University of New South Wales Faculty of Law Research Series

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Faculty of Law Research Series |

|

Last Updated: 4 September 2008

IMF Policies and Health in Sub-Saharan Africa

Ross P Buckley[*] and Jonathon Baker[**]

To be published in the forthcoming volume, Global Health Governance: Crisis, Institutions and Political Economy, Adrian Kay and Owain Williams (Eds), London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008.

Abstract

This paper analyses the impact of IMF policies, initially Structural Adjustment Policies and more recently Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers, upon healthcare in Sub-Saharan Africa. Case studies are undertaken of healthcare outcomes in Tanzania, Uganda and Ghana. Regional statistics for infant mortality and life expectancy are also considered. However viewed, the Fund’s policies have been disastrous – diverting funds from much needed healthcare into foreign debt repayment and foreign exchange reserves, and imposing salary caps that encourage the flight of local doctors abroad. There are few better investments for any developing nation than the health of its own people. The Fund and its policies need to be reconceptualised.

Introduction

Health matters. It is a fundamental human right[1] which supports economic development,[2] and although globalisation is not new,[3] its impact on health is being increasingly scrutinised.[4]

Generally, trade liberalisation is welfare-enhancing because it promotes economic growth and this should, other things being equal, lead to less poverty. Less poverty and the opportunities growth brings for greater expenditures on healthcare should both contribute to improved heath outcomes.[5] A virtuous cycle can therefore arise in which growth promotes health which in turn promotes more growth.[6]

Structual Adjustment was the name given to the policy prescriptions the World Bank (the Bank) and the International Monetary Fund (the IMF or the Fund)[7] developed in response to the Debt Crisis that commenced in late 1982 and afflicted Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa. Once the Debt Crisis erupted, the Fund rapidly assumed the role of crisis-response coordinator and required compliance with its economic policies as a precondition of receiving its and the Bank’s assistance. Through the implementation of SAPs the Bank and Fund sought to achieve sustained economic growth in recipient countries.

This chapter will assess the impact of Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs) and their successor, the Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSPs), on health expenditures and outcomes in Sub-Saharan Africa. Case studies are undertaken of Tanzania, Uganda and Ghana. But before we commence this analysis, a story that highlights the IMF perspective on these issues may be illuminating.

A few years ago I spent an enlightening evening with a senior IMF official. Towards the end of the night, after the consumption of generous amounts of alcohol, and in support of progressive tax regimes, I argued that a further $20 a week of income would mean less to me than to a poor person in Australia. My companion demurred. He responded,

“You cannot say that. The marginal utility of $20 to you may far exceed that to a poor person – economics has established this conclusively. You may invest it in a business, or in your further education or that of your children. A poor person is likely to simply waste it on food or shelter.”

The interchange was telling. Economics, in essence, is the science of increasing the size of the economic pie, in the context of certain assumptions. This senior IMF economist is probably right. A small increment in my income may well be employed more productively, in terms of enhancing Australia’s GDP, than it would in the hands of someone who is poor – while I know I will spend the extra dollars on more or better wine, my companion could not know that, no matter how much evidence our drinking that evening provided to that end. But the highly successful track record of micro-credit argues against the IMF officers assumption that the poor will not put extra income to productive uses, and if the extra income is needed to achieve basic nutrition or shelter who would begrudge this application of the funds?

What we are dealing with here, at core, is not economics in general, but one particular form of economism, market fundamentalism -- a belief that markets are always, invariably, the most efficient devices to achieve service delivery – a belief, especially in poor countries with weak institutions, for which there is very little evidence. This is the belief that gave rise to structural adjustment programs.

Structural Adjustment Programs

SAPs generally included the following elements:[8]

Recipient countries of IMF assistance are required to accept IMF advisers in their Treasury and Ministry of Finance offices who will insist on adherence to the policies listed above. Countries which require IMF assistance often suffer from large budget and trade deficits, rapid inflation, and capital flight.[9] They are rarely in an empowered position from which to argue against the policy prescriptions of the Fund.[10] Nonetheless there is often considerable resistance by recipient countries to the Fund’s imposition of its views – a resistance that in the implementation stage works against the effectiveness of Fund-mandated reforms. IMF policies are accepted, at least in a superficial, formal sense, because recipient nations believe they have no choice in the matter.

There have been numerous criticisms of SAPs by a wide range of commentators, principally from NGOs and academe.[11] The most common criticisms are that SAPs:

A study on SAPs carried out by Harvard University concluded that “the required reductions in public expenditures were imposed on system(s) which were already failing to meet basic social needs.”[12]

The Bank and Fund introduced Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSPs) in response to these criticisms.

Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers

PRSPs were introduced in 1999 in response to the global outcry at the failure of SAPs to reduce poverty significantly.[13] PRSPs were to be a new tool for poverty reduction, debt relief, and access to funding from donors.

According to the IMF, “PRSPs are prepared by the member countries through a participatory process involving domestic stakeholders as well as external development partners, including the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.”[14] PRSPs outline the economic, social, and structural programs to be used to reduce poverty.[15] Instead of focusing on macroeconomic stability and growth like SAPs, PRSPs, as their name suggests, were to put poverty reduction at the core of the nation’s economic policies.

Once approved, the PRSP forms the basis for future funding.[16] Potential recipients of debt relief under the Heavily Indebted Poor Country (HIPC) Initiative and the IMF’s Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility (PRGF) are required to produce a PRSP to be eligible.[17]

That the primary policy focus of PRSPs was to be poverty reduction is evidenced by the requirements that they include:[18]

However, despite these broad changes in form and process from SAPs, it seems the substance of the development policies required of developing countries have changed little.

SAPs were designed to achieve stability and long-term growth. Poverty reduction was not pursued directly because it was assumed it would result from economic growth. This is a perfect example of the ‘market fundamentalism’ analysed by Sparke in Chapter __ ** of this volume. The IMF’s working assumption throughout the 1980s and 1990s was that growth would lead to reduced poverty and improved healthcare automatically by the operation of the market.

Conversely, the primary objectives of PRSPs were poverty reduction and growth.[19] Yet many commentators argue that the PRSPs promote the priorities of the International Financial Institutions (the IFIs) rather than of the poor.[20] The IMF guidelines for constructing PRSPs have strong neo-liberal assumptions, which result in less government intervention in markets and reduced public spending, particularly on education, healthcare and social welfare. Reductions in public spending, virtually inevitably, lead to a weakening or removal of the social ‘safety nets’ needed by the most vulnerable members of society—namely women, children, rural populations, and the poor. To examine the effects of SAPs and PRSPs we will now examine in detail the healthcare situation in Africa.

Africa

Three key healthcare indicators will be analysed for Sub-Saharan Africa: the under-five mortality rate, life expectancy, and infant mortality.

Under Five Mortality Rate

One of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) is to reduce the under-five mortality rate (U5MR) by two-thirds between 2000 and 2015.[21] The median U5MR in Sub-Saharan Africa is 153 per 1000; ie. more than 15 out of every 100 children die before their fifth birthday. This compares to one in 100 in the developed world.[22]

The annual rate of decline in U5MR in Sub-Saharan Africa averaged about 1% in the 1960s, increased to close to 2% between 1970 and 1985, dropped back to about 1% between 1985 and 1990, and averaged less than 1% during the 1990s. These rates of decline pale in comparison to the 4.3% rate required to achieve this MDG.[23] Indeed, Sub-Saharan African is not on track to achieve a single target set by the MDGs for the period 2000-2015.[24]

However, it must be noted that these countries have all been seriously affected by HIV/AIDS or have suffered economic crises or political instability.[25] For these reasons, the numbers are skewed, and progress is hard to track.

Life Expectancy

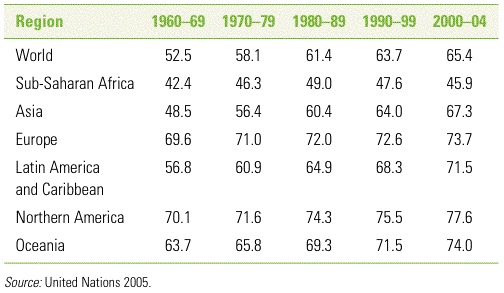

The gap between life expectancy in Sub-Saharan Africa and in Europe and North America in 2000 is larger than it was in 1950.[26] Table 1 summarises the life expectancy at birth for the World and U.N. regions.

Table 1 Life Expectancy at Birth for World and UN Regions, 1960-2005[27]

Life expectancy at birth in Sub-Saharan Africa is a mere 46 years, compared to 67 years in Asia, the region with the second lowest life expectancy. In the 1960s the difference between Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa was only six years. Moreover, where all other regions have experienced continuous increases in life expectancy, Sub-Saharan Africa life expectancy peaked in the early 1990’s at 50 years and has since fallen back by four years. [28]

Over 35 years of increases in life expectancy were reversed in a mere decade,[29] and the UN Population Division predicts that life expectancy will continue to fall in Sub-Saharan Africa in the next 5-10 years.[30] Again this appalling outcome is largely influenced by the AIDS pandemic sweeping the region, so the impact of the healthcare systems on life expectancy is difficult to isolate and analyse.

Infant Mortality

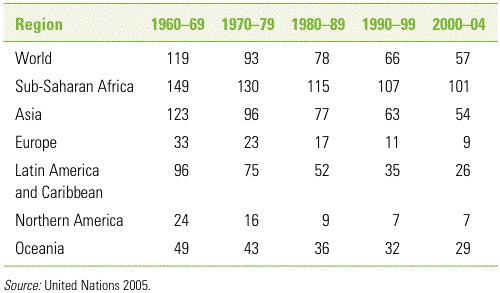

The rate of decrease in infant mortality slowed considerably during the 1990s, further indicating that Sub-Saharan Africa has lagged behind other regions in achieving health outcomes.

Table 2 Infant Mortality Rates for World and UN Regions,

1960-2005[31]

(per

1,000 live births)

In summary, SAPs failed to address effectively poverty or poor health in Sub-Saharan Africa. PRSPs have been with us this decade, long enough to assess their impact. They have the potential to be successful because they are designed to address the specific needs of individual countries through a thorough process of consultation and participation in their formulation. This consultative process is supposed to facilitate communication between all interested parties, and increase the responsibility of Ministers of Health to ensure that the funds get distributed to the poor. PRSPs should allow greater flexibility to achieve specific health needs because there is no set structure for a PRSP. However, problems can arise because there is a fine balance between country ownership, and Bank and Fund approval, of a PRSP.

Whether PRSPs have been effective is another matter. An investigation into specific countries will reveal what has been achieved through the implementation of PRSPs.

Case Studies

Tanzania

When Tanzania applied SAPs during the 1980s and 1990s, the economy grew and yet poverty increased. This was primarily because of a heavy fall in public healthcare funding.[32] With the introduction of the SAP, government spending on health fell from 7.5% of expenditure in 1978 to 3.9% in 1989.[33]

Under the SAP, NGOs and the private sector administered the majority of the health services while the public sector was forced to impose user fees to offset its funding cuts. Private clinics gravitated towards major centres where they were most profitable rather than to the poorest areas where they were most needed.[34] Compounding this, there was little collaboration between NGOs, civil society and the Bank and Fund on healthcare policy.[35]

Tanzania continues to work with the IMF but it is now focused on restoring the health system that was neglected under SAPs. Evidence of this shift in priority is the increase in health spending as a percentage of government expenditure from 7.5% to 8.3% during the period 2000 to 2003.[36]

Nonetheless, healthcare funding in Tanzania remains inadequate to fight priorities such as tuberculosis, malaria and AIDS. WHO figures show that only 46% of healthcare expenditure is publicly funded. Tracking of programme spending is poor, making it very difficult to assess whether and where the funds are being deployed.

The commitment to better service women, children and the rural community are outlined in the PRSP,[37] but user fees effectively negate this commitment. For example, only 36% of women who give birth in Tanzania are attended by trained health personnel and only 38% of children under five years of age receive adequate water and nourishment when experiencing health problems.[38]

Uganda

Uganda is a good example of a country owning its poverty reduction process, having implemented its own Poverty Eradication Action Plan (PEAP) in 1997, prior to its PRSP. However, poverty levels remain high with only 55% of the population above the poverty line. Within the health sector, there are only five physicians per 10,000 people and only 38% of births are attended by skilled personnel.[39]

A primary cause of this problem is that the health sector was ignored under Uganda’s SAPs. In 1997, only 20% of healthcare expenditure was funded by the government, with donors, households and employees contributing the rest.[40]

User fees were implemented in the 1990s to supplement public sector funding and contributed significantly to the fragmentation of the health sector as a whole. The government reduced its role in healthcare to focus on HIV/AIDS and immunisation services rather than primary healthcare distribution.[41] As the government pulled out from primary healthcare, NGOs stepped in but in a disjointed and inefficient manner.

Overall, the health of Uganda’s citizens has decreased. Life expectancy fell from 46.8 years in 1980 to 46.2 years in 2005. Additionally, the level of immunisation of children in the last five years has decreased from 47% to 37%.[42]

Budgetary expenditure on healthcare in 2003 was 9.6% with projections of attaining 15.9% by 2013-2014.[43] However, while these figures appear to offer real promise, the Ugandan Government estimated health expenditures to be roughly US$28 per capita in 2003,[44] yet a subsequent WHO study found the true figure to be US$6 per capita.[45]

In 2001 Uganda became one of the first countries to dump user fees under its PRSP, for the purpose of promoting access for the poor. However, without a concomitant increase in funding, this measure merely served to decrease the quality of services and the availability of drugs and increase the out-of-pocket expenses incurred by patients.[46]

Ghana

Ghana implemented structural adjustment in 1984. Ghana’s GDP per capita was lower in 1998 than in 1975. Seventy-five per cent of Ghanaians currently have no access to health services and 68% have inadequate sanitation.[47] Average healthcare expenditure from 1995 to 2000 was a mere 4.2% of GDP, with 2.2% funded publicly, and the balance funded privately.[48]

Surprisingly, given this funding context, the Bank has reported improvements in lead healthcare indicators. For instance, the U5MR decreased from 185 per 1,000 in 1980, to 160 in 1990, 145 in 2000, and 138 in 2005.[49] Additionally, infant mortality has decreased for the last three decades from 96 per thousand in 1980, to 77 in 1990 and 63 in 2000. Immunisation rates (per 1000) have increased from the low 60s to the low 80s between 1991 and 2001.

In 1985, like many other Sub-Saharan African countries, Ghana introduced user fees for its healthcare system. This added expense coupled to falling wages and rising poverty reduced out-patient attendance at hospitals by a third, with the majority of the decrease occurring in rural areas. As one observer put it, “Patients pay for everything – for surgery, drugs, blood, scalpels, even the cotton wool.” Full cost recovery priced the poor out of healthcare.[50] Nonetheless, Ghana appears to have done exceptionally well with very limited resources.

Role of the IMF

Surveillance, financial assistance and technical assistance are cited as the Fund’s three main functions these days.[51] For countries with an IMF program in place, the Fund has direct input into the fiscal and monetary policy settings of the country. This was not part of the IMF’s original role. The IMF was founded to assist countries in managing their fixed exchange rates by providing funds and technical advice.[52] However, as developed nations moved away from fixed exchange rates in the 1970s, much of the IMF’s original mission disappeared. With the inception of the Debt Crisis in 1982 the Fund moved quickly to secure the role of crisis co-ordinator and today its role is managing crises in emerging markets countries and conducting the surveillance, financial assistance and technical assistance that aims to avert these crises.[53]

The policies through which the IMF tries to achieve these goals have been subject to increasing criticism in recent years.

A United Nations Development Program (UNDP) study[54] has argued that inflation rates associated with healthy economic growth should range from 5-10% or higher, and an inflation rate of less than 5% can have a harmful impact on an economy. Yet a recent study by Oxfam International reported that 16 out of 20 countries within IMF programs in place had inflation targets of less than 5%.[55]

Periods of rapid economic growth in Continental Europe, the USA and Japan were historically associated with large programmes of public expenditure and budget deficits. Yet the current policies of the IMF deny countries the ability to borrow domestically to fund productive programs due to deficit caps. In short, the IMF is hostage to neo-liberalism and economic rationalism. Its policy prescriptions, though well-meaning, are shackled by the very restrictive lens through which all options are considered.

In practice, IMF policies worsen inequalities by removing subsidies and price controls on basic goods and services. The introduction of user fees work against poverty reduction but are necessary to fit within the macroeconomic framework IMF ideology compels it to instil in recipient countries.[56]

The apparent change of IMF policy from SAPs to PRSPs is, on one view, more an effort to rescue the Fund from its crisis of legitimacy[57] than to respond to the needs of the poor in poor countries.[58]

If the IMF is to play a more constructive role in developing countries it needs to provide greater fiscal flexibility to permit increases in government spending so as to assist countries in meeting the MDGs. The IMF should also refrain from requiring trade liberalisation and privatisation as loan conditions because such policies are yet to demonstrate clear poverty reduction effects.[59]

Finally, the IMF needs to further alter its own institutional setup. Notwithstanding the changes in late 2006 to member countries voting rights, developed countries continue to exercise an influence over the Fund that is not proportional to their number or need. Furthermore, the Fund needs to decentralise further and employ more staff with social science backgrounds[60] in order to properly conceptualise strategies for both poverty reduction and economic growth.

The IMF and Healthcare

Consistent with its ideology, the IMF views healthcare as a service better provided by the private sector. There are at least four ways to transfer the delivery of health care services in whole or part from the public sector to the private sector:

Each of these methods is potentially effective except the one employed by SAPs and PRSPs, the first one. Starving government funded healthcare services of funding, and then hoping the private sector will fill the gap, simply doesn’t work very well at all, [62] for at least three reasons:

Before the 1980s essential drugs were provided free of charge in Africa at community health centres. After the introduction of user fees and cost recovery, the sale of drugs was liberalised. The result of this was a decline in consumption of essential drugs. With the deregulation of pharmaceuticals, imported brand name drugs were released into the free market and eventually displaced domestic drugs. By 1990, domestic production of pharmaceuticals had virtually stopped as the companies were forced into bankruptcy.[66]

Compounding these problems, SAPs and PRSPs tend to advocate devaluing the local currency in an effort to encourage exports. However, a cheaper local currency dramatically increases the costs of imported pharmaceuticals.

Liberalisation of the health sector tends to shift resources towards specialised centres catering for the affluent few and foreigners, while depriving the people in rural areas, thus creating a two-tier delivery system which worsens the already inequitable distribution of healthcare resources.[67] Furthermore, the diffusion of new health technologies to developing countries usually only benefits the wealthy at the expense of an under-funded public healthcare system geared towards servicing the poor.[68]

Researchers have compared the cost per admission and per in-patient day, in southern Africa, between public rural district hospitals and subcontracted private hospitals.[69] Their study revealed that efficiency did not increase when the hospital was leased to private companies. The research suggested that similar quality of care can be achieved at a lower cost when provided solely by the public sector. Private care came at a higher cost because the profit margins more than offset any efficiency savings.[70]

One way to illustrate why private health care fails in poor countries is to explain how it succeeds in rich countries. In Europe and Australia, governments regulate and control the private sector and there are detailed contracts for healthcare providers and detailed oversight of their implementation. In lower and middle income countries, this monitoring tends not to happen effectively because of weak public institutions.

Even the contracting out of clinical services to non-profit providers such as church hospitals is a very complex operation. It may be that only strong democratic governments in developed countries possess the regulatory resources to properly regulate the delivery of quality healthcare by the private sector.[71]

Do PRSPs represent progress?

As the data tables indicate, if PRSPs are delivering better healthcare outcomes in Sub-Saharan Africa the improvements are not clear or substantial.

Furthermore, there is little evidence that nations are more empowered in policy decision making under PRSPs than their predecessors. If programs were truly national creatures, tailored to each individual nations’ needs, one would expect some PRSPs to exhibit strategies that differ from the standard policy prescriptions of the past. But this is not the case – the PRSPs of virtually all countries are strikingly similar. The macroeconomic policies under PRSPs have essentially been a continuation of the policies under SAPs[72] and PRSPs don’t contemplate alternative approaches to poverty reduction such as resource redistribution.[73]

PRSPs tend to be insufficiently integrated with national planning mechanisms such as the budget and there tends to be too little coordination between different levels of government. [74] A PRSP, no matter who contributes to its conception, is unlikely to be effectively implemented in the absence of such strong linkages.

A further hindrance for PRSPs is the unpredictability of aid transfers upon which the programmes may rely. Currently, there are no sanctions on donors who default or delay payment,[75] and donors are notoriously unreliable in fulfilling their undertakings.

Likewise, if PRSPs were the result of genuine consultation, recipient nations would not be so quick to evade them when they can. For instance, in December 2005 both Brazil and Argentina settled their IMF debts ahead of schedule to avoid adherence to the conditions contained in their respective PRSPs. South Africa, having witnessed the African experience thus far, has refused to borrow from the IMF.[76] Indonesia, a few years ago, repaid its IMF loans so as to be able to reclaim control of its domestic policy settings.

The nations that accept the PRSPs are the low income ones that really have no choice.[77] Middle income countries, as the above examples indicate, are showing an increasing willingness reject the IMF, and its funding, so as to have control over their own policies.[78]

In short, the names have changed but the game appears to have stayed the same.[79]

2007 – Update

We commenced researching this paper in January 2007. A quick check before completing it, revealed two significant 2007 publications – each of which, happily, served to reinforce our analysis and conclusions.

The IMF has its own internal evaluation division, the Independent Evaluation Office, and in March it released an Evaluation Report, “The IMF and Aid to Sub-Saharan Africa”.[80] The Report concluded that there were differences of views among the Executive Board of the Fund about the IMF’s role and policies in poor countries, and that

“lacking clarity on what they should do on the mobilization of aid, ... and the application of poverty and social impact analysis, IMF staff tended to focus on macroeconomic stability, in line with the institution’s core mandate and their deeply ingrained professional culture.”[81]

In other words, some seven years after the replacement of SAPs with Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers, and some seven years after the establishment of the Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility, IMF staff were unclear on the priority to be give to poverty reduction and how to achieve it, and so sought to attain that which they knew how to attain, macroeconomic stability. In the first year or two of the introduction of new priorities and programs this would be understandable though still regrettable. After seven years this is simply ridiculous. For an institution that is the subject of unremitting criticism for the impact of its programs and policies on poverty, and which has been maintaining steadfastly in all its press releases and public pronouncements since 2000 that poverty reduction is its highest priority, to still be trying to bed down new initiatives and priorities on poverty reduction over seven years after their introduction is utterly unacceptable. In most corporate or government settings, one would expect such non-performance to result in the sacking of senior staff.

The Report also found that the Fund’s policies have accommodated increased aid “in countries whose recent policies have lead to high stocks of reserves and low inflation”, but “in other countries additional aid was programmed to be saved to increase reserves or to retire domestic debt”.[82] In other words, extra aid was channelled by the Fund into foreign exchange reserves or to repay debt in most poor countries. This is a perfect illustration of the damage that overly restrictive policy settings on inflation rates can do in developing countries. Such an approach has two flaws:

1. It diverts extra aid away from healthcare, education or other social welfare expenditures, and

2. It risks being a ‘self-fulfilling prophecy’ as diverting aid flows into reserves and debt reduction is likely to dissuade donors from giving more aid. Most donors want to give aid to directly assist suffering people, not to improve the macroeconomic profile of the nation in which they live.

The second major report published this year was by the Center for Global Development and is entitled “Does the IMF Constrain Health Spending in Poor Countries?”.[83] In its words,

“The evidence suggests that IMF-supported fiscal programs have often been too conservative or risk-averse. In particular, the IMF has not done enough to explore more expansionary, but still feasible, options for higher public spending”.[84]

The report also concluded that wage-bill ceilings had been overused and should be dropped from IMF programs “except in cases where a loss of budgetary control over payrolls threatens macroeconomic stability”.[85]

The Fund should not shoulder the blame for these misguided policies alone. After all, it is governed by an Executive Council on which the balance of power is held by the developed nations.[86]

Conclusion

The neo-liberal policies that underpin PRSPs and focus on a smaller role for government in healthcare need to be rethought. Investing in the health of its people is essential for the growth of a nation. The realisable benefits to a nation of providing health care, especially to the poor, far outweigh the costs.

The IMF tends to produce over-optimistic growth projections that inflate expectations of budget revenues, and when governments lack sufficient financing for PRSP priorities, donors and creditors decide the country’s priorities for them.[87] Quite simply, country ownership of the PRSP process is a mirage.

Viewed as a whole, there is no shortage of global health governance.[88] This chapter and those by Labonte[89] and Weber[90] establish that the problem is not an insufficiency of global health governance but the type of governance we have and the philosophy and policies that inform it.

As illustrated through the case studies, there has been a very limited increase in healthcare expenditure since 2000, which suggests health has not been a primary concern of the Fund. The health of the world’s poorest and most vulnerable continues to be unprotected by effective policies and healthcare services. Statistical analysis of healthcare outcomes suggests very little has changed, at least for the poor in Sub-Saharan Africa, since 2000.[91]

Recommendations

Reform is needed at two levels.

At the most fundamental level, the IMF needs to be reconceptualised. Its original purpose largely disappeared in the 1970s with the floating of most rich countries’ exchange rates. Since then it has taken on the role of developing country crisis prevention and management, yet if one had been designing an institution for that role, it would not look at all like the IMF. Its staff would have different skill sets and backgrounds and the institution would have different (and more extensive) powers. The culture within the Fund, particularly its economic perspective, is simply wrong for this role, as its results consistently display.

In the past twelve years there has been considerable reform of the World Bank, fundamental change we are yet to see any evidence of in the Fund. Probably the simplest and most efficacious step is to merge the much-smaller Fund into the Bank and then proceed apace with the renewal of the World Bank – there is little need, any longer, for a separate international monetary fund.[92]

At the operational level, rich countries should continue to increase financial support for initiatives with proven track records, such as the Global Health Fund, and should continue to insist that aid money be spent on the lowest cost pharmaceuticals. Another important measure would be to support public health research initiatives which focus on the diseases and needs of the poor – a field almost completely ignored by the major pharmaceutical companies. [93]

However, overarchingly the problem is the lens through which the IMF views economics and development. For as long as an unreconstructed IMF is seeking to control healthcare initiatives in poor countries or is implementing regulations such as wage-bill caps on publicly funded employment that are aimed at macro-economic stability but impact on healthcare, the poor in those countries will probably endure unacceptable healthcare outcomes.

If we are to retain the IMF as a separate institution, its world view needs to be transformed – a task so massive, one may doubt its achievability, but one that must be undertaken if we are to retain the organization. The IMF, as it functions today, is a fundamentalist organization. It is committed to market fundamentalism as that term is defined by Sparke in Chapter __ .** Market fundamentalism is a little like privatization – arguably sensible in a context of a well governed, efficient economy with strong institutions, such as the rule of law and courts, and a strong independent media, but a nonsense outside this institutional framework. Privatization, in a weak institutional context, will result in the sale of state-owned assets at a vast undervalue to those with political connections and resources as was seen in Russia in the 1990s. Likewise, leaving the provision of healthcare to the market is arguably sensible in a well-governed, affluent country with the capacity to monitor and regulate healthcare provision, but will further impoverish the poor in an already poor country without those capacities.

If we are to retain the IMF the challenge is for this institution to replace the lens through which it views the world and its own role in it. In the field of development, the IMF’s present perspective is disastrous.

[*] Professor, Faculty of Law, University of New South Wales; Australia21 Fellow ( see www.australia21.org.au); Senior Fellow, Tim Fischer Centre for Global Trade & Finance, Bond University. We would like to thank the participants at the Conference organised in Brisbane by Griffith University and the University of Aberystwyth in early September, 2007 for their helpful comments. All responsibility is ours.

[**] Research assistant.

[1] Article 12 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) recognises the “right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health”.

[2] Kimalu. Paul Kieti. “Debt Relief and Healthcare in Kenya.” Paper prepared for presentation at a Conference on Debt Relief and Poverty Reduction. Kenya Institute for Public Policy Research and Analysis ( July 24, 2001) at 2.

[3] Amartya Sen, “Global Doubts as Global Solutions”, Alfred Deakin Lecture, Melbourne, May 15, 2001, available at http://www.abc.net.au/rn/deakin/stories/s296978.htm

[4] Labonte, Ronald; Tor Gerson, Renee. “Interrogating globalization, health and development: Towards a comprehensive framework for research, policy and political action.” Critical Public Health. June 2005 15(2): 157-179 at 157.

[5] Id at 160.

[6] Id at 161.

[7] Ebrahim Malick Samba, “African Healthcare Systems: What Went Wrong”, Healthcare News, Dec 8, 2004 at 1.

[8] Buckley, Emerging Markets Debt, Kluwer Law International, London, 1999, chap 2; Woodroffe, Jessica & Ellis-Jones, Mark. “States of Unrest: Resistance to IMF Policies in Poor Countries.” World Development Movement Report. Global Policy Forum. (September 2000) at 2.

[9] Saori Ohkubo, “IMF Structural Adjustment.” The Public Politics Project. (1997) Towson University (9 March 2006).

[10] Ibid.

[11] Joseph E Stiglitz, Globalization and Its Discontents, Penguin, 2002; Susan George, A Fate Worse Than Debt, (New York: Grove Weidenfeld, 1990), at 143, 187, 235; Walden Bello, Dark Victory: The United States and Global Poverty, Pluto Press: London, 2nd edn., 1999.

[12] Asad Ismi. “Impoverishing a Continent: The World Bank and the IMF in Africa”, the Halifax Initiative Coalition, (July 2004) at 19.

[13] Diana Sanchez and Katherine Cash. “Reducing Poverty or repeating mistakes? A civil society critique of Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers.” Church of Sweden Aid, Diakonia, Save the Children Sweden and the Swedish Jubilee Network (December 2003) at 13.

[14] International Monetary Fund, Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSP) (2007) <http://www.imf.org/external/np/prsp/prsp.asp> at 6th August 2007.

[15] Frances Steward and Michael Wang. “Do PRSPs empower poor countries and disempower the World Band, or is it the other way round?” (Working Paper Number 108, QEH, October 2003) at 4.

[16] Sanchez and Cash, op cit n 13 at 13.

[17] Steward and Wang, op cit n 15 at 5.

[18] Sanchez and Cash, op cit n 13 at 13-14.

[19] Ricardo Gottschalk. “The Macroeconomic Policy Content of the PRSPs: How Much Pro-Growth, How much Pro-Poor?” The Institute of Development Studies. University of Sussex (February 2004) p 10-11.

[20] Sanchez and Cash, op cit n 13 at 9.

[21] Bos, Eduard R (ed). Disease and Mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa (2nd Edition). Herndon, VA: World Bank, 2006 at 18.

[22] Id at 19.

[23] Id at 20.

[24] Id at 7

[25] Id at 20.

[26] "World Development Report 2006: Equity and Development.” World Bank (2006) at 68.

[27] Bos, op cit n 21 at 12.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Id at 13.

[30] "World Development Report 2006: Equity and Development.” World Bank (2006) at 68.

[31] Bos, op cit n 21 at 12.

[32] M Turshen, “Privatising Health Services in Africa” New Brunswick Canada: Rutgers University Press (1999) at 11.

[33] P.A Kapoka. “Provision of Health Services in Tanzania in Twenty first Century: Lessons from the Past.” Presented at a work shop held by Dar es Salaam. International Federation of Catholic Universities (2000) at 11.

[34] Turshen, op cit n 32 at 11.

[35] K. Buse, & G. Walt, “An Unruly Melange? Coordinating External Resources to the Health Sector: A review. Social Science & Medicine 45 (3), 449-463 (1997).

[36] “Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper: the Second Progress Report, Tanzania 2001/02.” Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (2003). Dar es Salaam (March 2003).

[37] Id at 55.

[38] World Bank, “Beyond Scarcity: Power, Poverty and Global Water Crisis” in the Human Development Report, Washington, DC,: World Bank Publications, 2004 at 321.

[39] Ibid.

[40] “National Health Accounts for Uganda: Tracking Spending in the Health Sector – both public and private. Ministry of Health, Kampala, Uganda (2000) at 9.

[41] Turshen, op cit n 32.

[42] Central Intelligence Agency , World Fact Book, (2007).

[43] “Uganda Poverty Status Report (2003)” The Republic of Uganda Ministry of Finance (2003) at 24.

[44] Ibid.

[45] “WHO Country Cooperation Strategy: Uganda.” World Health Organisation (2005) at 7.

[46] Xu, Ke et al. “The Elimination of User Fees in Uganda: Impact on Utilization and Catastrophic Health Expenditures.” (Discussion Paper 4) World Health Organization (2005).

[47] Id at 16.

[48] Bank, World. African Development Indicators. Washington, DC, USA: World Bank Publications, 2004. p 320.

[49] Bos, op cit n 21 at 12.

[50] Asad Ismi. “Impoverishing a Continent: The World Bank and the IMF in Africa” the Halifax Initiative Coalition, (July 2004) at 16.

[51] International Monetary Fund, (2004) About the IMF, available from http://www.imf.org/external/about.htm.

[52] Joseph Stiglitz, (2002) Globalisation and its Discontents, New York: Norton Press, 15.

[53] The full text of the Purposes of the IMF can be found in Article I, Articles of Agreement of the International Monetary Fund, available from http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/aa/aa01.htm.

[54] Hetty Kovach. “Unable to Vote with One’s Feet? Developing Countries and the IMF.” Global Policy Forum. (March 2, 2006 ) at 2.

[55] Ibid.

[56] Possing Susanne. “Between Grassroots and Governments Civil Society Experiences with the PRSPs: A Study of Local Civil Society Response to the PRSPs.” Danish Institute for International Studies (DIIS Working Paper 2003:20) (September 2003) AT 7.

[57] George Dor. “G8, Tony Blair’s Commission for Africa and Debt.” Global Policy Forum (July 7, 2005) at 1

[58] Samba, op it n 7 at 3.

[59] Kovach, op cit n 54 at 1.

[60] Id at 2.

[61] Marek, T., Yamamoto, C., Ruster, J. Private Health: policy and regulatory options for private participation partnerships, Washington, DC: World Bank; 2003, cited in Pierre Unger. “Disintegrated care: the Achilles heel of international health policies in low and middle-income countries” International Journal of Integrated Care (18 Sept. 2006) at 5.

[62] Pierre Unger. “Disintegrated care: the Achilles heel of international health policies in low and middle-income countries” International Journal of Integrated Care, Sept. 2006 at 5; “Privatisation generally in Sub-Saharan Africa has failed on several counts”: Kate Bayliss and Terry McKinley, Privatising Basic Utilities in Sub-Saharan Africa: The MDG Impact; Accessed online via <http://www.undp-povertycentre.org/pub/IPCPolicyResearchBrief003.pdf> (1/05/2007).

[63] Unger, id at 4.

[64] Sreenivasan, Gauri & Grinspun, Ricardo. “Global Trade/Global Poverty: NGO Perspectives on Key Challenges for Canada -- Trade and Health: Focus on Access to Essential Medicines.” Canadian Council for International Co-operation Trade and Poverty Series (June 2002) at 2.

[65] Ibid.

[66] Samba, op it n 7 at 2.

[67] World Health Organization, Report of the Regional Director of Africa, “Poverty, Trade and Health: An Emerging Health Development Issue.” (June 17 2006) at 3.

[68] Labonte & Tor Gerson, op cit n 4 at 161.

[69] Mills A., “To contract or not to contract? Issues for low and middle income countries”, (1998) Health Policy and Planning,vol 13(1) at 32–40; and McPake B, Hongoro C., “Contracting out of clinical services in Zimbabwe”, (1995) Social Science and Medicine, vol 41(1) at 13–24.

[70] Unger, op cit n 62 at 7.

[71] Ibid.

[72] Ricardo Gottschalk. “The Macroeconomic Policy Content of the PRSPs: How Much Pro-Growth, How much Pro-Poor?” The Institute of Development Studies. University of Sussex (February 2004) at 3.

[73] Steward and Wang, op cit n 15 at 19.

[74] Sanchez and Cash, op cit n 13 at 10-11.

[75] Ibid.

[76] Kovach, op cit n 63 at at 1.

[77] Steward and Wang, op cit n 15 at 19.

[78] Nancy Alexander. “Poverty Reduction strategy Papers (PRSPs) and the Vision Problems of the International Financial Institutions (IFIs)” Citizens’ Network on Essential Services, Silver Spring, Maryland (January 2004) at 5.

[79] Woodroffe & Ellis-Jones, op cit n 8 at 2-3.

[80] Independent Evaluation Office of the IMF, “The IMF and Aid to Sub-Saharan Africa”, (IMF: 2007), available at http://www.imf.org/external/np/ieo/2007/ssa/eng/pdf/report.pdf, accessed on August 20, 2007

[81] Quotation is from the Foreward by Thomas A Bernes, Director, IEO, id at vii.

[82] IEO Report, id at 32.

[83] Center for Global Development, “Does the IMF Constrain Health Spending in Poor Countries? Evidence and an Agenda for Action”, available at http://www.cgdev.org/content/publications/detail/14103, accessed on August 20, 2007.

[84] Id at x.

[85] Id at xvi.

[86] Unger, op cit n 62 at 9.

[87] Alexander, op cit n 78 at 6.

[88] The Fund, the Bank and the World Trade Organisation all play important roles in global health governance.

[89] Chapter __ in this volume. **

[90] Chapter __ in this volume. **

[91] Sherry Poirier, “How ‘Inclusive’ Are the World Bank’s Poverty Reduction Strategies? An Analysis of Tanzania and Uganda’s health Sectors” Simon Fraser University (Thesis Paper) (2006).

[92] There is nothing new or novel about this proposition: Shultz, George, “Merge the IMF and World Bank”, (1998) International Economy, 12(1), 14; Burnham, James, “The IMF and World Bank: Time to merge” (1999) Washington Quarterly, 22(2), 101.

[93] Sreenivasan & Grinspun, op cit n 64 at 13.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/UNSWLRS/2008/14.html