Sydney Law Review

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Sydney Law Review |

|

Communicative Justice and COVID-19: Australia’s Pandemic Response and International Guidance

Alexandra Grey[*]

Abstract

This article is driven by concerns over communicative justice and the author’s earlier research finding that only a patchy framework of laws and policies guides decision-making for Australian governments’ multilingual public communications. The article investigates the additional guiding role of international law, specifically the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and recent commentary by international organisations, alongside an original, empirical case study of Australian governments’ COVID-19 communications. In analysing the Australian case study in light of the international guidance, the article concludes that although Australian COVID-19 communications were available in a relatively high number of languages, they were characterised by inefficiencies and limited community input or strategic planning, leaving Australia arguably falling short of progressively realising its right-to-health obligations.

Please cite this article as:

Alexandra Grey, ‘Communicative Justice and COVID-19: Australia’s Pandemic Response and International Guidance’ (2023) 45(1) Sydney Law Review 1.

![]()

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Licence (CC BY-ND 4.0).

As an open access journal, unmodified content is free to use with proper attribution. Please email sydneylawreview@sydney.edu.au for permission and/or queries.

© 2023 Sydney Law Review and author. ISSN: 1444–9528

This article constitutes a practically oriented synthesis of empirical Australian data and rarely overlapping linguistic, legal and health sciences scholarship. A ‘communicative justice’ frame directs this research to draw on knowledge from across disciplines in order to solve real problems through inquiry into their social contexts. In response to health inequalities, communicative justice scholar and anthropologist Charles Briggs draws together disparate fields of scholarship, pursuing ‘communicative justice in health [by] seeing how health inequities are entangled with health/communicative inequities’.[1] Such a frame highlights that communications about healthcare have differential impacts and that these differences contribute to injustices in access to healthcare and health outcomes. This article develops that idea, using an Australian case study to explain that greater communicative justice could, and should, be achieved through the interaction of international law’s specific language rights and health rights. This article seeks to promote positive change in Australia’s law and policy framework about multilingual health communications, and in the resulting communications practices, by highlighting useful guiding commentary from international bodies in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and about the international right-to-health obligations held by Australia.

Concerns about multilingual crisis communications have been commonplace throughout the COVID-19 pandemic.[2] The pandemic brought an acute dimension to a pre-existing problem with the public communications that Australian state and federal governments provide to a public that is linguistically diverse. Although multilingual government communications exist — ‘more than 1500 resources addressing public health information had been produced in almost 60 languages’ by the New South Wales (‘NSW’) government alone during the first 18 months of the pandemic[3] — there have been reasons to doubt whether Australian governments’ communications reached non-English-dominant audiences. For instance, it was reported that some communications in languages other than English (‘LOTEs’) were not kept up to date,[4] were poorly translated[5] and lacked key information,[6] and that intended audiences may not have known that government information in LOTEs was there to be found.[7] These were problems before the COVID-19 pandemic, too. Australia’s Chief Scientist reported that a 2011

review of Australia’s public health response to the H1N1 pandemic found a need for ‘consistent approaches to engaging with high-risk communities’ including Indigenous people and those from non-English-speaking backgrounds’ ...[8]

My and Alyssa Severin’s 2019–20 study of NSW government web-based communications (‘NSW study’) also highlighted inconsistency in engaging with people who have non-English-speaking backgrounds.[9] Another problem is the belief, held by some leaders, that multilingual public pandemic communications are not a government responsibility, a view exemplified by a NSW Police deputy commissioner’s statement in 2021 that it is incumbent upon families and friends to explain COVID-19 rules to non-English speaking people.[10]

Problems with governments’ multilingual public health communications are not unique to Australia; nor are the health inequalities that communicative injustices exacerbate. Researchers overseas have noted:

Multilingual crisis communication has emerged as a global challenge during the COVID-19 pandemic. Global public health communication is characterized by the large-scale exclusion of linguistic minorities from timely high-quality information.[11]

Thus, stories of language barriers to information during the pandemic emerged worldwide, as well as stories of community organisations initiating efforts to overcome communication hurdles,[12] and of effortful government responses.[13] (Australian efforts to improve are detailed in Part III.) Further, the experience of the pandemic around the world indicates that when people cannot access reliable government information, they often turn to social media for information from non-government sources, including both true information ill-suited to their local circumstances and false information.[14] This has been described by the Director-General of the World Health Organization (‘WHO’) as an ‘infodemic’ running alongside the pandemic.[15]

Moreover, and beyond the COVID-19 context, diverse sources indicate that differential health outcomes correlate to the language of public health communications. In general, ‘[p]opulation studies in Australia and worldwide ... show that ... [l]ow health literacy [is] more common in older adults, among those from a non-English speaking background ... and can be further reduced under high stress’.[16] This is not to claim that language is the only determinant in unequal COVID-19 outcomes. Rather, not speaking the dominant language intersects with being not from the dominant race, lower socio-economic status, social exclusion and less safe workplaces. Those are recognised internationally as key social determinants of ill-health generally[17] and of comparatively worse COVID-19 infection and fatality rates specifically.[18] Differential COVID-19 outcomes can therefore be understood as highlighting linguistic exclusion as one dimension of the social determinants of ill-health.

While large studies on differential health outcomes of COVID-19 were limited at the time of writing,[19] smaller studies and respectable media sources indicated that being from a non-English speaking background was linked to low COVID-19 physical and mental health outcomes in Australia. To illustrate, the Victorian government came under fire throughout 2020 for not engaging with ‘multicultural communities, who were disproportionately affected with the virus during the deadly second wave’[20] and when a ‘hard lockdown’ (that is, no leaving home) was abruptly imposed on nine towers of public housing in Melbourne in July 2020, it was enforced with a strong police presence but with delays in interpreting and translating information to the towers’ many non-English-dominant asylum seeker and refugee residents. This reportedly increased their trauma, distress, confusion and distrust.[21]

Further, the established knowledge from crisis studies is that crises can both exacerbate and be exacerbated by pre-existing vulnerabilities — including linguistic vulnerabilities — and that this causes a ‘cascade’ of unequal impacts.[22] This is a useful way to conceive of the COVID-19 pandemic’s longevity and its unjustly varied impacts. A prescient early-2020 work by leading crisis translation scholars ‘considers language barriers in the context of multi-dimensional cascading effects that widen existing vulnerabilities or engender new ones by means of miscommunication’.[23] Similarly, another has noted:

Linguistic minorities are typically considered more vulnerable than the general population partly because of language barriers and structural inequality, but, when compared to other socially vulnerable groups such as women, children, and the elderly, this particular group has been under-investigated.[24]

These concerns spurred my inquiry into the law and policy framework for multilingual, public pandemic communications in Australia, and whether that framework, not only the communications themselves, could be improved. There was little existing research, but the answer indicated by the research which did exist was that the framework at the national and state levels did not offer much guidance. Shortly before the COVID-19 pandemic, Severin and I audited the law and policy framework underpinning multilingual public government communications in NSW, reviewing the sparse existing literature and adding empirical research.[25] We identified 91 Acts containing the term ‘English’ and/or ‘language’ which we then analysed, along with formal and publicly available policies affecting language and public communications. Our study found a dearth of either legislation or policy. We also identified shortfalls in the rules and policies that did exist, including the ambiguous role of NSW’s statutory multicultural principle about linguistic diversity; haphazard legislative requirements for ‘plain’, ‘simple’ and/or ‘understood’ language; and a lack of accountability mechanisms for non-compliance. We therefore warned that relying on informal and post-hoc departmental policies for the decision-making and production of multilingual public communications was unsuited to equitably fulfilling the needs of all NSW constituents. Such issues were foreshadowed overseas in research revealing a contraction in multilingualism on Norwegian government websites when ‘pressure towards homogenization’ becomes the (perverse) response to increased diversity.[26]

The COVID-19 pandemic then presented another reason and another opportunity to investigate public communications practices and the frameworks behind them. I therefore undertook the Australian case study reported here in Part III. The data was also published within a submission to a parliamentary inquiry in 2020,[27] but this is its first scholarly publication, and here the data is contextualised within media reports on pandemic communications up to early 2022, and analysed anew. Specifically, the empirical findings are analysed in Part IV in relation to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (‘ICESCR’),[28] to which Australia is a signatory, and related recent commentary from international organisations. The ICESCR includes a right to non-discrimination on the basis of language (‘linguistic non-discrimination’) and rights to health.

As a state party, Australia has an obligation to continually work to improve its realisation of economic, social and cultural (‘ESC’) rights; this means Australia should take stock of the international commentary responding to the COVID-19 pandemic, with which this article helps. The article’s review and identification of emergent shared expectations is presented as a useful recapitulation for other researchers as well as being central to this article’s suggestions for improving Australia’s public health communications.

The commentary I reviewed comprises publications from international organisations which are influential but not binding in international law, including the following:

• general comments from the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (‘CESCR’) (that is, interpretative statements on articles of the ICESCR);[29]

• reports by special rapporteurs; and

• guidelines, plans and reports from international officeholders and organisations, including the WHO, the Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness and Response (‘Independent Panel’), and the Council of Europe’s Committee of Experts of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages (‘Committee of Experts’).

This commentary is not binding but is accorded weight — particularly the CESCR’s comments — in determining what progressive realisation of ICESCR rights entails. I also reviewed less-influential commentary, including scholarship and international organisations’ press releases.

Australia’s relevant ICESCR obligations are introduced in Part II, along with an explanation of multilingualism in Australia. Australia’s position is that it is compliant with the ICESCR,[30] and its Ambassador to the United Nations (‘UN’) recently told the Human Rights Council that ‘governments must ensure COVID-19 response measures comply with international human rights obligations’.[31] After examining the empirical case study, however, this article concludes in Part V that Australia is arguably not compliant in its realisation of linguistic non-discrimination in the progressive realisation of the right to health, and that the international commentary is instructive about that progressive realisation. That is, there have been communicative injustices in Australia during the pandemic; these should be ameliorated given Australia’s ICESCR obligations; and they could be ameliorated by heeding the international guidance. The article ends by identifying outstanding questions to be pursued to develop the emerging body of communicative justice literature, and the need for governments themselves to partner in such research.

Australia has obligations under art 12 of the ICESCR in relation to the progressive realisation of the right to health and healthcare which include providing public information about health issues. Right-to-health obligations are obviously important in the context of a pandemic. The issue of multilingual health communications is pressing because the obligation under art 2 of the ICESCR regarding non-discrimination in the enjoyment of ICESCR rights is immediate, not progressive. Unlike the progressive realisation obligations imposed on states by most of the ICESCR, art 2(2) ‘imposes various obligations which are of immediate effect’ including ‘the “undertaking to guarantee” that relevant rights “will be exercised without discrimination”’.[32] Article 2(2) expressly names ‘language’ as an unlawful ground of discrimination. This provision has a ‘dynamic relationship’ with art 12 of the ICESCR on the right to health.[33] We can say in summary that the ICESCR provides a right to linguistic non-discrimination in the enjoyment of the right to health.[34]

It is not in question that ‘States Parties to the ICESCR are obliged to take whatever steps are necessary to ensure that the substantive obligations they assume under the [Covenant] are carried out’.[35] Moreover, the Special Rapporteur on Health has recently reinforced that states are compelled to keep examining the adequacy of non-discriminatory access to information and care, that discrimination is often intersectional, and that it requires structural and systemic redress.[36] Thus, Australia cannot ‘set and forget’ in satisfying its ICESCR obligations; rather, the ICESCR imposes on Australia an ongoing ‘obligation to move as expeditiously and effectively as possible towards’ the full realisation of the art 12 health rights.[37] Because of the immediacy of the art 2(2) obligation to avoid discrimination on the basis of language, linguistic non-discrimination should be a feature of Australia’s steps towards fuller realisation of the right to health.

Yet progressive realisation invokes a question of proportionality; the ICESCR undertaking of states parties is to take steps using ‘all appropriate means’.[38] For example, the degree of use of a minority language in education is held to the progressive but proportional standard of being ‘reasonable and justified’.[39] There has been relatively little guidance on what is proportionate for states in meeting the information/communication obligations that form part of the right to health, and there is no international case being brought which would clarify the standard for pandemic communications realising ICESCR obligations, to my knowledge. This under-examination may be due to common but misplaced assumptions that social rights are non-justiciable. Nevertheless, international commentary has noted that there are interacting ICESCR rights to linguistic non-discrimination in access to health and healthcare since (at least) the 2012 Report of the Independent Expert on Minority Issues, which declared that public health information ‘should be available in minority languages’.[40] More recently, but before this pandemic, international law scholar Jacqueline Mowbray expanded the argument that the prohibition on linguistic discrimination in art 2(1) interacts with the right to health in art 12 to require states to provide translations from their dominant/majority language so that linguistic minorities can access health services.[41] But key questions remain. These include whether it is proportionate for a government to exclude the languages of smaller communities in order to afford public health communications in more widely used languages, and questions as to the quality of multilingual communications. The COVID-19 pandemic has prompted development of some answers, in terms of both state practice and normative international commentary. However, without new international jurisprudence evaluating that new commentary a standard has not crystallised. That commentary is distilled in Part IV below because the progressive realisation of Australia’s ICESCR obligations requires us to keep re-assessing how non-discriminatory health rights are implemented here. Together, this guidance could supplement Australia’s patchy law and policy framework about multilingual public health communications and help Australia maintain its ICESCR obligations — if our governments are willing to accord it their attention.

A significant proportion of the Australian public use a LOTE as their dominant language. The Census counts these people through the proxy measure of households in which a LOTE is spoken, whether in addition to or instead of English.[42] In 2016, a LOTE was spoken in 38.2% of Greater Sydney households and 22.2% of all Australian households.[43] Australia’s most-spoken LOTEs are Mandarin and Arabic. However, most migrants speak English, even if they do not speak English at home: only a reported ‘6 per cent either speak little English or none at all’.[44] Most people moving to Australia know some English or learn it over time,[45] but they may not be able to understand complicated information in English, particularly written information. Moreover, there are new migrants who have not yet acquired much English, and some groups of migrants who will have a harder time learning English than others, regardless of their own willingness, including older people, women who mainly work in the home, and people whose workplaces do not allow for interaction in English.

Further, some languages share many features with English while others do not: the greater the linguistic divide to be bridged, the harder it typically is to learn English. For example, our two most spoken LOTEs, Mandarin and Arabic, notably use different written scripts to English, making bi-literacy harder to obtain. In addition to low- and non-English speaking migrants, there are Australian-born first language speakers of Aboriginal languages who have low English proficiency and Deaf Australians whose first or strongest language is Auslan, not English.[46] Moreover, there are Australian-born first language speakers of English with certain low proficiencies (for example, illiteracy). Thus, overall, there remain many segments of the Australian public for whom communications in English, especially written English, will be inaccessible or hard to understand, even though most people in Australia speak at least some English.

Although these segments of the Australian public with low or no English proficiency are minorities, communicating with them has been of heightened importance because of the nature of the COVID-19 crisis:

[I]ndividual outcomes have greater influence on the overall course of the COVID-19 pandemic than is the case in most other disasters ... [M]inimizing the personal risk of individuals [is] deeply intertwined with the overall risk to the community.[47]

It has therefore been extremely important for overall public safety that official, public communications about COVID-19 be disseminated even to those with no or low English proficiency. It is also a matter of equality and justice. To quote one of Australia’s leading healthcare communications researchers, from the start of the pandemic until now, an outstanding question is: ‘Are the right languages being targeted for the most vulnerable population[s]?’[48]

Yet this is an aspect of the pandemic response which has been challenging for Australia. A telling anecdote is that by early 2021, speakers of one of Australia’s most common LOTEs (itself a major world language) were still regularly calling a popular, community-run radio station that broadcasts in this language asking whether one had to pay to get a COVID-19 test.[49] The information that COVID-19 tests were free was important for encouraging people to get tested, which was crucial because the Australian strategy against COVID-19 relied on the early identification and containment of infections. Australian federal and state governments had placed translated COVID-19 fact sheets in this language on their websites, and had produced videos about COVID-19 in this language. Yet the informant’s report suggested both that a core fact about testing was not reaching a large minority language population, despite the production of government materials in LOTEs, and that people’s go-to source of information was a LOTE-medium radio station rather than an official government source. This resonates with a reported story of a Mandarin-speaking community leader who had lived in Australia for decades but had no idea that Australian governments produced any information (about COVID-19 or other topics) in Mandarin; she relied instead on information in Mandarin, regardless of its source, circulating on the communication app WeChat.[50] When we examine the accessibility of such information in the case study, it becomes clearer why LOTE-using communities in Australia may not access government-produced multilingual information, and may not even know it exists or expect it to exist.

In 2020, I began a case study of official COVID-19 communications in Australia (‘Australian case study’). This was prompted by the emerging findings of my earlier NSW study (introduced in Part I) and by research undertaken by a non-government organisation in Australia early in 2020 which indicated that LOTE speakers were not able to access sufficient, reliable information about the pandemic:

A small yet concerning survey of 200 people conducted over the past month by Cohealth — a Melbourne not-for-profit community health organisation focused on migrant communities — found that one in five, or close to 22 per cent, of their clients did not understand COVID-19 information, or had not received it at all.[51]

My case study was also prompted by reports that Indigenous media organisations across Australia needed to ‘drop everything’ to translate public pandemic communications into Aboriginal languages because the pandemic communications were ‘being produced in Canberra and they don’t know the local languages out here’, with delays expected in regard to both written and oral messaging: ‘It’s going to take probably a week by the time they sort out the scripts, and by the time we get here and record them, it’s going to be a week away’.[52] A week is a long time in a COVID-19 outbreak. That communities in the Northern Territory rely on these languages should not have presented an unexpected challenge. This example of a lack of planning for LOTE communications suggested that my earlier findings about the lack of a LOTE communications decision-making framework in NSW[53] were echoed in other Australian jurisdictions, with serious consequences.

My case study collected original data on the NSW and federal governments’ public pandemic communications through in-person and online fieldwork, as well as through exploratory interviews conducted by phone and email with community sector workers engaged in using or creating public pandemic communications in LOTEs. Government and media reports on Australian communications were collected from early 2020 onwards to contextualise the data. Most reports were about the NSW, Victorian and federal governments’ communications, owing to the locations of COVID-19 outbreaks.

I began in-person fieldwork in May 2020, a few months into Australia’s COVID-19 pandemic experience, when rules were being changed and public health information was regularly being updated in English after the first lockdowns. This was an important time for disseminating information. I first examined physical signage and then online communications. I examined public signage about COVID-19 in a sample of four Sydney suburbs. I selected suburbs with more than double the national rate of households in which a LOTE is spoken: Chatswood, Artarmon, Strathfield and Burwood. Given the public health rules in place at the time, many other areas were not accessible for in-person fieldwork, and surveying four suburbs expended my available time and health risk tolerance. Within the four sample suburbs, I quantified instances of multilingualism and recorded both the languages used and the positioning of signage about COVID-19.[54] For comparison, non-pandemic signage in LOTEs was also documented.

I then examined online public health communications from the federal and NSW governments on Twitter, YouTube and the official websites of:

• the federal government;

• the federal Department of Health;

• the NSW Department of Health (‘NSW Health’); and

• the NSW Multicultural Health Communication Service (‘NSW MHCS’).

I chose online communications because they were especially important at the time; access to information displayed in public or transmitted via in-person communications was reduced as public activity was restricted. I chose these specific social media handles and channels because of their official status and prominence. A larger scale study would have yielded more data, but was neither feasible nor necessary given that my initial purpose was to submit timely information to a mid-2020 Senate inquiry into the federal government’s responses to COVID-19.[55]

My and Alyssa Severin’s pre-pandemic research in NSW, Australia’s most populous state, had found that online public communications from 24 NSW government departments and agencies were unpredictable and inconsistent in their language choices, not aligned with the linguistic profile of the public, likely to be in English, and likely to be communicated in writing across departments and agencies.[56] Overall, my COVID-19 case study found the same shortcomings in NSW and federal pandemic public health communications.

1 Physical Signage Findings

Although both the federal Department of Health and NSW Health produced English and LOTE posters about COVID-19 which were free to download,[57] none were widely displayed in the four sample suburbs. English-medium signage from NSW Health was, likewise, not widely displayed. The A4 version of the federal government’s ‘Keeping Your Distance’ poster, in English (see Figure 1), was more commonly displayed than any other government COVID-19 signage, even in shopfronts that otherwise used LOTE signage.

The A4 version of the federal government’s ‘Keeping Your Distance’ poster, in English (see Figure 1), was more commonly displayed than any other government COVID-19 signage, even in shopfronts that otherwise used LOTE signage.

Moreover, the case study found that in NSW some local governments were undertaking LOTE-medium communication of public health information via their own public signage, but other local governments were not, despite serving equivalently high proportions of LOTE-using households. The leading example in this study was Strathfield Council, which produced and displayed many large posters in English, Mandarin and Korean in hub areas (see Figure 2).

|

|

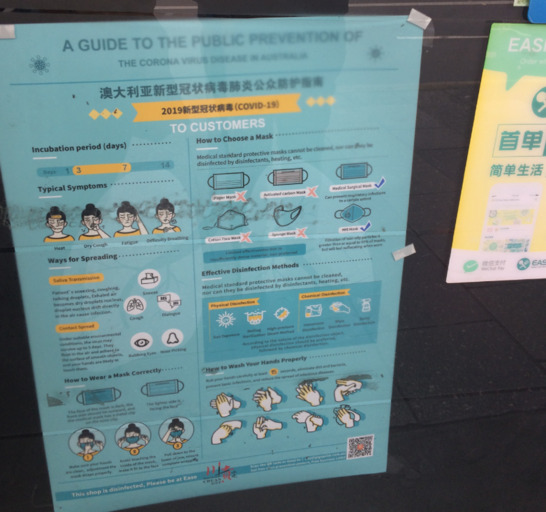

Such local government public health signage chiefly communicated the message of social distancing, rather than the regularly changing rules and details of the official public health response. In this case study, LOTE-medium COVID-19 signage was, overall, less often a government publication than a non-government (unofficial) publication (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Bilingual (English and Mandarin) pandemic signage (‘A Guide to the Public Prevention of the Corona Virus Disease in Australia’) from a consortium of local LOTE media companies, displayed in a shop window, Burwood Road, central Burwood, Sydney (May 2020, photograph by author).

2 Website Findings

Turning now to online communications, the case study found that public health information about COVID-19 in LOTEs, including downloadable information, did exist on the federal and NSW government websites. However, it was located within webpages that were in English, was difficult to search for, and was given opaque and inconsistent labels.

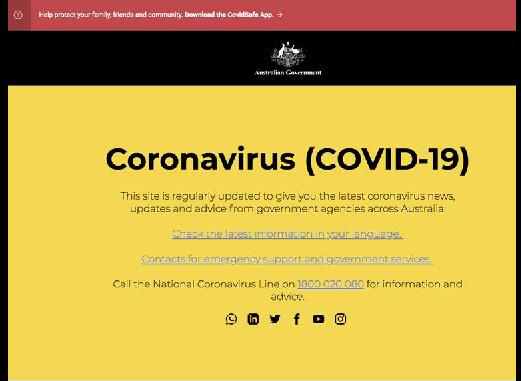

Of the four websites studied, the federal government website’s public health information about COVID-19 in LOTEs appeared to be the most accessible to a non-dominant user of English. This accessibility was achieved in two ways. One was via a prominent ‘Check the latest information in your language’ link on the home page (https://www.gov.au), albeit in English (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: LOTE resources could be accessed via the ‘Check the latest information in your language’ link in the middle of the federal government home page (26 May 2020).

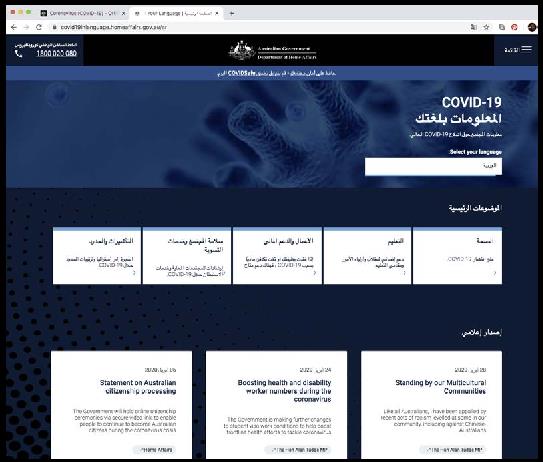

The other was via the ‘Select your language’ menu on the ‘COVID-19 Information in your Language’ webpage,[58] which listed each available language in both English and that language’s script, increasing readability for those with difficulties reading English. Selecting a language converted this webpage’s text, providing detailed public health information in a LOTE (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: The webpage displayed after selecting ‘Arabic / [Arabic]’ from the ‘Select your language’ drop-down menu on the federal government’s ‘COVID-19 Information in Your Language’ webpage (26 May 2020).

By contrast, on the federal Department of Health home page (https://www.health.gov.au), there was no mention of or link to any information in a LOTE (about COVID-19 or anything else). Scrolling to the bottom of this English-only page, I found the words ‘Check our collections of resources and translated resources for more information about COVID-19’ hyperlinked to the ‘Translated Coronavirus (COVID-19) Resources’ webpage.[59] The latter webpage began with notices in English about the COVIDSafe app’s availability in LOTEs, and hyperlinked the words ‘You can also visit our YouTube channel to view SBS’s COVID-19 video in various languages’. However, it also included a list of bilingual hyperlinks such as ‘Coronavirus (COVID-19) resources in Korean ([Korean])’. Each link took the user to a bilingual page with multiple, downloadable resources in a LOTE, including fact sheets, infographics, posters and videos.

A note on the SBS videos mentioned above: these are COVID-19 ‘explainer’ videos in dozens of languages, produced in 2020 and available on the SBS website[60] and the federal Department of Health’s YouTube channel. These were not updated for every change of information, but new videos were added such as ‘Australia’s Three Step Plan for Reopening after COVID-19’ and videos about the 2021 COVID-19 vaccine rollout. The YouTube viewer numbers are publicly available, and were relatively low at the time of the case study. For example, the SBS video on COVID-19 in Mandarin hosted on the federal Department of Health’s YouTube channel was viewed 415 times between 30 March and 26 May 2020. The SBS video in Arabic hosted on the same channel had 1,587 views in the same period. Both numbers of views seem low given these are Australia’s two most-spoken LOTEs and given both videos were hyperlinked on the federal Department of Health’s ‘Translated Coronavirus (COVID-19) Resources’ webpage.[61]

The NSW Health and NSW MHCS websites did not make public health resources in LOTEs readily accessible. The main websites of NSW Health were the NSW Health home page (https://www.health.nsw.gov.au) and the NSW Health ‘COVID-19 (Coronavirus)’ webpage.[62] If a user of these webpages clicked on the red button labelled ‘NSW Gov COVID-19’, they would reach a third NSW Health webpage titled ‘HELP US SAVE LIVES’.[63] None of the three websites provided a ‘choice of language’ button or language menu, or made any mention of LOTE resources.[64] Moreover, these NSW Health webpages did not make any explicit mention of, or link to, the NSW MHCS website.

On the MHCS website (https://www.mhcs.health.nsw.gov.au), I encountered a different barrier to finding COVID-19 information in LOTEs: the home page’s ‘Quick Link’ to ‘Multilingual Resources’ did not link to COVID-19 resources but rather to a database of all MHCS publications.[65] This database was searchable; however, if you searched the name of a language, the results were only listed in English. Only by clicking on an English-medium search result could a user reach a list of multiple resources in LOTEs, and then browse them for COVID-19 information.

These findings about websites’ poor accessibility align with media reports,[66] and build on two other small, contemporaneous studies revealing accessibility problems in the readability of government webpages, even those in English. In the first study, Health Literacy Hub scholars examined the federal Department of Health website in early 2020, finding that ‘basic first principles for a responsive health literate approach have not been followed’ and that readers would need an average of 14 years of schooling (in English) to understand the complexity of the text.[67] The scholars noted that, by contrast: ‘International guidelines for good communication (such as those from the Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention in the US, and the World Health Organization) recommend achieving a grade 8 reading score or less for the general population and grade 5 for lower literacy populations for written health information.’[68] In the second study, leading applied linguist Ingrid Piller assessed two NSW government COVID-19 websites — titled ‘What You Can and Can’t Do under the Rules’ and ‘Public Health Orders and Restrictions’ — using similar, accepted measures of readability. She found that ‘[w]ith a Flesch Reading Ease score of 48.1 and 33.2 both are considered difficult to read, at the reading level of a college student’.[69] As Piller concludes: ‘[T]hat key information about COVID-19-related restrictions are out of the reach of more than 13.7% of the Australian population — irrespective of whether English is their main language or not — is concerning’. Moreover, an ABC investigation found that, while the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services website included COVID-19 information in more than 57 languages,

[t]hose pages were out of date and didn’t reflect the information on the English website. They also linked back to the English website for critical information, such as where to get tested and the reopening roadmap. In one instance, a key point on the Indonesian page was instead translated into Turkish.[70]

3 Twitter Findings

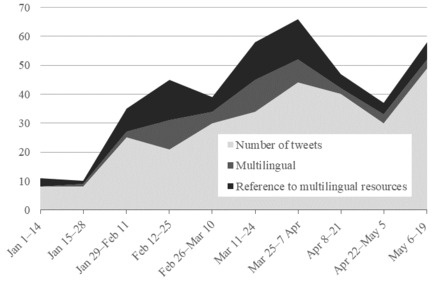

Finally, my case study examined the dissemination of official public health information about COVID-19 via three Twitter feeds: @healthgovau (federal Department of Health), @NSWHealth (NSW Health) and @mhcsnsw (NSW MHCS). These were studied over three fortnights during the early government response to the COVID-19 pandemic: 12–25 February 2020, 11–24 March 2020 and 22 April – 5 May 2020. Key results include the finding that the federal Department of Health, NSW Health and the NSW MHCS increased their Twitter usage in 2020, but all three Twitter feeds were maintained primarily in English. Moreover, important changes in NSW’s COVID-19 restrictions in April and May 2020 were not consistently met with an increase in the number of multilingual tweets (that is, tweets including at least one LOTE in the text or image). Rather, during one relevant fortnight of changing restrictions (22 April – 5 May 2020), for example, multilingual tweets about COVID-19 became a smaller proportion of both NSW feeds: see Figure 6.

Figure 6: Multilingual COVID-19 Information from NSW MHCS on Twitter, 2020

As the number of @mhcsnsw’s tweets increased in response to COVID-19, the MHCS’s use of at least one LOTE within this Twitter feed did generally increase, however. This is shown in the ‘Multilingual’ series in Figure 6. This multilingual tweeting was most common in the fortnights 12–25 February and 11–24 March, corresponding to two high-profile outbreaks of COVID-19 linked to travellers from China and Iran. There was also an increase in @mhcsnsw’s tweets referring to multilingual public health information resources (produced by the NSW government and by SBS) during these times. This increase is shown in the ‘Reference to multilingual resources’ series in Figure 6. Sometimes these references to multilingual information were within multilingual tweets, and sometimes within English-only tweets.

The feed @NSWHealth was more widely followed that @mhcsnsw, with 44,800 followers (equivalent to 0.59% of the NSW population), and it tweeted more often than @mhcsnsw. Despite producing a greater number of tweets, the multilingual tweets from @NSWHealth were fewer in number than the multilingual tweets from @mhcsnsw.

While the federal @healthgovau feed was more active than either of the NSW feeds and had many more followers, multilingual tweets remained consistently absent from @healthgovau from February through to May 2020, even though its total volume of tweets increased.[71] Although the federal Department of Health had produced fact sheets, posters and other resources relating to COVID-19 in LOTEs by May 2020, it did not mention them at all in its tweets during the periods studied.

Supplementing my data, I assembled media reports of problems with the multilingual reach of Australian governments’ COVID-19 information from numerous media outlets citing spokespeople from community organisations, peak bodies and public health professionals. These reveal that the federal government ran a COVID-19 communications campaign costing some $30 million (including English-medium communications; there is no reported figure specifically for LOTE communications).[72] Yet problems with the multilingual reach of federal public pandemic communications persisted throughout 2020, with examples from Afghan, African, Chinese, Greek, Korean, and Muslim Women’s community groups.[73] In mid-2020, the chief executive of the Federation of Ethnic Community Councils Australia was reported as saying:

Unfortunately, often what we see in government policy and programs for multicultural communities and other vulnerable community members is always a band-aid solution ... It’s always an afterthought, rather than, let’s say, bringing in vulnerable members of the community early to make sure the solution we’re trying to design is inclusive of everyone.[74]

Around the same time, the National COVID-19 Health and Research Advisory Committee reported to the federal government that migrants were less likely to receive public health information than others in Australia because government engagement was sporadic, and that this was increasing migrants’ risks of contracting COVID-19 and transmitting it unwittingly.[75] The Committee advised the nation’s Chief Medical Officer that ‘community representatives [told] the panel they were involved in Australia’s COVID-19 response “on an ad-hoc basis or not at all”’.[76] The Committee’s public report of May 2020 concluded: ‘Communication materials should be translated by accredited translators and tailored communications are necessary to increase participation in COVID-19 public health measures’.[77] It noted that ‘some languages spoken by migrants and refugees lack a formal written language ... Provision of information in oral forms will not only allow better understanding, but encourages distribution through established social media and WhatsApp groups’.[78] And yet, when a spike of cases occurred the following month in Victoria,

[t]he company engaged by the Victorian government to manage crisis communication with the state’s 1864 confirmed virus cases was only asked to communicate in languages other than English [some days in], with insiders admitting language had been a ‘blind spot’.[79]

Moreover, the insufficient multilingualism of government communications re-emerged as a prominent concern in 2021 when the vaccination campaign began.[80] Certain government officials confessed that there had been inadequate COVID-19 communication in LOTEs.[81] After reports in 2020 over the ‘nonsensical’ auto-translation of Victorian and federal COVID-19 fact sheets,[82] Melbourne Design Week 2021 even included an exhibition ‘devised in response to translation errors and confusing information regarding COVID-19 ... Artists from non-English speaking backgrounds were invited to create posters in languages other than English to make the COVID-19 safety messages clear’.[83] Together, the assembled sources indicated a communications problem that was not yet solved.

While my case study lends support to the claims reported in the Australian media that government communications in LOTEs often did not reach non-English-dominant individuals and communities in Australia, highlighting such problems is not to dismiss the efforts at multilingual communication made by the state and federal governments. There is evidence that Australian governments made concerted improvements to their COVID-19 communications in LOTEs over time. For example, on its third day of televised COVID-19 press conferences, 28 January 2020, the NSW government included an Auslan interpreter, and from April 2020 this was a regular feature;[84] however, in 2022 the lack of Auslan interpreting for COVID-19 bulletins was still concerning Deaf Queenslanders.[85] Nationally, in February 2020, a multilingual hotline was set up,[86] and particularly at the start of the pandemic, attempts were made to prioritise translation into languages associated with then-key source countries.[87] Later in 2020, the Victoria Government set up the Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Communities Taskforce ‘as part of a $14.3 million initiative aimed at providing culturally specific support and communication’.[88] An executive director of the Multicultural Centre for Women’s Health was reported as saying that ‘migrant groups had been “excluded” in public engagement well before the COVID-19 pandemic began’ but that since the Taskforce had been established ‘communication had improved ... and community groups and leaders had been better engaged to work with the State Government on their plans’.[89]

In 2021, at least one collaborative government–academic research project commenced, in NSW, to look into linguistically diverse people’s COVID-19 communication needs.[90] The Victorian government hired ‘50 women ... to travel to communities across the state to give seminars, hold Zoom sessions, doorknock public housing and answer questions about the vaccine, the virus and other health issues in their own [non-English] language’.[91] At the federal level, a working group of medical experts and language and communications experts produced a resource set called The Science of Immunisation for the federal Department of Health to support the vaccination program;[92] ‘questions of linguistic inclusion and communicative accessibility played an important role in the development of the resources’.[93] In addition,

on top of the government’s $31 million COVID-19 vaccination public information campaign, $1.3 million had been allocated to multicultural organisations to help reach CALD [culturally and linguistically diverse] communities.

‘The National Vaccine Campaign includes advertising translated in 32 languages for multicultural audiences across radio, print and social media — this includes WeChat and Weibo ...’

The Department is also exploring other social media channels to reach multicultural communities.[94]

Further, the Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Communities COVID-19 Health Advisory Group was set up in 2021 by the federal Department of Health.[95]

Australia entered the pandemic with some state and territory governments having more experience in multilingual health communications than others. The NSW government already had its MHCS. The Service’s approach to COVID-19 communications was to produce videos and written materials in the most frequently spoken languages as well as written materials in languages of new and emerging communities and in refugee communities’ languages.[96] According to MHCS Director, Lisa Woodland, NSW’s health communications are generally ‘a little bit different’ to those of other state and territory governments because the focus is on working with communities through ‘co-designed processes’ and responding to community needs; this includes producing audio-visual LOTE materials featuring ‘trusted sources’ such as community leaders, and disseminating written resources through multicultural networks.[97] By September 2020, the Director reported, NSW had published over 900 communications resources about COVID-19 in over 50 languages.[98] NSW Health also had its NSW Plan for Healthy Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Communities: 2019–2023, although, upon inspection, this Plan deals with interpreting communications with individual non-English speaking clients of health services rather than with making public communications accessible in multiple languages.[99]

These comments on NSW’s unusually inclusive health communications are reassuring, but the implication for other jurisdictions is not positive, and even NSW Health’s and NSW MHCS’s COVID-19 communications had some significant shortcomings in accessibility, as my investigation found. Queensland,[100] Western Australia[101] and the Australian Capital Territory[102] have something akin to NSW’s MHCS, but within their health departments, and South Australia’s Department of Health has a ‘Multicultural Communities COVID-19 Advice’ website with LOTE resources.[103] Tasmania’s Department of Health previously described an internal ‘multicultural health’ section on its website but no longer does; it is unclear if that service continues.[104] Victoria does not have such an agency or sub-department,[105] and its Delivering for Diversity: Cultural Diversity Plan 2016–2019 had lapsed by the time of the pandemic. Thus, all other Australian jurisdictions appeared to have less of a multilingual health communications policy framework than NSW, which itself had only a patchy framework.[106]

The case study reported in Part III gives empirical support to fears of unequal access to public information about COVID-19 from government sources, illustrating how communicative injustice has high health stakes and exacerbates marginalisation. This part of the article discusses the implementation of linguistic non-discrimination in fulfilling international right-to-health obligations to prevent continued communicative injustice in Australia. It uses the facts and findings of the Australian case study, and emerging expectations from the international commentary which I identify, to show how even a state party making efforts at multilingual COVID-19 communications (such as Australia) may need to progress.

My analytic review of the international organisations’ commentary does not suggest that a legal standard has crystallised; as noted in Part II above, the absence of new case law hinders this, but even short of that, more consensus-building is needed. However, I have distilled the recent international commentary into emerging expectations about multilingual public health communications’ effectiveness, community input and strategic planning. I propose these as emergent standards around which dialogue should continue. This discussion also argues that emerging expectations as to a proportionate state response are demanding, at least in a pandemic: given the high stakes, states should include most or even all of the languages used by segments of their public. To begin, the key commentary texts are recapitulated to show mounting expectations that states provide multilingual public health communications within a rights-based approach.

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, the CESCR released its Statement on the Coronavirus Disease which warned plainly of the dangers of governments not communicating up-to-date, reliable information in multiple languages:

Accurate and accessible information about the pandemic is essential both to reduce the risk of transmission of the virus, and to protect the population against dangerous disinformation. Such information is also crucial in reducing the risk of stigmatizing, harmful conduct against vulnerable groups, including those infected by COVID-19. Such information should be provided on a regular basis, in an accessible format and in all local and indigenous languages.[107]

Similarly, the WHO explained:

The problems of misinformation, disinformation, a lack of information, and information presented in a way that is not accessible to some communities have increasingly been identified as a significant exacerbating factor during other recent health emergencies, but COVID-19 has given the issue a global dimension.[108]

The outgoing Special Rapporteur on Health specifically raised problems of language barriers and discrimination in access to information and services in relation to the realisation of the right to health during the COVID-19 pandemic in his final report to the General Assembly in 2020,[109] and reinforced that the ability to realise the right to health, whether during a crisis or not, requires ESC rights to be ‘embraced’.[110] These international organisations and office-bearers were not alone in sounding warnings. From early in the pandemic, the Council of Europe’s Committee of Experts publicly urged governments to go further than before with their multilingual public health communications.[111]

Furthermore, international awareness was building in the decade prior to this pandemic about the need for further efforts from both states and international organisations to realise the rights of linguistic minorities. Thus, in 2013, the UN Independent Expert on Minority Issues reported to the UN Human Rights Council that ‘challenges to the enjoyment of the rights of linguistic minorities exist in all regions’[112] and specifically identified ‘the provision of information and services in minority languages’ as one of nine areas of concern.[113] This led to the publication in 2017 of Language Rights of Linguistic Minorities: A Practical Guide for Implementation (‘2017 Guide’).[114] The pandemic provided the 2017 Guide with newfound currency.

While the pandemic-prompted commentary provides the momentum to develop shared expectations, the 2017 Guide provides details. It offers a threshold to meet, and from which to progress, in the realisation of linguistic non-discrimination in health and healthcare, maintaining that ‘linguistic rights issues ... should be considered in any activity that involves state authorities and language preferences’.[115] This means most or all activities because even Australia’s choice to communicate in English is, itself, a language preference. The 2017 Guide sets out a ‘recognize–implement–improve’ method for ensuring that state authorities effectively comply with their obligations’:[116] that is, a progressive realisation approach. The 2017 Guide’s approach includes the following steps, and is guided overall by the principles[117] of dignity, liberty, equality and non-discrimination, and identity:

1. respect the integral place of language rights as human rights;

2. recognize and promote tolerance, cultural and linguistic diversity, and mutual respect, understanding and cooperation among all segments of society;

3. put in place legislation and policies that address linguistic rights and prescribe a clear framework for their implementation;

4. implement their human rights obligations by generally following the proportionality principle in the use of or support for different languages by state authorities, and the principle of linguistic freedom for private parties;

5. integrate the concept of active offer as an integral part of public services to acknowledge a state’s obligation to respect and provide for language rights, so that those using minority languages do not have to specifically request such services but can easily access them when the need arises; [and]

6. put in place effective complaint mechanisms before judicial, administrative and executive bodies to address and redress linguistic rights issues.[118]

These six steps and four principles guide ‘what should be done’ — namely, ‘where practicable, clear and easy access should be provided to public health care, social and all other administrative or public services in minority languages’.[119] The Guide then explains why, on what legal basis, and gives examples of ‘good practices’.[120]

Readers will note that step 4 explicitly integrates proportionality. Crucially, the 2017 Guide provides more detailed guidance than is found elsewhere in the international commentary on proportionality:

[P]rovision [of public health information in minority languages] depends largely, although not exclusively, on the number and concentration of speakers. This will determine the extent to which and areas where the use of minority languages will be seen by the relevant authorities as reasonable and practicable ... [However] [t]he more serious the potential consequences are of not using minority languages ... the more responsive policymakers should be to addressing effective service delivery and communication with this segment of the public ...[121]

That is, it is sometimes reasonable and justifiable for Australia to choose to communicate about health in only some languages, based on numbers of users; however, Australia should strive to use even small group languages when the stakes of not reaching those users are very high, as they have been during this pandemic. I note that small language groups often comprise new migrants who are not well connected to public communications channels or public services; the stakes of not reaching such a group may therefore be particularly high.

In short, Australia should be considering the 2017 Guide’s steps and principles every time it makes a public health communication. When an Australian government chooses to use only English or only a few languages, it should be satisfied that not using additional languages is reasonable and practicable. One possible justification for excluding languages may be that Australia has inadequate funding for wide-ranging multilingual pandemic communications, but this justification is questionable in the COVID-19 context because there has been ample international acknowledgment that the cost of ‘[n]ational pandemic preparedness ... is a fraction of the cost of responses and losses incurred when an epidemic occurs’.[122] That is, in Australia’s proportionate realisation of the right to health without discrimination on the basis of language, excluding some minority languages from public pandemic communications is hard to justify. And indeed, it is not clear that Australia faced this zero-sum financial limit anyway; perhaps it could have spent more on an expanded range of COVID-19 communications, or spent the same amount but on communications that hewed closer to the emerging expectations, explored in the sections below, as to effectiveness, community input and strategic planning.

Thus, there is a strong argument that Australian governments’ public health communications during this pandemic should have been in most or all of the languages used across the country, as a proportionate improvement in Australia’s realisation of the right to health. It is the serious consequences of linguistic exclusion that shift the proportionality calculus. However, as the case study illustrated, the inclusion of minority languages was highly variable. My pre-pandemic NSW research showed the same,[123] suggesting a longstanding problem. More awareness of the rights-based, principled approach to which Australia has committed should prompt inclusive communications by underscoring that access to public information, and to autonomous decision-making and healthcare because of that information, are matters of justice and government responsibility.

Moreover, it is important to note that any advances made in Australia’s multilingual health communications in response to COVID-19, including in the aspects discussed in the sections below, should be sustained after the pandemic unless there are justifications for unwinding them. The CESCR holds that

any deliberately retrogressive measures ... would require the most careful consideration and would need to be fully justified by reference to the totality of the rights provided for in the Covenant and in the context of the full use of the maximum available resources.[124]

Let us now turn to key emerging aspects of compliant communications: effectiveness, community input, strategic planning, and accountability against domestic laws. Each is a form of respecting the integral place of language rights as human rights and promoting tolerance, cultural and linguistic diversity, which were part of the 2017 Guide’s first two steps, as noted earlier.

My review identified increasing expectations that the realisation of art 12 of the ICESCR entails ‘effective’ public health communications. In 2021, WHO published the COVID-19 Strategic Preparedness and Response Plan (‘SPRP 2021’) with its accompanying Operational Planning Guideline containing the ‘National Action Plan Key Activities’ checklist,[125] as well as WHO’s Response to COVID-19.[126] The SPRP 2021 reminds us that ‘[p]roviding individuals and communities with actionable, timely and credible health information online and offline remains a key priority for successful implementation of activities across all pillars of the response’,[127] proposing lessons, strategic objectives and pillars for national-level preparedness and response which emphasise the importance of overcoming communication problems. One of the nine key lessons and challenges for 2021 it lists is: ‘Public health and social measures to control COVID-19 ... must be risk-based, regularly reviewed on the basis of robust and timely public health intelligence [and] effectively communicated’.[128] Another is:

The infodemic of misinformation and disinformation, and a lack of access to credible information continue to shape perceptions and undermine the application of an evidence-based response and individual risk-reducing behaviours. However, empowered, engaged, and enabled communities have played a key role in the control of COVID-19.[129]

The SPRP 2021 further advises states to provide ‘high-quality health guidance ... that is accessible and appropriate to every community’.[130] This is somewhat reflected in the WHO’s own practices: for example, a separate WHO document explains the Information Network for Epidemics whose work includes tailoring WHO guidelines for ‘different communities of users, and translat[ing them] into many different languages’.[131] WHO information about the pandemic was produced in Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Russian, Spanish, German, Hindi and Portuguese,[132] which is more than its six official operating language; however, ‘in practice English predominate[d], as it is the language of [WHO] press conferences and the immediate “language of record” in a fast-changing information environment’.[133]

‘Effective’ public communication was likewise named in the list of urgent ‘non-pharmaceutical measures’[134] in the Independent Panel’s 2021 report. That report is blunt about the threat of repeated pandemics unless preparedness and responses improve immediately, warning plainly: ‘Vaccination alone will not end this pandemic. It must be combined with testing, contact-tracing, isolation, quarantine, masking, physical distancing, hand hygiene, and effective communication with the public’.[135] The report is specific in offering recommendations along with timelines for their implementation and demands that national governments immediately apply these measures systematically and rigorously.[136]

The communications in my case study were not found to be monolingual, or completely ineffective; Australian governments made mistakes but also made efforts to reach a multilingual public. However, using international commentary as a guide, we can see how more effective communications could have been achieved. Moreover, they should have been achieved. The rights-based approach, specifically Australia’s progressive realisation obligation, requires that Australia regularly inquire into its own and other nations’ multilingual public health communications, and, if reasonable, improve its communications practices in response.

Adopting the ‘Four As’ or ‘4-A Framework’ of effective communication is a practice Australia could have followed. This heuristic is well known to CESCR, having been proposed by the Special Rapporteur on Education two decades ago and since studied and advocated by crisis communications scholars.[137] The ‘Four As’ require that communications need to be available, accessible, acceptable and adaptable to various language groups, which can be assessed through these four questions:

1. Availability: Is multilingual crisis information made available and is it recognized as an essential service?

2. Accessibility: Is multilingual crisis information freely accessible, delivered on multiple platforms, in multiple modes (spoken, written, signed, digital, etc.) and in all relevant languages?

3. Acceptability: Are provisions in place to ensure the accuracy and appropriateness of multilingual crisis information?

4. Adaptability: Are provisions in place to ensure that multilingual crisis communications can be adapted to shifting requirements, technological demands, diverse hazards, and the needs of mobile populations?[138]

From this perspective, the case study suggests that many public pandemic communications were not effective. They were available in as much as some translated, written documents, and a smaller number of LOTE graphics and videos, were on free-to-access websites (government websites, SBS and YouTube). However, shortfalls in accessibility were found: multilingual information was delivered on a small number of platforms (largely via PDFs on websites and not, for example, via official Twitter accounts) in a small number of modes (mainly, digital written texts). The LOTEs were relatively numerous but the extent of information in each language was uneven,[139] and never as comprehensive or up to date as the information available in English. Moreover, the study illuminated basic accessibility problems in navigating English-language government websites to locate LOTE content and a lack of government messaging directing the public to LOTE website content. I noted that other studies have shown the English on such websites is likely inaccessible to many because of its poor readability.[140]

The collected media reporting shows no indication of quality assurance processes being in place to ensure the accuracy and appropriateness of multilingual COVID-19 information in Australia — that is, to ensure that it is acceptable. Rather, errors were picked up by communities following publication and then given media attention. Moreover, there was evidence of a lack of such provisions before COVID-19.[141] There were also indications of their absence in my early exploratory interviews; quality assurance processes may have developed within Australian governments as the pandemic progressed. Auto-translation errors in pandemic communications garnered particular community ire (Part III recapping some of the responses). Auto-translation may seem cheap, but the inevitable auto-translated mishaps will not be fixed before publication unless quality assurance processes are put in place. It is with this emphasis on effectiveness, coupled with the rights-based emphasis on community input discussed in the section below, that a rights-based approach helps to overcome complacency and promote quality in multilingual communications.

Similarly, there was evidence in the media reporting of provisions not being in place to ensure that multilingual crisis communications were adapted to shifting requirements or tailored to reach audiences through the most appropriate mediums. That is, they were not adaptable. During my own exploratory interviews, one community informant noted that governments continued to place public health announcements in LOTE community newspapers in Sydney although these were no longer being distributed to the usual extent because of the public health restrictions. The low numbers of Twitter followers and YouTube viewers cited in the case study likewise suggest that governments’ social media communications had not been adapted to their target audiences, remaining reliant on mainstream channels. The case study’s finding of very low display rates in the physical environment for the free posters in LOTEs which could have been downloaded from state and federal government websites, and the use instead in some cases of posters from local councils and local businesses, also indicates a lack of adaptation by state and federal governments. It potentially also reflects that state and federal materials were not acceptable to LOTE communities.

Australia’s state and federal governments made some COVID-19 information available in a relatively broad range of languages, and made some responsive improvements to these materials’ accessibility over the course of the pandemic (particularly in 2021); but they were also slow to improve, and regularly dismissed concerns by citing the quantity of materials produced, regardless of quality or effect.[142] Although Australian governments produced multilingual public pandemic communications, they did not necessarily aspire to or achieve effective communications, despite international guidance emphasising effectiveness, and despite tools such as the ‘Four As’ being known to international organisations (and scholars).

Moreover, I found that trustworthiness is slowly gaining acknowledgement in the international commentary as part of effective communication. The role of governments’ language choices in building or breaking trust is not emphasised in the commentary although most international organisations operate on a closely related premise that their (formal) multilingualism signals wide inclusion to a linguistically diverse international community. In SPRP 2021, the WHO reminds us that ‘trust building’ is part of pandemic risk communication and management, and remained critical during the vaccination-focused phase.[143] The Independent Panel likewise notes the importance of building trust between governments and marginalised communities.[144] These international bodies single out trust building because it is a key part of converting public communications into behavioural change — that is, into effect. Using a community’s language is known to researchers as an important gesture for developing trust; language choice is a meaningful signal.[145] The media reports examined in the case study show communities feeling disrespected by linguistic errors and exclusion. Yet without a decision-making framework to highlight links between language and trust, I argue that the trust-building role of government communications is easily overlooked in practice. I identified some trust-breaching tactics in NSW Health’s multilingual tweeting in my initial publication of the case study data,[146] which ceased shortly thereafter. While that constituted community input, the international commentary encourages such input at the design stage, and from linguistic minorities.

Community input is raised in the WHO’s SPRP 2021 quoted in Part IV(B) above. The Independent Panel’s report also contains recommendations regarding community engagement in pandemic communications. Recommendation 7 includes:

IV. Strengthen the engagement of local communities as key actors in pandemic preparedness and response and as active promoters of pandemic literacy, through the ability of people to identify, understand, analyse, interpret, and communicate about pandemics.

...

VI. Invest in and coordinate risk communication policies and strategies that ensure timeliness, transparency, and accountability, and work with marginalized communities, including those who are digitally excluded, in the co-creation of plans that promote health and well-being at all times, and build enduring trust.[147]

Significantly, both are assigned to national governments for action, not only national health sector bodies:[148] 7-IV for ‘medium-term’ action and 7-VI for ‘short-term’ action.[149] Recommendation 7-IV is especially clear in its relevance: given Australia’s linguistically diverse public, engaging local, multilingual communities will be part of making local communities ‘key actors’ and building up people’s abilities to be ‘pandemic literate’ and to understand, analyse and communicate information. Recommendation 7-VI’s explicit mention of marginalised communities is an invitation to deliberately include linguistic minorities in designing and executing pandemic communications policies.

Notably, these two recommendations are about preparing for community engagement and community-based communications before a pandemic, in line with the WHO’s more general call for developing communications strategies and networks in advance. Preparation is discussed in Part IV(D) below on strategic planning. These particular recommendations for proactivity in community engagement draw on the Independent Panel’s findings that countries that ‘engaged with community health workers and community leaders, [and] involved vulnerable and marginalised populations’[150] had more success in their COVID-19 pandemic responses, including some countries which had developed robust community engagement and coordination during other health crises.[151]

In Australia, the media reporting assembled in Part III above quotes community leaders’ praise for governments increasingly gathering and responding to community feedback (along with ongoing calls for greater involvement). This appears to be an area where Australia is already improving although proactive community involvement and co-design is not yet embedded. The possibility of embedding such activity brings us to the need for strategic planning.

The COVID-19 commentary by the WHO emphasises strategic planning, to better achieve effective communications and community input, among other advantages. For example, the strategic value of planning for communications that engage various communities is underscored in the SPRP 2021’s explanation of ‘Pillar 2: Risk communication, community engagement (RCCE) and infodemic management’[152] which includes a warning about the need to adapt a state’s COVID-19 response (including, but not only, its communications) informed by communities’ experiences. This RCCE pillar also urges governments to address the ‘removal and mitigation of demand-side barriers to health service access’ and I argue that language barriers must be understood as one of those barriers.

States’ strategic planning may also include some of the specific procedures for identifying language needs and checking the quality of multilingual communications which the WHO’s 2018 Multilingualism report noted.[153] Additional commentary in support of the advanced planning of communications policies, and further content for them, is provided throughout the Independent Panel’s report. A lack of strategic planning and a clear communications policy framework have also been problems that scholars worldwide have noted in public communications — particularly but not exclusively public crisis and pandemic communications[154] — and so changing state practices is this regard during the pandemic has drawn attention. For example, China’s rapid shift from monolingual to multilingual COVID-19 communications has become the object of multiple studies,[155] and O’Brien and Federici have argued that language barriers can be considered ‘part of disaster prevention and management’ rather than only part of a response.[156]

Yet strategic planning seemed lacking across Australia even before the pandemic, as identified in my previous research and in government reports. For example, the Queensland government’s 2014 Language Services Policy Review noted that ad hoc rather than planned LOTE communications were common, as was a lack of data about the quality or efficacy of LOTE communications.[157] My own 2019–20 research and this COVID-19 case study are only a partial response; more data is needed and may already be held by governments.

Asking other countries for language service assistance could be part of strategic planning and would align with another theme of the international pandemic commentary: international solidarity.[158] For example, qualified translators of the languages of new and small migrant groups are often in short supply in Australia but may be abundant in another country where that language is neither new nor small. I have not found any such suggestion in the literature; these dots of international solidarity and planning for linguistic inclusion are yet to be connected.

Finally, my review of the international commentary found an emerging expectation that states not only plan multilingual health communications strategically but secure that planning in law so that linguistic minorities themselves can hold governments to account and prompt improvements. This has not been repeated as often as the emerging expectations identified above in this Part; however, the 2017 Guide declared that ‘[l]egislation needs to codify how and where these [language] rights can be exercised, and ensure that effective mechanisms are in place to address and redress situations of non-compliance’,[159] and its Steps 3 and 6 call for the establishment of legislative and judicial mechanisms. These are calls for domestic legislation as part of the progressive realisation of linguistically non-discriminatory ESC rights. Such calls remind us that difficulties in using legislation to prompt greater linguistic inclusion from Australian governments, or to hold them accountable for exclusion, are likewise faced overseas.[160]

I found little uptake of this call for domestic legal accountability in the commentary about states’ responses to COVID-19, and therefore do not suggest it as a standard around which dialogue is coalescing. However, this is indisputably an area for improvement in Australia in order to progress in the realisation of ESC obligations, and ultimately to improve communicative justice in health.

This research was driven by concerns over communicative justice — specifically, that shortfalls in the multilingual provision of government information about the COVID-19 pandemic contributed to health inequalities and exacerbated certain groups’ marginality, violating international rights to health and linguistic non-discrimination. The pandemic raised the stakes of my and my co-author’s earlier research finding that there is only a patchy framework of laws and policies to guide decision-making for Australian governments’ multilingual public communications or to redress any injustices that those communications — or their absence — might produce. My response has been to investigate the guiding role of international law, specifically ICESCR rights and international organisations’ recent commentary about them, alongside an empirical study of Australian governments’ actual COVID-19 communications.

During this pandemic, I found that Australian governments sometimes communicated in dozens of languages, but at other times used few LOTEs, used them poorly, or buried their use within English-language websites, making authoritative information hard to access for many. I thus examined the possibility of improving the effectiveness, community input and strategic planning of our governments’ public LOTE communications, overall asking whether public communications could better realise people’s interacting international rights to health and linguistic non-discrimination. My case study analysed portions of more than two years of pandemic communications; while the contextual government statements and media reports indicate that the problems persist, further empirical studies of Australian public health communications would bolster the arguments and suggestions for improvement.

My point is not that COVID communications were bungled by Australian governments; certainly, some mistakes were made, but even well-intended multilingual efforts fell short. The analysis presented here suggests that Australia has failed to keep progressing the realisation of ICESCR health rights. Australia’s ICESCR obligations are owed without language discrimination against even small language minorities. We have seen that the negative impacts of the pandemic cascade along lines of linguistic vulnerability; excluding languages from public communications has serious consequences. In pandemic-like crises where not communicating has serious consequences, I have identified an emerging line of reasoning that most or all languages of the public should be used by the government to uphold communicative justice.