University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

INFORMING THE EUTHANASIA DEBATE: PERCEPTIONS OF AUSTRALIAN POLITICIANS

ANDREW MCGEE,[*] KELLY PURSER,[**] CHRISTOPHER STACKPOOLE,[***] BEN WHITE,[****] LINDY WILLMOTT[*****] AND JULIET DAVIS[******]

In the debate on euthanasia or assisted dying, many different arguments have been advanced either for or against legal reform in the academic literature, and much contemporary academic research seeks to engage with these arguments. However, very little research has been undertaken to track the arguments that are being advanced by politicians when Bills proposing reform are debated in Parliament. Politicians will ultimately decide whether legislative reform will proceed and, if so, in what form. It is therefore essential to know what arguments the politicians are advancing in support of or against legal reform so that these arguments can be assessed and scrutinised. This article seeks to fill this gap by collecting, synthesising and mapping the pro- and anti-euthanasia and assisted dying arguments advanced by Australian politicians, starting from the time the first ever euthanasia Bill was introduced.

Euthanasia attracts continued media, societal and political attention.[1] In particular, voluntary active euthanasia (‘VAE’) and physician-assisted suicide (‘PAS’) remain controversial topics provoking passionate support or opposition. Whether for or against, VAE or PAS (which we will call ‘EAS’ when we mean to refer to both)[2] have a tendency to strongly polarise opinions. This is evident in the arguments advanced by politicians debating proposed legislative reform in Australia.[3] A convergence of factors including high and sustained public support for reform,[4] an ageing and increasingly informed population seeking choices for their end-of-life experience, the changing international landscape, and the regular and sustained legislative reform attempts domestically,[5] makes this issue increasingly difficult for politicians to ignore. Indeed, as recent experience has shown in Victoria with the passing of the Voluntary Assisted Dying Act 2017 (Vic), and with parliamentary committees now established on this issue in Western Australia and the Australian Capital Territory, there may be a shift in the political willingness to grapple with EAS.

Many different arguments have, of course, been advanced either in favour of or against legislative change in the academic literature on this subject. This literature is vast, but very little research has been undertaken to track the politico-legal, as opposed to the academic, landscape – what are the arguments being advanced by politicians in support of, or in opposition to, legal reform when the Bills proposing reform are introduced into Parliament? This article seeks to fill this gap by collecting, synthesising and mapping the pro- and anti-EAS arguments advanced by politicians within Australia over more than two decades from 1993–2017 which are contained in the parliamentary debates surrounding the introduction of the relevant Bill (see Annexure A for a list of these arguments). The year 1993 is our starting point because this is the year the first ever Bill seeking to legalise EAS was introduced in Australia.[6]

Politicians will ultimately decide whether legislative reform will proceed and, if so, in what form. It is their views that will determine the fate of a particular Bill. For this reason, it is critical to identify the arguments that politicians advance in Parliament both supporting and opposing reform. Charting these arguments is important because it provides a comprehensive picture of the reasons that politicians, as the final decision-makers on this issue, regard as important (or at least purport to regard as important). The analysis undertaken in this article can also inform public debate by making transparent the issues that are discussed in Parliaments of Australia when EAS is being considered. This mapping of arguments will allow readers to draw conclusions about their quality, or otherwise help to inform future debate.

We begin by clarifying the terms we use in this article. This is especially important as some terms are often used by different stakeholders in different ways, generating further misunderstanding. We will then outline the methodology we have adopted. A brief overview of the sociopolitical landmarks relating to the arguments underpinning the EAS debate will be provided before exploring those arguments in detail. When discussing the arguments in detail, we will sometimes divide the pro- and con-arguments in a given category. For example, both proponents and opponents of EAS make appeals to the concept of autonomy. We keep the pro- and con-arguments separate to present the clearest picture of the arguments used by each side and avoid the presentation bias involved in stating one position as a thesis and another as merely an objection to that thesis, and not a position in its own right. Not every argument is advanced in this debate as an objection or counter reply to some other argument made in the debate, although some arguments are advanced both as an objection to some other argument and as an argument in its own right. Where the argument is also used as a rebuttal to a pro-argument, we shall also mention that in the presentation of the pro-argument, for completeness. For example, in the ‘arguments against EAS’ section, one argument that we present is the ‘right to life’ argument. Often, in rebuttal of this argument, politicians appeal to what we call the ‘autonomy objection’. We therefore mention this rebuttal argument briefly in presenting the ‘right to life’ argument, even though we cover the ‘autonomy’ argument in more detail when presenting arguments for EAS in the ‘arguments for EAS’ section.

Given that the EAS debate can sometimes be clouded by semantic uncertainty, we will first clarify the terminology we have adopted in this article in the following table.[7]

Table 1: Terminology

|

Term

|

Meaning

|

Example

|

|

Euthanasia

|

For the purpose of relieving suffering, a person performs a lethal

action[8] with the intention of

ending the life of another person

|

A doctor injects a patient with a lethal substance to relieve that person

from unbearable physical pain

|

|

Voluntary active euthanasia (‘VAE’)

|

Euthanasia is performed at the request of the person whose life is ended,

and that person is competent

|

A doctor injects a competent patient, at their request, with a lethal

substance to relieve that person from unbearable physical pain

|

|

Competent

|

A person is competent if he or she is able to understand the nature and

consequences of a decision, and can retain, believe, evaluate,

and weigh

relevant information in making that decision

|

|

|

Non-voluntary euthanasia

|

Euthanasia is performed and the person is not competent

|

A doctor injects a patient in a post-coma unresponsive state (sometimes

referred to as a persistent vegetative state) with a lethal

substance

|

|

Involuntary euthanasia

|

Euthanasia is performed and the person is competent but has not expressed

the wish to die or has expressed a wish that he or she does

not die

|

A doctor injects a competent patient who is in the terminal stage of a

terminal illness such as cancer with a lethal substance without

that

person’s request

|

|

Withholding or withdrawing life-sustaining

treatment[9]

|

Treatment that is necessary to keep a person alive is not provided or is

stopped

|

Withdrawing treatment: A patient with profound brain damage as a result of

a heart attack is in intensive care and breathing with

the assistance of a

ventilator, and a decision is made to take him or her off the ventilator because

there is no prospect of recovery

Withholding treatment: A decision is made not to provide nutrition and

hydration artificially (such as through a tube inserted into

the stomach) to a

person with advanced dementia who is no longer able to take food or hydration

orally

|

|

Assisted suicide

|

A competent person dies after being provided by another with the means or

knowledge to kill him- or herself

|

A friend or relative obtains a lethal substance (such as Nembutal) and

provides it to another to take

|

|

Physician-assisted suicide (‘PAS’)

|

Assisted suicide where a doctor acts as the assistant

|

A doctor provides a person with a prescription to obtain a lethal dose of a

substance

|

|

Voluntary active euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide

(‘EAS’)

|

Voluntary euthanasia or physician assisted suicide

|

The term ‘euthanasia’ is sometimes used more broadly to refer

either to VAE or PAS, or both. We use EAS to capture this

use. Many of the

comments in Hansard do not distinguish between the terms, and the arguments

offered have been applied to both (a

politician might make the same argument

against a VAE Bill and against a later or earlier PAS Bill, or the argument

applied by one

politician to a VAE Bill is applied by another to a PAS Bill, or

the politician may make a point about ‘euthanasia’ in

a Bill that

seeks to legalise both VAE and PAS, or just PAS, or may support an argument

about VAE with a point about PAS). Except

where there has been an express

differentiation in Hansard and the meaning is clear, we use the term

EAS.[10]

|

Legal doctrinal analysis was used to access the relevant Hansard, Bills and legislation. Data was collected by searching all Australian parliamentary debates contained on the government websites of each jurisdiction. Existing annotated Bill collections were used as the foundation for determining the number and descriptive details of each EAS Bill introduced into Parliament throughout Australia.[11] The annotated Bill collections were then supplemented through additional research into parliamentary debates and other records and memoranda, specifically Hansard and Notice Papers. Most jurisdictions examined (details below) provided a fully searchable database through which complete copies of parliamentary debates could be obtained. If fully searchable databases were not provided, electronic indices were used to search for the time periods within which debates occurred. Written records were reviewed if electronic records were unobtainable.

The debates were reviewed and an annotated arguments schedule was prepared specifying each argument advanced by every politician debating the subject matter of EAS in respect of a Bill. Bibliographic details of the debate, including the speaker’s name and the date on which the speech was presented, were identified. A thematic schedule recording the nature and frequency of the arguments was prepared with references to the annotated schedule of arguments. The categories of argument adopted by the research team were iteratively refined over time with reference to the data set. Each category of argument was assigned a numerical identifier (for example ‘(P33)’) and a brief description. Where a single statement by a politician contained several categories of arguments, multiple numerical identifiers were assigned to the statement to accurately reflect its nature. Repeat incidents of a single argument by the same speaker within a single speech were removed to avoid distortion of the data set. Where the same politician presented the same argument across different speeches, the first occasion on which the argument occurred within each speech was recorded. In a small number of cases, Bills went to the Committee stage, where each clause of the Bill is considered in detail. We have included data from the Committee stages for each of these Bills. However, the Committee stage normally involves a number of opponents to the Bill asking questions of the Bill’s sponsor about the specificities of the clause. Most of these comments are too specific to a particular clause to be included in the general arguments for or against, but any general arguments made have been included. Arguments presented within unofficial statements (such as interjections) were removed. Preliminary data analysis occurred simultaneously with the data collection to ensure that the correct classification of data was occurring. A thematic approach was adopted because it facilitated the systematic content analysis and identification of the main themes, best achieving the aim of analysing the publicly recorded arguments advanced by politicians in the EAS debate.

The limitations of the research must be acknowledged. As with all research, there is an issue of researcher error and bias; some degree of subjectivity is inevitable, for example in relation to how the data was collected, collated and interpreted. The authors sought to recognise the subtle distinctions between different categories of arguments and only combined the statements where the argument was substantially the same. Where there was a concern about conflating arguments, even arguments which may appear similar, the arguments were kept separate to ensure the internal rigour of the data presented. For example, the ‘slippery slope’ argument, although similar to the argument about whether it is possible to include adequate safeguards, was kept separate. We should also note that this article reports on the arguments made during parliamentary debates as recorded by Hansard. This does not, however, necessarily reflect the politicians’ personal opinions or their actual reasons for voting a particular way. For example, a person may vote against a VAE Bill because they personally believe that it is wrong to ever kill another human being, but may actually say that VAE is wrong because it is difficult to protect the vulnerable. The researchers have no way of knowing or verifying whether, and to what extent, this is in fact the case.

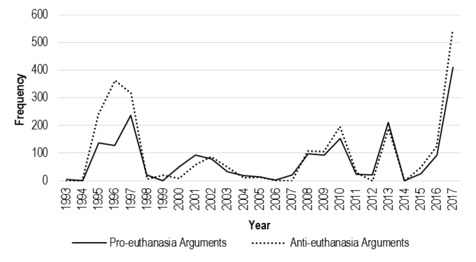

EAS has a turbulent politico-legal history both internationally and within Australia.[12] In total, as at 22 December 2017, 58 Bills have been introduced in Australian jurisdictions seeking to legalise or decriminalise EAS, demonstrating support for progressive end-of-life policies. Figure 1 outlines the frequency with which both pro- and anti-EAS arguments have been advanced throughout Australia from the period 1993–2017 (arguments presented more than once by the same politician not repeated, as noted above). As can be seen, in 1996 the arguments advanced against legalising EAS far outweighed those in support. As of December 2017 however, this position has changed so that the frequency of arguments both in support of and against legalising EAS, as advanced by politicians throughout Australia, are closer aligned, with the Voluntary Assisted Dying Bill 2017 (Vic) being passed in Victoria in late 2017.

Figure 1: Frequency of Pro- and Anti-EAS Arguments Advanced in Parliament (across Australia)

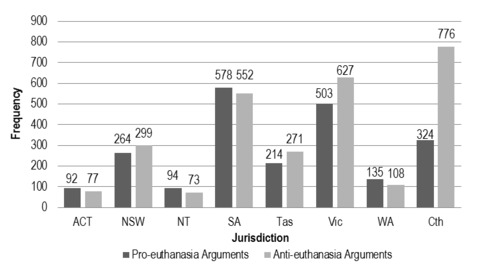

Figure 2 sets out the frequency of the arguments advanced within each Australian jurisdiction. There is a prevalence of anti-EAS arguments in the Commonwealth Parliament. Anti-EAS arguments are also prevalent, albeit to a lesser degree than in the Commonwealth, in Victoria, Tasmania, and New South Wales. In the remaining states and territories, pro-EAS arguments are slightly more prevalent.

Figure 2: Frequency of Pro- and Anti-EAS Arguments Advanced in Parliament (per Jurisdiction)

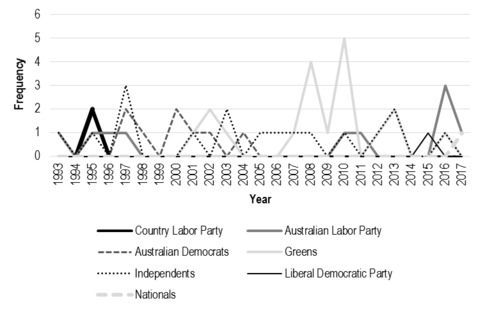

Of the 58 Bills introduced, 89.7 per cent reached the Second Reading, while only 15.5 per cent proceeded to the Committee Stage. Nearly half of the Bills (48.3 per cent) lapsed, 10.4 per cent were discharged or withdrawn and 31 per cent were defeated.[13] The high rate of lapsing or defeat reflects the fact that 81 per cent of Bills were introduced by independent Members of Parliament (29.3 per cent) or minority parties (51.7 per cent), and that the remaining 19 per cent of Bills were introduced by members of the two major parties, either independently or together with a member of a minority party, as Private Members’ Bills (see Figure 3).[14] Only 26 members have been responsible for introducing the 58 Bills seeking to regulate EAS, reflecting the fact that a disproportionate burden for initiating debates lies on individual members.[15]

Figure 3: EAS Bills Introduced per Party/Independents over Time

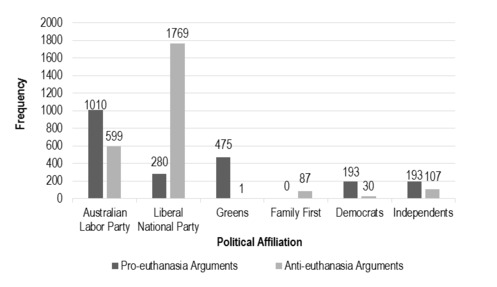

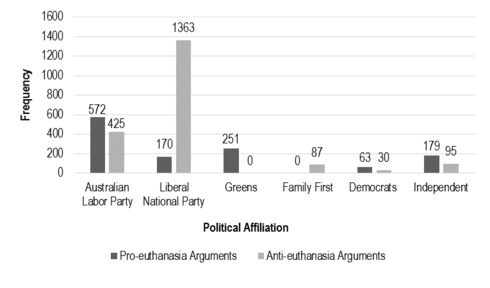

Of particular note, although each division on EAS within Australia has been a conscience vote, the votes of individual members tend to strongly correlate with their party affiliations and coalitions. Some minor parties, such as the Greens and the Democrats, are more likely to support pro-EAS measures (99.7 per cent Greens and 86.5 per cent Democrats). However, conservative minor parties with direct religious affiliations, such as the Family First Party and Christian Democratic Party, have universally opposed the passage of EAS legislation. Whilst the Liberal and Labor parties permit conscience votes, Liberal Party members are more likely to oppose EAS (86.3 per cent), whereas Labor Party members are more likely to be in support (62.8 per cent).[16] Figure 4 sets out the frequency of arguments advanced in accordance with political affiliation. This figure illustrates the frequency of arguments advanced by the major parties, some minor parties, and independent members. Not all parties with members involved in the EAS debate have been included in the table in deference to ease of reading.

Figure 4: Political Affiliation (Main Parties and Independents)

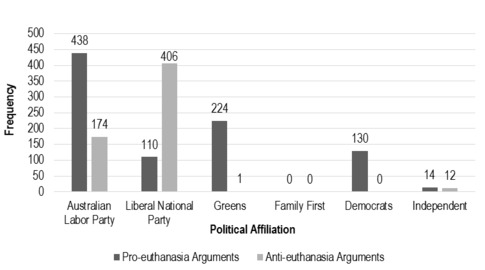

Figures 5 and 6 detail the gender of the politicians advancing the arguments. As can be seen from these tables, male Labor and Liberal Party members put forward significantly higher numbers of anti-EAS arguments. Male Liberal Party members appear to be significantly anti-reform.

Figure 5: Male Politicians’ Arguments (by Party)

Figure 6: Female Politicians’ Arguments (by Party)

This Part has provided an overview of the frequency of the arguments for and against EAS, and who is making them. The next Part will examine the basis and content of those arguments in detail.

V POLITICIANS’ PERCEPTIONS REGARDING VOLUNTARY ACTIVE EUTHANASIA AND PHYSICIAN-ASSISTED SUICIDE

EAS is a controversial subject provoking intense emotional responses, reflecting the fundamental convictions and values of disparate segments of society. Consequently, it has been perceived as an intractable issue, with little scope for the possibility of reaching agreement between various interest groups. However, the existence of equally passionately held positions within a debate does not imply that the arguments are equally persuasive and that there is no basis to decide between them. Within Australia, a significant obstacle to legalising EAS despite overwhelming public support has been a political reluctance to consider reform. This Part will present the arguments that have been advanced by politicians against and in support of EAS with a view to providing an overview of those arguments. This will facilitate assessment of the political landscape which will contribute to the progression of the EAS debate. Annexure A provides a skeletal outline of the politicians’ arguments that will be presented in this Part.

The arguments advanced against EAS may be categorised very broadly into non-consequentialist, consequentialist, or legalistic arguments. We use the term ‘non-consequentialist’ here to include any argument that appeals, not to the consequences of legalising EAS, but to the intrinsic moral status of EAS. To illustrate, a politician might say that it is always wrong to take a person’s life because life is a gift from God, and only God has the right to take away life (we give examples of politicians raising this argument below). This is a non-consequentialist argument. By contrast, arguments that appeal to the consequences of EAS discuss the possible impacts of legalisation on vulnerable patients who may not want EAS. For example, the question, ‘How can we be sure that only those who qualify for EAS under the proposed law will have access to EAS?’ is a consequentialist question in our definition because it is asking about the possible consequences of legalising EAS, namely, that some people who do not qualify for EAS may nonetheless gain access. A proponent of this argument may accept that, in principle, it would be right to allow EAS for the patient who fulfils the required criteria under the proposed statute, but might still claim that EAS should not be legalised because no statute can ever provide sufficient safeguards to protect those who do not qualify from having their lives ended under the legislation. We call arguments that focus on the consequences for others, as this argument does, a ‘consequentialist’ argument. Note, however, that, as we use that term here, ‘consequentialist’ does not coincide with the ethical position known as consequentialism, which has a technical meaning in ethical philosophy.[17] Instead, we use the term here in a non-technical and non-philosophical way to refer only to those arguments that appeal to the consequences of legalising EAS. The term ‘legalistic arguments’ refers to arguments that generally attack the drafting of legislation or the workability of safeguards included in legislation, seeking to argue that it is impossible for drafters to make them sufficiently robust and avoid unforeseen loopholes.

The first class of non-consequentialist arguments is theistic. The theistic arguments are generally premised on the sanctity of life as a gift from God, and the mysteries surrounding the dying process. The second class of non-consequentialist arguments is secular. They are premised on the inalienability of the right to life[18] or a belief that life has absolute value. We shall now deal with each of these, and their subcategories, in turn.

(i) ‘Religious Sanctity of Life’ Argument

The ‘religious sanctity of life’ (‘SOL’) argument holds that the intentional destruction of life is morally wrong in an absolutist sense (raised 35 times; 1.39 per cent of all anti-EAS arguments (‘AEA’)).[19] For example, Brett Whiteley[20] has stated that, whilst in some circumstances a person might feel that another should be killed, ‘it is my understanding that God has a “no-kill policy”’.[21] Consequently, insofar as VAE involves the destruction of a person’s life, it cannot be permitted.[22] Indeed, one proponent of this argument has expressly stated that life possesses an ‘absolute value’.[23] This approach assumes the existence of some absolute moral objective value which may be attributed to a person’s life or, alternatively, a moral prohibition against intentional killing.[24] In response to arguments promoting a right or interest in self-determination, a ‘religious SOL’ claim has been ‘God giveth and God taketh’.[25] A succinct statement of this view is given by Paul Gibson[26] in the following terms: ‘God gave us the greatest gift of all: the gift of life. In my opinion He created us and He is the only person that has the right to take away that life’.[27]

The basis of this claim is that, because life was conferred by God, it does not ‘belong’ to the individual and therefore they are entitled to self-determination only within the prescriptions made by God. The conferral of life by God appears to have two corollaries: (a) that God is the only entity entitled to take life;[28] and (b) life possesses a special sanctity.[29] Other politicians seek to justify the existence of this objective moral imperative on the basis that all other world religions support the prohibition against killing and the SOL.[30] Only one politician adopting the ‘religious SOL’ approach discussed exceptions to the commandment ‘thou shalt not kill’: such exceptions are stated in the Bible, and include self-defence and war, but not the relief of intolerable suffering.[31]

Politicians advance four arguments rebutting this ‘religious SOL’ approach. The first, which is generally raised in response to most religious arguments, is that, in a diverse and pluralistic society, the religious beliefs and attitudes of certain segments of the community should not be imposed by law on others who do not possess the same beliefs and attitudes (raised 109 times; 5.5 per cent of all pro-EAS arguments (‘PEA’)).[32] The second argument is that a compassionate God would not permit the extreme suffering experienced by some terminally ill persons (raised 16 times; 0.8 per cent of PEA).[33] The third argument is that if God possesses the exclusive domain over life and death, then to extend life through artificial means must be equally wrong as ending life prematurely (raised two times; 0.1 per cent of PEA).[34] The fourth argument is that there are existing exceptions to the sanctity of life, such as war (raised 11 times; 0.6 per cent of PEA).[35]

(ii) ‘Suffering Serves a Higher Purpose’ Argument

Another theistic argument advanced is that suffering serves a ‘higher purpose’. Richard Alston,[36] for example, recounted the experience of his father suffering in a nursing home and stated that ‘he would have realised that the suffering that he was going through did have a higher purpose’.[37] Few of the statements advanced by politicians along these lines serve to explain what ‘higher purpose’ suffering might be regarded as advancing. Some of those who do offer more clarity suggest that to terminate a person’s life may prevent them from making their peace with God and cause further suffering.[38] This presumes, of course, that the individual adheres to the Christian faith.

Politicians have responded to this argument with similar arguments to those used in their rebuttal of the ‘religious SOL’ approach, discussed above. However, Bob Such[39] adds the following rebuttal:

The Social Development Committee heard evidence from a senior cleric ... who indicated that pain was good because it had a purpose. My view is that if someone is saying that pain is good, they mean pain for someone else, not for their own situation.[40]

(iii)‘EAS Contravenes Australia’s Judaeo-Christian Social Values’ Argument

Some anti-EAS politicians have rejected EAS on the basis it contravenes Australia’s ‘Judaeo-Christian social values’ (raised 10 times; 0.4 per cent of AEA). This argument proceeds on the assumption that society, and Australia’s democratic system, are underpinned by Judaeo-Christian values, and therefore laws should not be passed which significantly conflict with the central Judaeo-Christian tenets. For example, Gary Humphries[41] has stated: ‘whether or not we profess to have particular religious convictions ... it remains true that Judaeo-Christian values and tenets underpin the basis of our society, including our obligations and rights as citizens to observe the law’.[42] Similarly, Nicholas Sherry[43] has stated: ‘To me, much of the central tenets of Christianity, which have played a very important role in the set of ethics that we as a Western society observe, are particularly important’.[44]

While similar rebuttals to those levelled against the SOL approach have been raised against this argument, other politicians have reflected on the increasing diversity and secularity of Australia (raised 109 times; 5.5 per cent of PEA). For example, Ernest Page[45] has argued:

While I might have one moral view on a matter and Fred Nile might have another moral view, it is not the right of a pluralist society to enact laws to reflect my moral view on that matter. The laws are passed to benefit and safeguard people in this pluralist society, not to impose upon others a moral or ethical view that I might have. We have to treat this matter in that light. I cannot say that merely because I believe something is morally or religiously correct somehow my view should be imposed by law on other people. About 10 years ago people had their legitimate moral objections to amendments to provisions of the Crimes Act which dealt with homosexual law reform.[46]

The view that the law is based on Judaeo-Christian moral values has been rejected by other politicians on the grounds that such a view fails to reflect our culturally diverse society and that it is wrong to impose one set of moral values on others in such a culturally diverse society.[47] Bob Such expressed this point particularly strongly by drawing an analogy between the imposition of religious moral values by the prohibition of EAS (preventing people from having the freedom to choose it for themselves should they wish) and the Taliban’s draconian legal regime.[48]

Some politicians on both sides of this issue have also recognised the fundamentally secular nature of Australia’s democracy.[49] For example, Kim Carr[50] has stated:

[First] the sacredness of life, and the argument that no human being has the right to intentionally take away ‘a gift from God’. Obviously, these are religious concepts, and I respect the right of any Australian to declare or practice [sic] their religion, and to choose life over any other consideration for themselves. However, Australia is a secular nation, and as its Parliament, we have an obligation to make secular laws, not religious ones.[51]

We will present the secular arguments advanced against EAS in this section.

(i) ‘Secular Respect for Life’ Argument

A common secular position advanced in 3.9 per cent of political arguments opposing EAS is the respect for life (‘RFL’) argument (raised 97 times). The RFL argument appeals to the purported inherent value of human life whilst simultaneously avoiding the criticism of ‘religious zealotry’.[52] As with the ‘religious SOL’ argument, the RFL approach is used to reinforce the proposition that killing is fundamentally wrong.

These arguments call upon either the fundamental values of Australia[53] or civilised societies generally[54] to support the proposition that euthanasia is fundamentally wrong. In killing another person, we are, on this argument, necessarily failing to respect life.

The primary response (raised 261 times; 13.2 per cent of PEA) to the RFL approach is the ‘autonomy objection’. This holds that every person is an autonomous being and is therefore entitled to decide the circumstances under which their life ends when they are experiencing intolerable and interminable suffering.[55] A related argument (based on autonomy) is that the state should not interfere with exercises of autonomy within the private sphere of a person.[56] Andrew Whitecross,[57] for example, has argued that autonomy is a value just as sacred as human life is said to be. So, by slavishly pursuing the sanctity of life value, we may end up diminishing other equally sacred values.[58] Even some opponents of EAS have recognised the importance of autonomy by claiming that it coexists with the sanctity of life.[59]

The second response to the RFL approach, which is less common, is the reverse sanctity of life objection. The objection is that EAS in fact respects and advances the sanctity of life by ensuring that persons are not required to suffer a protracted, painful and undignified death (this argument has been invoked both against the religious version[60] and the secular one).[61] Another, third, argument (raised 11 times; 0.6 per cent of PEA) is the limited value objection. This is that the sanctity of life value is not an ‘absolute value’.[62] Sam Bass,[63] for example, argued that the sanctity of life must, at some point, give way to the respect for quality of life.[64]

A fourth response to the RFL approach is the selective deployment argument (raised 14 times; 0.7 per cent of PEA). This stresses the exceptions to the sanctity of life, criticising proponents of the SOL[65] and RFL[66] arguments for selectively deploying them. For instance, Alison Xamon[67] claimed that there is a certain hypocrisy to permitting young soldiers to die at war, but simultaneously refusing the elderly the right to die with dignity.[68] Those who refuse the latter, without recognising its inconsistency with the former, are selectively deploying SOL or RFL. The fifth objection is the pluralistic morality objection (raised 109 times; 5.5 per cent of PEA), which applies equally to the SOL argument and the RFL approach and also overlaps with the rebuttal of the Judaeo-Christian social values argument discussed above. The objection is that the moral values, beliefs and attitudes of one set of persons should not be imposed on others.[69] The sixth objection is the humane consequentialist objection (raised 55 times; 2.8 per cent of PEA), which points out that the effect of rigorously adhering to the sanctity of life argument is to cause people to suffer degrading, undignified and painful deaths, frequently through starvation, due to the refusal of nutrition and hydration.[70]

(ii) ‘Suffering Is Ennobling’ Argument

Another argument, which is similar to the theistic ‘higher purpose’ argument, is the secular position that suffering is ennobling (raised seven times; 0.3 per cent of AEA) and that the dying process can be a beneficial experience for self-discovery and family healing (raised 21 times; 0.8 per cent of AEA). For example, Patricia Worth[71] has argued that the end of a person’s life can be a time of enormous growth and understanding which should not be prematurely curtailed by permitting VAE.[72] The argument that pain can be ennobling has been criticised on the basis that there is nothing noble, beautiful, or redeeming about pain and suffering and,[73] further, that the persons advancing this argument are rarely the ones in pain.[74]

(iii) ‘Social Cornerstone’ Argument

The ‘social cornerstone’ argument has been regularly invoked by Australian politicians against permitting EAS (raised 92 times; 3.7 per cent of AEA).[75] This derives from a House of Lords Select Committee Report which stated that the prohibition on intentional killing is ‘the cornerstone of law and of social relationships’.[76] It has been said that Australia possesses a culture of ‘life’, and that transitioning towards EAS would convert Australia’s culture into one of ‘death’.[77] This would occur through the ‘normalisation’ of death.[78] This position is similar to the SOL, Judaeo-Christian values and RFL arguments insofar as it assumes the existence of a uniform Australian value set. The ‘social cornerstone’ argument has been countered with the pluralistic morality objection discussed above (raised 109 times, 5.5 per cent of PEA). Opponents of the argument have also objected that jurisdictions which have legalised EAS, such as Oregon or the Netherlands, have not transitioned towards a culture of death.[79]

(iv) ‘Indigenous Interests’ Argument

An argument less commonly advanced against EAS is the ‘Indigenous interests’ argument (raised 20 times; 0.8 per cent of AEA). There are two aspects to this argument. The first is that EAS is fundamentally incompatible with Indigenous values because if EAS becomes a common feature of medical facilities it may result in a worsening in Indigenous health outcomes due to either: (a) fear that they will be killed;[80] or (b) the inconsistency between the practice of EAS and fundamental cultural values.[81] The second aspect of the argument is that Indigenous persons are especially susceptible to influence by community groups and relatives and therefore are more likely to accept VAE under duress.[82]

The Indigenous values argument can be challenged by the pluralistic morality objection discussed above. Politicians have argued that cultural value differences within the Indigenous population cannot dictate public policy.[83] Sandra Kanck[84] has objected to the argument on the basis that when the Rights of the Terminally Ill Act 1995 (NT) (‘ROTTIA’) was in force in the Northern Territory,[85] there was no evidence of a decline in Indigenous attendance at medical facilities.[86] Peter Andren[87] has argued that Indigenous customary law, which is arguably inconsistent with EAS, is not an appropriate foundation to refuse to permit EAS.[88] Politicians have also reflected on the fact that Indigenous persons’ fears that they will be involuntarily euthanised are directly inconsistent with the fact that the Bills have only permitted voluntary euthanasia.[89]

(v) ‘Equality’ Argument

The ‘equality’ argument is relatively uncommon (raised 21 times; 0.8 per cent of AEA). It holds that the prohibition against intentional killing reflects the principle of equality and equal justice insofar as it protects all persons equally.[90] Opponents of EAS have buttressed this contention by reference to John Stuart Mill’s principle that no person could, in the name of freedom, sell themselves into slavery, and this is also why the law rejects consent to grievous bodily harm as a defence to that offence.[91] The rationale is that although a person may make a rational decision to sell themselves into slavery, even if morally offensive, it may result in other vulnerable persons being sold into slavery without making the same rational decision.[92] The same logic applies to EAS. Sandra Kanck, however, has responded that the analogy with the prohibition against slavery is a sophistic rhetorical device used simply to score points in an argument, with no relationship with reality.[93] Others have argued that legalising EAS in fact promotes inequality because currently persons who are well-connected and resourced may access EAS, while those who are socio-economically disadvantaged may not.[94] Similarly, the current laws permitting suicide but not assisted suicide may operate to indirectly discriminate against persons who are unable to bring about their own death.[95]

(vi) ‘Privacy’ Argument

The ‘privacy’ argument (raised nine times; 0.4 per cent of AEA) holds that the deathbed of a person is an extremely private and sensitive place which should be entirely free from legislative intervention. EAS would involve the intrusion of the state into this private space by imposing cumbersome rules and procedures.[96] A related contention is that the law is a ‘blunt instrument’ maladapted to the subtle nuances of end-of-life decisions.[97] However, Alison Xamon has argued that the prohibition against EAS is intruding on the privacy of a person’s deathbed, and that, by providing the option of EAS, the state would remove an incursion on the privacy of the dying process.[98] As well, without an appropriate legislative framework, compassionate medical practitioners and families are currently exposed to the risk of prosecution for advancing the wishes of the patient.[99] This is also an unacceptable intrusion of privacy and so the ‘privacy’ argument, for Alison Xamon, actually undermines the arguments against EAS.

(vii)‘Message’ Argument

This argument involves the claim that the legalisation of EAS will send the ‘wrong message’ to the community, in particular to vulnerable segments of the community which have a higher propensity for suicide (raised 71 times; 2.8 per cent of AEA).[100] The ‘message’ is that suicide is a valid solution to their problems,[101] some lives are not worth living,[102] or that some lives are not worth protecting.[103] Some politicians have countered that existing high rates of suicide have not been caused by the presence of EAS, and that the legalisation of EAS cannot be logically connected, except in the most tenuous way, to high rates of suicide (raised seven times; 0.4 per cent of PEA).[104] It has been noted that any supposed ‘message’ is limited to a very specific group of persons in confined circumstances, and does not equate to people dying ‘at whim’.[105] Finally, Robin Chapple[106] has argued that EAS ‘is about choice. It is not about encouraging suicide or passing moral judgment’.[107]

(viii)‘Medical Compulsion’ Argument

The ‘medical compulsion’ argument expresses the concern that, if legalised, physicians may be compelled to administer EAS contrary to their beliefs and values (raised 10 times; 0.4 per cent of AEA).[108] This argument may be limited because all EAS Bills have expressly permitted conscientious objection or refusal to participate in administering or providing a lethal dose.[109] However, Dennis Hood[110] has noted that some medical practitioners may seek to refuse even to advise the patient that another physician may be willing to provide EAS[111] (as is required under some, but not all, EAS Bills).

(ix)‘Discrimination’ Argument

The ‘discrimination’ argument embodies the claim that EAS may result in discriminatory perceptions and treatment of the elderly, ill and disabled (raised 34 times; 1.4 per cent of AEA).[112] For example, two politicians have noted that a physician might advise a young person requesting EAS to attend counselling, whereas they are more likely to accede to the request of an elderly person.[113] It has also been suggested that VAE discriminates against the poor who may not have the resources to receive high quality palliative care.[114] Others have contended that any legislation which limits the category of people who may access VAE may be discriminatory or create arbitrary lines by precluding access to children, the mentally incompetent, or even those who are not terminally ill.[115] The argument is that, since it cannot be legalised in a non-discriminatory way, it should not be legalised at all. This contention is frequently connected with the consequentialist argument of ‘scope creep’.[116] The most common reply to the ‘discrimination’ argument (raised twice; 0.1 per cent of PEA) is to contend that the current framework is itself discriminatory, because able-bodied persons are able to terminate their own life legally through suicide,[117] and persons who are well-connected and resourced may access VAE.[118]

(x) ‘Maturity’ Argument

This argument holds that society is insufficiently ‘mature’ to legalise EAS, which is evidenced by the poor administration of public healthcare funds.[119] This argument was advanced only by Jon Ford,[120] and appears to be connected with a fear that EAS may be used as a tool of economic rationalism, which is discussed under the ‘slippery slope’ argument below.[121] No politician directly rebutted this argument and it is unclear what precise form the ‘maturity’ argument takes.

(i) ‘Slippery Slope’ Argument

The ‘slippery slope’ argument states that in the event that EAS is legalised, it will cause long-term adverse consequences which substantially outweigh the benefits derived from EAS (raised 160 times; 6.4 per cent of AEA). The two main versions of the ‘slippery slope’ argument are the universalised rule version and the ‘scope creep’ version. The ‘universalised’ rule version holds that even though a particular case of EAS may be ethically permissible on its facts, it would result in socially unacceptable consequences if we legalised EAS on the basis of the particular case. We cannot be sure that every case would be of exactly the same kind, so a universal rule is too blunt an instrument. The argument is that, since a universalised rule would cause these socially unacceptable consequences, the individual act must itself be unethical or prohibited.[122] The distinction between the universalised rule and the ‘scope creep’ version is that the latter depends on the rational extension of the categories of persons to whom EAS may become available; there are no morally relevant differences to justify allowing some categories of people to have access while ruling out access for other categories.

The soundness of the universalised rule version of the ‘slippery slope’ argument relies on empirical assumptions about the consequences of legalising EAS, including:

1. Risks to the elderly, vulnerable, socially marginalised and frail (raised 39 times; 1.6 per cent of AEA).[123]

2. Risks of avaricious relatives or unscrupulous medical practitioners abusing EAS (raised 42 times; 1.7 per cent of AEA).[124]

3. Risks of misdiagnoses or inaccurate prognoses (raised 61 times; 2.4 per cent of AEA).[125]

The scope creep version of the ‘slippery slope’ argument claims that the distinctions between the categories of persons to whom EAS is available are arbitrary and that the rational extension of these categories to others is inevitable, thereby producing socially unacceptable outcomes.[126] For example, should VAE be extended to children or persons who are mentally incompetent who experience a terminal illness causing unbearable pain?[127] The argument is based on the difficulty of drawing a clear line separating those entitled to have access to VAE from those who should be excluded.[128]

A variation of the ‘slippery slope’ argument is the dilution of safeguards concern. This is the claim that the strict safeguards contained within the legislation may be diluted by future parliaments.[129]

The ‘universalised rule’ version has been rebutted on the basis that the perceived adverse consequences of universalising the rule are merely illusory, with reference to empirical support from the Netherlands and Oregon experience (raised 39 times; two per cent of PEA).[130] Others argue that the ‘slippery slope’ argument ignores the presence of procedural safeguards within the legislation designed to preserve the voluntariness of euthanasia (raised 71 times; 3.6 per cent of PEA).[131] Ian Cohen has noted that the fear of the slippery slope is exacerbated where VAE is unregulated.[132] Furthermore, VAE legislation merely operates to decriminalise and regulate an existing practice, rather than actually create a new permissive regime.[133] Some politicians have noted that EAS will prevent the kinds of undesirable behaviours targeted by the ‘slippery slope’ argument, because it safeguards and promotes awareness of patients’ rights (raised 80 times; 4.1 per cent of PEA).[134] In relation to the scope creep argument, a common rebuttal is that society is perfectly capable of making meaningful moral distinctions between categories of individuals and classes of acts (raised 18 times; 0.9 per cent of PEA).[135]

(ii) ‘Duty to Die’/‘Perverse Altruism’ Arguments

The ‘duty to die’ and ‘perverse altruism’ arguments are distinct, but related, positions which state that the social pressures created by the legalisation of EAS would result in situations where people who do not want EAS end up choosing it. The ‘duty to die’ argument (raised 89 times; 3.5 per cent of AEA) suggests that legalising EAS will generate subtle and overt pressures on vulnerable persons, converting their right to die into a moral duty or obligation to die.[136] Politicians advancing this argument say that this may occur where the vulnerable person perceives that they are a burden on their family or society generally.[137] The ‘perverse altruism’ argument (raised 59 times; 2.3 per cent of AEA) appeals to the same circumstances, but argues not that the individual will feel coerced or pressured into receiving EAS, but rather that they may decide to receive EAS because they perceive it to be the most appropriate outcome for their family.[138] The difference is that, in the ‘duty to die’ version, the vulnerable person may still make the decision to die but not want that outcome. By contrast, in the ‘perverse altruism’ version, it becomes part of the vulnerable person’s own moral framework that she or he ought not to be a burden, and so the decision to die remains, in essence, their decision. We may not, however, want our society to embrace such a moral position, or want it to become so prevalent a position taken by vulnerable people in our society. A common reply (raised 71 times; 3.6 per cent of PEA) to the ‘duty to die’ and ‘perverse altruism’ arguments is that appropriate regulation and procedural safeguards may protect against a patient choosing EAS in circumstances where they are motivated by subtle community pressures or familial circumstances.[139] As well, it has been argued that because the threshold and procedural requirements of EAS encourage open discussion, this enables medical practitioners to address any patient concerns, including the perception that they are a burden (raised 57 times; 2.9 per cent of PEA).[140]

(iii) ‘Social Risk’ Argument

The ‘social risk’ argument holds that EAS, although ethically permissible, should not be legalised because this may result in exposing the marginalised, frail and elderly to unacceptable social hazards (raised 192 times; 7.6 per cent of AEA).[141] These social hazards derive from concerns about subtle social pressures to undergo EAS[142] (and so overlap with the ‘duty to die’ and ‘perverse altruism’ arguments), and from concerns that the legislation may be manipulated or abused so as to result in the illegitimate killing of vulnerable persons.[143] A rebuttal to this (raised 39 times; two per cent of PEA) is that the social risks are not evident from the Netherlands and Oregon experience.[144] A further response (raised 71 times; 3.6 per cent of PEA) is that appropriate procedural safeguards can address the relevant social risks.[145]

(iv) ‘Hippocratic Oath’ Argument

The ‘Hippocratic Oath’ argument is based on the premise that intentional killing is fundamentally inconsistent with medical ethics.[146] However, its force actually lies in concerns about the consequences of violating the medical ethic of first doing no harm.

Supporters of the ‘Hippocratic Oath’ argument claim that permitting EAS:

1. destabilises the structure underpinning the medical profession and the Hippocratic Oath (raised 73 times; 2.9 per cent of AEA);[147]

2. erodes the trust underpinning the doctor–patient relationship (raised 39 times; 1.6 per cent of AEA);[148] and

3. alters the historic role of doctors (raised 29 times; 1.2 per cent of AEA).[149]

The argument is also partly based on a concern that EAS may be used as a tool of rationing, normalising death as a cost-effective solution to the patient’s ailments (raised 44 times; 1.7 per cent of AEA).[150]

Replies to the ‘Hippocratic Oath’ argument include:

1. The emergence of contemporary medical technologies has resulted in the ability to sustain life longer than desirable. Responsible medical treatment must involve consideration of euthanasia (raised 14 times; 0.7 per cent of PEA) in appropriate circumstances.[151] However, this reply is open to the counter-objection that patients currently have the right to request the withdrawal of treatment (raised 56 times; 2.2 per cent of AEA), and so do not need euthanasia on this ground.[152]

2. Euthanasia is already being administered by medical practitioners in a clandestine and secretive environment and it should be regulated (raised 105 times; 5.3 per cent of PEA).[153]

3. A significant part of the Hippocratic Oath includes caring for patients and relieving their suffering, and EAS is consistent with these practices (raised two times; 0.1 per cent of PEA).[154]

4. Focusing on the Hippocratic Oath may be inconsistent with the contemporary movement towards a patient-centric medical paradigm (raised once; 0.1 per cent of PEA).[155]

(v) ‘Existing Practices Are Sufficient’ Argument

This argument is commonly made by opponents of EAS (7.8 per cent of AEA). There are two limbs to the argument: (a) palliative care is the appropriate means of managing intolerable pain (raised 141 times; 5.6 per cent of AEA); and (b) the patient already has the right to seek the withdrawal of medical treatment and artificial nutrition and hydration (‘ANH’), and may receive potentially lethal dosages of analgesics under the doctrine of double effect (raised 56 times; 2.2 per cent of AEA). A compassionate society may satisfy its obligations to suffering patients through palliative care and so it is unnecessary to legalise EAS.[156] A central assumption in this argument is that only a very small percentage of persons are unable to get adequate pain relief with appropriate palliative care programs.[157] Public policy cannot be justified by reference to such a small fraction of persons within the community.[158] It has also been argued (raised five times; 0.2 per cent of AEA) that as medical technology becomes increasingly advanced, and palliative care becomes more sophisticated, EAS will become progressively less relevant.[159] Finally, some politicians have argued that any deficiencies in palliative care services should be remedied through improving palliative care facilities rather than by making EAS available.[160]

The main objections to the palliative care limb of the argument are:

1. Palliative care has limitations (raised 135 times; 6.8 per cent of PEA). It may mitigate most physical pain, but it may be inadequate to mitigate existential, emotional and psychological suffering.[161] Also, palliative care is ineffective for a small number of patients, and may not even be available to persons who are socio-economically disadvantaged or geographically remote.[162]

2. Palliative care and EAS are not mutually exclusive and are simply two ends of a continuum. Both must be available to promote effective patient decision-making (raised 59 times; 3 per cent of PEA).[163]

The second limb of the argument appeals to existing medical procedures which may already lawfully be used to bring about the death of the patient. Some have argued that the right to refuse treatment (including ANH) is sufficient to enable the termination of a person’s life (raised 56 times; 2.2 per cent of AEA).[164] Some have also noted that suicide is permitted in Australia (raised twice; 0.1 per cent of AEA).[165] As well, some note that appropriate palliative care may involve hastening death by administering high dosages of analgesics, which can achieve substantially the same result as VAE.[166] However, they distinguish this component of palliative care from VAE on the basis of the intention–foresight distinction under the doctrine of double effect (raised 60 times; 2.4 per cent of AEA).[167] Some politicians have, however, noted that the distinction between proper palliative care under the doctrine of double effect and VAE is ‘a very fine one indeed’.[168]

The primary replies to this limb of the argument are:

1. There is legal hypocrisy in permitting the withdrawal of ANH and medical treatment, which may cause a prolonged and inhumane death, while prohibiting the same outcome by the administration of euthanasia for a quick and painless death (raised 49 times; 2.5 per cent of PEA).[169] The counter-objection advanced by opponents (raised 18 times; 0.7 per cent of AEA) is that it does not involve causing death,[170] or the intention to bring about death.[171]

2. The appeal to the doctrine of double effect embodies another example of legal hypocrisy because a medical practitioner intending to relieve pain by causing death would commit murder, whereas a medical practitioner intending to relieve pain while merely foreseeing that death is a likely result would be engaging in proper medical practice (raised 14 times; 0.7 per cent of PEA).[172]

3. The doctrine of double effect is a doctor-centric approach which permits medical practitioners to effectively control the circumstances and time of the patient’s death without their consent; it results in a clandestine and secretive system exposing patients to the risk of involuntary euthanasia (raised 35 times; 1.8 per cent of PEA).[173]

4. The doctrine of double effect exposes compassionate medical practitioners to the risk of prosecution (raised 50 times; 2.5 per cent of PEA).

(vi) ‘Marginalisation of Palliative Care’ Argument

The ‘marginalisation of palliative care’ argument (raised 30 times; 1.2 per cent of AEA) holds that legalising EAS may have a negative impact on the quality of palliative care units, with resources being diverted to EAS as a more economical way of managing terminally ill patients.[174] The primary reply to this concern is that society will see EAS as a last resort, and therefore increase funding for curative therapies and improved palliative care to prevent patients from seeking EAS.[175] Another reply is that EAS complements palliative care, and therefore funding will be provided to both programs.[176]

(vii)‘Loss of Association’ Argument

The ‘loss of association’ argument holds that EAS may be regretted because it deprives the individual and family members of time and the end-of-life experiences which may be associated with the dying process (raised 21 times; 0.8 per cent of AEA).[177] For example, Paul Gibson stated that no one has the right to make the decision to prematurely terminate their life on behalf of their family, who may consider it rewarding to nurse them through sickness.[178] Sandra Kanck has responded to this argument, countering that it is:[179]

perfectly possible to be complete in your family relationships without having an incurable illness. It is extremely high handed for those with the power to force people to stay alive because they think it is good for people to go through the Kubler-Ross stages of dying, to do so because they think it is life enhancing.

(viii)‘Limitations of Medicine’ Argument

This argument involves the claim that there are significant limitations to contemporary medicine and these justify the retention of the prohibition against intentional killing (raised 61 times; 2.4 per cent of AEA). Examples of the prospect of a ‘miracle’, unexpected recovery,[180] misdiagnosis[181] or inaccurate prognosis are given to support the argument.[182] Allowing EAS in these circumstances may end someone’s life in circumstances where, if treatment were sustained, they may recover fully or partially to have a reasonably long and comfortable life.[183] The main counterargument (raised 71 times; 3.6 per cent of PEA) is that the legislation involves safeguards and independent reviews which significantly reduce the risks involved, including misdiagnosis.[184]

Legal arguments against EAS also exist, which generally attack the drafting of the legislation and the workability of the safeguards, and invoke international law. These will be discussed in this section.

As noted above, one reason the EAS debate stalls is that there is no consistent use of clearly defined terms. Arguments generally relate to the definitions of ‘terminal illness’ and ‘suffering’. They account for 2.6 per cent of politicians’ arguments advanced against EAS (raised 65 times). In particular, if the term ‘terminal illness’ is used, this term normally (on its natural and ordinary meaning) applies only to those who are in the dying phase of their illness.[185] But if this term is defined in the Bill to include incurable illnesses or a disease which, if left untreated, will cause death, then this might mean that the scope of EAS legislation significantly exceeds that implied by the natural and ordinary meaning of the word ‘terminal’. There have been suggestions that loose definitions will permit persons with chronic depression, arthritis or the early stages of multiple sclerosis to receive EAS.[186] One opponent suggested that it might include diabetics who, without insulin, may die.[187] However, Kim Carr has rebutted this argument on the basis that a medical practitioner is likely to refuse EAS in these circumstances, particularly where there are multiple independent opinions.[188]

The ‘right to life’ argument, grounded in international law, provides that Australia is bound to uphold the provisions in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights[189] and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights[190] which provide for the inalienability and inviolability of life (raised 17 times; 0.7 per cent of AEA).[191] This argument has not been directly rebutted.

We will now turn to the pro-euthanasia arguments. The arguments supporting EAS also include non-consequentialist, consequentialist or legalistic arguments. The dominant arguments are almost exclusively secular (raised 1960 times, 99.2 per cent of PEA). Generally, any reference to personal beliefs or conceptions of God are designed to refute arguments or support the ‘pluralistic’ argument, discussed below. This section is shorter than that which considered the arguments against EAS. This is partly because some of the issues raised below have already been discussed in examining the arguments against EAS and the rebuttal of those arguments, so we address them more briefly to avoid repetition. The other reason is that, numerically, there were fewer arguments raised supporting EAS and so there was not the same breadth of views expressed.

There is only one theistic claim in support of EAS. This is that a compassionate God would not expect people to suffer unnecessarily and so would permit people to end their lives (raised 16 times, 0.8 per cent of PEA).[192]

We discussed the ‘autonomy’ argument briefly above when we presented the case against EAS. Here we are examining the argument as it is used in support of it.

The ‘autonomy’ argument is in fact the most common argument advanced in support of EAS (raised 261 times; 13.2 per cent of PEA). The argument is that, within a pluralistic secular democracy, each person has a fundamental right to autonomy and self-determination.[193] Encroachments on a person’s right to autonomy are generally only justified where there is a significant and ethically relevant impact on others.[194] Having regard to the gravity of the dying process, which is intensely personal and private, there ought to be some provision enabling access to EAS.[195] A reply given by some politicians to the ‘autonomy’ argument is that autonomy is fundamentally limited.[196] I do not have the ‘autonomy’ not to wear a seatbelt. The following replies are also typically advanced in relation to the ‘autonomy’ argument:

1. ‘No man is an island’ and it is impossible to separate the interests of the individual from the interests of society (raised 34 times; 1.4 per cent of AEA).[197]

2. The ‘slippery slope’ argument (raised 160 times; 6.4 per cent of AEA).[198]

3. The RFL and SOL arguments (raised 132 times; 5.3 per cent of AEA).[199]

4. Autonomy is subject to limitations within society, and the constraints ought to encompass prohibitions against intentional killing (raised 34 times; 1.4 per cent of AEA).[200]

5. Other objections such as a person ought not to be entitled to receive EAS because of the risk of poor prognostication or misdiagnosis,[201] the individual having been subject to undue influence or duress,[202] the individual seeking to ‘disencumber’ society (that is, stop being a burden to society),[203] the individual may lose valuable personal growth opportunities during the dying process[204] or that it prematurely terminates the dying process which may provide ennobling benefits to the individual.[205]

The ‘pluralistic’ argument (raised 109 times; 5.5 per cent of PEA) holds that, within a multicultural and diverse secular democracy, there are diverse ideological frameworks to which individuals subscribe which may differ in respect of the moral permissibility of EAS. Consequently, the prohibition against EAS operates to impose particular religious or social beliefs on persons who may not subscribe to a similar value system.[206] Proponents of the ‘pluralistic’ argument claim that legalising EAS gives people optimal autonomy, enabling them to exercise their own conscience and beliefs, and does not impose EAS on those persons whose belief system precludes its practice.[207] For example, Margaret Hickey[208] has argued ‘the essence of the legislation lies in its voluntary nature, it offers choice to those seeking to access it. Those who find it repugnant or against their beliefs have but to ignore it’.[209]

The primary replies to this argument are:

1. In relation to EAS, it is impossible to separate the interests of the individual from the interests of society (raised 34 times; 1.4 per cent of AEA).[210]

2. EAS will generate a ‘slippery slope’ (raised 160 times; 6.4 per cent of AEA) and the right to die may become an obligation to die (raised 89 times; 3.5 per cent of AEA), which indirectly imposes the belief system on those persons opposed to EAS.[211]

3. EAS will generate substantial social risks which may result in the involuntary reception of EAS (raised 192 times; 7.6 per cent of AEA).[212]

4. The secular value system of Australian society supports the sanctity of life, and therefore EAS is contrary to the social values underpinning the community, not individuals.[213]

5. EAS is fundamentally inconsistent with the Judaeo-Christian values underpinning Australia’s Western democracy (raised 10 times; 0.4 per cent of AEA).[214]

The ‘right to die’ (‘RTD’) argument is a more specific version of the ‘autonomy’ argument (raised 58 times; 2.9 per cent of PEA). It claims that people within society should have a right to determine the time, means and circumstances of their death.[215]

The primary replies to this argument are:

1. There is already an obligation for others to allow the individual to die if they are competent and other legal requirements are met. This right prohibits interventions to prevent such people from exercising their right to refuse treatment, for example, although it would not necessarily mandate active intervention to deliberately cause death. The RTD, by contrast, would require the latter, but this is killing rather than letting someone die. What EAS really requires is a right to be killed, which imposes a correlative duty to kill (raised 10 times; 0.4 per cent of AEA).[216]

2. The RTD does not exist (raised 4 times; 0.2 per cent of AEA). That is, there is no RTD, in the sense contemplated by PEA activists, in the Australian legal framework.[217]

3. The SOL (raised 35 times; 1.39 per cent of AEA) and RFL (raised 97 times; 3.9 per cent of AEA) arguments which propose that life is ‘sacred’ and inviolable.[218]

(iv) ‘Compassionate EAS’ Argument

This argument maintains that EAS is a compassionate and humane response to the suffering experienced by terminally ill persons (raised 119 times; six per cent of PEA).[219] This is reinforced by the analogy that if a person permitted a pet to continue living in the state that many terminally ill patients suffer, they would be socially condemned or even prosecuted (raised 22 times; 1.1 per cent of PEA).[220] The primary reply to this argument is that EAS is not a compassionate response to another’s suffering (raised 19 times; 0.8 per cent of AEA). A truly compassionate society would increase investment in advanced palliative care and curative therapies, rather than engage in killing the person.[221]

This argument holds that a patient’s right to request the withdrawal of treatment or ANH, or to refuse treatment, is inhumane because it causes the patient to suffer a prolonged and painful death, where the same result may be achieved without the suffering through the active administration of lethal agents (raised 55 times; 2.8 per cent of PEA).[222] On the few occasions that this argument has been rebutted, it is on the grounds that:

1. killing is not a compassionate, effective or dignified response to suffering (raised 19 times; 0.8 per cent of AEA);[223]

2. administering lethal substances does not necessarily cause an instant or painless death (raised 10 times; 0.4 per cent AEA);[224]

3. analgesics may be administered to mitigate the suffering produced through the withdrawal of treatment;[225] or

4. the doctrine of double effect enables the unintentional termination of a person’s life through high dosages of analgesics[226] or the possibility of terminal sedation.[227]

The ‘legal hypocrisy’ argument is that the current law giving the right to refuse treatment, the legal doctrine of double effect and the power for medical practitioners to administer terminal sedation is founded on hypocrisy (raised 49 times; 2.5 per cent of PEA). The argument is advanced on the following bases.

a. Right to Refuse Treatment

It is hypocritical to give patients the right to terminate their life in a prolonged and agonising manner, and yet deny them the right to terminate their life through the active administration of a lethal substance in a more efficient, dignified and comfortable manner.[228]

b. Terminal Sedation

The law enables medical practitioners to induce a state of ‘pharmacological oblivion’ whereby the patient is rendered comatose through the administration of opioids or analgesics.[229] Treatment and ANH are thereby withdrawn, permitting the patient to die in an unconscious state. If terminal sedation is permitted, then it is hypocritical not to permit a patient to request VAE which is not relevantly different from it.[230]

c. Doctrine of Double Effect

The doctrine of double effect permits a medical practitioner to administer progressively higher dosages of analgesics intending to relieve pain where the medical practitioner foresees that a secondary effect may be the hastening of the patient’s death.[231] Some pro-VAE politicians regard the doctrine of double effect as hypocritical because if medical practitioners A and B both administer the same dosage of analgesic which causes death, A will be seen as being an effective palliative care practitioner where A foresees, but does not intend, death, while B may be prosecuted for murder if B intends death as the means of relieving the patient’s pain.[232] This is seen as a doctor-centric approach because the patient is not always involved in the decision to administer the sedatives (even though this may cause their death sooner than might otherwise be the case).[233] If one rejects the moral relevance of the distinction between intention and foresight, this practice is regarded as no different from involuntary or non-voluntary euthanasia.[234] It has also been stated that even if there is a valid distinction between intention and foresight, it lends itself to a secretive and clandestine practice of euthanasia which does not permit honest and transparent doctor–patient dialogue, and which may thus undermine the relationship of trust between medical practitioners and patients.[235]

The various aspects of the ‘legal hypocrisy’ argument are generally criticised on the following grounds:

1. Terminal sedation and the withdrawal of treatment may be distinguished from VAE on the basis that the former practices do not cause the death of the patient (raised 18 times; 0.7 per cent of AEA).[236]

2. Terminal sedation, the withdrawal of treatment and the administration of lethal dosages under the doctrine of double effect are distinguishable from VAE on the basis that, in the context of the former practices, the medical practitioner does not intend to cause death (raised 60 times; 2.4 per cent of AEA), a distinction which retains moral importance as reflected by the law.[237]

(vii)‘Public Support’ Argument

The ‘public support’ argument relies on polling results indicating that nearly 80 per cent of Australians support EAS.[238] The argument is that a democratically elected Parliament should act with due consideration of the constituency (raised 145 times; 7.3 per cent of PEA).

The primary replies to this argument are:

1. Polling results are frequently skewed according to the content and form of the question[239] or are affected by the fact that many Australians do not adequately understand the concept of ‘euthanasia’ or its potential social implications (raised 58 times; 2.3 per cent of AEA).[240] This is contentious because it assumes that members of the community are unaware of the meaning of ‘euthanasia’.[241]

2. Polling results do not typically translate to support in formal referenda or voting processes.[242]

3. The Parliament should impose value judgements which consider the long-term best interests of society (despite what the public itself might think on the issue) (raised six times; 0.2 per cent of AEA).[243]

4. Parliamentary decision-making should not be driven by popularity (raised 26 times; one per cent of AEA).[244]

5. The majority of the public or a member’s constituents oppose EAS (raised 10 times; 0.4 per cent of AEA).[245]

(viii)‘International Comity’ Argument

The ‘international comity’ argument states that EAS is becoming increasingly codified in foreign jurisdictions (raised 6 times; 0.3 per cent of PEA) and that the practice is becoming more accepted internationally (raised 12 times; 0.5 per cent of PEA).[246] This argument is often rebutted on the basis that in such countries statistical evidence indicates that they are sliding down the ‘slippery slope’.[247]

The claim in this argument is that implementing EAS will protect patients (raised 80 times; 4.1 per cent of PEA) and physicians (raised 50 times; 2.5 per cent of PEA). It is argued that patients will be protected because providing a legal facility for EAS will make existing euthanasia practices transparent and provide extensive safeguards for EAS.[248] This will also reduce the risk of physician-initiated euthanasia, duress and undue influence.[249] Additionally, compassionate medical practitioners who accede to the requests of patients to terminate their life will be protected from criminal prosecution.[250] By providing a regulatory framework within which euthanasia operates, increased scrutiny, transparency and accountability for existing practices (raised 57 times; 2.9 per cent of PEA) can be ensured.[251]

The primary replies to this argument are that legalising EAS may:

1. lead to the slippery slope (raised 160 times; 6.4 per cent of AEA);[252]

2. convert the right to die into a moral duty to die due to subtle and overt social pressures (raised 89 times; 3.5 per cent of AEA);[253] or

3. produce a range of social risks exposing vulnerable persons to the risk of involuntary euthanasia (raised 192 times; 7.6 per cent of AEA).[254]

This argument claims that compassionate medical practitioners are currently subject to pressure by patients to terminate their lives when they are suffering unbearable and persistent pain, yet the medical practitioners are unable to accede to the request due to the legal prohibition on VAE.[255] This argument is infrequently relied on (raised 12 times; 0.6 per cent of PEA). There have been no direct objections raised by politicians.

The ‘prevalence’ argument holds that euthanasia is already frequently practised in Australia and should be regulated by establishing a legal framework permitting VAE (raised 105 times; 5.3 per cent of PEA).[256] It partly overlaps with the regulatory argument just presented above. The primary replies to this argument are (1) that it is like saying that, since some people will obtain high powered automatic guns whether we regulate or not, we might as well allow them to do so, and regulate the guns rather than ban them. But a prohibition clearly still will protect people from abuse and save lives (0.1 per cent of AEA);[257] and (2) if medical practitioners are currently willing to breach a blanket prohibition against euthanasia, they will equally be willing to breach the safeguards contained within VAE legislation (raised 43 times; 1.7 per cent of AEA).[258]

This argument proposes that the prohibition against EAS provides an example of the state administering theologically based laws, which violates the separation of church and state (raised nine times; 0.5 per cent of PEA).[259] An objection to this argument is that many opponents of EAS are not motivated by religion.[260] Lindsay Tanner[261] has also rejected this argument on the basis that whether a church takes a particular position on a matter is irrelevant when determining whether it should be prohibited or permitted by law.[262]

The passing of the Voluntary Assisted Dying Act 2017 (Vic) is likely to lead to renewed efforts to change the law in other Australian states. This means that EAS will be the subject of ongoing political debate in parliaments around the country. As noted earlier, it is neither academics nor lobbyists who will determine whether the law on this topic changes, but rather politicians. Yet to date there has been insufficient scrutiny of the political debates about this issue and the associated arguments that have been advanced for often staunchly-defended political positions. This article addresses that gap. It comprehensively charts those debates by outlining the wide range of arguments that politicians have used to make the case for and against reform. By providing an evidence base about how politicians debate this vexed issue, we assist scholars, activists, lobbyists, politicians and the wider community to engage more deeply in Australia’s EAS debate and thereby facilitate the scrutiny and critical review to which our law-makers’ discussions should be subject. Annexure A provides an outline of politicians’ arguments for and against EAS.

There is not scope in this paper to critically analyse the quality of the arguments nor the evidence upon which they are based. But we will make one comment in conclusion. Many of the arguments advanced by politicians on both sides of this debate are highly contentious. Consider, for example, the ‘religious SOL’ argument, or the secular ‘suffering is ennobling’ argument. These arguments represent personal beliefs that not everybody in our community shares. We will call arguments about EAS, based on personal beliefs of this kind, Personal Matters. These Personal Matters represent beliefs about which people can reasonably disagree. While some people might think that these Personal Matters provide decisive reasons against EAS, others will not believe this. We should ask: may parliament allow these Personal Matters to serve as cogent grounds for not legalising EAS? Bear in mind that legislation will apply to all people in the relevant community, and not just those people who hold these particular views. Although such Personal Matters should be represented in parliamentary debates to reflect the variety of views held by the wider community, we do not believe that such Personal Matters should form the basis for rejecting legislative change. It is better for people to be free to make up their own minds, in their own case, about whether these Personal Matters are decisive grounds for them not to avail themselves of EAS. We suggest that parliaments should remain neutral about Personal Matters. These Personal Matters are not legitimate grounds against legalising EAS, for in keeping EAS unlawful on those grounds, the parliament would be taking a substantive position – a personal view of its own – about which people can rationally disagree, and this arguably oversteps the legitimate role of the parliament.[263]