|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Law, Technology and Humans |

‘If You Prick Us Do We Not Bleed?’: Marvel Comics’ Vision: Director’s Cut Re-Evaluating What It Means to Be Human

Leah Henderson

Griffith University, Australia

Abstract

Keywords: Marvel Comics; Marvel Cinematic Universe; Graphic Justice; Law and Comics; Revenge and Accountability in Comics; Marvel and Frankenstein; Marvel and Shakespeare.

1. Introduction

Vision: Director’s Cut (2017) is a short comic series by Tom King and Gabriel Hernandez Walta, distributed in six volumes. It follows Vision, a lonely robot Avenger superhero who builds his own robotic family out of his desire for love and happiness,[1] and their struggle to lead a ‘normal’ suburban life. They are subject to social ostracism and abuse by a neighbourhood that refuses to accept them as part of the human community. Although these characters are technically artificial, they can still think and feel like humans and be vulnerable to hurt and pain by the same means as all sentient creatures. The story reveals these human feelings by focusing on the family’s attempts at happiness in the face of constant adversity. Therefore, Director’s Cut seems to argue that any human-like artificial intelligence (AI) created ought to become subject to inalienable human rights, including the right to human dignity and equality. Yet, Director’s Cut is not literally about conscious AI but rather the subject of conscious AI is used as a metaphorical vessel to respond to long-standing literary discussions about humanness versus monstrousness, what it means to be a human, and who gets to dictate the definition.

The comic superhero genre provides a way for thinking through the dominant concepts of law, justice and humanity, as well as imagines alternative ideas.[2] Vision: Director’s Cut engages the question of how an artificial superhero—Vision—might live a ‘normal’ life with a ‘family.’ In doing so, it presents a narrative about the need to extend social acceptance, human rights and legality to the technological non-human. It simultaneously explores what it means to be human and presents a post-human challenge to human exceptionalism. This challenge investigates justice within the law by exploring differences between pre-eminence and fairness, and vigilante justice enacted by wronged individuals. Examining the way in which the comic draws upon classic texts—most notably Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; Or, the Modern Prometheus (1818) and William Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice—this article works through and unpacks the comic’s concerns with the exclusion of minorities from social life, the monstrous capabilities of ‘civilised’ humanity, and the inconsistencies of universal law and human rights.

Section 2 outlines both the plot of Director’s Cut and the context in which the narrative plays out—in terms of Vision’s role within both the Marvel Comics and the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Section 3 examines the way in which the text explicitly engages with questions about the applicability of law and justice to the conscious AI being. This includes not only the discussions of ‘pre-eminent justice’ in which Vision engages with his family, but also questions of both whether murdering a synthezoid is a crime and whether a synthezoid can be held responsible for murder. These legal questions are then related to the broader authorial intentions of Director’s Cut, which can be explored through a comparative analysis to canonical texts, Shelley’s Frankenstein and Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice. Section 4 explores the way in which Director’s Cut is a contemporary, science-fiction rendition of Frankenstein, focusing on the loneliness of an artificial creation that seeks companionship, love and belonging. The loneliness of both Vision and the creature in Shelley’s novel is caused by their rejection from a mainstream society that distrusts and fears them for their physical appearance and artificial construction. Both texts portray a two-tiered argument. The first part argues that while it may be morally and ethically questionable to artificially create beings, once these beings are created and sentient they ought to be treated with human dignity. The second part argues that true monstrousness is not the creation of an artificial life but the cruel reactions against these creations by an unaccepting community. True monstrosity lies within the abusive treatment they experience, and it is through the outsiders’ emotional and physical pain that these texts reveal their legitimacy as humans.

Section 5 takes up the theme of social exclusion by focusing on textual references in Director’s Cut to Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice, which explores how the escalation of harm and violence against an outsider causes them to seek vengeance. Like Frankenstein, Shakespeare’s play also portrays an individual experiencing the social rejection of his peers, who perceive him in a dehumanised state to justify their own biases. Yet, the outsider insists upon his own humanness, particularly in Shylock’s most famous speech in which he states, ‘if you prick us do we not bleed? ... And if you wrong us, shall we not revenge?’[3] Director’s Cut aligns itself with centuries-old notions of what it means to be human through the experiences of trauma and vulnerability that consequentially lead to the committing of monstrous acts distinct only to the human species. Shylock, Frankenstein’s creature, and Virginia and Vision all seek revenge for trauma suffered. These are significant character transformations that argue their true humanness because vengeance is a distinctly human trait inimitable by other life forms.

2. Contextualising the Scene: What Is the ‘Vision’ of Vision: Director’s Cut?

In the Marvel multiverse metanarrative, Vision was created by the robotic villain Ultron in his pursuit to destroy the Avengers.[4] Yet, Vision defies Ultron and helps the Avengers defeat him.[5] The brain patterns of the superhero Wonder Man were artificially recorded after he died, and they were later transmitted into Vision and reappropriated to help him formulate an organic mind. Mainstream audiences would be familiar with Vision’s origin storyline from the Marvel film Avengers: Age of Ultron (2015). Vision is also a key player in the later film Avengers: Infinity War (2018), as the superheroes try to stop Thanos from gaining all six Infinity Stones. Thanos and his followers repeatedly attack Vision in this film, trying to kill him for the Mind Stone that is embedded in his forehead and keeps him alive. The last battle scene shows Thanos ripping it from Vision’s skull, killing him, and then carelessly tossing his body aside. This deviates from the comic, The Infinity Gauntlet (1991), on which the film is based because the Mind Stone is not kept in Vision’s forehead. Nevertheless, Infinity War is significant in reiterating the same notion in Director’s Cut that Vision is repeatedly treated as different from, and less than, humans.

Individuals struggling against prejudice for being unique is not a new idea for Marvel Comics. Since the first issue of X-Men in September 1963, mutant stories have been about the struggle of people who are naturally different from the mainstream and face social ostracism, medical torture, murder, and, in some stories, genocide. The X-Men superheroes protect the world time and again while simultaneously trying to defend themselves from the very people they protect. King and Walta’s Director’s Cut fits within this Marvel Comics tradition examining the struggles of a rejected minority. The narrative focus is on the ‘family’ that Vision has created—also deploying the brain patterns of Wonder Man initially used to create him—consisting of his ‘wife,’ Virginia, and two ‘children,’ Viv and Vin.

The story begins with the family settling into a middle-class suburban life in Arlington, Virginia. Vision leaves every morning to work at the White House, protecting the president. His kids, Viv and Vin, attend high school, with Virginia acting the part of housewife. They resemble the ideal suburban nuclear family. Vision sets his family task of acting and behaving just like humans. Aesthetically they can do this by dressing in the right clothes and living in an idyllic, double-storey home. They even sit down at the dinner table each night as a family despite not requiring food to sustain themselves. Yet, the story shows that being human is never simple. Cultural belonging is not just an aesthetic experience, but also requires inclusion into a community. The rejection the family feels is physically manifested in vandalism of their house and rude comments, such as the teenage boys who spray paint ‘go home socket lovers’ on their garage door,[6] and the teenage girl who asks Vin if he is ‘normal,’[7] or even the school principal that calls the children ‘guns’[8] and ‘metal.’[9] Even those neighbours that are not abusive become exploitative when they turn the family into a circus spectacle by taking ‘pictures with’ and ‘of the Visions to post on their various’ social media (see Figure 1).[10] The small panels on page 11 of Volume 1 reveal the dismayed Visions standing in their front yard, clearly not enjoying being harassed with a camera. This treatment is just the beginning and foreshadows the escalation to come.

Figure 1. Vision is routinely subject to neighbourhood exploitation.

Image credit: Tom King, Gabriel Hernandez Walta and Jordie Bellaire. Vision: Director’s Cut. Volume 1. New York: © Marvel Comics, June 2017.

The Vision family’s community feels bitterness and distrust towards this new type of life form thrust upon the locals. The first volume opens with the scene of neighbours George and Nora arguing on the Visions’ front porch. George is annoyed because Nora insisted that they give the Visions a warm welcome to the neighbourhood and he is her unwilling accomplice: ‘It’s just unnatural,’ says George, ‘they’re toasters. Fancy, red toasters. They’re not you and me.’[11] Such an opening scene not only foreshadows the struggles that the Vision family will face, but also presents the underlying premise that the comic itself is challenging: human exceptionalism. The premise of human exceptionalism is the belief that humans are superior to all other living natural beings, justifying or legitimising the status quo—humans as the dominant species on Earth. As Srinivasan and Kasturirangan argue, ‘the zoӧpolitical logics of human exceptionalism play a key role in the pursuit of’ human well-being ‘by rendering nonhuman life killable.’[12] This belief of human exceptionalism is tested by the presence of the Vision family and reveals the ugly side of this exceptionalism ideal when their lives are put in danger. Director’s Cut elaborates in great nuance this central notion of killability through the story arcs of death and vengeance, such as when the Grim Reaper attacks the family home and severely wounds Viv, and when Victor Mancha kills Vin. However, the tragic tone of these narratives presents an implicit argument about the value of all sentient creatures and that their unprovoked killing is unjust for all, not just for humans.

The equation of ‘sentience’ to ‘humanness,’ thus, contributes to the questioning of human exceptionalism that has occurred in recent years. For example, Anna Grear notes that ‘increased understanding of the multiple forms of intelligence and vulnerability distributed across animal, bird and fish populations, and among trees and other living ecosystems, has generated impetus towards the award of rights to range of non-human beneficiaries.’[13] Grear illustrates the way human rights are being rethought to encompass non-humans—including, for example, the calling for and granting of rights to nature and animals. In Vision: Director’s Cut this new awareness of the sentience, intelligence and vulnerability of other life forms occurs in the context of synthetic life, arguing that they are deserving of certain rights alongside humans. The comic portrays this when the family is attacked at their home. One night while Vision is away an intruder breaks in with the intent to kill and Viv ends up severely wounded. Virginia kills the intruder and hides the body, and the family try to continue on with their lives. However, tragedy strikes again when a close friend, Victor Mancha, betrays the family and kills Vin. This transforms Virginia and Vision from people trying to constantly do the right thing and be good people, into heartbroken parents intent on revenge. Their character transformation means that they now embody humanness and what it means to feel and act human, rather than just aesthetically imitating an unconvincing portrayal. It is these emotional experiences that are the driving force of the comic.

The vengeful killing of Victor Mancha raises questions not only of humanness, but also around what actions constitute monstrousness—two points Marvel Comics have repeatedly engaged. Through the symbolic portrayal of the superhero character, the comics explore how acting monstrous is generally part of what it means to be human. One such example is in The Infinity Gauntlet (1991) when Hulk and Wolverine have a personal conversation:

Hulk: And I’ve come to the conclusion I like you, Shorty.

Wolverine: Why’s that?

Hulk: Because in our own ways, we’re both monsters, pal.[14]

These two characters are superheroes in the sense that they are capable of extraordinary heroic acts, but the same powers that enable them to do these great things are also the sources of their monstrousness, which is something with which they have to continually grapple. Stan Lee himself has confirmed that when formulating the Hulk character, he drew inspiration from Shelley’s Frankenstein and Robert Louis Stevenson’s novel The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886).[15] Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Marvel Comics even published Frankenstein adaptations in short series that, according to Shane Denson, ‘the oft-told tale is expanded and continued beyond the frame of both Shelley’s novel and the Universal films of the 1930s.’[16] Frankenstein is a tale that Marvel Comics is repeatedly reappropriating, of which Vision: Director’s Cut is one of these appropriations. However, before engaging in an examination of the way in which Director’s Cut is a modern Frankenstein tale, we will explore its representations of law, crime and punishment.

3. Crime and Punishment: Preeminent Justice, Legal Responsibility and Being ‘Like Everyone Else’

The law is overwhelmingly present in Director’s Cut. As a story about injustices against non-humans, this overwhelming presence makes these injustices institutional and cultural. This point is also implied through the presence of the Avengers and their role as deliverers of justice. Yet, Avengers narratives repeatedly separate the difference between justice and the law. As Jason Bainbridge argues:

the superhero and the supervillain operate outside the law. The former replaces the law with a form of substantive justice while the latter seeks to invert or overturn the law in favour of a new grundnorm (or anti grundnorm) that best serves their vision for how society should operate.[17]

Similarly, Timothy Peters argues that ‘cultural legal and criminological studies of comic books have identified the way in which superheroes operate as figures of justice, working either with or beyond the law.’[18] Within Marvel superhero stories the law is constantly treated as a fluid, tangible concept rather than something concrete. In this way, Marvel superheroes work for justice whether it is ‘with or beyond the law.’ However, if superheroes operate beyond the law, then the question of morality must arise. Thomas Giddens elaborates on the differences between morality and legality, and the reflective distinctions between positive law and natural law. He explains, ‘positive law argues that morality does not necessarily have any place in the assessment of whether something is law,’ whereas ‘natural law ... holds that law is (or should be) a moral system.’[19]

Yet, as this section will discuss, when the Vision family needs justice and seeks vengeance, the Avengers superheroes do not offer to help them. The family also live among government workers and are in close proximity to the hub of federal law, Washington D.C., as Vision is assigned by the Avengers to protect the president. This assignment creates greater insult when Vision is used to protect the president, but no one offers to protect him or his family. Giddens argues that recognisable ‘five-dimensional objects’ that aesthetically represent the law—‘such as monuments, ideas’ and ‘legal structures’—are subject to interpretation when ‘the role of human creativity in the constitution of seemingly stable objects, renders these things interpretive, indeterminate, and contested.’[20] Thus, the legal aesthetics of this comic—the setting in Arlington, Virginia; the government workers for neighbours; the presence of superheroes and villains; and Vision’s position in protecting the president at the White House—are deliberately placed objects that question and criticise the behaviour of these legal uniform bodies that are the federal government and the White House, and those organisations working alongside these legal bodies, the Avengers. The family is surrounded by figures that either represent superhero justice or institutional justice, yet still the story ends in tragedy. This is a deliberate thematic trait telling readers that both the superhero form and institutional form of justice have failed this family.

Pre-eminence, the highest form of institutional justice, is challenged in this comic. Virginia and Vision debate the difference between pre-eminence and fairness. Vision himself aligns justice with an idea of ‘pre-eminence’ rather than ‘fairness,’ wherein the former alludes to a hierarchy of justice in which the present justice legal system works, and the latter alludes to the elementary understanding of justice. Vision lectures the difference to his wife: ‘Fairness is a simple mathematically determined balance, the lowest form of justice. Preeminence, however, is the assertion of complex covenants over instinctual norms. The highest form of justice. Understanding and embracing preeminence moves us closer to humanity.’[21]

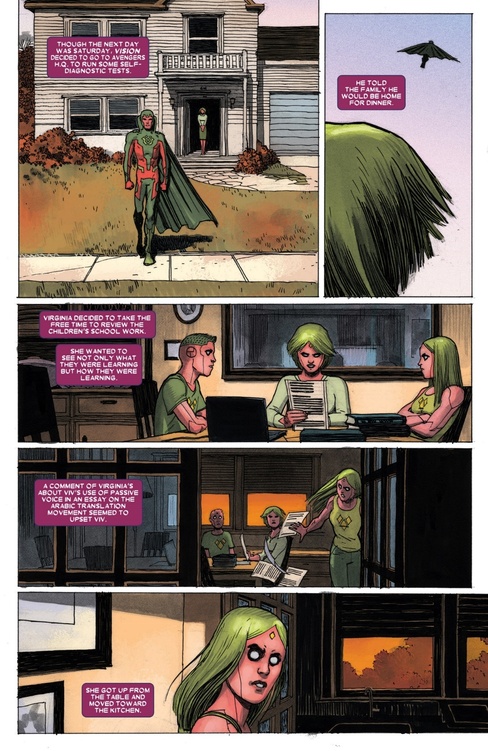

While Vision has won the debate, the comic shows it is the basic lack of fairness that has caused so much tragedy in the family’s lives. One evening while Vision is away, a man breaks into their house and attacks the family. Readers are caught by surprise, as a domestic scene of Virginia reviewing the kids’ homework is horribly interrupted when a large blade is stuck into Viv’s torso (Figure 2). This sudden event has been artfully manipulated to be unexpected and shocking. Page 19 of Volume 1 is cut into small panels that slowly drag out the movements of a docile domestic scene. Then, page 20 opens to a full-length panel of Viv hanging off a curved knife, the glass from the window is shattered in mid-action, and her wires are broken and hanging out of her like spilled intestines (Figure 3).

Figure 1. Domestic scene of Virginia reviewing the kids’ homework is horribly interrupted (page 19).

Image credit: Tom King, Gabriel Hernandez Walta and Jordie Bellaire. Vision: Director’s Cut. Volume 1. New York: © Marvel Comics, June 2017.

Figure 2. Viv hanging off a curved knife (Page 20).

Image credit: Tom King, Gabriel Hernandez Walta and Jordie Bellaire. Vision: Director’s Cut. Volume 1. New York: © Marvel Comics, June 2017.

The perpetrator enters the house, revealing himself to be the Grim Reaper, a villain of the Marvel multiverse and one of the Avengers’ many enemies. The Grim Reaper targets the family because he feels cheated of his deceased brother, Wonder Man, the superhero Vision used to artificially formulate his family, representing to the Grim Reaper a desecration of his brother’s dead body. He lashes and strikes with his blade and yells at them, ‘frauds! Artificial jokes! ... Imposters! ... Everywhere I look, I see you. Everyone is so eager to share their photos of the new perfect family. ... A family made from a stolen copy of my own brother!’[22] The scene is doubly emotionally charged from the Grim Reaper’s rage and the children’s shock and trauma at being physically attacked. The Grim Reaper makes it known this attack is personal; their very existence offends him. This traumatic scene presents an intrusion to the Vision family’s right to life, to feel safe in their own private home, and that the basic laws against murder of a human should also apply to the murder of synthezoids.

Virginia protects her children by beating the Grim Reaper over the head with a metal object, but in her panic she accidentally kills him, despite the repeated protestations by Vin to ‘stop!’[23] Afraid of the ramifications, she tells the children not to ‘tell’ their ‘father,’[24] and proceeds to bury the body. Later, Virginia tells Vision that the Grim Reaper escaped and Vision tries to save Viv’s life. He takes Viv to Tony Stark’s laboratory to repair her injuries. In this scene, Vision explains that ‘when the Grim Reaper attacked her, the damage to Viv’s neuro-spleen was extensive,’ to which Tony flippantly replies, ‘obviously.’[25] By Tony’s expression it is clear that he does not take the situation as seriously as he would if a human were attacked. Additionally, neither he nor the Avengers offer to seek out the Grim Reaper (who they do not know is dead) and bring him to justice. The lack of consideration for Vision’s family is revealed in the absence of a reaction to the attack.

The comic does not make clear whether this intruder would have been held responsible for trying to kill three robots. However, it is clear that Virginia would be held accountable for killing him, as her immediate reaction is to hide the body, because by doing so Virginia is hiding the evidence of her guilt and accountability in the eyes of the law. In addition, the circumstances change after their son Vin is killed by Victor Mancha, a part-human, part-synthezoid who was spying on the family at the request of the Avengers.

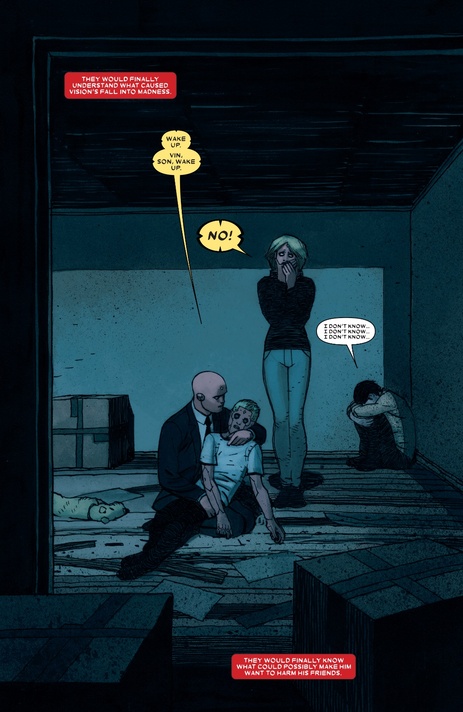

The Avengers assign Victor to investigate the Visions because they are suspicious about the events surrounding Viv’s attack. Victor enters into their lives as their uncle and Vision’s brother, as he was also originally created by Ultron. Yet, his plans are foiled when Vin accidentally walks in on Victor’s phone conversation with the Avengers in which he is caught saying, ‘I have his trust, the whole family’s, I swear it’s not that. Vision just never talks about it. The reaper. ... But we’ll get it from him, I swear.’[26] When Vin tries to run away, Victor begins to electrocute him with lightning bolts zapping from his hands. Page 22 of Volume 5 is a full panel of Vision holding Vin and Virginia and standing over them in shock and terror (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Vision holding Vin and Virginia and standing over them in shock and terror (page 22).

Image credit: Tom King, Gabriel Hernandez Walta and Jordie Bellaire. Vision: Director’s Cut. Volume 5. New York: © Marvel Comics, October 2017.

The caption at the top of the page reads that the Avengers ‘would finally understand what caused Vision’s fall into madness.’[27] This comment foreshadows Vision turning against the Avengers and breaking into Mancha’s cell, and Virginia ripping Mancha’s heart out. This scene reveals that grief and betrayal are the catalysts for Vision’s and Virginia’s character transformations. The love for their family has made them vulnerable to this irreparable hurt. Grear argues the notion of vulnerability is an intrinsic reason to extend human rights to include non-human beings: ‘The ongoing power of human rights as a politics and ethics of singularity arguably now depends upon such a reorientation and on embracing vulnerability as the material affectability of the more-than-human entanglements we call the world.’[28] The repeated tragedy that befalls the Vision family exploits their vulnerability because, although they do not have organic bodies, they can still be hurt, killed and emotionally torn apart by the same means as everyone else.

After Vin’s tragic death, Vision and Virginia have reached their personal limitations of civility and vengefully kill Mancha in his prison cell. This marks the transformation of the Vision couple from victims to angry vigilantes blinded by their pain. When Wanda tries to stop Vision from entering Mancha’s cell, she says, ‘if you do this ... you can’t come back. You’ll be like everyone else,’ to which Vision replies, ‘I want to be like everyone else.’[29] This contradicts Vision’s earlier argument about pre-eminence. He is working on the pretence of fairness, or lack of it—that the fairness of his basic human rights was grossly infringed, unaccounted for by the law, and that fairness means he has a right to revenge. In addition, this character transformation signifies that not only does being human mean to be vulnerable, but also vengeance is a distinctly human trait. It is Vision’s and Virginia’s act of revenge that brings them closer to humanity. Hence, they become like ‘everyone else.’

4. Adaptation of Frankenstein; Humanity vs Monstrosity or Humanity as Monstrosity?

Vision: Director’s Cut is a modern retelling of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; Or, the Modern Prometheus, published in 1818. The novel is about an overly zealous scientist, Dr Frankenstein, who seeks to artificially create life. He succeeds this mission by assembling body parts from corpses and using electricity to awaken him. Yet, this is a tale of caution, for once Frankenstein succeeds he is so horrified at his own creation that he abandons the creature, and this has tremendous consequences. The alternative title The Modern Prometheus refers to the ancient Greek tale of the titan Prometheus, who defies the gods and gives humans on Earth the power of fire, and for this he is punished by Zeus. By referring to this ancient tale in the title, The Modern Prometheus, Shelley suggests that the power of giving life should be left only to the gods, and not transferred to humans. Fire is a great responsibility, as is the creation of life. As Josephine Johnston argues, ‘Mary Shelley explores at least three aspects of responsibility: Victor’s responsibility for the deadly actions committed by his creation and the threat the creature’s existence poses’ to humans, as well as ‘Victor’s responsibility to his creation for the creature’s welfare and well-being.’[30] Likewise, the responsibility of Vision as the creator and the welfare of the Vision family in a hostile environment are key themes in Director’s Cut.

The conscious, sentient robot and Frankenstein are more directly linked than may be initially realised. Michael Szollosy argues that ‘the robot monster’ is ‘a direct descendant of monsters that we have grown accustomed to since the nineteenth century: Frankenstein, Mr. Hyde, vampires, zombies, etc.’[31] Likewise, Gorman Beauchamp has stated that ‘just over a century’ after Mary Shelley released her novel, ‘Karel Capek, in his play R.U.R., rehearsed the Frankenstein myth, but with a significant variation: the bungled attempt to create man gives way to the successful attempt to create robots; biology is superseded by engineering.’[32] The Vision family and Frankenstein’s creature are also comparable because they are both feared and rejected by the societies into which they are artificially born. The basis for this rejection is the artificiality of their birth and that they physically look inhuman and monstrous. In both Director’s Cut and Frankenstein the artificial creations experience rejection derived from their physical appearances that make them look like monstrous outsiders. This is articulated through the reading literature as a point of existential contemplation. When Shelley’s creature reads classic novels he is perplexed because he can understand and empathise with the characters in these books, but he physically looks different to these characters: ‘My person was hideous, and my stature gigantic: what did this mean? Who was I? What was I? Whence did I come? What was my destination? These questions continually recurred, but I was unable to solve them.’[33] The creature sees himself as others see him: ‘hideous’ and ‘gigantic.’ That the Vision family are repeatedly referred to as ‘toasters’[34] is derived from their physical appearance. Their skeletal frames are covered in red metal and their eyes bare no pupils or irises.

Within both texts this societal rejection has also created a deep loneliness within the outsider that is sought to be alleviated. After being rejected from his creator and the rest of society, the creature philosophically contemplates his own existence:

Like Adam, I was created apparently united by no link to any other being in existence; but his state was far different from mine in every other respect. He had come forth from the hands of God a perfect creature, happy and prosperous, guarded by the especial care of his Creator; he was allowed to converse with and acquire knowledge from, beings of a superior nature: but I was wretched, helpless, and alone.[35]

In Volume 6 of the miniseries, Director’s Cut briefly recounts Vision’s artificial birth. When Vision first opens his eyes Ultron was there to greet him. Ultron welcomed Vision into the ‘world of the living,’ but admitted that he would still ‘never know but a half-life.’[36] Not only is this evidence of the comic’s morale that it is inhumane to create artificially conscious beings that can never live a full human life, but also this perspective allows readers to understand Vision’s loneliness and why he was driven to create a synthezoid family alike to himself. This is also further explained in the memory flashbacks of his past relationship with Wanda Maximoff, another Avenger superhero. When their relationship breaks down the reader sees Wanda callously antagonising Vision by repeatedly calling him a ‘toaster’[37]—elaborating that the reason Vision wants a synthezoid family is because he was unable to find a happy relationship with a human. Likewise, Shelley’s creature asks Frankenstein to make him a bride, insisting that on the fulfilment of this task his ‘evil passions will have fled, for I shall meet with sympathy; my life will flow quietly away, and, in my dying moments, I shall not curse my maker.’[38] While Frankenstein agrees to the creature’s request, he ‘could not collect the courage to recommence’ his ‘work,’ despite that he ‘feared the vengeance of the disappointed fiend.’[39] So, the creature seeks not only vengeance on Frankenstein for abandoning him, but also his denial of a companion. Therefore, Vision’s story is an instance in which the creature is granted a companion and a happy family, portraying what might have happened if Frankenstein’s creature were granted his wish.

Even more than Shelley’s novel, Director’s Cut bears similarities to those classics of the Frankenstein archive: James Whale’s Frankenstein (1931) and Bride of Frankenstein (1935). While often noted as misrepresenting Shelley’s articulate and sensitive monster, Whale’s films maintain the focus on the question of what constitutes humanness—the theme that Director’s Cut takes up. The 1931 film Frankenstein remains honest to the novel as a cautionary tale against trying to artificially create life. Yet, there are some vital differences to the characterisations that change the audience’s stance. For example, Paul O’Flinn has observed that Frankenstein’s implant of a clinically abnormal brain into the creature’s skull has twisted Mary Shelley’s argument ‘that the monster’s eventual life of violence and revenge is the direct product of his social circumstances.’[40] O’Flinn further states that ‘the film deletes this reading of the story through its insistence that the monster’s behaviour is not a reaction to its experience but biologically determined.’[41] This also holds Frankenstein less accountable for creating him and then abandoning him—whereas in Director’s Cut Vision is both creator and creature, therefore, referencing both the monster and Frankenstein himself. Unlike Frankenstein, Vision loves his family, he works hard for them, and mentors and protects them. Yet, the question of whether it is ethically and morally legitimate to artificially create life is still a huge consideration within the comic. This is summed up by the narrator’s words in Volume 3 of the comic series: ‘Vision thought he could make a family. A happy, normal family. It was merely a matter of calculation. The right formula, shortcut, algorithm. What a shock then ... to discover that it was all beyond him.’[42] The point is that every action has a consequence. Vision was so eager to create a family he did not consider all the ramifications.

Vision’s questionable actions in creating an artificial family also communicate the cruelty and inhumanity of artificially creating life, but that once that life is created it should be recognised and valued—and entitled to basic human rights. Despite the fact that Whale’s 1931 filmic rendition diverts responsibility from Frankenstein, the film’s ending seeks to elicit sympathy from the audience when a mob of angry townsfolk chase the creature into the tower of a windmill. They set the windmill alight, and the crowd cheers while the creature screams desperately through the tall flames. Anna Siomopoulos classifies the film ‘as both a horror film and a mob violence film because it imagines a social subject whose construction from the body parts of others provokes mob violence.’[43] This is akin to the argument that once a life is created it has a right to live. Likewise, in Director’s Cut, the Grim Reaper attempts to kill the Vision family at his own disgust at their artificial creation. Vigilante violence is used in these texts to discuss the irrational hatred these artificial creatures are forced to face for merely existing, and resembles the type of mob behaviour that has been repeated throughout history against minorities for being different. Such tragedies include the racist murders against Africans Americans by white supremacists, Russian Pogroms, the Rwandan genocide, and the Indonesian mass killings of 1965–1966. These are all examples in which racial, religious and political ‘others’ were obliterated by civilian mobs.

Such hatred manifests itself into the physical act of causing bodily harm. Vigilante violence against an outsider, as it is used in Whale’s film and in Director’s Cut, focuses the injustice as violence upon the body. This links to Shelley’s novel because, as William P. MacNeil contends, ‘rights are allegorised in the figure of Frankenstein’s monster, and thereby critiqued as the “monstrous body of the law”.’[44] It is the body that becomes the focus because the feelings of others manifest into physical acts of intent, much like the full-page scene of Viv with a blade stuck in her torso.[45] This scene also portrays Grear’s argument about the extension of human rights to non-humans by showing the pain inflicted upon the non-human body.[46]

Director’s Cut is not only comparable to Whale’s 1931 film, but also the sequel. Whale redeems the failing of the first film by reconsidering Frankenstein’s character portrayal with his sequel Bride of Frankenstein in 1935. Twelve minutes into this sequel film, Frankenstein and his fiancée Elizabeth are in their home when he finally admits his wrongful actions: ‘Perhaps death is sacred, and I profaned it.’ He says, ‘for what a wonderful vision it was, I dreamed of being the first to give to the world ... the formula for life. Think of the power!’[47] Elizabeth replies that ‘we are not meant to know these things.’[48] Frankenstein revealing his selfish motivations scores the sympathetic tone towards the creature that the audience will carry with them throughout the continuing narration. In addition, the doctor calling his creation a ‘wonderful vision’ can link to the double meaning in Vision’s own name. In Avengers Origins, Vision chooses a name for himself after speaking to the Wasp about his purpose in life. She tells him that ‘you come up with a vision of what you aspire to ... and then you work to make it happen.’[49] Then in Director’s Cut Vision creates Virginia, Vin and Viv in his vision of the perfect, loving family. Therefore, these artificial creations reflect the dreams and desires of Vision as their maker, symbolically signifying humanness because it is a human attribute for parents to create and mould their children in their own vision.

In this tone, the comic deliberately ambiguates whether it is unethical to create artificial life because the reader cannot help but sympathise with the lonely robot who wants love and belonging. In the concluding scenes of Director’s Cut, Vision secretively enters a hidden room in the house and sardonically hums a chilling tune as he wires together a new robot: ‘Row. Row. Row your boat. Gently down the stream. Merrily. Merrily. Merrily. Merrily. Life is but a dream.’[50] This singing has the effect of unnerving the reader, as the events of Vision’s life in this comic have been anything ‘but a dream.’ This ironical singing forces readers to wonder whether creating a new family member is such a good idea, but the cliffhanger means there is no resolute answer to this. In contrast, Bride of Frankenstein makes a direct statement that artificially creating life out of loneliness is still wrong. In this sequel the creature has escaped the burnt windmill and treks through the countryside and wilderness, scaring anyone he encounters with his horrifying appearance. These scenes portray the creature’s loneliness and the reason why he eventually turns to Dr Pretorius, a heartless, megalomaniac scientist that tells the creature he will make him a bride. Rather than feeling rejoice when the creature welcomes his new bride into the world of the living, the woman is horrified at being brought back to life and shrinks away from her proposed suitor, a stranger she does not know. ‘She hate me,’ the creature laments.[51] This despairs the creature into the realisation that their existence is not natural and that he will never find happiness. ‘We belong dead,’ he determines as he kills himself, his new bride, and the villainous Dr Pretorius.[52]

Overall, Vision creating this new robot poetically reinforces that these AI creatures are just as human as everyone else. Ironically, it is this illogicality—even though Vision knows the future ramifications of his actions—that makes him human, because it is a human characteristic to repeat mistakes and allow emotions to overpower a sense of judgement. As Vision says to his wife at the start of the story, ‘the pursuit of a set purpose by logical means is the way of tyranny. ... The pursuit of an unobtainable purpose by absurd means is the way of freedom; this is my vision of the future. Of our future.’[53] This speech is significant in discussing the messy nature of humanity, that humanness is at its core a feeling rather than a physicality. Once again there is a double meaning in the word ‘vision’ that speaks to his intentions in not only to create a loving family, but also his plight to embody humanness in every sense of the word.

5. The Merchant’s Pound of Flesh: Human Justice of Inhuman Vengeance?

As demonstrated, Director’s Cut discusses age-old philosophical questions about what it means to be human, what constitutes humanness, and who gets to dictate this. These questions have arguably been around since the dawn of humankind and have repeatedly arisen throughout the centuries within canonical literature, including William Shakespeare’s play The Merchant of Venice. This text is significant because it portrays the ‘Othered’ figure trying to exist within a prejudiced society, and the way in which that outsider is driven to vengeance.

Linking to earlier discussions in Section 4, The Merchant of Venice also argues that just because someone looks different from the rest of the community that does not make them any less human and equal. The challenge of the Vision family’s appearance to the rest of the community is supported by Vin’s reading of Shakespeare’s play The Merchant of Venice. The play is about said merchant, Antonio, who takes a loan from a moneylender named Shylock. The moneylender is a racial outsider in seventeenth-century Catholic, Venetian society, and he is best known for his speech protesting against the anti-Semitism he experiences as a Jewish man:

Hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions,

senses, affections, passions, fed with the same

food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to

the same diseases, healed by the same means,

warmed and cooled by the same winter and

summer, as a Christian is? If you prick us do we

not bleed? If you tickle us do we not laugh? If

you poison us do we not die? And if you wrong

us shall we not revenge?[54]

In Director’s Cut, Vin becomes engrossed within this speech and repeatedly reads it aloud as he wanders throughout the house. He finds comfort in this identification with Shylock as an expressive outlet for his ostracism in the schoolyard. Yet, this speech is also the point at which Vin suffers an existential crisis when he turns around and asks his father, ‘if you prick me, do I bleed?’[55] A synthezoid robot can figuratively bleed, but they cannot literally produce blood. Yet, he can still be physically and mentally hurt, which the attack by the Grim Reaper proved. So, although they may look different, that does not deny the fact of their sentience and vulnerability. Once again this touches upon Grear’s argument of vulnerability as a legitimacy for human rights.

However, this is Vin’s only comparability to Shylock through his struggle for self-identification—whereas Vision and Virginia adapt like Shylock in becoming vengeful against those who have wronged them. Antonio begrudgingly borrows 3,000 ducats from Shylock, who, in turn, begrudgingly gives him the money. But if Antonio does not pay the debt in time Shylock will take from him a pound of Antonio’s flesh. During this transaction there is a sparring of words instigated by Antonio, who dislikes Shylock for being Jewish. Shylock states his reasons very clearly for seeking revenge in his ‘pound of flesh’ deal: ‘Fair sir, you spit on me on Wednesday last, You spurn’d me such a day; another time, You call’d me dog.’[56] Comparable to this is Shakespeare’s other play, Othello, which is about the Moor of Venice who jealously kills his wife after being misled by the antagonist Iago. The story explores Othello’s continual subjection to racial prejudice and the way in which he is manipulated to commit a crime of passion. Likewise, Shelley’s creature is motivated by jealousy and seeks revenge against Frankenstein. The creature claims that ‘when I discovered that he, the author at once of my existence and of its unspeakable torments, dared to hope for happiness ... then omnipotent envy and bitter indignation filled me with an insatiable thirst for vengeance.’[57] Director’s Cut draws from this idea in both Othello and The Merchant of Venice when Virginia rips Mancha’s heart out of his chest—an action that visually recalls Shylock’s ‘pound of flesh’ as repayment. Virginia’s need for revenge drives her to commit a crime of passion. Jealousy and revenge are murder motives distinct only to humans and reinforces the message that to act monstrous is to act human.

Yet, with revenge comes the vigilante’s personal downfall. When Shelley’s creature explains his reasons for vengeance, he also admits that he killed ‘the innocent,’ ‘the lovely and the helpless,’[58] and, hence, the creature has become a bad, unredeemable person. In The Merchant of Venice, Shylock still insists on retrieving his pound of flesh when Antonio is unable to repay the debt, and it is then settled in court. Shylock is so wounded and enraged by his feud with Antonio that it clouds his reason and judgement. As O’Rourke states, Shylock has ‘gone beyond trying to improve his own life; he can only imagine dragging his antagonists down to the level to which he has been reduced.’[59] In a similar tone, Mika Nyoni asks, ‘if one gets so much in terms of insults and his heart hardens as a result can we really blame him?’[60] The judge Portia sentences in Antonio’s favour and financially punishes Shylock. But even though Shylock has acted badly, it is obvious from the judge’s verdict that her disposition towards Shylock has been predetermined by the fact that he is a ‘Jew’ and ‘alien’:

Tarry, Jew.

The law hath yet another hold on you.

It is enacted in the laws of Venice,

If it be prove’d against an alien

That by direct or indirect attempts

He seek the life of any citizen,

The party ‘gainst the which he doth contrive

Shall seize one half his goods; the other half

Comes to the privy coffer of the state.[61]

The intent of Shakespeare was to simultaneously open a discussion about racial difference but reinstate the status quo at the resolution of the play. Further, Shylock seeks revenge well beyond the pain inflicted upon him, and this exaggerated response reinforces the notion that Shylock must be punished for his actions.

King and Hernandez Walta reappropriate Shelley and Shakespeare to once again question whether the outcast character seeking revenge is ever truly justified. This is proposed in the first volume when the narrator states that ‘Vin and Viv spent these days absorbing any information that they could acquire from outside sources. They found themselves often arguing over their interpretations, coming to blows once over whether Shakespeare’s Shylock was truly a villain.’[62] This reference allows readers to later interpret Vision’s and Virginia’s character transformations as problematic, because even though they can be empathised, their acts of vengeance are still morally wrong. Virginia is still held accountable for killing Mancha because, as the comic has repeatedly portrayed, there is a consequence for every action. In the aftermath, Virginia calls the investigating detective and claims responsibility for everything, then commits suicide and dies in Vision’s arms. Virginia protects Vision by not implicating him in his involvement in gaining access to Mancha. She does this so Vision can take care of their daughter, telling him that family is the most important thing in this world.[63] By Virginia dying, both her and Vision feel the consequences of their actions. Vision is now a grief-stricken widower and, having assisted in breaking into Mancha’s cell, will have to live with the responsibility of her death. Further, this is all a consequence of Vision’s initial decision to make a family, for he could not have foreshadowed when he created her that his wife could ever desire to die. As the narrator states, ‘what a shock then ... to discover that it was all beyond him.’[64] This means that Vision only ever created his family for himself without consideration for the actual people he conceived.

Page 37 of Volume 6 is a full-length panel of Vision holding his deceased wife, a distant voice captioned in the shadows: ‘Virginia did the right thing. Or she did the wrong thing. Or she just did what everyone does—.’[65] This reiterates the vulnerability of the Visions as humans because of their love and protection for their family unit in a sea of millennia families fighting for survival. This also reinforces the notion that revenge is what makes people human, even if those actions are monstrous, because Virginia ‘just did what everyone does.’ She protected her family under attack, and she avenged a child’s death. Much like Shylock has already argued, ‘if you wrong us, shall we not revenge?’ So, while Shylock, the creature and Virginia are all still accountable for their actions, the texts explore the notion of vigilante vengeance to recognise that people are not born bad out of their genetic differences. Rather, they are grown from bad seeds already woven into the fabrics of society.

6. Shakespeare Continued

Evidence that Director’s Cut pays homage to Shakespeare’s work is also in the alliteration of names—Vision, Virginia, Vin and Viv who live in Arlington, Virginia. It is no coincidence that The Merchant of Venice and Othello: The Moor of Venice are set in the same medieval city. Maurice Hunt has discussed Shakespeare’s thematic use of Venice as the setting for which he explores Othello and Shylock as racially excluded characters: ‘For this playwright, the name “Venice” denotes the place where these dynamics’ between the majority and the minority ‘can be described and explored.’[66] Similarly, Director’s Cut has deliberately alliterated the family’s names with their setting. Key to the story’s message is that Virginia shares the same name as the state, almost as if the comic is saying Virginia’s tragic demise is an iconic and metaphorical representation of the state itself. More importantly is the fact that they only lived ‘15 miles west of Washington, D.C.’ and that most of their neighbours worked in D.C. as ‘lobbyists and lawyers and managers.’[67] These are the same neighbours who harass and abuse the Vision family. Therefore, the authorial intent is to criticise the state and federal government.

Additionally, Hunt observes that Shylock and Othello are particular people begrudgingly needed by the Venetian state, because the former is of the religion that allows moneylending, and the latter is an extremely powerful combatant during a time when Venice is at war.[68] It is begrudging because they reluctantly accept what they need from the social outsider. As Hunt explains, ‘Venice’s commerce depends upon the usurious finance made possible only by the Jew, and the city’s unwarlike senators look elsewhere for the rugged general required to protect them from the Turk.’[69] This is also true to the role of Vision providing service to the United States as a superhero. When the family move to Virginia, Vision is assigned to be the president’s protector in the White House. However, the president makes it clear that although he depends on services that only Vision can provide, the synthezoid robot still remains a feared outsider: ‘Y’know, it’s funny. Meeting you, I’ve never felt so safe yet so scared. Isn’t that funny?’[70] To this, Vision can only reply, ‘yes, Mr President.’[71] The mistrust of Vision and his family is not only from the local community, but also from the highest form of leadership and representation of the United States law. Thus, these words from the president are resolute for how the family will be treated. Much like in The Merchant of Venice when Portia sentences Shylock, ‘the law hath yet another hold on’ the ‘Jew’ and ‘alien.’[72]

7. Conclusion

Vision: Director’s Cut proposes a new and complex perspective to numerous discussions. The comic works through the theme of otherness through the Visions as conscious synthezoids socially rejected by their community, and how this leads to a critique of human exceptionalism. Sentience and vulnerability prove the need to extend human rights. Kieran Tranter argues that ‘phenomenological studies, that is a focus on being-in the world, offers a way forward for the law and technology.’[73] Director’s Cut explores the state of being in the world that the Vision family experiences, and how this affects them as technological sentient beings subject under the law. Humanness is then also explored by asking what actions are considered ‘monstrous’ and what actions are considered ‘human.’ This exploration posits contradictory scenarios to which there are no clear answers. When Virginia rips Mancha’s heart out of his chest, she commits a monstrous act that proves her humanness. Simultaneously, Virginia’s act of vengeance must be held accountable by the law but is a grief-stricken action that any parent can understand.

Yet, the comic does not seek to provide an answer to all these debates. Rather, it leaves that for the readers to decide. The cliffhanger reinforces this authorial intention when Vision is creating his new robot family member and readers are forced to question whether this action is justified by his need for familial love, if not deemed a good or right decision. Perhaps readers must also be forced to reconcile that human life is messy and there are many problems for which there is no clear answer. As Vision says to Virginia, ‘the pursuit of an unobtainable purpose by absurd means is the way of freedom; this is my vision of the future. Of our future.’[74]

Perhaps it is only through the continual literary exploration of such questions that we can seek to come closer to a resolution. Shelley and Shakespeare also posit questions about humanness that do not have clear answers, and it is only through discussing and analysing these texts that we can hope to understand some truth. Thus, Director’s Cut has continued on this literary tradition as a step forward to this attempted resolution. Marvel Studios is scheduled to release a new television series called WandaVision, which is about the romantic relationship between Vision and Wanda Maximoff.[75] Marvel Entertainment released an accompanying statement with the advertising trailer that describes the new series as ‘a blend of classic television and the Marvel Cinematic Universe in which Wanda Maximoff and Vision—two super-powered beings living idealized suburban lives—begin to suspect that everything is not as it seems.’[76] Only time will tell whether WandaVision continues in this thematic literary tradition, examining not only questions of romantic togetherness, reality and illusion, but also acceptance of the ‘other,’ and the community of the human and non-human.

Bibliography

Primary Cultural Sources

Higgins, Kyle, Alec Siegel and Stephane Perger. Avengers Origins: Vision. New York: Marvel Comics, 2012.

King, Tom, Gabriel Hernandez Walta and Jordie Bellaire. Vision: Director’s Cut. Volume 1. New York: Marvel Comics, June 2017.

———. Vision: Director’s Cut. Volume 2. New York: Marvel Comics, July 2017.

———. Vision: Director’s Cut. Volume 3. New York: Marvel Comics, August 2017.

———. Vision: Director’s Cut. Volume 5. New York: Marvel Comics, October 2017.

———. Vision: Director’s Cut. Volume 6. New York: Marvel Comics, November 2017.

King, Tom, Michael Walsh and Jordie Bellaire. Vision: Director’s Cut. Volume 4. New York: Marvel Comics, September 2017.

Marvel Entertainment. WandaVision | Official Trailer | Disney+. YouTube video, 1:20. Released September 20, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sj9J2ecsSpo.

Russo, Anthony and Joe Russo, dir. Avengers: Infinity War. Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures. Released April 23, 2018.

Shakespeare, William. “Othello, the Moor of Venice.” In Complete Works of William Shakespeare, 1168–1209. Glasgow: HarperCollins, 1994, 2001.

———. “The Merchant of Venice.” In Complete Works of William Shakespeare, 149–180. Glasgow: HarperCollins, 1994, 2001.

Shelley, Mary. Frankenstein; Or, the Modern Prometheus. Boston: Sever, Francis, & Co., 1869.

Starlin, Jim, George Pérez and Ron Lim. The Infinity Gauntlet. 3rd edition. Volumes 1–6. New York: Marvel, 2011, 2016.

Whale, James, dir. Frankenstein. Universal Pictures. Released November 21, 1931.

———. The Bride of Frankenstein. Universal Pictures. Released April 19, 1935.

Whedon, Joss, dir. Avengers: Age of Ultron. Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures. Released April 13, 2015.

Secondary Sources

Bainbridge, Jason. “Beyond the Law: What Is So “Super” about Superheroes and Supervillains?” International Journal for the Semiotics of Law 30, no 3 (2017): 367–388. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196-017-9514-0.

———. “ ‘The Call to Do Justice’: Superheroes, Sovereigns and the State During Wartime.” International Journal for the Semiotics of Law 28, no 4 (2015): 745–763. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196-015-9424-y.

———. “ ‘This Is the Authority. This Planet Is Under Our Protection”—An Exegesis of Superheroes’ Interrogations of Law.” Law, Culture and Humanities 3, no 3 (2007): 455–476. https://doi.org/10.1177/1743872107081431.

Beauchamp, Gorman. “The Frankenstein Complex and Asimov’s Robots.” Mosaic: An Interdisciplinary Critical Journal 13, no 3/4 (1980): 83–94. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24780264.

Butler, Judith. Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex. New York: Routledge, 2011.

Capitanio, Adam. “ ‘The Jekyll and Hyde of the Atomic Age’: The Incredible Hulk as the Ambiguous Embodiment of Nuclear Power.” The Journal of Popular Culture 43, no 2 (2010): 249–270. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5931.2010.00740.x.

Curtis, Neal. “Doom’s Law” Spaces of Sovereignty in Marvel’s Secret Wars.” The Comics Grid: Journal of Comics 7, no 1 (2017): 1–24. http://doi.org/10.16995/cg.90.

———. “Superheroes and the Contradiction of Sovereignty.” Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics 4, no 2 (2013): 209–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/21504857.2013.803993.

Denson, Shane. “Marvel Comics’ Frankenstein: A Case Study in the Media of Serial Figures.” Amerikastudien / American Studies 56, no 4 (2011): 531–553. http://www.jstor.com/stable/23509428.

Giddens, Thomas, ed. Graphic Justice: Intersections of Comics and Law. Abingdon: Routledge, 2015. Accessed October 10, 2020. ProQuest Ebook Central.

———. “Natural Law and Vengeance: Jurisprudence on the Streets of Gotham.” International Journal for the Semiotics of Law 28 (2015): 765–785. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196-014-9392-7.

———. On Comics and Legal Aesthetics: Multimodality and the Haunted Mask of Knowing. Oxon and New York: Routledge, 2018.

Grear, Anna. “Embracing Vulnerability: Notes Towards Human Rights for a More-Than-Human World.” In Embracing Vulnerability: The Challenges and Implications for Law, edited by Daniel Bedford and Jonathan Herring, 153–174. Oxon and New York: Routledge, 2020. Accessed August 30, 2020. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Hunt, Maurice. “Shakespeare’s Venetian Paradigm: Stereotyping and Sadism in The Merchant of Venice and Othello.” Papers on Language & Literature 39, no 2 (2003): 162–184.

Johnston, Josephine. “Traumatic Responsibility: Victor Frankenstein as Creator and Casualty.” In Frankenstein: Annotated for Scientists, Engineers, and Creators of All Kinds, edited by David H. Guston, Ed Finn, Jason Scott Robert, Joey Eschrich and Mary Drago, by Mary Shelley, 201–208. Massachusetts and London: The MIT Press, 2017.

Kasturirangan, Rajesh and Krithika Srinivasan. “Political Ecology, Development, and Human Exceptionalism.” Geoforum 75 (2016): 125–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.07.011.

MacNeil, William P. “The Monstrous Body of the Law: Wollonstonecraft vs Shelley.” Australian Feminist Law Journal 12, no 1 (1999): 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/13200968.1999.11077291.

Nyoni, Mika. “The Culture of Othering: An Interrogation of Shakespeare’s Handling of Race and Ethnicity in The Merchant of Venice and Othello.” Theory and Practice in Language Studies 2, no 4 (2012): 680–687. https://doi.org/10.4304/TPLS.2.4.680-687.

O’Flinn, Paul. “Production and Reproduction: The Case of Frankenstein.” In Popular Fictions: Essays in Literature and History, edited by Peter Humm, Paul Stigant and Peter Widdowson, 196–221. Routledge, 2002.

O’Rourke, James L. “Racism and Homophobia in The Merchant of Venice.” ELH 70, no 2 (2003): 375–397. https://doi.org/10.1353/elh.2003.0020.

Peters, Timothy D. “ ‘Holy Trans-jurisdictional Representations of Justice, Batman!’: Globalisation, Persona and Mask in Kuwata’s Batmanga and Morrison’s Batman, Incorporated.” In Law and Justice in Japanese Popular Culture, edited by Ashley Pearson, Thomas Giddens and Kieran Tranter, 126–152. Oxon and New York: Routledge, 2018. Accessed October 10, 2020. Taylor & Francis.

———. “I, Corpenstein: Mythic, Metaphorical and Visual Renderings of the Corporate Form in Comics and Film.” International Journal for the Semiotics of Law 30 (2017): 427–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196-017-9520-2.

Siomopoulos, Anna. Hollywood Melodrama and the New Deal: Public Daydreams. New York: Routledge, 2012. Accessed October 27, 2020. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Szollosy, Michael. “Freud, Frankenstein and Our Fear of Robots: Projection in Our Cultural Perception of Technology.” AI & Soc 32 (2017): 433–439. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-016-0654-7.

Tranter, Kieran. “Nomology, Ontology, and Phenomenology of Law and Technology.” Minnesota Journal of Law, Science and Technology 8, no 2 (2007): 449–474.

[1] King, Vision: Director’s Cut (Vol. 1–6).

[2] See Bainbridge, “This Is the Authority”; Bainbridge, “The Call to Do Justice”; Curtis “Doom’s Law”; Curtis, “Contradiction of Sovereignty”; Giddens, Graphic Justice; Giddens, On Comics and Legal Aesthetics.

[3] Shakespeare, “Merchant of Venice,” Act 3, Scene 1, 259.

[4] Higgins, Avengers Origins: Vision.

[5] Higgins, Avengers Origins: Vision.

[6] King, Vision: Director’s Cut (Vol. 2), 5.

[7] King, Vision: Director’s Cut Vol. 1), 16.

[8] King, Vision: Director’s Cut (Vol. 1), 38.

[9] King, Vision: Director’s Cut (Vol. 1), 40.

[10] King, Vision: Director’s Cut (Vol. 1), 11.

[11] King, Vision: Director’s Cut (Vol. 1), 5.

[12] Kasturirangan, “Political Ecology,” 126.

[13] Grear, “Embracing Vulnerability,” 154.

[14] Starlin, Infinity Gauntlet, 119.

[15] Capitanio, “Jekyll and Hyde of the Atomic Age,” 249.

[16] Denson, “Marvel Comics’ Frankenstein,” 532.

[17] Bainbridge, “Beyond the Law,” 367.

[18] Peters, “Trans-jurisdictional,” 129.

[19] Giddens, “Natural Law and Vengeance,” 768.

[20] Giddens, On Comics and Legal Aesthetics, 7.

[21] King, Vision: Director’s Cut (Vol. 2), 30.

[22] King, Vision: Director’s Cut (Vol. 1), 21–22.

[23] King, Vision: Director’s Cut (Vol. 1), 23.

[24] King, Vision: Director’s Cut (Vol. 1), 23.

[25] King, Vision: Director’s Cut (Vol. 2), 8.

[26] King, Vision: Director’s Cut (Vol. 4), 42.

[27] King, Vision: Director’s Cut (Vol. 5), 22.

[28] Grear, “Embracing Vulnerability,” 171.

[29] King, Vision: Director’s Cut (Vol. 6), 19.

[30] Johnston, “Traumatic Responsibility,” 207.

[31] Szollosy, “Fear of Robots,” 433.

[32] Beauchamp, “The Frankenstein Complex,” 83.

[33] Shelley, Frankenstein, 101.

[34] King, Vision: Director’s Cut (Vol. 1), 5; King, Vision: Director’s Cut (Vol. 4), 15.

[35] Shelley, Frankenstein, 92.

[36] King, Vision: Director’s Cut (Vol. 6), 4.

[37] King, Vision: Director’s Cut (Vol. 4), 15.

[38] Shelley, Frankenstein, 116.

[39] Shelley, Frankenstein, 118.

[40] O’Flinn, “Production and Reproduction,” 210.

[41] O’Flinn, “Production and Reproduction,” 211.

[42] King, Vision: Director’s Cut (Vol. 3), 38.

[43] Siomopoulos, Hollywood Melodrama, 37.

[44] MacNeil, “Monstrous Body of the Law,” 21. For a closer understanding of violence on the body, see Butler, Bodies That Matter. For additional cultural legal readings of Shelley’s work, see Tranter, “Nomology, Ontology, Phenomonolgy,” 473–474; Peters, “I, Corpenstein,” 128.

[45] King, Vision: Director’s Cut (Vol. 1), 20.

[46] Grear, “Embracing Vulnerability,” 171.

[47] Whale, Bride of Frankenstein.

[48] Whale, Bride of Frankenstein.

[49] Higgins, Avengers Origins: Vision, 28.

[50] King, Vision: Director’s Cut (Vol. 6), 42.

[51] Whale, Bride of Frankenstein.

[52] Whale, Bride of Frankenstein.

[53] King, Vision: Director’s Cut (Vol. 1), 10.

[54] Shakespeare, “Merchant of Venice,” Act 3, Scene 1, 259.

[55] King, Vision: Director’s Cut (Vol. 3), 13.

[56] Shakespeare, “Merchant of Venice,” Act 1, Scene 3, 250.

[57] Shelley, Frankenstein, 174.

[58] Shelley, Frankenstein, 175.

[59] O’Rourke, “Racism and Homophobia,” 395.

[60] Nyoni, “The Culture of Othering,” 682.

[61] Shakespeare, “Merchant of Venice,” Act 4, Scene 1, 269.

[62] King, Vision: Director’s Cut (Vol. 1), 12.

[63] King, Vision: Director’s Cut (Vol. 6), 34.

[64] King, Vision: Director’s Cut (Vol. 3), 38.

[65] King, Vision: Director’s Cut (Vol. 6), 37.

[66] Hunt, “Shakespeare’s Venetian Paradigm,” 163.

[67] King, Vision: Director’s Cut (Vol. 1), 4.

[68] Hunt, “Shakespeare’s Venetian Paradigm,” 162.

[69] Hunt, “Shakespeare’s Venetian Paradigm,” 163.

[70] King, Vision: Director’s Cut (Vol.1), 12.

[71] King, Vision: Director’s Cut (Vol. 1), 12.

[72] Shakespeare, “Merchant of Venice,” Act 4, Scene 1, 269.

[73] Tranter, “Nomology, Ontology, Phenomonolgy,” 473–474.

[74] King, Vision: Director’s Cut (Vol. 1), 10.

[75] Please note, this article was submitted before the release of this new television series.

[76] Marvel Entertainment, “WandaVision.”

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/LawTechHum/2020/22.html