University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

HIGH COURT CONSTITUTIONAL CHALLENGES TO CRIMINAL LAW AND PROCEDURE LEGISLATION IN AUSTRALIA

LUKE MCNAMARA[*] AND JULIA QUILTER[**]

Scholars of criminal law and criminalisation have paid insufficient attention to the use of constitutional challenges in the courts as a strategy for influencing the nature and scope of criminal laws in Australia. This article makes a contribution to filling this gap by analysing 59 High Court of Australia decisions handed down between 1996 and 2016. Our analysis highlights the sorts of criminal laws that have been the subject of constitutional scrutiny, the types of constitutional arguments that have been advanced, and the outcomes achieved. We show that outright ‘wins’ are rare and that, even then, the concept of ‘success’ is complex. We highlight the need to consider the wider and longer-term effects of constitutional adjudication, including how legislatures respond to court decisions. We conclude that challenges to constitutional validity in the High Court represent a limited strategy for constraining how governments choose to legislate on criminal responsibility, procedure and punishment.

The research on which this article reports is motivated by three coinciding phenomena associated with 21st century criminal lawmaking in Australia. First, there has been a noticeable growth in, and diversification of, the modalities of ‘criminalisation’[1] employed by legislators in response to identified harms and risks[2] (and uncertainties).[3] A number of these developments involve extensions of the punitive and other coercive authority of the state beyond the traditional parameters of criminal responsibility, and in ways that challenge traditional liberal democratic accounts of when the state is entitled to impose deprivations on a person’s liberty. Examples include: the creation of ‘control order’ regimes directed primarily at terrorism and bikie gangs;[4] the introduction of post-sentence preventive detention regimes for ‘high-risk’ offenders;[5] and the expansion of police powers in relation to the management of protest activities.[6]

Second, in Australia and elsewhere, scholars in criminal law and criminology have responded to disquiet about these and other forms of perceived ‘over-criminalisation’.[7] By ‘over-criminalisation’ we mean the normative judgment that a law is unnecessarily or unfairly punitive, pushing the criminal law – whether its substantive offences, or procedures, or both – and, therefore, the coercive powers of the state, beyond legitimate limits. Scholars have produced a significant body of literature which critiques such developments in resorting to criminal law ‘solutions’, and which attempts to theorise the legitimate normative limits of criminalisation as a public policy mechanism.[8]

Third, in Australia, individuals and organisations concerned about instances of perceived over-criminalisation, and their lawyers, have pursued constitutional challenges in the High Court as a prominent strategic mechanism for attempting to stop or restrict perceived over-criminalisation. To some extent, the rise in popularity of this strategy may be seen as an attempt to enliven the ‘constitutional court’ role of the High Court akin to the role played by constitutional courts in other countries – such as the Supreme Court of Canada, courtesy of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms,[9] or the United States Supreme Court, by virtue of the United States Bill of Rights.[10] Of course, compared to those two constitutional courts, the ‘hooks’ on which invalidity arguments can be hung in the High Court are very few.

The aim of this article is to make a contribution towards understanding High Court constitutional challenges as a method of influencing the parameters of criminal lawmaking in Australia. In what circumstances has this strategy been successful? What have been its effects on lawmaking practices, both in the immediate aftermath of specific decisions and over time?

The context in which we approach these questions is a wider project which examines the drivers of resorting to new forms of criminalisation as a public policy tool, and which evaluates strategies for attempting to influence the parameters of criminalisation.[11] We recognise that constitutional law scholars have previously examined a number of the cases that form part of the present study, most notably in relation to the most widely used constitutional invalidity argument in the criminal law context: the ‘institutional integrity’ principle based on Chapter III of the Australian Constitution, with its origins in the High Court’s 1996 decision in Kable v Director of Public Prosecutions (NSW).[12] Our aim in writing this article is not to duplicate or challenge the insights yielded by this important body of work.[13] Rather, this article is motivated by our own recognition that scholars of criminal law and criminalisation have tended to ignore this important dimension of the story of contemporary criminal lawmaking in Australia. It represents the first attempt by criminal law and criminalisation scholars to approach High Court constitutional challenges as one of the techniques for attempting to interrupt and influence governments’ uses of criminal law mechanisms that warrants scholarly attention and scrutiny.

Our analysis addresses not only ‘Kable challenges’, but also challenges to criminal law statutes brought on other constitutional grounds, including the implied freedom of political communication, the guarantee of trial by jury for Commonwealth indictable offences in section 80 of the Constitution, and the supremacy of Commonwealth laws in cases of inconsistency between state and Commonwealth laws, by virtue of section 109 of the Constitution. Nonetheless, we recognise the significance of the High Court’s decision in Kable and therefore adopt the year it was handed down (1996) as the starting point for the review period in the present study. Kable was critical to ‘[t]he move to centre stage of Ch III of the Constitution’,[14] which has been described as ‘one of the defining features of ... Australian constitutional law’ during the 1990s.[15] Kable is widely and rightly seen as a pivotal event in the emergence of the public interest strategy of pursuing constitutional validity to statutes which are alleged to effect over-criminalisation in one way or another.

Part II of this article explains the project’s research design, including research questions and methodology. Part III presents a brief quantitative snapshot of the dataset. Part IV discusses the project’s major findings regarding the use of High Court constitutional challenges as a strategy for influencing the parameters of criminal law and procedure legislation in Australia.

The project’s aim is to illuminate several features of the use of High Court constitutional challenges to criminal law statutes. What sorts of criminal law and procedure statutes have been the subject of constitutional challenge? What sorts of constitutional grounds have been relied on? How often, and in what sorts of instances, have constitutional challenges resulted in a High Court finding of invalidity? Are there other immediate outcomes falling short of a ruling of invalidity that have nonetheless limited the government’s preferred criminalisation parameters? Are any patterns discernible when it comes to ‘success’ rates – whether in terms of the type of statute, type of constitutional ground or other variable? Post-decision, how have governments responded to specific High Court decisions in constitutional challenge cases, including where the decision impeded the government’s policy objectives as reflected in the legislation in question, and where the decision did not? Is there any evidence that High Court constitutional adjudication (both individual cases and cumulatively) has exerted influence on the subsequent approach of governments in deploying criminalisation legislation?

It is important to note that it is not our intention in this article to pass judgment on the decisions of litigants, and their legal representatives, who have pursued constitutional challenges to legislation that affects them. We are not privy to the myriad personal, strategic and other factors that were considered in deciding to take a matter to the High Court. Relatedly, and as is apparent from our explanation of methodology in the next section of the article, we neither necessarily endorse the various assertions advanced in the cases we reviewed about the claimed invalidity of the legislation in question, nor have we attempted to evaluate the ‘correctness’ of the High Court’s decision in the cases reviewed for this study. Rather, our aim is to identify the distinctive features of constitutional litigation as a strategy for challenging the legitimate parameters of statutory criminal lawmaking in Australia.

We collected all High Court decisions for the 20-year period from 1996 to 2016 which involved a constitutional validity challenge to a criminal law statute enacted by an Australian legislature.[16]

We defined ‘criminal law statute’ broadly[17] to include any statute that operates in relation to the criminal justice system, including statutes that: create a new offence or expand an existing offence; increase a penalty, establish a mandatory penalty or change sentencing laws; affect the rights and conditions of prisoners; increase the intrusive powers of police or other state agencies (including control orders, compulsory questioning/examination); provide for post-sentence detention or restrictions; or otherwise change the procedures by which criminal offences and allied powers are administered.

Our chief concern is with High Court challenges that are pursued with the primary and explicit public interest objective of achieving the ‘repeal’ of legislation which is regarded by the initiating litigant as amounting to ‘over-criminalisation’. Such challenges are typically launched shortly after the enactment of the legislation in question. However, we note that our project parameters also include constitutional challenges which are not necessarily motivated by wider public interest considerations or an over-criminalisation characterisation. Rather, the challenge to constitutional invalidity is designed to advance the interests of individual defendants in criminal proceedings. The focus of the challenge could be a recently introduced statute, but it could equally be a statute of long standing, where constitutional ‘doubt’ is raised as part of the defence strategy of an accused person.

We set our parameters in this inclusive way for two related reasons. First, it is often impossible to clearly distinguish between cases which have a wider public interest agenda and those which do not. Secondly, our primary aim is to better understand constitutional challenges as an influence on the parameters of the criminal law, and such influences and effects may (or may not) be produced, irrespective of the motivations of the party that asserts constitutional invalidity. It follows that we did not limit the dataset to cases heard by the High Court in its original jurisdiction, but included cases that came to the High Court by way of appeal from a lower court decision.

The primary research tool for identifying eligible cases was the AustLII database. Early searches used the LawCite feature to find all High Court cases referring to particularly notable examples of constitutional challenges to criminal statutes (Kable, Lange v Australian Broadcasting Corporation,[18] Cheatle v The Queen,[19] etc). A broader search was then conducted to find all High Court cases with the catchwords ‘crime’ and ‘constitution’, and their derivatives. This search generated a large number of results. These results were filtered to ensure that only cases meeting the criteria of a criminal law statute as defined involving a constitutional challenge were included in our dataset.[20] These results were then cross-referenced against the same online searches using LexisNexis. These parameters yielded a dataset of 59 decisions (see Appendix 1).

All cases in the dataset were categorised according to:

1. year of decision;

2. originating jurisdiction;

3. type of criminal law statute;

4. type of constitutional invalidity asserted; and

5. outcome.

The first two categories are self-explanatory.[21] The other three will be explained briefly. By ‘type of criminal law statute’ we mean the way in which the statute impacted on some aspect of criminal investigation and police powers, criminal trial procedure, criminal responsibility or offence definition, or punishment or other forms of detention/liberty deprivation. We produced a typology for the ‘type of criminal law statute’ category including (in alphabetical order): anti-corruption; conduct of criminal trials (including trial by jury); control orders/association restrictions; electoral matters; immigration matters; military justice; preventive detention; proceeds of crime; public order and police powers; and miscellaneous offence creation.

By ‘type of constitutional invalidity asserted’ we mean: what ground(s) were relied upon in an attempt to impugn the criminal law statute in question? That is, in the Australian context where the only constitutional limitation expressly directed at the administration of criminal justice is section 80 of the Constitution (guaranteeing trial by jury for Commonwealth indictable offences),[22] what section or principle contained in the Constitution did the applicant[23] allege was contravened by the legislation in question? Examples include violation of the principle of ‘institutional integrity’ in Chapter III of the Constitution;[24] section 109 inconsistency of a state law with a Commonwealth law;[25] enactment of a law beyond the Commonwealth’s enumerated heads of powers under section 51; and infringement of the implied freedom of communication on political matters.[26] We did not predetermine or preselect which constitutional grounds were worth examining, but rather, engaged in an open-ended inquiry to identify the ground that has been relied upon. Therefore, although it is qualitatively different from, for instance, the implied ‘institutional integrity’ principle, we included cases in which section 80 was the constitutional touchstone for a challenge. Section 80 has a long history of literal/narrow interpretation and even its potential application is limited to one aspect of criminal law and procedure, that is, trial by jury. Nonetheless, we considered it appropriate to include in our study cases in which the constitutional validity of a statute was challenged on the basis of an assertion that it violated section 80.[27]

Finally, in identifying the ‘outcome’ of a decision, our primary concern was to establish whether or not the legislation in question had been held to be constitutionally valid or invalid. However, in addition, we sought to identify cases in which the applicant had been successful without the High Court ruling on the question of constitutional validity, such as by preferring a statutory construction that supported the applicant’s contention. Therefore, a three-part typology was used for cataloguing the ‘outcome’ of cases for initial quantitative analysis purposes:

1. applicant succeeds – legislation found to be constitutionally invalid;

2. applicant succeeds – other grounds; and

3. applicant fails – legislation found to be constitutionally valid.

A brief summary of dataset characteristics is presented in Part III. As noted above, we recognise that a simple quantitative assessment of ‘success’/‘failure’ in relation to High Court challenges involving criminal law statutes is of limited utility. To facilitate a more nuanced exploration of our findings, we have undertaken a qualitative analysis, with a focus on representation of the range of themes and effects raised by the cases in our dataset. The qualitative analysis presented in Part IV includes exploration of the significance and aftermath of particular decisions, as well as examination of a series of cases in which the High Court has examined a particular mode of criminalisation (eg, decisions concerned with legislation establishing post-sentence preventive detention/supervision regimes). Additional data that was gathered for the purpose of qualitative case study analysis involved, where available, information on the relevant government’s response to the decision in question (such as public statements, amending legislation, second reading speeches etc), and, as appropriate, the responses of governments in other Australian jurisdictions.[28]

Table 1 shows the number of criminal law cases involving a constitutional validity challenge, by originating jurisdiction. It would be speculative to attach too much significance to the relative frequency of cases across jurisdictions (given the multiple associated variables), but it is noteworthy that the Commonwealth and New South Wales (‘NSW’) account for 41[29] of all cases (69 per cent) in the review period. This finding invites further research to determine, for instance, whether the high proportion of constitutional matters emanating from these two jurisdictions is associated with a higher volume enactment of criminal law statutes (compared to other Australian jurisdictions) and/or more frequent use of forms of criminalisation that may be regarded as expanding conventional parameters of criminal responsibility or punishment, or eroding procedural limits on the state’s coercive powers.

Figure 1 represents the number of High Court challenges and successful outcomes per year for the 20-year review period. Explaining the relative frequency of constitutional challenges over time is beyond the scope of the current project. It is worth noting, however, that the period from 2009 to 2014 – the busiest six-year period – was a period that saw a revival of the Kable ‘institutional integrity’ doctrine after some years of dormancy.[30] There was also a higher rate of successful challenge to the validity of statutes during this period (five of 25 cases between 2009 and 2014 (20 per cent)),[31] and three successes on other grounds without a finding of invalidity. By contrast, there was only one finding of constitutional invalidity in the 13 years from Kable (1996) to 2008 (Roach v Electoral Commissioner in 2007),[32] with four successes on other grounds without a finding of invalidity during this period.

Table 2 summarises our findings on the most significant categories of criminal law statutes being challenged on constitutional grounds.

Twelve of the 59 cases (20 per cent) involved legislation that governed the conduct of criminal trials. Six of these (10 per cent of total) involved laws governing the jury system. For example, in Brownlee v The Queen,[33] the applicant challenged section 22 of the Jury Act 1977 (NSW) on the basis that it allowed for the continuation of a trial after the death or discharge of a juror. A decision by a jury with fewer than 12 members was found not to breach section 80 of the Constitution.

Other challenged laws relevant to the conduct of criminal trials addressed the rules of evidence,[34] the standard and burden of proof,[35] the practice of issuing guideline judgments,[36] and sentencing.[37]

Ten per cent of cases involved laws concerned with various forms of preventive detention, that is, regimes that provide for the continuing detention of individuals even after they have served their full prison term. For example, in Fardon v Attorney-General (Qld),[38] the High Court upheld the constitutional validity of the Dangerous Prisoners (Sexual Offenders) Act 2003 (Qld).

Ten per cent of cases involved laws that established ‘control order’ regimes and association-based offences designed to interrupt the activities of outlaw motor cycle gangs, other organised crime groups and terrorist organisations.[39] For example, in Wainohu,[40] the High Court found that the Crimes (Criminal Organisations) Control Act 2009 (NSW) was constitutionally invalid. As we discuss below, this was however a rare and short-lived ‘success’ in efforts to interrupt government use of this particular modality of criminalisation.

Although it is not always recognised as a serious site of potential over-criminalisation, given that the available criminal penalties are at the lower end of the spectrum,[41] three of the 59 cases involved legislation governing public order offences and police powers: Coleman v Power,[42] (Vagrants, Gaming and Other Offences Act 1931 (Qld)); Attorney-General (SA) v Adelaide,[43] (by-law under Local Government Act 1934 (SA) and Local Government Act 1999 (SA)); North Australian Aboriginal Justice Agency v Northern Territory,[44] (Police Administration Act 1978 (NT), as amended by the Police Administration Amendment Act 2014 (NT)).

Fourteen per cent of the cases fell outside of these categories, and are grouped together as ‘Other’. They include provisions compelling the removal of fortifications from buildings,[45] the use of criminal intelligence,[46] the extension of a non-parole period,[47] privative clauses,[48] non-publication orders,[49] the attachment of conditions to bail,[50] and rules regarding the collection of evidence.[51]

The breadth of areas covered by the criminal law statutes in our dataset provides further evidence of the importance of taking account of the diversity of ‘modes’ that criminalisation takes. While much criminal law scholarship has focused on over-criminalisation in the form of offence creation, our study found that many of the criminal law statutes that were challenged related to other dimensions of the state’s punitive/coercive authority, including arrest, detention and compulsory examination. It is appropriate that these modalities of extended criminalisation also be subjected to scrutiny in the context of ongoing debate about the legitimate parameters of criminal law and the criminal justice system as a mechanism of public policy.[52]

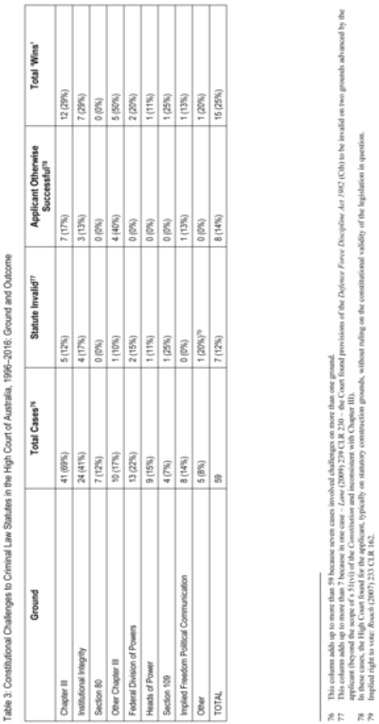

Table 3 summarises our findings on the frequency of, and correlation between, different types of constitutional invalidity arguments and outcomes.

As indicated in that table, in only seven out of 59 cases (12 per cent) did the High Court find the impugned legislation to be constitutionally invalid:

• Kable (1996) 189 CLR 51: Community Protection Act 1994 (NSW) (post-sentence preventive detention);

• Roach (2007) 233 CLR 162:[53] Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (Cth) (restrictions on eligibility of prisoners to vote);

• International Finance Trust (2009) 240 CLR 319: Criminal Assets Recovery Act 1990 (NSW) section 10 (restraining orders preventing dealings with property suspected of being proceeds of crime);

• Lane (2009) 239 CLR 230: Defence Force Discipline Act 1982 (Cth) part VII division 3 (establishment of Australian Military Court);

• Dickson (2010) 241 CLR 491: Crimes Act 1958 (Vic) section 321 (the offence of conspiracy);

• Totani (2010) 242 CLR 1: Serious and Organised Crime (Control) Act 2008 (SA) (control order regime); and

• Wainohu (2011) 243 CLR 181: Crimes (Criminal Organisations) Control) Act 2009 (NSW) (control order regime).

However, in a further eight cases (14 per cent), the applicant succeeded on other grounds, without the High Court ruling on the constitutional validity arguments: McGarry v The Queen;[54] Wong; CEO of Customs v Labrador Liquor; Coleman; Bakewell; Kirk; Minister for Home Affairs v Zentai;[55] X7. For example, in McGarry, the High Court heard an appeal against the imposition of a sentence that included an indefinite detention order under section 98 of the Sentencing Act 1995 (WA). The appeal was upheld, on the basis that the Western Australia Court of Criminal Appeal had erred in construing the legislation. The High Court, therefore, considered it unnecessary to consider the alternative ground that the relevant legislation was constitutionally invalid in light of the ‘institutional integrity’ principle.[56]

In another such case, X7, the plaintiff sought a declaration that the provisions of the Australian Crime Commission Act 2002 (Cth) that require a person to submit to compulsory examination, and which creates a criminal offence of failing to answer questions as required by an Australian Crime Commission examiner, were constitutionally invalid by virtue of inconsistency with Chapter III of the Constitution, including section 80. X7 had been charged with, but not tried for, three serious drug offences under the Criminal Code Act 1995 (Cth). By majority (3:2), the Court found in his favour, without needing to resolve the constitutional validity question. Drawing on the principle of legality, the majority held that division 2 of part II of the Australian Crime Commission Act 2002 (Cth) ‘properly construed, does not permit examination of an accused person about the subject matter of a pending charge’.[57] Central to the majority judgment was that permitting compulsory examination of a person charged with an offence ‘fundamentally alters the process of criminal justice’,[58] and given that there are no such words of express intent, the provisions should be read in conformity with common law rights, privileges and immunities.[59]

When account is taken of these types of ‘wins’, constitutional litigation in the High Court (or, more accurately, litigation in the High Court in which at least one of the grounds asserted is the constitutional invalidity of the legislation in question) was successful in 25 per cent of the cases decided during the 20-year period under review.

Chapter III institutional integrity was the most frequently relied upon ground: 41 per cent of all cases involved a Chapter III institutional integrity argument. This was also the most successful ground: seven ‘wins’ including four invalidity outcomes out of 24 (17 per cent). For example, in Wainohu, the Court found that the control order regime introduced by the Crimes (Criminal Organisations) Control) Act 2009 (NSW) was invalid because the role played under the Act by judges of the Supreme Court of NSW – specifically, the making of a declaration that an organisation was a ‘declared organisation’ without any requirement to give reasons – was incompatible with the principle of institutional integrity.[60] However, the relatively high success rate of Kable/institutional integrity arguments needs to be assessed with caution. For example, the NSW Government’s determination to effect a form of pre-emptive criminalisation by establishing a control order regime directed at outlaw motorcycle gangs was undented by the High Court’s decision in Wainohu in 2011. Rather, the Government introduced a modestly revised version of the legislation into the NSW Parliament – drafted so as to correct the constitutional flaw identified by the High Court – which was duly enacted as the Crimes (Criminal Organisations Control) Act 2012 (NSW). ‘Success’ in the High Court on institutional integrity grounds has rarely been enduring. We elaborate on this finding below.

The guarantee of trial by jury for indictable Commonwealth offences in section 80 of the Constitution was advanced in 12 per cent of the cases in our dataset. For example, in R v LK, the defendant sought to rely upon section 80 to challenge section 107 of the Crimes (Appeal and Review) Act 2001 (NSW), which allowed the Crown to appeal against a directed verdict of acquittal.[61] The applicant in Cheng v The Queen argued that section 233B(1)(d) of the Customs Act 1901 (Cth) was inconsistent with section 80 because it provided for extended imprisonment without the requirement of a jury trial.[62] However, in none of the seven cases in which a section 80 argument was advanced was the legislation found to be invalid.[63]

In addition to the institutional integrity and section 80 grounds, miscellaneous other Chapter III arguments were advanced in 10 cases (17 per cent of total). For example, in Crump v New South Wales,[64] the applicant argued that section 154A of the Crimes (Administration of Sentences) Act 1999 (NSW), which affected the decision to grant parole to serious offenders the subject of non-release recommendations, was invalid because it had the effect of altering the judgment of the Supreme Court of NSW in a ‘matter’ within the meaning of section 73 of the Constitution. In Frugtniet v Victoria,[65] the applicant argued that Chapter III, read as a whole, created a right to a fair trial in criminal proceedings, which would be infringed if she were without legal representation. Although only one of these cases resulted in a finding of constitutional invalidity,[66] the applicant was successful on other grounds in a further four cases. For example, in CEO of Customs v Labrador Liquor, the defendant argued that a civil standard of proof in a criminal trial would be inconsistent with the judicial power conferred by section 71 of the Constitution.[67] The Court found it unnecessary to consider this constitutional argument because, properly construed, the relevant statutes required proof beyond reasonable doubt and not merely on the balance of probabilities.[68]

Despite the relatively high profile that it enjoys in political discourse about ‘constitutional rights’ in Australia, the implied freedom of political communication proved to be an ineffective touchstone for seeking to invalidate criminal law statutes during the review period for the present study. None of the eight implied freedom of communication challenges between 1996 and 2016 (14 per cent of total cases) resulted in a finding of constitutional invalidity, although in one of the cases the Court adopted an interpretation of the relevant legislation that restricted its scope in a way that was favourable to the appellant (ie, a ‘win’ on other grounds).[69]

Table 1: Constitutional Challenges to Criminal Law Statutes in the High Court of Australia, 1996–2016: Originating Jurisdiction

|

Jurisdiction

|

Number of

Cases[70]

|

Proportion of Total Cases (%)

|

|

Australian Capital Territory

|

0

|

0

|

|

Commonwealth

|

29

|

49

|

|

New South Wales

|

12

|

20

|

|

Northern Territory

|

5

|

8

|

|

Queensland

|

7

|

12

|

|

South Australia

|

4

|

7

|

|

Tasmania

|

0

|

0

|

|

Victoria

|

5

|

8

|

|

Western Australia

|

3

|

5

|

In this section of the article we discuss the key findings arising out of our analysis of High Court constitutional challenges to criminal statutes in the 20-year period, 1996–2016.

Before the High Court turns to consider a challenge to constitutional validity, the Court’s first task is to construe the statutory provisions in question.[71] If the matter is resolved in favour of the party asserting constitutional invalidity on non-constitutional grounds (such as by the Court’s endorsement of a particular statutory interpretation), the Court’s practice is to decline to address the asserted constitutional invalidity ground. But it would be misleading to ignore such outcomes in the context of a study of the effectiveness of High Court challenges as a mechanism for addressing over-criminalisation: as noted above, 53 per cent of the 15 ‘wins’ in our dataset were achieved on non-constitutional grounds. Such cases may not produce the ‘knock out’ attention-grabbing effects of cases in which a statute enacted by an Australian legislature is found to be invalid by virtue of inconsistency with the Australian Constitution. Nonetheless, they are an important part of the complex story of how the High Court plays a part in mediating the legitimate limits of criminal law and procedure.

Our primary finding is that the constitutional challenge strategy is a low success rate mode of attempting to curtail the criminal lawmaking parameters of governments. Over the course of 20 years, only seven criminal law statutes have been held by the High Court to be constitutionally invalid – representing just 12 per cent of the 59 cases in our dataset. Acknowledging the limitations of a study of High Court decisions only, over a 20-year period, this finding suggests that, in the absence of a bill of rights and a constitutional framework that empowers the judiciary to invalidate legislation on multiple human rights grounds, there are too few ‘tools’ in the Constitution to provide a strong normative framework for criminal lawmaking. There is often a considerable distance between the reality of the High Court’s mandate for constitutional scrutiny and the aspirations of non-government litigants, particularly where the matter has a significant wider public interest agenda. Objections to criminal law statutes that are often, at heart, normative human rights arguments, cannot be advanced as such, and so are ‘translated’ into a ground of objection that is at least justiciable in the High Court. Some commentators have characterised the most commonly employed constitutional challenge ground over the last 20 years – the Kable institutional integrity principle – as a significant human rights touchstone.[72] However, our findings are consonant with the more sober assessment of constitutional law scholars who have highlighted the limitations of Kable in both protecting human rights[73] and in promoting constructive political dialogue about the human rights implications of proposed expansions of the reach and/or punitive intensity of the criminal law.[74]

In the process of ‘translation’ from human rights grievance to justiciable constitutional question, the normative weight of the original objection is much diminished. High Court justices have themselves commented on the gap to which we are drawing attention here. In Tajjour v New South Wales,[75] in which the High Court rejected an implied freedom of political communication challenge to the constitutional validity of the offence of ‘habitually consorting’ with convicted offenders in section 93X of the Crimes Act 1900 (NSW),[76] Crennan, Kiefel and Bell JJ stated: ‘The desirability of consorting provisions ... is not relevant to the task before the Court’.[77] Similarly, in Kuczborski v Queensland,[78] the High Court rejected a constitutional challenge to a range of anti-bikie criminalisation measures introduced by the Campbell Newman Government.[79] With specific reference to the breadth of powers to declare organisations to be ‘criminal organisations’ (which, in turn, enlivened a number of draconian offences in the Criminal Code 1899 (Qld)), Crennan, Kiefel, Gageler and Keane JJ observed:

It may be accepted that the possible reach of these provisions is very wide, and even that their operation may be excessive and even harsh. But ... to demonstrate that a law may lead to harsh outcomes, even disproportionately harsh outcomes, is not ... to demonstrate constitutional invalidity.[80]

An even more troubling effect of the contortions involved in presenting justiciable constitutional validity issues to the High Court is that a common underlying objective – persuading governments to be more respectful of the human rights implications of their criminal lawmaking practices – is, over time, supplanted by a pragmatic constitutional validity paradigm. One of the cumulative reductive effects of High Court challenges to controversial criminal law statutes is that governments have become preoccupied with constitutional validity rather than due deliberation and consultation about the appropriate limits of the criminal law. As Appleby has observed, scrutiny for compliance with the institutional integrity principle (or, we would add, other constitutional grounds) is a poor substitute for ‘deeper conversations about the role of the state in community protection and acceptable incursions into individual liberties’.[81]

The limitation of constitutional challenge as a strategy for combatting over-criminalisation is illustrated by the sorts of draconian and rights-infringing statutes in our dataset that survived constitutional scrutiny by the High Court. We illustrate this point by discussing three cases: Fardon, Tajjour and NAAJA.

In Fardon, the High Court upheld the constitutionality of the Dangerous Prisoners (Sexual Offenders) Act 2003 (Qld), which provides for the continued detention in prison of individuals who have served their full sentence, if they are assessed as posing a ‘serious danger to the community’.[82] In 2010, the United Nations Human Rights Committee found that the Queensland preventive detention regime was inconsistent with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights[83] prohibitions on arbitrary detention (article 9) and retroactive infliction of punishment (article 15) and the right to a fair trial (article 14).[84] Nonetheless, post-sentence preventive detention regimes for sex offenders are now a ‘standard’ feature of/adjunct to criminal justice systems in multiple Australian jurisdictions.[85] Some jurisdictions have extended preventive detention to a person convicted of other violent crimes,[86] and in 2016 the Australian Parliament established a post-sentence preventive detention regime for ‘high-risk’ persons convicted of terrorism offences.[87]

In Tajjour, the Court upheld the constitutionality of the consorting offence defined by section 93X of the Crimes Act 1900 (NSW) – an offence which carries a penalty of three years’ imprisonment, which can be committed by individuals without criminal records, and where there is no requirement to establish that the communications with individuals with a previous conviction for an indictable offence were for the purpose of planning or conducting criminal activity. The NSW Ombudsman has highlighted the troubling ways in which the broadly drawn legislation impacts on marginalised groups (including Indigenous persons, people experiencing homelessness and young people) who have no association with the sort of organised crime groups at which the legislation was said to be directed.[88]

In NAAJA, the High Court upheld (6:1) the constitutionality of the Northern Territory’s ‘paperless arrest’ regime, which was added to the Police Administration Act 1978 (NT) by the Police Administration Amendment Act 2014 (NT). The amending Act inserted division 4AA which extended police powers to arrest a person without a warrant where the police officer believes ‘on reasonable grounds that the person had committed, was committing or was about to commit, an offence that is an infringement notice offence’.[89] A person can be held in custody under these new powers for a period of up to four hours[90] or if the person is intoxicated ‘for a period longer than four hours until the member believes on reasonable grounds that the person is no longer intoxicated’.[91] The power is potentially exercisable in a wide range of situations both because of the breadth of minor offences defined as an ‘infringement notice offence’[92] and the high volume nature of such offences. It has also been disproportionately used against Aboriginal people.[93]

The High Court found, however, that division 4AA did not confer an ‘unfettered discretion’[94] to hold a person for the four hours instead interpreting the power as subject to the normal constraints on arrest – namely, that the person must as soon as reasonably practicable be released, granted bail or brought before a justice or a court. The four hours was merely a ‘cap’ on what is ‘reasonably practicable’.[95] As such, the power was not penal or punitive and did not interfere with the institutional integrity of the Northern Territory courts.

From a strictly legal point of view, the High Court’s interpretation of the provisions narrowed their potential scope. It could thereby be seen as a kind of ‘win’ for the plaintiffs – albeit a costly one[96] – even though the Court found against them, with the regime being upheld as constitutionally valid. However, the High Court’s decision – and hence the narrowing effect of the interpretation – is not ‘self-executing’ when it comes to the operational scope of the power. Unless police practices change to conform with this interpretation – and away from practices previously adopted[97] – the decision, at best, may provide a reference point for detecting, criticising and disputing possible misuses of the power.

A broader issue highlighted by NAAJA is that choosing to pursue the strategy of constitutional litigation to invalidate a statute tends to lock the parties into ‘extreme’ positions, which may ultimately be contrary to their interests or those of their clients. Thus, the plaintiff may be disposed to assert an expansive operation of the statute to maximise the prospects that it will be held to have overreached its constitutional limits.[98] On the other hand, the party seeking to support validity typically advances a benign construction of the scope of the legislation (to ‘shrink’ the target) – even if, in practice, such an interpretation would make the regime less efficacious than the construction embraced by the challenger.[99]

For example, in NAAJA the plaintiffs argued that division 4AA of the Police Administration Act 1978 (NT) gave the police an unfettered discretion to arrest and detain a person for four hours – or longer where intoxicated. Advocating such an interpretation was a ‘high-stakes’ approach – had the law been found valid and that interpretation endorsed by the Court. As Keane J stated, other persons affected by the statute, ‘whose interests would be advanced in a practical way by a narrower interpretation of the statute, are pre-empted, without being heard, in the single-minded pursuit by the plaintiff of the constitutional issue’.[100] Keane J gave the example of a person claiming damages for false imprisonment, who may want to plead the absence of investigation by police of the strength of the case against him/her while in detention to demonstrate the detention was not for the purposes of investigating an offence.[101] Conversely, the Northern Territory Government argued for a limited and benign construction which clearly ran contrary to the purpose of introducing the power so well, as explained by Gageler J in dissent.[102] In relation to the latter, however, there is nothing locking the Government into such a position if the statute is found to be valid. The forensic purpose of the proffered interpretation is to avoid invalidity. If ‘successful’, there is little to prevent the statute subsequently being given a broader operational interpretation, particularly in contexts like the exercise of police powers, where exposure to supervisory review by the courts is limited in practice.[103]

Tajjour (discussed above) also illustrates another risk associated with the pursuit of High Court challenges. Where an application fails and the High Court rules that a controversial criminal law statute is constitutionally valid, governments can characterise the decision as confirmation and vindication of the legitimacy of their use of criminalisation as a public policy tool. For example, following the High Court’s decision in Tajjour, the NSW Attorney-General and Police Minister issued a joint media statement declaring that the High Court had given the ‘green light to consorting laws’.[104] Similarly, following Kuczborski (discussed above), the Queensland Attorney General said: ‘The Government’s strong stance against organised crime has been fair and effective and that has been confirmed by the High Court today’.[105] These examples reinforce the point, advanced earlier, that one of the effects of the rise to prominence of High Court challenges as a (speculative) ‘brake’ on criminalisation, is that constitutional validity is increasingly seen (inaccurately but powerfully) as a proxy for normative legitimacy.

Another important insight offered by this study is that even where a High Court challenge is ‘successful’, the benefits (that, is the wider benefits, beyond the immediate interests of the affected non-government party) may be short-lived. In a number of instances, a High Court ruling that a particular statute was invalid only briefly interrupted the relevant government’s underlying criminalisation-expanding policy. More than that, the Court’s judgment provided a useful catalogue of constitutional flaws which governments could remedy by way of new or amending legislation. The phenomenon is well illustrated by the series of cases concerning anti-bikie control order regimes decided between 2010 and 2014.

Early iterations of control order regimes were struck down by the High Court on Chapter III institutional integrity grounds. In Totani, the High Court invalidated that part of Australia’s first bikie control order legislation – the Serious and Organised Crime (Control) Act 2008 (SA) – that required the Magistrates Court of South Australia, upon the application of the Commissioner of Police, to make a control order against a member of an organisation that had been deemed a ‘declared organisation’ by the Attorney-General. This (no discretion) model was regarded as a threat to the institutional integrity of the Magistrates Court, a court that exercised federal jurisdiction.[106] In Wainohu, the High Court invalidated the NSW Parliament’s first attempt at establishing a bikie control order regime – the Crimes (Criminal Organisations Control) Act 2009 (NSW) – also on Chapter III grounds. The Court found that the Act was incompatible with the institutional integrity of the Supreme Court of NSW because it provided that a judge could declare an organisation to be a declared organisation (which would, in turn, allow control orders to be made against individual members of the organisation) without having to give reasons.[107]

In 2012, in order to ‘fix’ the defects identified by the High Court, the South Australian Parliament introduced amending legislation[108] and the NSW Parliament introduced replacement legislation.[109]

In 2013, in Assistant Commissioner Condon v Pompano Pty Ltd,[110] the High Court found Queensland’s bikie control order legislation to be constitutionally valid. The focus in this High Court challenge was on those parts of the Criminal Organisation Act 2009 (Qld) that dealt with the role of the Supreme Court of Queensland in hearing an application as to criminal intelligence. When the Queensland legislation came through the High Court challenge process unscathed, governments in other jurisdictions were quick to regard it as the ‘best’ model of bikie control order legislation. In 2013, both NSW[111] and South Australia[112] made further minor amendments to their regimes, with features borrowed from Queensland. At the time, the Attorney-General of South Australia said:

A recent unsuccessful challenge to Queensland’s organised crime laws has meant that other states have brought their laws into line with Queensland’s legislation, ... These circumstances mean that it would be prudent for South Australia to follow suit.[113]

We return to the interstate ‘borrowing’ element of this story, below.

In an ironic final chapter of the evolution of bikie control order regimes in Australia, it appears that despite the considerable energy that has been engaged in introducing, challenging, defending, ‘improving’ and consolidating the respective legislative frameworks across the country, the laws have never been used to restrict the movements or associations of an outlaw motorcycle gang member. In 2016, the NSW Ombudsman completed a review of the operation of the Crimes (Criminal Organisations Control) Act 2012 (NSW). It found that

[d]espite the concerted efforts of a dedicated unit within the Gangs Squad of the NSW Police Force, which spent over three years preparing applications in preparation for declarations under the 2012 Act, no application has yet been brought to Court. As a result, no organisation has been declared to be a criminal organisation under the scheme.[114]

The NSW Police Force advised that it had ceased preparing applications in 2015. The Act’s procedural requirements were regarded as ‘onerous, resource‑intensive, and involv[ing] difficulties that ultimately prevented police making an application to the Court’,[115] and police preferred to employ other powers at their disposal for addressing the activities of outlaw motorcycle gangs and other organised crime groups (including the offence of consorting under section 93X of the Crimes Act 1900 (NSW)). The Ombudsman further reported that ‘[p]olice in other states and territories have experienced similar difficulties in successfully implementing comparable legislation. No declarations have been made in relation to any organisations’.[116]

The story of the role of High Court challenges in the emergence and spread of preventive detention and supervision regimes across Australia has followed a similar pattern to that of anti-bikie control order regimes (though, as we will note below, preventive detention/supervision orders have been much more widely used in practice). Following Kable, in which the High Court invalidated the Community Protection Act 1994 (NSW) on Chapter III institutional integrity grounds, governments became adept at drafting legislation to establish post-sentence preventive detention regimes in such a way as to ensure constitutional validity. Of the five post-Kable challenges to preventive detention legislation in which the High Court has ruled on the constitutional validity of the legislation in question, all have failed.[117]

In contrast to anti-bikie control order regimes, where constitutional validity turned out to be a largely symbolic victory for governments, the validation of preventive detention and supervision order for serious sex offenders and violent offenders has had tangible effects. They are regularly used regimes. For example, in NSW in 2015–16, nine people were in custody pursuant to a Continuing Detention Order and as at 30 June 2016, 55 people were subject to an Extended Supervision Order.[118]

‘Success’ on non-constitutional grounds can also be short-lived, and may nevertheless lead to the consideration or implementation of an even more draconian criminalisation response. The benefit for the successful party may also be very limited. For example, in Wong, the High Court found by majority,[119] that the NSW Court of Criminal Appeal (‘NSWCCA’) did not have jurisdiction to ‘promulgate’ a numerical guideline judgment (applicable to future cases) for the offences of importing heroin and cocaine.[120] It was therefore unnecessary to determine the constitutional validity of the provisions of the Criminal Appeal Act 1912 (NSW) under which the NSWCCA heard and ruled on the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions’ appeal in the case in question.[121] While the High Court did not quash the guideline judgment, having found it was not the subject of an order by the NSWCCA,[122] the Court’s decision nevertheless raised considerable doubt about the validity of guideline judgments, particularly ‘numerical’ guideline judgments. The legislature moved swiftly to remedy the problem. Just over a month after the High Court handed down its decision in Wong the NSW Parliament passed fully operational legislation[123] that expressly conferred jurisdiction retrospectively on the NSWCCA to issue such guidelines.[124] The amending Act authorised the NSWCCA to deliver guideline judgments on its own motion in any proceedings, whether or not it was necessary for the purpose of determining the proceedings (by inserting section 37A into Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act 1999 (NSW)) and also validated previous guidelines.[125]

The controversial concept of ‘guideline judgments’ was central to the appellants obtaining leave to appeal their sentences to the High Court – via a challenge to their constitutional validity – and a focus of High Court criticism in relation to criminalisation and punishment. However, it had little to do with the appellants’ primary concern: the length of the sentence imposed by the NSWCCA. Indeed, in sentencing the appellants for being knowingly concerned in the importation of heroin (not less than the commercial quantity), the NSWCCA did not apply the guideline to the appellants. However, the NSWCCA did increase the sentences originally imposed in the NSW District Court, from 12 years (non-parole period of seven) to 14 years (non-parole period of nine years).[126] The appellants ‘won’ in the High Court, but the Court’s ‘remedy’ was to set aside the orders of the NSWCCA, and to order that the matters be ‘remitted to that Court for further consideration’.[127] Back in the NSWCCA, Sully J once again allowed the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions’ appeal, finding the sentences originally imposed in the NSW District Court to be manifestly inadequate.[128] His Honour increased the head sentence by two years, to 14 years – just as the NSWCCA had done first time round – but only increased the non-parole period by one year, to eight years.[129] Therefore, the net benefit that accrued to the appellants in Wong was a one-year reduction in their minimum term of imprisonment. Meanwhile, as discussed above, the High Court litigation triggered NSW legislation that consolidated the place of guideline judgments in NSW sentencing law and practice.[130]

Finally, Wong also exemplifies a further risk associated with pursuing constitutional challenges in the High Court: the spectre of ‘defeat’ may prompt a government to consider an even more draconian criminalisation response than had been produced by the challenged legislation. Shortly after the High Court’s judgment in Wong, the then Premier, Bob Carr, announced that if the High Court invalidated guideline judgments he would move to introduce mandatory minimum sentencing.[131]

The NSW Government’s response to X7, discussed above, and subsequent decisions of the High Court concerned with compulsory examination by the NSW Crimes Commission,[132] illustrate a further variation on how government ‘losses’ can be managed so as to minimise the restrictions effected by the High Court’s ruling. The Crime Commission Legislation Amendment Act 2014 (NSW) amended the Crime Commission Act 2012 (NSW) to ‘restore confidence in the lawful and appropriate exercise of the commission’s functions’ after ‘a series of cases in the High Court ... [had] thrown into doubt the use of compulsory examination powers’.[133] The Police Minister described the High Court’s decisions as recognition that ‘it is within the power of the Legislature to create laws that depart from the fundamental principles of our system of justice’, but Parliament’s ‘intention must be “expressed clearly or in words of necessary intendment”’.[134] The 2014 amendments were designed to ‘incorporate those clear “words of necessary intendment”’.[135] The Minister said:

The amendments aim to protect the use of the commission’s compulsory examination powers and the admissibility of evidence obtained in or derived from these commission hearings and to protect criminal prosecutions from challenge solely on the basis that a person has been questioned by the commission.[136]

In this instance, the NSW Government’s response to the High Court’s rulings involved not only a complex legislative ‘fix’,[137] but also ‘Chinese wall’-style operational changes. These include the use of discrete teams of investigators and lawyers to ensure that a ‘clean team’[138] is responsible for criminal prosecutions without having been ‘tainted’ by exposure to evidence, gathered via compulsory examination in the NSW Crime Commission, that would be prejudicial to the accused (such as self-incriminatory statements).

Against the backdrop of a long practice of executive governments seeing benefit in ‘[cloaking] their policies in the legitimacy of the courts’,[139] one of the lessons learned by governments as a result of constitutional challenges post-Kable is that, in some contexts at least, there may be benefits in keeping the courts out of the exercise of controversial extended criminalisation regimes. In Fardon, Gleeson CJ alluded to this issue in the context of a challenge to Queensland’s preventive detention regime. The Chief Justice expressed surprise that ‘there would be an objection to having detention decided upon by a court, whose proceedings are in public, and whose decisions are subject to appeal, rather than by executive decision’.[140] Of course, this is a (perverse) consequence of the fact that the Kable institutional integrity principle is one of the very few grounds on which the constitutional validity of legislation might be impugned. Kable principle arguments are enlivened by concern for the institutional integrity of courts, not other arms of government. Lawmakers may effectively ‘neutralise’ the most powerful invalidity tool (in a limited toolbox) by keeping the courts out of legislative regimes altogether. This may further weaken the efficacy of constitutional challenges as a constraint on criminal lawmaking.

That this may be one of the lessons learned from the High Court’s post-Kable constitutional validity jurisprudence was also noted in NAAJA. Gageler J, in dissent, found the relevant provisions of the Police Administration Act 1978 (NT) (discussed above) constitutionally invalid on the basis that they made the NT courts ‘support players in a scheme the purpose of which is to facilitate punitive executive detention’.[141] As Gageler J stated, however, the flow-on reality is:

Were the provisions which contemplate a role for courts to be removed, the legislative scheme of Div 4AA would appear to be quite different. The legislative scheme would be starkly one of catch and release. The scheme would be reduced so as to appear on the face of the legislation implementing it to be one which authorises police to detain, and then release, persons arrested without warrant on belief of having committed or having been about to commit an offence. The political choice for the Legislative Assembly would be whether or not to enact a scheme providing for deprivation of liberty in that stark form.[142]

A recent illustration that governments may have ‘started to turn away from the courts and towards non-judicial bodies’ to exercise significant decision-making functions,[143] is part 6B of the Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002 (NSW), as amended by the Criminal Legislation Amendment (Organised Crime and Public Safety) Act 2016 (NSW). This amendment authorises a senior police officer to make a public safety order banning a person from attending designated events or locations (for up to 72 hours) where that person’s presence is considered to pose ‘a serious risk to public safety or security’. Contravention of a public safety order is a criminal offence that carries a penalty of five years’ imprisonment.[144]

Ironically then, one of the longer-term effects of the prominent part that Chapter III institutional integrity arguments has played in constitutional challenges over the last 20 years is that governments may be even less encumbered by normative considerations in their deployment of expanded criminalisation responses to ‘new’ harms, risks and uncertainties.

One of the effects of the spectre of High Court constitutional challenges to criminalisation legislation in the post-Kable era is that policy formulation and lawmaking processes now routinely involve focused ‘pre-drafting’ consideration of potential constitutional questions. In all states and territories in the normal course where legislative provisions potentially raise constitutional issues, the relevant attorney-general (or other minister responsible) will usually seek the advice of their solicitor-general and/or the relevant Crown Solicitor’s Office. Such advice may identify provisions that are susceptible to constitutional challenge and suggest revision – or possibly even abandonment – of the proposed law prior to enactment.[145] There is also scope for pre-enactment examination through parliamentary scrutiny committees that exist in various forms in all Australian jurisdictions.[146]

Where legislators borrow from legislation enacted in another state/territory, the later legislative regimes may have ‘learnt the lessons’ of an earlier constitutional flaw – hence the incremental development of such regimes may impact on constitutional challenges. Longer term, the accumulation of cases/jurisprudence from the High Court, and lessons learned across jurisdictions in Australia’s federation, have effectively provided state/territory governments with a guide to the contours of the (modest) constitutional restrictions on their criminal lawmaking powers.

Whether such inter-jurisdictional borrowing practices are a desirable by-product of the phenomenon of High Court challenges to the validity of criminalisation statutes is a moot point. In an Australian federal constitutional environment where criminal lawmaking is primarily the preserve of state and territory governments, the goal of greater national harmonisation of Australian criminal laws has a long history.[147] An aspect of the constitutional challenge strategy which may be lost by focusing only on case/statute-specific ‘wins’ and losses’ is the role that these High Court decisions can play in harmonising or ‘unifying’ Australian criminal lawmaking practices.[148] Constitutional challenges create an opportunity for all state and territory governments and the Commonwealth Government to intervene in matters before the High Court, and express views about the impugned legislation. Interveners may be motivated by a desire to pre-emptively ‘defend’ similar legislation already in place in the intervening jurisdiction, which has not yet been the subject of a constitutional challenge. Alternatively, the motivation may be to attempt to ensure that the intervening jurisdiction remains free, in the future, to enact legislation of the sort that has been constitutionally challenged.

In addition, as noted above, all Australian governments have the opportunity to ‘learn lessons’ from the High Court’s decisions. It is appropriate to acknowledge then, the role that High Court constitutional challenges can play[149] in achieving at least some of the goals of the protracted movement for adoption of a model criminal code in Australia.[150] However, there is a danger that governments may ‘borrow’ a regime from other jurisdictions because it has passed constitutional muster, rather than because it has been shown to be a well-adapted, effective and proportionate response to the crime problem at which it is directed.[151] Worse still, governments may be emboldened to enact draconian or over-criminalising legislation[152] because of the ‘success’ of governments in other states and territories when defending such laws before the High Court.

Our analysis shows that attempts to invoke the judicial authority of the High Court to invalidate criminal laws on constitutional grounds have rarely been successful over the last 20 years. Even rare ‘wins’ have done little to rein in over-criminalisation in the medium and longer-terms. Governments have become adept at responding to invalidity rulings with ‘new and improved’ Constitution-compliant amending legislation, such that, ironically, High Court challenges may strengthen rather than undercut the controversial criminalisation policy in question. The cumulative effect of the constitutional jurisprudence that High Court challenges have generated over the last two decades is that lawmakers in all Australian jurisdictions have learned (from cases emanating from their own jurisdiction as well as lessons learned from others) how best to pursue controversial extensions of criminalisation (including by restricting due process and fair trial protections) while managing the risk of judicial invalidation.

The strategy of challenging controversial criminalisation statutes in the High Court is not entirely without merit. In addition to the specific instances in which non-government applicants achieve the personal benefit or protection that they aimed to achieve via litigation, wider positive public interest effects may be produced. For instance, publicity surrounding a decision can draw attention to a problem of over-criminalisation that had previously lacked visibility (such as NAAJA’s challenge to the legislation establishing the Northern Territory’s ‘paperless arrest’ regime), or garner support for the pursuit of other strategies to address the perceived problem. Further socio-legal research could usefully examine constitutional challenges as a form of legal mobilisation or public interest litigation.[153] A valuable line of inquiry would be to investigate the motivations and strategies that have informed decisions to challenge legislation in the High Court in particular instances, including why parties may see value in constitutional litigation even where the prospect of having the legislation struck down is known to be low.

We have previously argued[154] that the reasons why pre-enactment scrutiny of criminal law bills by parliamentary committees is ineffective as a mechanism for checking over-criminalisation include the modest authority of scrutiny committees, and the fact that scrutiny occurs too late in the lawmaking process. Typically, by the time such committees express a view about the merits of a bill, the political die has already been cast – in the Cabinet and/or party room. Belated post-enactment evaluation is also one of the weaknesses of the High Court constitutional challenge strategy, combined with the very limited grounds available for attempting to impugn criminal law statutes. It is clear that proponents for more principled criminal lawmaking need to develop strategies for much earlier intervention in the political debates out of which controversial criminalisation policies and legislative changes often emerge. This, of course, is no small task. However, it is clear that the surest path to discouraging over-reliance on excessively punitive and human rights-diminishing modalities of criminalisation[155] is to interrupt the political urge to enact such laws in the first place.

• Langer v Commonwealth [1996] HCA 43; (1996) 186 CLR 302

• Kable v Director of Public Prosecutions (NSW) [1996] HCA 24; (1996) 189 CLR 51

• Leask v Commonwealth [1996] HCA 29; (1996) 187 CLR 579

• Levy v Victoria [1997] HCA 31; (1997) 189 CLR 579

• Frugtniet v Victoria (1997) 148 ALR 320

• Nicholas v The Queen [1998] HCA 9; (1998) 193 CLR 173

• Re Colina; Ex parte Torney [1999] HCA 57; (1999) 200 CLR 386

• Cheng v The Queen [2000] HCA 53; (2000) 203 CLR 248

• Brownlee v The Queen [2001] HCA 36; (2001) 207 CLR 278

• McGarry v The Queen [2001] HCA 62; (2001) 207 CLR 121

• Wong v The Queen [2001] HCA 64; (2001) 207 CLR 584

• Pasini v United Mexican States (2002) 209 CLR 246

• Fittock v The Queen [2003] HCA 19; (2003) 217 CLR 508

• Ng v The Queen [2003] HCA 20; (2003) 217 CLR 521

• Chief Executive Officer of Customs v Labrador Liquor Wholesale Pty Ltd (2003) 216 CLR 161

• Putland v The Queen [2004] HCA 8; (2004) 218 CLR 174

• Silbert v Director of Public Prosecutions (WA) [2004] HCA 9; (2004) 217 CLR 181

• Truong v The Queen [2004] HCA 10; (2004) 223 CLR 122

• Behrooz v Secretary, Department of Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs [2004] HCA 36; (2004) 219 CLR 486

• Coleman v Power [2004] HCA 39; (2004) 220 CLR 1

• Re Colonel Aird; Ex parte Alpert (2004) 220 CLR 308

• Baker v The Queen [2004] HCA 45; (2004) 223 CLR 513

• Fardon v Attorney-General (Qld) [2004] HCA 46; (2004) 223 CLR 575

• Dalton v NSW Crime Commission [2006] HCA 17; (2006) 227 CLR 490

• Theophanous v Commonwealth [2006] HCA 18; (2006) 225 CLR 101

• XYZ v Commonwealth [2006] HCA 25; (2006) 227 CLR 532

• Vasiljkovic v Commonwealth [2006] HCA 40; (2006) 227 CLR 614

• White v Director of Military Prosecutions [2007] HCA 29; (2007) 231 CLR 570

• Thomas v Mowbray [2007] HCA 33; (2007) 233 CLR 307

• Roach v Electoral Commissioner [2007] HCA 43; (2007) 233 CLR 162

• Gypsy Jokers Motorcycle Club Inc v Commissioner of Police (2008) 234 CLR 532

• R v Tang [2008] HCA 39; (2008) 237 CLR 1

• K-Generation Pty Ltd v Liquor Licensing Court [2009] HCA 4; (2009) 237 CLR 501

• Bakewell v The Queen [2009] HCA 24; (2009) 238 CLR 287

• Lane v Morrison [2009] HCA 29; (2009) 239 CLR 230

• International Finance Trust Co Ltd v NSW Crime Commission (2009) 240 CLR 319

• Kirk v Industrial Court (NSW) (2010) 239 CLR 531

• R v LK (2010) 241 CLR 177

• Dickson v The Queen (2010) 241 CLR 491

• South Australia v Totani [2010] HCA 39; (2010) 242 CLR 1

• Hogan v Hinch [2011] HCA 4; (2011) 243 CLR 506

• Wainohu v New South Wales (2011) 243 CLR 181

• Haskins v Commonwealth (2011) 244 CLR 22

• Momcilovic v The Queen (2011) 245 CLR 1

• Wotton v Queensland (2012) 246 CLR 1

• Crump v New South Wales [2012] HCA 20; (2012) 247 CLR 1

• Minister for Home Affairs (Cth) v Zentai [2012] HCA 28; (2012) 246 CLR 213

• Attorney-General (SA) v Adelaide [2013] HCA 3; (2013) 249 CLR 1

• Monis v The Queen (2013) 249 CLR 92

• Assistant Commissioner Condon v Pompano [2013] HCA 7; (2013) 252 CLR 38

• Maloney v The Queen (2013) 252 CLR 168

• X7 v Australian Crime Commission [2013] HCA 29; (2013) 248 CLR 92

• Magaming v The Queen [2013] HCA 40; (2013) 252 CLR 381

• Attorney-General (NT) v Emmerson (2014) 307 ALR 174

• Pollentine v Bleijie [2014] HCA 30; (2014) 253 CLR 629

• Tajjour v New South Wales [2014] HCA 35; (2014) 254 CLR 508

• Kuczborski v Queensland [2014] HCA 46; (2014) 254 CLR 51

• Duncan v Independent Commission Against Corruption [2015] HCA 32; (2015) 256 CLR 83

• North Australian Aboriginal Justice Agency Ltd v Northern Territory [2015] HCA 41; (2015) 256 CLR 569

• Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (Cth)

• Community Protection Act 1994 (NSW)

• Financial Transaction Reports Act 1988 (Cth)

• Wildlife (Game) (Hunting Season) Regulations 1994 (Vic), made under Wildlife Act 1975 (Vic), and Conservation, Forests and Lands Act 1987 (Vic)

• Crimes Act 1958 (Vic)

• Crimes Act 1914 (Cth); Customs Act 1901 (Cth)

• Family Law Act 1975 (Cth)

• Customs Act 1901 (Cth)

• Jury Act 1977 (NSW)

• Sentencing Act 1995 (WA); Sentencing Administration Act 1995 (WA)

• Criminal Appeal Act 1912 (NSW)

• Extradition Act 1988 (Cth)

• Criminal Code Act 1983 (NT); Juries Act 1962 (NT)

• Juries Act 1967 (Vic)

• Customs Act 1901 (Cth); Excise Act 1901 (Cth)

• Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth); Sentencing Act (NT)

• Crimes (Confiscation of Profits) Act 1988 (WA); Criminal Property Confiscation (Consequential Provisions) Act 2000 (WA)

• Extradition Act 1988 (Cth); Crimes Act 1958 (Vic)

• Migration Act 1958 (Cth)

• Vagrants, Gaming and Other Offences Act 1931 (Qld)

• Defence Force Discipline Act 1982 (Cth)

• Sentencing Act 1989 (NSW); Sentencing Legislation Further Amendment Act 1997 (NSW)

• Dangerous Prisoners (Sexual Offenders) Act 2003 (Qld)

• Service and Execution of Process Act 1992 (Cth)

• Crimes (Superannuation Benefits) Act 1989 (Cth)

• Crimes Act 1914 (Cth)

• Extradition Act 1988 (Cth)

• Defence Force Discipline Act 1982 (Cth)

• Criminal Code Act 1995 (Cth); Terrorism (Commonwealth Powers) Act 2003 (Vic)

• Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (Cth)

• Corruption and Crime Commission Act 2003 (WA)

• Criminal Code Act 1995 (Cth)

• Liquor Licensing Act 1997 (SA)

• Sentencing (Crime of Murder) and Parole Reform Act 2003 (NT)

• Defence Force Discipline Act 1982 (Cth)

• Criminal Assets Recovery Act 1990 (NSW)

• Industrial Relations Act 1996 (NSW)

• Crimes (Appeal and Review) Act 2001 (NSW)

• Crimes Act 1958 (Vic)

• Serious and Organised Crime (Control) Act 2008 (SA)

• Serious Sex Offenders Monitoring Act 2005 (Vic)

• Crimes (Criminal Organisations Control) Act 2009 (NSW)

• Military Justice (Interim Measure) Act (No 2) 2009 (Cth)

• Drugs, Poisons and Controlled Substances Act 1981 (Vic); Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 (Vic)

• Corrective Services Act 2006 (Qld)

• Crimes (Administration of Sentences) Act 1999 (NSW)

• Extradition Act 1988 (Cth)

• Corporation of the City of Adelaide, By-Law No 4 – Roads (at 31 May 2011)

• Criminal Code Act 1995 (Cth)

• Criminal Organisation Act 2009 (Qld)

• Liquor Act 1992 (Qld); Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth)

• Australian Crime Commission Act 2002 (Cth)

• Migration Act 1958 (Cth)

• Criminal Property Forfeiture Act (Consequential Amendments) Act 2002 (NT); Misuse of Drugs Act (NT); Northern Territory (Self-Government) Act 1978 (Cth)

• Criminal Law Amendment Act 1945 (Qld)

• Crimes Act 1900 (NSW)

• Vicious Lawless Association Disestablishment Act 2013 (Qld); Criminal Code Act 1899 (Qld); Bail Act 1980 (Qld); Liquor Act 1992 (Qld)

• Independent Commission Against Corruption Act 1988 (NSW)

• Police Administration Act 1978 (NT)

[*] Professor and Co-director, Centre for Crime, Law and Justice, Faculty of Law, University of New South Wales.

[**] Associate Professor, School of Law, University of Wollongong.

The authors thank Tom Allchurch for excellent research assistance.

[1] Luke McNamara et al, ‘Theorising Criminalisation: The Value of a Modalities Approach’ (2018) 7(3) International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 91 <https://www.crimejusticejournal.com/article/view/918/681>.

[2] Pat O’Malley, Crime and Risk (Sage Publications, 2010).

[3] Lucia Zedner, ‘Fixing the Future? The Pre-emptive Turn in Criminal Justice’ in Bernadette McSherry, Alan Norrie and Simon Bronitt (eds), Regulating Deviance: The Redirection of Criminalisation and the Futures of Criminal Law (Hart Publishing, 2009) 57.

[4] Nicola McGarrity, ‘From Terrorism to Bikies: Control Orders in Australia’ (2012) 37 Alternative Law Journal 166; Lisa Burton and George Williams, ‘What Future for Australia’s Control Order Regime?’ (2013) 24 Public Law Review 182.

[5] See Heather Douglas, ‘The Shifting Moral Compass: Post-sentence Detention of Sex Offenders in Australia’ (2011) 17 Australian Journal of Human Rights 91.

[6] See, eg, Inclosed Lands, Crimes and Law Enforcement Legislation Amendment (Interference) Act 2016 (NSW); Workplaces (Protection from Protesters) Act 2014 (Tas). On 18 October 2017, the High Court found that provisions of the latter Act were constitutionally invalid because they imposed an impermissible burden on the implied freedom of political communication: see Brown v Tasmania (2017) 349 ALR 398. Note that this decision falls outside the time frame for the present study (1996–2016).

[7] Douglas N Husak, Overcriminalization: The Limits of the Criminal Law (Oxford University Press, 2008).

[8] See, eg, David Brown, ‘Criminalisation and Normative Theory’ (2013) 25 Current Issues in Criminal Justice 605; Luke McNamara, ‘Criminalisation Research in Australia: Building a Foundation for Normative Theorising and Principled Law Reform’ in Thomas Crofts and Arlie Loughnan (eds), Criminalisation and Criminal Responsibility in Australia (Oxford University Press, 2015) 33. Another catalyst for the emergence of theoretical criminalisation scholarship in Australia in recent years has been the work of scholars in the United Kingdom and the United States of America addressing similar patterns and concerns: see, eg, ibid; Nicola Lacey, ‘The Rule of Law and the Political Economy of Criminalisation: An Agenda for Research’ (2013) 15 Punishment & Society 349; R A Duff et al (eds), Criminalization: The Political Morality of the Criminal Law (Oxford University Press, 2014); Andrew Ashworth and Lucia Zedner, Preventive Justice (Oxford University Press, 2014); Nicola Lacey, In Search of Criminal Responsibility: Ideas, Interests, and Institutions (Oxford University Press, 2016); Victor Tadros, Wrongs and Crimes (Oxford University Press, 2017); R A Duff, The Realm of the Criminal Law (Oxford University Press, 2018); Lindsay Farmer, Making the Modern Criminal Law: Criminalization and Civil Order (Oxford University Press, 2016).

[9] Canada Act 1982 (UK) cl 11, sch B pt I.

[10] United States Constitution amends I–X.

[11] See, eg, Luke McNamara and Julia Quilter, ‘Institutional Influences on the Parameters of Criminalisation: Parliamentary Scrutiny of Criminal Law Bills in New South Wales’ (2015) 27 Current Issues in Criminal Justice 21; Luke McNamara, ‘Editorial: In Search of Principles and Processes for Sound Criminal Law-Making’ (2017) 41 Criminal Law Journal 3.

[12] [1996] HCA 24; (1996) 189 CLR 51 (‘Kable’).

[13] See, eg, Rebecca Ananian-Welsh, ‘Kuczborski v Queensland and the Scope of the Kable Doctrine’ [2015] UQLawJl 3; (2015) 34 University of Queensland Law Journal 47; Gabrielle Appleby, ‘The High Court and Kable: A Study in Federalism and Human Rights Protection’ [2014] MonashULawRw 27; (2015) 40 Monash University Law Review 673; Rebecca Ananian-Welsh and George Williams, ‘The New Terrorists: The Normalisation and Spread of Anti-Terror Laws in Australia’ [2014] MelbULawRw 17; (2014) 38 Melbourne University Law Review 362; Jeremy Gans, ‘Current Experiments in Australian Constitutional Criminal Law’ (Paper presented at Australian Association of Constitutional Law, Sydney, 9 September 2014); Suri Ratnapala and Jonathan Crowe, ‘Broadening the Reach of Chapter III: The Institutional Integrity of State Courts and the Constitutional Limits of State Legislative Power’ [2012] MelbULawRw 5; (2012) 36 Melbourne University Law Review 175; Mirko Bagaric, ‘Separation of Powers Doctrine in Australia: De Facto Human Rights Charter’ (2011) 7 International Journal of Punishment and Sentencing 25; J A Devereux, ‘Callinan, the Constitution and Criminal Law: A Decade of Pragmatism’ [2008] UQLawJl 7; (2008) 27 University of Queensland Law Journal 71; Wendy Lacey, ‘Inherent Jurisdiction, Judicial Power and Implied Guarantees under Chapter III of the Constitution’ [2003] FedLawRw 2; (2003) 31 Federal Law Review 57.

[14] Fiona Wheeler, ‘The Rise and Rise of Judicial Power under Chapter III of the Constitution: A Decade in Overview’ (2000) 20 Australian Bar Review 282, 282; see also Wendy Lacey, above n 13, 57.

[15] Wheeler, ‘The Rise and Rise of Judicial Power’, above n 14, 282.