Journal of Law, Information and Science

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Journal of Law, Information and Science |

|

Sheherezade and the 101 Data Privacy Laws:

Origins, Significance and Global Trajectories

GRAHAM GREENLEAF[*]

It is forty years since enactment of Sweden’s Data Act of 1973, the first comprehensive national data privacy law, and the first such national law to implement what we can now recognise as a basic set of data protection principles. This article answers the question, ‘How many countries now have data privacy laws?,’ starting by defining a ‘data privacy law’. The result is a global analysis of data privacy laws and the international agreements relevant to each, and of Data Protection Authorities and their interlocking associations.

The answer to the question — documented in the accompanying Table of global data privacy laws — is that, as of mid-2013, 99 countries have such laws, a number considerably higher than earlier commentators had assumed. By looking at the related questions of the date at which such laws were enacted, and the regions of the world in which they have arisen, we can see trends in development which indicate the future direction of global development of data privacy laws.

The article also analyses which international agreements or requirements concerning data privacy (OECD, EU, APEC, ECOWAS etc) affect which countries, and how many relevant parties have enacted laws in accordance with the various agreements or requirements. The extent to which data protection authorities (DPAs) are required as part of data privacy laws is analysed, and existing DPAs identified. The associations of DPAs in which each is involved are also identified, and the implications of their overlapping but incomplete memberships.

The conclusion reached is that, given the continuing accelerating growth in the number of such laws, it seems likely that, within a decade, data privacy laws will be ubiquitous in that they will be found in almost all economically more significant countries, and most others. This conclusion is supported by the number of official data privacy Bills currently before legislatures or under government consideration in at least 20 more countries. It is reinforced by the increasing importance of both international agreements and associations of DPAs.

A Postscript reveals that there are now 101 laws, not 99, and Sheherezade can rest a while.

Sheherezade told Sultan Shahryar yet another fabulous tale from a far-off land, but the Sultan was never satisfied, so each night Sheherezade brought him another tale (and thus saved her head), until one thousand nights had passed, and then one.[1] Like the thousand-and-one nights, the global history of data privacy laws is a tale that grows with each successive telling, and it may be that the steady growth of such laws in far-off lands will turn out to be the secret of the survival of privacy in a rather hostile world. The meme of data privacy, having escaped from the bottle over 40 years ago, is proving difficult to put back in.[2] It is not a history that can boast 1001 data privacy laws, but it does have 101, to which (dear reader) we shall now turn.

It is forty years since Sweden’s Data Act 1973 was the first comprehensive national data privacy law, and the first such national law to implement what we can now recognise as a basic set of data protection principles.[3] ‘How many countries now have data protection laws?’ seemed like a fairly straightforward question when it was asked of me in June 2011.[4] The usual answer, including mine, was somewhat vague: ‘about sixty’ or perhaps a well-informed respondent might have said ‘more than sixty’.[5]

No resources could be found to give a convenient and convincing answer,[6] leading to successive attempts to provide such an answer, of which this is the third over two years. The first[7] showed that at least 76 countries had enacted data privacy laws by mid-2011. Six months later, new laws and further investigation showed there were at least 89 countries with such laws.[8] The last 18 months have seen a moderate expansion in global data privacy laws. Since the previous analysis listing 89 countries, there have been new data privacy laws enacted covering the private sector in Ghana, Georgia[9], Nicaragua, the Philippines, and Singapore (private sector only). To the list must also be added laws omitted previously from Kosovo and Greenland (a Danish territory which is still subject to Denmark’s old data protection law). That brings the total to 96. However, as discussed below, there are also at least three data privacy laws,[10] both new and pre-existing, concerning the public sector only (Yemen, Zimbabwe and Nepal), which need to be added, bringing the total to 99.

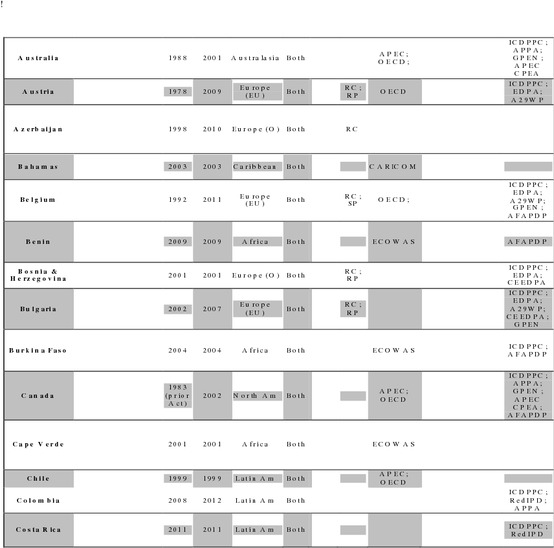

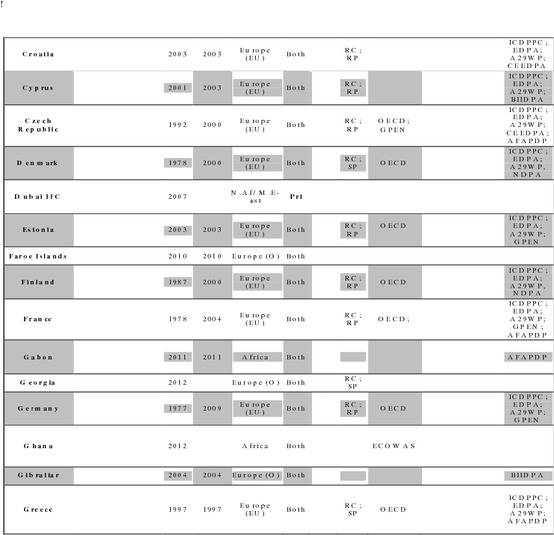

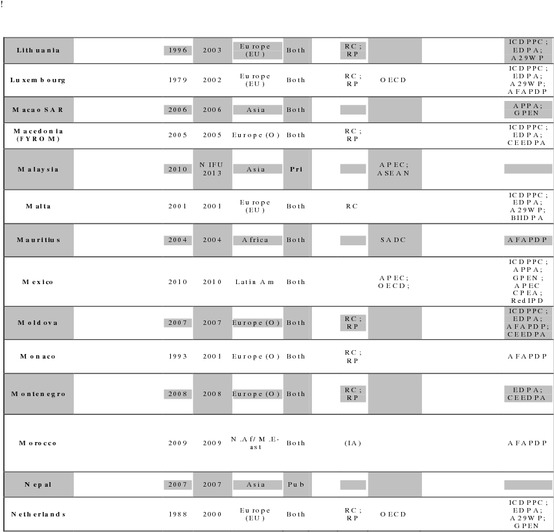

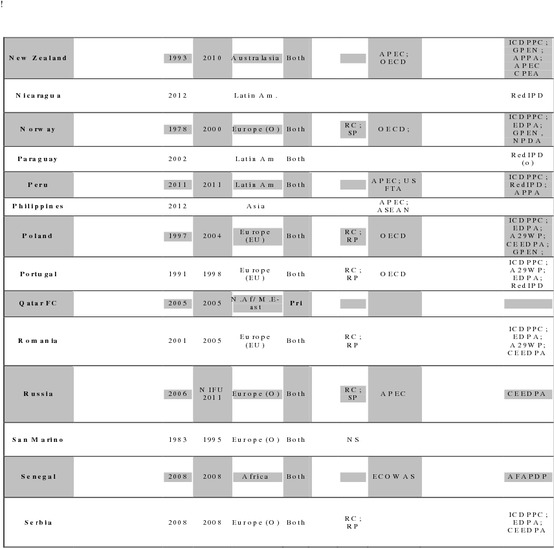

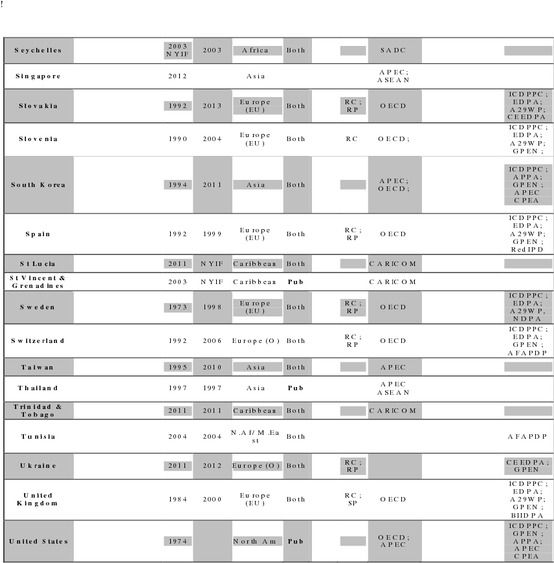

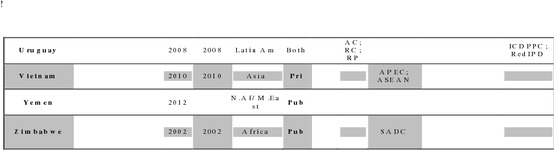

The Table of Data Privacy Laws at the conclusion of this article lists all countries (including otherwise independent legal jurisdictions) which have enacted data privacy laws; the principal law; when enacted; its sectoral coverage (only private sector; only public sector; or both sectors); the international data privacy commitments of the country, or the international recognition its laws have received; whether it has a data protection authority (named if so); and the international associations in which that DPA is involved. A separate Table of Official Bills lists known official Bills not yet enacted. The picture that will emerge from the analysis of the growth of these laws over time is that data privacy laws are spreading globally, and their number and geographical diversity accelerating since 2000. Growth of data privacy laws is not yet ‘flattening off’.

The number, growth and geographical distribution of data protection laws is significant. As Bennett and Raab said in their leading text in 2006, ‘over the past thirty or more years, comprehensive and general data protection laws have been regarded as essential tools for regulating the use of personal data’.[11] By tracking their occurrence we can obtain insights into the global progress of protection of data privacy as a human right, into the extent to which certain practices are becoming entrenched in the world’s legal systems (and therefore increasingly difficult to remove), and into the likely future rate of occurrence of new data protection laws in other countries. These matters affect the global geo-politics of privacy protection. Such information is also significant for more academic enquires, such as into the extent (and success) of data protection laws as a ‘transplant’ into legal cultures in which it was not previously found.

Before answering a simple question, it is sometimes necessary to answer some more complex questions first. In this case, before starting to count data privacy laws it is necessary to answer: What is a country?; What is a law?; What scope must a law have?; What data privacy principles must a law include?; and how effective must a law be? The overall approach taken here is to attempt to define what are the minimum criteria that reasonable and impartial observers could agree constitute a ‘data privacy law’ or ‘data protection law’ when satisfied. The factors are used to determine which countries’ laws are included in the concluding Tables.

In this analysis, ‘countries’ is a slight exaggeration, and a more accurate term would be ‘separate legal jurisdictions’. The Table includes the two Special Administrative Regions (SARs) which have constitutionally different legal systems from the rest of China (Hong Kong and Macao, under the principle of ‘One Country, Two Systems’) and five British dependent territories which have their own legal systems (the Isle of Man, Jersey, Guernsey, Gibraltar and the Bahamas). By the same reasoning it includes the Qatar Financial Centre (QFC) and the Dubai International Finance Centre (DIFC), because these areas, somewhat similar to ‘special economic zones’, have data privacy laws which apply to all business carried out within the QFC and DIFC, and their own administrations, data protection authorities and courts to enforce such laws. Geographically, they may be like miniature versions of Hong Kong, but the size of a jurisdiction is little indication of how much personal data may be processed within it or transferred to or from it, so it seems best to include them for completeness. Whatever view one takes of Taiwan as a country, it is also included, as is Greenland (a Danish territory with a separate data privacy law).

However, sub-national jurisdictions which do not have their own separate legal systems, or are subject to the laws of a federation in relation to data privacy law, are not included. So states and provinces in Germany, Canada, Australia, Spain, Switzerland and elsewhere with data privacy laws are excluded even if they do sometimes provide some non-comprehensive coverage of the private sector as well as covering the public sector.[12] Certain provinces of the People’s Republic of China which have enacted local laws, are excluded for similar reasons. State or provincial laws which only cover the local public sector, are also excluded. Many of these sub-national laws are quite significant sources of data privacy legislation and case law, or were pioneers in data protection. Hesse in Germany, Quebec, Ontario and British Columbia in Canada, and Victoria and New South Wales in Australia are examples. It would be valuable to include such jurisdictions in a separate Table, but this has not been done in this article. The result of this conservative approach is that no country is included twice in the Table, but nor is any jurisdiction unreasonably excluded.

The approach taken here is that a ‘law’ is what the word implies, and this is not satisfied by a voluntary code of conduct or a trustmark scheme. A law must set out data privacy principles (which ones are discussed later) in a specific fashion, not only as a general constitutional protection for privacy, or a civil action (tort) for infringement of privacy.

A law in this sense must make its data privacy principles enforceable, but whether this is by criminal offences, civil penalties, administrative orders for compensation, or a right of civil actions before the courts, is left open, as it was (for example) in the original Council of Europe Convention. Most jurisdictions with data privacy laws also have a Data Protection Authority (DPA), a separate institution which has responsibility for the data privacy legislation, but this is not a necessary requirement and is was left open in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and Council of Europe in 1981.

2.3 What scope must a law have?

Nearly ninety per cent of all data privacy laws in the Table (88/99) cover both the public sector and the private sector of a country, but there are two small groups of exceptions that only cover one or the other sector, and they are both included.

In relation to the private sector, to be included a law must cover most economically significant aspects of the operation of the private sector. This excludes countries which have only scattered sectoral privacy laws (eg credit reporting or medical records laws). The USA, which has numerous limited sectoral laws in the private sector is included not because of its private sector laws, but only because of its federal public sector law. Many countries have some exceptions in their private sector coverage, such as various forms of ‘small business’ exceptions (eg Japan and Australia), or exceptions for non-automated records, or exceptions for the media (many countries), or for employment records (Australia again). Such exceptions are not a basis for exclusion. A law with ‘largely comprehensive private sector coverage’ is considered as covering that sector.

There is a small but growing group of countries (six at present), particularly in Asia, with laws which only cover the private sector but provide no protection in relation to the public sector: Singapore, Malaysia, Vietnam, India, Qatar Financial Centre and Dubai International Finance Centre.

However, most jurisdictions which have laws with private sector coverage, also have data privacy laws which cover their national public sectors (88/94). Such protection is sometimes by different legislation from that covering the private sector. Where there is a different law for the public sector it will often have principles and enforcement mechanisms which differ significantly from those applying to the private sector. Some jurisdictions which now have private sector coverage initially only covered their public sectors, including the OECD members, Australia, Japan, Canada and South Korea, with private sector coverage only introduced up to 15 years later.[13] At least six jurisdictions provide basic data privacy protection in relation to their public sector only (the United States, Thailand, Yemen, Zimbabwe, St Vincent & the Grenadines, and Nepal), but do not do so for their private sector according to the criteria used here. As a federation, the US Privacy Act 1974 only covers the federal public sector, but some states have equivalent laws.[14] As unitary counties, the laws in the other countries cover their whole public sectors.

Are there other countries in this category? There are 94 countries that have right to information (RTI) laws (also called ‘freedom of information’ or FOI laws).[15] Of these 94 countries with RTI/FOI laws, 37 do not otherwise have data privacy laws.[16] While there are quite a few laws which go beyond only providing access rights, such as by providing rights of correction of personal information (eg the laws of Australia, China, the Cook Islands, Ethiopia, Jamaica and South Africa), and some provide rights of compensation for breaches of access rights, few go any further and provide other data privacy rights such as limits on collection, use and disclosure, data security requirements, or deletion/de-identification requirements. Of these 37 laws, an analysis of the 25 available in English shows that only four of them could also be considered to meet a minimum set of conditions to qualify as a data privacy law for the public sector: the laws of Yemen, Zimbabwe, Nepal and Thailand. The remaining 12 laws[17] (seven in Spanish, five in other languages) could contain additional public sector data privacy laws, and while this does not seem likely, it has not yet been conclusively assessed.[18] New RTI/FOI laws are being enacted every year, so it is necessary when assessing the global dissemination of data privacy laws to also keep these new RTI/FOI laws in mind. The Table does not include any countries which might have public sector privacy laws for some of their regional governments only (China might qualify if it did).

2.4 What data privacy principles must a law include?

Standard texts on data privacy do not often define the minimum set of principles which a law must contain to be considered a data privacy law, but some go close to so doing. Bennett and Raab in 2006 refer to a ‘strong consensus’ that has emerged as to what are a set of twelve ‘fair information principles’ (FIPs),[19] which can be summarised as: accountability; purpose identification; collection with knowledge and consent; limited collection to where necessary for purpose (also called ‘minimal collection’); use limited to identified purpose or with consent (finality); disclosure likewise; retention only as long as necessary; data kept accurate, complete and up-to-date (often called ‘data quality’); security safeguards; openness on policies and practices; individual access; individual correction. When they discuss data protection legislation, they at one point refer to the ‘universal embodiment’ of these twelve FIPs ‘in national and sub-national laws, in the European Union (EU) Directive, and then in legislation passed subsequent to that’.[20] However, over the following pages they are more realistic and note that some FIPs, such as the data quality principles finality principles are only included in ‘most’ laws.[21]

Bygrave in 2003 also comes close to providing a set of necessary requirements when he ‘provides an overview of the basic principles applied by data processing laws to the processing of personal data’.[22] He then discusses ‘fair and lawful processing’, ‘minimality’, ‘purpose specification’, ‘information quality’, ‘data subject participation and control’, disclosure limitation’, ‘information security’ and ‘sensitivity’.[23] Other than ‘sensitivity’ these categories are close to the FIPs of Bennett and Raab, but do not include all of them. Neither Bennett and Raab, or Bygrave attempt to state a minimum set of principles that should be included in a data privacy law, but imply that most of the principles in their lists should be included.

Another approach is to start with the two earliest international instruments concerning data privacy, the OECD privacy Guidelines of 1981 and the Council of Europe (CoE) Data Protection Convention 108 of 1981 (‘Convention 108’) (without its 2001 Additional Protocol). It is reasonable to regard them as providing the best guide to the minimum requirements of a data privacy law, given that they existed for more than twenty years prior to the analysis of both Bennett and Raab and Bygrave. That is the approach taken in this article. The principles in those earliest two instruments can most simply be summarised as the following 10 principles:

1. Data quality – relevant, accurate, & up-to-date.

2. Collection – limited, lawful & fair; with consent or knowledge.

3. Purpose specification at time of collection.

4. [Notice of purpose and rights at time of collection (implied)].

5. Uses & disclosures limited to purposes specified or compatible.

6. Security through reasonable safeguards.

7. Openness re personal data practices.

8. Access – individual right of access.

9. Correction – individual right of correction.

10. Accountable – data controller with task of compliance.

Principles concerning minimal collection, retention limits and sensitive information are not included, as they only became common requirements later, and the aim here is to identify a basic set of data privacy principles with some pedigree in international agreements and academic scholarship.

However, the question still arises whether a data privacy law must include every aspect of the content principles of these two instruments? What may be expressed as a single principle in these instruments may compact two logically distinct principles, for example the use and disclosure limitation principles, and the data subject’s rights of access and correction. The following Table breaks down the OECD and CoE content principles into 15 separate principles, and then states whether those principles can be found in the laws of the 10 countries in Asia which could be regarded as having data privacy laws (for Thailand a Bill only). These are a very diverse range of countries, with influences on data protection laws coming from many sources, and so would seem to provide a reasonable (and manageable) test set to assist a decision on the content of a data privacy law.

|

Jurisdictions[24]

|

HK

|

IN

|

JN

|

KR

|

MA

|

MY

|

PH

|

TW

|

SN

|

VN

|

TTL

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Collection ‘limits’ (‘not excessive’)

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

9

|

|

Collection by lawful means

|

0

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

7

|

|

Collection by fair means

|

0

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

7

|

|

Purpose of collection ‘specified’ by time of collection

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

9

|

|

Collection with knowledge or consent, when from data subject

|

0

|

0

|

?

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

9

|

|

Data quality – relevant, accurate, complete & up-to-date

|

0

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

9

|

|

Uses limited to purpose of collection, with consent or by law

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

10

|

|

Disclosure limited to collection purpose, with consent or by law (or

stricter)

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

10

|

|

Secondary uses and disclosures only allowed if compatible (or

stricter)

|

0

|

0

|

0[25]

|

0

|

0

|

X[26]

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

9

|

|

Secondary purpose ‘specified’ at change of use (or

stricter)

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

?

|

0

|

X

|

7

|

|

Security safeguards[27] –

‘reasonable’

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

10

|

|

Openness re policies on personal data

|

0

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

6

|

|

Access to individual personal data

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

10

|

|

Correction of individual data

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

10

|

|

Accountable data controller

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

10

|

|

Total for OECD/CoE principles /15

|

14

|

11

|

14

|

15

|

15

|

11

|

13

|

15

|

15

|

11

|

Av 13.4

|

Table: OECD & CoE108 ‘content’ principles, as found in laws of 10 Asian jurisdictions (‘O’ indicates element is found in the law, ‘X’ indicates it is absent).

While some countries do satisfy all 15 criteria (South Korea, Macau, Singapore and Taiwan), the average is 13.4 principles over the 10 countries. It would be too strict to require all 15. For example, there is no explicit ‘openness’ principle in six of the 10 laws, and only five of the 15 are satisfied by all 10 countries (use and disclosure limitations, security requirements, and data subject access and correction rights). None fall below satisfying 11 of the 15. While the selection of countries is not geographically representative, and analysis of their laws should not determine any conclusions, the results found nevertheless seem congruent with an informed intuitive approach as to what a data privacy law should contain as a minimum.

Therefore, the assumption on which the following analysis of global privacy laws is based is that a data privacy law must include as a minimum (i) access and correction rights (‘individual participation’), (ii) some ‘finality’ principles (limits on use and disclosure based on the purpose of collection), (iii) some security protections; and (iv) overall, at least 11 of the 15 OECD/CoE principles identified above.

Any such analysis will necessarily include some subjective judgments at the margin of acceptability. In the above example, the inclusion of both India and Vietnam is based on generous interpretations of their laws (in the absence of any cases to negative such interpretations). The Indian law is replete with ambiguities, including questions such as whether all or only some principles apply to protect data subjects when data is received from a third party rather than from the data subject. In relation to Vietnam, the principle of subject access is not explicit and must be implied from the right of correction in what are very short statements of sets of data privacy rights in two pieces of legislation. It is also necessary to conclude that two laws, one dealing with e-commerce and one with consumer rights, effectively cover ‘the majority of private sector personal data’.

Many countries have laws covering parts of their private sector (eg credit reporting, e-commerce or medical records), or requiring their private sectors to comply with a particular data protection principle (eg aspects of data security), but these do not meet the criteria for this study and the Table. Recent examples are from Indonesia and Turkey (both concerning e-commerce). Other examples are the many sectoral privacy laws in the USA which deal with parts of the US private sector.[28] Nor do US private sector privacy laws meet the criteria even if aggregated,[29] and possibly they could not do so for constitutional reasons.[30]

2.5 How effective must a law be?

This analysis only considers whether a data privacy law exists on paper (ie has been enacted) and is in force. The assessment of how effectively a law is enforced is half of the task of an EU ‘adequacy’ assessment, and in each instance such an assessment takes many weeks of work.[31] Apart from being impossible for 98 countries, that is not the purpose of this analysis. While each reader may have their own list of countries which they would suspect as being very probably at the low end of enforcement effectiveness, depending on what we know about them. In fact reliable information about enforcement of most data privacy laws is difficult to obtain, and evaluation of impact extremely difficult.[32] Also, the fact that such countries have data privacy laws in force leaves open the possibility that enforcement arrangements can change very quickly toward effectiveness. Laws are not ruled out, therefore, for lack of evidence of effectiveness. That is a different enquiry from this.

Finally, for the purposes of this brief overview, it is important to note that ‘growth’ or ‘expansion’ of data privacy laws cannot be equated with improvement in privacy protection. Some privacy laws are simply not enforced. Surveillance activities in both the private and public sectors can also grow at the same time as laws are enacted and operational, and quite often do when data privacy laws are a trade-off for, or a belated response to, more intensive surveillance. Assessing the effectiveness or value of data privacy laws is a far more complex task than is undertaken in this relatively simple exercise.

2.6 The resulting global tabulation

To summarise the above discussion, in this article and the accompanying Table, a country (including any independent legal jurisdiction) is considered to have a ‘data privacy law’ if it has one or more laws covering the most important parts of its private sector, or its national public sector, or both, and that law provides a set of basic data privacy principles, to a standard at least approximating the minimum provided for by the OECD Guidelines or Council of Europe Convention 108, plus some methods of officially-backed enforcement (ie not only self-regulation). To approximate the OECD/CoE standards, a law must provide individual participation, finality, security and at least 11 of the 15 principles overall.

Using this definition of a country with a data privacy law, the annexed Table of Data Privacy Laws applies the definition to determine that 99 countries currently have such laws, and lists them alphabetically. What can analysis of this Table tell us about how these laws have developed globally over the last 40 years since Sweden was the sole national experiment in 1973? The most obvious questions are to ask at what rate this expansion has occurred, and where has it occurred? Answers to these questions will enable some informed discussion of the likely rate and location of future global growth in data privacy laws, and its implications.

3.1 Countries without data privacy laws: Heading toward a minority

A tabulation of countries with data privacy laws requires the complement to be determined: how many countries have no such laws? There are at least 109 countries with no laws yet enacted, taking into account UN member states and a number of non-member states.[33] If the 20 current Bills known are taken into account (the Thai Bill is ignored because there is already a public sector Act), there are 89 countries[34] with no Acts or Bills. The global distribution of 208 countries is therefore: 89 with no Acts or Bills; 20 with Bills; 99 with Acts. It is clear from the list of countries with Bills that the numbers could change quite soon. Enactment of six more Bills will put the number of countries with data privacy laws in the majority. This is likely to occur in 2014. Of course, numbers of countries with laws is not the only indicator of significance, and other measures based on the populations or economic significance of countries could be used.

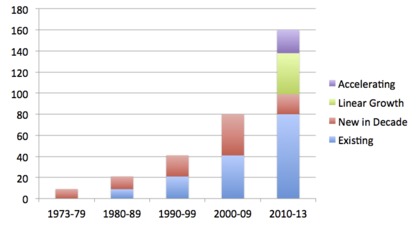

The rate of expansion has averaged approximately 2.5 laws per year for 40 years, but it has not been a linear growth. The number of new data privacy laws globally, viewed by decade, has grown as follows: 9 (1970s), +12 (1980s), +20 (1990s), +39 (2000s) and +19 (3.5 years of the 2010s), giving the total of 99.

In the 1970s, data privacy laws were a western European phenomenon (Austria, Denmark, Greenland, Germany, France, Norway, Sweden, and Luxembourg), other than for the US public sector Act. The position was similar in the 1980s (Finland, Iceland, Ireland, the Netherlands, San Marino, the UK, and three territories related to the UK), with Israel as the first non-European state in 1981, and Australia, Canada and Japan providing ‘public sector only’ legislation. Acceleration commenced in the 1990s, as most remaining western European countries (EU and EEA) enacted laws (Belgium, Italy, Greece, Monaco, Portugal, Spain, and Switzerland), with developments in Portugal and Spain in conjunction with democratisation. More significantly, with the collapse of the Soviet Union many former ‘eastern bloc’ countries enacted data privacy laws as part of their protection of civil liberties (Albania, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia), and the first ex-Soviet-republics (Azerbaijan and Lithuania) did likewise. The spread outside Europe also started, with the first laws in Latin America (Chile) and the first comprehensive laws in the Asia-Pacific (Hong Kong, New Zealand and (with limitations) Taiwan, plus Thailand and South Korea’s public sector laws), also often related to increased democratisation.

In the 2000s the acceleration continued, and increased in almost all regions of the world. Most striking was the expansion in the former eastern bloc and Soviet republic countries the (Bosnia & Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Estonia, Latvia, Macedonia (FYROM), Moldova, Romania, Serbia and Montenegro, plus Russia itself, though not in force until 2011), plus the addition of the remaining western European countries (Andorra, Cyprus, Gibraltar, Liechtenstein and Malta). Outside Europe, expansion accelerated in the Asia-Pacific (Macao SAR, and Nepal’s public sector, and private sector extensions of existing laws in Australia, South Korea, and Japan), Latin America (Argentina, Colombia, Paraguay and Uruguay), and the Caribbean (Bahamas, St Vincent & Grenadines). Rapid development took place in Africa with new laws in Tunisia and Morocco (North Africa) and Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, Mauritius, Senegal, Seychelles, and Zimbabwe’s public sector law (sub-Saharan Africa). The Kyrgyz Republic became the first country in Central Asia to legislate in 2008, and the Dubai and Qatar Financial Centres added the first laws in the Middle East. The ‘noughties’ (2000-09) was the first decade in which non-European expansion of laws (23) exceeded that in Europe (16).

In the first three and a half years of this decade 19 new laws have been enacted. All remaining European countries enacted laws (Faroe Islands, Georgia, Kosovo and Ukraine), with the exception of Turkey (also the only remaining OECD exception) and the two non-members of the Council of Europe (Belarus and the Vatican). The Russian law also finally came into force. Outside Europe, almost all regions have already shown continuing expansion. Expansion outside Europe (15) continues to outstrip that within Europe (3), and this will of necessity continue as the capacity for European expansion is now largely exhausted. Growth comes from all regions: India, the Philippines, Malaysia, Vietnam, and Singapore (the last three only private sector) (Asia); Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Mexico and Peru (Latin America); Angola, Gabon, and Ghana, (Africa); St Lucia and Trinidad & Tobago, (Caribbean); and Yemen (public sector) (Middle East). So far, the 2010s are the most intensive period of data protection development in the 40-year history of the field, averaging more than five new laws per year.

There is also a continuing strengthening of existing law outside Europe in the 2010s, as has occurred in Hong Kong, South Korea, Australia, and Taiwan, to consider only the Asia-Pacific.

Geographically,[35] more than half (53 per cent) of data privacy laws are still in European countries (52/98), EU member states making up less than one third (28/98), even with the expansion of the EU into Eastern Europe. There are data privacy laws in all 28 member states of the European Union (counting Croatia as of 1 July 2013), and a further 24 laws in other European countries or jurisdictions (including the EEA states). Only a few European countries remain without such laws, (Belarus, the Holy See/Vatican, and Turkey). There are nine laws in Latin America. In the Americas, are also the laws in Canada and the USA, and four laws in the Caribbean. In Asia there are now 12 of 27 countries with data privacy laws. Both Australia and New Zealand have data privacy laws, but no countries in the Pacific Islands do so (the only region with no such laws). In North Africa and the Middle East, there are six such laws, and 10 in Sub-Saharan Africa. The French-speaking Association of Personal Data Protection Authorities (AFAPDP), and France’s CNIL have both made efforts to encourage expansion of data privacy in African francophone countries. The Kyrgyz Republic law is the first in Central Asia, though Mongolia’s laws also come close to qualifying.

The geographical distribution of the 99 laws by region is therefore: EU (28); Other European (25); Asia (12); Latin America (9); (sub-Saharan) Africa (10); North Africa/Middle East (6); Caribbean (4); North America (2); Australasia (2); Central Asia (1); Pacific Islands (0). So there are 44 data privacy laws outside Europe, 47 per cent of the total. Because there is little room for expansion within Europe, the majority of the world’s data privacy laws will soon be from outside Europe, probably by the middle of this decade.

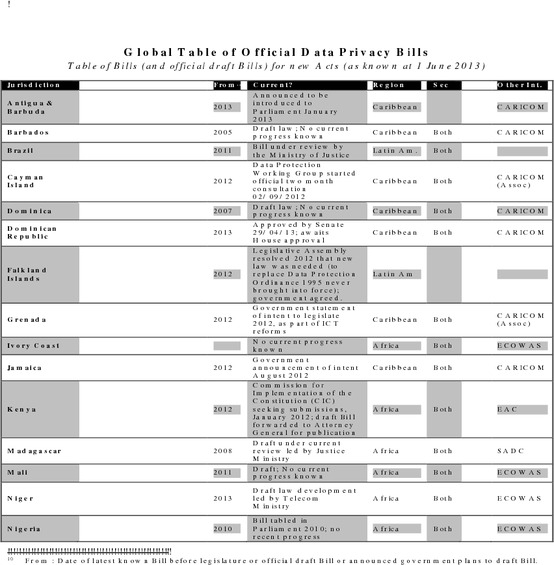

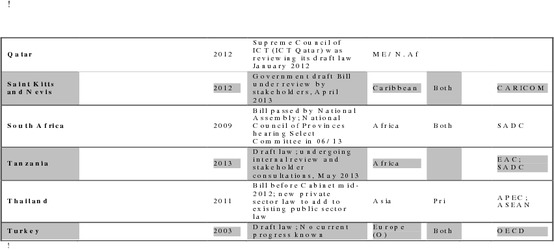

3.4 Bills for new Acts – Where will expansion occur next?

The annexed Global Table of Data Privacy Bills lists known official Bills for new Acts, both those which have been introduced into legislatures, and those which are under official consideration by governments. Information is included about the current known state of a Bill. Currently, there are 21 such Bills known, based on reliable sources. As shown in the Table they are primarily from the Caribbean (8) and Africa (8)[36], plus two from Latin America (Brazil and the Falkland Islands), and one each from the Middle East (Qatar, as distinct from the Qatar Financial Authority sub-region), Europe (Turkey) and Asia (Thai private sector). Further research may reveal more Bills under consideration but not yet listed. Some Bills are excluded because they have not been enacted for a decade after introduction,[37] and some are excluded because they appear to have been rejected by legislatures, not merely delayed.[38]

The Table does not include Bills for revisions of existing Acts although these are important in expanding the strength of data privacy laws globally, as exemplified by legislation in the past two years in South Korea, Taiwan and Hong Kong.

3.5 Predicting growth and ubiquitous data privacy laws

For over two decades the rate of adoption of new data privacy laws per year has been steadily increasing, and the regions of the globe that have such laws has been steadily expanding. If the current rate of expansion for 2010-mid 2013 continues in a linear fashion, 50 new laws would result in this decade, bringing the total to 140. On the other hand, continued acceleration would make the total somewhere between 140 and 160 (ie 60 to 80 new laws this decade). Even on the conservative (and almost certainly unrealistic) assumption that the 2010s will see no more data privacy laws than the 2000s, there would be 130 countries with data privacy laws by the decade’s end, with a large majority of the laws by then coming from outside Europe.

Figure 1: Growth of data protection laws by decade (to June 2013), with projections to 2020 (linear = 139; accelerating – 160)

Even allowing for a few more legally distinct territories to be added, the total number of jurisdictions globally is about 210. By the end of this decade, the number of countries with data privacy laws, all of which have a strong ‘family resemblance’ will be somewhere between 130 and 160 on the estimates above, more likely toward the higher end. In other words, between 62 per cent and 76 per cent of all jurisdictions globally will have data privacy laws in only seven years time, and global growth can be expected to continue beyond 2020. Whatever country numbers and growth rates are used, it seems likely that at some year in the next decade the number of countries with data privacy laws will reach a ‘tipping point’ at which it becomes in the interests of all jurisdictions wishing to participate in the global economy to have such laws. It is not unrealistic to talk of ‘global ubiquity’ of data privacy laws within 50 years of the enactment of the first such national law in Sweden. ‘Ubiquity’ in this context means that almost all countries will have data privacy laws, and most of their neighbours will have them, even if there are still a few exceptions remaining.

There are other ways, potentially more useful, by which global expansion of data privacy laws could be measured, say by the populations of the countries concerned, or by their GNP, or GNP per head, or other measure of economic significance. These could show different trends, and would be valuable, but may not be necessary for the purposes of this research. Inspection of the list of 119 countries in the two Tables which already have data privacy laws or have official Bills, in comparison with the above-noted list of 89 that do not, makes it obvious that data privacy laws are found in almost all the world’s larger and more economically significant countries. If one adds Brazil, South Africa, Nigeria or Kenya from the list of countries with official Bills, the picture is even more clear. Two of the few economically highly significant countries in the list of countries with no laws or Bills are China and Indonesia. Indonesia has, in 2012, enacted a data privacy regulation for e-commerce and is reported to be drafting a comprehensive law.[39] China is enacting a mosaic of data privacy laws in economically significant sectors, but could move to a comprehensive data privacy law.[40] India has legislated, though poorly and idiosyncratically, and there is considerable internal and external pressure on India to enact more conventional comprehensive legislation. South Africa’s legislation has almost completed its passage, and Brazil’s may do so in 2013: another BRIC in the wall, we could say.

3.6 Enough on quantity! – What quality do these laws have?

Although an OECD/CoE ‘minimum standard’ has been used to define a ‘data privacy law’ (and inclusion in the Table), this should not lead to the mistaken assumption that only such a minimum standard of data protection is what is achieved be the laws from countries outside Europe.[41] Analysis of 33/39 countries outside Europe with data protection laws as at December 2010,[42] showed that in relation to 10 principles that were more strict than the OECD/CoE ‘basic principles’, the 33 non-European laws on average exhibited 7/10 of those principles. Some of these additional ‘European’ principles occurred in more than 75 per cent of the 33 countries assessed, namely ‘border-control’ data export restrictions (28/33); additional protection for sensitive data (28/33); deletion requirements (28/33); recourse to the courts (26/33); minimum collection (26/33); and specialist data protection agencies (25/33). The number of non-European laws has now expanded to 44, but the new laws seem to be at least as strong as in previous decades. In addition, many existing laws are being strengthened to keep up with rising expectations of privacy protection, international agreements, and the examples set by other countries (see the ‘Latest’ column in the Table). This is important, because the strength or quality of data privacy laws is rising globally, as well as their number.

International agreements concerning data protection have had a considerable influence on adoption of data privacy laws for 30 years since the drafting of both the OECD’s privacy Guidelines and the Council of Europe Data Protection Convention at the outset of the 1980s. Since then, Developing in part out of the Council of Europe data protection Convention, the European Union’s data protection Directive of 1995 has been the most influential international instrument, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) Supplementary Act on data protection has spurred data privacy laws in West Africa, and the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation’s (APEC) Privacy Framework has created regular opportunities for discussion of privacy issues among some Asia-Pacific jurisdictions.

To complete this global survey it is necessary to look at penetration of both international instruments dealing with data privacy, and international associations of data protection authorities. Analysis of the substance and significance of these instruments and associations is largely beyond the scope of this article, which aims more at analysis of which countries are affected by them.

All 28 member states of the European Union are required to have data privacy laws which implement the EU data protection Directives, and all do so (see the Table). Four additional countries have applied to join the EU,[43] and one of these (Turkey) does not yet have a data privacy law. The European Economic Area (EEA) includes the European Union member states plus Iceland, Norway and Liechtenstein, all of which have data privacy laws consistent with the Directive, resulting from the EEA Treaty. Steps to develop a Regulation to replace most aspects of the Directive, and increase the level of protection, are continuing.

Countries or jurisdictions outside the EEA can obtain from the European Commission a decision that their laws provide an ‘adequate’ level of protection of privacy, to enable free flow of personal data from EU member states to organisations in those countries.[44] As yet, the EC has only made such decisions in relation to twelve jurisdictions as a whole, a minority of which are of economic or political significance,[45] the most recent being Uruguay and New Zealand.

4.2 Council of Europe data protection Convention 108

With the recent new law in Georgia and ratification by Russia, forty-five of the forty-seven Council of Europe member states have now ratified the Council of Europe Convention 108, and have data privacy laws. Turkey has signed but not ratified the Convention and is now the only Council of Europe member state not to have enacted a data privacy law, following recent enactments by Armenia and Georgia. San Marino has not signed or ratified, but does have a law. Belarus is not a Council of Europe member because of human rights concerns, and the Vatican is not a member because it is not a democracy.

The Additional Protocol (‘ETS 181’) to the Convention also requires a commitment to data export restrictions and to an independent data protection authority, and brings the standards of the Convention up to approximately the same level as the Directive. Forty-three member states have signed the Additional Protocol (Georgia only in May 2013), and 33 have subsequently ratified it (plus Uruguay). Twelve countries that have ratified the Convention (plus three territories on whose behalf the UK acceded to the Convention) have not ratified the Additional Protocol. Where a Council of Europe member has ratified both Convention 108 and the Additional Protocol, it is extremely unlikely as a matter of practice that data exports to that country from EU member states would be prevented, so obtaining an adequacy finding under the Directive appears to be largely irrelevant in practice. This is noted in the Table.

Since 2008, the Council of Europe has made it clear that it wishes the Convention and Optional Protocol to become global agreements, and that it welcomes requests by states outside Europe with suitable data privacy laws to apply to accede to both. Uruguay was the first non-European state to be invited to do so, and in 2013 acceded to and ratified the Convention and the Additional Protocol.[46] The second ‘globalisation’ invitation was also issued to Morocco. The Convention is now in a process of ‘modernisation’ which if successful will incorporate both the existing Convention and the Optional Protocol.[47]

An adequacy finding from the EU does not impose any reciprocal obligations on the recipient to allow free flow of personal data from it to EU countries. This obligation does arise when countries outside the EU (including other European countries) become members of the Council of Europe Convention 108.

4.3 The OECD and its Guidelines

All of the 34 OECD member countries,[48] other than Turkey and the USA (in relation to the private sector), now have a data privacy law implementing the OECD’s privacy Guidelines of 1981. The OECD’s plans for enlargement[49] mean that more countries in future will be likely to be influenced by the OECD privacy Guidelines to adopt data privacy laws. The OECD is currently revising the Guidelines.

4.4 Regional agreements between countries

The following regional groupings of countries are all relevant to the development of data privacy laws (with the exceptions of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) and the Common Market of the South (Mercado Común del Sur) (MERCOSUR), and their memberships are therefore noted in the Tables. At present, the ECOWAS, APEC and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) groupings are probably the most significant, but the development of regional data privacy agreements is likely to play a more significant role on all continents in future.

Four fifths (17) of the 21 APEC member ‘economies’[50] do have data privacy laws in at least one of the two sectors (see the Table), but four do not (Brunei; Indonesia; China; and Papua New Guinea). Thailand and the USA have public sector only laws, and Malaysia and Vietnam have private sector only laws. Thailand has a Bill for a comprehensive laws being re-drafted for its Cabinet. Whether APEC will expand beyond 21 members is still possible, but unlike the EU, its membership currently seems frozen. Numerous countries have been trying to join for some time, without success.[51] APEC membership and the APEC Privacy Framework means little more than voluntary participation in six monthly discussions of APEC’s data privacy sub-group (useful though that is). APEC’s Cross-Border Privacy Rules (CBPR) does not yet have any members fully operational with an endorsed Accountability Agent, so involvement in it is not yet noted in the Table.

Possibly more influential than APEC in encouraging new privacy laws is ASEAN, a 10 nation[52] treaty-based organisation which has a policy to improve its members’ data protection by 2015. Singapore, the Philippines, Vietnam and Malaysia have recently enacted data protection laws, a Bill is before Cabinet in Thailand and development of Bills is reported to be underway in ASEAN members Indonesia, Vietnam (for a stronger law), Laos and Brunei. ASEAN countries had a decade ago made a commitment to ‘adopt electronic commerce regulatory and legislative frameworks’, including to ‘take measures to promote personal data protection and consumer privacy’.[53]

At the 21st ASEAN Summit on 18 November 2012, the ASEAN heads of state adopted the ASEAN Human Rights Declaration,[54] Article 21 of which states

Every person has the right to be free from arbitrary interference with his or her privacy, family, home or correspondence including personal data, or to attacks upon that person’s honour and reputation. Every person has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks.

Although based on the terminology of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the specific references to ‘personal data’ and the right to legal protection increase the internal incentives to all ASEAN members, from both within ASEAN and within each country, to enact data privacy laws. However, the Declaration has come under savage criticism and outright rejection[55] from a coalition of fifty-five global and regional human rights organisations.[56] Among the criticisms are that ‘[i]n many of its articles, the enjoyment of rights is made subject to national laws, instead of requiring that the laws be consistent with the rights’; it ‘fails to include several key basic rights and fundamental freedoms, including the right to freedom of association and the right to be free from enforced disappearance’; and that the rights it states are of a lower standard than those in equivalent declarations in Europe, Africa or the Americas. Consequently, the civil society organisations state that they will not invoke it in their work ‘except to condemn it as an anti-human rights instrument’. The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights considered that the Declaration ‘retains language that is not consistent with international standards’.[57] It is clear that both the Declaration, and the body which helped develop it, the ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights (AICHR)[58] established in 2009, have not yet established credibility.

Macao SAR, Nepal and India are the only Asian countries which are not APEC members but do have a data privacy law. The SAARC, of which both India and Nepal are members, does not have any policies concerning data protection laws or e-commerce harmonisation, and is not a significant influence in this area.

In Africa, the strongest developments have been from the ECOWAS, a grouping of fifteen states[59] where French, Portuguese and English are variously spoken. Under the Revised Treaty of the ECOWAS they agreed in 2008 to adopt data privacy laws. A Supplementary Act on Personal Data Protection within ECOWAS to the ECOWAS Treaty, adopted by the ECOWAS member states, establishes the content required of a data privacy law in each ECOWAS member state, including the composition of a data protection authority. All requirements are influenced very strongly by the EU data protection Directive. Five ECOWAS states have so enacted laws (Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, Senegal and Ghana), and Bills are under elaboration or consideration in, Nigeria, Niger, Ivory Coast and Mali, leaving only six yet to take any action. In some other ECOWAS member states the Supplementary Act, as an additional protocol to a treaty, may be legally binding in creating substantive rights in countries where treaties have direct effect and do not require local enactment. This appears to be the case in Niger, where law is being developed to establish a DPA, to complement the ECOWAS treaty on data protection, which was published in the official journal in 2013.

Less advanced as yet, the East African Community (EAC), a regional group of five East African countries (Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda and Burundi),[60] where English and French are variously spoken, has taken initiatives that encourage the member states to adopt data privacy legislation. Such initiatives include the current discussion of a Draft Bill of Rights for the East African Community[61] which, unlike the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, incorporates the right to privacy. It also includes a right of legal enforcement culminating in a right of appeal to the East African Court of Justice. Also, although not binding, the EAC has adopted the EAC Framework for Cyberlaws Phases I and II in 2008 and 2011 respectively, addressing multiple cyber law issues including data protection. Kenya and Tanzania are currently considering draft bills on data protection.

The Southern African Development Community (SADC) encompasses 15 countries[62] in southern and central Africa, and Indian Ocean states, four of which have data protection laws (Angola, Mauritius, Seychelles and Zimbabwe), and at least three of which have current Bills (South Africa, Tanzania and Madagascar). The South African Bill, which has already passed the lower house, can be expected to have a significant effect on prompting laws in at least the other SADC countries because of South Africa’s role as the regional economic power.

There has already been work done on SADC-wide data protection laws and policies,[63] as part of an EU and International Telecommunication Union (ITU) sponsored harmonisation project relevant to all regions in sub-Saharan Africa (ie SADC, EAC and ECOWAS) which has also produced a ‘Model-law on data protection’ in 2012.[64] The African Union has also prepared in 2011 a draft Cyber Convention,[65] which includes a division on data protection replicating most of the principles of the ECOWAS Supplementary Act.[66] If it proceeds it would be of great significance, because the African Union has 54 member states.

In the Americas, the Organization of American States (OAS), with 35 member states (including from North and South America, and the Caribbean), has started work on data protection in recent years. ‘The Inter-American Juridical Committee adopted several resolutions on this matter, all in an effort to address the regulation of data protection through potential international instruments as well as at the level of the legislation of some OAS member states, and of the processing of personal data by the private sector,’ and the General Assembly of the OAS instructed it[67] to prepare a document of principles of privacy and data protection in the Americas.[68] A set of ‘Preliminary Principles’ were published by the Committee in 2011,[69] which, although brief, included cross-border transfer restrictions based on ‘the same level of protection’ in the recipient jurisdiction, the recognition of habeas data principles, and the existence of an independent supervisory authority. The OAS General Assembly has also resolved to urge member states (and its Secretariat) to participate in and support the work of the Latin American Network of Personal Data Protection (RIPD), to attend the meetings of the International Conference of data protection authorities, and to continue its work on data protection by developing a model law.[70] These resolutions are included within the more contentious context of development of laws for access to public sector information.[71]

In the Caribbean, the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) of 15 states and five associate members[72] is developing an Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) with the European Union as part of the 2008 Caribbean Forum of African, Caribbean and Pacific States (CARIFORUM[73])–EU EPA. Data protection is covered by the EPA and was one of the topics under discussion at EPA meetings in 2012.[74] Data protection is also part of the ITU’s Caribbean Harmonization of ICT Policies (HIPCAR) capacity-building project.[75] Five countries with data protection Bills are CARICOM members or associates, and four already have data protection laws.

In Latin America, the MERCOSUR common market, formed in 1991 involves 10 countries. It currently consists of Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay and Venezuela (since 2012). Bolivia is in the process of becoming a full member, and Chile, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru are associated states. A working group (SGT) was established in 2002 to discuss integration of e-commerce and data protection but seems to have had few results. Data protection is sometimes mentioned as a topic in ongoing negotiations for a EU-MERCOSUR Free Trade Agreement. In short, MERCOSUR has not yet proved to be significant in relation to data protection.

Most data privacy laws include provision for a DPA, a separate institution which has some type of responsibility for the data privacy legislation, involving some enforcement powers, and which are separate from the normal prosecutorial and judicial systems of the country.

Of the 99 countries with data privacy laws, 85 have DPAs. Fourteen countries do not have a DPA, in 10 cases because their laws do not provide for any separate DPA,[76] and in four cases because no DPA has been appointed although provided for in law.[77] The position of the USA is complex, because its Federal Trade Commission acts in many respects as a DPA (including as a member of international associations of DPAs) even though the USA does not meet the criteria for a data privacy law in the private sector.[78] The Table includes the name of the DPA if there is one, or ‘none’ if the law concerned does not provide for one.

DPAs vary greatly in name (common names are ‘Data Protection Authority’, ‘Privacy Commissioner’, and ‘Personal Data Protection Office’, or combinations thereof), functions and degree of independence from other government authorities. Whether a particular DPA can be classed as ‘independent’ is complex question.[79]

Various global and regional associations of DPAs or other data privacy enforcement bodies are of increasing significance. This analysis, and the Table, might not yet reflect fully the diversity of these associations, but does include most of them. Nor does it yet include the website addresses of the various DPAs, but there are other sources for those.[80] There are associations of DPAs globally (two of them), and from the EU, central and eastern Europe, Latin America, the Asia-Pacific, and the francophone countries, but none from Africa or the Caribbean as yet. The membership of most of them is incomplete from their potential pool of members, with considerable overlaps but surprising omissions, as the Table shows.

5.2 Associations of DPAs - Global

The International Conference of Data Protection and Privacy Commissioners (ICDPPC) is the grouping of data protection authorities of broadest scope and greatest longevity, having held an annual conference for 35 years. As Raab points out ‘conference’ is used not only to describe their annual meeting, but as a collective noun.[81] It has accreditation standards which govern which authorities can attend its closed meetings and vote on resolutions, originally quite strict but simplified and possibly weakened in 2010.[82] The ICDPPC members adopt joint policy resolutions, and their annual conference is open to all attendees (except for closed sessions) and has become the leading global data protection conference.

Of the 85 countries which have data protection authorities appointed under their data privacy laws, only 59 national DPAs are accredited to ICDPC (as shown in the Table). The ICDPPC therefore only has 70 per cent of national data protection authorities as its members. After 35 years, this is far from global coverage. It is particularly weak in its lack of members from the Caribbean, but otherwise the gaps in membership are from all regions. However, the ICDPPC’s membership also includes 33 sub-national (state, provincial etc) data protection authorities from Australia, Canada, Germany, Mexico, Spain and Switzerland, a high percentage of such authorities as exist. There are other sub-national DPAs, such as those in Mexico and Argentina. Some are also members of the Global Privacy Enforcement Network (GPEN), Asia Pacific Privacy Authorities (APPA) and other associations of DPAs. The ICDPPC therefore has a total membership of 92, plus the European Data Protection Supervisor.

GPEN originated in a 2007 OECD Recommendation on Cross-border Cooperation in the Enforcement of Laws Protecting Privacy[83] calling for the establishment of an informal network of privacy enforcement authorities. GPEN membership is ‘open to any public privacy enforcement authority that: (1) is responsible for enforcing laws or regulations the enforcement of which has the effect of protecting personal data; and (2) has powers to conduct investigations or pursue enforcement proceedings’.[84] GPEN has members from 26 jurisdictions, all of which have data privacy laws of one form or other, and most but not all of which are OECD members. There are four others members not included in the country Table, the European Data Protection Supervisor (a supra-national body), two Australian state DPAs (from Victoria and Queensland), and a German state DPA (Berlin).

Competition may develop between these two global networks of DPAs, and they could develop diverging memberships, but the operation of GPEN is as yet too recent for these matters to be clear.

5.3 Associations of DPAs – Regional and sub-global

At the sub-global level, the European Union’s Article 29 Working Party is the most influential organisation of DPAs, both because it has a formal role under the European data protection Directive and because of the quality and diversity of its Opinions on data privacy issues. Its membership is co-extensive with that of the EU, but is separately reflected in the Table. It may increasingly have a rival for influence in the Council of Europe data protection Convention 108, Consultative Committee (to be re-named ‘Convention Committee’), as an outcome of the Convention’s ‘modernisation’ process.[85] However, this is technically not a committee of data protection authorities, it is one of the representatives of state parties to the Convention, although nearly half of the state representatives are DPAs.

A larger and also influential body is the (Conference of) European Data Protection Authorities (EDPA) which holds a ‘Spring Conference’ almost every year. Resolutions are usually passed,[86] and on Raab’s analysis are significant to the development of data protection policies in Europe.[87] According to one of its member DPAs,

[o]ne of the most important tasks of the European Data Protection Authorities consists in advising the authorities involved in legislative matters on data protection issues, by pointing out the risks that legislative initiatives might entail and by proposing alternatives which would be more respectful of individual’s rights with regard to the processing of their personal data.[88]

EDPA has quite strict accreditation rules, requiring its members to operate under a law of a state implementing either Council of Europe Convention 108 or the EU data protection Directive, and having independence and appropriate functions and powers.[89] In 2013, for example, Kosovo’s DPA was refused membership because Kosovo was not a member state of either the European Union or the Council of Europe, so it was made a permanent observer instead.[90] Andorra’s DPA is also a permanent observer. Although in theory all member states of the Council of Europe which do have DPAs should be eligible to be accredited to the EDPA, four are not yet accredited.[91] Two Council of Europe member states have not been accredited because they do not have DPAs (Armenia and Azerbaijan). Turkey is excluded because it does not yet have a data protection law. San Marino has a law but has not signed Convention 108, nor joined any association of DPAs. Twelve sub-national DPAs in Europe from Germany, Spain and Switzerland are also accredited to EDPA, as are four supra-national authorities at EU level. EDPA therefore has a high level of coverage of European DPAs.

The next largest DPA network in Europe is the Central and Eastern Europe Data Protection Authorities (CEEDPA) which has 18 members, most recently including Russia but not yet Georgia. The Baltic states and Slovenia are not members. Membership overlaps with the Article 29 Working Party, but many CEEDPA members are from countries which are not yet EU member states. It held its 15th annual meeting in 2012. It is active in mutual support activities and developing policy positions such as approval of reforms of European data protection instruments.[92] CEEDPA states have a common concern as ex-communist states dealing with historical surveillance files of personal data, and in some cases with uncertain democratic institutions. The Western European states have less need for a separate association of DPAs, because only a few of them are not EU member states.

There is also an association of Nordic Data Protection Authorities (NDPA) (Sweden, Norway, Denmark and Finland) which meets every two years. It sometimes acts in concert, as it did in 2011, in sending 45 questions to Facebook concerning its practices.[93]

The operation of other sub-global networks of data protection authorities is less well known, but has been well-documented by Raab.[94] It is not accurate to call them ‘regional’ networks, because some are based on language, some on geography, and some a mix between the two.

The British, Irish and Islands Data Protection Authorities (BIIDPA), an Anglophone grouping within Europe, usually meets annually. As Raab describes it, ‘[l]ess formal connections exist in another, and apparently looser, network that links the DPAs for the United Kingdom, the Republic of Ireland, the Isle of Man (IOM), Jersey and Guernsey, with further connections to Malta, Cyprus and Gibraltar’. He considers that ‘these meetings help the Crown Dependency authorities, who do not sit on WP29, to keep abreast of current issues discussed there’. [95]

The Association of Francophone Data Protection Authorities (AFAPDP) is an active organisation which is influential in francophone countries which have not yet adopted data protection laws. It classifies 41 of the 77 members and observers of the International Organisation of the Francophonie (OIF) as having a data protection law. Of those 41, only 18 are members of AFAPDP, including two Canadian provinces.[96] Only those member countries with DPAs are allowed to vote on issues or for election of positions. Some states intending to develop data protection laws are also members of the association but with no voting rights. In 2009, AFAPDP recommended an initiative for a binding global data protection instrument. AFAPDP aims to develop other policy positions and further agreements.[97] The summit of the Heads of States and governments of the francophone countries has encouraged adoption of comprehensive data protection laws and DPAs in 2004 and 2006.

The membership of La Red Iberoamericana de Protección de Datos, also called the Red Iberoamericana or Latin American Network (RIPD or RedIPD),[98] consists of all the Latin American countries, plus Spain and Portugal. It does not include the other Spanish or Portuguese-speaking countries outside Latin America. It includes in its membership all countries within its community that wish to be a member, irrespective of whether they have yet adopted data privacy laws or have DPAs, so it does not have accreditation requirements equivalent to the IDPPCC or APPA. Its annual conferences pass resolutions concerning data protection, encouraging and assisting other Latin American countries that do not yet have data protection agreements to enact them, and to include independent DPAs.[99]

APPA, a ‘forum’ of national and sub-national DPAs originally only allowed as members those authorities that have been accredited to the International Data Protection Commissioners’ Conference,[100] so the Macao DPA was only an observer at its meetings due to its incomplete legislative basis. APPA has now relaxed its standards somewhat.[101] It now has 16 members from Australia (federal and four states/territories), Canada (federal and British Columbia), Hong Kong SAR, South Korea (two authorities), Macau SAR, Mexico, Colombia, Peru, New Zealand and the USA. Neither Japan nor Taiwan are members due to (at least) lack of a DPA. Singapore will probably join soon, but it is questionable whether Malaysia will have a DPA to qualify, and the Philippines DPA has not been appointed yet. It meets twice per year and has had a primary function of sharing experiences, but has also developed valuable standards on reporting and citing privacy decisions. APPA is expanding its membership (particularly in Latin America) and functions and will probably be more significant in future. It has a considerable and increasing personnel overlap with the APEC data privacy Sub-group, though that is technically a grouping of countries (‘economies’ in APEC-speak) whereas APPA is a grouping of DPAs.

There is also a ‘framework for regional cooperation’ called the APEC Cross-border Privacy Enforcement Arrangement (CPEA) in which ‘[a]ny Privacy Enforcement Authority (PE Authority) in an APEC economy may participate in cross-border co-operation, enforcement and information sharing.’[102] It has as members data protection authorities from only six of the 17 APEC economies which have data privacy laws (Australia, NZ, USA, Canada, Hong Kong and Mexico), plus government departments from Korea (but not their independent DPAs) and Japan. The separate membership of 15 Japanese government agencies indicates the lack of much central coordination in their law. APEC CPEA therefore has membership from relatively few APEC countries.

Although three Caribbean countries now have data protection authorities, they do not have any regional organisation as yet, and nor are they members of ICDPPC or GPEN. There is also no pan-African association of DPAs, despite there now being eight DPAs in African countries, although only some operating in practice. Active regional associations of DPAs seem to be an indicator of maturity of data protection regulation in a region, partly because of the mutual support they provide for each other.

This article and the following Tables don’t constitute ‘big data’, but at least they are more data about global trends in enactment of data privacy laws, and the interlocking memberships of associations of DPAs, than was previously available. Now that we have this more accurate picture, further research becomes possible. It has already made possible an assessment of the influence of European privacy standards on legislative developments outside Europe.[103] Further research is required on such questions as the implications of the increasingly interlocking data export restrictions in this legislation;[104] on the effectiveness of the enforcement regimes in various countries; on the extent of judicial interpretation of these laws, and on other comparative aspects of data privacy laws. All of this requires an accurate account of the incidence, growth and distribution of the world’s data privacy laws.

Some conclusions seem apparent from the data. The expansion of data privacy laws embodying at least a minimum set of OECD/CoE data protection principles continues to accelerate after 40 years. By the 50th anniversary in 2023 of the first such Act in Sweden we can expect that there will be global ‘saturation’ of data privacy laws, in the sense that about 70 per cent of all independent jurisdictions will have such laws, including almost all of the economically significant countries on the globe (with the USA probably the only significant exception). The majority of countries globally will have such laws within another year or two, and there will be more non-European countries than European countries with data privacy laws from that point onward. A large portion of these countries will have laws influenced strongly by ‘European standards’ similar to those of the current EU privacy Directive, including its data export restrictions. The ‘globalisation’ of Council of Europe Convention 108 is increasing its reach and influence, and is likely to compete with APEC’s as-yet-inchoate CBPR process for influence outside Europe. These widely dispersed laws and expanding international agreements build up a considerable global ‘legal inertia’ which it will be difficult to reverse or (eventually) to ignore. Associations of data protection authorities are also likely to increase in importance as venues for contesting influence. These are geo-political facts of considerable significance. There may come a time when the development of technologies and business practices inimical to data privacy will be confronted by these embedded and expanding legal developments more directly than is currently the case.

6.1 Is there now a trajectory?

In 2006, Bennett and Raab, in what is still the most systematic global review of data privacy regulation, presented their ‘main research question’ as whether there was a ‘race to the bottom’, a ‘race to the top’, or something else, in the global development of data privacy protection.[105] They correctly caution that the existence and formal strength of a data privacy law is only one factor by which we should measure data privacy protection in a country, and two other key dimensions are the effectiveness of enforcement and the extent of surveillance. Therefore, globally, there is more than one race to the top or bottom. They noted that, in relation to legislation, the main conditions proposed by globalisation theories of regulation for a ‘race to the bottom’ (data mobility and wide national divergences in laws) were present in the case of data protection legislation.[106] Nevertheless, they found that ‘there is clearly no race to the bottom’, but nor did they find clear evidence of a ‘race to the top’, or global ratcheting up of privacy standards. In particular, they considered that the ‘general suspicion that the APEC Privacy Principles are intended as an alternative, and a weaker, global standard than the EU’ (which suspicion was shared by the author) means that they ‘may serve to slow and even reverse’ the otherwise ‘halting and meandering walk’ to higher standards which the EU Directive had inspired.[107] They concluded that the most plausible future scenario (which I have described as ‘the Bennett-Raab thesis’[108]) was ‘an incoherent and fragmented patchwork’, ‘a more chaotic future of periodic and unpredictable victories for the privacy value’.[109] So they found some ‘upward’ global trajectory influenced significantly by the EU Directive, but sufficiently weak in the mid-2000s that the countervailing weakness of the APEC approach was enough to make the future quite unpredictable.

The position in 2013 is very different. Their thesis may have been in part based on an under-estimate of the number of data privacy laws outside Europe before 2006 (18, not 12), but even if this is not so, events have overtaken it. Now there are almost as many laws outside Europe (44) as there are within Europe (52), and the rate of increase outside Europe is still accelerating. At some point the growth curve of the number of laws may flatten, but there is no sign of that as yet. Bennett and Raab saw APEC as slowing the growth of EU-like privacy laws, but that has been shown not to be occurring, with laws outside Europe showing a very high correlation with ‘European principles’, and little sign of this diminishing in new laws.[110] They did not sufficiently recognise this aspect of consistency in global data privacy laws, which removes some of the ‘incoherence’ they claimed exists, though this consistency was not as apparent back in 2006.

Furthermore, the number of European-like data privacy laws outside and inside Europe (only half within the EU) is not only evidence of the momentum of these developments, but also that the sheer inertia provided by a hundred or more countries with data privacy laws is a global fact of life which it will be difficult for anyone to reverse, including the USA. It is possible that APEC’s Cross-Border Privacy Rules (CBPR), although still not operative, might become an influence, but both a revised EU Directive (as a Regulation) and a revitalised Council of Europe Convention (through ‘globalisation’ which has started, and ‘modernisation’ which is well underway) are likely to prove to be attractive forces that APEC CBPR will find difficult to match. Seven years after Bennett and Raab wrote, there is now much clearer evidence of ‘upward’ global trajectory than they found, provided we keep clear that we are only talking about the existence and formal strength of data privacy laws, not the other factors.

6.2 American exceptionalism and increasing isolation