|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy |

How Women’s Police Stations Empower Women, Widen Access to Justice and Prevent Gender Violence

Queensland University of Technology, Australia

Natacha Guala

Universidad Nacional del Litoral, Argentina

María Victoria Puyol

Queensland University of Technology, Australia

Máximo Sozzo

Universidad Nacional del Litoral, Argentina

|

Abstract

Women’s police stations are a distinctive innovation that emerged in

postcolonial nations of the global south in the second

half of the twentieth

century to address violence against women. This article presents the results of

a world-first study of the

unique way that these stations, called

Comisaría de la Mujer, prevent gender-based violence in the

Province of Buenos Aires,

Argentina.[1] One in five police

stations in this Province was established with a mandate of preventing gender

violence. Little is currently known

about how this distinctive multidisciplinary

model of policing (which includes social workers, lawyers, psychologists and

police)

widens access to justice to prevent gender violence. This article

compares the model’s virtues and limitations to traditional

policing

models. We conclude that specialised women’s police stations in the

postcolonial societies of the global south increase

access to justice, empower

women to liberate themselves from the subjection of domestic violence and

prevent gender violence by challenging

patriarchal norms that sustain it. As a

by-product, these women’s police stations also offer women in the global

south a career

in law enforcement—one that is based on a gender

perspective. The study is framed by southern criminology, which reverses the

notion that ideas, policies and theories can only travel from the anglophone

world of the global north to the global south.

Keywords

Gender-based violence; women’s police stations; violence prevention;

southern criminology; women in policing.

|

This article draws from the results of a world-first study into women’s police stations in Argentina as presented at the 63rd Commission on the Status of Women NGO sessions in New York, in March 2019. First, we outline the background of women’s police stations in the postcolonial societies of the global south, designed to explicitly respond to and prevent gender-based violence. These stations are distinguished from the female-only police units that existed in the global north, which restricted women in law enforcement to caring for females and children in custody. The main substance of the article presents the results of our empirical study on the role of women’s police stations in preventing gender violence in the Province of Buenos Aires, Argentina. The Province established its first women’s police station in 1988 and by the end of 2018 had 128 stations and another 16 specialist units. These stations account for one in five of all police stations in the Province and, since 2009, have had a legislated mandate to prevent gender violence, under the National Law to Prevent, Punish and Eradicate Violence against Women (Law No. 26485).[2] The final section of this article critically reflects on the virtues and limits of women’s police stations as a model for addressing and preventing gender-based violence. It concludes by comparing traditional policing to specialist policing approaches regarding the prevention of gender-based violence. The study is funded by the Australian Research Council and includes a multi-country team of researchers, whose contributions we gratefully acknowledge.[3]

Police stations responding specifically to violence against women are a distinctive innovation that emerged in postcolonial nations of the global south in the second half of the twentieth century (Natarajan 2008). It is important to first distinguish these stations from the sex-segregated female police units that emerged alongside all-male police units to oversee the arrest, charging and custody of women and children (Cartron 2015; Natarjan 2008). These gender-segregated police models that emerged across the global north reflected patriarchal norms that restricted female police to managing women and children. Policing was otherwise considered a masculine occupation (Prenzler and Sinclair 2013). For example, in England, women were employed in the metropolitan police in the early 1900s not as police, but as ‘matrons’ to oversee women and children in custody (Cartron 2015: 9). When women entered the police service in Australia, the United Kingdom (UK) and the United States (US) during or after WWII, they were assigned to sex-segregated units to care for women and children, or they were hired as assistants to male officers and detectives (Natarjan 2008: xiv; Prenzler and Sinclair 2013).

The first specialist police stations designed to respond specifically to violence against women emerged in Latin America in São Paulo, Brazil, in 1985 (Jubb et al. 2010). Variations of the model have since spread across other parts of the global south—in Bolivia, Ecuador, Nicaragua, Peru, Uruguay and, more recently, in Sierra Leone, India, Ghana, Kosovo, Liberia, the Philippines, South Africa and Uganda (Jubb et al. 2010). However, the existing body of research on this topic has focused mainly on women’s police units in India (Amaral et al. 2018; Natarajan 2008) and women’s police stations (Delegacia da Mulher [DDM]) in Brazil (Hautzinger 2002; Jubb et al. 2010; Perova and Reynolds 2017; Santos 2004: 50).

Women’s police stations designed to receive victims of male violence first emerged in Latin America in the 1980s, during a period of re-democratisation after the fall of brutal military dictatorships. In Spanish and Portuguese, these stations are called ‘police stations for women’, but for the sake of ease in this article, we call them women’s police stations.[4] In 1985, the state of São Paulo, Brazil, established its first DDM. By 2010, Brazil had established around 475 of these specialist police stations for women (Jubb et al. 2010). Significantly, the DDMs arose from a democratic process established by the newly elected governor, Franco Montoro, in a post-authoritarian Brazil. He established the State Council on Feminine Condition in 1983, which was staffed by women, including feminists and activists (Santos 2004: 35). This council followed the principles of participatory democracy by including actors from social movements in new hybrid state/society partnerships to address social problems that affect women. Most notably, SOS-Muhler (SOS women)—an activist group that had campaigned for the victims of domestic and sexual violence since the early 1980s—welcomed the proposal to establish women’s police stations (Santos 2004: 36). This was despite feminist qualms regarding collaboration with the coercive arm of the state to enact effective interventions to end violence against women (Nelson 1996).

The Emergence of Women’s Police Stations in Argentina

On 6 March 1947, Elena Corporate de Mercante, the spouse of the Governor of La Plata, accompanied by the Head of the Police, announced the first female brigade (Brigada Femenina) in Argentina and, indeed, in all of Latin America (Calandrón and Galeano 2013: 176). The first female police in Argentina were assigned to work in the female detachment units in the cities of La Plata and Mar del Plata, in the Province of Buenos Aires. These female police units functioned as a form of ‘surveillance of women accused of minor crimes and contraventions’ (Calandrón and Galeano 2013: 178).

The first women’s police station that was explicitly designed to respond to violence against women was established in La Plata in 1988, with three main rationalities underpinning its establishment. First, the station was thought to re-legitimise the reputation of the Buenos Aires Police Department (Policia de la Provincia de Buenos Aires), given the department’s brutal participation in state terrorism during the military dictatorship (e.g., kidnapping, raping, torturing, murdering young women) (Calandrón 2008). Second, the United Nations was becoming increasingly influential during this post-dictatorship period, securing peace in Latin America. The democratic Argentinian state subscribed to several United Nations international conventions during the 1980s, including ratifying in 1985 the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women. Women’s police stations were established, in part, as an institutional response to demonstrate Argentina’s commitment to women’s rights, as established under United Nations conventions (Calandrón 2014; Luppi 2017). Third, women’s police stations were created in response to the demands of feminist movements for the state to protect women from men’s violence. In 1987, the governor of Buenos Aires Province, Antonio Cafiero (1987–1991), established the Provincial Council for Women to advise the government on gender equality policies (Calandrón 2014). The Council implemented a program to prevent family and domestic violence and to raise community awareness of women’s rights. In 1990, through Decree 4570/90, the governor ratified an agreement between the Provincial Council for Women and the Ministry of Government,[5] initiating the gradual creation of women’s police stations across the Province (Calandrón 2014; Luppi 2017).

The number of women’s police stations in the Province initially grew slowly—with only 37 established over a 22-year period between 1988 and 2010. Between 2000 and 2009, there were three significant pieces of government legislation that led to the proliferation of women’s police stations: the 2001 provincial Law 12569 on family violence, the provincial Decree 3435 in 2004 that created the Directorate of Gender Policy within the Buenos Aires Police Department, and a national law in 2009 to prevent, punish and eradicate violence against women (Calandrón 2014; Duarte 2017; Pereiro 2014). An additional 91 women’s police stations were established to implement the National Action Plan. By the end of 2018, the Province of Buenos Aires had 128 specialist police stations, 16 specialist units, and 2300 officers who, in that year, responded to approximately 257,000 complaints of domestic violence and 7000 complaints of sexual assault (Directorate of Gender Policy, Ministry of Security 2019).

The structure of policing in Argentina differs significantly from that in countries like Australia, the UK or US. Rather than operating as a single, unified police service reporting to one commissioner, there are 12 commissioners who oversee the hierarchal command structure of distinctly different police units. These include units for road safety, accident safety, rural safety, police planning and operations, gender policy, judicial investigation, drug trafficking investigations and illicit crime organisation, scientific police, criminal intelligence, communications, social services and local crime prevention, and general secretary of police (Superindendencia General de Policía http://www.policia.mseg.gba.gov.ar/estructura.html). The Province has two different types of police stations that offer the public an emergency response: the general police (Comisaría) and police stations for women (Comisaría de la Mujer [CMF]). There are 645 stations in the Province, of which 517 are general police stations and the remaining 128 women’s police stations.[6] This means one in five police stations in the Province are specifically designed to respond to and prevent gender violence. Their sub-commanders (who are mostly women) report to the Superintendent of Gender Policy, which provides a career structure for female officers in law enforcement. Although most officers are female, male officers can and do work in women’s police stations in multidisciplinary teams of social workers, lawyers, police and psychologists.

Theoretical Framework and Method: Our Study of Women’s Police Stations in Argentina

Violence against women is a global policy issue with significant social, economic and personal consequences (World Health Organization 2013). Primary prevention is regarded as the key to preventing lethal gender-based violence (United Nations 2016). However, knowledge about violence prevention remains elusive, and what knowledge does exist has been based mainly on studies from anglophone countries of the global north (Arango et al. 2014: 1). Framed by southern criminology, which aims to redress such biases in the global hierarchy of knowledge (Carrington et al. 2016), our project reverses the notion that policy transfer should flow from the anglophone countries of the global north to the global south (Connell 2007). Our project aimed to discover, first, how women’s police stations—a unique invention of the global south—respond to and prevent gender-based violence and, second, what aspects could inform new approaches to responding and preventing gender-based violence elsewhere in the world. This article only reports on the first stage of the project, as the second stage is still in progress. In addition to ethics approval from QUT, our research team sought and was granted permission to undertake this study from the Superintendent of Gender Policy, Ministry of Security (Comisaría Directora General, Ministerio de Seguridad de la Provincia de Buenos Aires). It took three years and several face-to-face visits with the research team to secure this permission.

The study used a triangulated methodology that involved semi-structured interviews, field research, policy analysis and observations of community prevention work. We undertook semi-structured interviews with 100 staff—including police officers, social workers, lawyers and psychologists—from a stratified sample of 10 women’s police stations in the Province of Buenos Aires. Two of the stations, located at Tigre and Ezeiza, are situated relatively closely to the autonomous district and federal capital of Buenos Aires. Another three were in La Plata, the capital of the Buenos Aires Province, with one in the city centre and another two in Berisso and Ensenada, municipalities of the Greater La Plata city. The other five stations—Azul, Bahia Blanca, Mar del Plata, Olvarria and Tandil—span a radius of approximately 2500 km across the coastal and rural regions of the Province. We have referred to these stations as A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I and J to protect the anonymity of our respondents. Importantly, the specialist police stations were purposively selected by the Directorate of the Co-ordination of CMFs to reflect the diversity of their operations. The field research and interviews were undertaken over three months in October and November of 2018 and in March of 2019. All stations had been in operation for at least six years, the longest one for 30 years. All interviews were recorded in Spanish, and transcripts quoted in this article have been translated by the ARC research team.

The interview instrument was divided into six sections. The first asked standard questions about socio-demographic background, while the second asked questions about the length of time worked in a CMF and about any specific training undertaken with respect to the job. The third block asked questions about how the policewomen engaged with the community and the types of public outreach that they undertook, as well as about the preventative aspects of their work. The fourth block of questions related to typical profiles of victims seeking their assistance. The fifth set of questions concerned the general operating protocols of the station, and any significant changes to these protocols. The last block of questions related mainly to the influence of the women’s movements demanding that the Argentinian state do more to protect women from femicide and domestic and sexual violence.

The interview data were triangulated with field research notes, data from public policies, web sites and, in some cases, photos and videos of activities between the CMF and the public. The directors of each CMF voluntarily provided this additional information. The field research also included guided tours of the stations, participation in community prevention activities alongside policewomen and observations as passengers in policewomen’s cars. Notebooks of the time, activity, participants and any other relevant observations were kept throughout the field research. Due to space constraints, we principally draw on the research team’s photos that were taken during the field work as a means of contextualising and enriching our interview data.

Discussion of Results

This is the first study of its kind in Argentina and one of the very few in the world to interview the multidisciplinary employees of specialist police stations that were designed to respond only to domestic, sexual and family violence. Most of the interviewees were female (89 per cent), 79 per cent were employed as police and 21 per cent worked as lawyers, psychologists or social workers (see Table 1). Most (73 per cent) were aged between 26 and 45 years of age (see Table 4). The median length of service in a women’s police station was six to eight years, with the longest being 30 years (see Table 12 in Carrington et al. 2019). Seventy per cent of interviewees had professional qualifications in public security—which is the same training undertaken by the common police (see Table 2). The remaining interviewees had qualifications in law, social work and psychology (see Table 3). Most (73 per cent) had specialist training for working in women’s police stations, and 78 per cent considered the training useful or very useful (see Table 3). Given the breadth of these interviewees’ collective experience, the cohort was well qualified and informed to answer our questions.

Table 1: Interviews by Sex and Profession, Women’s Police Stations Buenos Aries Province

|

Female

|

Male

|

Total

|

Police

Officer

|

Lawyer

Psychologist

Social Worker

|

|

|

A

|

12

|

1

|

13

|

12

|

1

|

|

B

|

8

|

1

|

9

|

7

|

2

|

|

C

|

11

|

0

|

11

|

10

|

1

|

|

D

|

8

|

2

|

10

|

9

|

1

|

|

E

|

7

|

1

|

8

|

6

|

2

|

|

F

|

10

|

2

|

12

|

10

|

2

|

|

G

|

10

|

2

|

12

|

10

|

2

|

|

H

|

8

|

1

|

9

|

7

|

2

|

|

I

|

7

|

1

|

8

|

6

|

2

|

|

J

|

8

|

0

|

8

|

4

|

4

|

|

Total

|

89

|

11

|

100

|

81

|

19

|

Table 2: Professional Qualifications

|

Public Security

Police Training

|

Social Work

|

Law

|

Psychology

|

Other

|

Total

|

|

|

A

|

9

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

3

|

13

|

|

B

|

7

|

0

|

1

|

1

|

0

|

9

|

|

C

|

6

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

4

|

11

|

|

D

|

7

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

2

|

10

|

|

E

|

6

|

1

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

8

|

|

F

|

9

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

0

|

12

|

|

G

|

9

|

1

|

1

|

0

|

1

|

12

|

|

H

|

7

|

1

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

9

|

|

I

|

6

|

0

|

1

|

1

|

0

|

8

|

|

J

|

4

|

1

|

1

|

2

|

0

|

8

|

|

Total

|

70

|

6

|

7

|

7

|

10

|

100

|

Table 3: Specialist Training to Work in Women’s Police Stations

|

Have you received specialist training to work in a women’s police

station?

|

Was it useful?

|

|

||||||

|

Station

|

Yes

|

No

|

No Answer

|

Very

|

Some

what

|

No

|

No

Answer

|

Total

|

|

A

|

10

|

3

|

0

|

5

|

4

|

2

|

2

|

13

|

|

B

|

9

|

0

|

0

|

6

|

0

|

0

|

3

|

9

|

|

C

|

7

|

4

|

0

|

6

|

5

|

0

|

0

|

11

|

|

D

|

6

|

2

|

2

|

6

|

4

|

2

|

2

|

10

|

|

E

|

4

|

4

|

0

|

1

|

3

|

0

|

0

|

8

|

|

F

|

8

|

2

|

2

|

2

|

7

|

1

|

2

|

12

|

|

G

|

10

|

0

|

2

|

9

|

1

|

0

|

2

|

12

|

|

H

|

7

|

2

|

0

|

4

|

3

|

0

|

2

|

9

|

|

I

|

7

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

7

|

1

|

0

|

8

|

|

J

|

5

|

3

|

0

|

3

|

2

|

0

|

3

|

8

|

|

Total

|

73

|

21

|

6

|

42

|

36

|

6

|

16

|

100

|

Table 4: Age of Interviewees

|

Station

|

Age

|

|||||

|

|

18-25

|

26-35

|

36-45

|

46-55

|

56-65

|

Total

|

|

A

|

0

|

8

|

4

|

0

|

1

|

13

|

|

B

|

0

|

3

|

3

|

2

|

1

|

9

|

|

C

|

0

|

5

|

2

|

3

|

1

|

11

|

|

D

|

1

|

4

|

3

|

2

|

0

|

10

|

|

E

|

1

|

1

|

4

|

1

|

1

|

8

|

|

F

|

1

|

5

|

4

|

1

|

1

|

12

|

|

G

|

0

|

4

|

4

|

4

|

0

|

12

|

|

H

|

5

|

1

|

2

|

0

|

1

|

9

|

|

I

|

0

|

5

|

3

|

0

|

0

|

8

|

|

J

|

0

|

3

|

5

|

0

|

0

|

8

|

|

Total

|

8

|

39

|

34

|

13

|

6

|

100

|

Working in a Women’s Police Station

This section provides an overview of what it is like to work in a women’s police station in the Province, based on our field work, observations and interviews with the multidisciplinary teams who work with victims of gender violence and their families. When compared to traditional policing models, these specialist police stations display some similarities, but also distinctive differences, in appearance, protocols, policies and methods of responding to and preventing gender violence. Like traditional policing models, women’s police stations provide an emergency response, as they operate 24 hours a day, every day of the year. One police officer commented,

‘We work at 100 per cent ... The police station operates 24 hours a day, 365 days a year ... Here the door does not close, the computer does not turn off’ (Police Officer, Station B).

One distinguishing feature is that the police collaborate in multi-professional teams with lawyers, social workers and psychologists in the same premises. Interdisciplinary teams act as a gateway for integrated services in policing, legal support, counselling, and housing and financial advice to help address the multidimensional problems that survivors of domestic and sexual violence typically experience. Importantly, access to support does not depend on whether victims decide to formally report or pursue a criminal conviction. It is thus not surprising that 71 per cent of interviewees described their role as working with victims to provide access to justice, and that 70 per cent said that it was to provide information about gender violence (see Table 5). Just over half of the interviewees (56 per cent) said that they provided assistance to victims in regard to leaving a violent relationship (see Table 5).

Table 5: Routine Roles of Employees at Women’s Police Stations

|

|

Which one of the following best describes your role at the Women’s

Police Station?

|

||||||||

|

Station

|

Prevention action in the community

|

Working with victims

|

Receive complaints

|

Investigate

complaints

|

Child care

|

Provide victims access to justice

|

Assist victims to leave violent partner

|

Provide information on gender violence

|

Raise complaints with other agencies

|

|

A

|

9

|

8

|

11

|

6

|

9

|

9

|

7

|

8

|

4

|

|

B

|

9

|

9

|

7

|

7

|

7

|

8

|

3

|

7

|

7

|

|

C

|

6

|

9

|

6

|

2

|

5

|

7

|

7

|

6

|

6

|

|

D

|

8

|

8

|

4

|

6

|

6

|

6

|

4

|

6

|

4

|

|

E

|

4

|

7

|

3

|

7

|

3

|

7

|

7

|

7

|

7

|

|

F

|

6

|

6

|

4

|

0

|

4

|

6

|

4

|

6

|

4

|

|

G

|

7

|

7

|

5

|

5

|

6

|

9

|

7

|

9

|

5

|

|

H

|

7

|

9

|

7

|

5

|

5

|

7

|

6

|

9

|

2

|

|

I

|

7

|

4

|

6

|

0

|

6

|

6

|

7

|

6

|

7

|

|

J

|

4

|

4

|

2

|

0

|

4

|

6

|

4

|

6

|

2

|

|

Total

|

67

|

71

|

55

|

38

|

55

|

71

|

56

|

70

|

48

|

Note: Respondents were able to select more than one answer

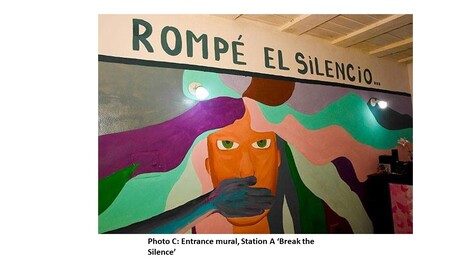

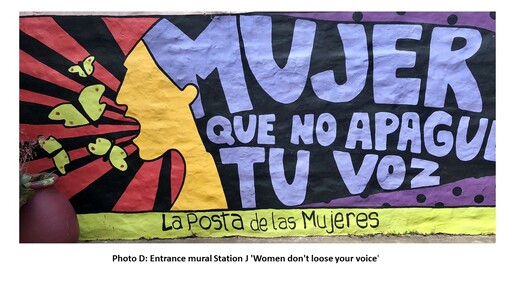

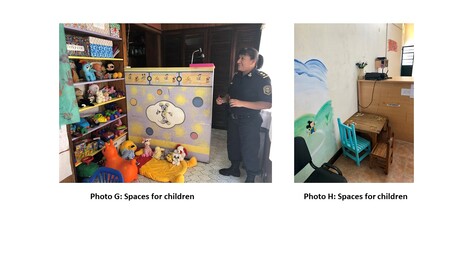

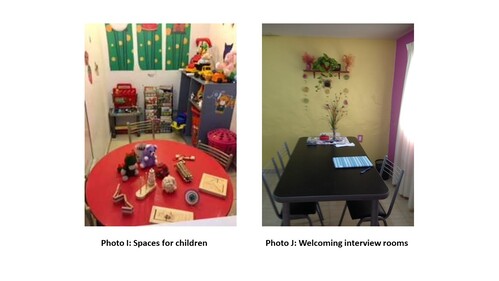

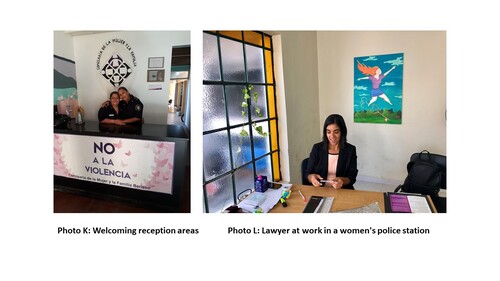

CMFs differ significantly in their appearance to general police stations. Seven of the 10 CMFs in which we conducted interviews resembled brightly painted houses in residential streets (usually purple, yellow, sky blue, pink or green) and had welcoming reception rooms, play rooms or spaces for children and inviting interview rooms adorned with flowers and murals (see Photos A–L, all photos courtesy of author/s). The other three occupied offices or shopfronts in city centres. These specialist stations are deliberately designed to receive victims, not offenders, and they do not have holding cells, making them significantly less costly. The distinctive appearances of their stations’ patrol cars and buildings are also deliberately designed to encourage visibility and enhance reporting. One of the psychologists interviewed described their location among the community as, ‘a strategic area where women come ... After so much time we’ve built a bond of fellowship ... And that is good ... That’s why it’s strategic, because people come’ (Psychologist, Station B).

Women can come at any time of the day or night with their children (see Photos G–I). When women arrive with nothing, they can access emergency provisions of clothing, food and support, much of it donated by the local community or station employees. Of those interviewed, 55 per cent said that their routine work included childcare duties (see Table 5), which distinguishes them from general police. Interviewees considered the provision of a space for children critical for encouraging women to come to the station and seek help:

For children, it is very important to have their own space, separate from where the mother is explaining what happened, not to relive everything ... It seems frivolous, but having a television while people wait, a space for the children ... The women have to come with their children and have nowhere to leave them. We try to make it a different space, with colours, with games. (Police Officer, Station B)

CMFs have their own hierarchy of command within the Ministry of Security. During the last decade, the commissioner of the CMFs has risen in the ranks of the ministry and, since 2015, is now equal to all other 12 commissioners. By having their own hierarchal command structure, the CMF offers a unique career structure that is not available to women who are integrated in traditional policing models in Argentina, nor indeed elsewhere (Carrington et al. 2019; Natarajan 2008: 18; Prenzler and Sinclair 2013). As elsewhere in Latin America, women’s police stations opened a new job market for women and improved the promotion prospects of women in policing (Hautzinger 2002; MacDowell Santos 2004). Regardless of gender, police officers can transfer from the general police to the specialist police for women as part of a chosen career path in law enforcement. However, it is primarily women in the Province who choose this career pathway, as evidenced by our representative sample (see Table 3). Nine of the 10 commanders and 89 per cent of the police we interviewed were female. The sole male commander among our cohort had previously worked in the general police for 12–14 years and had been transferred to act as the temporary commander of Station D. He also described himself as ‘working from a gender perspective’, that understands most violence against women occurs in a context of gendered power relations and coercive control.

In contrast to traditional policing, prevention work is obligatory and thus essential to the work of women’s police stations in the Province of Buenos Aires. Almost 71 per cent of those interviewed described prevention as being a part of their role at the women’s police station (see Table 5). When we asked what kind of prevention activities they undertook, we discovered that prevention assumed many forms, but that it can be divided into three principal strategies. The first is working with women and their families (including perpetrators) to prevent re-victimisation, to increase access to justice and to denaturalise violence and empower women. The second is partnering with the community to prevent violence by collectively transforming the cultures and norms that sustain violence against women. The third is working collaboratively with other organisations to create a local road map for preventing gender violence. Below, we describe in more detail how women’s police stations engage in these three different approaches to prevent gender violence.

Working with Victims, Families and Perpetrators to Unlearn and Denaturalise Gender Violence

Women’s police stations have historically only received complaints of domestic and sexual violence from women. This model is based on an outdated heteronormative assumption that only women can be victims and men perpetrators, and on the essentialist assumption that women will be more empathetic to victims simply because of their gender (Hautzinger 2002: 246). The employees we interviewed reported that this view is changing, as male, female and LGBTQ victims can seek assistance. However, 74 per cent of our respondents said that the frequency that they received reports from LGBTQ victims was ‘very little’ (see Table 7; Carrington et al. 2019). Interestingly, some of the stations accept self-reports from men seeking help to curb their violence towards their partners. In such cases, the police can refer these men to support groups that have been established by the local authorities to ‘unlearn’ violent conduct:

There have been cases of men coming to ask for help, who recognise that the situation is overwhelming, and they come voluntarily to ask for help ... There is a group of men who work with men who exercise violence ... The program is called ‘unlearning’; the idea is to work in these reflection groups about their behaviours. (Psychologist, Station C)

Table 6: What types of violence are reported most frequently?

|

Station

|

Physical Violence

|

Psychological Violence

|

Sexual Abuse

|

Symbolic Violence

|

Economic Violence

|

Internet Abuse

|

|

A

|

13

|

7

|

4

|

3

|

9

|

8

|

|

B

|

9

|

9

|

0

|

9

|

7

|

7

|

|

C

|

11

|

11

|

1

|

7

|

7

|

4

|

|

D

|

6

|

4

|

2

|

0

|

4

|

0

|

|

E

|

8

|

7

|

4

|

3

|

4

|

0

|

|

F

|

12

|

12

|

4

|

0

|

8

|

0

|

|

G

|

12

|

12

|

12

|

4

|

6

|

2

|

|

H

|

9

|

9

|

8

|

3

|

5

|

4

|

|

I

|

8

|

8

|

7

|

0

|

3

|

0

|

|

J

|

8

|

6

|

8

|

0

|

8

|

0

|

|

Total

|

96

|

85

|

50

|

29

|

61

|

25

|

Physical and domestic violence was by far the most likely form of violence to which women’s police stations had to respond, though they also responded to complaints of sexual assault and abuse on the internet (see Table 6). One of the commanders interviewed stressed that the organisational aim of women’s police stations is to break the cycle of violence by empowering women through access to justice and other victim support services:

The goal is to break the circle of violence, It’s a whole process, often the victim returns ... But, she does not have to believe that an insult or aggression is normal because she suffers it for 10 years. This police station provides this information ... that nobody should hit you or insult you, that you have to be respected. (Commander, Station C)

Another police officer interviewed described prevention with victims as being a process of ‘denaturalising’ domestic violence, of working with women to help them escape a violent partner. In fact, over half of those interviewed (56 per cent) described that helping women leave a violent relationship was a part of their role (see Table 5):

For me, the goal is to reduce violence against women ... to aid to the person suffering violence and to try reduce the cases that end up as femicide. Prevention is the first step so that something more serious does not happen. (Police Officer, Station A)

Several of the police stations hosted women’s support groups and online chat groups—some more successfully than others, depending on resources. One of the psychologists who had convened a survivor support group for 11 years described how it operated this way:

The group of women has functioned since 2007. In principle, women are guided to recover their self-esteem and ability to decide ... Here, they lose the fear. Generally, about 15 women come weekly. Then we have a follow-up [online] chat group. We are in permanent contact. The group of women helps them not to feel alone, to sustain the decision to report or get away. (Psychologist, Station B)

The women’s support groups that are facilitated by women’s police stations are reflective spaces in which participants can overcome complex and ambiguous emotions of guilt and shame. The psychologists we interviewed participated as coaches in these groups, with most of the conversation led by survivors. This type of linguistic exchange allows women in the group to exercise agency and power in the conversational exchange (Ostermann 2003). By creating a positive community of practice, the groups support victims to become survivors and to break the cycle of violence—what one psychologist termed as the oppression of ‘subjection’. The objective of working with women’s groups is to raise awareness, empower women and build resilience so that re-victimisation is prevented. Strategies of empowerment are practical and include providing victims with emergency supplies, access to other justice services and access to psychological and legal support, as in Brazil’s specialist police stations (Ostermann 2003: 477). Coaching women to regard themselves differently—and thus their situation as not being an ongoing inevitable submission—also empowers victims to break the cycle of violence, and liberate herself from that subjection, as this psychologist explains.

Sometimes with an interview you can do much more than you think. Making a woman listen, can generate some change, a movement. In that sense, I do believe that it can prevent violence ... That’s the objective. It is an active listening so that the woman can separate from that relationship of submission... so that she can be strengthened. (Psychologist, Station C)

In a study of policing in Pacific Island states, Bull et al. (2017: 9) argued that women police are both insiders and outsiders, who ‘may be perceived as having a particular effectiveness or objectivity that is valuable in the regulation ... most particularly, (of) crimes of gendered violence’. They argued that women police are insiders because they belong to the same gender, and this link enhances other women’s willingness to confide in them. However, as outsiders with state power to enforce laws that criminalise gender violence, women police are situated in the unique position of being able to challenge local norms that underpin gender violence and taking action against perpetrators. Upon reflection, these insights can be more broadly applied to an analysis of women’s police stations. It is the unique formal and informal regulatory framework of women’s police stations that enhances their capability to respond and prevent gender violence in new and novel ways. One such way is how they embed themselves into the community, which we will now discuss.

Working with Communities to Prevent Gender Violence

In the Province of Buenos Aires, women’s police stations are also mandated under the National Action Plan to undertake community prevention activities at least once a month. The stations engage with numerous communities and organisations in their prevention work to fulfil this obligation, such as with religious organisations, women’s groups, schools, hospitals, and neighbourhood and community groups (see Table 7). When asked what kind of prevention activities they undertook with the community, 56 per cent of interviewees replied that they worked with schools and 65 per cent that they worked with local neighbourhood or community groups (see Table 7).

Table 7: Working with communities to prevent gender violence

|

What other organisations do you work with to reduce the impact of gender

violence in your community?

|

||||||

|

Station

|

Religious

|

Women's

Groups

|

Schools

|

Neighbourhood

or Community

Groups

|

Hospitals

|

Other

|

|

A

|

2

|

5

|

7

|

8

|

6

|

0

|

|

B

|

7

|

7

|

8

|

8

|

8

|

1

|

|

C

|

4

|

7

|

10

|

7

|

0

|

0

|

|

D

|

2

|

6

|

6

|

6

|

0

|

2

|

|

E

|

0

|

0

|

4

|

4

|

0

|

0

|

|

F

|

2

|

2

|

6

|

10

|

2

|

4

|

|

G

|

5

|

10

|

7

|

9

|

4

|

0

|

|

H

|

0

|

6

|

1

|

4

|

2

|

0

|

|

I

|

3

|

7

|

7

|

7

|

6

|

0

|

|

J

|

2

|

6

|

0

|

2

|

2

|

0

|

|

Total

|

27

|

56

|

56

|

65

|

30

|

7

|

The employees of women’s police stations organise community prevention campaigns around an annual program of festival and events, such as around days of protest against femicide (Ni una Menos, during June) and days to celebrate international women’s day (

Día Internacional de la Mujer, 8 March) and rights of the child (Le dia de los Ninos, the third Sunday of August) (see Photos M and N). In anticipation of an increasing rate of gender violence over Christmas, women’s police stations strategically distribute their contact details to hundreds of children and women by attaching this information to the wrapping of presents (see Photos O and P). In one station, the entire team dresses up as Santa and Santa’s helpers and drives through the local neighbourhood in their police cars with their sirens blaring. When children and parents pile into the streets in response, they are handed toys and lollies with the CMF’s contact details. They are also invited to a Christmas party at the women’s police station, which is part of a strategy to familiarise local women with their services and build trust and rapport. The commander of one station described their preventative work in glowing terms:

We like it a lot ... good days for prevention include the festival of the child and Christmas festivals, which we always repeat every year. We really like that interaction with the community ... This year, triple the amount of people came (to the Christmas party) ... [When] we travelled [the local barrio] ... as we passed... the people applauded us, [their photos and videos of] it went out in all the social networks ... Oh! Seeing the kids jumping when the police car arrived with Santa Claus ... it’s very exciting. Very, very rewarding. (Commander, Station A)

A zone commander with 30 years’ experience of working in CMFs summarised how community prevention overlaps with other strategies for prevention:

Prevention is aided by the proximity (of the women’s police stations) with the citizen, on the one hand, and by the relationship with the Local Board ... Now we have started working with violent men, with the Human Rights Secretariat, the Local Board, the Addiction Prevention Centre and the Board of Freemen. (Zone Commander)

The community prevention activities of women’s police stations in Argentina genuinely distinguish them from the women’s police in Brazil and India, who do not have a mandate under a national action plan to conduct primary prevention. Women’s police stations’ community policing activities are designed to raise awareness and build local networks and partnerships, to revert the outdated patriarchal norms in the community that continue to underpin and tolerate violence against women.

Working with Organisations to Prevent Gender Violence

While many police organisations in Australia and elsewhere in the world collaborate with other government organisations as part of their routine response to domestic and sexual violence complaints, women’s police stations are mandated under the 2009 National Action Plan to meet monthly. They collaborate with other government, local and provincial organisations through Mesas Locales (‘local boards’) that are strategically important for coordinating the localised activities of the many agencies involved in responding to and preventing gender violence. Mesas Locales gather representatives of state agencies in the health, education, judiciary, human rights, children and gender policy areas to coordinate local actions and strategies for responding to and preventing gender violence. Of those interviewed, 86 per cent worked with these local social development boards (see Table 8).

Table 8: Government Agencies that Work with Women’s Police Stations to Prevent Gender Violence

|

Which government agencies does this CMF work to reduce the impact of

gender violence in the community?

|

|||||||||||

|

Station

|

Local Social Development

|

Provincial Social Development

|

Gender Policy Units

|

Public Prosecutor's Office

|

Public Criminal Defence

|

Judicial Office/

Courts

|

Provincial Education Organisations

|

Women's Political Organisations

|

Access to Justice Centres

|

Justice of Peace

|

Ombudsman

|

|

A

|

6

|

0

|

10

|

6

|

4

|

3

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

10

|

6

|

|

B

|

9

|

2

|

9

|

7

|

3

|

9

|

2

|

0

|

2

|

0

|

4

|

|

C

|

10

|

5

|

11

|

10

|

9

|

9

|

5

|

5

|

4

|

0

|

1

|

|

D

|

6

|

4

|

4

|

6

|

0

|

4

|

0

|

2

|

0

|

0

|

4

|

|

E

|

7

|

0

|

7

|

7

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

4

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

F

|

12

|

0

|

12

|

12

|

0

|

12

|

2

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

G

|

11

|

0

|

12

|

11

|

6

|

12

|

0

|

0

|

4

|

0

|

0

|

|

H

|

9

|

0

|

9

|

9

|

9

|

9

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

I

|

8

|

0

|

5

|

8

|

7

|

8

|

0

|

0

|

4

|

0

|

0

|

|

J

|

8

|

2

|

8

|

8

|

4

|

7

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

Total

|

86

|

13

|

87

|

84

|

42

|

73

|

9

|

11

|

14

|

10

|

15

|

The following is a typical description of the importance of these institutional collaborations:

We work with the Local Board; we meet once a month and articulate with the municipal areas of social development, gender and education. We also work directly with the Gender Secretariat of one of the Prosecutor’s Offices that deals exclusively with acts of violence and with the Family Court. Luckily, in Station F, we have excellent relationships with these organisations. (Police Officer, Station F)

Over 87 per cent of those interviewed also worked with the gender policy units that local and provincial governments established (see Table 8). A significant benefit of working collaboratively and sharing information with other agencies is the reduction of duplication and the more effective use of scarce resources, as described by an employee at Station H:

The [Local] Board is useful to coordinate actions, to improve the failures in each case, to correct and to not repeat mistakes. There is an agenda for the topics that will be discussed. It provides information about how each agency works, the conditions of admission, what works in the repertoire of state agencies. We normally identify the agency’s referents, in order to work with the most difficult cases or the ones that require special treatment. It is often very useful to articulate because different agencies often do the same work and resources are wasted. (Police Officer, Station H)

Women’s police stations also work collaboratively with access to justice centres, the local ombudsman, the Justice of Peace and other educational institutions. The responses varied according to city or rural location, as some agencies did not exist outside metropolitan centres. Most worked closely with the courts (73 per cent) and with the Public Prosecutors Office (84 per cent). Most of our interviewees (82 per cent) described their work with organisations as being very useful to the prevention of violence against women (Table 8). Multi-agency collaborative approaches in response to gender-based violence are a policy approach that Australian jurisdictions are currently adopting. Victoria has recently opened an integrated service to support victims of domestic violence called ‘the Orange Door’, which is a response to the Victorian royal commission into family violence. In response to its royal commission, the Queensland government has undertaken an ‘integrated service response’ trial to ‘improve the safety and wellbeing of victims and their children, reduce risks posed by perpetrators and ensure strong justice system responses for perpetrators’ (Griffith Institute 2019: 1). Although promising, this integrated multidisciplinary approach is an ‘emerging practice’ that has yet to be rolled out across the state (Griffith Institute 2019: 2). Under the 2009 National Action Plan, Argentina has mandated an integrated service provision to the victims of gender violence. Women’s police stations, which have grown greatly in number since that law was passed, are a key element in the roll out of this novel policy.

The Limitations of Women’s Police Stations in Argentina

The capacity to undertake prevention work through women’s police stations is significantly hampered by insufficient resources. The vast majority of those interviewed (88 per cent) felt that they did not have adequate resources in relation to personnel, facilities, budget and working conditions to respond to their case load (see Table 9). Ideally, all victims should be received by the interdisciplinary professional team, but lawyers, social workers and psychologists are only available for certain lengths of time (e.g. 30 hours per week) or on certain days of the week.

Table 9: Resourcing and functioning of women’s police stations

|

Station

|

Do you think you have the adequate resources (personnel,

facilities, budget and working conditions) to respond to your case

load?

|

Do you think that the CMF in which you work fulfils its

objectives?

|

||||

|

|

Yes

|

No

|

No Answer

|

Yes

|

No

|

No Answer

|

|

A

|

0

|

11

|

2

|

6

|

1

|

6

|

|

B

|

3

|

6

|

0

|

5

|

0

|

4

|

|

C

|

0

|

11

|

0

|

7

|

2

|

2

|

|

D

|

4

|

4

|

2

|

6

|

2

|

2

|

|

E

|

7

|

0

|

1

|

4

|

0

|

4

|

|

F

|

0

|

12

|

0

|

12

|

0

|

0

|

|

G

|

0

|

12

|

0

|

7

|

1

|

4

|

|

H

|

0

|

9

|

0

|

4

|

3

|

2

|

|

I

|

0

|

8

|

0

|

7

|

1

|

0

|

|

J

|

0

|

8

|

0

|

7

|

1

|

0

|

|

Total

|

14

|

88

|

5

|

65

|

11

|

24

|

The facilities in some of the older premises were rudimentary, with one station not having gas for heating or adequate plumbing to allow clients to access toilet amenities. Few had adequately functioning toilet facilities, and others had outdated computers and broken printers and mobile phones. Staff had to buy their own paper, pens and toilet paper at seven of the stations. Two of the stations had holes in their ceilings, though one has since moved to a new premises in a much better state. About seven had fairly reliable police vehicles; however, all stations relied on local donors or agencies to provide maintenance, petrol and repairs. A comparison was often drawn to the common police, who had fleets of new police vehicles at their disposal. This led to a widely held perception among our interviewees that women’s police stations were under-resourced compared to common police stations in the Province.

The chronic under-resourcing of women’s police stations has been a common concern raised by studies in other Latin American countries (de Souza and Beccheri Cortez 2014; Osterman 2003: 478; Perova and Reynolds 2017: 190). Associated with this concern is the perception that women’s police stations are not valued as highly as common police stations precisely because they work with the victims of domestic and sexual violence.

Consistent with other studies of women’s police stations (Ashok 2018; Burton et al. 1999: 22; Jubb and Pasinato Izumino 2003: 17; Jubb and Wânia 2002; Ostermann 2003: 478–479), most of the policewomen we interviewed described their jobs as being stressful and explained how they wanted more assistance as frontline first responders to domestic and sexual violence. Although police work is generally regarded as involving demanding emotional labour (Martin 1999: 111), the emotional toll of listening to victims’ stories makes the job even more stressful than common police work:

It is not an easy job; the person attending needs and should have counselling, one also suffers violence. (Police Officer, Station A)

I think that working in this police station generates a lot of emotional charge ... I think that we should take more care of the staff working on these issues. (Police Officer, Station A)

A UN study of women’s police stations in Latin America also found that the intensity of daily interaction with victims of violence can substantially influence the mental wellbeing of police officers (Jubb 2010: 100). The study recommended counselling and self-care techniques for the officers who are engaged in this demanding emotional work (Jubb et al. 2010: 100). Despite the frustrations of limited resources and being unable to deliver appropriate levels of service to clients, most of those interviewed still felt that their women’s police stations fulfilled their objectives (see Table 9). Only 11 per cent felt that their station did not function as it should (see Table 9). Additionally, fundraising from local authorities, civil agencies and communities was crucial to all 10 stations, as they relied on donations of toys, clothing, cars, air conditioners, heaters, emergency support and furnishings to deliver services to their clients. This reliance on donations and the limitations of CMF resourcing must be considered in the context of the severe economic crisis in Argentina.

Summary of Study Findings and Limitations

The main limitation of our study is that it could not access the necessary data—rates of intimate female partner homicide by locality—needed to demonstrate the effectiveness of women’s police stations by comparing locations with stations to those that had none. Nor were we able to access the longitudinal data necessary to assess whether rates of intimate partner violence have been rising or reducing. We officially requested these data, but we were only given data for one year. Additionally, there are no comparable data for femicide on a global level, or even across Latin America, and counting femicide is fraught with complexity (Walklate et al. 2020). According to official court data for 2018, the Province of Buenos Aires had a femicide rate of 1.16 per 100,000—one of the lowest rates in Latin America (Corta de Suprema de Argentina 2019: 14). This rate is still lower than the global average of intimate partner homicide—1.3 per 100,000 of a female population—according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC 2018: 10). It is also lower than the rate of 1.3 in Oceania, 1.6 in the Americas and 3.1 in Africa (UNODC 2018: 10), as well as lower than most rates in Latin America (e.g., 10.2 in El Salvador and 5.8 in Honduras in 2017 [La Prenza 2018]).

Our methodology aimed to discover how women’s police stations in Argentina implemented strategies of responding to and preventing gender-based violence. We discovered that they achieved this in three main ways. First, they worked with victims to prevent the number of high-risk cases escalating to femicide, though our method cannot definitively measure this. By understanding domestic violence from a gender perspective, the multidisciplinary teams aim to break the cycle of domestic violence by using targeted and strategic interventions to work with victims and perpetrators and denaturalise violence. The chief obstacles to preventing gender violence are that most of it remains private and hidden in the family home (AIHW 2018: 5) and that victims, especially those most vulnerable (i.e., indigenous women), are least likely to report it to the police (Dowling et al. 2018). Specialist police stations for women overcome these obstacles by normalising women who seek their assistance and by not pathologising them. Unlike general police stations, specialist ones are designed to receive victims, not offenders. Importantly, specialist police stations for women—at least those in Argentina—do not prioritise a criminal justice response over the wishes of a victim. They respect victims’ agency over the state’s authority, which is a particularly significant issue for Indigenous women who may not wish to have a criminal justice response (Blagg et al. 2018; Nancarrow 2019).

Second, women’s police stations work in a coordinated fashion through Mesas Locales with other municipal and provincial agencies, such as the gender policy units. A significant benefit of working collaboratively with other agencies is the reduction of duplication, the more effective use of scarce resources and the sharing of information that is crucial to preventing gender violence within their locality. Working collaboratively and recognising that any agency is not alone responsible for responding to or preventing gender-based violence has been an adopted policy approach in Australian jurisdictions, though many of these programs are emerging practices (Griffith Institute 2019). However, the specialist police stations for women in Argentina go a step further in strategically navigating the distance between women as victims of gender violence and an array of government and judicial agencies. They can leverage their informal and formal networks of authority to assist in violence prevention.

Third, women’s police stations prevent gender violence through the large-scale educative influence of their community engagement activities, which aim to revert the norms that sustain violence against women. The multidisciplinary teams who work in women’s police stations are regulators of the social order, as well as ‘engines for change’ (Psychologist, Station C). Although our results are promising, knowing how much the teams’ preventative work with communities changes the local norms that sustain gender-based violence is difficult to gauge in a single time frame study such as ours. Only a longitudinal study could measure this influence.

Critical Reflections on the Limits and Virtues of Women’s Police Stations

The specialist police stations that we studied in Argentina have several virtues and limitations. The most significant virtue is that they overcome some of the systemic problems within traditional models of male-dominated policing that are experienced by women who report incidents of gender violence. While the proportion of women entering policing has increased in the last century,[7] policing remains a male-dominated profession in which masculine culture is pervasive, if not hegemonic (Loftus 2008: 757; Prokos and Padavic 2002: 242). The masculine culture that pervades frontline policing has serious and adverse implications for how police typically respond to gender-based violence (Douglas 2019; Goodman-Delahunty and Graham 2011; Loftus 2008; Prokos and Padavic 2002; Prenzler and Sinclair 2013; Pruitt 2013). Male officers can use the authority of their position and gender to exercise power in their interactions with women as citizens (Martin 1999: 118). There are many documented shortcomings regarding how this affects victims of gender violence who seek police support, including ambivalence and a lack of empathy towards the victims of domestic and sexual violence (Douglas 2018, 2019; Royal Commission 2017: 382–388; Taylor et al. 2013: 98–99, 107); failure to provide women with adequate information (Special Taskforce 2015: 230; Standing Committee on Social Issues 2012: 167; Westera and Powell 2017: 164–165); a lack of referral to appropriate support services in emergency and non-emergency situations (Ragusa 2013: 708; Westera and Powell 2017: 164–165); victim blaming (Douglas 2019; Goodman-Delahunty and Graham 2011: 36–37; Taylor et al. 2013: 99, 108, 154); reluctance to believe or take victims’ complaints seriously (Douglas 2019; Powell and Cauchi 2013: 233; Royal Commission 2017: 504; Special Taskforce 2015: 251; Taylor et al. 2013: 102, 156); ‘siding with the perpetrator’; and regarding victim’s complaints as ‘too trivial and a waste of police resources’ (Special Taskforce 2015: 251).

Indigenous women in Australia are 32 times more likely to experience family violence, which is the preferred term in Indigenous communities (AIHW 2018: 83). However, there is an absence of Indigenous-led and culturally appropriate violence prevention programs in Australia (Blagg et al. 2018; Douglas and Fitizgerald 2018; Nancarrow 2019). In Western Australia, Indigenous women who come to police attention for domestic violence can instead be taken into police custody for fine default. This is what happened to 22-year-old Ms Dhu on 14 August 2014, who was taken into custody and died two days later from the injuries she sustained from domestic violence (Fogliani 2016). The coroner described the police’s treatment of her ‘appalling’ and without regard for ‘her welfare and her right to humane and dignified treatment’ (Fogliani 2016: 165). In Queensland, police have also used their discretion to charge both male and female Indigenous partners with domestic violence violations that now carry terms of imprisonment. This has led to a rise in rates of Indigenous women’s imprisonment, who now account for 66 per cent of women imprisoned due to a contravention of the domestic violence order, but who only account for three per cent of the population in Queensland (Douglas and Fitzgerald 2018: 42). It is understandable that Indigenous women are unlikely to report family or partner violence to the police when they are circumstances in which they risk being jailed (Douglas and Fitzgerald 2018; Fogliani 2016; Gleeson 2019; Nancarrow 2019). Traditional models of policing in Australia have consistently failed Indigenous women who experience domestic and family violence.

Given the systemic shortcomings of traditional policing responses to victims of domestic and sexual violence, there is strong case for considering alternative policing models. There is a growing body of evidence indicating that specialised police forces that are designed to respond to gender-based violence will ameliorate some of the systemic problems in traditional policing models (Amaral et al. 2018: 3; Hautzinger 2002, 2007; Jubb et al. 2010; Miller and Segal 2018; Natarajan 2005).

Much debate exists regarding whether women’s police stations work better with victims of male violence simply because they share the same gender. This assumption has been rightly criticised as essentialist, which this article cautions against (Hautzinger 2002; Ostermann 2003; Santos 2004). Ana Ostermann (2003) conducted a discourse analysis of the language transactions between policewomen and women who work in women’s crisis centres in Brazil from an explicitly feminist perspective. Her study problematises the essentialist discourses that assume policewomen express more empathy towards female victims of violence simply because they are female too (Ostermann 2003). She argued instead that female police work in gendered communities of practice that have developed a certain habitus associated with the militarist style of male-dominated policing (Ostermann 2003: 477). Her linguistic analysis of how language operates to signpost power in interactions found that female police were four times less likely to be responsive to victims’ turns in conversation, compared to women who worked explicitly from a feminist community of practice (Ostermann 2003: 473). These findings are based on interviews in one women’s police station in Brazil, where unlike in Argentina, they do not have specialist training, nor the opportunity to choose to work in a specialist police station.

In the 1990s, Hautzinger conducted an ethnographic study of women’s police stations in the state of Bahia, Brazil. She argued that DDMs at that time were haunted by a contradiction: On one hand, DDMs essentialise policewomen as being naturally empathetic to other women. On the other hand, they are encultured in a masculinist profession of policing in which ‘machista’ values are internalised, such as those that lead to victim blaming (Hautzinger 2002: 246–247). Reflecting on her research, Hautzinger (2016) now argues that between 1985 and 2006, the effectiveness of Brazil’s women’s police stations was undermined by chronic resource shortages, partly due to the droves of women seeking assistance, which created backlogs and increased waiting times for assistance.

A consistent criticism of women’s police stations has been their chronic shortage of resources (Hautzinger 2002, 2016; Jubb et al. 2010; Nelson 1996; Perova and Reynolds 2017; Santos 2004). In part, this reflects the undervaluing of women’s police in a wider gendered institution of policing—a complaint that our interviewees from Argentina consistently raised. It also reflects the political and economic context of developing countries in the global south, in which police stations are under-resourced and the implementation of specialised police stations thus falls short of what was envisaged (Hautzinger 2002: 248). Like Santos (2004), Hautzinger concluded that women’s police stations represent the most extensive institutional response to gender violence by the Brazilian state and that they play a critical role in conveying to communities that violence against women is a crime (Hautzinger 2002: 248; 2016: 577–582). An evaluation of women’s police stations undertaken for the United Nations in Latin America similarly found that of the community members who were surveyed in the same locality, 77 per cent in Brazil, 77 per cent in Nicaragua, 64 per cent in Ecuador and 57 per cent in Peru felt that women’s police stations had reduced violence against women in their countries (Jubb et al. 2010: 4). The limitation of this study is that it is based on community perceptions and not on evaluative data.

A recent evaluation of DDMs in Brazil assessed the shifts in female homicide rates in 2,074 municipalities from 2004 to 2009, controlling for a number of variables. The presence of a DDM was the main variable. The evaluative study found that where DDMs existed, the female homicide rate dropped by 17 per cent for all women and by an astonishing 50 per cent for women aged 15–24 in metropolitan areas (a reduction of 5.57 deaths per 100,000) (Perova and Reynolds 2017: 193–194). On this basis, Perova and Reynolds concluded that ‘women’s police stations appear to be highly effective among young women living in metropolitan areas’ (2017: 188). The limitation with this study is that it used female homicide rates as a proxy for the rate of femicide, in the absence of any other available data.

Our study adds to the small, but growing, body of evidence on the important role of women’s police stations in increasing access to justice for victims of gender-based violence (Amaral et al. 2018; Carrington et al. 2019; Hautzinger 2002, 2007; Jubb et al. 2010; Natarajan 2005; Perova and Reynolds 2017). Empirical studies of women’s police stations in Latin America and India have consistently shown that women are more comfortable reporting to policewomen in a family friendly environment (Hautzinger 2002; Jubb et al. 2010; Miller and Segal 2018; Natarajan 2005: 91; Santos 2004). This body of research suggests that policewomen enhance other women’s willingness to report, which then increases the likelihood of conviction and increases access to several other services (e.g., counselling, health, legal, financial and social support) (Jubb et al. 2010; Perova and Reynolds 2017; Santos 2004: 50). Specialised women’s police forces in the postcolonial societies of the global south increase access to justice, empower women to liberate themselves from the subjection of domestic violence—thereby preventing re-victimisation—and work with the community to disrupt the patriarchal norms that sustain gender violence. As a by-product, they also offer women in the global south a career in law enforcement that is framed from a gender perspective. We thus conclude that other nations in the world, including in the global north, should learn from this unique model of policing gender-based violence. This research is important because eradicating violence against women is an UN SDG (UN 2016), and preventing gender violence a fundamental guiding framework of UN Women (2015).

Amaral S, Bhalotraz S and Prakash N (2018) Gender, Crime and Punishment: Evidence from Women Police Stations in India. Essex: Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), Research Centre on Micro-Social Change (MiSoC). Available at https://ideas.repec.org/p/bos/iedwpr/dp-309.html (accessed 18 February 2020).

Arango D, Morton M, Gennari F, Kiplesund S and Ellsberg, M. (2014) Interventions to prevent or reduce violence against women and girls: A systematic review of reviews. Women’'s voice, agency, and participation research series, no. 10. Available at http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/700731468149970518/Interventions-to-prevent-or-reduce-violence-against-women-and-girls-a-systematic-review-of-reviews (accessed 18 February 2020).

Ashok K (2018) Staff at women’s police stations lack training, sensitivity. The Hindu, 22 October. Available at https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/Delhi/staff-at-womens-police-stations-lack-training-sensitivity/article25281967.ece (accessed 18 Februrary 2020).

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) (2018). Family, Domestic and Sexual Violence in Australia 2018. Canberra: AIHW.

BA Provincia (n.d.) Mesas Locales Intersectorales. [A provincial government publication]Available at https://www.gba.gob.ar/file/descargas_144/Anexo1_Mesas%20Locales%20Intersectoriales.pdf (accessed 1 March 2016).

Blagg H, Williams E, Cummings E, Hovane V, Torres M and Woodley KN (2018) Innovative models in addressing violence against Indigenous women: Final report. Available at https://www.anrows.org.au/publication/innovative-models-in-addressing-violence-against-indigenous-women-final-report/ (accessed 18 February 2020).

Bull M, George N and Curth-Bibb J (2017) The virtues of strangers? Policing gender violence in Pacific Island countries. Policing and Society: An International Journal of Research and Policy 29(2): 155–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2017.1311894

Burton B, Duvvury N, Rajan A and Nisha Varia N (1999) Domestic violence in India: A summary report of three studies. International Center for Research on Women. Available at http://www.womenstudies.in/elib/dv/dv_domestic_violence_in_India_a_summary.pdf (accessed 18 February 2020).

Calandrón S (2008) Cultura institucional y problematicas de genero en la Reforma de la Policia de Buenos Aires, 2004–2007. PhD Thesis, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, Argentina.

Calandrón S (2014) Genero y Sexualidad en la Policia Bonaerense. San Martin, Buenos Aires: UNSAM Edita.

Calandrón S and Galenano D (2013) La ‘Brigada Femenina’: Incorporacion de mujeres a la Policia de la Provincia de Buenos Aires (1947–1955). In Salvatore R and Barreneche O (eds) El delito y el orden en perspectiva histórica: 167–186. Rosario: Prohistoria Edicionaes.

Carrington K, Hogg R and Sozzo M (2016) Southern criminology. British Journal of Criminology 56(1): 1–20. http://doi.org10.1093/bjc/azv083

Carrington K, M Sozzo, MV Puyol, N Guala, L Ghiberto and D Zysman (2019) The role of women's police stations in responding to and preventing gender violence, Buenos Aires, Argentina: Draft report for consultation. Queensland University of Technology, Australia.

Cartron A (2015) Women in the Police Forces in Britain: 1880–-1931. Master’s Thesis, Universite Paris Dederot, Paris.

Collins D (2017) Police Chiefs’ blog on the gender pay gap. British Association for Women in Policing. Available at https://www.npcc.police.uk/ThePoliceChiefsBlog/PoliceChiefsblogCCDeeCollinsClosingthepolicegender.aspx (accessed 13 November 2019).

Connell R (2007) Southern Theory: The Global Dynamics of Knowledge Social Science. Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin.

Corta de Sumprema de Justicia de Argentina, (2019) Femicidos: Datos Estadísticos del Poder Judicial., Buenos Aires: Oficina de Mujer, Buenos Aires.

de Souza, L and Cortez MB (2014) Women's defense police station towards the rules and laws for combating violence against women: A case study." Revista De Administração Pública 48(3): 621-664. https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-76121141

Douglas H (2018) Legal systems abuse and coercive control. Criminology & Criminal Justice 18(1): 84–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748895817728380

Douglas H (2019) Policing domestic and family violence. The International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 8(2): 1–49. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.v8i2.1122