University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

ANDREW LYNCH[*]

In providing a reflective comment upon the High Court’s constitutional law decisions of a single calendar year – that of 2001[1] – Stephen Gageler acknowledged that to do so was largely to adopt an American tradition found within the pages of the Harvard Law Review for over half a century now.[2] But, as he said, in the beginning there were the statistics. The American commentary on the Supreme Court’s term began its life as a foreword to the presentation of tables and charts indicating ‘some of the more significant features of the Court’s activity’[3] across that period.

The practice of critiquing recent developments in constitutional law, albeit through the lens of a particular year, is one which we can adopt without much difficulty.[4] The work of the High Court of Australia in this field is already subject to a healthy amount of analysis – a steady stream in fact – from the profession, academia and, to some extent, the media. Australian lawyers have, however, been largely reticent about the use of empirical studies as a means of appreciating the dimensions of judicial work.[5] Not for us, the number crunching of jurimetrics – or even a simple curiosity in raw data. As a result, a custom of annually producing statistical information about the High Court may be harder to develop.

This article aims to redress that deficiency through the presentation of tables quantifying various features of the High Court’s recent work, with particular emphasis upon its constitutional law decisions. There is, however, a difficulty for the empiricist in that the case law to be garnered from a single year would be too small a sample from which to observe any significant patterns and trends. The solution arrived at has been to abandon that constraint – instead, this paper concerns the almost five years from Chief Justice Gleeson’s arrival at the High Court in May 1998 until the retirement of Gaudron J on 10 February 2003. As such, it represents a snapshot of the Court’s handling of constitutional matters over recent years which aims to helpfully supplement more traditional forms of analysis of the same material.

Before considering the statistics themselves and explaining the means by which they were compiled, some comment upon the practice and purpose of this kind of work may be helpful.

The Harvard Law Review’s employment of statistical analysis did not suddenly emerge of its own accord with the 1949 volume’s review of the Supreme Court’s 1948 term.[6] Seemingly the impetus for this development lay in the success of an earlier series of articles by then Professor Felix Frankfurter in co-authorship with various others.[7] The Frankfurter articles provided statistics from the Court’s 1928 term but broke off when their chief author was appointed to the subject of his study and continuation of the series would have been, presumably, slightly unseemly.[8] When the student editors of the Harvard Law Review revived the practice ten years later, they owed a debt to those earlier works for the example set.[9] This debt extended to the editors’ apparent belief that, following on from Frankfurter and company’s earlier work, they could simply present the tables of data with only fairly minimal explanation as to their purpose, let alone method of compilation. The editors of the 1961 volume attempted to remedy these deficiencies through greater detail on both scores,[10] but in the 1968 volume the editors provided further practical detail after making the following admission:

Growing concern in recent years over the accuracy of some of the tables – primarily those which attempt to classify cases by subject matter – has led to suggestions that part or all of the enterprise be substantially revised, if not completely abandoned. At a minimum, it was felt, the nature of the errors likely to be committed in constructing the tables should be indicated so that the reader might assess for himself the accuracy and value of the information conveyed.[11]

Thus qualified, the tables have survived. As a quantitative method tried, tested and occasionally modified for over fifty years, they obviously hold enormous sway over researchers attempting to perform similar work in other jurisdictions. Of course, a straight application of the Harvard Law Review’s rules of statistical compilation to the practice of the High Court of Australia is not possible. Account must be taken of the different practices and procedures between this institution and that of the United States Supreme Court, and the rules adapted accordingly.[12] But it should be acknowledged at the outset that much of the methodology employed in preparing this paper is influenced by that which is used year in, year out by the Harvard Law Review.

What is the purpose or value of empirical research? As distinct from the reasoning contained in the Court’s opinions – quite often elusive and subject to competing interpretations by commentators – statistics appear to provide certainty, at least in answering questions of a particular nature: How many cases have been decided over a period? On which areas of law? What is the level of agreement across the Bench on various issues? What is the propensity of the Bench to unanimity? Is there any regular pattern of voting amongst the justices of the Court on certain issues? Which justices dissent more frequently than others?

The importance of discovering such information lies in how it may assist us to appreciate the way in which the work of the Court is performed, and the complexity of the legal controversies which face it. This feeds in to more familiar scholarship about the Court, and the legal reasoning of its members. For example, an awareness of the number of cases decided over a period may well be relevant to those examining the efficiency of the institution’s procedures or the adequacy of its resourcing. A breakdown of those cases by topic may illuminate which areas of the law are in a state of instability or change at any given time. This information would certainly be supplemented by indications as to which issues tend to fragment the bench, and the degree of such disagreement. Strong evidence of regular voting blocs or alignments may point to the security of any particular view from being overthrown in the foreseeable future. And lastly, statistics on dissent may well attest to a marked difference in methodology or ideology amongst the justices which is ripe for scrutiny and comment by outsiders.

It is, of course, possible to discuss all of these sorts of matters without any reliance upon statistical research and, on the whole, I would agree that Australian legal scholarship has not suffered unduly for the absence. So keenly is the Court observed that I suspect we appreciate intuitively much of what is to be confirmed empirically. That is not to say, however, that basic data about the High Court and its judges would not further enhance or support many of the arguments and hypotheses which are regularly aired in academic journals. In many instances, it would. Also, there remains not just simple validation of our opinions and perceptions, but the potential for new avenues of research to be illuminated by statistical information.

Lastly, it is appropriate to acknowledge the limitations which inhere in empirical work and the need for it to exist in relation to, and be supported by, more qualitative analysis. For this reason, I would endorse the advice of the Harvard Law Review editors when they cautioned the wary that their tables ‘are not an end in themselves but are intended to present a foundation for more detailed consideration’.[13] Because the compilation of statistics requires the consistent application of a reasonably rigid methodology it is inevitable that the figures produced may, by themselves, present an overly simplistic picture.[14] It certainly will not be the whole picture. There are a number of useful counters to this. One is to design a justifiable methodology which is well suited to the material under examination.[15] Another is then to be explicit about those instances where distorting effects are inevitably produced by application of the methodology to particular sorts of cases. Additionally, accumulating even the very basic statistical information which I am aiming to present here poses occasional problems of complexity requiring the exercise of discretion.[16] The choices made by the researcher should be flagged so that others may be aware of the degree of subjectivity employed in the study’s completion. In these ways, the inevitable shortcomings of any one particular approach and the results produced are made apparent. This does not diminish the usefulness of such research – rather, such transparency ensures that reliance upon it is well informed and reinforces the notion that quantitative studies should not stand alone, but be used in conjunction with complementary scholarship of a more discursive character.

In preparing statistics on the Gleeson Court’s work pertaining to constitutional law over the last five years, essentially one is rarely called upon to do anything more complicated than tally as one goes through the relevant reports.[17] However, the simplicity of much of this activity is underpinned by consistent application of a fixed classificatory system. It is necessary to briefly highlight the key features of the method adopted.

Although recent empirical studies of the High Court have all used the Commonwealth Law Reports (‘CLRs’) as the source for their data,[18] two considerations led to my use of the unauthorised Australian Law Reports (‘ALRs’) for this research. Firstly, the ALRs commended themselves by virtue of the speed with which they are produced relative to the CLRs. In order to ensure that as much of the entire sample period had been reported and so diminish, as much as possible, reliance upon electronic resources, the series quickest to print was always going to be preferred.[19] Secondly, although certainly every constitutional law case from the period is reported in the CLRs, the authorised series is not as comprehensive as the ALRs with respect to other matters. As shall be seen, this was important so as to allow consideration of the constitutional cases against the totality of the Court’s opinions over the period.

The timeframe for this study commences, appropriately enough, on 22 May 1998 with the appointment of Murray Gleeson as Chief Justice of the High Court. The stability in the Court’s composition from that time until Justice Gaudron’s departure on 10 February 2003 presents us with what is known as a ‘natural court’ and one which is of a suitably long duration.[20] A ‘natural court’ is a court ‘where the same Justices interact for the whole research period’.[21] With the appointment of Heydon J, a new ‘natural court’ of the Gleeson era effectively comes into being.[22]

Consequently, reports of cases heard prior to the Chief Justice’s arrival, even if judgment was delivered subsequently, are not tallied. For example, the decision in Chappel v Hart[23] was handed down on 2 September 1998, but as the case was heard in November 1997, it must be seen to predate the formation of the Gleeson Court. This is the only instance where the hearing date of the matter is invested with any significance – and it is for the purpose of exclusion. Otherwise, cases are organised into years on the basis of when judgment was delivered.[24] But in order that the significance of the five 2003 cases handed down before Justice Gaudron’s retirement may be sensibly contextualised, the 2002 results reach over to include those of early February 2003.

Tallying of cases for the entire period involved drawing on the reports found within volumes 156 to 194(1) of the ALRs. The final High Court case found in that series was handed down on 5 December 2002, leaving only ten eligible cases

of the relevant period unreported. These cases have still been included in the study, using the judgments posted on the AustLI webpages.[25]

All High Court cases reported in the ALRs across this period were tallied in order to provide some broader context against which to examine the Court’s constitutional work. This included any report where written reasons were recorded – including those involving an application for special leave.

Excluded from the study were reports of single judge decisions of the High Court. The only reported decision which requires further comment here is that of Hancock Family Memorial Foundation Ltd v Porteous,[26] which was a brief two judge decision (McHugh and Gummow JJ) denying special leave. This has not been included either. One of the advantages of considering the control sample is that it is certainly a larger pool of cases from which to draw statistics. Although this paper is focussing particularly upon constitutional cases, it is admitted that, for some purposes,[27] cases within that niche are not of such a quantity as to form a large enough group for analysis. Nevertheless, they are all that emanates from the natural court under examination. To some extent, concerns about drawing conclusions from an analysis of just those constitutional cases may be allayed by looking for similar trends in the total sample which may provide corroboration.

In identifying ‘constitutional cases’ as a group within the total sample, I have essentially adopted Stephen Gageler’s definition as being

that subset of cases decided by the High Court in the application of legal principle identified by the Court as being derived from the Australian Constitution. That definition is framed deliberately to take in a wider category of cases than those simply involving matters within the constitutional description of ‘a matter arising under this Constitution or involving its interpretation’.[28]

But additionally, I have widened the net so as to include cases which involved questions of state constitutional law of which there were but three out of the total of 62.[29]

The catchwords appearing in the headnotes of the ALRs indicate the involvement of constitutional issues and have been relied upon for classification. Admittedly, the degree to which constitutional questions were central to the resolution of these cases varied. But wherever constitutional principle arose, regardless of the dominance of other legal questions, the case was included in the core group under analysis.[30] In some instances the descriptors chosen by the reporters do not necessarily reflect the constitutional point for which the case has become significant, but instead focus on other constitutional considerations.[31] While this may have undesirable warping effects (particularly in Table C which aims to represent the subject matter of constitutional litigation in the High Court over the five years), classification in this way has the advantage of being objective, transparent and replicable by other scholars.

The central purpose in compiling these statistics has been to quantify the number of unanimous judgments, concurrences and dissents delivered by the Court and its members in the last five years. Although it may seem superfluous to explain these terms, some basic definitional clarity is essential if anything is to be gleaned from the figures themselves. This may be briefly done through the statement of three core rules which governed this exercise.

(a) A separately-authored statement of opinion as to how a case should be resolved is recorded as a separate judgment (concurring or dissenting) regardless of whether reasons are given or not.

For the purposes of tallying, unanimity has only been recorded when all sitting justices deliver the one written opinion. A decision may be unanimous through the conglomeration of separate concurrences, but unless there is a single opinion signed-off on by the entire Court, no unanimous judgment is recorded here. This is at variance with other empirical studies which tend to regard a separate judgment that does no more than indicate agreement with the opinion of another

(‘I concur’ is the classic example) as de facto co-authorship of the judgment agreed with. Indeed the Harvard Law Review has long adopted this approach.[32] I have indicated a preference elsewhere for resisting this trend where it is not useful for the particular purposes of the research[33] – as it is, for example, in Russell Smyth’s recent work on the identification of coalition voting blocs in the High Court.[34] My position is that unanimous or joint judgments require actual co-authorship and this may be contrasted with the situation where, despite apparent total agreement (though Coper warns against assuming this)[35] a justice speaks for himself or herself, regardless of the brevity. In this context, it seems best to recognise such concurrences for what they are: matters of substance duly acknowledged, it is clear that what has been delivered is most accurately regarded as a separate, concurring judgment.[36]

(b) A justice is considered to have dissented when he or she voted to dispose of the case in any manner different from the final orders issued by the Court.[37]

Like the preceding rule, this is a slight – albeit important – modification of the Harvard Law Review method. Those rules talk not of ‘final orders’ but ‘the majority of the Court’[38] – indicating the relative ease with which majorities have traditionally been identified in the United States Supreme Court.[39] However, identification of a majority can be a less certain exercise in respect of a court which issues opinions in seriatim. Not only does the Court as an institution not have a judgment written for it – there is the increased likelihood that there may not even be a majority of justices in favour of one particular result. The lack of a clear majority is an accepted incident of our judicial method – the final orders will reflect varying points of consensus amongst the judgments, but not necessarily the orders favoured by any readily discernible majority of the Bench, or even those of any one justice.

It would be a mistake to use the absence of an identifiable majority as a censure on the finding of a dissent – in such cases, the Court as an institution still states a result, albeit reached by composite. Instead, to enable the noting of dissent without the assistance of a majority opinion issued ‘for the Court’ as a counterpoint, dissension in judicial bodies giving seriatim opinions should be classified as disagreement with the orders issued by the Court. Indeed, this is demanded by the standard definition of dissent, which places more emphasis upon the relationship between a dissenting judgment and the orders made by the court as an institution than the differences in reasoning across the presiding judicial officers.[40] It is the former which is determinative of the judgment’s status, even though the latter is obviously instrumental in the creation of that institutional position.

The second thing to note here is the insistence that disposition of the case in any manner different from the final orders results in a judgment being tallied as dissenting. This is a direct derivation from the rules applied by the Harvard Law Review which also sees fit to add that ‘opinions concurring in part and dissenting in part are counted as dissents’.[41] I have outlined elsewhere the distorting effect which the strictness of this approach may have in particular cases by magnifying the true extent of disagreement in the Court,[42] but this is the inescapable by-product of the need to insist upon clear and consistent application of these concepts in order to produce a statistical picture. As said earlier, an awareness of that limitation and a willingness to supplement the quantitative results through a more considered analysis of the substance of the opinions are the only ways to offset the traditional deficiencies of this sort of work.

(c) Opinions that concur in the orders of the Court, even if not belonging to any actual majority, are not dissenting.

This rule really just serves as a corollary to the last one. Having denounced the notion of ‘majority’ as unhelpful in indicating dissent in courts which deliver judgments in seriatim and replaced in its stead the yardstick of the Court’s final orders, it seems worth pointing out the surprising results which may accrue. Of the seven justices in any case, there may be fewer in favour of the final orders than are opposed (either in whole or part) – in which case the number of dissenters exceeds those who concur in the Court’s result. The classic example of this is the 3:3:1 split in the decision of Dennis Hotels Pty Ltd v Victoria,[43] wherein only Menzies J concurs completely with the result which the Court reached as an institution. The irony is well appreciated – his Honour’s view of the matter as a whole clearly appeals to none of the other justices, yet its reflection in the Court’s order leads to a classification of the other six opinions as dissenting. As Kadzielski and Kunda have said of this phenomenon, ‘although this may be somewhat unrealistic, the totals [tallied] do reflect the number of judges who, over the course of the year, deviated from the actual legal decisions which were produced by the courts considered as units’.[44]

However, to put this unusual (though I would stress not illogical) consequence into some kind of perspective, I should add that only one matter from the period under examination displayed this feature.[45]

TABLE A (I) – ALL HIGH COURT OF AUSTRALIA CASES REPORTED FOR PERIOD

|

|

1998

|

1999

|

2000

|

2001

|

2002–03

|

TOTAL

|

|

Unanimous

|

2

(15.3%)

|

12

(17.6%)

|

5

(10.0%)

|

11

(16.6%)

|

6

(9.3%)

|

36

(13.7%)

|

|

By

Concurrence

|

6

(46.1%)

|

16

(23.5%)

|

22

(44.0%)

|

22

(33.3%)

|

26

(40.6%)

|

92

(35.2%)

|

|

Majority

Over Dissent

|

5

(38.4%)

|

40

(58.8%)

|

23

(46.0%)

|

33

(50.0%)

|

32

(50.0%)

|

133

(50.9%)

|

|

TOTAL

|

13

(100%)

|

68

(100%)

|

50

(100%)

|

66

(100%)

|

64

(100%)

|

261

(100%)

|

Table A (I) displays the extent of the High Court’s case load over the sample period and indicates how individual matters were resolved by the Bench. As indicated above, the purpose of preparing statistics on all the Court’s work is to enable some point of comparison in respect of how it responds to constitutional problems. Of the total 261 matters tallied for the Court, half were split decisions whilst the other half were determined without dissent. A unanimous opinion was written in almost 15 per cent of these cases.

Some explanation of the columns in the above table is necessary. Given the Chief Justice’s arrival in late May 1998 and the exclusion of decisions which predate his arrival, it is unsurprising that the column for that year features fewer cases than the others. Although the sample from that year is undeniably small, it probably still warrants separate presentation – if only so as to avoid inflation of the figures for 1999. The same cannot be said of the cases delivered by the Court in 2003 but before Justice Gaudron’s departure. There seems little to be gained by presenting these in isolation and so they have been absorbed into the statistics for 2002. Similar considerations guide the structure of the following table.

TABLE A (II) – ALL CONSTITUTIONAL CASES REPORTED FOR PERIOD

|

|

1998

|

1999

|

2000

|

2001

|

2002–03

|

TOTAL

|

|

Unanimous

|

1

(33.3%)

|

2

(10.0%)

|

1

(6.2%)

|

1

(10.0%)

|

0

(0.0%)

|

5

(8.0%)

|

|

By

Concurrence

|

1

(33.3%)

|

3

(15.0%)

|

8

(50.0%)

|

4

(40.0%)

|

7

(53.8%)

|

23

(37.0%)

|

|

Majority

Over Dissent

|

1

(33.3%)

|

15

(75.0%)

|

7

(43.7%)

|

5

(50.0%)

|

6

(46.1%)

|

34

(54.8%)

|

|

TOTAL

|

3

(100%)

|

20

(100%)

|

16

(100%)

|

10

(100%)

|

13

(100%)

|

62

(100%)

|

With Table A (II) we turn to the central topic under examination – the Gleeson Court on constitutional law. At a total of 62 cases, the Court’s constitutional work over the period represents close to a quarter of its entire load. Even so, in respect of individual years, I suspect the number of cases is just too few to make any particularly firm conclusions. The proportion of decisions resolved over a dissenting minority has increased, but admittedly not by as much as we might have anticipated given the lesser significance of precedent as a constraint in this context. To the extent that dissension is greater in such matters, it appears to impact more potently upon the likelihood of unanimity rather than just agreement per se.

Table B indicates the resolution of these constitutional cases in closer detail:

TABLE B – CONSTITUTIONAL CASES – HOW RESOLVED[46]

|

Size of Bench

|

Number of Cases

|

How Resolved

|

Frequency

|

|

7

|

43

(69.3%)

|

Unanimous

|

1 (1.6%)

|

|

By concurrence

|

18 (29.0%)

|

||

|

6:1

|

10 (16.1%)

|

||

|

5:2

|

8 (12.9%)

|

||

|

4:3

|

6 (9.6%)

|

||

|

|

|||

|

6

|

14

(22.5%)

|

Unanimous

|

1 (1.6%)

|

|

By concurrence

|

3 (4.8%)

|

||

|

5:1

|

8 (12.9%)

|

||

|

4:2

|

2 (3.2%)

|

||

|

3:3

|

0 (0%)

|

||

|

|

|||

|

5

|

4

(6.4%)

|

Unanimous

|

2 (3.2%)

|

|

By concurrence

|

2 (3.2%)

|

||

|

4:1

|

0 (0.0%)

|

||

|

3:2

|

0 (0.0%)

|

||

|

|

|||

|

3

|

1

(1.6%)

|

Unanimous

|

1 (1.6%)

|

|

By concurrence

|

0 (0.0%)

|

||

|

2:1

|

0 (0.0%)

|

||

Unsurprisingly, the bulk of the constitutional cases were heard by a bench comprising all serving justices, though the number of six-member benches is not insignificant. Despite the complete absence of dissent in the remaining categories of five and three-member courts, these are so few as to be relatively inconsequential.[47] So far as any clues as to dissent being evidence of the marginalisation of an individual justice, we can see a sizeable percentage of 6:1 and 5:1 decisions in the first two categories. But this is not especially notable in respect of seven-member benches which showed a propensity to split in diverse ways. It is more noticeable for the six-member benches, over half of which saw a minority of one. It is striking that only one constitutional case over the almost five year period produced a joint judgment from all seven members of the Court.[48]

Table C is the final one dealing with the Court as an institution before we move to consider the actions of its individual members. The purpose here is simply to indicate the nature of the constitutional matters which have been before the Court over the sample period. The standout group is what I have grouped together as ‘Federal Jurisdiction/Judicial Power/Ch III’. I concede that this is a somewhat clumsy categorisation, but I cannot quite conceive another moniker that could so briefly convey the essential themes of these cases, which seem to return again and again to the same concepts and words in Chapter III of the Commonwealth Constitution. It will be noted that the table weeds out the s 80 cases from the tangle that otherwise appears to sprout from this source, but even those are comparatively frequent. Altogether, roughly half the High Court’s constitutional work since the Gleeson appointment has involved what Leslie Zines memorably described as ‘the doctrinal basket weaving that Chapter III has generated’.[49] The presence of inconsistency matters in second place in Table C, below, is rather deceptive as four of the seven cases under that topic appear under alternative topic listings, and probably derive their substantive character from elsewhere than s 109. Of the other topics which are not simply one-offs, I do not think there are any surprises. Questions of the place of the Territories, acquisition of property and the implied freedom of speech have all been prominent over the last decade. It would have been more surprising had any of these topics not been represented. But even their relative rarity when contrasted with the domination of questions of judicial power is perhaps somewhat unexpected.

TABLE C – SUBJECT MATTER OF CONSTITUTIONAL CASES[50]

|

Topic

|

No of

Cases

|

References to Cases

|

|

Federal

Jurisdiction/Judicial

Power/Ch III

|

22

|

(156/563); (159/108); (161/318); (162/1);

(163/270); (163/576); (163/648); (165/171);

(168/616); (172/39); (172/366); (173/619);

(176/219); (176/545); (176/644); (177/329);

(183/645); (187/409); (188/1); (191/543);

(192/217); [2003] HCA 2

|

|

Inconsistency of Laws –

|

7

|

(161/318); (161/489); (163/501); (164/520);

(166/258); (169/607); (1 76/545)

|

|

Right to Trial by Jury –

|

6

|

(1 64/520); (166/159); (166/545); (175/338);

(180/301); (185/111)

|

|

Territories

|

4

|

(161/318); (1 65/1 71); (168/86); (191/1)

|

|

3

|

(160/638); (167/392); (176/449)

|

|

|

3

|

(182/657); (193/37); [2003] HCA 2*

|

|

|

Cross-Vesting of Power

|

2

|

(1 63/270); (171/155)

|

|

Implied Right to Freedom

of Expression

|

2

|

(185/1); [2002] HCA 57†

|

|

Sovereignty

|

2

|

(163/648); (184/113)

|

|

State Parliament

(powers of)

|

2

|

(158/527); (189/161)

|

|

1

|

(167/392)

|

|

|

1

|

(170/111)

|

|

|

1

|

(172/257)

|

|

|

1

|

(187/529)

|

|

|

1

|

(1 82/65 7)

|

|

|

1

|

(1 63/501)

|

|

|

1

|

(181/371)

|

|

|

1

|

(188/241)

|

|

|

1

|

(172/625)

|

|

|

Right of Citizen to Resist

Expulsion

|

1

|

(170/659)

|

|

State Acquisition of

Property

|

1

|

(177/436)

|

|

Common Law and the

|

1

|

(168/8)

|

|

Appointment of Senator to

Vacancy

|

1

|

(167/105)

|

|

Federal Implication

Limiting Commonwealth

Legislative Power

|

1

|

* At the time of writing, the case of Plaintif S157/2002 v Commonwealth [2003] HCA 2 is yet to be reported in the Australian Law Reports.

† At the time of writing, the case of Roberts v Bass [2002] HCA 57 is yet to be reported in the Australian Law Reports.

‡ At the time of writing, the case of Austin v Commonwealth [2003] HCA 3 is yet to be reported in the Australian Law Reports.

B The Gleeson Court’s Casework – The Individual Perspective

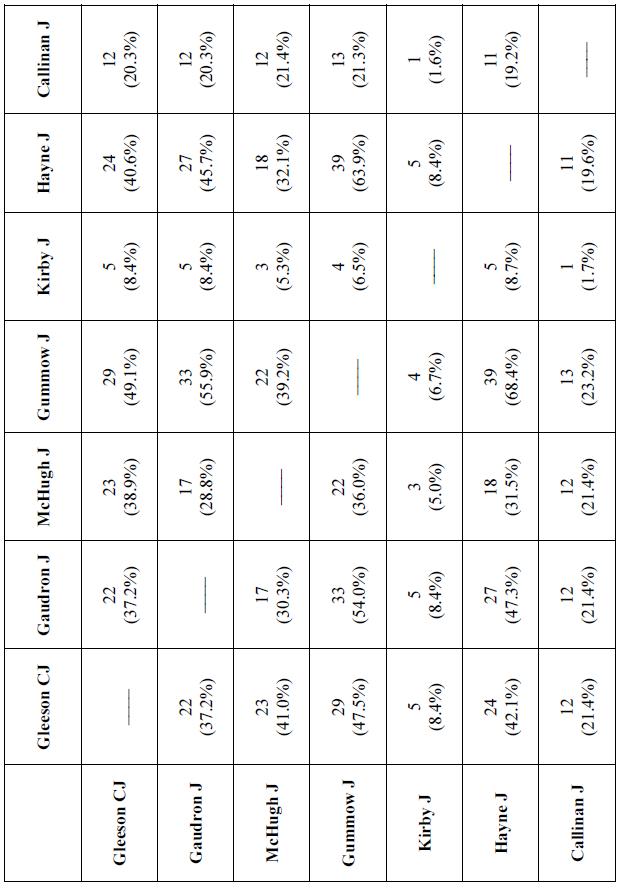

The following tables aim to indicate some of the actions of individual High Court justices over the period. Tables D (I) and (II) may be seen as further investigation of what was examined in Tables A (I), A (II) and B, above, as they note the number of judgments written by each member of the Gleeson Court either as part of a unanimous effort with his or her colleagues, or in concurrence with, or dissent from them. Table D (I) presents this information in respect of all cases, with D (II) dealing only with the constitutional subset.

TABLE D (I) – ACTIONS OF INDIVIDUAL JUSTICES: ALL CASES

|

|

Number of

Judgments

|

Participation

in Unanimous

Judgment

|

Concurrences

|

Dissents

|

|

Gleeson CJ

|

226

|

30 (13.2%)

|

181 (80.0%)

|

15 (6.6%)

|

|

Gaudron J

|

201

|

20 (9.9%)

|

158 (78.6%)

|

23 (11.4%)

|

|

McHugh J

|

203

|

25 (12.3%)

|

142 (69.9%)

|

36 (17.7%)

|

|

Gummow J

|

222

|

29 (13.0%)

|

184 (82.8%)

|

9 (4.0%)

|

|

Kirby J

|

226

|

19 (8.4%)

|

130 (57.5%)

|

77 (34.0%)

|

|

Hayne J

|

217

|

27 (12.4%)

|

177 (81.5%)

|

13 (5.9%)

|

|

Callinan J

|

222

|

22 (9.9%)

|

160 (72.0%)

|

40 (18.0%)

|

A number of comments may be made about these results. An obvious one is that the rarity of unanimous judgments is borne out by the figures in respect of all justices – they represent less than one sixth of the judgments signed off on by any member of the Court. Of course, this is far from surprising given the size of the High Court bench – Table B made it clear that unanimity is unlikely to flourish with the addition of more judges with whom to disagree. But if we move across this table we start to get an indication as to the level of consensus in the Court and the impediments to greater unanimity. The rates of concurrence can be seen as existing in three bands. Chief Justice Glee son, along with Gaudron, Gummow and Hayne JJ are all within 4 per cent of each other in respect of their fairly high propensity to agree with the final result of the Court. Justices McHugh and Callinan are slightly below this with 69.9 per cent and 72.0 per cent respectively. Lastly, Kirby J is a marked outsider with only 57.5 per cent of his judgments sharing in the Court’s response – and he was also least likely to participate in a unanimous opinion.

These three bands are borne out by a look at the dissent rate. Instantly we see that Justice Kirby’s level of dissent far outstrips (in fact is almost double) that of his nearest brethren, McHugh and Callinan JJ. With a dissent rate slightly in excess of a third of all his opinions, Kirby J seems secure in cementing a position as the High Court’s ‘Great Dissenter’.[51] I am somewhat cautious about using this title, most commonly associated with Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes of the United States Supreme Court.[52] As Shea has said, the remarkable thing about Holmes was not so much ‘the volume of his dissenting opinions, but the fact that many of them, over the course of time, were adopted as controlling authority by new majorities of Supreme Court Justices’.[53] If it is on this basis that the title is used, then only time will tell if it may fairly be applied to Kirby J with respect to his formidable dissent rate. But if the simple delivery of minority opinions suffices, Justice Kirby’s nearest rival would be Murphy J, previously perceived to be a somewhat exorbitant dissenter but who, with a rate of a mere 21.6 per cent,[54] now seems quite a mild case. Continuing to work backwards, McHugh and Callinan JJ hover around 18 per cent – portraying them as reasonable dissenters in their own right. It is still possible to group the remaining justices as a third band, but admittedly it is a slacker one than formulated with respect to concurrences, due to Justice Gaudron’s dissent rate being almost equidistant to that of McHugh J and that of Gleeson CJ. Justice Gummow’s very low dissent rate accords perfectly with his having the highest rate of concurrences.

Having looked through the table, the unanimity figures acquire a greater perspective. Despite any cohesiveness in outlook which we may tentatively presume amongst Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, Gummow and Hayne JJ,[55] as a group of four working alongside two judges with robust dissent rates and one whose dissension is quite frankly phenomenal, it is no mystery why the relatively high rates of concurrence do not translate into more unanimity. This is not simply to suggest that it is the dissents themselves which are destructive of opportunities for unanimous judgments - that much is obvious. Rather, my point is a wider one – the dissent rates indicate a general climate of pronounced individuality which may be observed in those even more frequent occasions where there is a high degree of concurrence across all sitting judges.[56] Of course, a court which has tended to follow the English tradition of seriatim opinion delivery is a natural environment in which to find this trait. But the relatively low rate of unanimity is especially worth commenting upon when one considers that upon his arrival as Chief Justice, Gleeson implemented conferencing procedures with a view, if not to building consensus, then at least to ensuring better communication and exchange of ideas amongst the judges.[57] But this hypothesis can be further, and perhaps better, explored when we move to consider the voting alignments and joint judgment authorship tables shortly.

Before turning to those, let us consider the actions of justices in the constitutional cases:

TABLE D (II) – ACTIONS OF INDIVIDUAL JUSTICES: CONSTITUTIONAL CASES

|

|

Number of

Judgments

|

Participation

in Unanimous

Judgment

|

Concurrences

|

Dissents

|

|

Gleeson CJ

|

59

|

5 (8.4%)

|

52 (88.1%)

|

2 (3.3%)

|

|

Gaudron J

|

59

|

4 (6.7%)

|

49 (83.0%)

|

6 (10.1%)

|

|

McHugh J

|

56

|

4 (7.1%)

|

41 (73.2%)

|

11 (19.6%)

|

|

Gummow J

|

61

|

5 (8.1%)

|

53 (86.8%)

|

1 (1.6%)

|

|

Kirby J

|

59

|

3 (5.0%)

|

39 (66.1%)

|

17 (28.8%)

|

|

Hayne J

|

57

|

4 (7.0%)

|

49 (85.9%)

|

4 (7.0%)

|

|

Callinan J

|

56

|

1 (1.7%)

|

40 (71.4%)

|

15 (26.7%)

|

There are several interesting features of this table, especially when compared with the behaviour of the justices generally as evinced by Table D (I), above. The likelihood of participation in a unanimous opinion is reduced for all, but the concurrence and dissent rates take some fairly unpredictable turns. All justices with the exception of Callinan J display an increased propensity to concur in the result of constitutional cases compared to their normal response. Admittedly, the Chief Justice aside, the increase is rather slight and Kirby J is still least likely of all other members of the Court to concur. Justice Callinan’s decrease in concurrence is so insubstantial as to remain steady for all intents and purposes.

What adds a dimension here is the change to the dissent rates. For one, Kirby J has not only reduced his rate of dissent to 28.8 per cent, but he now finds himself in very close company with Callinan J on 26.7 per cent – seemingly these two judges are just as likely to be in the minority in a constitutional case as each other, though of course, not necessarily in the same cases. Justice McHugh’s rate of dissent is also up but nowhere near as dramatically as that of Callinan J. The remaining four judges have not remained perfectly steady either – nor have they fared similarly in a breakdown of these cases. Justice Hayne’s dissent rate has increased mildly, whilst Justice Gaudron’s has dipped. Chief Justice Gleeson and Justice Gummow’s dissent rates – which are already low in general – are effectively halved in respect of constitutional cases.

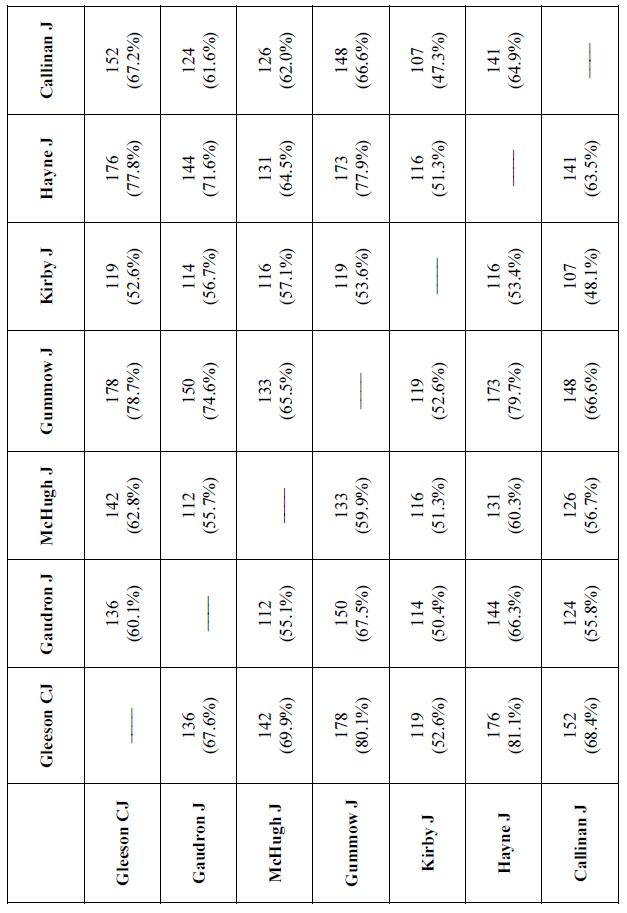

The purpose of Tables E (I) and (II) and F (I) and (II), below, is to indicate in two distinct ways the levels of agreement existing between the individual justices. Tables E (I) and (II) note the number of times each justice voted with others to dispose of a case in the same way. As alluded to in Part III, above, I have not adopted the stricture, employed by the Harvard Law Review and those investigating voting blocs, of only seeing agreement where there is total concurrence in the reasons for the vote – be it through co-authorship of the

judgment or a simple concurrence without more.[58] Instead, in addition to these blatant forms of agreement, I have included separate opinions which contain an individual statement of reasons but which still arrive at the same result as the Court. This is not to say that I reject entirely the ‘reasons are more important than the outcome’ approach,[59] but upon reflection I think it has greater relevance in the context of the United States Supreme Court where concurring judgments represent a breaking away from – and thus something of a direct challenge to – the reasons contained in the ‘opinion of the Court’. In courts that give seriatim judgments, it seems uncomfortably rigid to deny the existence of consensus simply because it lurks behind individual expression. Certainly, the numerous voices with which a majority may speak seem to cause little precedential angst for subsequent courts – in fact, it probably provides a welcome flexibility. Where this strict approach has been applied in respect of non-American decisions, it has been to detect voting ‘coalitions’[60] – a term I have consciously avoided using here. I appreciate that ‘coalition’ emphasises a higher degree of cohesion than arises when two judges independently reach the same outcome for very different reasons. Those studies seeking to identify steady alliances of justices who dominate the court’s jurisprudence are perfectly right to discount individual concurrences which bear an uncertain relationship to, and share only an indeterminate commonality with, the approach of the rest of the majority. But this only further illustrates the limitations of research into coalitions – given its reliance upon such a strict premise, it will not recognise agreement in a situation where all judges write separately, even when they may all reach the same result.[61]

Tables E (I) and (II) embrace all instances of agreement between justices as to the resolution of a matter – without requiring the individuality of the judge to be suppressed behind the single approach of a coalition. These tables set their sights somewhat lower and record simply voting alignments not blocs, though of course, the latter’s inclusion is implicit as one form of agreement. The presence of a like approach to resolution of the dispute is used as an indicator of substantive agreement between the particular justices, though obviously, the very real limitation upon Tables E (I) and (II) is that there may indeed be significant disagreement in the reasoning amongst the concurring judges. Whilst this deficiency may be avoided by the identification of clear coalitions only, that occurs, as I have just indicated, at the corresponding cost of ignoring the true width of consensus behind a collection of individual opinions. The precise extent of consensus lies somewhere between the results reached by the two methods – it is certainly more than will be revealed through a coalition study yet highly unlikely to be as much as indicated by simple concurrence in the result of the Court. The final thing to note about Tables E (I) and (II) is that all clear voting alignments are tallied regardless of success. So the agreement between a minority of judges as to the outcome of a case is tallied alongside that of the majority.

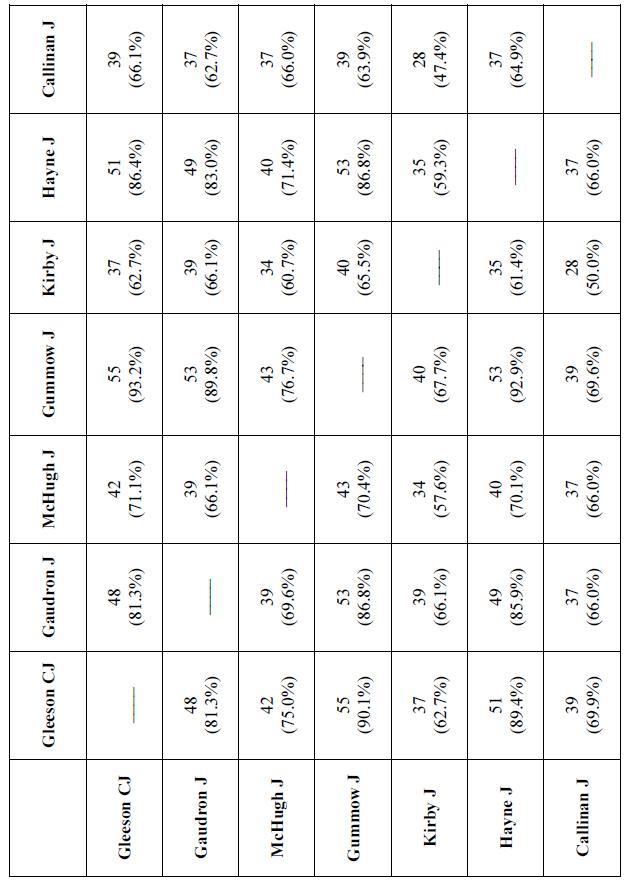

Tables F (I) and (II) redress the breadth of Tables E (I) and (II) by only recording participation in joint judgments – and, in accordance with the comments in Part III, above, this does not include mere statements of concurrence by other judges. The purpose of these tables, therefore, is to point to the most explicit form of agreement there is – where two or more justices share the one opinion so completely that it belongs to them in partnership.

In all four tables, the raw figures are the number of times a justice voted or co-authored with each of his or her colleagues. This is then followed by an indication of the frequency of each particular alignment or joint-judgment as a percentage out of all the cases which that individual justice determined. These tables should be read horizontally rather than vertically in order that the percentages be consistent.

TABLE E (I) –VOTING ALIGNMENTS: ALL CASES

TABLE E (II) – VOTING ALIGNMENTS: CONSTITUTIONAL CASES

The figures presented in Tables E (I) and (II), above, go some way to indicating the varying levels of influence of members of the Court. I stress that throughout the remainder of the paper I am merely stating that the statistics suggest the comparative sway which a judge may hold amongst his or her colleagues. To arrive at much firmer conclusions in this respect would require all sorts of studies of the Court and its output – some of which, such as substantive analysis of the transcripts and judgments, are already performed by High Court scholars,[62] while others, such as interviews with the justices themselves, scrutiny of notes from conferences, draft judgments and other papers, would seem much less likely.[63] The statistical information compiled here is not an end in itself – it hints at deeper currents.

In Table E (I) we see that all justices voted least with Kirby J than any of their other colleagues, with the exception of Gaudron and McHugh JJ (both those justices instead being marginally the least likely to vote with each other). A glance along Justice Kirby’s row shows that he only sided with any of his fellow judges on approximately half of the possible occasions he had to do so. At the other end of the spectrum, all members of the Court, barring Gaudron J, voted in accord with Gleeson CJ more often than anyone else. However, it is worth noting that Gummow J is not far behind, with Glee son CJ and Gaudron J voting most similarly to him, and Kirby J being just as prepared to favour a resolution in conjunction with Gummow J as he is with the Chief Justice. Justice Hayne is also noticeably dominant in attracting support from across the Court for his resolution of matters. Of course, these results are not so surprising when one recalls the high level of concurrence and very low rates of dissent of Gleeson CJ and Gummow and Hayne JJ, demonstrated by Table D (I), above.

Turning to Table E (II), the picture in respect of constitutional cases is interestingly altered. Instantly, we can see that proportionally the frequency of alignment has increased across the board, indicating perhaps that the justices are less creative in fashioning individual solutions to constitutional problems. Some of the shifts as against what has just been observed in respect of the total caseload are striking. The most obvious is the clear centrality of Gummow J as a barometer to the entire Court in constitutional cases.[64] All six of his colleagues voted with him more often than any other justice (though Callinan J was just as likely to agree with Gleeson CJ). Both the Chief Justice and Hayne J voted with Gummow J in around 93 per cent of the constitutional cases on which they sat. The ascendancy of Gummow J in constitutional matters may convey the appearance that the Chief Justice has less influence in this area than he does overall, but he has not been dramatically usurped. He remained a very likely voting partner for all justices. The same is true of Hayne J – and additionally in this context, Gaudron J also. With the exception of Hayne J, all members of the Court were noticeably more likely to find themselves aligned with Gaudron J over other justices in constitutional cases than they were generally. The remaining three justices still have the lowest alignment scores. But while, in this subset of cases, Kirby J had a marginal increase in instances of agreement with Gaudron and Gummow JJ relative to the other alignments of those judges, Justice Callinan’s position as a preferred voting partner relative to his other colleagues appeared to slip with respect to all members.

Turning now to Tables F (I) and (II), below, we can place these early perceptions about agreement amongst the justices to a more rigorous test based upon the frequency with which they join in authorship of an opinion. Does that particularly explicit indicia of consensus bear out the level of agreement indicated by the patterns of similar voting we have just encountered?

TABLE F (I) – JOINT JUDGMENT AUTHORSHIP: ALL CASES

TABLE F (II) – JOINT JUDGMENT AUTHORSHIP: CONSTITUTIONAL CASES

If anything, these tables present a clearer picture of the position in which the justices often find themselves vis-à-vis each other. In respect of the entirety of cases across the period as recorded in Table F (I), Gleeson CJ and Gummow and Hayne JJ have a marked tendency towards co-authorship with each other. In particular, the two justices were parties to joint judgments with each other in over half the cases in which they presided. Additionally, all three were the favoured writing partners of the other members of the Court. Barring Gaudron J being Justice Callinan’s third most frequent co-author over Hayne J, Gaudron, McHugh, Kirby and Callinan JJ all joined the Chief Justice and Gummow and Hayne JJ in co-authorship more often than they teamed with each other. Aside from this trio, the most collaborative justice tended to be Gaudron J, followed by McHugh J. And in a table with quite clearly discernible trends, none was more apparent than that Kirby and Callinan JJ are the determined individualists of the Court. The former teamed the least often with any of his colleagues – and by a sizeable margin. Justice Callinan had a higher rate of co-authorship but was a definite runner-up to Justice Kirby – his Honour was the next least likely partner in a judgment for all those on the bench.

Much of this is simply translated to the specific setting of constitutional law cases found in Table F (II), but there are a few observations worth making. While the trio of Gleeson CJ and Gummow and Hayne JJ certainly retains its centrality, Gaudron J appears to acquire a greater share of this. Admittedly, this is not to the extent of her Honour having co-authored opinions the most often with any other justice, but she ties in first place (with Gleeson CJ and Hayne J) for co-authorship with Kirby J, and is the next most collaborative with Gummow, Hayne and Callinan JJ (in respect of joining with the latter, she is tied with the Chief Justice and McHugh J). Between this table and the last, there is almost no change to the tail end at all – a very clear growth in individual expression as one moves from McHugh J, to Callinan J and ultimately to Kirby J. The results in respect of Kirby J are strikingly low and might be seen to reflect his Honour’s methodological isolation from the rest of the Court in constitutional cases. Statements of constitutional principle such as that offered by Kirby J in Newcrest Mining (WA) Ltd v Commonwealth[65] and his marked intolerance for originalist approaches,[66] has set his Honour on a course where the opportunity for joint-judgment must be severely constrained while his brethren remain unpersuaded by his approach. The same might be expected to a lesser extent in respect of McHugh J who has also been fairly explicit about adhering to a particular methodology,[67] though the results in respect of his Honour are not so very pronounced that we can readily make such an inference. This is probably also largely due to the greater acceptance which Justice McHugh’s approach would appear to have found amongst his colleagues.

Table F (III), below, aims to give some dimension to the figures just provided in F (II) by listing the joint judgment authors, and indicating by case reference the occasions on which they partnered. This is not, as I have already made clear, a study into voting blocs which successfully determine the outcome of a case. Table F (III) is intended merely as a record of the various occurrences of co-authorship:

TABLE F (III) – JOINT JUDGMENT AUTHORSHIP: CONSTITUTIONAL CASES[68]

|

No of

Js

|

Justices

|

Case Reference

|

|

7

|

Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, McHugh, Gummow,

Kirby, Hayne and Callinan JJ

|

(161/489)

|

|

6

|

Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, McHugh, Gummow,

Kirby and Hayne JJ

|

(169/607)

|

|

Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, McHugh, Gummow,

Hayne and Callinan JJ

|

(159/109); (163/576);

(170/111); (171/155);

(172/366); (18 1/371);

(191/543)

|

|

|

5

|

Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, McHugh, Gummow and

Hayne JJ

|

(167/105); (170/659);

(172/625)

|

|

Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, Gummow, Kirby and

Hayne JJ

|

(156/563)

|

|

|

Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, Gummow, Hayne and

Callinan JJ

|

(192/217)

|

|

|

Gaudron, McHugh, Gummow, Kirby and

Hayne JJ

|

||

|

4

|

Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, McHugh, and Gummow JJ

|

(187/409)

|

|

Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, McHugh, and Hayne JJ

|

(188/241)

|

|

|

Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, Gummow and Hayne JJ

|

(184/113); (191/1)

|

|

|

Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, Gummow and Callinan JJ

|

(168/86)

|

|

|

Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, Kirby and Hayne JJ

|

(166/259)

|

|

|

Gleeson CJ, McHugh, Gummow and Hayne JJ

|

(176/644)

|

|

|

Gaudron, McHugh, Gummow and Hayne JJ

|

(177/436)

|

|

|

Gaudron, McHugh, Gummow and Callinan JJ

|

(164/520)

|

|

|

3

|

Gleeson CJ, Gaudron and Gummow JJ

|

(177/329)

|

|

Gleeson CJ, McHugh, and Gummow JJ

|

(163/501); (183/645)

|

|

|

Gleeson CJ, McHugh, and Callinan JJ

|

(165/171)

|

|

|

Gleeson CJ, Gummow and Hayne JJ

|

(163/648); (173/619);

(175/339); (185/111)

|

|

|

Gaudron, McHugh and Gummow JJ

|

||

|

Gaudron, Gummow and Callinan JJ

|

(166/159)

|

|

|

Gaudron, Gummow and Hayne JJ

|

(158/527); (168/8);

(180/301); (185/233);

(189/161); [2003] HCA 3‡

|

|

|

2

|

Gleeson CJ and Gaudron J

|

(160/638)

|

|

Gleeson CJ and Gummow J

|

(161/318); (166/545);

(188/1)

|

|

|

Gleeson CJ and Kirby J

|

(167/392)

|

|

|

Gaudron and Gummow JJ

|

(176/219); (176/449)

|

|

|

Gaudron and Hayne JJ

|

(187/529)

|

|

|

McHugh and Callinan JJ

|

(161/318)

|

|

|

Gummow and Hayne JJ

|

(162/1); (163/270);

(165/171); (172/257);

(182/657); (185/1)

|

|

|

Hayne and Callinan JJ

|

(177/329)

|

* At the time of writing, the case of Plaintif S157/2002 v Commonwealth [2003] HCA 2 is yet to be reported in the Australian Law Reports.

† At the time of writing, the case of Roberts v Bass [2002] HCA 57 is yet to be reported in the Australian Law Reports.

‡ At the time of writing, the case of Austin v Commonwealth [2003] HCA 3 is yet to be reported in the Australian Law Reports.

With the recent change in the composition of the Gleeson Court occurring close to the end of its first five years, the time was ripe for a basic empirical approach to be taken to its work in order to try to discern patterns of behaviour – both institutionally and from the Justices as individuals. Of course, political scientists and those legal academics taken with the jurimetrics movement would be in a position to subject this material to a range of sophisticated empirical techniques with a view to teasing out conclusions of a more specific nature. The methods adopted here have been comparatively straightforward and devised simply to capture a sense of the Court through examining not (as is more commonly the case) how it explains itself, but rather how it acts.

We may consider the statistics compiled and find our existing impressions confirmed. Additionally, we may be mildly surprised by the frequency of various happenings where we had not previously perceived any trend. Doubtless, different observers may be able to draw different conclusions from the material I have presented here – and, of course, one must apply a caveat given the necessary limitations to the sample size. As such, I desist from the temptation to read too much into the figures. However, two things evidently stand out in respect of what the statistics indicate about the Gleeson Court on constitutional law. The first is that the Court seems to have had a solid core led by Gummow J and comprising, in rough order of influence, Glee son CJ and Hayne and Gaudron JJ. Of course, to repeat my earlier qualification, that is the simple picture suggested by the figures themselves. Further substantive analysis would undoubtedly lead to better illumination of the degree to which the justices are swayed by each other’s views. But certainly, those four justices have most consistently commanded the majority position of the Bench across the five year period. The replacement of Gaudron J with Heydon J would not seem likely to result in a dramatic weakening of the hold which that portion of the Court has in constitutional matters. Whilst one should always be wary of making predictions, it seems fair to suggest that Heydon J has given indications that he is likely to find more common ground with the approach of the dominant trio than he is with those less obviously in the centre of the court – McHugh, Kirby and Callinan JJ.[69]

The second observation is that although Callinan J appears almost as likely to dissent in constitutional matters, the indication from the tables of voting alignments and joint judgment authorship is that Kirby J is really running his own race. This tends to obscure the position of Callinan and McHugh JJ both of whom are removed from the centre of the Court to a not insignificant degree in their own right. It also invites speculation about the competing fealties of individualism and institutionalism. Justice Kirby’s position on the Court is one which clearly displays an overriding commitment to the former over the latter. There is a wide body of literature which attempts to weigh the benefits and harm which pronounced disagreement may have upon an institution.[70] It is obviously outside of the scope of this paper to explore those arguments now, but clearly the prevalence of dissent in the present Court ensures that is a debate to which we must stay attuned.

(Throughout these notes italics indicate constitutional cases)

The purpose of the notes contained in this appendix is to identify when and how discretion has been exercised by the researcher in compiling the statistical tables discussed throughout this paper. As the Harvard Law Review editors stated, when explaining their own methodology, ‘the nature of the errors likely to be committed in constructing the tables should be indicated so that the reader might assess for himself the accuracy and value of the information conveyed’.[71]

CASE REPORTS INVOLVING A NUMBER OF MATTERS – HOW TALLIED

|

Reports containing a number of matters but tallied singly due to a common

substratum of facts which leads to little or no distinction

being drawn between

the matters in the judgments:[72]

|

|

(161/399); (161/489); (162/577); (1 63/501); (1 64/520);

(167/392); (167/575); (168/8); (169/385); (169/677); (171/613);

(172/257); (173/665); (175/338); (176/545);

(177/329);[73] (179/416); (179/625); (183/404);

(184/113); (191/1); (192/129); (193/1)

|

|

Reports tallied multiple times due to distinctions being drawn between the

matters in the judgments and orders made:[74]

|

|

Tallied as two

|

Tallied as four

|

|

(180/402); (190/601); (191/449); (193/3 7); [2003] HCA 4.

|

(1 63/270)[78]

|

DECISIONS TO TALLY DISSENTS WARRANTING EXPLANATION

(175/338) Gaudron J would grant special leave but dismiss the appeal. The majority order is to dismiss the application for leave. Her Honour’s reason for the different order (which, admittedly, gives the applicant the same practical result) is based upon her opinion as to the operation of provisions of the Customs Act rather than the central constitutional issue. However, this point of difference from the majority leads to her variation of the resolution of the matter and tallying as a total dissent.

(176/219) Callinan J dissents as well as McHugh J despite the headnote accompanying the report. His Honour does not completely agree with the final orders as he would not grant certiorari. As only a partial concurrence in the final orders, this is tallied as a dissent.

(185/335) Callinan J differs from the Court’s orders by requiring interest to be paid. The majority leaves that issue to the Federal Court to determine. As only a partial concurrence in the final orders, this is tallied as a dissent.

(189/161) Callinan J only allows the demurrers in part and is therefore tallied as dissenting.

(190/313) McHugh and Callinan JJ are tallied as concurring rather than dissenting. The form in which they answer the questions asked of the Court is slightly different from the majority (it is expressed with less caution) – but essentially the same responses are given.

(190/601) The two matters contained in this report require the justices to answer a number of discrete questions in respect of each. For Matter S36 there is a clear 4:3 majority in favour of one set of answers. This is not the case in Matter S89, the result of which is arrived at by composite of the various diverse opinions (no fewer than five). Only Justice Gaudron’s judgment completely reflects the final orders of the Court in this matter. Consequently, and in accordance with the methodological constraints requiring absolute concurrence in order to avoid dissent, there are six dissenting opinions in respect of Matter S89.[79] It should be noted that, as recorded above, these matters were tallied separately.

(192/181) Kirby J agrees with the majority that the conviction should be quashed but he does not order a new trial. As only a partial concurrence in the final orders, this is tallied as a dissent.

(192/217) Kirby J agrees with the majority that the appeal should be dismissed but he does not concur on the matter of costs. As only a partial concurrence in the final orders, this is tallied as a dissent.

[*] Senior Lecturer, University of Technology, Sydney. A much abbreviated version of this paper was presented at the 2003 Gilbert + Tobin Centre of Public Law Constitutional Law Conference, Sydney, 21 February 2003. The author wishes to thank Professor George Williams, Lawrence McNamara and the three anonymous referees for their comments upon earlier drafts of this paper. I alone am responsible for any flaws.

[1] Stephen Gageler, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2001 Term’ [2002] UNSWLawJl 8; (2002) 25 UNSW Law Journal 194.

[2] The first such piece is Paul A Freund, ‘The Supreme Court, 1951 Term: Foreword: The Year of the Steel Case’ (1952) 66 Harvard Law Review 89.

[3] ‘The Supreme Court, 1948 Term’ (1949) 63 Harvard Law Review 119.

[4] Gageler’s success in doing so has been repeated by Justice Susan Kenny: Susan Kenny, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2002 Term’ (Paper presented at the Gilbert + Tobin Centre of Public Law Constitutional Law Conference, Sydney, 21 February 2003).

[5] There have, of course, been notable exceptions to this: see Tony Blackshield, ‘Quantitative Analysis: The High Court of Australia, 1964–1969’ (1972) 3 Lawasia 1; Tony Blackshield, ‘X/Y/Z/N Scales: The High Court of Australia, 1972–1976’ in Roman Tomasic (ed), Understanding Lawyers – Perspectives on the Legal Profession in Australia (1978) 133. In recent years there has been more activity on this front, chiefly by Russell Smyth: see Russell Smyth, ‘Academic Writing and the Courts: A Quantitative Study of the Influence of Legal and Non-Legal Periodicals in the High Court’ [1998] UTasLawRw 12; (1998) 17 University of Tasmania Law Review 164; Russell Smyth, ‘“Some are More Equal than Others” – An Empirical Investigation into the Voting Behaviour of the Mason Court’ (1999) 6 Canberra Law Review 193; Russell Smyth, ‘Other than “Accepted Sources of Law”? A Quantitative Study of Secondary Source Citations in the High Court’ [1999] UNSWLawJl 40; (1999) 22 University of New South Wales Law Journal 19; Russell Smyth, ‘What do Judges Cite? An Empirical Study of the “Authority of Authority” in the Supreme Court of Victoria’ [1999] MonashULawRw 2; (1999) 25 Monash University Law Review 29; Russell Smyth, ‘What do Intermediate Appellate Courts Cite? A Quantitative Study of the Citation Practice of Australian State Supreme Courts’ [1999] AdelLawRw 3; (1999) 21 Adelaide Law Review 51; Russell Smyth, ‘Law or Economics? An Empirical Investigation into the Influence of Economics on Australian Courts’ (2000) 28 Australian Business Law Review 5; Russell Smyth, ‘Who Gets Cited? An Empirical Study of Judicial Prestige in the High Court’ [2000] UQLawJl 2; (2000) 21University of Queensland Law Journal 7; Russell Smyth, ‘The Authority of Secondary Authority: A Quantitative Study of Secondary Source Citations in the Federal Court’ (2001) 9 Grifith Law Review 25; Russell Smyth, ‘Judicial Prestige: A Citation Analysis of Federal Court Judges’ [2001] DeakinLawRw 7; (2001) 6 Deakin Law Review 120; Russell Smyth, ‘Citation of Judicial and Academic Authority in the Supreme Court of Western Australia’ [2001] UWALawRw 1; (2001) 30 University of Western Australia Law Review 1; Russell Smyth, ‘Judicial Interaction on the Latham Court: A Quantitative Study of Voting Patterns on the High Court 1935–1950’ (2001) 47 Australian Journal of Politics and History 330; Russell Smyth, ‘Explaining Voting Patterns on the Latham High Court 193 5– 50’ [2002] MelbULawRw 5; (2002) 26 Melbourne University Law Review 88; and Russell Smyth, ‘Acclimation Effects for High Court Justices 1903–1975’ (2002) 6 University of Western Sydney Law Review 167. See also Richard Haigh, ‘“It is Trite and Ancient Law”: The High Court and the Use of the Obvious’ [2000] FedLawRw 4; (2000) 28 Federal Law Review 87; Patrick Keyzer, ‘The Americanness of the Australian Constitution: The Influence of American Constitutional Jurisprudence on Australian Constitutional Jurisprudence: 1988 to 1994’ (2000) 19 Australasian Journal of American Studies 25; and Paul E von Nessen, ‘The Use of American Precedents by the High Court of Australia, 1901–1987’ [1992] AdelLawRw 8; (1992) 14 Adelaide Law Review 181.

[6] Above n 3.

[7] Felix Frankfurter and James M Landis, ‘The Business of the Supreme Court at October Term, 1928’ (1929) 43 Harvard Law Review 33; Felix Frankfurter and James M Landis, ‘The Business of the Supreme Court at October Term, 1929’ (1930) 44 Harvard Law Review 1; Felix Frankfurter and James M Landis, ‘The Business of the Supreme Court at October Term, 1930’ (1931) 45 Harvard Law Review 271; Felix Frankfurter and James M Landis, ‘The Business of the Supreme Court at October Term, 1931’ (1932) 46 Harvard Law Review 226; Felix Frankfurter and Henry M Hart Jr, ‘The Business of the Supreme Court at October Term, 1932’ (1933) 47 Harvard Law Review 245; Felix Frankfurter and Henry M Hart Jr, ‘The Business of the Supreme Court at October Term, 1933’ (1934) 48 Harvard Law Review 238; Felix Frankfurter and Henry M Hart Jr, ‘The Business of the Supreme Court at October Term, 1934’ (1935) 49 Harvard Law Review 68; and Felix Frankfurter and Adrian S Fisher, ‘The Business of the Supreme Court at October Terms, 1935 and 1936’ (1938) 51 Harvard Law Review 577.

[8] Frankfurter was appointed to the United States Supreme Court on 30 January 1939. The series was concluded by his earlier co-author: Henry M Hart Jr, ‘The Business of the Supreme Court at October Terms, 1937 and 1938’ (1940) 53 Harvard Law Review 579.

[9] This was acknowledged by the editors in ‘The Supreme Court, 1967 Term’ (1968) 82 Harvard Law Review 63, 301.

[10] ‘The Supreme Court, 1960 Term’ (1961) 75 Harvard Law Review 40, 84–92.

[11] Above n 9.

[12] See Andrew Lynch, ‘Dissent: Towards a Methodology for Measuring Judicial Disagreement in the High Court of Australia’ (2002) 24 Sydney Law Review 470.

[13] Above n 3.

[14] As Blackshield has said, ‘like any intellectual method, quantitative analysis involves great simplifications, as one seeks to reduce a disorderly mass of empirical data to conceptual manageability’: Blackshield, ‘X/Y/Z/N Scales: The High Court of Australia, 1972–1976’, above n 5, 134.

[15] This is something of a balancing act. Again, Blackshield admitted: ‘we need a set of categories simple enough to be usable, but complex enough to illuminate the intricacies and inconsistencies of the human mind’: Blackshield, ‘X/Y/Z/N Scales: The High Court of Australia, 1972–1976’, above n 5, 134. Admittedly, this was in the context of his much more sophisticated ‘scalogram’ project but the essential tension which he highlights would seem universal in any research aiming to quantify an aspect of human existence.

[16] This is the central theme and substance of my paper above n 12.

[17] It is a similar story in respect of the Harvard Law Review which admitted that the construction of similar tables ‘is accomplished primarily through tabulations as mechanical and simple as counting’: above n 9, 302.

[18] See, eg, above n 5.

[19] At the time of writing, the Australian Law Reports were so up to date as to be almost complete. The date of the last judgment delivered by the High Court and reported in that series is 5 December 2002 (R v Carroll [2002] HCA 55; (2002) 194 ALR 1). By comparison, the Commonwealth Law Reports had only just reported the judgments in Yarmirr v Northern Territory (2001) 208 CLR 1 which was delivered on 11 October 2001. This case was reported in (2001) 184 ALR 113. The reason AustLI was not simply used for the entire study is that the organisation of material on that site would have posed difficulties in ensuring all cases for the relevant period were included. With the exception of recent cases, case law is not organised chronologically by AustLI. Thus, the possibility of overlooking relevant cases in the alphabetical lists or through use of the search engines mitigated against use of that resource for the bulk of the study.

[20] The justices in the natural court under study and their dates of appointment are Gleeson CJ (22 May 1998), Gaudron J (6 February 1987), McHugh J (14 February 1989), Gummow J (21 April 1995), Kirby J (6 February 1996), Hayne J (22 September 1997), and Callinan J (3 February 1998).

[21] Russell Smyth, ‘Judicial Interaction on the Latham Court’, above n 5, 334. For a detailed example of selecting a ‘natural court’ to study, see Tony Blackshield, ‘Quantitative Analysis: The High Court of Australia, 1964–1969’, above n 5, 11.

[22] Youngsik Lim, ‘An Empirical Analysis of Supreme Court Justices’ Decision Making’ (2000) 29 Journal of Legal Studies 721, 724; and Blackshield, ‘X/Y/Z/N Scales: The High Court of Australia, 1972–1976’, above n 5, 139.

[24] In doing so, I am both acting to my own preference and aiming to be consistent with the approach taken by Gageler, above n 1, 195. For an example of the reverse approach, see Peter J McCormick, ‘The Most Dangerous Justice: Measuring Judicial Power on the Lamer Court 1991–97’ (1999) 22 Dalhousie Law Journal 93, 97.

[25] See <http://www.austlii.edu.au> at 10 June 2003 .The ten cases are Graham Barclay Oysters Pty Ltd v Ryan [2002] HCA 54; Dow Jones & Co Inc v Gutnick [2002] HCA 56; Roberts v Bass [2002] HCA 57; Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v Victoria [2002] HCA 58; Aktiebolaget Hassle v Alphapharm Pty Ltd [2002] HCA 59; Re Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Afairs; Ex parte Applicants S134/2002 [2003] HCA 1; Plaintif S157/2002 v Commonwealth of Australia [2003] HCA 2; Austin v Commonwealth of Australia [2003] HCA 3; New South Wales v Lepore; Samin v Queensland; Rich v Queensland [2003] HCA 4; Boral Besser Masonry Limited (now Boral Masonry Ltd) v ACCC [2003] HCA 5.

[26] [2000] HCA 51; (2000) 175 ALR 1.

[27] Chiefly those involving a yearly breakdown such as Table A (II), below.

[28] Gageler, above n 1, 195.

[29] These cases were Egan v Willis [1998] HCA 71; (1998) 158 ALR 527; Durham Holdings Pty Ltd v New South Wales (2001) 177 ALR 436; and Mobil Oil Australia Pty Ltd v Victoria [2002] HCA 27; (2002) 189 ALR 161 (which also involved a question of Commonwealth judicial power).

[30] See, eg, DJL v Central Authority [2000] HCA 17; (2000) 170 ALR 659.

[31] See, eg, the catchwords prefacing Austral Pacific Group Ltd (in liq) v Airservices Australia [2000] HCA 39; (2000) 173 ALR 619. These concern s 51(i) and s 51(xxxi) but do not indicate the Court’s concern in that decision with distinguishing a fee for services from a tax. I am grateful to one of the anonymous referees for this example.

[32] Above n 9, 302.

[33] Lynch, above n 12.

[34] See Smyth, ‘Judicial Interaction on the Latham Court’, above n 5, 333; Smyth, ‘Explaining Voting Patterns on the Latham High Court 1935–50’, above n 5, 101; Smyth, ‘Acclimation Effects for High Court Justices 1903–1 975’, above n 5, 175.

[35] A simple ‘I agree’ judgment ‘is no different in substance from being a party to a joint judgment, although care must be taken to leave no doubt about what it is with which the Justice agrees’: Michael Coper, ‘Concurring Judgments’ in Tony Blackshield, Michael Coper and George Williams (eds), The Oxford Companion to the High Court of Australia (2001) 129–3 0.

[36] It must be admitted that this is hardly a problem of much practical significance to the cases involved in this study. My central concern with allowing a fluidity between these two situations is that it risks obscuring the significance of when the justices choose to speak together by writing jointly, as opposed to the many instances where they simply defer to the solution proposed by one of their number. Even apart from any symbolic importance or enhanced precedential value which may attach to a unanimous opinion, clearly a different process has taken place in the Court’s determination of the matter than when an individual author is agreed with. It seems undesirable to lose that nuance unless necessary for a particular purpose. Additionally, the level of agreement between the justices can be reflected in other ways (such as the tallying of voting alignments in Tables E (I) and (II) of this paper, below) which do not threaten this distinction.

[37] Additionally, this rule will not apply in cases where the final orders are determined by application of a procedural rule (for example, resolution of deadlock between an even number of justices through use of the Chief Justice’s casting vote). This type of case should be discounted from any study attempting to quantify dissent. No case of this sort arose in the period under examination here.

[38] See, eg, (1988) 102 Harvard Law Review 143, 350.

[39] There have been complaints in recent times that the Court’s ‘opinions sometimes exhibit a Byzantine complexity that borders on self-caricature, to such an extent that it becomes a “Herculean task” to try to determine “whether an actual majority exists behind any proposition”’: McCormick, above n 24, 98. It is not a problem of which the Supreme Court justices are unaware: Ruth Bader Ginsburg, ‘Remarks on Writing Separately’ (1990) 65 Washington Law Review 133, 148–50.

[40] See John Alder, ‘Dissents in Courts of Last Resort: Tragic Choices?’ (2000) 20 Oxford Journal of Legal Studies 221, 240; Coper, above n 35; Ijaz Hussain, Dissenting and Separate Opinions at the World Court (1984) 8; Michael Kirby, ‘Law at Century’s End’ [2001] MqLawJl 1; (2000) 1 Macquarie Law Journal 1, 13; Donald E Lively, Foreshadows of the Law: Supreme Court Dissents and Constitutional Development (1992) xx; Andrew Lynch, ‘Dissenting Judgments’ in Tony Blackshield, Michael Coper and George Williams (eds), The Oxford Companion to the High Court of Australia (2001), 216–8; Lynch, above n 12, 476–7; McCormick, above n 24, 102–3.

[41] Above n 38.

[42] Lynch, above n 12, 481–3, 487–91, 498–500.

[44] Mark A Kadzielski and Robert C Kunda, ‘The Unmaking of Judicial Consensus in the 1930s: An Historical Analysis’ (1983) 15 University of West Los Angeles Law Review 43, 47.