University of New South Wales Faculty of Law Research Series

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Faculty of Law Research Series |

|

Last Updated: 23 August 2011

Working towards the resilient lawyer: early law school strategies

Prue Vines, University of New South Wales[♣]

Citation

This paper was presented at the First Year Experience Conference, Bond University, 2 July 2011. This paper may also be cited as [2011] UNSWLRS 30.

Abstract

We know that law students suffer disproportionate levels of depression compared with other students. This paper draws on research which suggests some possible reasons why and approaches to the development of resilience within the academic environment. It is argued that the resilient lawyer (one whose mind is well-furnished beyond the black letter law and whose understanding of self and ethical and other life problems has been developed) is a reasonable goal for law schools to keep in mind. In planning for the first year experience it is useful to keep this in mind and begin to bed down some of the skills and attitudes which are most likely to enhance the development of the resilient lawyer.

Introduction

In this paper I consider why law students suffer disproportionate levels of depression [1]compared with other students and the implications of this for the law school and particularly for early law school, which is the time when it appears that students begin to suffer these effects. Undergraduate law students begin to suffer depressive illness in quite high numbers within six to 12 months of beginning their studies.[2] How can we enhance our students’ resilience to reduce this toll on our students’ well-being. In the paper I discuss what it means to be resilient as a lawyer. I argue that the resilient lawyer has certain characteristics, some of which can be fostered by the law school without turning itself into a counselling service or a ‘nanny-lawschool’. This latter point I see as very important. I am aware that here I am preaching to the converted, but those who are not converted are very concerned that that may happen to them. An academic whose major focus is on their own career which probably means research needs a very good reason to be interested in the mental health of their students, preferably one which will enhance their own lives and research or at least not impede it. I sketch some strategies both within and outside the curriculum which seem to me legitimate, likely to be effective, and within the reasonable reach of law schools’ professed graduate attributes and TLO’s.[3]

Why do law students suffer disproportionate depression?

It is well known that western societies are suffering from an epidemic of depression generally, but lawyers and law students are disproportionately affected[4]. The dominant psychological theory of the aetiology of depression today is the theory of learned helplessness. This theory is based on research which has shown that patterns of thinking, or attributions, affect feelings of wellbeing. That is, that attributional style (that is, the way one thinks about cause and effect in one’s own life) is important for the development of depression. We also know that both inherent and learned personal characteristics can affect the likelihood of depression. There is a strong argument as well that western culture’s strong individualistic ethic and conception of the self as detached from its (social) context is a strong contributing factor to the rise of depression in the west.[5] (However I can’t fix that now...)

The dominant characteristics of depressed thinking include feelings of helplessness and loss of autonomy. Sheldon and his colleagues have produced empirical (and cross-cultural) data which suggests what psychological needs are required for a positive life experience.[6] The critical needs identified by that study include:

In our study of some 2,500 university students[7] we found that, at a statistically significant level, law students,( in contrast to all other students including those in medicine ) had the following characteristics:

In our article we argued that these characteristics were strongly related to some of the factors regarded as significant for predisposing to depression. In the list above I have marked them with one of the two major factors we think are significant for law schools to deal with. [8] For law students and the law academy autonomy and social connectedness are probably the most important issues, or at least the ones which will repay attention and may properly be in the province of the legal academy.

Martin Seligman, the doyen of positive psychology, says the elements of well-being are these:[9]

If we compare the two lists we see some strong similarities. Accomplishment and competence are very similar, self-esteem and positive emotion both seem to be products of other factors. Social relationships appear in both lists. Autonomy in the first list seems somewhat different from engagement and meaning in the second list. However, I think they have similarities, and I note that autonomy is particularly important in relation to preventing depression. The different focus of the other list, on well-being, means it is more broadly focused. It seems reasonable to continue to use the autonomy language while considering how the wider factors Seligman refers to might also contribute to the meaning and value of autonomy to law students and lawyers.

Autonomy as authenticity

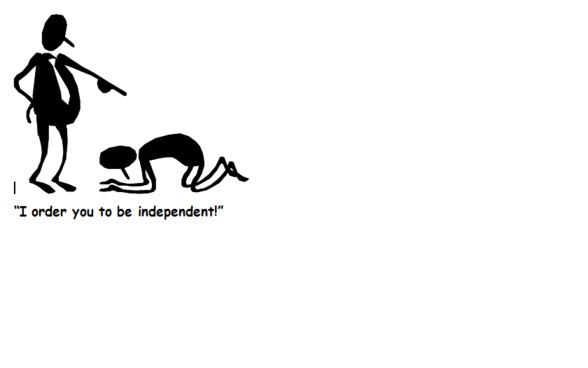

Autonomy is best thought of, I think, as Lawrence Krieger suggests, as ‘authenticity’. It does incorporate independence and the ability to take control of one’s life, but it is more. Indeed it goes to Seligman’s factors of meaning and engagement as well. Krieger’s view is that autonomy includes the ability to be true to one’s own genuine self and evaluate oneself.[10] People with autonomy are relatively unlikely to accept other people’s valuations nor are they likely to be motivated by external factors. Thus intrinsic interest is likely to be a marker of autonomy; a very high concern about grades (external assessment) is likely to mark a lack of autonomy etc. This should ring a very loud warning bell. We do not want to be in the situation where we paradoxically try to force people to be independent.

It is worth noting that the literature suggests that ethical

crises often precipitate depression in

lawyers[11]. I

suggest that part of the explanation for this is that the person may have had to

do something that cuts across or against that

authentic self. So I see this

also as an autonomy issue.

Social connectedness

Social connectedness is very important, but it needs connection with autonomy. This may be different from what some of our students experience, even with their families. If their only experience of relationships consists of being bossed about or seeing relationships as a means to an end rather than an end in itself (both of which seemed to appear quite strongly in our survey) then the protectiveness of social connectedness is lost. Competitiveness can also damage social connection if it goes too far.

Who or what is the resilient lawyer?

Resilience has been defined as ‘the individual’s belief in their personal control of how they will cope with adverse circumstances’[12] Reachout Australia says “Resilient individuals have personal strengths, skills and abilities which help buffer them against stress”.[13] The interconnected factors that the research suggests are particularly important for this are these:

A resilient lawyer is one who can deal with the tough issues that have to be handled in legal practice and come through the other side without breaking. One misapprehension that needs to be corrected is the idea that people break down because they are weak compared with others. Yes this is true to some extent, but the medical evidence is that enough stress can break anyone. The ability to think about the issues, recognise stress and deal with it using whatever tools one has, fall back on friends and family when necessary for support and maintain the sense of who one is will increase resilience. Note that in relation to ethics there are two ways to be resilient – first is to ignore ethics altogether, trample over people and just not care. This is practical but it is not the aim of legal education to produce such lawyers; and certainly the rules of court require ethical lawyers. The second, preferable way is to develop an ethical sense of one’s authentic self and be realistic about the issues to be faced. We need ethically resilient lawyers. [14]

Why should law schools be concerned with this?

Many legal academics are concerned at the swing towards thinking about the mental health of students. There are many reasons why they are right to be concerned. We are not counsellors; we are not specialists in mental health, and we should not see ourselves in those roles. However, we are concerned with our students’ minds. And we waste all our time when a bright student sinks and falls, taking with them all they’ve learned. As people who teach law to people who may or may not be lawyers our interest is in helping to shape people who benefit society through their understanding of the rule of law in the broadest sense, as well as the details of legal argument etc. The Council of Australian Law Deans has suggested that the mental health of law students might become one of the standards or goals of Law Schools: [15]

‘One must be cautious not to over-reach, but a possible articulation of the relevant sentiment might take the form of Standard 1.3.4:

‘The law school’s objectives include demonstrating a high regard for the mental wellbeing of its students and to improving their awareness of the stresses associated with legal education and practice and the means to manage them.’

Strategies within the academic environment for working towards the resilient lawyer

Here I simply sketch some ideas. Some are classic things which one would expect to exist within the curriculum. Others are things that might be provided or suggested and lie outside the usual curriculum.

The tools that should be used to help us deal with the ideas that follow include these:

Building autonomy

A number of strategies can go to building autonomy and indeed have been tested[16] in relation to the curriculum supporting autonomy in students means giving them some level of control. Obviously we probably know better what should be in the curriculum, so how is this possible. One of the easiest ways is to give as much choice as possible within the necessary confines – for example:

Obviously there cannot be unlimited choice. Sometimes one simply must decide. In that case the best approach seems to be to give a rationale which is real and which recognises the point of view of the students. For example, ‘I know this seems really boring and irrelevant to your lives, but if you can master this you can then go on to X topic or Y topic which you are really interested in, and which you won’t understand if you haven’t mastered this .‘ A properly reasoned rationale allows the person to feel that they would have chosen that course anyway or at least to feel persuaded.

Building Social connectedness

What should the role of the law school be in relation to social connectedness? To some extent this should be managed as a by-product of classes and social events. Student law society social events have a place in this. For teachers, students will get to know each other better doing groupwork than by listening en masse to a lecture. Facilitating students early on getting each other’s email addresses etc is easily done early in classes. Creating relationships through peer mentor programs which put senior students with small groups (2 senior students with 8 first years seems to be a good model) seems to automatically create some friendships when everyone is new. Modeling sincere friendly and respectful behaviour while teaching; and being straightforward and honest in our dealings with students goes a long way. I don’t think it is our role to create friendships. But we can give connections between people some space and we can make sure we don’t foster treating relationships as mere means to ends by talking about networking purely as a way of getting jobs and so on. The study we carried out showed amongst law students a stronger tendency to think about relationships this way than any other groups

The following suggestions concern building resilience through autonomy and social connectedness and other matters:

Ethical sense of authentic self

It is relatively easy to present students with realistic ethical dilemmas, building from plagiarism treated as an ethical problem up to significant professional ethical dilemmas such as your boss requiring you to do something repugnant where you have to weigh up your need to have a job against your ethical standards. Giving realistic scenarios for role plays allows students to practice what they might come up against. Discussing them in class helps students to develop a ‘grammar’ for discussing such dilemmas. This can be done not only in Legal Ethics courses, but also in torts or contracts or property courses.[17]

The literature suggests that people who choose law for themselves (rather than because their parents told them to do it or they got the marks) do so because their personality type is more likely to be a ‘helper’ type. These are the students who want to fight for justice; they are also the ones who are most discomfited by ethical dilemmas. I suggest to you that these are the ones we really want to be practising as lawyers. The importance of building their sense of authentic self with a grammar for discussing ethical issues is vital for them. For the others, that ethical sense may need to be awakened in some way, although young people are very often extremely idealistic. When we can harness that idealism to a practical ethical understanding we have the best chance of developing the kind of lawyers I believe our society needs. If the aim is resilience, though, it is important that the students do not get the Hollywood version of ethics - the pie in the sky, it will all come right in the end and we’ll live happily ever after version. The reality is that ethical problems can bite deep, and they can take away one’s livelihood.

Downplaying marks

Marks for assessment are very important as a guide to how one is going. But hyper-competitive students may be so competitive because their motivation is external rather than intrinsic. I do not suggest the abolition of marks. But I do suggest discussion (in our Law School we train our student mentors to do this) of the importance of seeing marks for what they are rather than as the indicator of one’s worth as a person. To use the marks to compare with one’s own previous performance is very useful. To use the marks to gauge how much one has learned is also useful. But using them to assess whether one is more valuable as a person than someone else is not. That approach damages social connection as well.

The well-furnished mind

Developing resilience might be thought of as a developing the ability to bounce back. And what bounces back best is a ‘well-rounded’ ball. Encouraging students to develop a well-furnished mind is an important part of developing intellectual resilience. This means reading beyond the black letter law; reading literature; watching films; getting to know the heroes of our law – the people who have dealt with ethical dilemmas at great cost to themselves or have appeared for other people at great cost to themselves. The more well-furnished the mind the greater the range of comparators and resources available to handle whatever life throws at us. What we can do is suggest resources (beyond the curriculum) that might enhance our law students’ understanding of law and life and their connections with each other.

The direct approach to resilience

One way to enhance resilience is to directly discuss how to enhance it. We have a website for current students which does this. The website is not just about what can go wrong; it is about enhancing and enriching one’s life as a law student. It carries a frank discussion of what to do when things go wrong, but also strategies which we know enhance well-being, including the absolute basics – eat, sleep, exercise - as well as music, law and literature, movies.

Normalising asking for help

There is considerable evidence that law students are reluctant to ask for help when things go wrong. They are very bright and they usually think they should fix themselves. Also their competitiveness means they may be afraid of appearing weak. Normalising the process of asking for help is a really important factor in catching problems early. In my law school again we train our peer mentors for first years to do this by teaching them to casually mention that people often have trouble, but that you just ask for help and then it gets sorted. I also get teachers in first year to do this. Because I am seeking the normalising of this I try not to make a big deal about it. This is not presented as a big thing: it is presented as a remark ‘by the way’ a couple of times in the semester by both first year teachers and peer mentors.

Fighting the summer clerkship war

Summer clerkship programs in my opinion are pernicious and deeply damaging to students. If we must have these programs I would argue we should also have strong mentoring relationships set up in the year before this process happens. I think such mentoring should move students to see that summer clerkships and ultimately large firm practice only suits some people and should not be seen as the pinnacle of legal practice; that other forms of legal practice are equally valuable and may suit some people a great deal better, and that the over-emphasis on getting into summer clerkships is really a form of snobbery. This is not a popular view because these firms give money to student law societies and to law schools. The damage is rarely recognised.

Conclusion

I hope that this paper has demonstrated that enhancing resilience in our students is more likely to be achieved through very many small initiatives, carried out repeatedly, than by one or two large ones. Much of this needs to be carried out through attitudinal change which needs to take place amongst academics as well as amongst the students we deal with. (It is of course true that legal academics are also subject to depression and also need resilience). Law Schools can achieve this without enormous stress on budget or staff and the goal of enhancing our students’ resilience is worth working towards.

[♣] Professor,

Faculty of Law, University of New South

Wales

[1] Australian

research confirms the pattern seen in American research(see note 3 below):

Beaton Consulting, Annual Professions Survey 2007: Short

Report (2007); Norm Kelk, Georgina Luscome, Sharon Medlow and Ian Hickie,

Courting the Blues: Attitudes Towards Depression in Australian Law Students

and Legal Practitioners’

(2009),

[2] Ann

Iijima, ‘Lessons Learned: Legal Education and Law Student

Dysfunction’ (1998) 48(4) Journal of Legal Education

524.

[3] See ALTC

/CALD Report on Learning and Teaching in the Discipline of Law,

2009

[4] William

Eaton , et al, ‘Occupations and the Prevalence of Major Depressive

Disorder’ (1990) 32 Journal of Occupational Medicine 1079,1083; G

Andrew Benjamin, Elaine Darling and Bruce Sales ‘The Prevalence of

Depression. Alcohol Abuse and Cocaine Abuse

among United States Lawyers’

(1990) 13 International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 233, 240; Martin

Seligman, Paul Verkuil and Terry Kang, ‘Why Lawyers are Unhappy’

[2005] DeakinLawRw 1; (2005) 10 Deakin Law Review 1, 5; Martin Seligman, Authentic

Happiness (2004) 177; and see generally American Bar Association, At the

Breaking Point: the Report of a National Conference on the Emerging Crisis in

the Quality of Lawyers’ Health and Lives

–Its Impact on Law Firms

and Client Services

(1991).

[5] See Pam

Stavropoulos Living Under Liberalism: the politics of depression in Western

Democracies, Universal Publishers, Boca 2008. Note that this is not to say

that individualism itself is necessarily problematic, only when it

completely

separates (alienates) the individual from others. Completely subordinating the

individual to the collective is also problematic

for mental health.

[6] Kennon Sheldon,

et al, ‘What is Satisfying about Satisfying Events? Testing 10 Candidate

Psychological Needs’ (2001)

80 Journal of Personality & Social

Psychology

325.

[7]

Massimiliano Tani and Prue Vines ‘Law Students Attitudes to Learning: a

pointer to depression in the legal academy and the

profession?’ [2009] LegEdRev 2; (2009)

19(1) Legal Education Review

3-39

[8] We think

that Law Schools always deal with competence, and that self esteem is so

all-pervasive that it is outside the remit of law

schools. Similarly security is

not an issue law schools can deal with. That leaves autonomy and social

connectedness as factors law

schools might do something about.

[9] Martin

Seligman, Flourish: a visionary new understanding of happiness and

well-being, Heinemann Australia, 2011 p

16.

[10] Lawrence S

Krieger, ‘Institutional Denial about the Dark Side of Law School, and

Fresh Empirical Guidance for Constructively

Breaking the Silence’ (2002)

52 Journal of Legal Education 112,

119

[11] Krieger,

L. S. (2005). The hidden sources of law school stress: Avoiding the mistakes

that create unhappy and unprofessional lawyers.

Tallahassee.

[12]

Vicki Bitsika, Christopher F. Sharpley, Kylie Peters ‘How is resilience

associated with anxiety and depression?’ (2010) 13 German J

Psychiatry 9-16 at

10.

[13]

http://au.reachout.com/find/issues/mental-health-difficulties

[14]

Colin James has argued this comprehensively: article in (2008) The Law

Teacher

[15] G

Davis and S Owens, ALTC/CALD Project: Learning and Teaching in the

Discipline of Law 2009 at

136

[16] Kennon M.

Sheldon and Lawrence S. Krieger, ‘Understanding the Negative Effects of

Legal Education on Law Students: A Longitudinal

Test of Self-Determination

Theory’ (2007) 33 Pers Soc Psychol Bull

883

[17] Michael

Robertson, ‘Providing Ethics Learning Opportunities throughout the Legal

Curriculum’ (2009) 12(1) Legal Ethics 59.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/UNSWLRS/2011/30.html