|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy |

Life in the Shadow Carceral State: Surveillance and Control of Refugees in Australia

Anthea Vogl and Elyse Methven

University of Technology Sydney, Australia

|

Abstract

This article critically examines techniques employed by the Australian

state to expand its control of refugees and asylum seekers

living in Australia.

In particular, it analyses the operation of Australia’s unique Asylum

Seeker Code of Behaviour, which

asylum seekers who arrive by boat must sign in

order to be released from mandatory immigration detention, with reference to an

original

dataset of allegations made under the Code. We argue that the Code and

the regime of visa cancellation and re-detention powers of

which it forms a part

are manifestations of what Beckett and Murakawa call the ‘shadow carceral

state’, whereby punitive

state power is extended beyond prison walls

through the blurring of civil, administrative and criminal legal authority. The

Code

contributes to Australia’s apparatus of refugee deterrence by adding

to it a brutal system of surveillance, visa cancellation

and denial of services

for asylum seekers living in the community.

Keywords

Bridging visas; asylum seekers; refugees; shadow carceral state; Code of

Behaviour; crimmigration.

|

Please cite this article as:

Vogl A and Methven E (2020) Life in the shadow carceral state: Surveillance and control of refugees in Australia. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 9(4): 61-75. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.1690

Except where otherwise noted, content in this journal is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence. As an open access journal, articles are free to use with proper attribution.

ISSN: 2202-8005

In December 2013, Scott Morrison, Australia’s then Minister for Immigration and Border Protection, announced that asylum seekers living in the community would be subject to a new Code of Behaviour (Morrison 2013). Morrison first raised the idea of a ‘behaviour protocol’ exclusively for asylum seekers released from detention in February 2013 when as Shadow Minister for Immigration he was interviewed by talkback radio host, Ray Hadley. Responding to questions relating to an alleged indecent assault of a university student in her dormitory by an asylum seeker, Morrison stated (Ray Hadley Show 2013):

There should be a behaviour protocol that anyone released in the community has to adhere to. There should be a complaints mechanism for people who are concerned about things to be able to report these. Those incidents should be reported; they should be transparent. I mean there are no checks and balances here Ray. They just dump people in the community because they can’t control the borders ... it’s all no care, and all no responsibility.

The Code was introduced under the Migration Amendment (Bridging Visas – Code of Behaviour) Regulation 2013 (Department of Immigration and Border Protection 2013). Those subject to the Code—asylum seekers who travel to Australia by boat—are one of the most maligned and demonised populations in contemporary Australian politics. They are variously characterised in political rhetoric, on talkback radio and in tabloid commentary as a threat to national security, queue-jumpers, criminals, sexual deviants and ‘boat people’. Successive governments have implemented punitive policies purportedly to deter asylum seekers from reaching Australia via sea. The Code of Behaviour comprises one of the many ‘layers’ of state-sanctioned violence inflicted on those who seek asylum in Australia (Giannacopoulos 2017). This group is also subject to Australia’s deterrence apparatus, which includes mandatory indefinite detention, possible transfer to ‘offshore’ detention camps in Papua New Guinea or Nauru and a regime of temporary protection for unauthorised ‘onshore’ asylum seekers.

Signing the Code is a precondition for any asylum seeker to be released from detention on a bridging visa, at the Minister’s discretion. In general, bridging visas serve to temporarily regularise the legal status of people awaiting the resolution of a visa application. For unlawful non-citizens, they allow for release from otherwise mandatory detention. The Explanatory Statement to the Code states that it will make asylum seekers ‘more accountable for their actions’ (Explanatory Statement 2013). Once signed, asylum seekers are subject to a regime of monitoring and reporting requirements mainly administered by caseworkers tasked with ensuring that asylum seekers understand the Code’s provisions and comply with its terms. Under the Code, asylum seekers are not only forbidden from disobeying any ‘Australian laws’, they are also subject to additional behavioural standards or ‘expectations’ that do not apply to the community at large, which are assessed and enforced by departmental officers and immigration service providers.

As such, the Code operates in ways that both duplicate and exceed the scope of Australian criminal law, but being an administrative power, it evades protections ordinarily attached to criminal prosecutions. A breach of the Code may be found in relation to an alleged criminal offence even where the criminal proceedings for the offence have not been resolved, where the charge has been withdrawn or where the asylum seeker has been acquitted of the offence altogether. If the Code’s provisions are deemed to be breached, income support may be reduced or stopped, an existing bridging visa may be cancelled, or an asylum seeker may be detained in onshore detention or transferred to an offshore detention centre. The Code contributes to and expands the broader Australian apparatus designed to deter future asylum seekers by adding to it a brutal system of surveillance, visa cancellation and denial of services for asylum seekers living in the community. In this way, the Code extends state power and control over the lives of asylum seekers beyond the walls of mandatory, indefinite detention centres while steadfastly preserving the threat of re-detention or deportation.

This article critically examines the Code of Behaviour and situates it within the broader bridging visa regime that applies to asylum seekers living in Australia. We argue that the Code, and the broader regime of which it is a part, are clear manifestations of what Beckett and Murakawa (2012) have theorised as ‘the shadow carceral state’. They explain this ‘less visible’ state development as one that ‘makes use of legally liminal authority, in which expansion of punitive power occurs through the blending of civil, administrative and criminal law authority’, whereby punishment is imposed ‘beyond prison walls’ (Beckett and Murakawa 2012: 222 emphasis in original). The Code has received little attention from criminological, critical migration and refugee studies scholars, with much scholarship in this field being concentrated on the severe harms of mandatory detention and the ever-expanding visa cancellation powers on ‘character’ grounds in s 501 of the Migration Act 1958 (Cth) (‘Migration Act’) (e.g., Billings 2015, 2019; Grewcock 2011).

The bridging visa regime, the Code and attendant visa cancellation powers demonstrate how administrative legal authority has been mobilised in what was once a criminal context—the investigation and punishment of breaches of the criminal law—without affording asylum seekers the most basic substantive and procedural safeguards attached to criminal proceedings. At the same time, the cancellation powers represent ‘the extension of the criminal law into (formerly) administrative ... contexts’ by co-opting police to report on Code breaches while providing a means by which immigration sanctions can be applied to alleged criminal offending. This significantly increases the ‘capacity of the state to punish’—a phenomenon Beckett and Murakawa (2012: 232) label ‘administrative law by adaptive criminalisation’. Read as a whole, the bridging visa conditions and cancellation powers based on criminal or behavioural grounds are central features of the expanding carceral state experienced by asylum seekers in Australia, even once they have been released from immigration detention.

In analysing the bridging visa regime, this article focuses on the growing use of broad visa cancellation powers against asylum seeker bridging visa holders. It addresses cancellation both under the Code and on criminality grounds (including on the basis of criminal charges under s 116(g) of the Migration Act) since allegations under the Code were used to trigger broader cancellation powers. In particular, it presents data accessed via Freedom of Information (FOI) requests that chart 499 uses of Code powers from 2014–2016 (Department of Immigration and Border Protection 2016b). By comparing the Code’s ‘expectations’ to the contents of federal and state criminal laws, we demonstrate the Code’s vague and amorphous nature. Its terms are ostensibly informed by, but also depart from, existing criminal offences and are sometimes entirely inconsistent with existing criminal law principles and protections. We show that the Code operates at the intersection of criminal and administrative laws and powers; it is implicated in the imposition of both administrative and criminal punishments on asylum seekers for allegations ranging from offensive language and driving without a license, to aggravated assault.

Beckett and Murakawa (2012: 224) trace and theorise the operation of the shadow carceral state to, as they put it, develop a more robust and scholarly understanding of the penal state ‘that is independent of official claims about what is and is not punishment’. Correspondingly, we adopt their analysis here to explain the expansion of the carceral state as it applies to asylum seekers. Attending to the expansion of the shadow carceral state explains state surveillance and control of asylum seekers outside of the physical space of immigration detention. The Code is a mechanism by which the territorial border as a site of heightened state power has been expanded, discursively and practically, across the interior of Australia. The targeting of the Code to a specific subset of non-citizens—asylum seekers who travel to Australia by boat—serves as an omnipresent reminder that for them ‘the border is everywhere’ (Simon 1995: 635). The visa cancellation powers and bridging visa regimes deploy the spectre of re-detention combined with limited access to social and welfare services to punish and ultimately exclude the asylum seeker population ‘released’ into the Australian community.

The remainder of the article addresses the above in two parts. Part I explains the bridging visa regime as it applies to asylum seekers living in the community and analyses the Code of Behaviour and other relevant cancellation powers as manifestations of the shadow carceral state. Part II examines practices of bridging visa cancellation, and the policing and surveillance of Bridging Visa Class E (BVE) holders. To this end, we analyse a dataset that charts the use of the visa cancellation powers from 2014–2016 across 499 alleged breaches of the criminal law or the Code. In the context of extremely limited available information about the regulation of bridging visa holders, this data provides insight into the punishment and precarity embedded into the lives of asylum seekers in Australia.

Part I: The Bridging Visa Regime, Cancellation Powers and the Code of Behaviour

The Bridging Visa Regime for Asylum Seekers Living in the Community

The bridging visa regime, in particular the Code and BVE cancellation powers, are core strategies used by the state to deter, control and punish asylum seekers in a way that blurs migration control and criminal punishment (Bosworth 2017). While the BVE was introduced as part of an ‘emptying out’ of detention centres (Vogl 2019), it is best understood as a practice of the shadow carceral state, which extends the apparatus of exclusion and enables the ‘harms of detention to appear in new forms’ (Giannacopoulos and Loughnan 2019). Australian immigration law provides for a range of bridging visas, which regularise the legal status of people awaiting resolution of their immigration matters, either via the grant of a substantive visa or departure or deportation from Australian territory. BVEs allow people with no lawful status either to avoid mandatory detention or to be released from detention while they apply for a substantive visa or arrange to leave Australia. There are two classes of BVE: ‘general’ and ‘protection’ (050 and 051). Both categories are for people who are formally identified as unlawful non-citizens, including asylum seekers classified as ‘unauthorised’ or (in the language of the government) ‘illegal maritime arrivals’. Both terms—illegal and unauthorised—carry a powerful yet deceptive symbolic message: that these individuals are not legitimate members of Australian society. Further, due to a permanent statutory bar on asylum seekers who arrived by boat applying for any form of visa without the Minister’s permission, the granting of a BVE is only possible at the Minster’s non-reviewable and non-compellable discretion (Migration Act s 46A).

The number of BVEs issued to asylum seekers and the size of the group living on BVEs are significant. The dataset we address covers the period from 26 June 2014 to 1 July 2016, during which approximately 57,430 BVEs were granted to asylum seekers in the community.[1] As at 30 June 2016, the number of asylum seekers living on bridging visas in the community was 28,163. The asylum seeker population on BVEs in Australia has since decreased to 14,507.[2]

Immense precarity and socio-economic vulnerability have become the trademarks of the BVE. Alongside the Code and visa cancellation powers, the other continuing feature of the bridging visa regime is the systemic denial of access to welfare services, employment rights or both. The denial of the rights to work and access to welfare support (the ‘no work, no income, no Medicare’ trifecta)[3] characterised the BVE category in the 2000s (Markus and Taylor 2006; McNevin and Correa-Velez 2006).[4] The conditions attached to contemporary BVEs, including the removal of access to welfare support, have been analysed as a form of deportation by destitution (Refugee Council of Australia 2018b), or, as Hekmat (2018) has written, weaponising food in order to pressure asylum seekers to leave. This strategy was made explicit in the 2018 government announcement that income support for all BVE holders with work rights would be withdrawn, regardless of whether or not those affected by the changes had a job or access to work (Refugee Council of Australia 2018b). While the shadow carceral state expels marginalised individuals from the community by intensifying the penal power of various institutional sites and actors, the ‘attrition’ of access to government services and welfare simultaneously contributes to physical exclusion through encouraging ‘voluntary departures’ from Australia ‘cloaked in a mantle of individual choice’ (Weber and Pickering 2014; Weber 2019a: 230).

Scholars writing about the harms of Australia’s bridging visa regime have highlighted how the conditionality of these visas, alongside the denial of work and welfare rights, has led to a sense of insecurity and extreme marginalisation among people seeking asylum (Fleay and Hartley 2016). Hekmat (2018) documented that more than 10 asylum seekers on bridging visas committed suicide in the four years to April 2018, and numerous others attempted suicide. The challenges posed by these conditions are exacerbated by the long waits for the resolution of refugee claims and the short-term nature of BVEs, often granted for periods of three or six months. Despite this confluence of conditionality, welfare and rights-denial, BVE holders continue to find ways to negotiate visa restrictions and make their lives livable to the greatest extent possible under the immense emotional, social, economic and personal impact of the regime (Hartley and Fleay 2017; Weber 2019a).

These visas and the exploitation of the discretion that governs their length and conditions exemplify how socio-economic restrictions are used as technologies of state punishment (Giannacopoulos 2017). Weber’s (2013) account of the structurally embedded border helps in understanding this visa as a key strategy of onshore refugee deterrence. Her identification of two distinct dimensions of the structurally embedded border, namely ‘the assembling of public and private agencies into “migration policing networks” and the systematic withdrawal of services to various categories of non-citizens, aimed at conserving resources for citizens and generating “voluntary” departures’ (Weber 2019b, 2013) can be mapped directly onto the operation of the bridging visa regime. In particular, the dramatic ‘net-widening’ effect the BVE category has had on the networks of individuals who both provide and withdraw services, and—as explored in the next section—police and enforce border controls, is key to the structural embedding of the border for asylum seekers in the Australian community. Indeed, Boon-Kuo (2017), in analysing the discretion and conditionality that governs BVEs, describes this visa category as an example of the state mobilising a ‘legal status as a mechanism of selective and arbitrary control’ (113) such that ‘it is not legal status itself that is important for release from detention’, but the conditions imposed on that status (123).

Bridging Visa Cancellation Powers: Section 116 of the Migration Act and the Code of Behaviour

The conditions outlined above characterise the BVE regime before the extensive BVE cancellation provisions are taken into account. To be released from detention on a BVE is to live with the constant possibility of either visa non-renewal or cancellation. Bui, a researcher and activist, describes BVE holders as being left in a state of permanent limbo where ‘the threat of re-detainment is omnipresent’ (Davey 2015: para 23). We set out the content of key cancellation powers here, followed by our analysis of their operation.

Beckett and Murakawa’s account of the shadow carceral state maps neatly onto BVE cancellation powers. The content and operation of the cancellation powers and Code of Behaviour are marked by an ‘institutional annexation of sites and actors beyond what is legally recognized as part of the criminal justice system’, such as immigration officers, caseworkers, migration tribunals and non-criminal detention facilities; the powers operate in ‘opaque, entangling ways’ so that over time, ‘seemingly small incursions compound the heightened surveillance that comes with institutional enmeshment’; and the Department’s use of the Code heightens immigration oversight and enforcement over crimes and criminal law (Beckett and Murakawa 2012: 222–227).

Alongside the wide-ranging visa cancellation powers based on a criminal conviction, the Migration Act includes lesser-known and expansive grounds for the cancellation of temporary visas under s 116. Section 116(g) of the Migration Act sets out that a visa may be cancelled if a prescribed ground for cancellation applies to the holder. Regulation 2.43 of the Migration Regulations 1994 (Cth) prescribes that the Minister may cancel a BVE if satisfied that the holder has been charged with (but not convicted of) an offence; or convicted of an offence against a law of the Commonwealth, a state, a territory or another country. These powers came into effect in June 2013, justified on the grounds that ‘[t]he Government has become increasingly concerned about unauthorised arrivals who engage in criminal conduct after being released into the community on BVEs while they await for the claims to be assessed’ (Explanatory Statement, Migration Amendment (Subclass 050 and Subclass 051 Visas) Regulation 2013 (Cth) n.d.). The fact that this power can be invoked on the basis of criminal charges and no evidence of guilt or conviction exemplifies a foundational aspect of the shadow carceral state: that institutions, which although ‘not officially recognized as “penal” ... have nonetheless acquired the capacity to impose punitive sanctions—including detention—even in the absence of criminal conviction’ (Beckett and Murakawa 2012: 222 our emphasis).

The Code of Behaviour is the other key component of bridging visa cancellation powers. The Code, as described above, enlarges the already vast discretions relating to bridging visa cancellation, and applies to all so-called unauthorised maritime arrivals (UMAs)[5] who apply for or seek to renew a bridging visa. The Code details six expectations regarding how UMAs must behave ‘at all times while in Australia’. The expectations are repetitive and overlapping, and set out that asylum seekers:

• must not disobey any Australian laws, including Australian road laws;

• must not make sexual contact with another person without that person’s consent, regardless of their age;

• must not take part in, or get involved in any kind of criminal behaviour;

• must cooperate with all lawful instructions given by police and government officials and all reasonable requests from the Department of Home Affairs or its agents;

• must not harass, intimidate or bully any other person; and

• must not engage in any anti-social or disruptive activities that are inconsiderate, disrespectful or threaten the peaceful enjoyment of other members of the community (emphasis in the original Code).

The final two expectations are similar to broad public order-type offences but also create new behavioural requirements that do not replicate the criminal law (e.g., there is no offence of ‘bullying’ in Australia). The Code defines ‘anti-social’ as an action that is ‘against the order of society’ that may include spitting, swearing in public or actions that ‘other people might find offensive’. ‘Bullying’ is defined as including anything from attacking someone verbally or physically, to spreading rumours, or excluding someone from a group or place on purpose. These expectations purport to establish ‘behavioural standards expected by the Australian community’ (Department of Immigration and Border Protection 2015: 3), but somewhat paradoxically, apply exclusively to asylum seekers and exceed the content of the criminal (and for that matter, civil) law. They exemplify how the shadow carceral state adopts and expands the scope of already ‘fuzzy definitions of crime’ (Beckett and Murakawa 2012: 222) (or in the Code’s case, ‘breaches’), and transfers the policing and punishment of supposed behavioural breaches to administrative and executive realms of governance. The Code functions as an especially severe example of ‘crimmigration’ (the criminalisation of immigration law: Stumpf, 2006) in explicitly using immigration law and regulations to police and punish asylum seekers. Likewise, the blurring of criminal and administrative legal processes increases the ability of the state to punish asylum seekers by undermining ‘the capacity of immigrants to assert their rights and avoid punishment in both settings’ (Beckett and Murakawa 2012: 232).

Part II: Visa Cancellation Data and the Shadow Carceral State in Action

In late 2016, the Department partially fulfilled our FOI request seeking access to the total number of allegations of breaches under the Code from June 2014 to July 2016; the nature of the alleged breaches; a description of behaviours giving rise to a breach; a description of the complainant/reporter; and, the outcome of the allegation including any action taken by the Department where a breach or no breach was found.[6] The Department released a table of 499 alleged breaches of the Code over an approximate two-year period commencing in April 2014.[7] The table includes cancellations made under ‘non-Code powers’, as the Department puts it, primarily under s 116(g) of the Act outlined above. This part of the article analyses what the data reveal about the operation of the Code, the sanctions attached to breaches and the use of visa cancellation powers against asylum seekers living in the community.

Before proceeding to our analysis, it is noteworthy that the data released by the Department are imperfect and suffer from a range of ‘human errors’ and gaps. The table appears to be the Department’s primary record of BVE cancellations, filled in inconsistently by (one presumes) multiple departmental officers. For example, not all columns have been completed for every allegation. Additionally, there are errors such as incomplete dates and spelling mistakes in the information recorded in the table. There are other limitations to using state-aggregated data. For our analysis, we note its tendency to abstract away from complicated, individual experiences into broad, inflexible categories, which in this case includes categories of nationality, breach type and outcome.

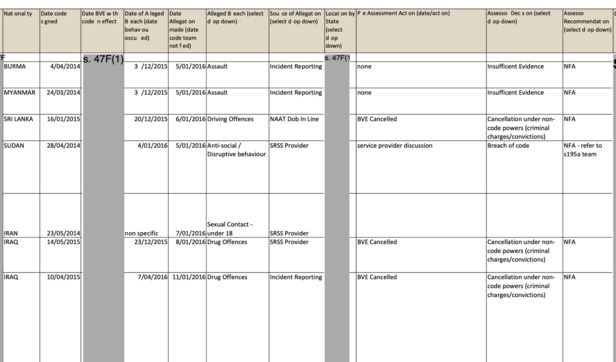

Figure 1: Sample of departmental tabulated data on code breaches

The dataset is nonetheless valuable. Unlike many available government records, the table lists outcomes, allegations and source of allegation, even where cancellation did not take place. However, the table’s inclusion of information that extends beyond where cancellations were made, to include where allegations were not upheld provides a more nuanced picture of cancellation practices than was previously available. Thus, attending to this ‘top-level’ dataset is valuable, including where it is imperfect.

Data and Analysis

Cancellations Based on Criminal Charges or Convictions

Overall, the dataset reveals highly frequent use of s 116(g) cancellation powers against BVE holders during the period covered by the FOI. Critically, it also confirms that the s 116(g) cancellation power is used to cancel BVEs where the BVE holder is charged with criminal conduct, but no charge is prosecuted, or the applicant is ultimately acquitted (Neave 2016: 21). Of the 499 allegations of a possible breach recorded, at least 159 allegations (one in three or 32%) resulted in cancellations or non-renewals of BVEs under non-Code powers, including under s 116(g). The data do not indicate whether allegations of a breach of the Code were made before or following any criminal charge or conviction. If a person’s BVE is cancelled, they become an ‘unlawful non-citizen’ and are subject to immigration detention (Neave 2016: 4; see also Morrison 2013).

In interpreting the 159 allegations that resulted in BVE cancellations, it is essential to give some sense of the so-called allegations and grounds recorded for cancellation. In many cases, this information is unclear. The exact basis for cancellation (outside the use of non-Code powers or s 116(g)) is not listed in every instance. However, in 55 instances (35%), the table clearly records that cancellation took place on the basis of a criminal charge rather than a conviction. The remaining instances (65%) do not specify the basis for cancellation.

Type and Occurrence of Allegations

In the data, the ‘type’ of the alleged breach is only categorised in a very general manner (listed in a column titled ‘alleged breach’), and further details about each allegation are not recorded. As such, it is difficult to know anything beyond the broad type of each allegation. The ‘types’ of allegation can be divided into two groups: those that reflect existing criminal offences (e.g., ‘fraud’) and those that reflect non-criminal conduct offences imposed by the Code (e.g., ‘harass/intimidate/bully’). Despite the minimal detail in the allegations, they nonetheless are evidence of the net-widening effect that the amorphous and ill-defined terms of the Code have had on the policing, surveillance and punishment of asylum seekers. Allegations that mirrored the expectations of the Code but either exceeded or did not immediately correspond with a recognisable Commonwealth or state criminal offence included, but were not limited to:

• disturbance,

• dishonesty (public official),

• harass/intimidate/bully,

• self-harm,

• uncooperative to resolution of status,

• anti-social/disruptive behaviour.

Driving offences made up over a quarter (28% or 139/499) of all alleged breaches. What constitutes a ‘driving offence’ is not described in the data. If the term ‘driving offence’ is to be construed in light of the Code’s prohibition against breaching ‘road laws’, driving offences could range from conduct as serious as dangerous driving causing death (Crimes Act 1900 (NSW) s 52A) to minor parking and traffic breaches dealt with by an infringement notice. Of the 139 allegations based on driving offences, 20 per cent led to BVE cancellation. The next highest incidence of alleged breaches was ‘assault’ (14%), followed by ‘domestic violence’ (10%) and the especially elusive ‘dob-in allegation’ (6%).

The Code directly expands the operation of the shadow carceral state insofar as it allows for severe forms of punishment for minor or fuzzy ‘behavioural breaches’ while circumventing the common law rights and due process attached to criminal proceedings (Beckett and Murakawa 2012: 232). Notable among those ‘fuzzier’ breach categories for BVE holders were allegations of ‘anti-social/disruptive behaviour’, ‘public nuisance’ and causing a ‘disturbance’. The data recorded nine alleged breaches of ‘anti-social/disruptive behaviour’, six alleged breaches of ‘public nuisance’ and four allegations of causing a ‘disturbance’ (comprising a total of 19 or 4% of incidents). Several observations arise from the nature and enforcement of these breach categories. First, it is unclear how the Department distinguishes ‘anti-social’ behaviour from ‘public nuisance’. Crimes prohibiting disorderly conduct, public nuisance and offensive behaviour exist in each Australian state and territory (Methven 2017); however, there are no crimes that explicitly prohibit ‘anti-social’ behaviour. It could be that what constitutes a ‘public nuisance’ (and perhaps also ‘anti-social’ behaviour) for the purposes of the Code is informed by the various and notably divergent state definitions of these offences. However, the extent to which the Department relies on criminal definitions of public nuisance in determining how to respond to Code breaches is unclear.

More astonishingly, ‘self-harm’ is listed within the data as an alleged ‘breach’ of the Code. This demonstrates the criminalising lens applied to persons potentially in acute need of mental health treatment or care, particularly in light of the high mental illness and self-harm rates documented among asylum seekers who have been subject to Australia’s detention regime (Steel et al. 2006). The listing of self-harm as a breach of the Code designates asylum seekers’ illnesses (which may be caused or partially caused by their indefinite detention and degrading treatment by the Australian government) not as something requiring treatment and compassion, but rather, as a sign of deviance and criminality, and as the basis for further state discipline and incarceration. Current Department of Home Affairs Minister Peter Dutton has gone so far as to characterise incidents of self-harm as an attempt to exert pressure on the Australian government to change its border protection measures, encouraged by refugee advocates (Keany 2016). The Code introduces this view of self-harm into a formal administrative instrument of regulation and with it the possibility of BVE cancellation and re-detention.

The categories of breaches under the Code and its ‘perverse preoccupation with the subject of manners [and behaviour] are also consistent with colonial, civilising discourses’, which require racialised ‘others’ to learn from and adopt the customs of the new host state over their own cultures (Vogl and Methven 2015: 179). This should come as no surprise in an Australian settler state, which was ‘founded and sustained on colonial violence’ (Giannacopoulos 2017, Tofighian 2020) against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, including massacres and deaths in custody, a denial of culture and resources, dispossession, disproportionate institutionalisation and over-incarceration, each justified ‘as a “civilising” strategy for the creation of the settler state’ (Nettleback and Ryan 2018: 49).

Asylum seekers are depicted via the Code’s list of expectations as requiring ‘familiarisation with Australian societal standards and codes of behaviour’. In addition, the Code allows Status Resolution Support Services (SRSS) providers and the Department ‘to remind people of the Code’ and, according to former Immigration Minister Scott Morrison, ‘mak[e] people aware of what’s expected of them, where complaints or other things are brought to the service provider’s attention’ (Morrison 2013: para. 128). It is these ‘behavioural’ breaches that—according to the government—the Code was specially designed to target, given that the Department already had the power to cancel or refuse to grant a BVE upon criminal charges being laid. The impenetrable and circuitous nature of the definitions relied on by the state to impose arbitrary punishments on non-citizens, in part borrowed from the criminal law but used and expanded in an immigration context, is a central feature of the shadow carceral state ‘characterized by institutional spread, legal fungibility, and opaque mechanisms’ (Beckett and Murakawa 2012: 222). While these breaches constituted a minority of allegations, the following section reveals their disciplinary and widespread effect.

Consequences and Sources of Allegations: Expanding Policing, Surveillance and Punishment

Read as a whole, it is clear that during the period covered by the data, Code powers were surprisingly not the mechanism used to cancel bridging visas. Rather, cancellation powers were overwhelmingly exercised using s 116(g) on the basis of criminal charges. Where a breach of the Code was found, and cancellation powers were not exercised, this was instead likely to result in a BVE holder being referred for a ‘counselling’ session with a department officer or a ‘discussion’ with their SRSS provider. Of the 192 allegations (38%) where it was found that the BVE holder breached the Code, is it clear that this breach resulted in a visa cancellation in only one instance (for a driving offence). In three instances, the Department noted that it was considering cancellation under powers specific to the Code (for self-harm, assault and anti-social/disruptive behaviour), and in 163 instances (84%), a referral for counselling or an SRSS discussion was made.[8] Of particular relevance is how the Code operates to surveil and punish asylum seekers for even the most minor breaches (or allegations of breaches) of ‘social order’ that may, as Morrison said, be ‘upsetting others in the community’ (Morrison 2013). The Department’s Annual Report explains that counselling sessions and discussions are aimed at ‘reinforc[ing] expected behavioural standards’ (Department of Immigration and Border Protection 2016a: 51). The significant implication here is that the Code is used to facilitate surveillance, policing and ‘monitoring’ at the same time as already existing statutory, criminal charge cancellation grounds are used to cancel bridging visas. Indeed, the role of the Code in facilitating surveillance, undertaken by those directly providing social and welfare services to asylum seekers—and enabling other cancellation powers—is also evident in the source of allegations recorded in the FOI dataset.

The Code is silent on who can police or report on ‘breaches’; however, through an earlier FOI request, the Department informed us that it expected to receive allegations through ‘a range of sources’ including ‘members of the public’, ‘service providers’, ‘police services’ and ‘other government agencies’. Hence, by signing the Code, asylum seekers become subject to the intrusive, omnipresent gaze of departmental officials, community organisations, law enforcement, their peers and the general Australian community. The column recording the source of allegations sheds further light on how the Code operates. It reveals that 61 per cent of allegations (301 out of 499) originated from organisations providing asylum seekers with resettlement services and assistance (SRSS providers). The next highest source was the ‘National Allegation Assessment Team Dob-in Line’, which was responsible for nine per cent of allegations. Police accounted for five per cent of allegations, and caseworkers accounted for another three per cent.[9]

The table reveals that charity and non-government settlement organisations are at the centre of the operation of both the Code and section 116(g) cancellations. The statistics regarding the source of allegations reinforce Weber’s account of the ever-expanding web of agents who police, surveil and report on asylum seeker and non-citizen populations—a network of policing and reporting much wider than networks of surveillance and law enforcement experienced by most (but not all) Australian citizens (Weber 2013). Gerard and Weber (2019: 268), in their exceptional study exploring the concept of ‘humanitarian borderwork’, examine how government-contracted NGOs providing services to unaccompanied minors ‘negotiate the tensions between humanitarianism and government imperatives towards the securitization of migration’. Their work brings to the fore how SRSS providers are directly implicated in ‘delivering the government’s securitization agenda’ as a result of requirements ranging from reporting any form of discipline child clients experience at school, to ‘teaching’ clients to live on the extremely meagre welfare funding provided to asylum seekers, as well as enforcing the Code of Behaviour (Gerard and Weber 2019: 276).

The conflicting obligations that caseworkers employed by SRSS providers owe to the Department on the one hand and the BVE holder on the other have largely remained unscrutinised. However, two contracts with SRSS providers released under FOI requests in September 2017 confirm that caseworkers are contractually obliged to assist BVE holders to ‘understand and comply with their obligations under the Code’, ensure they ‘understand the importance of their responsibility for adhering to acceptable standards of behaviour in the community, including those stipulated in the Code’ and make the Department ‘aware of any breaches of the Code’ (Department of Immigration and Border Protection 2014). This is in addition to the responsibility of SRSS caseworkers to provide orientation sessions for asylum seekers involving ‘basic information about rules and laws’ and ‘appropriate public behaviour’ (Department of Immigration and Border Protection 2014).

The contractual obligations to a large extent explain why so many reports of breaches of the Code emanate from SRSS providers. The SRSS contracts further corroborate our finding that SRSS caseworkers are the main source of surveillance, reporting and disciplining of asylum seekers for breaches of the Code. The contractual terms also demonstrate the significant overall impact of the Code for those required to sign it as a condition for release from detention. The Code looms large over asylum seekers’ lives and ‘has created a climate of fear among communities’ (Refugee Council of Australia 2018a), reinforcing the notion that they are ‘out of place’ within the Australian community. Asylum seekers are repeatedly reminded that the Australian community’s values are different to their own and must be adapted to; that it is their ‘responsibility’ to conform to these values; and that any failure to conform may lead to arbitrary, indefinite detention.

The conflicting role that SRSS providers play in supporting asylum seekers’ complex resettlement needs—while also policing, mandatorily reporting and responding to breaches of the Code—is especially troubling. Refugee advocate Pamela Curr has argued that many asylum seekers are afraid to disclose problems to caseworkers, fearing that the caseworker will report disclosures to the Department:

The asylum-seekers are really cursed. If they have an agency that’s looking after them and they go to that agency and say, ‘I’m feeling suicidal, I want to jump in front of a train, I can’t sleep, I’ve got voices in my head’—all the marks of mental ill-health—those agencies will notify the immigration department, and the next thing you know, the department will rock up and cart them off to detention. They’re in a real bind (Stott 2015: para 26).

Under a separate FOI request, we obtained several Migration Review Tribunal[10] decisions. One illustrative case demonstrates the Code’s expansion of the carceral state as well as its operation at the capacious junction of administrative and criminal laws. The case involved the review of a BVE cancellation of an applicant who had been charged under the Summary Offences Act 2005 (Qld) with ‘commit public nuisance’ and whose visa was cancelled on the basis of that charge. Significantly, at the time of the Migration Review Tribunal hearing in April 2015, the applicant’s criminal case for the same conduct was yet to be heard. Therefore, his criminal liability was not yet determined.

In the case before the Tribunal, the applicant and the police presented two very different versions of events. The applicant said that he had been drinking and had called the police because he was being attacked. He said that he ‘had signed the Department’s Code of Conduct and ha[d] not done anything wrong’. He had travelled to Australia alone, had no family members in Australia and did not have permission to work. According to police, the applicant was using offensive language and had threatened to stab them and another person. The applicant explained that he ‘ha[d] only drunk more alcohol since coming to Australia ... so he can sleep, a fact of which his counsellor is aware’. He said that ‘the cancellation of his visa and being in detention ha[d] affected him badly. He cannot sleep and has nightmares.’ In setting aside the cancellation decision and substituting it with a decision not to cancel, the Tribunal found the applicant’s version of events to be ‘plausible’; it also noted that the applicant’s charge was a summary offence, that it did not involve violence, that the applicant did not present ‘a risk to the community’ and was ‘extremely unlikely to get a custodial sentence’ (Tribunal Member Kay Ransome 2015).

The minor sentences (such as fines, community service or good behaviour bonds), if any, that many of the asylum seekers may receive if found guilty of their criminal charge stand in contrast to indefinite detention and possible deportation as a result of the visa cancellation power under s 116(g). Yet, as Beckett and Murakawa (2012: 224) highlight, legal doctrine persists in maintaining the official line that administrative penalties are ‘not punishment’ and upholds this illusion ‘by equating (only) criminal legal authority with punishment, and by deferring to legislative descriptions of sanctions as civil, administrative or criminal in nature’. An Ombudsman’s Report on these powers addressed how in such cases, the presumption of innocence is eroded while also noting the lack of proportionality where decisions are made ‘to cancel a visa under [regulation 2.43] in relation to charges that sit on the more minor end of the spectrum’ (Neave 2016: 8). The Ombudsman also cited anecdotal reports that ‘in some cases the department issued the [notice of intention to cancel] to the visa holder as they were leaving court having just been granted bail’, noting that one of the factors in bail grants is whether an unacceptable risk will be posed to the community (Neave 2016: 8).

While our data do not address the management of BVE cancellations and the consequences of these cancellations after they have been made, the Ombudsman’s Report into the exercise of section 116(g) shows that, due to gross delays and mismanagement of immigration detention, BVEs are not reissued (at the Minister’s discretion) even where the charges that formed the basis for the cancellation were dropped within the criminal justice system. This strikes as the most extreme failure of justice since the applicant is re-detained for actions that are judged by the criminal justice system as providing no basis for a conviction. At the same time, BVE cancellations endure while criminal charges are in motion. Thus, ‘due to delays in local court systems, people may have to wait months in detention before their charges can be heard by the courts’, adding to the uncertainty they face (Neave 2016: 20). This was the experience of the Sri Lankan asylum seeker whose alleged indecent assault in a university dormitory, outlined at the outset of this article, sparked Morrison’s call for the Code to be introduced. The asylum seeker languished three years not on remand, but rather in immigration detention before a court eventually found him not guilty of the indecent assault charge. Despite his acquittal, the Minister retained the power to cancel his visa under s 116(g) (AAP 2016) and the discretion to reissue it. While crimmigration scholarship has noted the theoretically stronger protection of liberty under criminal law and process (Stumpf 2006; Zedner 2010), the BVE holders in detention awaiting delayed criminal trials exist at the crossover of the worst excesses, mismanagement and injustices of both systems.

One of the challenges of reading the dataset outlined here is trying to map the intersection of criminal and immigration law within BVE cancellation practice. There is more work to be done and further data is required to interrogate the policing of the Code as well as the implications of breach allegations and visa cancellations. The statistics recounted here are not gendered and do not reveal other conditions on BVEs, such as work rights or access to the SRSS. Further pressing questions include: what interpretative materials decision-makers rely on when determining breaches; what opportunities BVE holders are given to respond to breach allegations; and whether any evidential rules or procedural safeguards are in place to protect against innocent persons being reported or punished under the Code.

Conclusion

Australia has attracted an international reputation for its harsh policies towards asylum seekers and has become a world leader in border externalisation practices aimed at preventing their arrival. At the same time, Australian governments have shown a preparedness to use their internal enforcement powers to expel non-citizens who commit criminal offences or violate their visa conditions. Border control practices that operate before and after arrival reflect the external and internal manifestations of the Australian border. Although openly coercive practices, such as maritime interdiction, mandatory and offshore detention and deportation, are the most visible and notorious aspects of Australia’s deterrence apparatus, new forms of internal border enforcement function to punish and exclude asylum seekers living in the community before their formal application is determined, as well as to compel compliance with migration management goals (including ‘voluntary’ deportation) (Weber and Pickering 2014).

This article has presented the Code of Behaviour and visa cancellation powers used against asylum seekers in the context of the broader BVE regime and its multiple means of policing and enforcing an internal border. It has begun the task of analysing how bridging visa cancellation powers and the Code of Behaviour are demonstrative of the shadow carceral state being deployed as a means of exclusion, deterrence and punishment. Common themes running through the language to describe crimmigration generally, and Beckett and Murakawa’s (2012: 222) shadow carceral state specifically, include a sense of opaqueness and darkness (i.e., in the shadows) on the one hand, and entangling, intertwining and fuzzy boundaries on the other. This sense of darkness and disordered, difficult-to-trace lines reflect how the Code and cancellation powers unsettle transparency or certitude about how, where and on what terms these prima facie immigration powers are being exercised, and on what basis they interact with other forms of governance—not least with the criminal law.

Our analysis has illuminated how technologies of control and surveillance, which co-opt an ever-broadening cast of government and non-government actors, are extended to asylum seekers living in the community. However, the exercise of the carceral powers outlined here does not necessarily lead to statutory prison terms but rather ensnares asylum seekers in administrative forms of punishment and detention outside of the (already imperfect) protections of the criminal justice system. Since most breaches of the Code resulted in counselling or a discussion with service providers, our dataset reveals the disciplining effects of the Code, even in the absence of a visa cancellation or other forms of penalty, let alone any form of criminal conviction. We have argued that the confluence of restrictive visa conditions, enhanced surveillance and policing as well as the dual assertion of administrative and criminal powers over asylum seekers has heightened the already substantial forms of state-sanctioned violence inflicted towards this population via Australia’s refugee deterrence apparatus.

AAP (2016) Asylum-seeker Cleared of Indecent Assault. 11 March. http://global.factiva.com/redir/default.aspx?P=sa&an=AAPBLT0020160311ec3b00001&cat=a&ep=ASE

Beckett K and Murakawa N (2012) Mapping the shadow carceral state: Toward an institutionally capacious approach to punishment. Theoretical Criminology 16(2): 221–244. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362480612442113

Billings P (2015) Whither indefinite immigration detention in Australia? Rethinking legal constraints on the detention of non-citizens. University of New South Wales Law Journal 38(4): 1386–1420.

Billings P (2019) Regulating crimmigrants through the ‘character test’: Exploring the consequences of mandatory visa cancellation for the fundamental rights of non-citizens in Australia. Crime, Law and Social Change 71(1): 1–23.

Boon-Kuo L (2017) Policing Undocumented Migrants: Law, Violence and Responsibility. New York: Routledge.

Bosworth M (2017) Penal humanitarianism? Sovereign power in an era of mass migration. New Criminal Law Review 20(1): 39–65. https://doi.org/10.1525/nclr.2017.20.1.39

Davey M (2015) Border Force confirms asylum seeker dead after setting himself on fire. The Guardian, 20 October. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2015/oct/20/border-force-confirms-asylum-seeker-dead-after-setting-himself-on-fire

Department of Home Affairs (2019) Illegal Maritime Arrivals on Bridging E Visa. 30 June. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/research-and-stats/files/illegal-maritime-arrivals-bve-june-2019.pdf

Department of Immigration and Border Protection (2013) Code of Behaviour for Subclass 050 Bridging (General) Visa Holders.

Department of Immigration and Border Protection (2014) Department of Immigration and Border Protection SRSS Contracts with Adult Multicultural Education Services and Australian Red Cross. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/foi/files/2017/FA170600046-documents-released.pdf

Department of Immigration and Border Protection (2015) Annual Report 2014–15. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/Annualreports/dibp-annual-report-2014-15.pdf

Department of Immigration and Border Protection (2016a) Annual Report 2015–16. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/ReportsandPublications/Documents/annual-reports/annual-report-full-2015-16.pdf

Department of Immigration and Border Protection (2016b) Documents Released under Freedom of Information Request by Anthea Vogl and Elyse Methven Dated 18 February 2016. 6 December.

Explanatory Statement (2013) Migration Amendment (Bridging Visas—Code of Behaviour) Regulation 2013 (Cth). https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/F2013L02102/Explanatory%20Statement/Text

Fleay C and Hartley L (2016) ‘I feel like a beggar’: Asylum seekers living in the Australian community without the right to work. Journal of International Migration and Integration 17(4): 1031–1048. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-015-0453-x

Gerard A and Weber L (2019) ‘Humanitarian borderwork’: Identifying tensions between humanitarianism and securitization for government-contracted NGOs working with adult and unaccompanied minor asylum seekers in Australia. Theoretical Criminology 23(2): 266–285. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362480618819814

Giannacopoulos M (2017) Migratory Austerity: Colonial Law’s Slow Violence. https://acrawsa.org.au/2017/12/28/migratory-austerity-colonial-laws-slow-violence/

Giannacopoulos M and Loughnan C (2019) When closure isn’t closure: Carceral expansion on Manus Island. 17 July. The Comparative Network on Refugee Externalisation Policies. https://arts.unimelb.edu.au/school-of-social-and-political-sciences/research/comparative-network-on-refugee-externalisation-policies/blog/carceral-expansion

Grewcock M (2011) Punishment, deportation and parole: The detention and removal of former prisoners under section 501 Migration Act 1958. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology 44(1): 56–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004865810392866

Hartley L and Fleay C (2017) ‘We are like animals’: Negotiating dehumanising experiences of asylum-seeker policies in the Australian community. Refugee Survey Quarterly 36(4): 45–63. https://doi.org/10.1093/rsq/hdx010

Hekmat AK (2018) Asylum seekers’ benefits cut by Home Affairs. The Saturday Paper, 14 April. https://www.thesaturdaypaper.com.au/news/politics/2018/04/14/asylum-seekers-benefits-cut-home-affairs/15236280006087

Keany F (2016) Peter Dutton criticises advocates after refugees set themselves on fire on Nauru. ABC News, 3 May. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-05-03/peter-dutton-says-refugees-encouraged-by-advocates-nauru/7378938

Markus A and Taylor J (2006) No work, no income, no Medicare—the Bridging Visa E regime. People and Place 14(1): 43.

McNevin A and Correa-Velez I (2006) Asylum seekers living in the community on Bridging Visa E: Community sector’s response to detrimental policies. Australian Journal of Social Issues. https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/handle/1885/18213

Methven E (2017) Dirty Talk: A Critical Discourse Analysis of Offensive Language Crimes. Sydney: University of Technology Sydney.

Morrison S (2013) Operation Sovereign Borders Update—Australian Border Force Newsroom. Press Conference. https://newsroom.abf.gov.au/releases/transcript-press-conference-operation-sovereign-borders-update-9

Neave C (2016) The Administration of People Who Have Had Their Bridging Visa Cancelled Due to Criminal Charges or Convictions and are Held in Immigration Detention. December. Commonwealth Ombudsman. http://www.ombudsman.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0026/42596/December-2016_Own-motion-investigation-into-people-who-have-their-Bridging-visa-cancelled-following-criminal-charges.pdf

Nettleback A and Ryan L (2018) Salutary lessons: Native police and the ‘civilising’ role of legalised violence in colonial Australia. The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 46(1): 47–68.

Randolph M, Vogl A, Methven E and Weber L (2019) Australia’s Asylum Seeker Code of Behaviour: A Statistical Analysis, Border Crossing Observatory Research Brief No. 15. https://www.monash.edu/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/1872061/research-brief-15-FINAL-MR.pdf

Ray Hadley Show (2013) Interview between Ray Hadley and Scott Morrison. Sydney, Australia: 2GB. http://www.2gb.com/audioplayer/7536#.U4QmkH95dy0

Refugee Council of Australia (2018a) Australia’s asylum policies. https://www.refugeecouncil.org.au/asylum-policies/

Refugee Council of Australia (2018b) Starving Them Out: How Our Government is Making People Seeking Asylum Destitute. 26 March. https://www.refugeecouncil.org.au/getfacts/seekingsafety/starving-them-out/

Simon J (1995) Ballad of a thin man: Sociolegal studies in a time of postmodern crisis. Law & Society Review 29(4): 631–638. https://doi.org/10.2307/3053916

Steel Z, Silove D, Brooks R, Momartin S, Alzuhairi B and Susljik I (2006) Impact of immigration detention and temporary protection on the mental health of refugees. The British Journal of Psychiatry 188(1): 58–64. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.104.007864

Stott R (2015) A refugee committed suicide at Brisbane airport and barely anyone noticed. BuzzFeed, 2 November. https://www.buzzfeed.com/robstott/a-refugees-public-suicide-and-the-system-that-let-him-down

Stumpf J (2006) The crimmigration crisis: Immigrants, crime, and sovereign power. American University Law Review 56: 367–420.

Tofighian O (2020) Introducing Manus prison theory: Knowing border violence. Globalizations 17(7): 1138-1156. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2020.1713547

Tribunal Member Kay Ransome (2015) Applicant name suppressed.

Vogl A (2019) Crimmigration and refugees: Bridging visas, criminal cancellations and ‘living in the community’ as punishment and deterrence. In Billings P (ed) Crimmigration in Australia: Law, Politics, and Society. Singapore: Springer: 149–171.

Vogl A and Methven E (2015) We will decide who comes to this country, and how they behave: A critical reading of the asylum seeker Code of Behaviour. Alternative Law Journal 40(3): 175–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/1037969x1504000307

Weber L (2013) Policing Non-Citizens. London: Routledge.

Weber L (2019a) From state-centric to transversal borders: Resisting the ‘structurally embedded border’ in Australia. Theoretical Criminology 23(2): 228–246.

Weber L (2019b) Resisting the ‘structurally embedded border’ in Australia. Border Criminologies. https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2019/05/resisting

Weber L and Pickering S (2014) Constructing voluntarism: Technologies of ‘intent management’ in Australian border controls. In Schwenken H and Ruß-Sattar S (eds) New Border and Citizenship Politics: 17–29. Migration, Diasporas and Citizenship Series. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137326638_2

Zedner L (2010) Security, the state, and the citizen: The changing architecture of crime control. New Criminal Law Review; Berkeley 13(2): 379–403. http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.lib.uts.edu.au/10.1525/nclr.2010.13.2.379

Explanatory Statement, Migration Amendment (Subclass 050 and Subclass 051 Visas) Regulation 2013 (Cth) (n.d.).

Migration Act 1958 (Cth)

Migration Amendment (Bridging Visas - Code of Behaviour Regulation 2013 (Cth)

[1] This discrepancy is because these numbers also include re-grants of a visa to the same applicant due to the short-term nature of BVEs. Thus, of this figure, around 4005 were initial BVE grants and 53,426 were BVE re-grants (Department of Immigration and Border Protection 2016b: 1).

[2] This number is recorded as at 30 June 2019. The fall in numbers is a result of BVEs receiving a substantive visa, being returned to immigration detention, departing Australia or having since deceased (Department of Home Affairs 2019).

[3] Medicare is Australia’s government-funded health insurance system, which provides access to core health and hospital services at low or no cost.

[4] Markus and Taylor also note the complexity of how and when conditions attach, making the visa class itself a strategy, with the complexity further marginalising BVE holders (Markus and Taylor 2006).

[5] When the Code was introduced, the Department labelled asylum seekers arriving by boat ‘Illegal Maritime Arrivals’ or IMAs. The term used in the legislation is ‘Unauthorised Maritime Arrivals’ or UMAs; however, the Government often uses the two designations interchangeably.

[6] This FOI request followed a previous request covering the same information but for the period from the Code’s commencement to mid-2014. For details of the limited use of the Code in this period, see Vogl and Methven (2015).

[7] For statistical and graphic representations of the data, see Randolf et al. (2019).

[8] In 18 instances, no breach was found (4%), and in 66 instances (13%) the assessor decision was ‘insufficient evidence’. In 68 instances (14%), no assessor decision was recorded. The discrepancy in numbers reflects the fact that in some instances there was a BVE cancellation or non-renewal even though no breach was recorded, and so these are double counted for the purposes of outcomes.

[9] The nature of the caseworker is not explained and could refer to an SRSS provider or another kind of worker.

[10] The Migration Review Tribunal was the former Australian Administrative Tribunal that reviewed migration decisions. In 2015, the Tribunal was dismantled and merged with the Administrative Appeals Tribunal, with decisions now made under its Migration and Refugee Division.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/IntJlCrimJustSocDem/2020/49.html