Melbourne Journal of International Law

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Melbourne Journal of International Law |

|

THE INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE IN COMPARISON: UNDERSTANDING THE COURT’S LIMITED INFLUENCE

The International Court of Justice in Comparison

Karen J Alter[1]*

The International Court of Justice (‘ICJ’) is the oldest international court in operation, with the authority to adjudicate cases raised by any United Nations member. It has the broadest jurisdiction of any international court, since states can designate or seize the ICJ to resolve disputes involving a broad range of interstate or international matters. The ICJ also has an advisory function, which can be used to clarify questions of international law. The potential for the ICJ to hear cases involving so many countries, treaties and issues means that the relative paucity of cases adjudicated across the ICJ’s nearly 75 years in operation is noteworthy. The traditional explanation for this paucity is that the ICJ lacks compulsory jurisdiction and that only states can initiate litigation. This article argues instead that the greatest limitation of the ICJ is its interstate nature. Part II provides an empirical overview that compares the ICJ’s docket to other international courts, and it explains why the dearth of ICJ litigation is consequential. Part III considers the ICJ through the lens of influencing state behaviour. Part IV moves beyond a state-centric focus to consider how international courts build authority vis-à-vis different audiences, including potential future litigants, the larger legal field and the public. Part V suggests that the ICJ’s limited influence is actually its greatest asset, since its very limits make the ICJ politically palatable. I therefore conclude that despite or perhaps because of its limitations, the ICJ is an indispensable international adjudicatory body, meaning that if it did not exist today, we would probably want to recreate its limited form anew.

Contents

This study uses the lens of comparing the International Court of Justice (‘ICJ’) to other international courts (‘ICs’) to gain insight into the ICJ’s strengths and limitations as an IC. A typical legal analysis focuses on formal competences and legal possibilities, examining constitutional texts, the larger organisational architecture or a small number of decisions. My research, by contrast, uses variation in the design, activation and influence of the world’s permanent ICs to understand when and how ICs influence domestic politics, state behaviour and international relations. I take an empirical rather than a legal or normative approach. Moreover, my approach is informed by social science understandings of when and how international law influences international and domestic policy and politics. As a political scientist, I approach the ICJ as a judicial actor embedded in a larger political context. I see international judges as legal strategists thinking about what the law requires, as well as how they can constructively engage compliance constituencies to help realise international law’s objectives.[1]

Part II of this article examines litigation trends at the ICJ, explaining how the ICJ differs in design and activation compared to other ICs. The data suggests a comparative dearth of ICJ litigation. This Part also explains why this dearth of litigation matters. The study then reflects on the ICJ through two different lenses that one might use to assess an IC’s influence and its legal and political power. Part III considers the ICJ through the lens of influencing state behaviour. Part IV moves beyond a state-centric focus to consider how ICs build authority vis-à-vis different audiences, including potential future litigants, the larger legal field and the public. This Part draws on a framework developed elsewhere, which explores how, when and where an IC’s authority is reflected in the practices of a range of different actors. Part V argues that the ICJ’s limits are its greatest asset. Part VI concludes.

This article focuses on what we can learn by applying theory and comparing the ICJ to other ICs. This analytical strategy is common in social science, which explores variation and uses metrics, theories and ideal types to generate hypotheses and reveal generalisable insights. Social science methods generally undervalue what many lawyers value most — the ICJ’s ability to develop international law and provide precedents that they can use. Moreover, lawyers understandably prefer a case-by-case mode of analysis because if their case is the exception, their particular outcome is what matters most. Yet finding an exception does not falsify a larger claim. In fact, social scientists expect exceptions to exist.[2]

The larger argument in this short article is that the ICJ is a unique although not unrivalled body when it comes to interstate dispute settlement. Yet its ability to help enforce international law, to adjudicate the larger constitution of international law or to be a review body for the United Nations’ actions is hampered by its interstate nature. One might say that the ICJ is hobbled by design, since many governments mostly want the ICJ to resolve interstate disputes when so requested. For a body often called the ‘World Court’, one can ask why the preferences of governments should determine the extent of the ICJ’s authority and influence. Indeed, neither ICJ judges nor the ICJ’s larger audiences are satisfied with this narrow perspective. What does it mean for international law that the ICJ seems to be hampered by design? My answer is that the ICJ’s structural limitations are its strength, as these limitations make the ICJ a palatable option for recalcitrant states. To be sure, one could imagine reforms that would improve the ICJ’s operation and influence in the UN system. Yet because there is a real benefit in having a focal global legal institution that all countries can recognise and embrace, if the ICJ did not already exist as a permanent IC, we would want to recreate it anew, replicating the structural limitations that contain the ICJ’s influence and effectiveness and thereby make it politically acceptable.

The ICJ is the oldest permanent IC in operation. Founded in 1945 as part of the UN, the ICJ is a continuation of the League of Nations’ Permanent Court of International Justice (‘PCIJ’), which operated between 1922 and 1946.[3] Often called the World Court, the ICJ was intended to play a pivotal role in the international institutional infrastructure of the post-World War II world order.

Imperial powers had been experimenting with international adjudication of disputes since the 1800s.[4] Participants in the various Hague conferences at the turn of the 19th century imagined a world in which power politics would be subordinated to international law and disputes would be peacefully resolved through diplomacy or international adjudication.[5] Some legal diplomats envisioned the creation of a set of ICs for the UN system, including an international criminal court, an international terrorism court and an international prize court.[6] This objective may have always been fanciful, but many, if not most, of the global institutions negotiated in the 1940s envisioned a role for the ICJ. What this role would be varied across institutions, and seldom was the ICJ given exclusive jurisdiction. For example, the Constitution of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization[7] allowed for references to the ICJ or an arbitral tribunal.[8] The Constitution of the World Health Organization allowed any dispute concerning the Constitution to be referred to the ICJ, but it also envisioned negotiations to resolve disagreements, and it allowed the parties to choose other methods of dispute settlement.[9] The International Labour Organization expected disputes to first be resolved by a Commission of Inquiry, yet noncompliance with Commission decisions could be appealed to the ICJ, whose decision would be final.[10] The fully negotiated charter to establish the International Trade Organization allowed organs of the organisation to request an advisory opinion regarding the charter.[11] Openly discussed and left open was the idea that these advisory opinions could involve factual assessments and monetary remedies.[12] The larger point is that the new global order included the ICJ as a judicial branch.

These discussions, and the Charter of the United Nations, established a very broad potential jurisdictional reach for the ICJ. Indeed, compared to all other ICs operating today, the ICJ has the broadest potential jurisdictional reach. The ICJ has authority to adjudicate cases raised by UN member states (51 at its founding and 193 today), albeit only if the parties textually or substantively consent to the ICJ’s jurisdiction over the dispute.[13] Cases can include any legal question, including requests for provisional measures and questions about remedies owed. A treaty — bilateral or multilateral — can designate the ICJ as the final adjudicator of disputes related to the treaty. In 2007, the ICJ reported 268 treaties where it was designated as the final adjudicator of disputes.[14] In addition, in principle, all UN organs, including its specialised agencies, can request an advisory opinion regarding legal questions related to a UN organisation’s mandate and operations.[15]

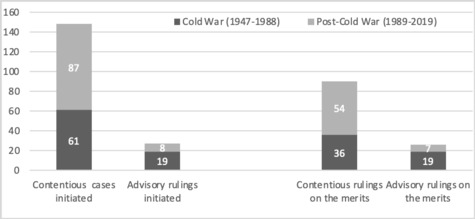

This list of the types of cases that the ICJ can be called upon to adjudicate is expansive, yet if one considers the total number of states, UN institutions and treaties adopted, it is clear that this jurisdictional potential is seldom realised. The ICJ is adjudicating more cases today compared to 20 years ago.[16] Yet, given the potential for the ICJ to hear cases involving so many countries, treaties and issues, the relative paucity of cases adjudicated across the ICJ’s nearly 75 years of operation is noteworthy. Figure 1 considers de novo cases that were filed in the ICJ, dividing the case load into the less active Cold War period and more active post-Cold War period.[17] On the left are de novo cases that were initiated, and on the right are rulings on the merits. For contentious cases, the difference between cases initiated and rulings on the merits indicates that cases were settled or withdrawn or that the ICJ determined either that it lacked jurisdiction or that the case did not qualify as a dispute. There can be interim rulings about admissibility, jurisdiction and procedure, calls for provisional measures and for reviews or reinterpretations of previous decisions — so Figure 1 does not reflect the total work of the ICJ. Indeed, the Special Issue’s category of ‘encounters’ might be better represented by ICJ’s unfiltered general list (178 cases) and perhaps also third-party interventions and calls for reinterpretations. Figure 1 does, however, speak to state demand for the ICJ’s involvement in adjudicating disputes and questions of law and the ICJ’s caution in claiming jurisdiction.

Figure 1: ICJ Caseload 1946–2019

Based on updated data from Karen Alter, The New Terrain of International Law: Courts, Politics, Rights (Princeton University Press, 2014).

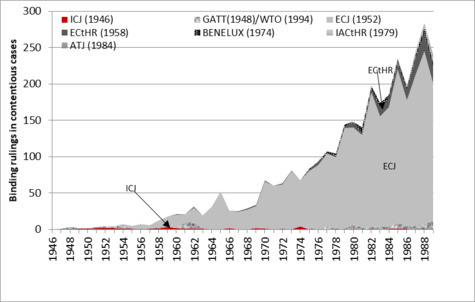

I will return to the issue of advisory opinions in Parts III and IV, but the rest of this Part focuses on contentious cases. Figure 2 considers the distribution of cases over time and in comparison to other operating ICs. Figure 2 demonstrates that the European Court of Justice (‘ECJ’) and the European Court of Human Rights (‘ECtHR’) were, from the outset, the two busiest ICs. Before the end of the Cold War, the five remaining permanent ICs plus the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (‘GATT’) system issued only 217 binding rulings in contentious cases. The oldest court in this list — the ICJ — issued just 36 rulings on interstate disputes between 1946 and 1988 (and gave 19 advisory opinions).[18]

Figure 2: Rulings by International Courts during the Cold War, per Year (Year of First Ruling)

Data from Karen Alter, The New Terrain of International Law: Courts, Politics, Rights (Princeton University Press, 2014). Includes only binding rulings on the merits. ECJ = European Court of Justice; ECtHR = European Court of Human Rights; IACtHR = Inter-American Court of Human Rights; ATJ = Andean Tribunal of Justice.

The presence of cases over time matters, because having a steady docket allows judges to gain experience from working together and dealing with a range of issues. A sparse docket, where cases are spread across significant periods of time, and where there are few substantively similar cases, makes it hard, if not impossible, for an IC to use incrementalism to build its jurisprudence.[19] Cases also provide international judges with opportunities to connect with nationally based legal interlocutors and thus to have national encounters. Where countries and actors engage rarely with an IC, international judges may lack the resources or opportunity to build relationships and project externally focused judicial outreach that connects with domestic legal and political audiences.[20]

The creation and use of ICs took off in the post-Cold War period.[21] The design of ICs changed as well. I gave the name ‘old-style’ to ICs that lack compulsory jurisdiction and that only allow states to initiate binding litigation. These two features matter together. An absence of compulsory jurisdiction allows actors that do not have law on their side to block litigation from proceeding. Limiting access to states also matters, because states have many means available to resolve disputes, and states are generally loath to cede interpretive and adjudicative control to independent judges. Setting aside its advisory jurisdiction, the ICJ is the canonical old-style IC, which also means that it is increasingly exceptional rather than modal for an IC.[22] Most ICs today are ‘new-style’, meaning that they are ICs with compulsory jurisdiction and access rules that allow non-state actors to initiate litigation. New-style features matter because non-state actors — including private litigants and international institutions — are more likely to initiate litigation and raise a broader range of cases and legal questions either because they may have few other means of redress, because the litigants want to help develop international law or because the instigator’s institutional mandate includes investigating and pursuing violations of the law.[23] Knowing that litigation is likely and cannot be blocked, state defendants that do not have the law on their side are incentivised to negotiate and settle, to avoid an adverse ruling that can generate a legal precedent. In other words, new-style features shape both the docket and the incentive to settle out of court.

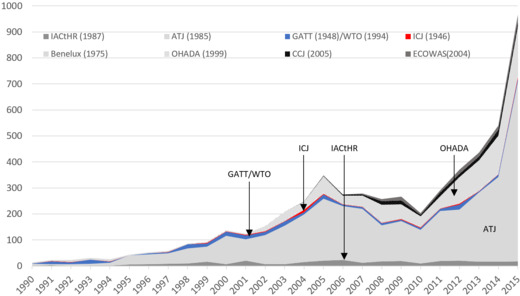

Figure 3 compares binding rulings on the merits by the most active ICs during the post-Cold War era, excluding the ECJ and the ECtHR to make the figure more readable and excluding the International Criminal Tribunals for Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia because they are no longer operational.[24] The two interstate ICs in this figure are the GATT/World Trade Organization (‘WTO’) and the ICJ, both denoted in bright colours. A common explanation for why few disputes reach the ICJ is its lack of compulsory jurisdiction.[25] Less than one third of UN members have made an optional declaration under art 36(2) of the Statute of the International Court of Justice recognising the compulsory jurisdiction of the Court.[26] Figure 3 suggests that the larger impediment may be the requirement that only states can initiate litigation. The ICJ shares with the GATT’s successor, the WTO, the limitation of access for the initiation of litigation to states. In the WTO, which now has 163 members, panels issued 243 decisions (from the 501 cases that were initiated).[27] The ICJ issued 51 rulings on the merits in contentious cases (89 cases were initiated). The data for the ICJ is difficult to see because it is relatively small by comparison. Meanwhile the new-style legal bodies were all more active, as indicated by the height of band for each court.[28]

Figure 3: Post-Cold War Rulings by the Most Active International Courts, per Year (Year of First Ruling), 1990–2015

Based on updated data from Karen Alter, The New Terrain of International Law: Courts, Politics, Rights (Princeton University Press, 2014). Includes rulings on the merits only. See footnote 28 for litigation rate sums.

Of course, the goal of a legal system is not to have a lot of cases. One might even argue that the most effective IC would have no cases, because there would be no violations of law to adjudicate. Activity is, however, correlated with demand for legal interpretations. Given the ambiguity of many international legal rules and the prevalence of noncompliance with the international agreements that these courts oversee, one can believe that the significantly smaller number of cases adjudicated by the ICJ and the WTO correlates with state reluctance to use litigation to resolve disputes. This point will be important for the discussion in Part IV, which focuses on the broader authority of ICs.

To be sure, litigation rates are not a proxy for court importance. Counting cases raised and adjudicated underestimates the extent of national encounters in that it does not capture ‘a wide range of interactions between the ICJ and its regional and national publics’.[29] Comparing dockets can also overestimate ICs’ legal and political relevance, since not all legal rulings are substantively, legally or politically important. Indeed, no one would argue that the Andean Tribunal of Justice — the third most active IC with 2,853 rulings between 1984 and 2015 — is more important than the ICJ.[30] One might even claim that the ICJ is one of the most important and impactful ICs because it rules on important issues, because journalists and international officials pay attention to these rulings, because legal scholars regularly teach and cite ICJ rulings and because government officials often look to ICJ jurisprudence for guidance. These concerns raise the challenging question of how we should assess the significance of a court and its rulings.

One way to think about the complexity of this issue is to consider the ICJ’s ruling in Military and Paramilitary Activities in and against Nicaragua (‘Nicaragua’).[31] Notwithstanding that the United States did not participate in the merits phase adjudication of its use of force in Nicaragua, the ICJ ruling was front-page news in the US.[32] The Nicaragua ruling is regarded as important in defining international law on the use of force. For example, Anthea Roberts generates word clouds of cases discussed in American and British textbooks, and the Nicaragua decision figures prominently.[33] ICJ supporters also see the Nicaragua ruling as important in demonstrating that law, rather than power, determines outcomes at the ICJ.[34] But if the measure of effectiveness is the ability of an IC or decision to induce states to change their behaviour in a more law-compliant direction, then it is harder to make a case for this decision’s positive impact. Critics of the ruling see its primary impact in encouraging the US to withdraw from its declaration accepting the ICJ’s compulsory jurisdiction.[35] Other critics suggest that the ruling demonstrated the powerlessness of the ICJ.[36] The ruling surely incited the wrath of the American conservative right, making them permanently hostile to international law and international adjudication.[37] In trying to trace the impact of the ruling in real time, I found that the ruling arguably contributed to shifting a few key votes against Congressional support of aid to the Nicaraguan Contras. This is an important impact because it was the very first Congressional vote against providing Contra aid, and influencing US support for Contra aid was a key objective for the American lawyers involved in the case.[38] This influence is, in my view, more significant than the fact that, years later, the US got Nicaragua to settle the dispute in exchange for foreign aid.[39] But even if the Nicaragua case generated the short-term win that its advocates desired, the critics might be right about the ruling’s long-term impact. According to Roberts, in China, the Nicaragua decision is discussed in the context of China following the US in boycotting the adjudication of non-consensual disputes.[40] Meanwhile, the ICJ’s ruling may have had a favourable impact in Latin America, where numerous countries have turned to the ICJ to resolve various disputes.[41]

The upshot of this Part is that a lack of cases hinders the ICJ’s ability to develop the content of international law and its ability to strategically connect with domestic interlocutors. The discussion of the Nicaragua case further raises the question of how we should think about the ICJ’s influence in the cases that it adjudicates. The Nicaragua case may have enhanced the ICJ’s reputation for judicial independence without harming the US’s reputation resulting from ignoring the Nicaragua ruling; it may have influenced US domestic politics without meaningfully influencing US policy or the substantive outcome for legal issue at hand; it may have contributed to developing international law on the use of force, but it also generated the precedent of how powerful countries can undermine the legitimacy of an ICJ ruling by not participating and continually protesting the legitimacy of the ruling. The next two Parts build on this analysis to consider different ways that the ICJ could be influencing international law and state adherence for this body of law.

This Part considers the ICJ through the lens of influencing litigating state behaviour, identifying three causal pathways through which the ICJ might influence state parties to the dispute. It then analyses the challenges that the ICJ faces in using the multilateral and transnational pathways, concluding that the ICJ is best able to influence states by serving as an interstate arbiter that expresses international law.

It matters if international judicial rulings generate compliance, yet social scientists know that compliance is actually the wrong metric to assess international institutional influence.[42] The problem with compliance as a metric is that international agreements can ask states to change little to nothing, which will lead to an inflated finding of full compliance. Meanwhile, agreements that ask for large changes and then garner less than 100% compliance might be faulted for not achieving full compliance, even though the impact of the ambitious agreement is greater compared to the impact of a shallow agreement that asks little.[43] This problem applies to international judicial rulings as well, which is why most social scientists — myself included — adopt the metric of effectiveness, meaning change in the direction indicated by the law.[44]

The New Terrain of International Law identifies three very different ideal types that scholars use to imagine how and why judicial rulings can influence the behaviour of states. In the interstate arbiter ideal type — adopted most commonly by rational choice and law and economics scholars — international judicial rulings serve an expressive function that provides information. The ruling does not change underlying state preferences, but it does construct a focal point around which litigating parties can converge. The multilateral politics ideal type — adopted by international relations scholars who study multilateralism, by scholars who believe that a state’s international reputation for law compliance is important and by scholars who conceive of ICs as trustees of an international agreement[45] — sees international judicial rulings as being able to shift the meaning of international law and state preferences. An international judicial ruling becomes effective when and because a majority of states prefer the international legal interpretation endorsed by the IC, so the cost-benefit analysis of non-complying states changes, pushing the non-complying state in the direction of respecting the international law as interpreted by the IC. The transnational politics ideal type sees international judicial rulings as shifting domestic political debates, altering a state’s behaviour from within. The point of identifying these approaches is to help us think about the pathways towards compliance, but all three approaches to encouraging states to change their behaviour can and do work, so it is pointless to debate which approach is better or more correct.[46] What matters is that these different approaches generate three different means of generating compliance: by providing information, by shifting a state’s international cost–benefit analysis or by scrambling internal domestic political calculations in ways that shift the preference of a governments.[47] This Part considers the ICJ’s ability to influence state behaviour via these three modalities. This discussion applies to both contentious cases and to advisory opinions, so long as the goal of adjudication is to influence state policy or behaviour.

The interstate arbiter ideal type imagines two state parties consenting to bring a dispute to an IC for resolution. In issuing its ruling, the court expresses the law, providing information and a legal endorsement that is helpful to the litigating parties. This is the model posited by Eric Posner and John Yoo, who suggest that ICs can only be effective if they follow this fully consensual model.[48] The informational influence of ICs is typically explained in terms of parties using the legal process to ratify a decision they have already made, to shift the blame to a court or to legitimise an action that might otherwise provoke domestic opposition. These arguments suggest that there is no actual change in a state’s preference. The expressive nature of the IC ruling merely helps a government accomplish what it already wanted to do, which was to defer to international law to resolve the dispute. A ruling may also construct a core legal precedent that states may embrace going forward.[49]

Especially because the ICJ has a limited compulsory jurisdiction, one might think that most ICJ cases fit into this consensual interstate arbiter model. Yet according to Cesare Romano, ‘only one out of seven cases put on the ICJ docket [between 1947 and 2007] has been submitted by way of agreement between the parties’.[50] Even if the parties do not pre-consent to adjudication, the process of adjudicating the dispute may still bring parties together. Indeed, Martin Shapiro suggests that adjudication involves many techniques to elicit consent on behalf of the litigating parties.[51] Both the pre-consent and the eliciting consent approaches fit the interstate arbiter model, wherein international judges seek an outcome that can unite or bring the litigating parties to a resolution.

Even though the ICJ can assert jurisdiction despite a respondent state’s protest, the interstate arbiter pathway to compliance may be the best suited mode for the ICJ to influence state behaviour. To be sure, nothing prevents actors who were not part of the initial dispute from drawing on ICJ interpretations as they negotiate with their own government or with other states. Yet there are relatively few instances where states raise a copycat case in the expectation of receiving a similar legal determination. Compared to ICs with a more limited jurisdiction and crowded docket, the ICJ tends to rule infrequently and on a broad range of legal cases. If each case is completely distinct from another, and if a country appears before the ICJ rarely, then it is hard to see present compliance with an ICJ ruling as an indicator of future compliance with an ICJ ruling. In this respect, a reputation for general compliance may not shape state decisions regarding ICJ rulings. The lack of copycat cases will also become relevant in Part IV when I consider the challenges of the ICJ in establishing ‘intermediate authority’, meaning authority vis-à-vis similarly situated litigants.

Part of the reason why there are so few copycat cases is that ICJ adjudication is easily blocked or thwarted, which is another way of saying that the ICJ’s lack of compulsory jurisdiction hinders the filing of cases. Indeed, states regularly challenge the jurisdiction of the ICJ, and quite often these challenges succeed, in part because the ICJ has non-exclusive jurisdiction, but also because the ICJ sometimes finds additional requirements within the texts of the specific agreements it is asked to interpret. These alternatives to adjudication combined with the fact that ICJ rulings are not enforceable give considerable stonewalling leverage to the country that does not want to change its policy.

It is also worth noting that the ICJ mostly lacks access to the multilateral and transnational modes of influencing state behaviour. The multilateral politics pathway requires that states converge around the IC’s legal interpretation, so that the non-complying state cannot negotiate a change in the underlying legal rule and its continued noncompliance brings international costs. For bilateral agreements, states can negotiate a change in the underlying rule. Sometimes states unite to pressure a state on the losing end of an ICJ ruling to change its behaviour, but most ICJ disputes do not implicate other states, and international pressure may not be enough to encourage a recalcitrant state to change course. In principle, the UN Security Council could step in to enforce an ICJ ruling.[52] In practice, this seldom occurs. In short, although the Security Council could encourage states to use the ICJ more and help enforce ICJ rulings, in reality, it is not an ally promoting the relevance or importance of the ICJ within the UN system.[53]

Can domestic politics, and thus the transnational politics model, provide a pathway encouraging compliance with an ICJ ruling? Sometimes an ICJ ruling can influence domestic politics, as mentioned in Part II’s discussion on the ICJ’s ruling on the US’s illegal use of force in Nicaragua.[54] There is great variation in when and whether domestic actors will mobilise to support ICJ rulings. Overall, and especially outside of the realm of protecting human rights, it is rare for a national judge to lend their support to enforcing IC rulings. This is especially so with respect to the ICJ, given that the ICJ exercises a jurisdiction that domestic supreme courts lack.[55] That said, whether a specific country’s loss at the ICJ generates a domestic pressure to comply is an empirical question that can vary by case and country.

The reality that collectivities of states and domestic compliance constituencies rarely unite to support the ICJ affects decisions to litigate and the ICJ’s behaviour in cases that are litigated. States that put a premium on respecting international law may be swayed by ICJ legal precedents, and invoking an ICJ precedent can help to legitimate a state action. But politicians also understand that they can effectively stonewall and ignore the ICJ. Those actors who could trigger the ICJ advisory function may therefore hesitate to request an opinion that will then be rejected or ignored, or that the ICJ may dismiss for want of legal relevance and thus legal standing.[56] The ICJ is left searching for ways to uphold international law and build state consent for its rulings.

This Part’s analysis further underscores that the interstate nature of the ICJ may be the greatest limitation on what the ICJ can accomplish. States conceive of the ICJ as a dispute settlement body only; while there are some notable exceptions, states rarely raise cases purely for the goal of developing international law.[57] So, even if the ICJ had compulsory jurisdiction, it would still find its role limited by the non-exclusive nature of its jurisdiction, the reality that states see the ICJ as an interstate dispute settlement body, and the fact that neither collectivities of states nor important domestic interlocutors will consistently lend their support to help enforce ICJ rulings upon contentious cases.

To focus on how ICJ rulings influence states is a very limited way of thinking about the influence of ICs in international politics and across a legal system. This section moves beyond a state-centric focus to consider how ICs build authority vis-à-vis different audiences, including potential future litigants, the larger legal field and the public. Drawing on a framework developed in the book International Court Authority, this Part gets closer to the ‘national encounters’ perspective of this Special Issue. The analysis suggests that the ICJ is able to connect to the legal field of international lawyers, but there are many ways that recalcitrant states can avoid following the ICJ if they so choose. These realities limit ‘national encounters’ and again underscore how, compared to other ICs, the ICJ’s interstate nature limits its influence.

In International Court Authority,[58] Laurence R Helfer, Mikael Rask Madsen and I develop an authority metric that can be used to assess an IC’s growing and diminishing authority over time and across space.[59] The metric focuses on de facto as opposed to de jure authority in order to capture recognition of an IC’s authority by diverse audiences.[60] We develop a conjunctive standard to measure IC authority that involves actors recognising a legal ruling as binding and taking meaningful action to encourage compliance with the ruling. We consider five different levels of authority. The first level, no authority in fact, describes an IC that is inactive despite known violations of the law or an IC that issues decisions that are widely ignored. Narrow authority exists when the litigants to the dispute both accept a ruling as legally binding and take consequential actions towards giving it effect. Intermediate authority exists when this conjunctive standard of recognition and meaningful action extends to potential future litigants, government officials and national judges. Extensive authority exists when this standard is met by a wider field that includes both legal actors (eg bar associations, law firms and scholars) and non-legal actors (eg civil society groups) who engage and seek to influence actions and legal understandings. A final level, popular authority, exists when an IC’s rulings are viewed as binding and trigger consequential changes in behaviour among the public at large, including the major participants in public debates (eg politicians, the news media and activists).[61]

Using words like ‘level’ of authority suggests that an IC’s de facto authority exists along a continuum from narrow to extensive to popular authority. In fact, the categories correspond to different audiences, and the levels are independent of each other.[62] An IC may or may not gain authority across the full spectrum of audiences. For example, a court may have extensive authority, in that its rulings are treated as binding and as requiring meaningful action by scholars, civil society groups and legal practitioners. However, those same rulings may lack narrow authority because they are ignored by the parties to the dispute, or they lack intermediate authority because, while respected by the parties, they are disregarded by similarly situated litigants and government officials.[63] De facto authority can also vary by issue and by country; a court can have narrow, intermediate or extensive authority across the full range of disputes and states subject to its jurisdiction, or such authority can be confined to specific policy domains or subsets of states.[64]

By thinking of IC influence across various audiences, we can start to think about the larger power of ICs to influence the body of international legal jurisprudence, domestic policy debates and international relations. In theoretical terms, the metric is a practice-based assessment of IC influence.[65] As we explain:

Conceptually, this means that IC authority is not a top-down ordering imposed by the grant of de jure authority, the edicts of governments, or the orders of judges; it is instead the result of the relative internalization of IC decisions or interpretations in the practices of legally, socially, and politically situated audiences.[66]

Our larger claim is that the de facto ‘authority of an IC — and its variability — must ... be measured by the ways in which a court’s judgments are reflected in the practices of audiences in the short and medium term’.[67] An IC develops its authority by adjudicating and thus by pronouncing a potentially applicable precedent that applies to a range of legal issues. An IC also builds its authority by gaining intermediate and extensive authority across a range of actors and issues and in a range of countries.[68]

Part II mentioned that ICJ rulings are few and far between and that few repeat players and copycat cases appear on the ICJ’s docket. Part III illustrated that the ICJ can be said to have narrow authority, through consideration of the ICJ in its interstate arbiter role. Part III also explained how the UN Security Council and national supreme courts are not reliable allies when it comes to exhorting or pressuring governments to follow ICJ rulings. The lack of pressure from copycat cases or compliance supporters does not on its own mean that the ICJ lacks intermediate authority and thus influence over similarly situated litigants (in other countries). Indeed, international diplomats readily recount that invoking an ICJ precedent can be useful, and one can imagine that an adverse ICJ ruling could generate pressure on a state to change an ‘illegal’ practice that is replicated in other locations. But isolated examples are insufficient to create an erga omnes influence, wherein ICJ rulings would be seen as creating legal obligations owed to all. Also undermining a larger intermediate authority is art 59 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice specifying that ‘[t]he decision of the Court has no binding force except between the parties and in respect of that particular case’.[69] This formal rule provides an escape hatch for governments looking for ways to avoid or minimise certain international legal obligations.

The ICJ’s best chance of widening its audiences is via its extensive authority, meaning its authority vis-à-vis legal scholars, bar associations and civil society groups. Presumably the ICJ’s advisory opinion role is well suited to building the ICJ’s extensive authority. In its advisory function, the ICJ can receive requests from a number of UN linked agencies for non-binding interpretations of international law.[70] To be sure, the ICJ has issued a number of important advisory opinions that have contributed to the specification and development of international law. Scholars and practitioners have imagined how the advisory role might be used to police UN actions or to provoke UN bodies to act when they fail to act[71] and how this role could be helpfully expanded.[72] The UN General Assembly has referred controversial cases — such as Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory — that states party would probably not pursue to the ICJ.[73] Yet because states often react poorly to efforts to use the advisory role in expansive ways, the ICJ appears hesitant to embrace legal efforts to cajole it beyond a narrow and fairly formalist interpretation of its advisory decision function. Legal scholars seem to mostly accept the ICJ’s reticence, framing their concerns in legal terms such as concerns that the ICJ will lack key factual information, that it will be unable to fulfil due process requirements or that the ICJ needs to protect its ‘judicial character’.[74] The failed efforts to formally expand the ICJ’s advisory role[75] and the ICJ’s own reticence to embrace the opportunities and encouragement of certain states, international actors and scholars suggest again that the ICJ’s interstate nature is the fundamental factor limiting the ICJ from self-expanding its advisory mandate and jurisprudence.

The ICJ’s relatively small case load and its lawmaking reticence have practical implications. Fewer cases mean fewer opportunities for bar associations, legal advisors to national politicians, and lawyers to engage with the ICJ, and thus fewer incentives for the wider legal community to specialise in ICJ case law. Indeed, the number of legal actors with experience litigating before the ICJ is extremely small. Compare, for example, the ICJ to the WTO’s dispute settlement system. There is no advisory role in the WTO system, and only states can initiate litigation in the WTO system. But states have formed public–private partnerships wherein industry has an incentive to hire lawyers to build cases that they can present to state agencies engaged in WTO litigation. It is both easy to imagine, and to document, how lawyers are monitoring WTO panel rulings and advertising their services to industries and governments in ways that mobilise lawyers, scholars and claimants to extend the influence of WTO law.[76]

The ICJ’s best chance of building extensive authority is to connect with civil servants working in governments, with civil society groups who might amplify how state actions violate international law and ICJ rulings and with members of the legal academy engaged in international law. This is the hope animating the ‘national encounters’ approach, namely a hope that interactions will breed familiarity, building (positive) relationships between domestically based lawyers and civils servants, and the ICJ. To be sure, ICJ judges regularly engage these audiences, and international legal scholars often teach ICJ rulings to their students. But again, the reality — that (a) as a formal legal matter, ICJ rulings are not binding beyond the parties to the case and the dispute that is litigated; (b) states rarely avail themselves of their right to litigate at the ICJ; and (c) great powers react poorly to efforts to expand the ICJ’s contentious and advisory dispute settlement functions — means that, as a practical matter, the larger legal field of lawyers, scholars, bar associations and other legal practitioners need not seriously consider how ICJ precedents will be relevant in their legal practice and professional lives.

With neither intermediate nor extensive authority, it is hard for the ICJ to establish popular authority. Journalists and political opponents may draw on ICJ precedents to criticise alleged illegal behaviour, but as the earlier discussion of the Nicaragua ruling showed, these invocations may not decisively sway public opinion or impact the domestic or international reputation of the government.

There is one silver lining to be found. Although the ICJ issues relatively few rulings compared to the far reach of its de jure authority, the ICJ has ruled on a diverse range of legal issues. With the possible exception of the ECJ and the ECtHR, no other international legal body has pronounced on as many diverse legal issues, ranging from issues pertaining to the drawing of territorial boundaries to genocide and the use of force. The ICJ also adjudicates cases that involve states that would otherwise not fall under the jurisdiction of any IC. For example, the ICJ is the only international judicial institution to hear cases involving Islamic states.[77] For journalists and scholars interested in what international law means for countries that do not fall under the jurisdiction of regional courts and for issues that only the ICJ has addressed, ICJ rulings may provide the best guidance.

This discussion again underscores how the interstate nature of the ICJ limits its influence and authority. This reality exists, but the ICJ is nonetheless an indispensable IC.

The old terrain of international law involved international adjudicators providing dispute settlement to assist state and non-state litigants to resolve disputes that span borders. This important role may be what the ICJ can best provide. A challenge that the ICJ faces is that there is considerable competition in fulfilling this role, since there are so many ways to resolve disputes that span borders, including diplomatic negotiation, good offices, mediation, binding arbitration, discussion in committees or deliberative bodies of international organisations and international adjudication. Only the ICJ can both resolve disputes and help define and develop international law along the way, which together with its global salience may make the ICJ a relatively less attractive dispute settlement body for a national government. In any event, it is hard to build an international judicial system exclusively around an interstate dispute settlement role.[78]

In The New Terrain of International Law, I discuss additional roles that new-style ICs play. ICs can also help enforce international law, provide administrative review of the application of international rules by international agencies and relevant domestic agencies, and provide constitutional review of the legality of domestic and international actions.[79] These other roles provide ICs with cases to adjudicate, and they allow an IC to help develop the body of law they oversee. As I explain in that book, these roles were explicitly delegated to new-style ICs.[80] Indeed, non-state actors were authorised to initiate litigation and to challenge state or international actions and non-actions precisely for these purposes. Moreover, these are not hypothetical roles. The New Terrain of International Law includes numerous examples of ICs providing administrative review, helping to enforce international law and providing constitutional review. In a deeper study of the Andean Tribunal of Justice (‘ATJ’), Larry Helfer and I further demonstrate how the ATJ plays all of these roles, helping to enhance respect for Andean law despite the economic and political turbulence in the Andean region.[81]

In principle, the ICJ could be called upon to fulfil all of these roles. States can ask the ICJ any question about international law,[82] yet most of the questions posed are limited to questions of law and fact related to the case at hand. In theory, the ICJ could play an administrative review and constitutional role if its advisory jurisdiction were actively engaged by UN bodies and specialised agencies. But, as Parts II and IV demonstrated, the court’s advisory role is rarely invoked, and the ICJ is hesitant to embrace efforts to expand its advisory function. This reality means that the ICJ is unable to play a larger role enforcing international law, developing international law or serving as a constitutional arbiter within the UN. This leaves the UN system without a robust judicial branch. The de jure authority exists, but the de facto authority is missing.

The ICJ’s uniquely limited nature may, however, be its greatest asset. For countries that have not acceded to the authority of regional courts (41 in total), and for countries that are part of the WTO adjudication system but no other global courts (30 countries, including the US, Israel and China) — thus a substantial number of countries in the world — the ICJ is the only global court that they could possibly engage.[83] For these countries, the non-threatening nature of the ICJ, which in part means the ability of states to successfully contest the ICJ’s jurisdiction and the reality that ICJ rulings only pertain to the case at hand, is the ICJ’s greatest attraction. To the extent that authoritarian governments reject robust judicial review, the ICJ may be the primary, if not the only, international legal institution for disputes involving non-democratic governments.

If the ICJ is the international legal body where democracies and authoritarian countries alike work together to resolve their disputes, then it makes sense to keep the ICJ’s role circumscribed. In this sense, the ICJ’s judicial strategy of hewing closely to the law, so that its interpretations will be recognised as legal and legitimate by diverse countries, may be a wise approach. This legal formalist strategy frustrates those who would like to see the ICJ build the constitution of the UN, but it is arguably a logical result of the ICJ’s de facto interstate nature.

This article has compared the ICJ to some of the most active and influential ICs, explaining why the ICJ’s influence is relatively limited. The ICJ’s role is intentionally limited. States want the ICJ to primarily serve as an interstate dispute settlement body. Proposals to expand access to the ICJ’s advisory role have been repeatedly rebuffed. While the ICJ plays a limited role as an appellate jurisdiction in cases involving UN employees, both states and ICJ judges have not wanted to expand the ICJ’s adjudicatory role in the UN system. For example, the ICJ has not been given a role adjudicating international law violations by UN peacekeepers, nor has it been able to assess the UN’s liability in introducing cholera in Haiti.[84]

The largest impediment to the ICJ broadening its legal and political authority is its interstate nature. Many advocates wish that the ICJ could and would do more to build and enforce international law. Yet expanding the ICJ role through judicial means such as expansive legal interpretations could be counterproductive. Potential litigants understand that the only pathway to encourage state compliance with ICJ rulings is to appeal to the litigating governments, and this reality limits the attraction of bringing contentious and advisory cases to the ICJ. ICJ judges are also aware of these limitations, and they often refuse entreaties to issue legally expansive rulings. The ICJ’s influence can therefore be seen as being limited by design. The ICJ interstate dispute settlement role is important, and, for many issues and countries, the ICJ is the most high-profile international legal body able to fulfil this role. In this respect, and perhaps ironically, the value that UN members derive from having the ICJ as a limited interstate dispute settlement body could actually be undercut if the ICJ became an active constitutional interpreter in the UN system.

* Professor of Political Science and Law at Northwestern University and a permanent visiting professor at iCourts, the Danish National Research FoundationR[1]s Centre of Excellence, University of Copenhagen Faculty of Law. This article was presented at the workshop on National Encounters with the International Court of Justice at Melbourne Law School, University of Melbourne, Australia, on 20 May 2020 (via Zoom), hosted by Professor Hilary Charlesworth and Professor Margaret Young for their research project on The Potential and Limits of International Adjudication, funded by the Australian Research Council (DP180101318). Thanks to Margaret Young, Shirley Scott, Emma Nyhan, DC Peat, Ken Keith and participants of the National Encounters with the International Court of Justice workshop for their helpful comments on earlier drafts.

[1] Compliance constituencies include compliance partners (those actors with the power to choose compliance with the law) and compliance supporters (legal and political actors that enable and pressure courts and compliance partners): see Karen J Alter, The New Terrain of International Law: Courts, Politics, Rights (Princeton University Press, 2014) 53–4 (‘The New Terrain of International Law’).

[2] I am not making a claim of statistical significance, but the general definition of robust statistical significance is a 95% correlation, which, by definition, means that up to 5% of the cases are outliers. There are circumstances in which an exception does call a finding into question, but the mere fact of an exception does not falsify a claim. This difference in analytical expectations can lead political scientists and lawyers to speak past each other. Political scientists value clear arguments that require strong statements. Lawyers then counter with exceptions and nuances. Political scientists use terms such as ‘often’, ‘generally’, ‘ceteris paribus’, ‘in principle’ and ‘likely’ to indicate that a claim is probabilistic rather than absolute. For more on the different styles of lawyers and political scientists, see Karen J Alter, Renaud Dehousse and Georg Vanberg, ‘Law, Political Science and EU Legal Studies: An Interdisciplinary Project?’ (2002) 3(1) European Union Politics 113.

[3] While formally dissolved in 1946, the PCIJ issued its final ruling in 1940. Between 1922 and 1940, the PCIJ dealt with 29 contentious cases between states and delivered 27 advisory opinions. For more information, see ‘Permanent Court of International Justice’, International Court of Justice (Web Page) <https://www.icj-cij.org/en/pcij>, archived at <https://perma.cc/HHH6-2X44>.

[4] Inge van Hulle, ‘Imperial Consolidation through Arbitration: Territorial and Boundary Disputes in Africa (1870–1914)’ in Ignacio de la Rasilla and Jorge E Viñuales (eds), Experiments in International Adjudication: Historical Accounts (Cambridge University Press, 2019) 55; Jenny S Martinez, The Slave Trade and the Origins of International Human Rights Law (Oxford University Press, 2012).

[5] Alter, The New Terrain of International Law (n 1) 114–15.

[6] See Manley O Hudson, International Tribunals: Past and Future (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and Brookings Institution, 1944); Suzanne Katzenstein, ‘In the Shadow of Crisis: The Creation of International Courts in the Twentieth Century’ (2014) 55(1) Harvard International Law Journal 151.

[7] Constitution of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, opened for signature 16 November 1945, 4 UNTS 275 (entered into force 4 November 1946).

[8] Ibid art XIV; Seymour J Rubin, ‘The Judicial Review Problem in the International Trade Organization’ (1949) 63(1) Harvard Law Review 78, 85.

[9] Constitution of the World Health Organization, opened for signature 22 July 1946, 14 UNTS 185 (entered into force 7 April 1948) art 75; Rubin (n 8) 85.

[10] Treaty of Peace between the Allied and Associated Powers and Germany, signed 28 June 1919, 225 ConTS 188 (entered into force 10 January 1920) pt XIII (‘The Constitution of the International Labour Organisation’) arts 26, 29, 31; Rubin (n 8) 85.

[11] Havana Charter for an International Trade Organization, opened for signature 24 March 1948 (not in force) art 96.

[13] Whether the ICJ has jurisdiction is, sometimes, contested, and the ICJ has claimed jurisdiction even where there is no clear textual delegation. For example, the ICJ claimed jurisdiction based on an agreement among two parties to bring an unresolved matter to the Court: Maritime Delimitation and Territorial Questions between Qatar and Bahrain (Qatar v Bahrain) (Jurisdiction and Admissibility) [1994] ICJ Rep 112.

[14] This figure is noted in Cesare PR Romano, ‘The Shift from the Consensual to the Compulsory Paradigm in International Adjudication: Elements for a Theory of Consent’ (2007) 39(4) New York University Journal of International Law and Politics 791, 817 (‘The Shift from the Consensual to the Compulsory Paradigm in International Adjudication’). A recent visit to the ICJ’s website reports that the last treaty to designate the ICJ occurred in 2006, so we can presume that Romano’s figure remains mostly, if not fully, correct: see ‘Treaties’, International Court of Justice (Web Page) <https://www.icj-cij.org/en/treaties>, archived at <https://perma.cc/M6DB-HRK5>.

[15] See Dapo Akande, ‘The Competence of International Organizations and the Advisory Jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice’ (1998) 9(3) European Journal of International Law 437. The list of authorised UN actors and the advisory ruling requests that these actors have made is available here: ‘Organs and Agencies Authorized to Request Advisory Opinions’, International Court of Justice (Web Page) <https://www.icj-cij.org/en/organs-agencies-authorized>, archived at <https://perma.cc/BWQ5-Y8YV>.

[16] In the 1990s, the ICJ issued 11 rulings on the merits and three advisory opinions. Between 2000 and 2009, the ICJ issued 25 rulings on the merits and one advisory opinion. Between 2010 and 2019, the ICJ issued 17 rulings on the merits and three advisory opinions (yet, during this time, 31 cases were also initiated). These numbers are based on updated data from Alter, The New Terrain of International Law (n 1). See also ‘List of All Cases’, International Court of Justice (Web Page) <https://www.icj-cij.org/en/list-of-all-cases>, archived at <https://perma.cc/5H82-WZGR>.

[17] The New Terrain of International Law adopts a conservative counting strategy so that the evidence of over 37,000 international judicial rulings on the merits cannot be dismissed as an inflated number: see Alter, The New Terrain of International Law (n 1) 77–9. This strategy works less well for this Special Issue, which is interested in the overall encounters with the ICJ. For example, my focus on state demand for ICJ dispute resolution leads me to exclude cases seeking a reinterpretation of an earlier ICJ ruling. Yet the reappearance of an earlier case is an additional encounter.

[18] Note that a number of the advisory decisions pertain to the administrative operation of the UN.

[19] Scholars of European legal integration emphasise how the ECJ built its legal influence by following a strategy of incrementalism. TC Hartley explained the strategy as follows:

A common tactic is to introduce a new doctrine gradually: in the first case that comes before it, the Court will establish the doctrine as a general principle, but suggest that it is subject to various qualifications; the Court may even find some reason why it should not be applied to the particular facts of the case. The principle, however, is now established. If there are not too many protests, it will be re-affirmed in later cases; the qualifications can then be whittled away and the full extent of the doctrine revealed.

TC Hartley, The Foundations of European Community Law: An Introduction to the Constitutional and Administrative Law of the European Community (Oxford University Press, 6th ed, 2007) 76. See also Laurence R Helfer and Anne-Marie Slaughter, ‘Toward a Theory of Effective Supranational Adjudication’ (1997) 107(2) Yale Law Journal 273, 314; JHH Weiler, ‘The Transformation of Europe’ (1991) 100(8) Yale Law Journal 2403, 2447.

[20] Many scholars expect international judges to influence international law via dialogues with domestic interlocutors: see Anne-Marie Slaughter, ‘A Typology of Transjudicial Communication’ (1994) 29(1) University of Richmond Law Review 99; JHH Weiler, ‘A Quiet Revolution: The European Court of Justice and Its Interlocutors’ (1994) 26(4) Comparative Political Studies 510. Elsewhere, I explain how out-of-court interactions with domestic interlocutors can embolden and enhance the ability of international judges to develop international law: Karen J Alter, The European Court’s Political Power: Selected Essays (Oxford University Press, 2009) ch 4, updated and expanded in Karen J Alter and Laurence R Helfer, Transplanting International Courts: The Law and Politics of the Andean Tribunal of Justice (Oxford University Press, 2017).

[21] Cesare PR Romano, ‘The Proliferation of International Judicial Bodies: The Pieces of the Puzzle’ (1999) 31(4) New York University Journal of International Law and Politics 709. I explain why the end of the Cold War created a juncture contributing to the proliferation of ICs, and I document the transition to new-style ICs and the rise of litigation rates after the end of the Cold War. On critical junctures, see Karen J Alter, ‘The Evolving International Judiciary’ (2011) 7 Annual Review of Law and Social Science 387. On the transition to new-style ICs, see Alter, The New Terrain of International Law (n 1) 84.

[22] Eighteen of today’s 21 operational ICs are new-style ICs: Alter, The New Terrain of International Law (n 1) 84. The number of courts reported here is smaller because the International Criminal Tribunals for Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia and the Southern African Development Community Tribunal are no longer operational.

[23] These categories and their significance are further explained in ibid 81–3.

[24] Between 1990 and 2015, the ECJ issued 18,435 binding rulings, and the ECtHR issued 21,059 binding rulings.

[25] This claim is challenged in Aloysius P Llamzon, ‘Jurisdiction and Compliance in Recent Decisions of the International Court of Justice’ (2007) 18(5) European Journal of International Law 815.

[26] For a list of countries accepting the ICJ’s compulsory jurisdiction, see ‘Declarations Recognizing the Jurisdiction of the Court as Compulsory’, International Court of Justice (Web Page) <https://www.icj-cij.org/en/declarations>, archived at <https://perma.cc/P8B4-UJCY>.

[27] The WTO replaced the GATT in 1994; the 1990–94 data includes GATT panels. Appellate Body decisions are excluded to avoid double counting cases.

[28] The Inter-American Court of Human Rights system, with only 27 member states during most of this period, issued 301 binding decisions; the Andean Tribunal (‘ATJ’), with five member states for most of this period, issued 2,853 binding rulings; the Benelux court, with three member states, issued 98 rulings; the Community Court for the Organization for the Harmonization of Business Law in Africa (‘OHADA’), with 15 member states, issued 970 rulings in this period notwithstanding a civil war in the Ivory Coast, its institutional home; the Caribbean Court of Justice issued 123 decisions; and the 15 member court of the Economic Community of West African States issued 122 rulings.

[29] Hilary Charlesworth and Margaret A Young, ‘National Encounters with the International Court of Justice: Introduction to the Special Issue’ [2021] MelbJlIntLaw 1; (2021) 21(3) Melbourne Journal of International Law 502, 505.

[30] I co-authored an entire book about this Tribunal, but throughout, we discuss the Tribunal’s very limited substantive influence: see Alter and Helfer (n 20).

[31] Military and Paramilitary Activities in and against Nicaragua (Nicaragua v United States of America) (Merits) [1986] ICJ Rep 14 (‘Nicaragua’).

[32] See, eg, Paul Lewis, ‘World Court Supports Nicaragua after US Rejected Judges’ Role’, The New York Times (New York, 28 June 1986) 1.

[33] Anthea Roberts, Is International Law International? (Oxford University Press, 2017) 148–9. Roberts’ larger point is that national casebooks tend to focus on rulings involving their country.

[34] Paul S Reichler, ‘Holding America to Its Own Best Standards: Abe Chayes and Nicaragua in the World Court’ (2001) 42(1) Harvard International Law Journal 15.

[35] See, eg, Michael J Glennon, ‘Protecting the Court’s Institutional Interests: Why Not the Marbury Approach?’ (1987) 81(1) American Journal of International Law 121, 124; W Michael Reisman, ‘The Other Shoe Falls: The Future of Article 36(1) Jurisdiction in the Light of Nicaragua’ (1987) 81(1) American Journal of International Law 166; Anthony D’Amato, ‘Modifying US Acceptance of the Compulsory Jurisdiction of the World Court’ (1985) 79(2) American Journal of International Law 385.

[36] See, for example, John Norton Moore, who described the Nicaragua decision as ‘a tragedy for world order and for hopes to strengthen international adjudication’: John Norton Moore, ‘The Nicaragua Case and the Deterioration of World Order’ (1987) 81(1) American Journal of International Law 151, 152. Mark Weston Janis opined that the Nicaragua decision ‘display[s] the Court in its weakest and least effectual role’: Mark Weston Janis, ‘Somber Reflections on the Compulsory Jurisdiction of the International Court’ (1987) 81(1) American Journal of International Law 144, 146. Anthony D’Amato bemoaned that ‘[s]adly, the [Nicaragua] Judgment reveals that the judges have little idea about what they are doing’: Anthony D’Amato, ‘Trashing Customary International Law’ (1987) 81(1) American Journal of International Law 101, 102.

[37] The decision truly incensed Alfred Rubin and Robert Bork: see Alfred P Rubin and Robert Bork, ‘The Limits of “International Law”’ [1990] (Spring) National Interest 122; Robert H Bork, Coercing Virtue: The Worldwide Rule of Judges (American Enterprise Institute Press, 2003) 38–42. For an analysis of the influence of this movement, see Jens David Ohlin, The Assault on International Law (Oxford University Press, 2015) 217–22.

[38] Karen J Alter, ‘Agent or Trustee? International Courts in Their Political Context’ (2008) 14(1) European Journal of International Relations 33, 53.

[39] Nicaragua filed a letter requesting a discontinuance of the case on 12 September 1991. See ICJ order of 26 September 1991: Military and Paramilitary Activities in and against Nicaragua (Nicaragua v United States of America) (Order on 26 September 1991) [1991] ICJ Rep 47.

[41] Margaret A Young, Emma Nyhan and Hilary Charlesworth, ‘Studying Country-Specific Engagements with the International Court of Justice’ (2019) 10(4) Journal of International Dispute Settlement 582.

[42] Numerous scholars have decried using compliance as a measure of IC and international law effectiveness: see, eg, Lisa L Martin, ‘Against Compliance’ in Jeffrey L Dunoff and Mark A Pollack (eds), Interdisciplinary Perspectives on International Law and International Relations: The State of the Art (Cambridge University Press, 2013) 591; Robert Howse and Ruti Teitel, ‘Beyond Compliance: Rethinking Why International Law Really Matters’ (2010) 1(2) Global Policy 127; Jana von Stein, ‘The Engines of Compliance’ in Jeffrey L Dunoff and Mark A Pollack (eds), Interdisciplinary Perspectives on International Law and International Relations: The State of the Art (Cambridge University Press, 2013) 477. Some scholars discuss ‘partial compliance’ as a better measure: see, eg, Darren Hawkins and Wade Jacoby, ‘Partial Compliance: A Comparison of the European and Inter-American Court of Human Rights’ (2010) 6(1) Journal of International Law and International Relations 35.

[43] This argument was first raised by George W Downs, David M Rocke and Peter N Barsoom, ‘Is the Good News about Compliance Good News about Cooperation?’ (1996) 50(3) International Organization 379. Kal Raustiala explains that the correct metric is ‘effectiveness’, meaning a change in behaviour in a desirous direction: Kal Raustiala, ‘Compliance and Effectiveness in International Regulatory Cooperation’ (2000) 32(3) Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law 387.

[44] See Raustiala (n 43); Laurence R Helfer, ‘The Effectiveness of International Adjudicators’ in Cesare PR Romano, Karen J Alter and Yuval Shany (eds), The Oxford Handbook of International Adjudication (Oxford University Press, 2014) 464.

[45] Alec Stone Sweet and Thomas L Brunell, ‘Trustee Courts and the Judicialization of International Regimes’ [2013] (Spring) Journal of Law and Courts 61. My discussion of IC trustees merges the multilateral and transnational politics pathways: Alter, ‘Agent or Trustee? International Courts in Their Political Context’ (n 38).

[46] To learn more about these models, see Alter, The New Terrain of International Law (n 1) 42–52.

[47] Each model actually represents an entirely different conception of how the politics of international law works. I explain the models in more detail and combine them into the ‘altered politics’ framework: see ibid ch 2.

[48] Eric A Posner and John C Yoo, ‘Judicial Independence in International Tribunals’ (2005) 93(1) California Law Review 1. For a critique of this argument, see Laurence R Helfer and Anne-Marie Slaughter, ‘Why States Create International Tribunals: A Response to Professors Posner and Yoo’ (2005) 93(3) California Law Review 899.

[49] For a deeper discussion of the interstate arbiter role and its variants, see Alter, The New Terrain of International Law (n 1) 43–6.

[50] Romano, ‘The Shift from the Consensual to the Compulsory Paradigm in International Adjudication’ (n 14) 818.

[51] Martin Shapiro, Courts: A Comparative and Political Analysis (University of Chicago Press, 1981) 8–17.

[52] Charter of the United Nations art 94(2).

[53] Aloysius Llamzon argues that the UN Security Council’s role is limited because only ‘judgments’ are subject to Security Council enforcement, only parties to the dispute can request enforcement and the Security Council has discretion in deciding whether to act: Aloysius P Llamzon, ‘Jurisdiction and Compliance in Recent Decisions of the International Court of Justice’ (2007) 18(5) European Journal of International Law 815, 821–2. See also Attila Tanzi, ‘Problems of Enforcement of Decisions of the International Court of Justice and the Law of the United Nations’ (1995) 6(4) European Journal of International Law 539. These legal insights may be correct, but it is interesting to note that a recent document issued by the UN presented a rather different perspective. A summary of the report concluded that the Security Council’s refusal to resort to the ICJ or press countries to do so is

part of a larger Council dynamic: the Council has been reluctant to resort to other UN organs and external actors that it does not control and whose actions it cannot necessarily predict. Instead, the Council has opted to retain control and decision-making powers at the possible expense of effectiveness while not taking full advantage of its options. From the perspective of the P5, when it comes to the Court more specifically, the Court’s jurisprudence has, at times, been perceived as hostile to their interests.

Security Council Report, ‘In Hindsight: The Security Council and the International Court of Justice’ (January 2017) Monthly Forecast 1, 2.

[54] American actors have used ICJ litigation to try to influence US debates. The Nicaragua case involved a US professor — Abram Chayes — spearheading Nicaragua’s legal case: see Reichler (n 34). The Avena case, seeking a remedy for the US’s violation of the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations in cases involving 54 Mexican death row inmates, proceeded with the support of US death penalty opponents: Avena and Other Mexican Nationals (Mexico v United States of America) (Judgment) [2004] ICJ Rep 12 (‘Avena’).

[55] I discuss this issue in Karen J Alter, ‘National Perspectives on International Constitutional Review: Diverging Optics’ in Erin F Delaney and Rosalind Dixon (eds), Comparative Judicial Review (Edward Elgar, 2018) 244.

[57] The LaGrand case, raised by Germany to challenge the US’s death penalty policies, might be an example of a state raising a case to develop international law: LaGrand (Germany v United States of America) (Judgment) [2001] ICJ Rep 466.

[58] The next three paragraphs draw directly from Karen J Alter, Laurence R Helfer and Mikael Rask Madsen, ‘International Court Authority in a Complex World’ in Karen J Alter, Laurence R Helfer and Mikael Rask Madsen (eds), International Court Authority (Oxford University Press, 2018) 3. Karen J Alter, Laurence R Helfer and Mikael Rask Madsen, ‘How Context Shapes the Authority of International Courts’ in Karen J Alter, Laurence R Helfer and Mikael Rask Madsen (eds), International Court Authority (Oxford University Press, 2018) 24 explains these categories in more detail.

[59] Alter, Helfer and Madsen, ‘How Context Shapes the Authority of International Courts’ (n 58) 28.

[60] Alter, Helfer and Madsen, ‘International Court Authority in a Complex World’ (n 58) 3–4.

[61] Alter, Helfer and Madsen, ‘How Context Shapes the Authority of International Courts’ (n 58) 31–3.

[62] Ibid 24.

[63] Ibid 34.

[64] Ibid 36.

[65] Alter, Helfer and Madsen, ‘International Court Authority in a Complex World’ (n 58) 13–14.

[66] Ibid 13.

[67] Ibid 14.

[68] Alter, Helfer and Madsen, ‘How Context Shapes the Authority of International Courts’ (n 58) 36.

[69] Statute of the International Court of Justice art 59.

[70] See generally Akande (n 15).

[71] See, eg, Mark Angehr, ‘The International Court of Justice’s Advisory Jurisdiction and the Review of Security Council and General Assembly Resolutions’ (2009) 103(2) Northwestern University Law Review 1007; Akande (n 15); Amelia Keene, ‘The Forgotten Potential of the Advisory Jurisdictions of International Courts and Tribunals as a Check on the Actions of International Organisations’ (2016) 14(1) New Zealand Journal of Public and International Law 67; Stephen M Schwebel, ‘Widening the Advisory Jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice without Amending Its Statute’ (1984) 33(2) Catholic University Law Review 355; David Sloss, ‘Using International Court of Justice Advisory Opinions to Adjudicate Secessionist Claims’ (2002) 42(2) Santa Clara Law Review 357.

[72] Schwebel (n 71); Louis B Sohn, ‘Broadening the Advisory Jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice’ (1983) 77(1) American Journal of International Law 124. In 1982, the US House of Representatives unanimously urged the US President to pursue a ‘preliminary opinion’ jurisdiction for the ICJ: see Stephen R Crilly, ‘Recent Developments: A Nascent Proposal for Expanding the Advisory Opinion Jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice’ (1983) 10(1) Syracuse Journal of International Law and Commerce 215; Louis B Sohn, ‘Judge Dillard and the Expansion of the Advisory Jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice’ (1983) 23(3) Virginia Journal of International Law 383.

[73] Sean D Murphy, ‘Self-Defense and the Israeli Wall Advisory Opinion: An Ipse Dixit from the ICJ?’ (2005) 99(1) American Journal of International Law 62.

[74] Akande (n 15); Christopher Greenwood, ‘Judicial Integrity and the Advisory Jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice’ in Giorgio Gaja and Jenny Grote Stoutenburg (eds), Enhancing the Rule of Law through the International Court of Justice (Brill Nijoff, 2014) 63; Mahasen M Aljaghoub, The Advisory Function of the International Court of Justice 1946–2005 (Springer, 2006) ch 4.

[76] See Gregory C Shaffer, Defending Interests: Public–Private Partnerships in WTO Litigation (Brookings Institution Press, 2003); Gregory Shaffer, James Nedumpara and Aseema Sinha, ‘State Transformation and the Role of Lawyers: The WTO, India, and Transnational Legal Ordering’ (2015) 49(3) Law and Society Review 595.

[77] Emilia Justyna Powell, Islamic Law and International Law: Peaceful Resolution of Disputes (Oxford University Press, 2020); Emilia Justyna Powell, ‘Islamic Law States and the International Court of Justice’ (2013) 50(2) Journal of Peace Research 203.

[78] On the requirements for an international judicial system, see Jenny S Martinez, ‘Towards an International Judicial System’ (2003) 56(2) Stanford Law Review 429.

[79] Alter, The New Terrain of International Law (n 1) 10–17.

[80] On the dispute resolution role, see ibid ch 5 pt 1. On the administrative review role, see at ch 6 pt 1. On the enforcement court role, see at ch 7 pt 1. On the constitutional court role, see at ch 8 pt 1, especially at 285–90.

[81] Alter and Helfer (n 20) 281–3.

[82] Statute of the International Court of Justice arts 36, 38.

[83] This information is drawn from Alter, The New Terrain of International Law (n 1) 101.

[84] See Mara Pillinger, Ian Hurd and Michael N Barnett, ‘How to Get Away with Cholera: The UN, Haiti, and International Law’ (2016) 14(1) Perspectives on Politics 70.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/MelbJlIntLaw/2021/9.html