accessed 7 June 2019).

The University of Nottingham (2019) Policy on Identifying and Handling Cases of Sexual Misconduct. Available at https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/governance/documents/sexual-misconduct-policy.pdf (accessed 8 June 2019).

The University of Nottingham (2018) Code of Discipline for Students. Available at https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/governance/documents/code-of-discipline.pdf (accessed 8 June 2019).

University of Oxford (2017) University Policy and Procedure on Harassment. Available at http://www.admin.ox.ac.uk/eop/harassmentadvice/policyandprocedure/ (accessed 5 June 2019).

Queen Mary University of London (2018) Code of Student Discipline. Available at http://www.arcs.qmul.ac.uk/media/arcs/policyzone/27-Code-of-Student-Discipline-2018.pdf (accessed 7 June 2019).

University of St Andrews (2018) Sexual Misconduct Policy Statement. Available at https://www.st-andrews.ac.uk/students/advice/personal/sexual-misconduct/policy-statement/ (accessed 4 June 2019).

University of Sheffield (2019) Regulation XXII: Regulations Relating to the Discipline of Students. Available at https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/polopoly_fs/1.663728!/file/XXII_regulations-relating-to-the-discipline-of-students.pdf (accessed 8 June 2019).

University of Southampton (2019) Dignity at Work and Study Policy. Available at https://www.southampton.ac.uk/diversity/policies/dignity_at_work.page (accessed 8 June 2019).

University College London (2018) UCL Academic Manual 2018–2019 Section 8: Disciplinary Code and Procedure in Respect of Students. Available at https://www.ucl.ac.uk/academic-manual/sites/academic-manual/files/section_8_student_disciplinary_procedure.pdf (accessed 6 June 2019).

The University of Warwick (2018) Reg. 23 Student Disciplinary Offences. Available at https://warwick.ac.uk/services/gov/calendar/section2/regulations/disciplinary/ (accessed 2 June 2019).

United States

Brown University (2016) Sexual and Gender-Based Harassment, Sexual Violence, Relationship and Interpersonal Violence and Stalking Policy. Available at https://www.brown.edu/about/administration/title-ix/policy (accessed 15 May 2019).

California Institute of Technology (2018) Sexual and Gender-Based Discrimination and Harassment and Sexual Misconduct. Available at http://hr.caltech.edu/documents/2925/caltech_institute_policy-sexual_and_gender_based_discrimination_and_harrassment_and_sexual_misconduct.pdf (accessed 27 May 2019).

The University of California (2018) Sexual Violence and Sexual Harassment. Available at https://policy.ucop.edu/doc/4000385/SVSH (accessed 1 June 2019).

Carnegie Mellon University (2016) Sexual Harassment and Sexual Assault. Available at https://www.cmu.edu/policies/administrative-and-governance/sexual-harassment-and-sexual-assault.html (accessed 30 May 2019).

The University of Chicago (2018) University of Chicago Policy on Harassment, Discrimination, and Sexual Misconduct. Available at https://harassmentpolicy.uchicago.edu/policy/ (accessed 30 May 2019).

Columbia University (2018) Gender-Based Misconduct Policy and Procedures for Students. Available at http://www.columbia.edu/cu/studentconduct/documents/GBMPolicyandProceduresforStudents.pdf (accessed 15 May 2019).

Cornell University (2019) Prohibited Bias, Discrimination, Harassment, and Sexual and Related Misconduct. Available at https://www.dfa.cornell.edu/sites/default/files/vol6_4.pdf (accessed 1 June 2019).

Cornell University (2014) Full Text of Student Procedures. Available at http://titleix.cornell.edu/procedure/fulltext/ (accessed 1 June 2019).

Duke University (2019) Student Sexual Misconduct Policy and Procedures: Duke’s Commitment to Title IX. Available at https://studentaffairs.duke.edu/conduct/z-policies/student-sexual-misconduct-policy-dukes-commitment-title-ix (accessed 30 May 2019).

Harvard University (2017) Sex and Gender-Based Harassment Policy. Available at https://hwpi.harvard.edu/files/titleix/files/harvard_sexual_harassment_policy_021017_final.pdf (accessed 15 May 2019).

Johns Hopkins University (2017) Sexual Misconduct Policy and Procedures. Available at https://sexualassault.jhu.edu/policies-laws/ (accessed 18 May 2019).

Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2018) II (23). Sexual Misconduct. Available at https://handbook.mit.edu/sexual-misconduct (accessed 18 May 2019).

The University of Michigan (2019) The University of Michigan Interim Policy and Procedures on Student Sexual and Gender-Based Misconduct and Other Forms of Interpersonal Violence. Available at https://studentsexualmisconductpolicy.umich.edu/files/smp/SSMP-Policy-PDF-Version011519.pdf (accessed 30 May 2019).

New York University (2018) University Policies: Sexual Misconduct, Relationship Violence, and Stalking Policy. Available at https://www.nyu.edu/content/dam/nyu/compliance/documents/SexualMisconductPolicy.April%202018.pdf (accessed 28 May 2019).

Northwestern University (2018) Comprehensive Policy on Sexual Misconduct. Available at https://www.northwestern.edu/sexual-misconduct/docs/sexual_misconduct_policy.pdf (accessed 28 May 2019).

The University of Pennsylvania (2015) Student Disciplinary Procedures for Resolving Complaints of Sexual Assault, Sexual Violence, Relationship Violence and Stalking. Available at https://almanac.upenn.edu/archive/volumes/v61/n20/pdf/012715supplement.pdf (accessed 5 July 2019).

The University of Pennsylvania (2019) Sexual Misconduct Policy, Resource Offices and Complaint Procedures. Available at https://almanac.upenn.edu/uploads/media/OF_RECORD_Sexual_Misconduct_supplement-Web.pdf (accessed 5 July 2019).

Princeton University (2019) Rights, Rules, Responsibilities 2019. Available at https://rrr.princeton.edu/university#comp13 (accessed 15 May 2019).

Stanford University (2016) Stanford Student Title IX Investigation & Hearing Process. Available at https://stanford.app.box.com/v/student-title-ix-process (accessed 5 July 2019).

Stanford University (2016) 1.7.3 Prohibited Sexual Conduct: Sexual Misconduct, Sexual Assault, Stalking, Relationship Violence, Violation of University or Court Directives, Student-on-Student Sexual Harassment and Retaliation. Available at https://adminguide.stanford.edu/chapter-1/subchapter-7/policy-1-7-3 (accessed 5 July 2019).

The University of Texas at Austin (2018) Prohibition of Sex Discrimination, Sexual Harassment, Sexual Assault, Sexual Misconduct, Interpersonal Violence, and Stalking. Available at https://policies.utexas.edu/policies/prohibition-sex-discrimination-sexual-harassment-sexual-assault-sexual-misconduct (accessed 1 June 2019).

University of Wisconsin-Madison (2018) UW-Madison Policy on Sexual Harassment and Sexual Violence. Available at https://compliance.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/102/2018/01/UW-Madison-Policy-on-Sexual-Harassment-And-Sexual-Violence-January-2018.pdf (accessed 28 May 2019).

Yale University (2019) Yale Sexual Misconduct Policies and Related Definitions. Available at https://smr.yale.edu/find-policies-information/yale-sexual-misconduct-policies-and-related-definitions (accessed 15 May 2019).

Yale University (2015) UWC Procedures. Available at https://uwc.yale.edu/policies-procedures/uwc-procedures (accessed 15 May 2019).

Yale University (2015) Statement on Confidentiality of UWC Proceedings. Available at https://uwc.yale.edu/policies-procedures/statement-confidentiality-uwc-proceedings (accessed 15 May 2019).

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/IntJlCrimJustSocDem/2020/3.html