|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy |

#Notallcops: Exploring ‘Rotten Apple’ Narratives in Media Reporting of Lush’s 2018 ‘Spycops’ Undercover Policing Campaign

Nathan Stephens Griffin

Northumbria University, United Kingdom

|

Abstract

This article examines the media framing of the 2018 ‘paid to

lie’ campaign of Lush, a high-street ethical cosmetics firm.

The viral

nature of Lush’s intervention into the undercover policing of activism in

the United Kingdom highlights the significance

of media reporting in the

construction of narratives surrounding policing and activism. A qualitative

content analysis was undertaken

of articles published online in the immediate

aftermath of the campaign launch. Based on this analysis, this article argues

that

the intensely polarised debate following Lush’s ‘paid to

lie’ campaign is representative of a wider discursive

framing battle that

continues to persist today. Within this battle, the state and police

establishment promote ‘rotten apple’

explanations of the undercover

policing scandal that seek to individualise blame and shirk institutional

accountability (Punch 2003).

This is significant, as identifying systemic

dimensions of the ‘spycops’ scandal is a key focus for activists

involved

in the ongoing Undercover Policing Inquiry (Schlembach 2016).

Keywords

Undercover policing; media; activism; rotten apples.

|

Please cite this article as:

Stephens Griffin N (2020) #Notallcops: Exploring ‘rotten apple’ narratives in media reporting of Lush’s 2018 ‘spycops’ undercover policing campaign. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy. 9(4): 177-194. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.v9i4.1518

Except where otherwise noted, content in this journal is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence. As an open access journal, articles are free to use with proper attribution. ISSN: 2202-8005

In June 2018, many consumers in the United Kingdom (UK) were surprised to see what appeared to be police tape adorning the storefronts of the ethical cosmetics chain Lush. A closer inspection revealed a carefully planned awareness raising campaign, highlighting harmful cases of police spying on activists. Lush’s campaign generated significant media interest. This article argues that the heavily polarised debate, which immediately followed the launch of Lush’s ‘paid to lie’ campaign, can be understood as part of a wider discursive framing battle that continues to persist between activists and the state. A central contention raised by spied-on activists related to the systemic nature of the harms perpetrated by the state. The state responded to the allegations about the ‘spycops’[1] by attempting to individualise blame and amplify ‘rotten apple’ explanations for the scandal. Specifically, the state placed responsibility on individual officers rather than systemic police practices and thus sought to shirk institutional accountability.

Debates surrounding the spycops case have frequently been diverted away from the harm done to the activists and the problematic nature of the criminalisation of protest towards parallel discussions about which organisations and actors are entitled to make political arguments and how such arguments should be conducted. This paper empirically shows how ‘rotten apple’ explanations have come to dominate media reporting of cases of police misconduct. In doing so, this paper contributes to the critical criminological literature on the spycops case (Apple 2019; Fitzpatrick 2016; Loadenthal 2014; Lubbers 2015; Schlembach 2016, 2018; Spalek and O’Rawe 2014; Woodman 2018a 2018b; Stephens Griffin, forthcoming). This paper also contributes to critical media studies on the role of the media in manufacturing consent for mainstream ideologies and systems of domination (Almiron, Cole and Freeman 2018; Cammaerts 2015).

This article begins by discussing some high-profile cases of police misconduct, before outlining the background to the spycops case and the Lush campaign. It then discusses the criminalisation of protest by placing the research in a theoretical context. Specifically, it considers Punch’s (2003) discussion of ‘rotten apple’ explanations for police wrongdoing. Next, an outline is provided of the methodology used to conduct the qualitative content analysis (QCA) of online news articles, including how the sample was selected and the data were analysed. An in-depth discussion of the findings is then undertaken. The discussion is structured around the three core themes that emerged from the research: 1) #notallcops narratives, which emphasise that in highlighting the abuses in the way it did, the campaign unfairly tarred all police officers with the same brush; 2) responsibility and risk narratives, which emphasise that the campaign was in some way reckless and/or dangerous; and 3) confusion narratives, which emphasise that the campaign was bizarre and/or that it was inappropriate for a high-street firm to behave in this way. Finally, this article concludes by discussing the implications from this case for campaigns against intimate state surveillance.

First, to contextualise this study, it should be noted that, an international pattern exists whereby ‘rotten apple’ explanations are initially used to ignore or dismiss police misconduct and corruption, before this misconduct and corruption are ultimately shown to be the result of widespread systemic practices. For example, the 1994 Mollen Commission into corruption in the New York Police Department (NYPD) revealed that instead of addressing corruption, the NYPD had permitted a culture that fostered misconduct and concealed the lawlessness of police officers, which enabled corruption to flourish at every level (Raab 1993). In Australia, the 1997 Wood Royal Commission investigated corruption in the New South Wales police force (its remit was later extended to investigate the activities of organised paedophile networks) (Brown 2007). Ultimately, the Wood Royal Commission concluded that a state of ‘systemic and entrenched corruption’ existed within the New South Wales police organisation (Chan and Dixon 2007: 443). The ‘Rampart scandal’ broke due to widespread corruption within the anti-gang unit of the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) in the late 1990s (Kaplan 2009). The corruption was so widespread that over 70 officers were implicated and more than 20 officers were fired or resigned (several of whom were convicted on criminal charges) (Kaplan 2009).

The police response to the racist murder of London teenager Stephen Lawrence in 1993 in the UK provides another significant example of police misconduct. As a result of the botched investigation, no criminal conviction was secured for Lawrence’s murder for almost 20 years. An official inquiry concluded that the London Metropolitan Police Service was ‘institutionally racist’ (MacPherson 1999). Notably, media interest in this case was initially limited. The Daily Mail even ran a story criticising anti-racist protestors for capitalising on the murder (Burrell and Peachey 2012). However, the victim’s father, Neville Lawrence, who had previously done plastering work in the home of the then Daily Mail editor Paul Dacre, was able to challenge Dacre directly, an action that prompted a shift in the paper’s editorial interest in the case (Burrell and Peachy 2012). The Daily Mail went on to run a now infamous front page with photographs of the five men suspected of killing Lawrence, under the headline ‘Murderers’ (Burrell and Peachey 2012). Home Secretary Jack Straw later stated that the Daily Mail’s coverage of the case had partly inspired his decision to order an official inquiry (Burrell and Peachey 2012). This example shows the significant role that media reporting can play in the success of official inquiries.

The spycops case first came to the attention of the mainstream public in 2011, following a newspaper article that sought to expose Mark Kennedy, an undercover officer in the National Public Order Intelligence Unit. Kennedy had been initially exposed by activists in 2010, following a seven-year deployment in which, using the identity ‘Mark Stone’, he infiltrated a number of leftist groups and entered into romantic and sexual relationships with deceived targets. Kennedy’s exposure led to the exposure of several other spycops. It is believed that over 150 spycops spied on over 1,000 activist groups between 1968 and 2010. The majority of groups that were targeted were left wing (Woodman 2018a 2018b). Perhaps the most notable individual to be exposed in the initial wave was Special Demonstration Squad officer Bob Lambert (Evans and Lewis 2013b). Lambert’s deployment has become particularly infamous due to his having fathered a son while undercover (Evans and Lewis 2013b). The Metropolitan police subsequently paid the mother of Lambert’s son £425,000 in an out-of-court settlement (Casciani 2014). Lambert’s son, who only discovered his father’s true identity when he was 26 years old, is currently suing the Metropolitan police for psychiatric damage (Evans 2017a). It is believed that more than 20 officers engaged in the practice of entering into sexual relationships by deceiving targets. Spycops were also shown to have adopted other highly controversial tactics while undercover, including assuming the identities of dead children without the consent of their families, participating in criminality while posing as activists and appearing in court under false identities (Apple 2019; Evans 2018b).

In 2015, Teresa May (the then UK Home Secretary) announced an inquiry into undercover policing (i.e., the Undercover Policing Inquiry [UCPI]). The commencement of the UCPI is largely attributable to the intervention of ex-spycop turned whistle-blower Peter Francis, who revealed that he had been instructed to spy on and ‘smear’ the family of Stephen Lawrence as they campaigned for justice (Evans and Lewis 2013a). The UCPI has been heavily criticised by activists for being slow moving and overly secretive (Schlembach 2016). A key dimension in the campaign for truth and justice in this case was the lack of acknowledgement of systemic accountability (Campaign Opposing Police Spies [COPS] 2019). In May 2018, core participants of the UCPI staged a walk-out over what they described as an attempted cover-up by the police (Evans 2018c). The perceived inadequacies of the UCPI were instrumental in laying the foundations for Lush’s eventual involvement in the spycops case.

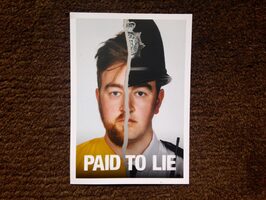

The high-profile intervention into the spycops campaign by Lush (a UK high-street ethical cosmetics firm) represents one of the most surprising recent developments in relation to the case. Lush publicly lent its support to spycops campaigners as part of a nationwide campaign, which launched in stores on 1 June 2018. Working in connection with the campaign groups COPS and Police Spies Out of Lives (PSOL), Lush’s campaign sought to highlight abuses by undercover police officers in the UK (Lush 2018b). The campaign involved the use of window displays across Lush’s UK stores. The imagery deployed in the campaign included mock police tape with the words ‘police have crossed the line’, the tagline ‘paid to lie’ and a striking visualisation of a police spy (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Lush ‘paid to lie’ campaign poster

The stated aims of the campaign were to raise awareness about the spycops case, to push for changes in the current public inquiry and to demand genuine accountability from the state (Dancey-Downs 2018). As part of the campaign, shoppers were invited to fill out postcards in stores to be sent to the Home Secretary demanding that a panel of experts be appointed to assist the Chair of the Inquiry, Sir John Mitting and that the UCPI to be extended to include Scotland, where Kennedy and other spycops were known to have been active (Dancey-Downs 2018). The postcards also demanded the release of the cover names of the officers, the names of the groups on whom they spied and copies of the personal files on victims held by police (Dancey-Downs 2018). It should be noted that Lush has a history of lending its support to causes that may be considered ‘divisive’; for example, Lush has lent its support to Palestinian solidarity (Ghert-Zand 2011), animal rights (Sea Sheppard 2008) and Syrian refugees (Lush 2018a).

Segments of the police and the public responded furiously to the campaign. Senior figures in the police and the government condemned the campaign, including the then Home Secretary Sajid Javid. This was coupled with widespread criticism of the campaign on social media. The hashtag #FlushLush began to trend in the UK. Additionally, in response to a call from a Facebook page called ‘UK Cop Humour’, Lush’s UK Facebook page received tens of thousands of negative reviews (Boyd 2018; Saner 2018). According to a social media analysis conducted by Brandwatch, Lush’s twitter mentions jumped by 2,321% in the space of 24 hours (Boyd 2018) with negative comments far outweighing positive ones. Excluding neutral comments, 67% of all comments made on social media on 1 June 2018 were negative in tone. Notably, before the launch of the campaign, Lush regularly enjoyed a rate of 80% positive comments (Boyd 2018). Some Lush stores faced threats and harassment in relation to the displays, leading some stores to temporarily suspend the campaign for the ‘safety of staff’ (Evans 2018b). In response to the backlash, Lush issued a clarification insisting that the campaign was not about ‘the real police work done by those front line officers who support the public every day’ but ‘a controversial branch of political undercover policing that ran for many years before being exposed’ (Lush 2018b).

The temporary suspension of the campaign on 3 June 2018 was followed by the total withdrawal of the campaign on 8 June 2018. A revised version of the campaign was launched on 13 June 2018 in which the image of the police officer had been removed. Lush clarified its decision, stating ‘we have taken away the distraction of, what turned out to be, a controversial visual to return the focus onto the shocking facts’ (Alibhai 2018). However, despite the furious backlash, the campaign also garnered significant support. The campaign film on Lush’s website was viewed over one million times and Lush’s sales increased by 13% in the immediate aftermath of the campaign’s launch (Saner 2018). Many commended the campaign, including various individuals who had been directly affected by police spying. Further, a number of people spoke out in defence of the campaign in newspaper comment pieces, including the ex-wives of undercover officers, undercover officer Bob Lambert’s son and Doreen Lawrence and John McDonnell[2] (Lawrence and McDonnell 2018; S and HAB 2018).

Criminalisation of Protest

The critical criminological literature has sought to highlight both the structural relations of power in which policing occurs under capitalism (Hall et al. 1978; Scraton 1987; Taylor, Walton and Young 1973) and the invisibility of crimes of the powerful more broadly. Examining the diverse harms that are frequently rendered invisible in society, Davies, Francis and Wyatt (2014) attempted to map the contours of this invisibility and by doing so, offered a theoretical framework for identifying the features of invisible crime and harm. The authors identified seven features of invisibility that affect the identification of certain acts as ‘criminal’, including a lack of knowledge (whereby members of the public are not aware a crime has been committed), a lack of statistics (whereby official statistical measures fail to account for such crimes) and a lack of research into such areas (often due to the inaccessibility and practical constraints of conducting research in such areas). It is useful to explore media responses to the Lush spycops campaign, as this campaign explicitly sought to raise awareness and make visible a previously invisible example of police abuse (i.e., state crimes).

In addition to important work on the criminalisation of protest more broadly (Ellefsen 2016; Jackson, Gilmore and Monk 2018; Lovitz 2010; Potter 2011), a growing body of research directly focused on the spycops case has emerged in recent years, including work by Apple (2019), Fitzpatrick (2016), Loadenthal (2014), Lubbers (2015), Schlembach (2016, 2018); Spalek and O’Rawe (2014), Woodman (2018a 2018b) and myself (Stephens Griffin, forthcoming). This research has shown that terms such as ‘terrorist’ and ‘extremist’ were inconsistently and opportunistically employed to delegitimise resistance movements targeted at spycops (and other movements more broadly) and justify surveillance and repression (Choudry 2019; Schlembach 2018). Loadenthal (2014) argues that intimate state surveillance was deliberately employed to ‘atomise’ resistance movements and destroy bonds of trust within those movements to limit their power and success. Choudry (2019) argues that the spycops case must be understood in the context of the longstanding use of police, state and private security to repress and undermine political groups in Western liberal democracies. Having interviewed environmentalists who had been subject to intimate state surveillance, I found that the spycops caused some activists to cease engaging in activism altogether, while others refocused their efforts away from environmentalism towards anti-state surveillance activism (Stephens Griffin, forthcoming).

Rotten Apples or Rotten Orchards

Scholarship around state crime and the crimes of the powerful more generally has demonstrated the discursive processes by which systemic problems can be dismissed or isolated to avoid institutional accountability. The ‘rotten apple that spoils the barrel’ is a widely understood metaphor used to explain wrongdoing within institutions. It posits that a single bad (or malign) actor among many good (or benign) actors can spoil those around them and tarnish the reputation of the group as a whole. Further, and perhaps more importantly, it implies that institutional problems can be solved by removing that one bad actor. The metaphor of the rotten (or bad) apple has often been employed to explain instances of state and corporate wrongdoing, making scapegoats of individuals or small groups of actors who are held culpable of the transgressions while maintaining the legitimacy of the state or corporate institutions. Allowing such explanations to predominate also enables the exposure of individual wrongdoing to be interpreted as ‘testimony to the integrity of the system which dealt with it’ (Chibnall 1977 in Greer and Reiner 2012: 252). Thus, such transgressions are understood as exceptions that by their very identification prove the rule that the system is working. Stark (1972 cited in Lersch and Mieczkowski 2005) argues that ‘rotten apple’ explanations provide scapegoats, who become the primary vessels for public outrage and thus enable more significant questions about the institutional dynamics in which these harms were perpetrated to be evaded. Scholars have highlighted instances in which ‘rotten apple’ explanations have variously been used to explain state crime and police misconduct (Stark 1972), miscarriages of justice (Punch 2003), the mishandling of the Stephen Lawrence’s murder (Hall 1999), corporate crimes (Tombs 2004) and the abuse of prisoners at Abu Ghraib (Wood 2016).

Focusing on policing, Punch (2003) conducted a comparative analysis of cases of police misconduct across Europe, using official reports and newspaper sources to provide an empirical basis for claims surrounding ‘rotten apple’ explanations. Punch’s research highlights the deployment of the ‘rotten apple’ metaphor across a wide range of cases, including three infamous UK police misconduct–related miscarriages of justice relating to the Irish Republican Army, the Birmingham Six, the Guildford Four, the case of Judith Ward, the Dutroux Case in Belgium and the Interregionaal Recherche Team or ‘IRT’ case in the Netherlands. Punch argues that collectively such cases represent instances of institutional culpability, whereby miscarriages of justice occur as a result of the collusion of actors across the criminal justice system. In the UK example, this included front line police officers, senior police officers, forensic scientists, members of the judiciary and the Home Office itself (by its resisting calls for appeals in these cases). Punch (2003) employs an alternative ‘rotten orchard’ metaphor to explain the wider system failure that enabled these miscarriages of justice to take place. Further, Punch argues that systemic change must take place following cases of systemic failure if confidence is to be restored and that ‘the more “systemic” the deviance, the more profound and far-reaching the changes have to be’ (Punch 2003: 194).

Methodology

In this study, a QCA was undertaken of 80 articles related to the Lush campaign and its subsequent controversy. A QCA necessitates an in-depth careful examination of the use and intended effect of language in text (Moore 2014). The adoption of such an approach is rooted in interpretivist epistemological assumptions and a social constructionist theoretical framework. The approach sought to rigorously interrogate the way in which discourse surrounding spycops can be best understood.

Methods

Using a purposive sample, the study qualitatively examined online articles on the Lush campaign and subsequent controversy. Each text had to meet the sampling criteria for inclusion in the study. Specifically, to be eligible for inclusion, a text had to:

- focus on the Lush Spycops campaign of 2018; and

- have been published between 1 June 2018 and 30 June 2018 (i.e., during the immediate aftermath of the campaign launch).

Initially, a combination of Nexis database and Google searches were conducted to develop the sample. In conducting these searches, combinations of the keywords ‘Lush’, ‘Spycops’ and ‘Undercover Policing’ were employed. Once a sufficiently large base of relevant articles had been identified, an initial skimming process was used to eliminate duplicate articles and any articles that failed to meet the sampling criteria (e.g., articles were excluded if they only contained oblique references to the campaign or had been published outside the sampling criteria period). The final sample comprised 80 articles from 51 different publications.

Sources from which online articles were drawn included online news channels (e.g., BBC and Sky News), broadsheet newspapers (e.g., the Telegraph and the Guardian), middle-market tabloids[3] (e.g., the Daily Mail and the Daily Express) other tabloids (e.g., The Sun and the Metro), local news sources (e.g., the Liverpool Echo) and a variety of other online specialist sources and business/advertising websites (e.g., MarketingWeek.com, BrandWatch.com and Teen Vogue).

The vast majority of articles identified were news articles (e.g., ‘Lush Anti-Spycops Campaign Criticised’, BBC, 1 June 2018); however, the sample also included feature and analysis pieces (e.g., ‘How will Lush’s anti spycops campaign play with its target audience’, YouGov, 27 June 2018) and opinion and comment pieces (e.g., ‘Why we need Lush's spycops campaign’, New Internationalist, 4 June 2018).

Data Analysis

Following the initial QCA, a quantitative analysis was undertaken to identify and categorise broad patterns in the tone and content of the articles. This allowed for a more robust and rigorous QCA process, which, in line with the interpretive approach, was conducted with sensitivity to both the surface meaning and underlying subtext. The process of thematic coding involved asking questions about the explicit message and apparent aims and purpose of each article to examine the key topics addressed in each article. This process was also sensitive to who was being quoted in articles and the wider context of historic instances of police misconduct. As discussed above, three broad themes were identified from the QCA: 1) #notallcops narratives; 2) responsibility and risk narratives; and 3) confusion narratives. These three themes do not represent the totality of the news coverage; however, they do reflect the three most dominant themes identified by the research. The three themes are discussed in further detail below; however, it should be noted that the qualitative themes identified in the articles were drawn from across the sample and were not limited to articles that framed the Lush campaign in negative terms.

Limitations

The study comprised a limited sample of 80 articles. This sample sought to capture a representative range of articles published within the sampling criteria period; however, it does not purport to definitively and exhaustively capture all of the articles published in response to the Lush #spycops campaign. A concerted effort was made to undertake a comprehensive overview of the content published within the set period to increase the reliability of the research. The research is replicable (i.e., someone else could carry out the same systematic search and produce similar results in terms of building the sample); however, the qualitative nature of QCA means that the data analysis is less replicable than the process of building the sample. Reliability and generalisability were not the primary aims of the present study, which may represent a potential limitation of the study. However, a rigorous and systematic approach was used to build the sample that could be replicated in other instances.

A further limitation of this approach is that there was no direct analysis of social media content in response to the Lush campaign. This is a drawback because the Lush campaign and resulting backlash played out across social media. Notably, there is an indirect analysis of social media content via the media reporting of social media responses. Notably, this article refers to data from a social media analysis conducted by Brandwatch (Boyd 2018).

Certain publications, such as the Daily Mail and the Guardian, provide insight into the reach of an article via the number of comments made in respect of the article, as well as via indicators as to how many times an article has been shared (e.g., one Daily Mail article referred to in this article had been shared 1,100 times and had over 400 comments). However, the research did not seek to engage with the most ‘widely-shared’ articles; rather, it simply focused on those that concerned the topic and did not take into account the ‘reach’ or ‘engagement’ aspects of the data. As this study focused on the qualitative content of the articles and not their tangible impact, little is known about how widely some of the articles from smaller publications were read.

Quantitative Overview

Given the variety and complexity of reporting on the topic, providing a sense of the overall tone and character of the articles analysed could be viewed as simplistic; however, it is also useful. Overall, approximately half (n = 43, 53.75%) of the articles in the sample were found to have a broadly negative view of or had foregrounded critical perspectives on the Lush spycops campaign, approximately one quarter (n = 22, 27.5%) of the articles were coded as neutral or broadly impartial in tone and just under one fifth (n = 15, 18.75%) had a generally positive tone or foregrounded favourable perspectives on the campaign.

Table 1: Media Framing of the Lush Campaign

|

Framing

|

Broadsheet

|

Middle-Market Tabloid

|

Tabloid

|

Online News

|

Online Specialist

|

Local News

|

Total

|

|

Positive

|

9

|

1

|

1

|

2

|

2

|

0

|

15

|

|

Neutral

|

5

|

0

|

1

|

2

|

10

|

4

|

22

|

|

Negative

|

6

|

5

|

7

|

6

|

8

|

11

|

43

|

|

Total

|

20

|

6

|

9

|

10

|

20

|

15

|

80

|

As Table 1 shows, broadsheet newspapers and online specialist websites published more articles on the topic in general (each accounting for n = 20 articles), followed by local news sites (n = 15), online news (n = 10), tabloids (n = 9) and middle-market tabloids (n = 6). Articles were almost twice as likely to be negative (n = 43) about the Lush campaign than neutral (n = 22) and more than twice as likely to be negative than positive (n = 15). Breaking the sample down by type of publication, broadsheet newspapers were more likely to be positive (n = 9) than neutral (n = 5) or negative (n = 6). Conversely, tabloids were more likely to be negative (n = 7) than neutral (n = 1) or positive (n = 1). Specialist sites tended to be more neutral (n = 10) or negative (n = 8) about the campaign than positive (n = 2). Local news was entirely neutral (n = 4) or negative (n = 11) a no articles described the campaign favourably.

Table 2: Article Type by Source

|

Article Type

|

Broadsheet

|

Middle-Market Tabloid

|

Tabloid

|

Online News

|

Online Specialist

|

Local News

|

Total

|

|

News

|

13

|

6

|

8

|

10

|

15

|

14

|

66

|

|

Opinion/Comment

|

6

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

2

|

1

|

10

|

|

Feature/Analysis

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

3

|

0

|

3

|

|

Letters

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

|

Total

|

20

|

6

|

9

|

10

|

20

|

15

|

80

|

Table 3: Framing by Article Type

|

Framing

|

News

|

Opinion/

Comment

|

Feature/

Analysis

|

Letters

|

Total

|

|

Positive

|

8

|

6

|

0

|

1

|

15

|

|

Neutral

|

17

|

2

|

3

|

0

|

22

|

|

Negative

|

41

|

2

|

0

|

0

|

43

|

|

Total

|

66

|

10

|

3

|

1

|

80

|

The analyses by source (see Table 2) and article type (see Table 3) revealed that opinion pieces and letters published in the period were mostly positive about the campaign. Conversely, features and analysis pieces published in the period were generally neutral. A more refined qualitative thematic analysis was also conducted (see below).

Themes

As mentioned above, three key themes were identified in the sample. These were organised under the following headings: #notallcops narratives, which emphasised that in highlighting these abuses in the way it did, the campaign unfairly tarred all police with the same brush; responsibility and risk narratives, which emphasised that the campaign was in some way reckless and/or dangerous; and finally, confusion narratives, which emphasised that the campaign was bizarre and/or that it was inappropriate. Each of these themes is discussed in further detail below.

#Notallcops narratives

The dominant theme to emerge from the sample related to the perception that Lush’s campaign had unfairly smeared the wider police population with the same brush by highlighting the spycops’ abuses. This narrative links directly to the ‘rotten apple’ notion and arguably, suggests a ‘rotten apple’ explanation for the spycops scandal. This narrative represents a core dimension of the framing battle in relation to the campaign, as #notallcops narratives conflicted with the central aims of the Lush campaign, which were to raise awareness about the spycops case, push for changes to the current public inquiry and demand genuine accountability from the state. Examples of the #notallcops narrative and the way in which it reflects this framing battle are discussed further in this section.

The assertion that the Lush campaign was ‘anti-police’ was foregrounded in much of the media coverage. For example, the following passage appeared in an article by Riley (2018) published in the Daily Mail on 1 June 2018:

Bosses at the Advertising Standards Authority have today announced they are launching a probe into the campaign which has been branded ‘anti-police’ by customers and some former officers. ... Former police officer Peter Kirkham said: ‘Your anti police advertising campaign is an utter disgrace. It stereotypes ALL police officers as corrupt and includes some fundamental misrepresentations of the facts. I trust that you will never again seek police assistance if you are the victims of crime.’

Notably, reporting of this nature foregrounded the perspectives of police officers, families of police officers, politicians and seemingly random twitter users who took offence to the campaign. A number of articles gave prominence to the then recently appointed Home Secretary Sajid Javid’s views on the case. In an article published in the Evening Standard on 2 June 2018, entitled ‘Home Secretary Sajid Javid launches scathing attack on Lush over “anti-police” ad campaign’, De Peyer (2018) stated: ‘Mr Javid, who was promoted to Home Secretary in April, said: “Never thought I would see a mainstream British retailer running a public advertising campaign against our hardworking police.”’

Javid’s statement is significant, as his view became part of the story and also provided the framework through which the discussion continued from that point forward. This narrative predominantly emanated from the state itself and was willingly repeated by dominant media sources. The Home Secretary’s comments encapsulated the tone of much of the discussion surrounding the campaign with other state actors. Notably, senior police figures also offered similarly outraged responses, which were foregrounded in reports. The ‘hard-working’ police narrative is further evidenced in an opinion piece written by Durham Constabulary Chief Constable Mike Barton published in the Northern Echo on 12 June 2018 in which Barton (2018) stated:

My objection to the advertisement by Lush is the insinuation that all police officers, and in particular police officers in uniform, were part of this controversy. That is not the case and, whilst I am in accord with Lush that what went on in the past is absolutely unacceptable, what is equally unacceptable is that the innocent are blamed. All organisations get things wrong from time to time. Policing UK has over 100,000 officers. Some of them transgress and just like any other professional body we have to ensure we have robust but fair procedures for rooting out the bad ones.

Barton’s (2018) concern was directed towards the ‘innocent’ officers being ‘blamed’ rather than the victims of the police abuse. He dismissed any notion of institutional culpability arguing that ‘all organisations get things wrong from time to time’ and that the solution to such problems is to ensure that there are ‘robust but fair procedures for rooting out the bad ones’ (Barton 2018). This is almost the very definition of the ‘rotten apple’ explanation for wrongdoing rejected by victims and core participants of the UCPI.

Other senior figures whose responses were given primacy in reporting include Calum Macleod (Chair of the Police Federation), who described the campaign as ‘offensive, disgusting and an insult to the hard work, professionalism and dedication of police officers throughout the UK’ (Rudgard 2018). Similarly, Ché Donald (Vice-Chairman of the Police Federation) stated ‘this is [a] very poorly thought out campaign and damaging to the overwhelmingly large majority of police who have nothing to do with this undercover enquiry’ (De Peyer 2018). Lynne Owens (Director General of the National Crime Agency) stated: ‘Undercover policing is a highly specialized and regulated tactic undertaken by brave officers to protect the public from the most serious offenders’ (Powell 2018). Evans and Kitching (2018) quoted a post to the Facebook page ‘UK Cop Humour’ in which an anonymous police officer wrote:

Whilst I can see there may have been good sentiment behind your latest campaign, it has been appallingly executed. Believe me nobody wants to see a corrupt practice or a corrupt officer held to account more than a decent hard-working officer. Unfortunately, your abhorrent window display depicts something far more sinister.

The focus on the hypothetical ‘corrupt officer’ versus the ‘decent hard-working officer’ individualised the problem and diverts the discussion away from systemic or institutional concerns. Notably, Lush’s statement in response to the backlash appears to have accepted the framing of much of the criticism and reinforced the preoccupation with the ‘hard-working’ officers that the campaign had insulted or offended. Specifically, Lush (2018b) stated:

This is not an anti-state/anti-police campaign. We are aware that the police forces of the UK are doing an increasingly difficult and dangerous job whilst having their funding slashed. We fully support them in having proper police numbers, correctly funded to fight crime, violence and to be there to serve the public at our times of need.

This campaign is not about the real police work done by those front line officers who support the public every day—it is about a controversial branch of political undercover policing that ran for many years before being exposed. Our campaign is to highlight this small and secretive subset of undercover policing that undermines and threatens the very idea of democracy.

This statement, which was quoted in articles both sympathetic and hostile towards the campaign, appears to inadvertently accept a ‘rotten apple’ framing premise in relation to the spycops scandal, localising the problem within a ‘controversial branch’ of undercover policing. By accepting the premise that the feelings of ‘front line police’ officers need to be protected in discussions of this nature, the institutional aspect of the abuse is minimised in the discourse. A key dimension of the truth and justice campaign rests on the desire to ascertain the extent to which spycops were doing as they were told and the ways in which they were instructed and supported by the police hierarchy and state to do so (Evans 2018d).

These #notallcops narratives represent the clearest distillation of the ‘rotten apple’ explanations surrounding the spycops scandal, as described by Punch (2003). They diverted discussions away from the harms perpetrated and the matters of accountability, truth and justice to a hypothetical discussion of ‘good’ versus ‘bad’ police officers. Such narratives frame the discussion in terms of the individual character of police officers and completely ignore the institutional and structural dynamics of the cases. This is a key dimension to the framing battle that persists in relation to the spycops case in which institutional and establishment explanations, foregrounded by the media, clashed with those offered by activists and victims. Punch (2003) argues that, in the wake of cases of police misconduct, institutions struggle to acknowledge the cases in which deviance has become systemic. A key dimension of the campaign for truth and justice in this case relates to the lack of acknowledgement of systemic accountability. In many of these examples, the notion of institutional culpability is completely invisible. The media’s foregrounding of these #notallcops narratives in the wake of the campaign contributed to the ‘rotten apple’ narrative surrounding the spycops scandal.

Responsibility and Risk Narratives

Another theme identified relates to responsibility and risk. This theme relates to sources that suggest that the Lush campaign was in some way reckless, irresponsible and potentially dangerous. In some instances, the campaign was explicitly criticised for undermining public support of the police. This view was encapsulated in Sajid Javid’s widely reported claim that ‘this is not a responsible way to make a point’ (in De Peyer 2018). The idea that the campaign posed a real risk to working police officers was a common theme in reporting. For example, Barlow (2018) quoted a retired police officer as saying ‘on Friday and Saturday evenings, people [could] pick up on this and throw it back at the police’. The idea that any criticism of the police could result in violence towards police provided a useful means for suppressing legitimate criticism and diverting attention from the campaign’s focus. Foregrounding this hypothetical risk to the safety of police in reporting helped to shift focus from the actual harms perpetrated by the police to the putative risks that front line officers face as they try to do their jobs.

One notable example of this was an attempt to implicate Lush’s campaign as contributing to low reporting rates for victims of child grooming and sexual abuse. In a comment piece for Metro (Davies 2018), Labour District Councillor Merilyn Davies, whose husband is a police officer, stated:

Trust in the police is a valuable thing. It gives those affected by crime the confidence to report it, in the belief they will be helped. Recent child grooming cases brought this home in a stark way; young girls did not trust the police and were horrifically abused, in part, because of this lack of trust. There should be no barriers to prevent young girls from calling on the police when they need help. Where there are barriers, we must tear them down, not build them higher. Unfortunately, in their misguided campaign, Lush have done just that.

Putting aside the fact that this campaign was largely predicated on victims of sexual abuse speaking out, the above narrative published by Metro appears to wilfully disregard the idea that the coercive sexual abuse perpetrated by undercover officers could itself be damaging to public trust; rather, the narrative accuses the victims whose voices were foregrounded in Lush’s campaign of harming other victims by speaking out about their experiences. The logic is that one must not speak out about abuse by police for fear of stopping other victims of abuse from speaking out. It also wilfully ignored accusations of institutional sexism that had been levelled at the Metropolitan police (PSOL 2019).

As illustrated by the headline ‘Lush had the right idea but the wrong execution’ (BJL 2018), some comment pieces stressed that theirs was a criticism of the way in which the message had been presented rather than a disagreement with the premise that the police spying had been harmful. This further reinforced the idea that Lush had a responsibility only to discuss these matters in a very specific way that did not pose unnecessary risk to officers. Conversely in a comment piece, Asfal (2018) criticised the spycops campaign stating, ‘poor execution, with zero context, has led to an outcry that the company probably foresaw’. This comment again demonstrates the theme of responsibility and risk.

Also falling under the thematic heading of responsibility and risk were several articles that discussed the abuse and threats faced by Lush staff as a result of the campaign. For example, in an article entitled ‘Lush remove #Spycops posters from some shops after 'intimidation from ex-police officers’ Wheaton (2018) stated, ‘Cosmetics chain Lush has removed its controversial campaign posters from some shops after it claimed to have been facing intimidation from ex-police officers ...’.

Present within the narratives of responsibility and risk was also the notion that police protection was somehow conditional on support. For example, Christine Fulton, whose police officer husband was killed on duty in 1994, was quoted in a number of articles as saying ‘who do Lush call when their stores are broken into?’ (Read 2018). This also reflects a common response to the campaign and the accusation that Lush was in some way hypocritical for discussing these abuses, as Lush would have to rely on police support in the event of a robbery or other such events. These responsibility and risk narratives sought to derail the discourse and divert the discussion from the issue at hand to a discussion of how the issue was being discussed. As the pressure placed on the state and police reduced, the debates became diffuse and unfocussed.

Confusion Narratives

A number of articles expressed confusion over the fact that a high-street cosmetics firm had engaged in such a stridently political campaign. These articles frequently used the terms ‘bizarre’, ‘ridiculous’ and ‘crazy’ in their descriptions of the campaign. Some of the negative articles suggested that due to its status as a private business, Lush had no right to comment on such cases and was intervening in matters it should not. For example, in an opinion piece, entitled ‘Lush’s moronic #Spycops campaign is a new low for brand purpose’, Ritson (2010) wrote: ‘you [Lush] sell soap, for fucks sake, what makes you think that elevates you to the position of starting a public campaign against the police?’.

The theme of confusion is evidenced in a number of other articles, including ‘Cosmetics chain Lush faces calls for boycott as bizarre advertising campaign accuses police of “lying” and “spying” and says they've “crossed the line”’ (Riley 2018), ‘Lush UK police campaign: Cosmetics giant blasted over bizarre “spycops” advertising’ (Powell 2018), ‘Lush accuse police of being spies and liars in bizarre marketing campaign’ (Olsen, Metro 1 June 2018) and ‘What do bath bombs have to do with undercover police? PR chief blasts Lush #spycops campaign’ (Harrington 2018). A sympathetic article published on the website of fashion magazine Elle (Hall 2018), entitled ‘Everything you need to know about Lush’s crazy controversial #spycops campaign’, reinforced the theme of confusion in its headline. In the body of the article, it argued that ‘Lush has been a highly political company since its inception ... So while the move to raise awareness around Spycops may appear peculiar at first glance, it actually tracks for a brand like Lush’.

Such narratives benefited the state’s hegemonic position in the discourse surrounding undercover policing. By positioning Lush’s support for victims and condemnation of the human rights abuses perpetrated by spycops as bizarre, the campaign was able to be more easily dismissed. Further, such narratives clouded the debate and decentred the narratives of the victims, once again moving the discussion away from the harm that was perpetrated and the search for justice to discussions about which organisations should have a say on such matters and whether or not it was appropriate for a high-street firm to take such a stance. In this sense, these confusion narratives contributed to the process by which the debates on spycops were diverted.

Conclusion

As this article showed, in the immediate aftermath of the Lush spycops campaign, media narratives tended to reinforce the problematic ‘rotten apple’ narrative surrounding the case. In addition to disguising the systemic problems and allowing these cases to be understood as the result of rogue individuals, this also detracted from efforts towards systemic change. The ‘rotten apple’ narrative predominantly emanated from state actors and was then foregrounded in the media’s reporting and framing of the case. In addition to narratives that emphasised the irresponsibility of the campaign and narratives that expressed confusion in relation to the campaign, the ‘rotten apple’ narrative diverted discussions away from the focus on the harm experienced by spied-on activists and instead focused discussions on and gave primacy to the ‘hurt feelings’ of ‘innocent’, ‘hard-working’, ‘front line’ police officers.

In addition to contributing to academic research on the spycops case, the data presented in this article show how ‘rotten apple’ explanations came to dominate the media’s reporting of police misconduct more generally and contributed to critical media studies literature on the role of the media in manufacturing consent for mainstream ideologies and systems of domination (Almiron, Cole and Freeman 2018; Cammaerts 2015). Notably, even positive reporting of the Lush campaign had a tendency to disguise and obscure the role of the state in the suppression and criminalisation of legitimate activism, potentially contributing to the suggestion that this scandal was a result of ‘rotten apples’. Further, Lush’s clarification appeared to accept the premise of the criticism that the campaign had ‘tarred all police with the same brush’. This framing sat comfortably within an emerging narrative that pitted a small number of ‘rotten apple’ spycops against a majority of ‘hard-working officers’. Ultimately, this framing failed to foreground issues of systemic police practice (e.g., institutional sexism). Activists, campaigners and core participants currently involved in the UCPI demand that the systemic issues that allowed over 1,000 groups to be spied on between 1968 and 2011 be acknowledged and addressed (Schlembach 2016). Nevertheless, the Lush campaign appears to have had positive outcomes and succeeded in its stated aim of raising awareness of the spycops scandal on behalf of activists.

As this article showed, the media plays an important role in shaping the success of inquiries relating to police misconduct. The ongoing UCPI was set up to ascertain the truth about undercover policing across England and Wales. The institutional dimensions to the harm perpetrated by undercover officers against activists cannot be addressed or understood through the prism of ‘rotten apple’ explanations of police misconduct. Thus, the success of the UCPI depends on it being willing and able to ask and investigate these bigger, more difficult, systemic questions. Despite activists and core participants having made their concerns about the systemic dimensions of the case clear, media reporting, in this instance, foregrounded ‘rotten apple’ explanations emanating from the establishment, to the detriment of those impacted.

Alibhai Z (2018) Lush’s #SPYCOPS campaign returns after being suspended due to ‘aggressive behaviour’ towards staff. iNews, 13 June. https://inews.co.uk/news/uk/lush-spycops-campaign-returns-282516

Almiron N, Cole M and Freeman C (2018) Critical animal and media studies: Expanding the understanding of oppression in communication research. European Journal of Communication 33(4): 367–380. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0267323118763937

Apple E (2019) Political policing in the UK: A personal perspective. In Choudry, A. (ed.) Activists and the Surveillance State: Learning from Repression: 177-196. London: Pluto Press.

Asfal N (2018) I don’t like Lush’s #spycops campaign, but shutting it down is an abuse of power. The Guardian, 4 June. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/jun/04/lush-spycops-campaign-off-duty-police

Barlow J (2018) Cosmetics store Lush slammed for ‘absolutely ridiculous’ campaign. Nottingham Post, 1 June. https://www.nottinghampost.com/news/nottingham-news/cosmetics-store-lush-slammed-absolutely-1632963

Barton M (2018) Mike Barton: Innocent blamed in Lush ‘Paid to Lie’ campaign. Northern Echo, 12 June. https://www.thenorthernecho.co.uk/opinion/16284418.mike-barton-innocent-blamed-in-lush-paid-to-lie-campaign/

BBC (2018) Lush 'anti-spy cops' campaign criticized. BBC, 1 June. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-44330078

BJL (2018) Lush had the right idea, but wrong execution. BJL.com, 5 June. https://bjl.co.uk/news/lush-right-idea-wrong-execution/

Boyd J (2018) The Lush #SpyCops campaign: Breaking through the backlash. Brandwatch, 22 June. https://www.brandwatch.com/blog/lush-spycops-campaign/

Brophy A (2018) How will Lush’s 'anti spy cops' campaign play with its target audience? YouGov, 27 June. https://yougov.co.uk/topics/consumer/articles-reports/2018/06/27/how-will-lushs-anti-spy-cops-campaign-play-its-tar

Brown M (2007) Holding judgement. The Sydney Morning Herald. 9 June. https://www.smh.com.au/national/holding-judgement-20070609-gdqchf.html

Burrell I and Peachey P (2012) How the press ignored the Lawrence story—Then used it to change Britain. Independent, 4 January. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/media/press/how-the-press-ignored-the-lawrence-story-then-used-it-to-change-britain-6284645.html

Cammaerts B (2015) Neoliberalism and the post-hegemonic war of position: the dialectic between invisibility and visibilities. European Journal of Communication 30(5): 522–538. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0267323115597847

Campaign Opposing Police Surveillance (COPS) (2019) Demo before public inquiry hearing. 20 March. http://campaignopposingpolicesurveillance.com/event/demo-before-public-inquiry-hearing-2/

Casciani D (2014) The undercover cop, his lover and their son. BBC News, 24 October. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-29743857

Chan J and Dixon D (2007) The politics of police reform: Ten years after the Royal Commission into the New South Wales Police Service. Criminology and Criminal Justice 7(4): 443–468. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1748895807082068

Choudry A (2019) Lessons learnt, lessons lost: Pedagogies of repression, thoughtcrime, and the sharp edge of state power. In Choudry, A. (ed.) Activists and the Surveillance State: Learning from Repression: 3-22. London: Pluto Press.

Dancey-Downs K (2018) Exposing the spy who loved me. Lush. https://uk.lush.com/article/exposing-spy-who-loved-me

Davies M (2018) Lush’s ‘paid to lie’ police campaign will do more harm than good for vulnerable women. Metro, 1 June. https://metro.co.uk/2018/06/01/lushs-paid-lie-police-campaign-will-harm-good-vulnerable-women-7597003/

Davies P, Francis P and Wyatt T (eds) (2014) Invisible Crimes and Social Harms. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

De Peyer R (2018) Home Secretary Sajid Javid launches scathing attack on Lush over ‘anti-police’ ad campaign. Evening Standard, 2 June. https://www.standard.co.uk/news/uk/home-secretary-sajid-javid-launches-scathing-attack-on-lush-over-antipolice-ad-campaign-a3853736.html

Ellefsen R (2016) Judicial opportunities and the death of SHAC: Legal repression along a cycle of contention. Social Movement Studies 15(5): 441–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2016.1185360

Evans R (2017a) Abandoned son of police spy sues Met for compensation. The Guardian, 4 December. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2017/dec/04/abandoned-son-of-police-spy-sues-met-for-compensation

Evans R (2018b) Cosmetics chain Lush resumes undercover police poster campaign. The Guardian, 13 June. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2018/jun/13/cosmetics-chain-lush-resumes-undercover-police-poster-campaign

Evans R (2018c) Campaigners stage walkout of ‘secretive’ police spying inquiry. The Guardian, 21 March. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2018/mar/21/campaigners-stage-walkout-of-secretive-police-spying-inquiry

Evans R (2018d) Met bosses knew of relationship deception by spy Mark Kennedy. The Guardian, 21 September. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2018/sep/21/met-bosses-knew-of-relationship-deception-by-police-spy-mark-kennedy

Evans S and Kitching C (2018) Serving policewoman’s brilliant response to Lush’s ‘anti-cop’ advertising campaign. Mirror Online, 5 June. https://www.mirror.co.uk/news/uk-news/i-am-indeed-paid-lie-12648399

Evans R and Lewis P (2013a) Police ‘smear’ campaign targeted Stephen Lawrence’s friends and family. The Guardian, 24 June. https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2013/jun/23/stephen-lawrence-undercover-police-smears

Evans R and Lewis P (2013b) Undercover: The true story of Britain’s secret police. London: Faber and Faber.

Fitzpatrick B (2016) #Spycops: Undercover policing, intimate relationships and the manufacture of consent by the state. In Ashford, C., A. Reed, and N. Wake (eds) Legal Perspectives on State Power: Consent and Control. Newcastle Upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Ghert-Zand R (2011) Lush soap brand boycotted for ties to pro-Palestinian group. Forward, 5 July. https://forward.com/schmooze/139445/lush-soap-brand-boycotted-for-ties-to-pro-palestin/

Greer C and Reiner R (2012) Mediated mayhem: Media, crime and criminal justice. In Maguire, M. Morgan, R. and Reiner, R. (eds) The Oxford Handbook of Criminology: 245–278. Fifth Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hall S (1999) From Scarman to Stephen Lawrence. History Workshop Journal 48: 187–197. https://doi.org/10.1093/hwj/1999.48.187

Hall C (2018) Everything you need to know about Lush’s crazy controversial #Spycops campaign. Elle, 6 June. https://www.elle.com/beauty/a21098901/spycop-lush-cosmetics-explainer/

Hall S, Critcher C, Jefferson T, Clarke J and Roberts B (1978) Policing the Crisis, London: Palgrave.

Harrington J (2018) What do bath bombs have to do with undercover police? PRWeek, 1 June. https://www.prweek.com/article/1466398/what-bath-bombs-undercover-police-pr-chiefs-blast-lush-spycops-campaign

Jackson W, Gilmore J and Monk H. (2018) Policing unacceptable protest in England and Wales: A case study of the policing of anti-fracking protests. Critical Social Policy, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261018317753087

Jones J (2018) Why We Need Lush’s Spycop Campaign, New Internationalist, 4 June. https://newint.org/features/web-exclusive/2018/06/04/spycops-lush-jenny-jones

Jones P J and Wardle C (2008) ‘No emotion, no sympathy’: The visual construction of Maxine Carr. Crime, Media, Culture 4(1): 53–71. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1741659007087271

Kaplan P (2009) Looking through the gaps: A critical approach to the LAPD’s rampart scandal. Social Justice 36(1): 61–81.

Lawrence D and McDonnell J (2018) As victims of spycops, we stand with Lush in campaign for full disclosure. The Guardian, 4 June. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2018/jun/04/as-victims-of-spycops-we-stand-with-lush-in-campaign-for-full-disclosure

Lersch K M and Mieczkowski T (2005) Violent police behavior: Past, present, and future research directions. Aggression and Violent Behavior 10: 552–568.

Loadenthal M (2014) When cops ‘go native’: Policing revolution through sexual infiltration and panopticonism. Critical Studies on Terrorism, 7(1): 24–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/17539153.2013.877670

Lovitz D (2010) Muzzling a movement: The effects of anti-terrorism law, money, and politics on animal activism, New York: Lantern Books

Lubbers E (2015) Undercover research: Corporate and police spying on activists. An introduction to activist intelligence as a new field of study. Surveillance and Society 13(3/4): 338–353.

Lush (2018a) Refugees welcome: Friendship fund update. https://www.lushusa.com/article_friendship-fund-update.html

Lush (2018b) #SpyCops statement. https://uk.lush.com/article/spycops-statement

MacPherson W (1999) The Stephen Lawrence inquiry. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/277111/4262.pdf

Mollen M (1994) Report of the Commission to investigate allegations of corruption and the anti-corruption procedures of the Police Department. New York: Mollen Commission.

Moore S (2014) Crime and the media. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan

Oslen M B (2018) Lush accuse police of being spies and liars in bizarre marketing campaign, Metro, 1 June. https://metro.co.uk/2018/06/01/lush-accuse-police-spies-liars-bizarre-marketing-campaign-7596440/.

Police Spies Out of Lives (2019) Institutional Sexism. https://policespiesoutoflives.org.uk/campaigns/institutional-sexism/

Potter W (2011) Green in the new red. San Francisco: City Lights Books

Powell T (2018) Lush UK police campaign: Cosmetics giant blasted over bizarre ‘spycops’ advertising. Evening Standard, 1 June. https://www.standard.co.uk/news/uk/cosmetics-giant-lush-blasted-over-bizarre-lying-police-campaign-a3853141.html

Punch M (2003) Rotten orchards: ‘Pestilence’. Police misconduct and system failure. Policing and Society 13(2): 171–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439460308026

Raab S (1993) New York’s Police allow corruption, Mollen panel says. New York Times, 29 December. https://www.nytimes.com/1993/12/29/nyregion/new-york-s-police-allow-corruption-mollen-panel-says.html?pagewanted=all&src=pm

Read C (2018) ‘Hang your heads in shame!’ Cosmetics giant Lush blasted for ‘anti-police’ campaign. Sunday Express, 2 June. https://www.express.co.uk/news/uk/968452/lush-cosmetics-high-street-anti-police-campaign-mark-constantine-rebecca-lush-savid-javid

Riley E (2018) Cosmetics chain Lush faces calls for boycott as bizarre advertising campaign accuses police of ‘lying’ and ‘spying’. Mail Online, 1 June. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-5794785/Cosmetics-chain-Lush-fire-bizarre-advertising-campaign.html

Ritson M (2018) Lush’s moronic #Spycops campaign is a new low for brand purpose. Marketing Watch, 5 June. https://www.marketingweek.com/mark-ritson-lush-spycops/

Rudgard O (2018) Police criticise Lush advertising campaign against undercover officers. Telegraph, 1 June. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2018/06/01/police-criticise-lush-advertising-campaign-against-undercover/

S and HAB (2018) Letters: ‘Spycop’ ex-wives: we support the Lush campaign. The Guardian, 6 June. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2018/jun/06/spycop-ex-wives-we-support-the-lush-campaign

Saner E (2018) How the Lush founders went from bath bombs to the spy cops row. The Guardian, 20 June. https://www.theguardian.com/media/2018/jun/20/lush-founders-from-bath-bombs-to-spy-cops-row

Schlembach R (2016) The Pitchford inquiry into undercover policing: Some lessons from the preliminary hearings. Papers from the British Criminology Conference, 16: 57–73. http://www.britsoccrim.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/pbcc_2016_Schlembach.pdf

Schlembach R (2018) Undercover policing and the spectre of ‘domestic extremism’: The covert surveillance of environmental activism in Britain. Social Movement Studies 17(5): 491–506. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2018.1480934

Scraton P (1987) Unreasonable Force: Policing, punishment and marginalisation. In Scraton, P. (ed) Law, Order and the Authoritarian State. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Sea Sheppard (2008) Lush and Sea Shepherd launch global anti-shark-finning campaign. https://web.archive.org/web/20081013124139/http://www.seashepherd.org/news/media_080903_1.html

Spalek B and O’Rawe M (2014) Researching counterterrorism: A critical perspective from the field in the light of allegations and findings of covert activities by undercover police officers. Critical Studies on Terrorism 7(1): 150–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/17539153.2013.847264

Stark R (1972) Police riots: Collective violence and law enforcement. Belmont: Wadsworth Publishing.

Stephens Griffin N (forthcoming) ‘Everyone was questioning everything’: Understanding the derailing impact of undercover policing on the lives of UK environmentalists. Social Movement Studies.

Taylor I, Walton P and Young J (1973) The new criminology: For a social theory of deviance. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Tombs S (2004) The ‘causes’ of corporate crime. Criminal Justice Matters 55: 34–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/09627250408553598

Wheaton O (2018) Lush remove #SpyCops posters from some shops after ‘intimidation from ex-police officers’. The Independent, 3 June. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/lush-spycops-posters-intimidation-police-undercover-officers-a8381531.html

Williams K (2010) Read all about it! A history of the British newspaper. London: Routledge.

Wood T (2016) Detainee abuse during op telic: A few rotten apples? Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Woodman C (2018a) Spycops in context: A brief history of political policing in Britain. London: Centre for Crime and Justice Studies. https://www.crimeandjustice.org.uk/sites/crimeandjustice.org.uk/files/Spycops%20in%20context%20%E2%80%93%20a%20brief%20history%20of%20political%20policing%20in%20Britain_0.pdf

Woodman C (2018b) Spycops in context: Counter-subversion, deep dissent and the logic of political policing. London: Centre for Crime and Justice Studies. https://www.crimeandjustice.org.uk/sites/crimeandjustice.org.uk/files/Spycops%20in%20context%20%E2%80%93%20counter-subversion%2C%20deep%20dissent%20and%20the%20logic%20of%20political%20policing.pdf

[1] ‘Spycops’ is a term that was widely adopted by activists to describe the undercover police officers who spied on them. This term was also adopted by Lush in their campaign (Lush 2018b).

[2] These were two of the most prominent public figures to have been spied on. Doreen Lawrence’s son, Stephen Lawrence, was killed in a racist hate-crime in London in 1993. John McDonnell is a prominent Socialist Member of Parliament in the UK and the former Labour Party Shadow-Chancellor.

[3] The term ‘middle-market tabloid’ is used to distinguish British newspapers, such as the Daily Mail and the Daily Express, from more traditional tabloid newspapers, such as The Sun. Middle-market tabloids are often viewed as a midway point between broadsheets and tabloids that focus on both serious news events and entertainment (Williams 2010). Jones and Wardle (2008) used the term ‘middle-market tabloid’ in their qualitative visual analysis of reporting on the Maxine Carr case.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/IntJlCrimJustSocDem/2020/57.html