Sydney Law Review

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Sydney Law Review |

|

Serious Hardship Relief:

In Need of a Serious Rethink?

Kevin O’Rourke,[1] Ann Kayis-Kumar[1]† and Michael Walpole[1]‡

Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic and its economic aftershocks have put into strong focus the tax issues faced by financially vulnerable individuals and small business. With this economic backdrop, it is likely that more taxpayers will be in severe financial stress, which will in turn increase the need for release from tax debts on grounds of serious hardship. However, these provisions are outdated and in urgent need of reform. This article outlines their legislative background and the regulatory landscape, and explores the systemic issues faced by taxpayers in litigating serious hardship cases. Further, it makes four key recommendations to modernise the current tax policy and law, and the design of these provisions. These recommendations are designed to attain better outcomes for financially vulnerable individuals and small businesses while also maintaining trust and confidence in the Australian Taxation Office among the wider community.

Even before the COVID-19 outbreak in Australia, researchers estimated that 11% of the Australian population were experiencing severe or high financial stress.[1] Regardless of socio-economic grouping, between 30.1 and 40.6% of financially vulnerable people assisted by the financial counselling sector were not able to access the tax advice they needed.[2] These financially vulnerable people most often needed assistance with outstanding tax returns and tax debt collection matters.[3]

People experiencing financial hardship are at a further disadvantage as the fact of outstanding tax returns often prevents access to the full range of welfare benefits and COVID-19 financial relief packages offered by the Australian Government. It is not surprising that registered tax agents refuse to assist this cohort out of fear that the client is too far in debt to be able to pay the agent’s fees at the end of the engagement. This presents an access-to-justice issue for financially vulnerable people and small businesses.

Leading economists[4] and social impact sector experts[5] expect that many individuals and small businesses will be faced with a financial cliff upon termination of COVID-19 government financial support in March 2021,[6] further exacerbating pre-existing problems and amplifying financial stress.

As a result of COVID-19, we anticipate that many people in severe and high financial stress will be pushed deeper into severe financial stress in the short-term. This would, in turn, have medium-to long-term consequences for socio-economic disadvantage, including increasing the need for release from tax debts on grounds of serious hardship.

For over 100 years there has been a discretion in taxation legislation to release taxpayers from tax-related liabilities on the ground they would otherwise suffer serious hardship. Despite its long history, there is a relative dearth of literature on the serious hardship relief provisions in Australia. The existing literature on serious hardship has, to date, focused on: examining the statutory sources of power, judicial precedent, and administrative guidance;[7] exploring the debt collection framework of the Australian Taxation Office (‘ATO’) and offering proposals to address existing weaknesses;[8] and, analysing the impact of the ATO’s debt collection practices on procedural justice and perceptions of fairness.[9]

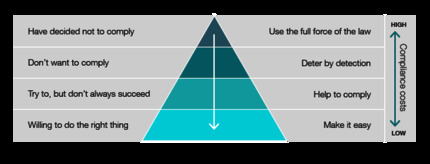

By comparison, the literature on debt collection and compliance contains a wealth of insights.[10] The historical origins of its cooperative compliance model (Figure 1) exemplifies the ATO’s ability to move away from a one-size-fits-all approach to tax admi[11]stration11 and take steps to mitigate harm to the ATO’s reputation arising from community perceptions of its debt collection [12]actices.12 As observed by scholars such[13]s Whait,13 the compliance model is consistent with the principles of responsive regulation and makes a clear distinction between taxpayers who are non-compliant due to various mitigating circumstances as opposed to taxpayers who are deliberately non-compliant.

Figure 1: Australian Taxation Office Compliance Model[14]

A continual process of gauging and adapting to the community’s expectations is vital to maintaining trust and confidence, and protecting the ATO from reputational harm.

This article posits that the serious hardship relief landscape has not adequately adapted to the community’s expectations on a number of aspects including: the impact of tax debts and debt collection on taxpayers’ mental health;[15] the futility and cost of chasing uncollectable debt;[16] the imperative that the ATO continue to foster willing participation in the tax system; and relief for those who have generally participated in the tax system, but may have dropped out due to health shocks or other shocks (such as loss of employment, business failure, relationship breakdown). Once these concerns are taken into account and considered by reference to the underlying rationale for tax debt forgiveness, the need for reform of the current provisions becomes clearer.

Accordingly, Part II of this article identifies current legislative and regulatory constraints on serious hardship relief. Part III considers systemic issues in litigating serious hardship cases and Part IV makes recommendations that, if adopted, would modernise the design and operation of the serious hardship provisions. Part V concludes the article.

Only the Australian Government Finance Minister has the power to permanently extinguish a debt due to the Commonwealth.[17] The Commissioner of Taxation has a general power of administration in relation to various taxation laws,[18] pursuant to which they can settle disputes and choose not to pursue uneconomic debts.[19] Additionally, the Commissioner will not seek to recover a debt that is irrecoverable at law, such as through extinguishment.[20] This article is concerned with a separate and specific statutory power enabling the Commissioner to release taxpayers from tax-related liabilities on the ground that they would suffer ‘serious hardship’.

The phrase ‘serious hardship’ has a lengthy legislative history.[21] It first appeared in s 64(1) of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1915 (Cth) as follows:

In any case where it is shown to the satisfaction of the Commissioner that a taxpayer liable to pay income tax has become bankrupt or insolvent, or has suffered such a loss that the exaction of the full amount of tax will entail serious hardship, [the] Board ... may release such taxpayer wholly or in part from his liability ...

Section 97 of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1922 (Cth) was expressed in similar terms, but extended to cover the executor or administrator of a deceased person. Under both provisions, the ‘Board’ consisted of the Commissioner, the Secretary to the Treasury and the Comptroller-General of Customs.

Former s 265 of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (Cth) (‘ITAA36’) was also expressed in similar terms, but applied to ‘persons’, which effectively extended the relief to companies.[22] The references to bankruptcy and insolvency were omitted, and the Board now consisted of the Commissioner, the Secretary of the Department of Finance and Administration and the Chief Executive Officer of the Australian Customs Service.

According to the Explanatory Memorandum that accompanied the Income Tax Assessment Bill 1935 (Cth), the removal of the reference to bankruptcy was because ‘the term “serious hardship” now qualifying the whole clause is an all embracing provision’.[23] As will be seen below, that is at odds with the interpretation of the current provision.[24]

The Board had a busy workload. For the 2002–03 tax year, the Board considered 1,798 release applications. Of those applications, 636 were granted a full release, 270 a partial release, 835 were refused and 57 were either deferred or withdrawn. Approximately 30% of release applicants were small businesses.[25]

As noted by Fisher, responsibility for administering the hardship provisions was transferred to the ATO in 2003, and occurrences of granting relief have risen in the period from 2003 to 2010.[26] This trend appears to have continued into the next two financial years, with 2,439 and 2,525 full or partial debt releases granted in the years 2011–12 and 2012–13, respectively.[27] However, aggregated data on the number of requests for relief and the quantum of relief granted since 2012–13 does not appear to be publicly available.

Since 1 September 2003, the discretion exercisable by the Commissioner to release taxpayers from tax-related liabilities on the ground that they would suffer serious hardship has been granted pursuant to s 340-5 of sch 1 to the Taxation Administration Act 1953 (Cth) (‘TAA’): ‘[y]ou may apply to the Commissioner to release you, in whole or in part, from a liability of yours if section 340-10 applies to the liability’.[28] That application must be in the approved form.[29] Relevantly, the Commissioner ‘may release you, in whole or in part, from the liability’ if you are an individual and ‘would suffer serious hardship if you were required to satisfy the liability’.[30]

Section 340-10 of sch 1 to the TAA applies to income tax, fringe benefits tax (‘FBT’) (including instalments), Medicare levy, Pay As You Go (‘PAYG’) instalments, and related General Interest Charge (‘GIC’) and penalties. Unless the tax is listed in the section it is not eligible for release. One notable exclusion is Goods and Services Tax (‘GST’), which can affect small business applicants in particular. In Burns and Commissioner of Taxation,[31] for example, the applicant was a floor installer who operated as a sole trader. More than half of his taxation liabilities related to GST, but these liabilities were not eligible for release. This is particularly problematic because observations of participants in the National Tax Clinic Program include that financially vulnerable small businesses (including sole traders) are, on average, seven years behind on lodgement of their Business Activity Statements (‘BAS’).[32] For completeness, a BAS is an ATO-approved form issued to all GST-registered entities. The form includes the GST return that each registered entity is required to lodge and discloses all GST-related liabilities and entitlements.

As with the predecessor provisions discussed in Part II(C) below, serious hardship is now the sole criterion for deciding whether release of a tax debt should be granted. However, three significant changes were made in 2003. First, the merits of the Commissioner’s decision became reviewable by the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (‘AAT’). Previous challenges to decisions of the Boards had to be by way of judicial review. Second, the relief that previously extended to companies was abolished.[33] The Explanatory Memorandum which accompanied the new measures was silent on the reasons for this change. Third, the scope of the release arrangements was expanded to cover instalments of PAYG and FBT.

Academics such as Fisher[34] have observed that while the threshold test turns on the criterion of ‘serious hardship’, the legislation remains silent on the issue, providing no definition or criteria as to what may constitute serious hardship. Similarly, the Explanatory Memorandum accompanying the Taxation Laws Amendment Bill (No 6) 2003 (Cth) contains no interpretive guidance.[35] Thus, the meaning of serious hardship is interpreted by reference to judicial considerations and administrative guidance, outlined below.

The meaning of serious hardship has been considered in numerous decisions of the AAT and the Federal Court of Australia. Earlier Federal Court decisions under former s 265 of the ITAA36 remain relevant because, according to Deputy President Forgie of the AAT, ‘the power given to [the] Board was similar to that given to the Commissioner in section 340-5(3). For present purposes, what appears in Items 1 and 2 of section 340-5(3) correlates with what appeared in sections 265(1)(a) and (b)’.[36]

In Powell v Evreniades, Hill J explained that the expression ‘serious hardship’ is an ordinary English expression,[37] and that hardship that is ‘serious’ can be something less than ‘extreme’:

Clearly there would be serious financial hardship if the dependants of a deceased person were left destitute without any means of support. That is not to say that in any particular case something less than that will not constitute serious hardship.[38]

There is a two-stage process described by Hill J as follows:

As the language of s 265 discloses, ... the Board acting under s 265 must proceed in two steps. Where, as here, the case is one arising after the death of a taxpayer the Board must first decide whether owing to the death of the original taxpayer that person's dependants are in such circumstances that the exaction of the full amount of tax would entail serious hardship. If that question is answered favourably to the applicant for relief the Board must then address the next set of issues, namely whether there should be release in the circumstances and if so whether that release will be of the whole or part of the liability. It is obvious that the factors that may be relevant to the second of these steps could be a great deal wider than the factors which are relevant to the first of the steps.[39]

The Federal Court has also referred with approval to the description of the ‘two stage process’ discussed by Member Trowse in the AAT:

In the Tribunal’s opinion, the language of the legislation requires a two stage approach. First, the decision-maker must decide whether the settlement of the liability will result in serious hardship. If that decision is favourable to the applicant, the discretion offered by sub-section 340-5(3) then falls for consideration.[40]

The Commissioner of Taxation’s policy on the application of s 340-5 is explained in a practice statement entitled ‘Debt Relief, Waiver and Non-pursuit’.[41] Although the policy is not strictly binding on the AAT, it has regard to the policy in making its decisions.[42]

The Practice Statement has been referred to with approval by Deputy President Forgie of the AAT in the following terms:

In the Policy, the Commissioner has addressed the concept of serious hardship in terms that I find are consistent with s 340-5(3), the TAA and the more general taxation law of which it is a part. What the Commissioner has gone on to do is to set out a 3-step approach to determine whether a person is suffering serious hardship.[43]

Under the Practice Statement, the Commissioner considers serious hardship ‘to exist where the payment of a tax liability would result in a person being left without the means to afford basics such as food, clothing, medical supplies, accommodation or reasonable education’.[44]

The Commissioner applies three tests in evaluating whether serious hardship exists: the income and outgoings test; the assets and liabilities test; and other relevant factors.[45] Each test needs to be satisfied. According to the Commissioner, the object of the tests ‘is to determine whether the consequences of paying the tax would be so burdensome that the person would be deprived of what are considered necessities according to normal community standards’.[46] These three tests are outlined below.

(a) The Income and Outgoings Test

The income and outgoings test takes into account household income and expenditure as well as the taxpayer’s capacity to pay in a reasonable timeframe. It also considers any scope for the taxpayer to increase their income, whether all expenditure could be considered reasonable, and whether the taxpayer has made attempts to defer or reschedule other financial commitments.[47]

In assessing serious hardship, it is appropriate to consider the full resources of the household, rather than just the resources of the applicant:

[T]he determination of whether the exaction of the full amount of the tax would entail serious hardship properly involves a consideration of the financial affairs of the taxpayer, including his financial relations with the other members of his household, and with any family company.[48]

This issue arose in Burns.[49] The applicant lived with his de facto partner and argued that the Commissioner’s application of the income and outgoings test was flawed because it included 100% of his partner’s income. The AAT rejected the argument stating that ‘it is reasonable to expect her to contribute to household expenses in proportion to her income’.[50] The applicant also argued that a period of some 3.8 years to pay off his taxation liability was unreasonable. The AAT disagreed, noting that the applicant was a relatively young man with no dependants.[51]

Sometimes income simply exceeds expenditure and can be used to pay off taxation debts. In Power and Commissioner of Taxation,[52] the applicant’s outstanding tax liabilities amounted to $57,566. Based on his own figures, he had a fortnightly surplus of income less expenditure of $422. According to the AAT, the applicant had the capacity to pay over time, which, again on his own figures, would take approximately five years to pay the current liability. However, as his expenses were overstated and there was room to reduce discretionary spending, it should not take this long. Accordingly, this was not a case of serious hardship.[53]

Having to live on the age pension does not of itself amount to serious hardship. In Schweitzer and Commissioner of Taxation[54] the applicant was married and she and her husband each received an age pension that, at the time of the hearing, was a combined fortnightly payment of $1,296. Their estimated fortnightly expenses were $1,321.

In responding to a submission that the applicant could sell the family home, Deputy President Forgie stated:

[The applicant] and her husband would no longer have to pay rates on the ... property and that amount would contribute to the rent. [The applicant] would be living the life that many people receiving an Age Pension must live. Those on the Age Pension living in rental accommodation are not, by reason of that fact alone, regarded as suffering serious hardship. If she were required to contribute a significant sum from her Age Pension each fortnight, I might have a different view.[55]

In assessing income and outgoings, the applicant’s expenditure must be reasonable. In Re Moriarty and Commissioner of Taxation, the Commissioner referred to the applicant’s unusually high level of discretionary spending, including on holidays, dining out, and entertainment, which could be reduced.[56] The applicant did not agree with the Commissioner’s description, pointing out, among other things, that he had only taken two holidays in seven years. However, the AAT agreed with the Commissioner’s description of the applicant’s discretionary spending and also that what he was previously paying by way of rent was unreasonable.[57]

Leaving to one side considerations such as the reasonableness of expenditure, the analysis of an applicant’s income and outgoings by the AAT has largely affirmed that an applicant who is not reasonably capable of satisfying taxation debts from his or her net income is thus suffering serious hardship.

(b) The Assets and Liabilities Test

The assets and liabilities test takes into account a taxpayer’s equity in, or access to, assets that may be indicative of their capacity to pay. Consideration is given to any property owned wholly or jointly by the taxpayer and their partner, privately or within a business structure.

The Commissioner does not expect taxpayers to surrender ‘normal and reasonable possessions’ to pay tax debts, including the taxpayer’s home, a motor vehicle, furniture and household goods, tools of trade, and cash-on-hand sufficient to meet immediate day-to-day living expenses.[58]

The issue that arises most often here is whether the applicant needs to sell the family home. The following two AAT decisions cast light on when a home should be sold. In Schweitzer,[59] the applicant’s assets were not sufficient to cover her tax-related liabilities, which were substantial and exceeded $7 million. Her assets included a home valued at over $1.3 million. Deputy President Forgie observed: ‘would the loss of her ... property in which she lives ... amount to serious hardship within the meaning of Item 1 of s 340-5(3)? I think that it does not’.[60]

In Lau and Commissioner of Taxation,[61] the applicants jointly owned a luxury apartment in a prestige location in the central business district. The AAT noted that the applicants may well have been correct in saying that the apartment may not reach the suggested value of $3.5 million. Nevertheless, the property could not be regarded as a residence of modest value.[62]

The analysis of an applicant’s assets and liabilities by the AAT, as with the income and outgoings analysis, again largely affirms that an applicant who is not reasonably capable of satisfying taxation debts from his or her net assets is suffering serious hardship. The exclusion of the family home as an asset, if of a reasonable nature, is significant in that analysis. There is little guidance, however, on what constitutes a ‘reasonable’ home.

(c) Other Relevant Factors Test

In circumstances where a taxpayer can demonstrate that serious hardship may be caused by payment of their liability, the Commissioner may on discretionary grounds decide against granting release, such as where:

• a taxpayer appears to have unreasonably acquired assets ahead of meeting their tax liabilities

• a taxpayer appears to have disposed of funds or assets without giving consideration to their tax liability

• release would not alleviate hardship, such as where the person has other liabilities or creditors

• a taxpayer has paid other debts (either business or private), in preference to their tax debt

• the taxpayer, without good reason, has not pursued debts owed to them

• serious hardship is likely only to be short term (which is determined on a case by case basis)

• the taxpayer has a poor compliance history

• the taxpayer is unable to show that they have planned for future debts

• the taxpayer has structured their affairs to place themselves in a position of hardship (for example, placing all assets in trusts or related entities over which they have control)

• the taxpayer has delayed lodgement of returns resulting in the accumulation of a large debt that they are unable to pay.[63]

Additionally, the Commissioner must make a decision about the extent to which, if any, release should be granted: ‘Release from the full amount of the liability would not generally be appropriate where partial release is sufficient to avoid serious hardship.’[64]

It will be recalled that the Commissioner of Taxation may release you from a tax liability if you would suffer serious hardship if required to satisfy the liability.[65] It is said that this establishes a causal relationship between the requirement to satisfy the tax liability and the serious hardship. However, it seems an extraordinary proposition that the more serious the financial hardship generally the less likely it is that release of the tax debt will be granted. That a causal relationship exists was affirmed by Deputy President Forgie in Re Rasmussen and Commissioner of Taxation:

Even if [the Applicant] and his wife were to sell the former family home ... he is likely to continue to face serious hardship but it is not serious hardship that arises from his being required to satisfy his tax liability. It is serious hardship that arises because his liabilities, of which his tax liability is but one, exceed his assets and the outgoings required to service those liabilities exceed his income. It is not serious hardship that [the Applicant] would suffer because he is required to satisfy his tax liability. That means that [the Applicant] does not meet the criterion in item 1 of s 340-5(3) of Sch 1 of the TAA. As he does not meet that criterion, I do not have power to release him from whole or part of his tax liability.[66]

It should be immediately observed that this is not part of the exercise of a discretionary power, as will be discussed in more detail below, but is a statutory criterion that must be satisfied if release is to be granted. The application of this criterion in individual cases might be viewed as leading to harsh outcomes.

There are numerous AAT cases illustrating the point. For example, in XLPZ and Commissioner of Taxation,[67] the applicant was unemployed and separated from his former wife. Protracted litigation with his former wife over access to his sons had left him ‘in ruinous financial circumstances’.[68] His taxation debt related to his income tax liabilities and arose because of his early access to superannuation benefits to meet legal expenses associated with Family Court proceedings.

The applicant’s taxation debt was $57,939 and, on his own figures, his liabilities exceeded assets by at least $300,000. His monthly expenses were capable of being met only through a combination of his Newstart allowance and regular advances from his father. The AAT refused relief on the basis that the applicant would still suffer serious hardship because of his other financial commitments.[69]

A rationale for this criterion can be found in the Explanatory Memorandum that accompanied the 2003 legislative changes:

Release would not normally be granted where it would not relieve hardship. A common example would be where the existence of other creditors made bankruptcy inevitable and granting release from tax liabilities would merely assist those other creditors at the expense of the Commonwealth.[70]

In Re Thomas and Commissioner of Taxation, Deputy President Forgie refused relief on the same basis:

[T]he release of [the applicant] from the tax related liability ... will not alter his situation. He will be in precisely the same position. His liabilities will still exceed his assets. Any one of his creditors could take steps to institute proceedings leading to his becoming bankrupt whether he is released from that sum or not. If he were to be released and one was to do so, the outcome would be that no part of the amount that was released could be recovered in the bankruptcy. That would be to the detriment of the Australian community.[71]

Nevertheless, we respectfully contend that the proposition is unsound for the following four reasons.

First, the proposition is not supported by the history of the legislative provision. As was discussed above, the phrase ‘serious hardship’ appeared in income tax legislation in 1915 and 1922. The removal of the reference to bankruptcy in the ITAA36 was because the term ‘serious hardship’ was considered to be ‘an all embracing provision’.[72] Apart from the statement extracted above from the Explanatory Memorandum, there is nothing to suggest that the meaning of the term changed when div 340 was inserted into the TAA in 2003.

Second, it is entirely possible that the drafters of the Explanatory Memorandum misstated the law. As Wigney J recently cautioned in the Federal Court,

[u]ltimately, the task of statutory construction must begin and end with a consideration of the text itself ... The Explanatory Memorandum cannot supplant the text of the relevant provisions. It is also the case that sometimes Explanatory Memoranda misstate the law.[73]

Third, there seems a lack of logic in refusing release from a taxation debt owed by a taxpayer suffering serious hardship on the ground that their hardship is too serious to warrant release.

Finally, refusing relief on the basis that the applicant would still suffer serious hardship because of their other financial commitments is disconnected from the realities of financial vulnerability for many taxpayers. Tax debts are often a sub-component of overall debts. This has recently been shown empirically with researchers finding that, regardless of socio-economic grouping, 30.1–40.6% of financially vulnerable people seeking assistance from financial counsellors also need independent tax advice, but are unable to access it.[74] Of these taxpayers, nearly all (that is, 88%) need assistance with tax debt discussions.[75]

Given these considerations, Part IV(A) proposes a solution to this issue that both ensures that relief is available in appropriate cases and that the Commissioner is not,

in the event of a later bankruptcy or insolvency, prejudiced in having granted relief.

Section 340-5(3) states that the Commissioner ‘may’ release you from the liability. The question of whether this was a mandatory or discretionary power was discussed by Hill J in Powell in the context of former s 265 of the ITAA36, in which his Honour noted the difficulty in reading ‘may’ as being mandatory:

One difficulty with such an interpretation however, would be that it leaves open the question of what the Board is in fact bound to do, given that under the section it has a choice to remit the tax in whole or in part. Therefore the word ‘may’ presumably encompasses that choice which lies in the discretion of the Commissioner.[76]

When exercising a discretion, it is important for a decision-maker to have regard to all relevant factors. In the context of serious hardship, the following eight factors have received prominence in AAT decisions:

(1) Disclosure and dishonesty.

(2) Tax compliance history.

(3) Availability of payment arrangements with the Commissioner.

(4) Giving priority to expenditure other than tax liabilities.

(5) Giving priority to creditors over the Commissioner.

(6) Possible bankruptcy of the applicant.

(7) Inheritances.

(8) The misfortune is of the applicant’s own making.

The remainder of Part II(E) explores each of these factors.

1 Disclosure and Dishonesty

The importance of making full disclosure to the AAT was emphasised in Thomas:

Review of an application to release a tax-related liability is a situation in which the facts relating to an individual’s income, expenditure, assets and debts will usually be peculiarly within the possession and knowledge of that individual and not of the Commissioner. It is the task of the individual, and not that of the Commissioner, to gather together and produce all relevant material.[77]

In Lau,[78] the AAT concluded that the applicants failed to make full disclosure about their financial circumstances and, further, that the information the applicants did provide was not correct, but rather in the nature of assertions contradicted by the documentary evidence.[79] Additionally, the applicants had significantly understated income on tax returns by amounts ranging from $74,552 to $2,353,369.[80] These were all factors that weighed against release.

In Schweitzer,[81] the applicant’s tax-related liabilities exceeded $7 million. The Commissioner submitted that the applicant had been dishonest in lodging tax returns that substantially understated her taxable income over a 12-year period, giving false evidence to the AAT in income tax review proceedings in relation to the ownership of a property, and omitting to reveal her interest in her late mother’s estate when making her application for release.

Deputy President Forgie, while not making specific findings on all contentions, found that

she tried to conceal her interest in her late mother’s estate from the Commissioner. Furthermore, she has not taken reasonable steps to put herself in a position where she would receive her inheritance so that she could reduce her debt to the Commissioner.[82]

This was a factor against exercising the discretion to release her from tax liability.

Even conduct less than dishonesty might still weigh against an applicant. In ZDCW and Commissioner of Taxation,[83] the applicant’s household’s combined assets had a value of $843,699, with liabilities of $225,000, leaving a balance of $618,699. On this basis, the Commissioner contended that the applicant and his wife had sufficient equity to discharge his income tax liability. The applicant contended that, as a result of mortgages over two properties in favour of his wife, he was unable to dispose of either property to raise any amount to pay the taxation liability.

Some two months before his release application, the applicant and his wife entered into a ‘Contractual Will Arrangement’ by executing: (1) a Deed for Contractual Will; (2) an Option Deed granting the applicant’s wife an option to purchase the applicant’s share of each property for $1 if any of a series of defined default events occurred; and (3) mortgages in favour of the applicant’s wife over the applicant’s interest in the two properties, securing her rights under the Deed for Contractual Will and Option Deed.

The AAT was not satisfied that the applicant was under any obligation to enter into the Contractual Will Arrangement. Nor was the AAT satisfied that his wife would seek to enforce her rights under that arrangement in the face of recovery action by the Commissioner against the applicant or that the properties would not be available to him to meet his tax liability.[84]

The Commissioner submitted that the Contractual Will Arrangement appeared to be a conscious attempt to put assets beyond the reach of the Commissioner. Although that was not a finding the AAT was prepared to make without first hearing the applicant or his wife give evidence on the point, it did find ‘that the arrangement was entered into by the applicant without making provision to meet his tax liability’,[85] and that was sufficient for relief to be refused.

2 Tax Compliance History

Somewhat related to honesty and disclosure is an applicant’s tax compliance history. In Burns, the applicant had a poor compliance history, especially for BAS lodgments in the financial years 2010 through to 2017.[86] He submitted that there were mitigating factors, including personal injury, alcohol dependence and relationship issues, especially from 2014 onwards.[87] The AAT concluded that this history weighed against the exercise of the discretion to release the applicant from his taxation liability and concluded that ‘the Applicant’s poor compliance history is somewhat mitigated, but not cancelled out entirely, by these unfortunate personal circumstances’.[88] This seemed to be so even though some taxation liabilities on the BASs, being GST, were not eligible for release.

Similarly, in Re Watson and Commissioner of Taxation[89] relief was refused to an applicant with a poor compliance history evidenced by his failure to lodge his income tax returns and BASs by the required date for numerous periods.

Illegally accessing superannuation benefits will also count against release. In Moriarty, the applicant had illegally accessed his superannuation benefits in the income years 2007 and 2008, accessing $16,497 and $147,600 respectively.[90] The AAT observed that the applicant ‘accessed these funds apparently without thought to his outstanding taxation lodgements and subsequent liabilities that would arise’.[91]

We contend that some care should be taken by decision-makers in using a poor tax compliance history against an applicant and that it is important to understand the reasons behind the compliance history, which are often the cause of the hardship itself. Later in this article we contend that a new approach is needed to distinguish better between different levels of moral culpability.

3 Availability of Payment Arrangements with the Commissioner

Relief may be refused on discretionary grounds if entering into a payment arrangement with the Commissioner is realistically open as an alternative. Such was the case in Lipton and Commissioner of Taxation,[92] where the applicant husband and wife owed $23,116 and $1,885 in primary tax respectively. On the evidence, the applicants had an excess of income over outgoings of approximately $1,520 per fortnight available to them such that, according to the AAT, they could enter into appropriate payment arrangements with the Commissioner, who had previously indicated his willingness to do so.[93]

A similar issue arose in Thomas.[94] The applicant had requested the Commissioner to release him from payment of tax amounting to $64,047. Based on a number of assumptions, the AAT found that the applicant’s income exceeded his expenditure by almost $3,500 each month. However, his liabilities exceeded his assets such that he clearly could not meet his debts from his assets.[95] The AAT considered that the applicant could explore whether the option of payment to creditors, including the ATO, by instalments was open to him:

While that option remains open in relation to each of his creditors and while they are not pressing for payment and have not taken steps to, for example, garnishee his bank account ... he is not facing serious hardship. He can meet his day to day expenses and, by means of his savings and his income, he can make a contribution to the payment of his debts. In view of that, the criterion that must exist before the Commissioner has power to release the whole or part of the tax related liability has not arisen.[96]

Once a payment arrangement has been entered into, an applicant’s compliance with it becomes a relevant factor. In Watson,[97] the applicant had previously entered into three formal payment arrangements with the Commissioner, but had abandoned the repayment plans without any real explanation being provided either in writing or at the hearing. According to the AAT, all three plans were generous to the applicant, providing modest repayment schedules over extended periods of time. This suggested ‘a more than reasonable approach on the part of the [Commissioner] which now reflects poorly on the Applicant and his somewhat seemingly disdainful abandonment of those repayment plans’.[98]

A similar consideration arose in Power, in which the AAT observed:

[The applicant] has not made any sustained effort to clear arrears and achieve compliance. Since 2009 he has entered into three separate payment arrangements with the Tax Office. He has defaulted under two of those arrangements and cancelled the third. Since the middle of last year he has been paying $150 per fortnight but he has not been meeting current assessments.[99]

Of course, if the Commissioner makes clear that he does not propose to recover a debt from an applicant, the existence of the debt, in notional terms, cannot be said to impose serious hardship, since there is no present requirement to make payments to satisfy it.[100]

Again, absent special circumstances, it seems entirely reasonable to explore reasonable payment arrangements with the Commissioner and to have regard to the outcomes of any arrangements entered into.

4 Giving Priority to Expenditure Other Than Tax Liabilities

In Moriarty, the applicant had applied for, and was released from, taxation liabilities in an earlier year and was now applying again.[101] The Commissioner pointed out that after the applicant was granted release from his earlier tax liabilities, he borrowed funds and purchased the first of two properties for $230,000, which he later sold for $601,000. A second property was purchased for $492,000 and subsequently sold for $397,500.

The applicant contended that he and his former spouse purchased the first property using borrowed funds and that the property was sold because he could no longer afford the mortgage repayments. While there was little money left over from the sale, he was able to ‘transport’ the loan to another, less expensive property, which he later sold because he was in a ‘dire financial situation’.[102] He and his former wife did not receive any proceeds from the sale. The AAT agreed with the Commissioner’s submission that the applicant

apparently with insufficient cash or other assets to address his tax liabilities, and in the context of having recently obtained a release, gave priority to obtaining finance to purchase a property, to borrow more money to carry out improvements to that property when its value rose, and to continue his borrowing against a second property.[103]

Relief was refused.

Similarly, in KNNW and Commissioner of Taxation, the evidence disclosed ‘the acquisition of unnecessary assets and reduction of amounts owed to creditors has been put ahead of meeting tax liabilities’.[104] These included the purchase of a second car for $4,500 and its subsequent repairs of about $3,500; the purchase of a replacement television for about $3,200; and the reduction of a line of credit by $31,607. The AAT observed: ‘Such circumstances weigh heavily against exercise of any discretion.’[105]

Expenditure on overseas travel seems especially frowned upon, even to visit a dying relative. In Rasmussen,[106] the applicant’s wife had for many years been suffering from illness and he was increasingly required to care for her as well as their children. One of the consequences of caring for his wife was that the applicant had more limited time for his income-producing activities, which meant a significant reduction in his income. According to the AAT, the applicant was ‘in straightened circumstances’.[107] During this period, the applicant had taken an overseas holiday with his family to visit his dying sister. This was a factor that counted against him in the exercise of the AAT’s discretion:

[The applicant] acknowledged that he chose to take the family to visit his dying sister in Denmark in 2009 at a time when he had an outstanding tax liability. It might seem harsh to describe this as a choice that he made to prefer his family above meeting his tax liability. Taken in isolation, his need to visit his sister is entirely understandable. His going to visit her would have been entirely understandable even in straitened financial circumstances. His decision to take his whole family at a time when he was not able to meet his tax liability represents a clear choice to place his family above his obligation to the Australian community to pay his tax liability. His choice is a matter for him entirely but it is a matter that does not favour the exercise of a discretion releasing him from paying a tax liability he chose to put to one side in making his personal decisions.[108]

Previous levels of expenditure by the applicant must also be seen as reasonable, as distinct from current levels of expenditure which is assessed as part of the income and outgoings test. In KNNW,[109] the applicant had outstanding tax liabilities of approximately $26,045, which was the balance owing after an application for release was allowed in part, to the extent of $70,000. There was some debate about the appropriateness of the applicant’s expenditure and projected expenditure, which, after he became aware of his tax debts, included: annual holidays away from the capital city; children’s sporting competitions and music lessons; regular, but modestly priced alcohol for personal consumption; gifts for family and friends; two cars available for family use; an 18th birthday celebration; interstate travel for one of the children to visit a friend; and a replacement television for about $3,200. The applicant contended that all of his family’s expenditures were not discretionary by ordinary community standards. The AAT disagreed:

With the exception of the television and possibly the second car, all of these expenditures are probably best characterised as discretionary but not extravagant expenditures of a family living a comfortable middle class life style in a comfortable middle class suburb of an Australian capital city.

The television is probably best characterised as something above ‘not extravagant’ as there are many models of television receivers that could be acquired for much less than $3,200.

A second car, even one that costs $8,000, is something that is also best characterised as a little above ‘not extravagant’.

There are probably many in the community who cannot afford a lifestyle that includes spending money on the items listed above who do not receive government assistance and concessions.[110]

The AAT concluded:

Where there has been ... maintenance of a lifestyle that can be seen as enjoying the comforts of middle class Australian life with a degree of discretionary, albeit not all extravagant, expenditure, the correct and preferable conclusion is that a relieving discretion ought not be exercised.[111]

5 Giving Priority to Creditors over the Commissioner

Giving priority to creditors over the Commissioner weighs against applicants in a manner similar to giving priority to expenditure other than tax liabilities. In Rasmussen, the applicant had made payments in respect of the family’s two assets. Deputy President Forgie stated that

when choosing to maintain payments on privately acquired assets but not to maintain any payments to meet a tax liability, a taxpayer is saying that the community should support him or her for his or her share of the costs of meeting the infrastructure and services that are met out of taxpayers’ meeting their tax liabilities.[112]

The notion of giving priority to creditors over the Commissioner extends to the payment of credit cards. In Watson,[113] the applicant’s taxation debt related to his self-assessed income tax liabilities between 2008 and 2012, according to which he owed $52,109. The Commissioner conceded that the applicant would suffer serious financial hardship if the tax liabilities in question were to be satisfied. However, one of the factors that weighed against the exercise of the discretion was that he had made six payments in 2013 in respect of credit cards, together with some bank liabilities.[114] Cox and Commissioner of Taxation is the first case to have been decided in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.[115] In this case, the AAT found that an applicant refinancing a property to save his home was not unreasonable, nor would he have been expected to access those funds to pay his taxation liabilities or accept a deferral of mortgage repayments as part of the COVID-19 relief offered by his lender.[116]

Accordingly, we contend that some care should be taken by decision-makers in making judgements about applicants who ‘prioritise’ certain expenditures or creditors over tax liabilities. Such expenditures might be a reaction to the causes of hardship itself rather than a deliberate attempt to defeat the Commissioner, and it is again important to distinguish between different levels of moral culpability.

6 Possible Bankruptcy of the Applicant

The possible bankruptcy of an applicant if an application for relief is refused does not, of itself, constitute serious hardship. The issue was discussed in Corlette v Mackenzie,[117] where the applicant had contended that he was a chartered accountant and that bankruptcy might jeopardise his ability to work. Einfeld J concluded that there was no evidence that bankruptcy would prevent him from working in that capacity even if it prevented him from owning his own practice.[118]

7 Inheritances

A future inheritance is unlikely to count as an asset, however, the likelihood of receiving an inheritance has been taken into account as a discretionary factor in refusing release. In Lipton, the applicant wife’s mother had passed away some two years before the hearing.[119] Under cross-examination, the applicant agreed that she would inherit approximately $200,000 from her mother’s estate. The AAT noted that it would not be appropriate to grant discretionary relief in those circumstances.[120]

8 The Misfortune is of the Applicant’s Own Making

The AAT has occasionally stated that the discretion ought to be refused if the misfortune is of an applicant’s own making. In Watson,[121] for example, the AAT took the view that any hardship that the applicant would experience was largely of his own making, and not the result of a misfortune beyond his control. The applicant had at times earned in excess of $4,000 a week, which supported a finding that he was at those times in a position to pay his taxation debts as and when they fell due, but elected not to do so.[122]

Similar language was employed in Power.[123] The AAT noted that the applicant’s outstanding tax liabilities had

been brought about by his own failure to meet his tax obligations. It is not a situation that has been forced upon him. He has simply failed to give proper priority to paying his tax. Since entering the PAYG instalment system in 2008 he has paid only four of 22 assessments.[124]

It is doubtful whether an applicant’s misfortune, which is or is not of their own making, is an independent factor that counts against them. It might perhaps be more accurate to say of the applicant in Watson that he gave priority to expenditure other than his tax liabilities, and of the applicant in Power that he had a poor tax compliance history.

It is a daunting task for an applicant to litigate an adverse decision of the Commissioner on a serious hardship application. We have examined AAT and Federal Court of Australia cases since the introduction of the serious hardship relief provisions in 1915.

An overview of decisions across tribunals and courts over the past 50 years is provided in the Appendix to this article. Specifically, the Appendix includes for each case: the total tax liability involved with a breakdown for tax liability, interest and penalties; both positive and negative factors involved in the decision-making process of the tribunals and courts; and the outcome.

Of the 34 cases decided in the past 50 years, all but four found in favour of the Commissioner. These four cases were A Taxpayer,[125] Commissioner of Taxation v Milne,[126] GSJW and Commissioner of Taxation,[127] and Cox.[128] This is despite the majority of cases being conducted under full merits review, with only five cases decided under former s 265 of the ITAA36 when only a judicial review was available.

Of the four cases where relief was granted, only Milne and Cox resulted in a full release from liability. In Milne, the taxpayer was able to establish both serious hardship, and the fact that said hardship arose from misfortune for which the taxpayer was not responsible.[129] In Cox, the taxpayer was granted full release of the eligible portion of his taxation liabilities (with the ineligible portion comprising GST debts and penalties for failure to lodge on time). The AAT found that it would not be possible for the taxpayer to repay his full taxation debts in his lifetime without suffering substantial and long-term serious hardship, and the weight of his taxation debt was also likely to be causing some detriment to his mental health.[130]

It might reasonably be inferred that the Commissioners past and present have done a good job in their decision-making processes given nearly all decisions have been affirmed. Indeed, the majority of the applicants over the past 50 years failed at the first hurdle of the two-stage approach.[131] That is, many simply did not suffer from serious financial hardship as found by the AAT based on the facts of cases such as Re Balens and Commissioner of Taxation,[132] Huckle and Commissioner of Taxation,[133] Lipton,[134] Lau,[135] ZDCW,[136] Schweitzer,[137] GSJW,[138] among others. However, as discussed above in Part II(C), many other cases failed for the fact that the taxpayer would suffer serious financial hardship regardless of being granted relief; that is, on the second hurdle of the two-stage approach. This includes cases such as Rasmussen,[139] Thomas,[140] Re Hulsen and Commissioner of Taxation,[141] KNNW,[142] and Moriarty.[143]

Further, there are three systemic issues that do not favour applicants, quite apart from the legislative constraints discussed above in Part II.

The first systemic issue is that the applicant bears the burden of proving that the decision concerned should not have been made or should have been made differently.[144] In Rasmussen, Deputy President Forgie made the following observations about the nature of the burden and its discharge in the context of serious hardship:

The individual who carries the burden of proof in relation to this decision must produce to the Tribunal evidence on which it can be satisfied, on the balance of probabilities, of the findings of fact that are relevant, first, to the ultimate finding that a person would suffer serious hardship if required to satisfy the liability and, if so, then to the exercise of the discretion. The individual can satisfy that burden by producing evidentiary material and calling witnesses.[145]

It should be noted that for tax appeals more generally, an applicant will bear the burden of proof, which is appropriate when evidentiary matters are wholly within the knowledge of the applicant, rather than the Commissioner. However, this often creates an insurmountable task for unrepresented applicants.

It follows that the second systemic issue is the financial circumstances of applicants who are suffering financial hardship is such that most cannot afford representation. This is shown in the Appendix to this article, with self-represented taxpayers comprising the majority (that is, 64.5%) of applicants for hardship relief. They are faced with presenting a case before the AAT in which the Commissioner is invariably represented, often by legal counsel. Most will not properly understand the burden of proof and what it entails, and will not have gathered the necessary evidence. Many such cases are doomed to fail from the outset. This article presents a suggestion for associated reform in Part IV(D) below.

The third systemic issue is that over the past 50 years there are disproportionately fewer taxpayers from ‘blue-collar’ occupations seeking relief compared to ‘white-collar’ occupations. As shown in the Appendix, taxpayers in ‘white-collar’ occupations comprise the majority (that is, 65.4%) of all applicants for hardship relief and 75% of all successful applicants. This suggests that inequalities of educational opportunities and outcomes make it less likely for taxpayers suffering from structural disadvantage to pursue serious hardship relief through to the litigation stage. However, confirming a causal relationship from this finding requires further research.

In distilling AAT cases to their essential propositions, the nuances and complexities of individual cases can be lost. We therefore describe here one case more fully to capture the complexity of a case and illustrate the principles discussed above.

In Re BFCB and Commissioner of Taxation,[146] the Commissioner had issued a notice of assessment to the applicant showing a taxation liability of $70,571. The applicant partially paid the tax debt leaving the sum of $61,108 of the primary tax outstanding and $13,540 of GIC. Much of that liability had arisen from the inclusion of a net capital gain on the sale of an investment unit.

The applicant had been self-employed since 1992 and had always met her taxation liabilities. She had suffered chronic health problems, including major fatigue and depression for most of her life, although, as a self-employed person, she could match her hours of work to her physical condition. She had been a single parent since 1998 and had brought up her daughter, who was born in 1993, without child support payments.

In 2008, the applicant was diagnosed as suffering from breast cancer. In January 2013, she lost her major business client with the result that she no longer had a reliable source of income and used all of her financial resources, including credit cards, to support her daughter and herself. She was unable to borrow further from the Bank of Melbourne, which was the mortgagee of her home, or on her credit cards, and had not been able to find work whether as a self-employed management consultant or as an employee.

In February 2013, the applicant decided to sell her home and her investment unit ‘to sort out ... [her] finances’.[147] It was the sale of the investment unit that had given rise to the net capital gain.

In August 2013, she purchased a house to live in for $630,000, relying on a loan of $350,000 from the Bank of Melbourne. She was required to make a minimum repayment of $615 on the mortgage each fortnight. She also purchased a 1999 Subaru Liberty Sedan, which she valued at $2,500, and separately retained for her daughters’ use a 1999 Ford Fairmont, which she had purchased in 2005 and which she also valued at $2,500.

In January 2015, the applicant approached Anglicare, which assisted her in exploring options to resolve her financial problems and, in the meantime, she continued to meet only those of her financial commitments relating to her accommodation, health and food. In December 2014, she applied to Centrelink for benefits, but had, until then, relied on her savings.

On 26 May 2015, the applicant’s doctor certified that the applicant had numerous, chronic health issues including a history of cancer. These all contributed to excessive fatigue, which affected her daily physical and cognitive functioning.

At the date of the hearing, the applicant’s daughter was 23 years of age and a full-time tertiary student in Melbourne but then studying in France on a scholarship for another month or so. The applicant received a pension of $250 per fortnight paid by the Irish Government and, from the beginning of 2015, a social security payment of $250 per fortnight from Centrelink. The applicant had been working since August 2016 for about 20 hours each week earning just under $24 per hour.

On the evidence, the applicant was well short of meeting her day-to-day living expenses, and that was so whether she owed the tax liability or not. If the house were sold for $650,000, she would have a surplus of $217,000 once her debts, other than the tax liability, were paid. Only then would she have enough remaining to pay her tax liability.

At the hearing in the AAT, the applicant was unrepresented and appeared in person while the Commissioner was represented by counsel. The AAT found against the applicant and denied relief.

One can always debate the exercise of a discretion, but, with respect to the AAT, greater emphasis appeared to be placed on the ‘negative’ factors over the ‘positive’ factors in the weighing process.

It is worth synthesising some of the positive factors. The applicant had met her taxation liabilities for many years. She was a single parent and had brought up her daughter without child support payments. When she no longer had a reliable source of income, she used all of her financial resources, including credit cards, to support her daughter and herself, rather than relying upon welfare. She sold her home and investment unit to sort out her finances. She then approached Anglicare, which assisted her in exploring options to resolve her financial problems. In the meantime, she continued to meet only those of her financial commitments relating to her accommodation, health and food. Only later did she apply to Centrelink for benefits.

All of the above was done despite her personal circumstances, in particular, that she had suffered chronic health problems, including major fatigue and depression, for most of her life, and the diagnosis that she was suffering from breast cancer. These had all contributed to excessive fatigue which affected her daily physical and cognitive functioning.

Against this background, any ‘negative’ factors should bear some scrutiny. There was essentially one, that in August 2013 she purchased a house and a second car. The house was purchased for $630,000, with a mortgage of $350,000, and the car was valued at $2,500.

As to the house, it will be recalled that just a few months earlier, in February 2013, she had sold her home and her investment unit to sort out her finances. In that circumstance, it seems understandable that she might have purchased a more modest home to live in. It was the sale of the investment unit that had given rise to the net capital gain. At that time, she was aware that there would be a capital gains tax (‘CGT’) liability, but was later ‘shocked’ to learn of its magnitude. It may not have been wise to commit to a mortgage when her income had fallen, but the bank was obviously prepared to lend and she needed a place to live.

As to the car, the purchase in 2013 of a 1999 Subaru Liberty Sedan, valued at $2,500, could not be viewed as extravagant and, again, the size of the CGT liability was not then known.

With all due respect to the AAT, it is difficult to see how the one negative factor could have outweighed the positive factors in the exercise of the discretion, unless it is viewed as a disqualifying factor. We suggest in Part IV(B) below a different approach that might be taken to exercising the discretion.

This section makes four recommendations to modernise the current law and policy design given the legislative constraints identified in Part II and the systemic issues identified in Part III. It is hoped that these recommendations will assist policymakers in improving the operation of the serious hardship provisions. The recommendations are:

• The amendment of the causal relationship requirement;

• The implementation of a sliding scale for negative discretionary factors;

• The expansion of serious hardship relief to other taxation liabilities (including GST) and other entities; and,

• Improving access to free and (where possible) independent tax advice across the dispute resolution lifecycle.

Each recommendation is detailed below.

The proposition that there must be a causal relationship between the requirement to satisfy the tax liability and the serious hardship is open to doubt. As detailed above in Part II(D), this article outlines multiple reasons why this proposition is unsound. One of these reasons is the emerging empirical evidence that tax debts are often a sub-component of overall debts for financially vulnerable people.[148] Refusing relief on the basis that the applicant would still suffer serious hardship due to their other financial commitments is disconnected from the realities of financial vulnerability for many taxpayers in modern-day Australia. This issue is especially timely and topical considering the economic aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic.[149]

Accordingly, we respectfully suggest that this area of the law be clarified so that the phrase ‘serious hardship’ returns to its ‘all embracing’ meaning.[150]

The policy rationale supporting the existing regime is that, if relief were granted, other creditors would benefit over the Commissioner. To overcome the notion that other creditors might benefit, consideration should be given to inserting a provision that permits the Commissioner, in the event of an applicant’s bankruptcy within, say, five years of release, to prove as a debt in the bankruptcy the amount released to the taxpayer. This proposed legislative mechanism would ensure the Commissioner is not disadvantaged by releasing the taxpayer from the debt, which would automatically be deemed provable as a debt in circumstances involving voluntary administration, liquidation or bankruptcy, but not otherwise.

Consideration should also be given to permitting the Commissioner to meet with other creditors before any administration, liquidation or bankruptcy. The Commissioner is currently constrained by the ‘secrecy’ provisions of the taxation laws found in div 355 of sch 1 to the TAA. These provisions essentially prevent the disclosure of information about the tax affairs of taxpayers except in certain specified circumstances, and it is an offence for taxation officers to make such a disclosure.[151] Significantly, it is not a defence to a prosecution of a taxation officer if the taxpayer has consented to the disclosure.[152] We suggest the secrecy provisions be amended to permit disclosure to creditors for the purpose of reaching agreement on releasing the taxpayer from debts, including taxation debts, but only in relation to a serious hardship application and with the written consent of the taxpayer.

Further analysis and research is needed in this area, especially to avoid any unintended outcomes in changing insolvency and secrecy laws. It would be important, for example, to ensure that vulnerable taxpayers were not effectively denied credit on future occasions or felt improperly pressured to give consent about disclosure of their financial affairs.

The Inspector-General of Taxation (‘IGoT’) is currently investigating undisputed tax debts in Australia.[153] These debts have increased significantly in the 2019–20 tax year.[154] While the IGoT’s review is focused on identifying the segments of the economy experiencing increases in undisputed debt collections, it would be meaningful to also explore the underlying drivers for these debts. For example, if no such analysis has already been conducted internally by the ATO, it would also be useful to determine indicators of potential recovery of debts, and determine relative success rates of payment plans by taxpayer cohorts to then target debt collection more strategically given the ATO’s limited resources.

This article highlights the range of factors taken into account in the exercise of the discretion. Too often these factors seem like de facto disqualifying factors — as demonstrated in cases such as BFCB.[155] It weighs heavily against an applicant, for example, that they have paid other creditors in preference to the Commissioner. This includes, in practice, cases where a taxpayer in financial hardship pays off the credit card in preference to the taxation liability. This is likely to happen because the credit card is needed to purchase life’s essentials. It is difficult to see why this should necessarily be a de facto disqualifying factor.

The existing approach fails to distinguish between different levels of moral culpability for failure to pay tax. This article suggests that legislative reform is needed to clarify that a failure to take reasonable care (in paying off credit cards before tax, for example) is not a disqualifying factor, while deliberate attempts to evade the payment of tax debts would be a disqualifying factor. Accordingly, an applicant might intentionally pay off a credit card before tax, but is not thereby seeking to intentionally disregard any taxation obligations.

These degrees of culpability would distinguish between the taxpayer who in difficult times failed to lodge several tax returns (and thus failed to take reasonable care) and the taxpayer who deliberately and intentionally disregarded their obligations (such as the senior barrister who fails to pay tax over many years).

A complementary benefit of a ‘sliding scale’ approach would be to codify in the serious hardship relief provisions the ATO’s existing compliance model (Figure 1). As noted in Part I, this model makes a clear distinction between taxpayers who are non-compliant due to various mitigating circumstances as opposed to taxpayers who deliberately decide to be non-compliant, and is responsive to this nuance.

Considerations that can assist in guiding the operation of a sliding scale already exist in the case law. For example, as outlined in Re David and Commissioner of Taxation, the seven criteria relevant to the proper exercise of the discretion are:

• the circumstances out of which the hardship arose;

• whether those circumstances could have been foreseen and controlled by the applicant;

• whether the applicant has overcommitted themselves financially;

• whether the applicant or dependants had suffered any serious illness or accident involving irrevocable financial loss to the applicant;

• whether the applicant has been in regular employment;

• whether the circumstances of hardship are likely to be of a temporary or recurring nature; and

• whether a decision to remit the debt would place the applicant in a preferred position to other taxpayers.[156]

Further, a sliding scale approach would also be in the public interest, which is an element of relevance in the exercise of the discretion. As noted by Stone J in

A Taxpayer, ‘[the public interest] is relevant for the Commissioner or, in this case the AAT, to consider how the goal of collecting public revenue would best be served.’[157]

As noted in Part II(B), not all types of tax liability are eligible for release. Section 340-10 of sch 1 to the TAA applies only to income tax, FBT (including instalments), Medicare levy, PAYG instalments, and related GIC and penalties.

One notable exclusion, as mentioned previously, is GST. For example, more than half of the applicant’s tax liabilities in Burns[158] related to GST, but these liabilities were not eligible for release. At present, businesses experiencing serious financial hardship can request priority processing of their BAS,[159] but this is very different to them being granted relief in relation to unpaid GST liabilities.

The existing policy justification for the exclusion of GST is likely that this type of tax is an indirect tax, the economic burden of which is generally not intended to be borne by the ‘taxpayer’; but is intended to be passed on to the final consumer.[160] In this way, the taxpayer effectively acts as an unpaid agent of the Commissioner in collecting the tax.

This is out of step with the modern composition of the workforce. Specifically, the past few decades have seen the emergence of non-traditional forms of work including engagement of independent contractors as hiring options for employers.[161] So, rather than exclusively operating with the personal income tax system, these independent contractors may select other structures for conducting their business, such as corporate or trust entities.[162]

Accordingly, this article proposes the legislation be amended to expand the scope of serious hardship relief to other taxation liabilities (including GST) and to all small businesses (whether operating as sole traders or through corporate or trust entities).

Even before the COVID-19 crisis, small businesses accounted for around 60% of total collectable debt.[163] The initial six-month period of managing the economic aftershocks of the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia was marked by the introduction of an array of temporary relief measures recommended by government or mandated by state and federal parliaments, including the freezing of Australian Government debt recovery action[164] and bank loan repayment deferrals.[165] The next phase involves the reduction and removal of these measures. Commentators from industry,[166] the community sector[167] and academia[168] have observed that this is likely to result in a ‘financial cliff’. With the ATO gradually recommencing debt collection action,[169] pre-existing tensions and sources of dissatisfaction[170] between small businesses and the ATO are likely to resurface.[171]

While the ATO’s Tax Help Program currently exists, it is limited in scope and duration, and is run by volunteers rather than tax professionals.[172] Further, the ATO’s Dispute Assist Service is available to unrepresented individuals and small businesses to provide assistance with any dispute resolution issues, mediation or conciliation — but these services, under the regulatory system, can neither provide tax advice nor can they represent individuals.

Emerging research indicates that there currently exists a lack of access to tax justice across all stages of the tax dispute resolution lifecycle in Australia.[173] Specifically, Kayis-Kumar, Walpole and Mackenzie found that financial counsellors believe that free and independent tax advice is needed particularly for debt/hardship discussions for individuals and small businesses located in communities with relatively higher levels of socio-economic disadvantage.[174]

Consideration should be given to funding applicants in AAT proceedings who would otherwise be self-represented, except perhaps in the most egregious of cases. This is particularly important since the situations faced by those in financial hardship are disproportionately burdensome given the legal obligation to comply with the incredibly complex Australian tax and transfer system.[175]

A further benefit is that funding representation would reduce the burden on the already scarce resources of the AAT and might result in better outcomes. This is particularly important because tax law is not conceptualised as a specialist service by Legal Aid.[176] Despite the absence of a platform for legal help in relation to tax law, small businesses are given dispute resolution support through the Australian Small Business and Family Enterprise Ombudsman’s (‘ASBFEO’) ‘Small Business Concierge Service’.[177] This service helps taxpayers decide if an application to the AAT for review of an ATO decision is an appropriate pathway to resolution. In conjunction with the new Small Business Taxation Division of the AAT, the Small Business Concierge Service provides targeted support to small businesses in dispute with the ATO.

For example, one of the authors has represented an applicant for relief through funding provided by ASBFEO. After a consideration of the law and evidence, the applicant was advised to abandon the AAT proceedings (saving considerable expense for both the AAT and the Commissioner) and enter into a payment plan with the ATO. This seemed to achieve a better result for both the applicant and the Commissioner, and at a much lower overall cost.

Further, as noted above in Part IV(C), the advent of both the casualisation of the workforce and the gig economy gives rise to unintended consequences for low-income taxpayers who are increasingly conceptualised as earning business income. This disqualifies them from accessing the ATO’s Tax Help Program. Accordingly, expansion of the criteria for access to the ATO’s Tax Help Program to include independent contractors (including sole traders) would likely provide more accessible tax services and greater engagement with the ATO, while also bolstering tax literacy and improving tax morale.[178] This would likely assist the ATO’s mission of fostering a culture of voluntary compliance in the medium-term, and may contribute to reduced instances of tax debts arising from small business compliance obligations (including BAS) in the longer-term.

For over 100 years there has been a discretion in taxation legislation to release taxpayers from tax-related liabilities on the ground they would suffer serious hardship. Despite its long history, there is a relative dearth of literature both on the serious hardship relief provisions in Australia and relevant cases brought to a tribunal or court hearing. Other aspects of tax administration have evolved in the past two decades, including the ATO’s focus on mitigating reputational harm arising from community perceptions of its debt collection practices.

This article detailed the legislative background and regulatory landscape in relation to these provisions, including exploring the meaning of ‘serious hardship’, outlining the administrative guidance and detailing the eight discretionary factors that have often received prominence in AAT decisions.

In doing so, this article identified four problematic aspects of the existing regime and makes recommendations for reform.

First, there should be an amendment to the requirement that serious hardship relief can be granted only in instances where said hardship is predicated by the tax liability. This requirement is disconnected from the realities of financial vulnerability for many taxpayers, given tax debts are often a sub-component of overall debts.

Second, the existing regime fails to distinguish between different levels of moral culpability. This article recommends the introduction of a sliding scale for negative discretionary factors. This provides relief for those who have generally participated in the tax system, but dropped out due to health or other shocks.

Third, this article proposes the legislation be amended to allow serious hardship relief for other taxation liabilities (including GST) and for small businesses (whether operating as sole traders or through corporate or trust entities). This reform would modernise this element of the tax law to reflect the shifting parameters of the labour market (including the increasing use of Australian Business Numbers among taxpayers in precarious employment).

Fourth, there is a pressing need for greater access to free and independent tax advice across the dispute resolution lifecycle. This is particularly important in the context of debt and hardship discussions for individuals and small businesses located in communities with relatively higher levels of socio-economic disadvantage.

These four recommendations are designed to modernise the current policy and law design of the serious hardship relief provisions and, in doing so, result in better outcomes for financially vulnerable individuals and small businesses, while also maintaining trust and confidence in the ATO among the wider community.

|

Tax liability

|

Positive factors

|

Negative factors

|

Relief granted?

|

Self-represented?

|

Professional background

|

|

|

Section 64(1) of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1915

(Cth)

|

|

|

||||

|

N/A

|

|

|

||||

|

Section 97 of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1922 (Cth)

|

|

|

||||

|

N/A

|

|

|

||||

|

Section 265 of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (Cth)

|

|

|

||||

|

Hissink v Taxation Relief Board

|

unknown

|

unknown

|

unknown

|

No

|

Yes

|

Medical practitioner

|

|

Powell v Evreniades

|

$175,183

|

• Physical injury

(car accident).

• Family difficulties

(with daughter).

• Dependent children.

|

• Sufficient equity (estate).

• Sufficient cash ($12,000).

• Large discretionary spending.

• Can reduce weekly outlays (mortgage).

• Receive benefits and subsidies (work compensation & rental

assistance).

|

No:

Remitted for reconsideration

|

No

|

Not specified

|

|

Van Grieken v Veilands

|

$19,660

|

unknown

|

• Significant equity.

• Prioritising non-tax debts.

• Excess income over expenditure.