Sydney Law Review

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Sydney Law Review |

|

Banning Orders: An Empirical Analysis of the Dominant Mode of Corporate Law Enforcement

in Australia

Jasper Hedges,[∗] George Gilligan[†] and Ian Ramsay[‡]

Abstract

This article is the first detailed empirical study of banning orders made under legislation administered by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (‘ASIC’). This method of enforcement of corporate law has been little researched, yet it is arguably the dominant mode of corporate law enforcement in Australia. The article examines the prevalence of banning orders relative to other major enforcement outcomes and analyses the number and duration of bans prohibiting individuals from managing corporations, providing financial services, engaging in credit activities, and auditing self-managed super funds. The dataset — encompassing 2777 banning orders across a 29-year period — reveals a significant upward trend in banning orders and a corresponding downward trend in most other major enforcement outcomes. In the 10 years since 2005–06, there were more banning orders than all other major enforcement outcomes combined. Banning orders were also increasingly severe in duration, due to an upward trend in financial services and credit activity bans, about 47% of which were permanent in duration collectively. The increasing prevalence and severity of banning orders, an estimated 87% of which were administrative decisions by ASIC, or appeals from such decisions (rather than first instance decisions by the courts), raise concerns regarding the accountability of banning practices. The judiciary has acknowledged that banning orders, while primarily protective in purpose, also function as a form of retribution akin to criminal punishment. Yet administrative hearings are not subject to the rules of evidence that apply to criminal court proceedings and the reasons for banning orders are not available to the public. The increasingly heavy use of these effectively punitive orders demands a higher standard of public accountability. Improved access to administrative banning decisions would advance ASIC’s stated commitment to transparency, open data and accountability, and give effect to the Australian Government’s Public Data Policy Statement and innovation agenda.

There is considerable interest by academics, politicians and regulators in the enforcement of corporate law and an increasing number of empirical studies of how such enforcement is undertaken.[1] Yet little of this research has focused on the use of orders that ban individuals from undertaking certain activities — whether managing companies or offering financial services. This article presents the findings of the first detailed empirical study on the use of banning orders to enforce legislation administered by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (‘ASIC’), which is the statutory agency responsible for regulating corporate governance, financial services and market integrity. The findings reveal a significant upward trend in the use of banning orders and a corresponding downward trend in the use of most other major enforcement outcomes from 1997–98 to 2014–15. Banning orders are arguably the dominant mode of corporate law enforcement in Australia. However, despite the increasing prevalence of banning orders, they have received little academic attention[2] relative to other major enforcement outcomes, such as criminal prosecutions by the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions (‘CDPP’)[3] and civil proceedings brought by ASIC.[4]

Likewise, banning orders have received little academic attention relative to enforceable undertakings[5] and infringement notices.[6]

This article sheds much-needed light on the use of banning orders to enforce legislation administered by ASIC. The purpose of the article is two-fold. First,

it seeks to examine the prevalence of banning orders relative to other major enforcement mechanisms via an empirical analysis of the number of banning orders and other enforcement outcomes from 1997–98 to 2014–15.[7] The data reveals that more varied use of enforcement mechanisms in the late 1990s and early 2000s has given way to an increasingly dominant use of banning orders relative to other major enforcement outcomes. In particular, there has been a sustained period of frequent use of banning orders over the last ten years (2005–06 to 2014–15), with more banning orders made during this period than all other major enforcement outcomes combined.[8] These findings may partly reflect ASIC’s increasing mandate and budgetary pressures[9] and a need for quicker, cheaper enforcement alternatives. ASIC’s Annual Report 2014–2015 indicates that administrative enforcement actions, which account for the vast majority of banning orders (an estimated 87% of banning orders are administrative),[10] are quicker and less expensive than criminal and civil actions.[11]

The second purpose of this article is to identify trends in relation to the use of particular types of banning orders via a detailed empirical analysis of the number and duration of bans in relation to: managing corporations (‘company bans’), providing financial services (‘financial bans’), engaging in credit activities (‘credit bans’), and being an approved self-managed super fund auditor (‘SMSF bans’).[12] The dataset on banning orders was sourced directly from ASIC and contains 1992 company bans (1987 to 2015), 660 financial bans (1992 to 2015), 91 credit bans (2001 to 2015) and 34 SMSF bans (2010 to 2015).[13] One of the key findings of this analysis is that, while company bans are the most frequently imposed bans in aggregate terms, there is an upward trend in the number of financial and credit bans.[14] Another key finding is that financial, credit and SMSF bans tend to have a significantly greater duration than company bans. Forty-five percent of financial bans, 59% of credit bans and 100% of SMSF bans were permanent, as compared with 1% of company bans.[15] This finding is partially a reflection of the fiveyear time limit on administrative company bans[16] along with the high proportion of administrative banning orders.

The increasing prevalence and severity of banning orders, which are mostly administrative decisions by ASIC, raise significant concerns about the accountability of ASIC’s use of banning powers. The judiciary has acknowledged that banning orders, while primarily protective in purpose, also function as a form of retribution akin to criminal punishment.[17] Yet administrative hearings are not constrained by the rules of evidence and procedure that apply to criminal court proceedings[18] and the public cannot readily access information on the facts and reasons that form the basis for administrative banning orders.[19] The increasingly heavy use of these effectively punitive orders demands a higher standard of public accountability. It is argued that improved access to administrative banning decisions would advance ASIC’s stated commitment to transparency, open data and accountability[20] and give effect to the Australian Government’s Public Data Policy Statement and innovation agenda.[21]

The structure of this article is as follows. Part II provides a brief introduction to ASIC’s regulatory responsibilities and enforcement powers, followed by an explanation of how the term ‘banning orders’ is defined in this article and the legislative provisions under which such orders are made. Part IIIA presents the empirical findings on the frequency of banning orders compared with other major enforcement outcomes. Parts IIIB and IIIC present the results of the detailed empirical analysis of the number and duration of company, financial, credit and SMSF bans. Part IV discusses the accountability implications of the increasing prevalence and severity of banning orders. The empirical findings show that banning orders constitute an increasingly dominant form of corporate law enforcement in Australia which, thus far, has been the subject of little academic attention and insufficient public accountability.

ASIC is a publicly funded independent statutory agency established under the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 1989 (Cth) (now repealed) and continuing in existence under s 261 of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (‘ASIC Act’). It administers a broad range of legislation relating to corporate governance, financial services and market integrity.[22] ASIC’s approach to regulation is guided by three strategic priorities: promoting investor and consumer trust and confidence; ensuring fair and efficient markets; and providing efficient registration services.[23] Most of ASIC’s regulatory resources (approximately 70%) are devoted to surveillance and enforcement of the laws that it administers. In ASIC’s own words, it is a ‘law enforcement agency’[24] that ‘use[s] enforcement to deter misconduct’.[25] ASIC’s enforcement activities are outlined in half-yearly enforcement reports that contain case studies and statistics on criminal, civil, administrative and negotiated enforcement outcomes in relation to various types of misconduct.[26]

ASIC’s total operating expenditure in 2016–17 was $392 million and it received approximately $342 million in appropriation revenue from the Federal Government.[27] The fact that ASIC commits most of its substantial regulatory resources to coercive law enforcement activity — of which banning orders form a significant, arguably dominant, component — highlights the importance of ensuring that its enforcement activity is subjected to sufficient accountability. While ASIC’s use of banning orders is legally accountable, in the sense that ASIC’s decisions can be appealed to the Administrative Appeals Tribunal for external merits review and are subject to judicial review, it is widely accepted that ASIC, as a publicly funded statutory agency, ought also to be accountable and transparent in the broader sense of being answerable to the public.[28] These issues are discussed further in Part IV in light of the empirical evidence presented in Part III, which shows an increasingly heavy reliance on administrative banning orders.

The empirical analysis of banning orders in this article is an analysis of the enforcement outcomes recorded in ASIC’s ‘Banned and Disqualified Register’ (‘Bans Register’), which list individuals who have been banned or disqualified from 1986 onward.[29] A copy of the Bans Register was requested from ASIC by the authors on 28 April 2016 and received on 4 May 2016.[30] The Bans Register contains the following information in relation to banning orders: name; address; category of ban; commencement date of ban; and cessation date of ban (in the case of non-permanent bans). The Register is divided into six categories of bans: (1) ‘Banned Securities’; (2) ‘Banned Futures’; (3) ‘Disqualified Director’; (4) ‘Disqualified SMSF’; (5) ‘AFS [Australian Financial Services] Banned & Disqualified’; and (6) ‘Credit Banned & Disqualified’.[31] Categories one and two, ‘Banned Securities’ and ‘Banned Futures’, refer to banning orders that were predecessors to the current financial services banning orders,[32] therefore categories one, two and five are referred to as ‘financial bans’ in this article. Categories three, four and six are referred to as ‘company bans’, ‘SMSF bans’ and ‘credit bans’ respectively. Part IIB explains the legislative provisions under which the specific banning orders within each of these four categories were made during the study period.

For the purposes of this article, the term ‘banning order’ is therefore defined as those enforcement outcomes that are contained in the Bans Register, consistent with ASIC’s definition of what constitutes a ‘banning’ or ‘disqualification’ order against an individual. The reason that some of the outcomes in the Register are referred to as ‘banning’ outcomes and others as ‘disqualification’ outcomes is simply that some of the legislative provisions use the term ‘banning’,[33] while others use the term ‘disqualification’.[34] There does not appear to be any substantive distinction between these terms. The distinction does not represent the distinction between administrative and judicial powers, as administrative powers are sometimes referred to as ‘banning’ powers[35] and other times as ‘disqualification’ powers.[36]

The empirical analysis of banning orders in this article does not cover any enforcement outcomes other than those contained in the Bans Register. There are many other types of enforcement outcomes that have a similar effect to the outcomes contained in the Bans Register (that is, a prohibitive injunctive effect). For example, ASIC may take action to suspend or cancel AFS licences,[37] credit licences[38] and the registration of auditors and liquidators.[39] Organisations (rather than individuals) can also be ‘banned’ or ‘disqualified’.[40] Enforceable undertakings often involve undertakings to cease allegedly unlawful conduct, apply to cancel registrations, and refrain from providing services or managing corporations.[41] Convictions for many criminal offences result in a fiveyear period of automatic disqualification from managing corporations.[42] For the most part, these other types of prohibitive injunctive enforcement outcomes are not included in the Bans Register, although enforceable undertakings and automatic disqualification periods very occasionally appear in the Register.

The Bans Register does not contain any information on the alleged misconduct, the reasoning, or the legislative provisions that formed the basis for the banning orders.[43] To determine the legislative provisions under which the bans listed in the Register were made, it was therefore necessary to draw upon other sources of data. For credit bans and SMSF bans, the certified banning documents were available free-of-charge via ASIC’s online ‘Banned & Disqualified’ search function,[44] with the exception of all but one of the credit bans made under state or territory legislation.[45] It was necessary to rely on ASIC’s media releases[46] to attempt to determine the legislative provisions under which most of the state or territory credit bans were made.

For company and financial bans, ASIC charges a $38.00 fee to access the certified banning documents,[47] so again it was necessary to rely on media releases to attempt to identify the relevant legislative provisions.[48] ASIC’s media releases were variable in their coverage of banning orders and only available from 2001 onward — thus, the following account of the legislative provisions under which the bans listed in the Bans Register were made is inclusive rather than exhaustive.

The ‘company bans’ listed in the Bans Register included: administrative disqualification orders by ASIC under s 206F of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (‘Corporations Act’), or appeals from such orders; judicial disqualification orders under ss 206C, 206D and 206E or predecessors to these provisions; occasional settlements during the course of judicial proceedings and matters resolved by consent orders; and occasional automatic disqualification periods under s 206B. However, ASIC’s media releases indicate that the bulk of company bans were administrative orders by ASIC under s 206F, or appeals from such orders. Every company ban contained in the Bans Register from 1 January 2001 to 31 December 2015 was searched in ASIC’s media release database. Of the 801 company bans contained in the Bans Register during this 15-year period, there was a media release covering 398 of the bans (49.69% media release coverage). Of the 398 company bans reported in ASIC’s media releases, 290 appeared to be administrative banning orders by ASIC under s 206F, or appeals from such orders (72.86% administrative bans).

The ‘financial bans’ listed in the Bans Register included: administrative banning orders by ASIC under s 920A of the Corporations Act, or appeals from such orders; occasional judicial restraining orders under s 1101B; occasional judicial injunctions under s 1324; occasional settlements during the course of judicial proceedings; and occasional enforceable undertakings involving voluntary bans under s 93AA of the ASIC Act. Again, the bulk of financial bans were administrative banning orders by ASIC under s 920A. Every financial ban from 1 January 2001 to 31 December 2015 was searched in ASIC’s media release database. There was a media release for all but 37 of the 484 financial bans since 1 January 2001 (92.36% media release coverage). Of the 447 financial bans reported in ASIC’s media releases, all but 15 appeared to be administrative banning orders by ASIC under s 920A, or appeals from such orders (96.64% administrative bans).

The ‘credit bans’ listed in the Bans Register were: administrative banning orders by ASIC under s 80 of the National Consumer Credit Protection Act 2009 (Cth) (‘Credit Act’), or appeals from such orders; and banning orders under a law of a state or territory.[49] With regard to the latter category of banning orders, it was only possible to determine the empowering legislation in two cases. One was a ban under ss 82 and 83 of the Finance Brokers Control Act 1975 (WA)[50] and the other was a ban under s 23 of the Consumer Credit (Queensland) Act 1994 (Qld).[51] Only 3 of the 20 (15%) state or territory credit bans were covered in ASIC’s media releases, while 68 of the 71 (95.77%) bans made under s 80 of the Credit Act were covered in media releases. In addition to the 71 administrative banning orders made by ASIC under s 80, at least 4 of the 20 banning orders made under a law of a state or territory appeared to be administrative decisions, meaning that a total of 75 out of 91 credit bans were administrative (82.42%).

The ‘SMSF bans’ listed in the Bans Register were: administrative banning orders by the Australian Taxation Office (‘ATO’) under s 131 of the Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act 1993 (Cth) (‘SIS Act’); and administrative banning orders by ASIC under s 130F of the SIS Act. There was also one ban by the ATO under s 126A(2) of the SIS Act, prohibiting the person from being a trustee — or a responsible officer of a body corporate that is a trustee, investment manager or custodian — of a superannuation entity. Up until 31 January 2013, SMSF bans were carried out exclusively by the ATO under s 131 of the SIS Act. ASIC acquired the power to make SMSF bans on 31 January 2013[52] and the ATO and ASIC are now co-regulators of SMSF auditors.[53] None of the banning orders made by the ATO were covered in ATO[54] or ASIC media releases, while 4 out of the 6 bans by ASIC were covered in ASIC’s media releases (66.67% media release coverage). There were 28 banning orders made by the ATO from 2010 to 2012 and 6 banning orders made by ASIC in 2014 to 2015 (100% administrative bans).

In total, 954 of the 1410 banning orders listed in the Bans Register during the period 1 January 2001 to 31 December 2015 were reported in ASIC’s media releases and/or available free-of-charge via ASIC’s ‘Banned & Disqualified’ search function[55] (67.66% reporting coverage). Of the 954 reported bans, 831 of them were administrative decisions, or appeals from such decisions (87.11% administrative bans). In other words, this suggests that about 87% of all banning orders are administrative decisions (or appeals from such decisions) and about 68% of banning orders are reported in ASIC’s media releases or available free-of-charge via ASIC’s ‘Banned & Disqualified’ search function.[56] The rate of reporting would be significantly higher were it not for the fact that only about 50% of company bans — the largest category of bans — are covered in media releases and such bans are not available free-of-charge via ASIC’s website. ASIC’s media release coverage of company bans declined steeply from 2007 onward and since 2011 only a small number of such bans have been covered in media releases each year.

This part of the article presents the empirical findings of the study on the frequency of banning orders relative to other major enforcement mechanisms, and the number and duration of company, financial, credit and SMSF bans.

This section presents a comparative analysis of the frequency of banning orders and other ‘major enforcement outcomes’ over the 18-year period from 1997–98 to

2014–15. For the purposes of this article, the term ‘major enforcement outcomes’ refers to criminal prosecutions by the CDPP, civil proceedings by ASIC, enforceable undertakings accepted by ASIC and infringement notices issued by ASIC. More minor enforcement outcomes have not been included in the study, such as public warning notices issued by ASIC under s 12GLC of the ASIC Act[57] and summary prosecutions by ASIC for ‘minor regulatory offences’.[58] Public warning notices are rarely issued by ASIC; it appears that a total of 10 such notices have been issued.[59] Summary prosecutions are very frequent,[60] but usually only result in a small fine for offences related to failure to assist liquidators under ss 475 and 530A of the Corporations Act.[61] This study also excludes administrative enforcement actions taken by ASIC relating to licence and registration variations, suspensions and cancellations.[62] While licensing-related actions can result in significant enforcement outcomes, there does not appear to be any database, register or resource available from which it is possible to determine the total number of such outcomes with any degree of certainty.[63]

The following methods were used to collect and classify data on each of the major enforcement outcomes that form part of this empirical study. As discussed in Part IIA, data on banning orders was requested from ASIC and provided in the form of the Bans Register. Data on criminal proceedings and civil proceedings was collected both directly from ASIC and from ASIC’s annual reports. In relation to the three final years of the comparative analysis period (1 July 2012 to 30 June 2015), detailed data was provided by ASIC that substantiates the data presented in ASIC’s enforcement reports during that period.[64] Regarding the first 15 years of the comparative analysis period (1 July 1997 to 30 June 2012) data on criminal and civil proceedings was collected from ASIC’s annual reports.[65] Data on enforceable undertakings was collected from ASIC’s enforceable undertakings register.[66] Data on infringement notices was collected from ASIC’s ‘Credit and ASIC Act infringement notices’ register,[67] ASIC’s ‘MDP Outcomes Register’,[68] and ASIC’s media releases,[69] as ASIC does not maintain a register of infringement notices issued for alleged contraventions of continuous disclosure provisions of the Corporations Act.

The data on banning orders, infringement notices and enforceable undertakings has been classified by reference to enforcement outcomes, rather than defendants. In some instances, the number of enforcement outcomes corresponded with the number of defendants, but in other cases it was either higher or lower than the number of defendants. A single defendant often received two or three types of banning orders; for example, a company ban, a financial ban and a credit ban. Similarly, in a number of instances a single corporate defendant received multiple infringement notices — ranging from two notices up to 35 notices — in relation to a group of related allegedly unlawful actions. Thus, in relation to banning orders and infringement notices, the total number of enforcement outcomes was higher than the number of defendants subject to such enforcement outcomes. Conversely, a single enforceable undertaking often applied to multiple defendants, so the total number of enforcement outcomes was lower than the number of defendants in relation to enforceable undertakings.

Data on criminal and civil outcomes has generally been classified as per ASIC’s classification in the substantiated enforcement report data and its annual reports.[70] It seems that the enforcement outcomes recorded in ASIC’s enforcement reports are by reference to defendants, rather than outcomes. ASIC’s enforcement report for January to June 2015 notes that the enforcement outcomes recorded in the report are ‘presented per defendant’.[71] It is not clear whether the civil and criminal outcomes recorded in ASIC’s annual reports are calculated on a per-outcome or perdefendant basis, as the reports do not explain how the data is classified and the classification system varies over time. Civil outcomes are described variously as civil enforcement actions completed,[72] civil proceedings taken,[73] and civil proceedings completed,[74] while criminal outcomes are described as criminal litigation completed,[75] people convicted,[76] and criminal proceedings completed.[77] Another limitation of ASIC’s annual report data is that, prior to 2011–12, it does not consistently differentiate between successful and unsuccessful outcomes. Most of the data categories, with the exception of ‘people convicted’, appear to include both successful and unsuccessful outcomes. However, the annual reports do not consistently provide separate civil and criminal success rates from which it is possible to determine the breakdown of successful and unsuccessful outcomes. This means that — unlike the data presented in this article on banning orders, enforceable undertakings and infringement notices — the data on civil and criminal outcomes includes some unsuccessful outcomes. However, the proportion of unsuccessful outcomes would be relatively small, as the average overall litigation success rate during the relevant period was 90.33%.[78] Given the lack of precision with which the data on criminal and civil outcomes is classified in ASIC’s annual reports, there is necessarily an element of approximation in relation to the number of civil and criminal outcomes contained in the dataset. Nevertheless, ASIC’s annual reports were the best available source of data on civil and criminal outcomes during the 18year comparative analysis period[79] and an effort was made to use the most consistent classification system possible.[80]

1 Total Number of Enforcement Outcomes

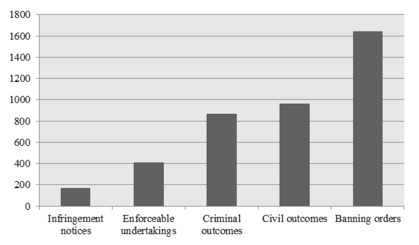

Figure 1 (below) presents the total number of each enforcement outcome during the 18-year period from 1997–98 to 2014–15. It shows that banning orders have been used significantly more frequently than other major enforcement mechanisms to enforce legislation administered by ASIC. Banning orders constituted 40.68% of all enforcement outcomes during the comparative analysis period (1641 of 4034). Despite receiving relatively little attention from academics in comparison to each of these other forms of enforcement outcome,[81] it is arguable that banning orders are the dominant mode of corporate law enforcement in Australia. While there are limitations to a comparative analysis based on the frequency of enforcement outcomes, without also comparing the magnitude and impact of such outcomes, banning orders are typically regarded as among the more severe forms of enforcement outcomes, as they involve incapacitation,[82] rather than monetary penalties or less severe injunctive outcomes such as good behaviour bonds and community service orders. The data in Part IIIC shows that banning orders are increasingly of a permanent duration, on account of the upward trend in the use of financial and credit bans and the high proportion of such bans that are permanent.

In interpreting Figure 1, it is important to note that not all of the enforcement mechanisms have been available since the beginning of the comparative analysis period. Banning orders (company bans and financial bans), criminal actions and civil actions were all available prior to 1 July 1997, whereas enforceable undertakings first became available on 1 July 1998[83] and infringement notices (for alleged breaches of continuous disclosure laws) first became available on 1 July 2004.[84] In terms of the average number of enforcement outcomes per year during the time that each form of action was available, there were 91 banning orders, 53 civil outcomes, 48 criminal outcomes, 24 enforceable undertakings and 15 infringement notices per year.

Figure 1: Number of enforcement outcomes from 1997–98 to 2014–15

2 Number of Enforcement Outcomes Per Year

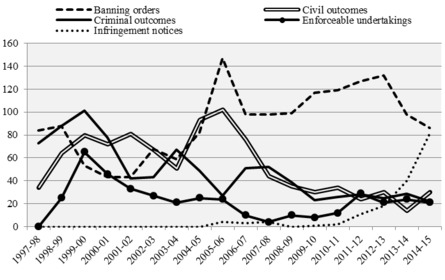

Figure 2 (below) presents the number of each enforcement outcome per year during the 18-year period from 1997–98 to 2014–15. The date of each enforcement outcome was determined by reference to the following: banning orders (date the ban commenced); civil and criminal outcomes (date of the enforcement reports and annual reports in which the outcomes were recorded); enforceable undertakings (date the undertaking was accepted); and infringement notices (date of the media release or entry in the infringement notices register).

Figure 2 shows that more varied enforcement outcomes in the late 1990s and early 2000s has given way to an increasingly dominant use of banning orders relative to other major enforcement outcomes. There was a significant upward trend in the use of banning orders over time, with a coefficient of +3.468524, indicating that the number of banning orders increased at approximately 3.5 bans per year. By contrast, there was a significant downward trend in the number of civil outcomes (coefficient of –3.024768) and criminal outcomes (coefficient of –3.810114) and a moderate downward trend in the number of enforceable undertakings (coefficient of

–1.563725).[85] While there has been an apparently sharp upward trend in the number of infringement notices since 1 July 2010, there is a question about whether the slope of this trend (coefficient of +6.400000) is representative of any sustained pattern in the use of infringement notices. There was one outlier matter involving 35 infringement notices issued to BMW Finance Australia Ltd for allegedly unlawful practices under the Credit Act relating to the repossession of motor vehicles, which constitutes almost half of all of the notices issued during 2014–15.[86] Prior to this matter, five infringement notices was the highest number of notices issued in relation to a single matter.[87]

In particular, there has been a sustained period of frequent use of banning orders over the last ten years (2005–06 to 2014–15), with more banning orders made during this period (n = 1121) than all other major enforcement outcomes combined (n = 1068). Figure 2 shows a distinct gap opening up between banning orders and other enforcement outcomes as of 2005–06. Thus, the comparative empirical analysis reveals that banning orders dominate other forms of enforcement outcome not only in terms of the total number of outcomes, but also in terms of the trends in the number of outcomes over time. While the data contains a number of significant fluctuations, making it difficult to predict whether this gap will widen or narrow over time,

it appears likely that banning orders will continue to be used more frequently than other enforcement actions in the near future. A possible exception to this prediction is that the frequency of infringement notices may overtake that of banning orders if the practice of issuing a large number of notices in relation to a single matter continues.

Figure 2: Number of enforcement outcomes per year from 1997–98 to 2014–15

Banning orders and infringement notices, the only major enforcement outcomes to display an upward trend, share an important characteristic, which is that they are the only actions that can be taken by ASIC unilaterally. Enforceable undertakings, although an administrative form of action, depend on the agreement of the parties subject to the undertaking, while criminal and civil sanctions are imposed by the judiciary. The upward trend in unilateral administrative action by ASIC may partly be a reflection of ASIC’s increasing responsibilities and budgetary pressures and the reportedly cheaper and quicker nature of administrative action.[88] Such action may provide a relatively straightforward avenue by which ASIC can achieve a greater level not only of frequency, but also impact of enforcement.

As discussed in Part IIIC, banning orders are increasingly severe in their duration and it is not uncommon for infringement notices to run into the hundreds of thousands of dollars.[89]

Given the increasing prevalence of banning orders relative to other major enforcement outcomes, it is important to have a clear understanding of how banning powers are used. This section provides a more detailed empirical analysis of the frequency of banning orders, including the total number of each type of ban, along with the total, average and median number of each type of ban per calendar year.

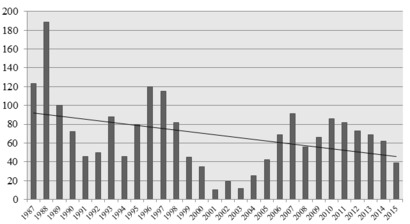

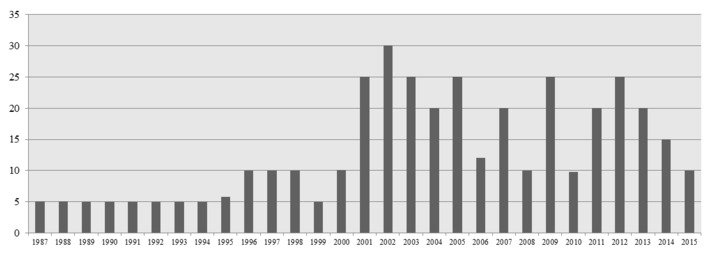

There were 1992 bans from managing companies (‘company bans’) during the 29year period from 1 January 1987 to 31 December 2015. The average number of company bans per calendar year was 68.69, while the median number per calendar year was 69. Figure 3 (below) shows the number of company bans per calendar year from 1987 to 2015.

The trend line in Figure 3 indicates that there has been a downward trend in the number of company bans over time. The coefficient is –1.647291, indicating that the number of company bans has decreased at approximately 1.6 per year. However, there are significant fluctuations in the data, so this trend is not a reliable basis upon which to make predictions about the future use of company bans. It is unclear why there is a notable decline in the number of company bans from 1998 to 2001. This may reflect a switch in focus away from company bans and towards financial bans in the lead up to the comprehensive reform of financial services laws that began with the Financial Services Reform Act 2001 (Cth).[90] In each of 1999, 2000 and 2001, there were less company bans than in any year prior to 1999 and more financial bans than in any year prior to 1999 (see Figure 4 below). However, this inverse correlation is not sufficiently strong to infer such a switch in focus with any certainty.

Figure 3: Number of company bans per calendar year from 1987 to 2015

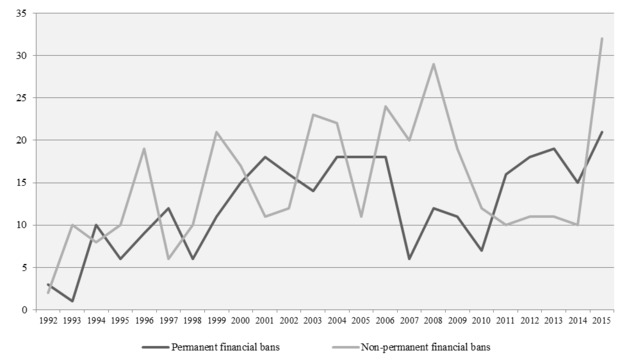

There were 660 bans from providing financial services (‘financial bans’) during the 24-year period from 1 January 1992 to 31 December 2015. The average number of financial bans per calendar year was 27.5, while the median number per calendar year was 28.5. Figure 4 (below) shows the number of financial bans per calendar year from 1992 to 2015.

The trend line in Figure 4 indicates that there has been an upward trend in the number of financial bans over time. The coefficient is +.910435, indicating that the number of financial bans has increased by approximately 0.9 bans per year. However, the fluctuations in the data, with a significant spike in 2015, again make it an unreliable basis upon which to make predictions as to the future use of financial bans.

Figure 4: Number of financial bans per calendar year from 1992 to 2015

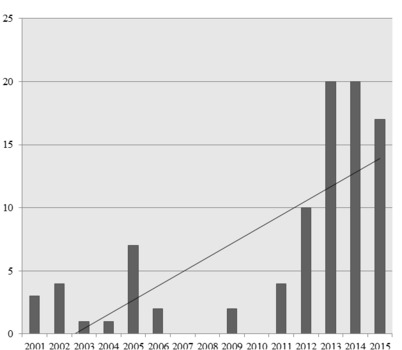

There were 91 bans from engaging in credit activities (‘credit bans’) during the 15year period from 1 January 2001 to 31 December 2015. The average number of credit bans per calendar year was 6.07, while the median number per calendar year was 3. The difference between the average and median is due to the increase in the frequency of credit bans after ASIC obtained its credit banning powers under the Credit Act in 2009. Prior to the enactment of the Credit Act, the only bans included in the Bans Register were occasional bans under state or territory legislation. Figure 5 (below) shows the number of credit bans per calendar year from 2001 to 2015.

The trend line in Figure 5 indicates that there has been an upward trend in the number of credit bans over time. The coefficient is +1.169748, indicating that the number of credit bans has increased at approximately 1.2 per year. This upward trend reflects the introduction of ASIC’s credit banning powers in 2009, rather than a pattern in the practice of enforcement.

Figure 5: Number of credit bans per calendar year from 2001 to 2015

4 Auditing of Self-Managed Superannuation Funds

There were 34 bans from being an approved self-managed super fund auditor

(‘SMSF bans’) during the six-year period from 1 January 2010 to 31 December 2015. The average number of SMSF bans per calendar year was 5.67, while the median number per calendar year was 5. Figure 6 (below) shows the number of SMSF bans per calendar year from 2010 to 2015.

The trend line in Figure 6 indicates that there has been a downward trend in the number of SMSF bans over time. The coefficient is –2.114286, indicating that the number of SMSF bans has decreased at approximately 2.1 per year. The small sample size (n = 34) and short time span (6 years) mean that it is not possible to identify any significant patterns in the use of SMSF bans. ASIC only acquired its SMSF banning power on 31 January 2013, thus it remains to be seen what patterns may emerge in its use of SMSF bans. Even though ASIC and the ATO are regarded as ‘co-regulators’ of SMSF auditors,[91] all of the bans prior to 2013 were by the ATO and all of those subsequent to 2013 were by ASIC, suggesting that, in practice, there may be a clearer division of responsibilities in relation to SMSF bans. The absence of SMFS bans in 2013 may perhaps result from a lag caused by handover of banning responsibilities from the ATO to ASIC.

Figure 6: Number of SMSF bans per calendar year from 2010 to 2015

This section continues the detailed empirical analysis of banning orders by reference to the duration of banning orders, presenting data on the total number of permanent and non-permanent bans, the number of permanent and non-permanent bans per calendar year, and the average and median duration of non-permanent bans.

There were 22 permanent company bans during the 29-year period from 1 January 1987 to 31 December 2015, which amounts to only 1.1% of the total number of 1992 company bans. This very low proportion of permanent bans is partly a reflection of the fact that the majority of company bans were administrative (estimated at 72.86%), rather than judicial, and that there is a fiveyear time limit on administrative company bans. However, it also suggests that the judiciary is more reluctant to impose permanent banning orders than ASIC, when compared with the high proportion of permanent financial bans (45%) and credit bans (59%), most of which were administrative bans by ASIC.

For non-permanent company bans, the average duration was 3.54 years, while the median was 3 years. The only notable trend with respect to the duration of non-permanent company bans is that there was an upward trend in the duration of the longest non-permanent banning order made during each calendar year.

The regular numbers from 1987 to 1994 in Figure 7 (below) reflect the period prior to which judicial company banning powers were introduced, when the only bans imposed were administrative bans subject to the legislative maximum of 5 years. The data suggests that, from 1994 onward, the judiciary gradually became accustomed to imposing longer company bans. However, overall, company bans tend to be considerably less severe than financial, credit and SMSF bans. Only 1.1% of company bans were permanent and the longest non-permanent company ban imposed in each year only rose above 10 years on 12 occasions (in 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2009, 2011, 2012, 2013 and 2014).

2 Financial Services

There were 300 permanent financial bans during the 24-year period from 1 January 1992 to 31 December 2015, which amounts to 45.45% of the total number of 660 financial bans. Figure 8 (below) shows the number of permanent and non-permanent financial bans per calendar year from 1992 to 2015, enabling an analysis of any correlations between the frequency of permanent and non-permanent bans.

Figure 8 indicates that there are no discernible trends in the number of permanent financial bans as compared with the number of non-permanent financial bans. The five years from 2006 to 2010 was the longest period during which the number of permanent bans was consistently lower than the number of nonpermanent bans. However, this period was directly followed by the period in which the number of permanent bans was consistently higher than the number of nonpermanent bans (2011 to 2014). Thus, there are no significant conclusions that can be drawn from this data as to temporal trends in the use of permanent and nonpermanent financial bans.

The average duration of non-permanent financial bans was 4.11 years, while the median was 3 years. The average duration of financial bans was only slightly higher than the average duration of company bans (3.54), even though administrative company bans are capped at a maximum of five years. This is a puzzling result, particularly when paired with the data showing that a significant proportion of financial bans were permanent (45.45%). What this suggests is that ASIC imposes either permanent or short financial bans, but rarely imposes non-permanent bans of a significant duration (for example, 20 or 30 years). This is confirmed by Figure 9 (below), which presents data on the longest nonpermanent financial ban imposed during each calendar year from 1992 to 2015.

Figure 7: Duration (in years) of the longest non-permanent company ban per calendar year from 1987 to 2015

Figure 8: Number of permanent and non-permanent financial bans per calendar year from 1992 to 2015

Figure 9 (below) indicates that the longest non-permanent financial ban was only 16 years (in 1994). In most years, the longest non-permanent financial ban was 10 years or less. It is unclear why there are no financial bans of a more significant duration (eg, 20 or 30 years), similar to some company bans imposed by the judiciary (see Figure 7 above). One potential concern with ASIC’s somewhat binary approach to imposing financial bans is that it lacks the proportionality that ought to be a feature of law enforcement of all kinds.[92] That is, the scale of the sanction ought to be proportionate to the scale of the wrongdoing. Presumably financial services misconduct exhibits a spectrum of seriousness, so it is not clear why the bans imposed in response to such misconduct do not also exhibit such a spectrum.

There were 54 permanent credit bans during the 15-year period from 1 January 2001 to 31 December 2015, which amounts to 59.34% of the total number of 91 credit bans. Figure 10 (below) shows the number of permanent and non-permanent credit bans per calendar year from 2001 to 2015, enabling an analysis of any correlations between the frequency of permanent and non-permanent bans. Figure 10 shows that, like financial bans, there are no particular trends in relation to the number of permanent credit bans as compared with the number of non-permanent credit bans.

The average duration of non-permanent credit bans was 6.15 years, while the median was 5 years. The average and median credit bans were slightly higher than the average and median financial bans (4.11 and 3 years). However, the same question arises regarding ASIC’s approach to imposing credit bans as arises regarding financial bans, which is why there are not more non-permanent credit bans of a significant, but not permanent, duration (for example, 20 or 30 years). Figure 11 (below) shows the longest non-permanent credit ban imposed during each calendar year from 2001 to 2015 (15 years), indicating that the longest non-permanent ban was 20 years and, in most cases, 10 or fewer years.

4 Auditing of Self-Managed Superannuation Funds

All of the 34 SMSF bans during the six-year period from 1 January 2010 to 31 December 2015 were permanent. This is because ss 130F and 131 of the SIS Act, unlike the company, financial and credit banning provisions,[93] only provide for permanent disqualification orders.[94] The introduction of permanent SMSF bans in 2009 forms part of an increasing trend in the overall number of permanent bans, due to the high proportion and increasing numbers of permanent financial and credit bans.[95]

Figure 9: Duration (in years) of the longest non-permanent financial ban per calendar year from 1992 to 2015

Figure 10: Number of permanent and non-permanent credit bans per calendar year from 2001 to 2015

Figure 11: Duration (in years) of the longest non-permanent credit ban per calendar year from 2001 to 2015

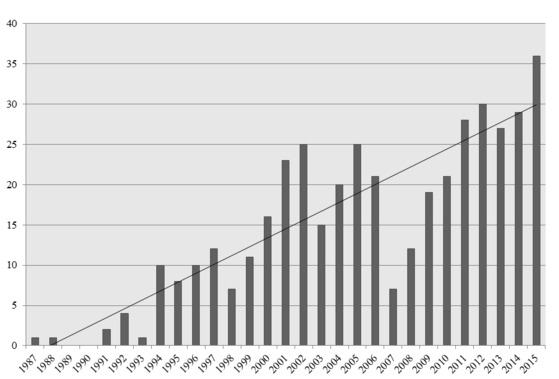

Figure 12: Number of permanent banning orders per calendar year from 1987 to 2015

5 Permanent Banning Orders

Figure 12 (above) presents the total number of permanent banning orders per calendar year (including all four categories of bans) from 1987 to 2015, showing that there is a clear upward trend in the number of permanent bans.

The trend line in Figure 12 below has a coefficient of +.856618, indicating that the number of permanent bans increased at approximately 0.8 per year. This pattern of increasing severity of banning orders, along with the increasing prevalence of bans relative to other major enforcement outcomes,[96] raises concerns regarding the accountability of banning practices, which predominantly involve administrative decision-making that is not subject to the rules of evidence that apply to judicial proceedings[97] and not able to be easily scrutinised by the public. These concerns, along with some suggestions for improved public accountability, are discussed in Part IV.

The empirical study presented in Part III shows that banning orders, the vast majority of which are administrative decisions by ASIC (an estimated 87% of banning orders are administrative), are increasingly prevalent relative to other major enforcement outcomes. The orders are also increasingly severe in their duration and may, in some instances, be imposed without sufficient regard for proportionality to the alleged misconduct. In the last 10 financial years, there were more banning orders (n = 1121) than all other major enforcement outcomes combined (n = 1068).[98] There has been an upward trend in the number of permanent banning orders over time, with a particularly sharp rise over the last nine years.[99] ASIC takes a somewhat binary approach to the imposition of financial and credit bans, usually either imposing quite moderate bans, ranging from one to five years, or permanent ones, with very few bans of an intermediate duration.[100] The increasing prevalence and severity of administrative banning orders, along with the lack of bans that are proportionate to intermediate instances of wrongdoing, raise significant concerns about ASIC’s accountability for its use of banning powers.

The judiciary has acknowledged that disqualification orders made by courts, while primarily protective in purpose, also function as a form of retribution akin to criminal punishment.[101] As McHugh J stated in Rich v ASIC,

the factors taken into account in the criminal jurisdiction – retribution, deterrence, reformation, contrition and protection of the public – are also central to determining whether an order of disqualification should be made under the Corporations Act and, if so, the appropriate period of disqualification. Those factors also support the conclusion that the jurisdiction exercised under this part of the Corporations Act cannot properly be characterised as purely protective.[102]

The punitive aspect of judicial disqualification orders was further elucidated by Finkelstein J in ASIC v Vizard:

It may be accepted that the principal object to be achieved by a disqualification order is protective: protection of the company and its shareholders against the likelihood of repetition of the offending conduct. The mistake is to treat this as the sole purpose of a disqualification order. That error has now been exposed. In Rich v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2004] HCA 42; (2004) 78 ALJR 1354 the High Court made it clear that a disqualification order can be imposed not only to protect the company’s shareholders against further abuse, but also by way of punishment and, importantly, for general deterrence. I am confident the fear of losing both their position from business life, as well as their good reputation, will be an effective deterrent in the case of many a director who is contemplating a dishonest course for gain.[103]

Some decision-makers contest the characterisation of judicial disqualification powers as partially ‘punitive’. Indeed, Kirby J dissented in Rich v ASIC partly on the basis that such powers do not have a punitive purpose.[104] Nevertheless, this is the dominant characterisation with regard to judicial powers. The situation is less clear with regard to the characterisation of administrative disqualification and banning powers. Some administrative decisions have adopted the majority opinion in Rich v ASIC that such powers are both protective and punitive,[105] while others have emphasised their protective purpose.[106] There is a complex constitutional question as to whether the characterisation of disqualification and banning powers as ‘punitive’ renders such powers unconstitutional on the basis that this involves conferring judicial power on executive bodies in breach of the separation of powers doctrine.[107] However, it is unnecessary to examine these issues for the purpose of this article, which is concerned with the practical adverse effects of banning powers, not with how their purposes ought to be characterised. The contention in this article is simply that all banning orders are punitive in effect, in the sense that, as Kirby J acknowledged in Rich v ASIC, ‘the order has a serious economic and reputational consequence for the officer who is disqualified’.[108]

The punitive effect of banning orders is widely recognised in academic literature. Even scholars who argue that the use of administrative banning powers for punitive purposes may be unconstitutional accept that such powers nonetheless have a ‘punitive effect’.[109] As noted in Part IIIA(1), the incapacitative nature of banning orders means they are typically regarded as among the more severe enforcement outcomes. For example, Ayres and Braithwaite, in their influential text Responsive Regulation: Transcending the Deregulation Debate,[110] suggest that ‘license suspension’ and ‘license revocation’ — which are similar in effect to banning orders — are, in fact, more severe enforcement outcomes than criminal penalties.[111] Ashworth explains that incapacitation is ‘usually confined to particular groups, such as “dangerous” offenders, career criminals or other persistent offenders’ and that the debate surrounding incapacitation as a sentencing rationale has ‘usually concerned lengthy periods of imprisonment and of disqualification (e.g. from driving, from working with children, from being a company director)’.[112]

He goes on to explain that

there is ... a principled objection to incapacitative sentencing[:] ... individuals are being punished, over and above what they deserve, in the hope of protecting future victims from harm ... it is essentially a moral objection to sacrificing one offender’s liberty in the hope of increasing the future safety of others.[113]

This comment encapsulates the inherently two-sided nature of incapacitative sanctions, which is that they are primarily aimed at protecting others, but effectively result in a substantial punishment for the individual who is considered a danger to others. A higher standard of public accountability is needed given the increasingly heavy use of administrative banning orders by ASIC — which have a similar punitive effect to criminal sanctions, but can be imposed more easily than criminal sanctions and in response to less serious misconduct.

ASIC’s administrative hearings, which are conducted by an ASIC staff member to whom the power to hold hearings under the ASIC Act has been delegated,[114] are not constrained by the rules of evidence and procedure that apply to judicial proceedings.[115] As stated in ASIC’s Hearings Practice Manual,

‘[i]n conducting a hearing the delegate exercises a true administrative function and not a quasi judicial function. It follows that the traditional rules of procedure of courts or quasi judicial bodies do not apply to our administrative hearings.’[116] ASIC’s ‘[g]uiding principles for conducting administrative hearings’, which may be varied or adapted to ‘deal with particular cases if that is appropriate’, provide that findings of fact must be based on ‘material that is relevant, credible and probative, but the rules of evidence do not apply’.[117] The principles go on to state that ASIC ‘will determine each matter on its merits. But in making a decision we are entitled to consider policy and precedent.’[118] In other words, administrative banning orders imposed by ASIC are imposed by way of a largely discretionary decision of an ASIC staff member, who may apply their own evidential standards, take into account policy considerations, and vary the principles for conducting administrative hearings where deemed appropriate.

In addition to banning orders being imposed via a largely discretionary process, the public cannot readily access information on the facts and reasons that form the basis for such orders.[119] During the course of the research undertaken to prepare this article, ASIC published the Bans Register on data.gov.au,[120] which was a commendable initiative, but there are still a number of hurdles in regard to public access to information on administrative banning orders imposed by ASIC.

First, it is not possible to access the certified banning orders in relation to an individual who has received a company ban or a financial ban — the two largest categories of bans — without paying a fee of $38.00 or more.[121] There is a question about whether this is consistent with the Government’s Public Data Policy Statement, which provides that Australian Government entities will ‘where possible, make data available with free, easy to use, high quality and reliable Application Programming Interfaces’ and ‘only charge for specialised data services and, where possible, publish the resulting data open by default’.[122] The Government’s Information Sheet on Charging for Data Services suggests that ‘specialised data services’ only include data provision services that require tailored processes or infrastructure in order to provide specific types of data.[123] This does not appear to be the case with regard to ASIC’s company and financial banning orders, which are already uploaded to ASIC’s online registers and available to download as soon as the fees are paid.[124] The banning orders in relation to credit bans and SMSF bans can currently be downloaded free-of-charge, suggesting that no additional infrastructure would be required to provide free-of-charge access to company bans and financial bans.

Second, subject to rare exceptions, the banning orders that can be downloaded from ASIC’s online registers do not contain written reasons for the orders. As a result, ASIC’s media releases are the only source of information on the facts and reasons that form the basis for banning orders imposed by ASIC. However, ASIC media release coverage is neither comprehensive nor detailed. As discussed in Part IIB, while media release coverage of financial and credit bans is quite good (above 90%), coverage of company bans — the largest category of bans — is less consistent (about 50%). It is often not possible for the public to obtain any information at all on the facts or reasons that give rise to company bans. Furthermore, while ASIC’s media releases provide a brief outline of the facts and alleged forms of misconduct that resulted in the banning order, they rarely provide detailed information on the delegate’s reasoning in imposing a ban of a particular type and duration.

The question of access to reasons for administrative banning orders may not simply be a matter of requiring regulators to provide the information to the public, in some instances it may also be a question of requiring them to produce it in the first place. The Corporations Act and Credit Act require ASIC to provide a statement of reasons to persons who receive financial and credit bans.[125] However, there is no requirement for ASIC to provide a statement of reasons in relation to company bans under s 206F of the Corporations Act,[126] and ss 131 and 130F of the SIS Act only require that reasons be provided where the regulator refuses an application to revoke a disqualification order.[127] Section 206F instead requires ASIC to provide a notice in the prescribed form requiring the individual to demonstrate why they should not be disqualified, attached to which are ASIC’s ‘concerns’ about the person’s conduct and the ‘documents on which [the] concerns are based’.[128] The lack of a statutory right to reasons for certain of ASIC’s administrative enforcement actions has been the subject of criticism.[129] It would further the aim of accountability if reasons were provided for all types of administrative banning orders, not only financial and credit bans.

Third, although it is now possible for the public to access the Bans Register on data.gov.au,[130] the Register, which is an Excel spreadsheet, is not easy to locate or user-friendly. The spreadsheet is not available on ASIC’s website, which instead redirects readers to ASIC’s datasets on data.gov.au.[131] Once the document has been located, there are a number of obstacles to interpreting its content, including: a lack of plain language headings; broadly categorised types of bans that are only briefly explained in an accompanying ‘Help File’;[132] the use of a blank end date to indicate permanent bans, rather than any express label to that effect; and thousands of duplicate entries as a result of bans being entered under different names and addresses. While making this data publicly available was a commendable initiative, there is a question as to whether the presentation of the data complies with the Government’s Public Data Policy Statement, which requires data to be made available with ‘easy to use, high quality and reliable Application Programming Interfaces’.[133]

In regard to ease of public access to information, the charging of fees, the failure to publish reasons, and the unhelpful user interface of the Bans Register place banning orders in stark contrast to other — considerably less frequently used — major enforcement mechanisms. Enforceable undertakings and infringement notices, with the exception of infringement notices for breach of continuous disclosure rules, are available free-of-charge on ASIC’s website via online registers that contain hyperlinks to the documents containing the reasons for the decisions.[134] Similarly, it is usually possible to obtain civil and criminal court judgments free-of-charge on the AustLII database, with the exception of lower court matters that are not typically published.

While ASIC is accountable for its use of banning orders via administrative and judicial review, as noted in Part II, it is widely accepted that ASIC ought also to also be accountable and transparent in the sense of being answerable to the public.[135] ASIC itself has regularly stated its commitment to this broader notion of accountability and transparency.[136] As noted in ASIC’s Statement of Intent, ‘ASIC appreciates the importance of transparency and accountability in ensuring our effectiveness as a regulator.’[137] In particular, ASIC emphasises the importance of transparency in regard to its enforcement activity: ‘[i]n our enforcement role, we are conscious of the need to be as transparent as possible in the decisions we make and the actions we take.’[138] ASIC has commented that it is ‘strongly committed to transparency in our enforcement and regulatory work, as demonstrated through the publication of regular enforcement reports’.[139] Relatedly, ASIC’s website states that it is ‘committed to promoting open data and all the advantages that it brings’.[140]

To give effect to the Government’s Public Data Policy Statement and ASIC’s commitment to accountability and transparency, and to ensure that there is a consistent level of transparency across ASIC’s different methods of enforcement, free-of-charge access to the certified banning orders and written reasons accompanying those orders ought to be made available to the public. Ideally, this would be in the form of an online, free-of-charge register of banning orders that can be browsed and searched using key terms and contains hyperlinks to the orders and reasons, similar to the register that already exists for enforceable undertakings, but with the addition of a search engine function. Importantly, the register ought to list both the name of the banned individual and the name of corporate entities with which they were relevantly affiliated, to enable users to search the register either by individual name or company name. The Corporations Act and SIS Act may need to be amended to provide for a statutory right to reasons in relation to company bans and SMSF bans, if the current documentation accompanying such bans does not provide an adequate level of transparency with regard to the facts and reasons leading to the ban. Additional funding ought to be provided to ASIC to cover lost revenue as a result of abolishing fees for company and financial banning orders and also to compensate for the administrative work of establishing and maintaining the proposed register, including any work involved in redacting reasons that contain personal or confidential information that is prohibited by law from being disclosed.

While there would be short-term costs involved in establishing the infrastructure to improve the transparency of ASIC’s banning practices, the longterm benefits are likely to outweigh such costs. There is now a large body of evidence indicating that open data adds significant value to the economy. Lateral Economics estimates the potential value of open data (including government, research, private and business data) to the Australian economy at up to $64 billion per annum,[141] while PwC estimates that data-driven innovation added an estimated $67 billion in new value to the Australian economy in 2013, leaving another $48 billion in unrealised potential value.[142] PwC concludes that ‘Government should prioritise the provision of open data as a key input for the Australian economy and provide senior political leadership to “get on with it” in order to support wider innovation by other players.’[143] The World Bank notes that

[w]hile sources differ in their precise estimates of the economic potential of Open Data, all are agreed that it is potentially very large ... [and] governments should consider how to use their Open Data to enhance economic growth, and should put in place strategies to promote and support the use of data in this way.[144]

A report by the Australian Bureau of Communications Research in February 2016, which estimates the value of open government data to the Australian economy at up to $25 billion per year, concluded that ‘[w]hile there is little consensus on the magnitude of the economic benefits of open government data sets, it is apparent that they provide substantial current and potential net benefits to the economy and society.’[145] The Bureau consulted with the Securities Industry Research Centre of Asia-Pacific (‘SIRCA’) in the process of preparing the report, which made the following comment in regard to ASIC’s data provision practices:

SIRCA believes ASIC’s current model of data provision is limiting innovation; information is only provided on the title of a document with a payper-view model for access. There is a significant information asymmetry here — only the holders of data know what is there, while the users don’t have the full picture. With limited information, the opportunities for innovation are not fully understood, and hence the potential business case for opening the data is limited. Fully readable and searchable data would be preferred, noting that similar institutions overseas do provide this service for free to encourage financial system innovation.[146]

In addition to the accountability[147] and economic benefits of providing improved public access to information in relation to ASIC’s most frequently used enforcement mechanism — banning orders — such access has the potential to advance two of ASIC’s key enforcement goals by better protecting financial investors and consumers, and deterring misconduct.[148] The proposed register of banning orders would enable investors and consumers to inform themselves as to whether the individuals and corporate entities with which they are dealing are or have been implicated in banning orders and in what capacity. The register would also send a strong message to current and prospective company directors, financial services providers, credit professionals and SMSF auditors that those who engage in misconduct risk not only being banned, but also suffering reputational damage as a result of increased public exposure of the ban. The deterrence value of transparency is recognised in ASIC’s enforcement policy: ‘[w]e will always assert the right to make an enforcement outcome public, unless the law requires otherwise. We will not agree to keep enforcement outcomes secret. This is important for regulatory transparency and effective deterrence.’[149]

Taking into account the frequency with which banning orders are imposed and the increasing severity of such orders, many of which are permanent, arguably banning orders have become the dominant mode by which corporate law is enforced in Australia. Despite the prevalence and power of this enforcement mechanism, it has been the subject of less academic scrutiny and public accountability than other — much less frequently used — enforcement mechanisms, such as civil and criminal court proceedings, enforceable undertakings and infringement notices. This article has, for the first time, brought detailed academic scrutiny to bear on the frequency and magnitude of banning orders imposed to prevent individuals from managing corporations, providing financial services, engaging in credit activities and auditing self-managed superannuation funds. There is insufficient transparency and accountability in relation to the use of banning orders, particularly given the punitive effect[150] of such orders and the fact that an estimated 87% of such orders result from administrative decisions that are unconstrained by the rules of evidence and procedure that govern judicial proceedings. The creation of an online register of banning orders would remedy the current information deficits — including the charging of fees, the non-publication of reasons, and the lack of a user-friendly interface — thereby giving effect to ASIC’s stated commitment to transparency and accountability, as well as the Australian Government’s Public Data Policy Statement and innovation agenda. This would bring appropriate accountability to bear on the most prevalent and powerful, yet least publicised, corporate law enforcement mechanism. It would also generate the economic benefits of open data, better equip investors and consumers to protect their financial interests, and harness reputational risk to increase deterrence of misconduct.

[∗] Research Fellow, Melbourne Law School, University of Melbourne, Australia. Funding for this research was provided by the Centre for International Finance and Regulation (Grant T021) and the University of Melbourne. The authors thank Dr Malcolm Anderson for conducting statistical analysis of data on banning orders, Helen Bird for collecting and analysing data on enforceable undertakings, Katharine Kilroy for collecting data on licence and registration suspensions and cancellations, and the anonymous referees for providing helpful comments.

[†] Senior Research Fellow, Melbourne Law School, University of Melbourne, Australia.

[‡] Harold Ford Professor of Commercial Law and Director of the Centre for Corporate Law and Securities Regulation, Melbourne Law School, University of Melbourne, Australia.

[1] See the references cited in below nn 2–6.

[2] The following journal articles contain empirical analyses of particular aspects of banning orders, but to the authors’ knowledge there has not yet been a comprehensive detailed empirical study on banning orders: Marina Nehme, ‘Latest Changes to the Banning Order Regime: Were the Amendments Really Needed?’ (2013) 31(6) Company & Securities Law Journal 341; Michelle Welsh, ‘Civil Penalty Orders: Assessing the Appropriate Length and Quantum of Disqualification and Pecuniary Penalty Orders’ (2008) 31(1) Australian Bar Review 96; Michelle Welsh, ‘Realising the Public Potential of Corporate Law: Twenty Years of Civil Penalty Enforcement in Australia’ (2014) 42(1) Federal Law Review 217; Michelle Welsh, ‘Civil Penalties and Responsive Regulation: The Gap Between Theory and Practice’ [2009] MelbULawRw 31; (2009) 33(3) Melbourne University Law Review 908; Ian Ramsay, ‘Increased Corporate Governance Powers of Shareholders and Regulators and the Role of the Corporate Regulator in Enforcing Duties Owed by Corporate Directors and Managers’ (2015) 26(1) European Business Law Review 49; Helen Bird et al, ‘Strategic Regulation and ASIC Enforcement Patterns: Results of an Empirical Study’ (2005) 5(1) Journal of Corporate Law Studies 191.

[3] See, eg, Jasper Hedges et al, ‘The Policy and Practice of Enforcement of Directors’ Duties by Statutory Agencies in Australia: An Empirical Analysis’ [2017] MelbULawRw 13; (2017) 40(3) Melbourne University Law Review 905; Welsh, ‘Civil Penalties and Responsive Regulation’, above n 2; Victor Lei and Ian Ramsay, ‘Insider Trading Enforcement in Australia’ (2014) 8(3) Law and Financial Markets Review 214; Helen Bird and George Gilligan, ‘Deterring Corporate Wrongdoing: Penalties, Financial Services Misconduct and the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth)’ (2016) 34(5) Company & Securities Law Journal 332; Michelle Welsh and Vince Morabito, ‘Public v Private Enforcement of Securities Laws: An Australian Empirical Study’ (2014) 14(1) Journal of Corporate Law Studies 39; Michelle Welsh, ‘The Regulatory Dilemma: The Choice Between Overlapping Criminal Sanctions and Civil Penalties for Contraventions of the Directors’ Duty Provisions’ (2009) 27(6) Company & Securities Law Journal 370.

[4] See, eg, Welsh, ‘Realising the Public Potential of Corporate Law’, above n 2; Hedges et al, above n 3; Jenifer Varzaly, ‘The Enforcement of Directors’ Duties in Australia: An Empirical Analysis’ (2015) 16(2) European Business Organization Law Review 281; Welsh, ‘Civil Penalties and Responsive Regulation’, above n 2; Lei and Ramsay, above n 3; Bird and Gilligan, above n 3; Welsh and Morabito, above n 3; Welsh, ‘Civil Penalty Orders’, above n 2; Bird et al, above n 2; Michelle Welsh, ‘Eleven Years On — An Examination of ASIC’s Use of an Expanding Civil Penalty Regime’ (2004) 17(2) Australian Journal of Corporate Law 175; George Gilligan, Helen Bird and Ian Ramsay, ‘Civil Penalties and the Enforcement of Directors’ Duties’ [1999] UNSWLawJl 3; (1999) 22(2) University of New South Wales Law Journal 417.

[5] See, eg, Helen Bird et al, ‘An Empirical Analysis of the Use of Enforceable Undertakings by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission between 1 July 1998 and 31 December 2015’ (Working Paper No 106, Centre for International Finance and Regulation, April 2016) 64–7 <http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2766134> Marina Nehme, ‘Enforceable Undertaking: A Restorative Sanction?’ [2010] MonashULawRw 19; (2010) 36(2) Monash University Law Review 108; Marina Nehme, ‘Enforceable Undertakings: A New Form of Settlement to Resolve Alleged Breaches of the Law’ [2007] UWSLawRw 4; (2007) 11(1) University of Western Sydney Law Review 104; Marina Nehme and Michael Adams, ‘The Active Use of Enforceable Undertakings by ASIC: Part 1’ (2007) 59(5) Keeping Good Companies 260; Marina Nehme and Michael Adams, ‘The Active Use of Enforceable Undertakings by ASIC: Part 2’ (2007) 59(6) Keeping Good Companies 326. See also Marina Nehme, ‘The Use of Enforceable Undertakings by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission’ [2008] UTasLawRw 10; (2008) 27(2) University of Tasmania Law Review 197; Christine Parker, ‘Restorative Justice in Business Regulation? The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission’s Use of Enforceable Undertakings’ (2004) 67(2) Modern Law Review 209; Tess Hardy and John Howe, ‘Too Soft or Too Severe? Enforceable Undertakings and the Regulatory Dilemma Facing the Fair Work Ombudsman’ (2013) 41(1) Federal Law Review 1.

[6] See, eg, Aakash Desai and Ian Ramsay, ‘The Use of Infringement Notices by ASIC for Alleged Continuous Disclosure Contraventions: Trends and Analysis’ (2011) 39(4) Australian Business Law Review 260; Reegan Grayson Morison and Ian Ramsay, ‘Enforcement of ASIC’s Market Integrity Rules: An Empirical Study’ (2015) 30(1) Australian Journal of Corporate Law 10; Ian Ramsay, ‘Enforcement of Continuous Disclosure Laws by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission’ (2015) 33(3) Company & Securities Law Journal 196; Marina Nehme, Margaret Hyland and Michael Adams, ‘Enforcement of Continuous Disclosure: The Use of Infringement Notice and Alternative Sanctions’ (2007) 21(2) Australian Journal of Corporate Law 112; Margaret Hyland, ‘Infringement Notices under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth): Has the Commonwealth Parliament Gone Too Far?’ [2008] UNDAULawRw 6; (2008) 10 University of Notre Dame Australia Law Review 115. See also Anne Rees, ‘Infringement Notices and Federal Regulation: Wolves in Sheep’s Clothing?’ (2014) 42(4) Australian Business Law Review 276.

[7] The data on enforcement outcomes other than banning orders has mostly been sourced from ASIC’s annual reports, which are available from 1997–98 onward: see ASIC, ASIC Annual Reports <http://asic.gov.au/about-asic/corporate-publications/asic-annual-reports/> .

[8] See Part IIIA.

[9] The Financial System Inquiry found that ‘[t]he public expectation is that ASIC will act as a proactive watchdog in supervising all financial services provided. However, in practice, ASIC has a very wide remit but limited powers and resources’: Financial System Inquiry, Final Report (November 2014) 236 <http://fsi.gov.au/publications/final-report/> . Similarly, the Senate Inquiry into the Performance of ASIC found that ‘ASIC’s long list of regulatory tasks and the resources available to ASIC to perform these tasks clearly act as constraints on its ability to meet expectations the public and stakeholders may have’: Senate Economics References Committee, Parliament of Australia, Performance of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (2014) 414 [25.52]. The Senate Inquiry noted at 397 [25.6] that

Many individuals and organisations agreed that ASIC is currently underfunded. A view also frequently expressed was that ASIC’s expanded regulatory remit had negatively affected ASIC’s performance. This was either as a logical consequence of ASIC having a longer and more diverse list of responsibilities, or because the additional funding provided to supplement specific new responsibilities has been insufficient.

The ASIC Capability Review, commissioned by the Australian Government, had a different view. Despite acknowledging ‘a general and widespread belief that ASIC is underfunded’ and ‘that ASIC has experienced difficulties in adjusting to a lower level of funding resulting from government savings measures imposed since a high point in funding in 2009–10’, the Review Panel concluded that ‘it does not necessarily follow that ASIC is “under-funded”’ and that ‘ASIC’s funding has increased with the expansion of its mandate’: ASIC Capability Review Panel, Fit for the Future: A Capability Review of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (December 2015) 136–7 <https://static.treasury.gov.au/uploads/sites/1/2017/06/ASIC-Capability-Review-Final-Report.pdf>.

[10] See Part IIB.

[11] ASIC, Annual Report 2014–2015 (15 October 2015) 10 <http://download.asic.gov.au/media/ 3437945/asic-annual-report-2014-15-full.pdf> . See also Welsh, noting that administrative banning orders under s 206F of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (‘Corporations Act’) are ‘quicker and cheaper’ than civil disqualification orders under s 206C: ‘Civil Penalties and Responsive Regulation’, above n 2, 928–9.

[12] See Part II for an explanation of how ‘banning orders’ are defined in this article and the legislative provisions under which such orders were made during the study period.

[13] See Part IIIB. The data on SMSF bans was sourced from ASIC, Banned and Disqualified Persons Dataset <https://www.data.gov.au/dataset/asic-banned-disqualified-per>, rather than directly from ASIC.

[14] See Part IIIB.

[15] See Part IIIC.

[17] See Robert P Austin and Ian M Ramsay, Ford, Austin and Ramsay’s Principles of Corporations Law (LexisNexis Butterworths, 2015) 104–5, 265–6; Rich v ASIC [2004] HCA 42; (2004) 220 CLR 129, 148–57 [41]–[59]; ASIC v Vizard [2005] FCA 1037; (2005) 145 FCR 57, 65 [35]. For further discussion of the extent to which banning orders ought to be characterised as partially ‘punitive’ sanctions, see below nn 102–114 and accompanying text.

[18] ASIC Act s 59(2)(a); ASIC, Regulatory Guide 8: Hearings Practice Manual (March 2002) 7 <http://download.asic.gov.au/media/1236863/rg8.pdf> .

[19] See Part II and Part IV.

[20] See Part IV.

[21] See Part IV; Australian Government, Australian Government Public Data Policy Statement

(7 December 2015) <https://www.dpmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/publications/aust_govt_public_

data_policy_statement_1.pdf>; Bureau of Communications Research, Department of Communications and the Arts (Cth), Open Government Data and Why it Matters Now (8 February 2016) <https://www.communications.gov.au/departmental-news/open-government-data-and-why-it-matters-now>.

[22] ASIC, Laws We Administer <http://asic.gov.au/about-asic/what-we-do/laws-we-administer/> .

[23] ASIC, Strategic Framework <http://asic.gov.au/about-asic/what-we-do/our-role/strategic-framework/> .

[24] ASIC, Annual Report 2015–2016 (14 October 2016) 2 <http://download.asic.gov.au/media/4058626/ asic-annual-report-2015-2016-complete.pdf> .

[25] ASIC, Information Sheet 151: ASIC’s Approach to Enforcement (September 2013) 1 <http://download.asic.gov.au/media/1339118/INFO_151_ASIC_approach_to_enforcement_20130916.pdf> .

[26] ASIC, ASIC Enforcement Outcomes <http://asic.gov.au/about-asic/asic-investigations-and-enforcement/asic-enforcement-outcomes/> .

[27] ASIC, Annual Report 2016–2017 (5 October 2017) 26 <http://download.asic.gov.au/media/4527819/

annual-report-2016-17-published-26-october-2017-full.pdf>.

[28] See, eg, Margaret Hyland, ‘Is ASIC Sufficiently Accountable for its Administrative Decisions?