University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

WHAT DO TRIAL JUDGES CITE? EVIDENCE FROM THE NEW SOUTH WALES DISTRICT COURT

RUSSELL SMYTH[*]

This article examines the citation practice of the New South Wales District Court, using all decisions reported on AustLII/Caselaw NSW decided between 2005 and 2016. This study is the first to examine the citation practice of an ‘inferior’ trial court. The study suggests some important differences between the citation practice of the New South Wales District Court and what existing studies have found about the citation practice of superior courts in Australia. The proportion of citations to decisions of the High Court and New South Wales Court of Appeal is higher than in the superior courts. The proportion of citations to the Court’s own previous decisions are lower than in the superior courts. The proportion of coordinate citations to courts in other states at the same level in the judicial hierarchy are extremely small. The Court cites fewer secondary sources than is the case in the appellate courts.

Judges are required to explain the reasons for their decisions and, whenever possible, to provide written reasons.[1] Written judgments typically contain citations to various sources, including case law, secondary sources such as encyclopaedias, journal articles and treatises, as well as legislation. Documenting and analysing what judges cite in their reasons for a decision ‘potentially open[s] a window to better understanding of judicial decision-making, the development of the law [and] use of precedent’.[2] While we are unable to peer inside the judge’s mind at the time of decision, written reasons, together with citations, ‘show what judges think is legitimate argument and legitimate authority, justifying their behaviour’.[3]

The first study of a court’s citation practice was of the judgments delivered by the California Supreme Court in 1950.[4] Since then, the citation practice of courts in Canada[5] and the United States[6] has been extensively studied over a 70-year period. There are now also several studies of the citation practices of superior courts in Australia, including the High Court,[7] the Family Court,[8] the Federal Court[9] and state supreme courts.[10] Relatedly, there are also studies that use citation analysis to measure the influence or prestige of Australian judges and what determines that influence or prestige,[11] as well as the ‘productivity’ of Australian judges over the course of their judicial careers.[12] Recent studies

by Kieran Tranter and co-authors have extended citation analysis of

Australian courts to examine the citation practice of law reform bodies, such

as the Australian Law Reform Commission,[13] the Queensland Law Reform Commission[14] and the Productivity Commission.[15] Studies of the citation practice of courts in common law countries other than Australia, Canada and the United States, however, are relatively few in number.[16]

I add to the literature on the citation practice of Australian courts through presenting a study of the citation practice of the New South Wales District Court (‘District Court’), based on all decisions reported on the Australasian Legal Information Institute (‘AustLII’) and the NSW Caselaw databases decided between 2005 and 2016.[17] The District Court, in its current form with state-wide civil and criminal jurisdiction, was established by the District Court Act 1973 (NSW).[18] It is a trial court, but also has jurisdiction to hear appeals from the Children’s Court and Local Court.[19] The District Court has jurisdiction to hear all criminal offences, apart from murder, treason and piracy. In its civil jurisdiction, the District Court may deal with all motor accident cases irrespective of amount claimed, equitable claims or demands for recovery of money or damages not exceeding $750 000 and other claims up to $750 000.[20] It may also deal with matters exceeding this upper limit with the consent of the parties.[21] The District Court, which is an intermediate court in the New South Wales judicial hierarchy,[22] is a first tier inferior court in the hierarchy of courts in Australia.[23]

I contribute to the literature on judicial citation practice and, more generally, judicial decisions through examining the citation practice of an ‘inferior’ trial court. The duty to give reasons extends to trial judges sitting in inferior courts. The rationale is couched either in terms of the importance of reasons being available to facilitate appellate review or, more broadly, as an aspect of the open justice principle.[24] There is a growing trend for many courts and tribunals in Australia, from all tiers in the judicial hierarchy, to publish at least a proportion of their judgments online. This may typically either be on the website of the court or tribunal and/or through websites such as AustLII. These provide a ready means with which one can analyse judicial citation practice. The District Court provides an ideal setting in which to situate a study of such a court, given that it is the largest trial court in Australia.[25]

There are several reasons why providing, and analysing, data on the citation practice of an inferior court, such as the District Court, is important. One reason is that while most empirical research has centred on the appellate courts, it is the inferior trial courts that hear the bulk of the cases. Most people who interact with the courts do so through the local/magistrates court or through the county/district court. If it is important to understand the citation practice of superior courts because it assists us to learn about how decisions are crafted (given that most people who interact with the legal system do so through engagement with inferior courts and tribunals), it seems equally important to understand citation practice, and by extension, judicial reasoning in these courts. Yet, very little such empirical research exists. Writing about the situation in the United States, Lawrence Friedman and Robert Percival suggest:

American scholarship has lavished most of its attention on appellate courts, paying little attention to courts on the bottom rungs of the ladder ... But the trial court is the court with the most direct contact with the man in the street, for both civil and criminal matters. Here he meets the law face-to-face. And, although federal courts are certainly important, state trial courts handle by far the larger volume of work.[26]

Friedman and Percival were writing four decades ago and this is no longer the case with respect to scholarship in the United States.[27] Their observations, however, still apply to current Australian scholarship on the courts. To this point, there are no studies of the citation practice of inferior trial courts and few studies of decision-making on inferior courts in Australia more generally.[28] This is an important gap in the literature that I seek to address.

Publicly accessible online decisions of courts, such as the District Court, replete with citation to authority, potentially provide insights into what influences judicial reasoning in busy trial courts, and how the case law that evolves in the superior courts is interpreted and applied when ‘the man in the street ... meets the law face-to-face’.[29] To emphasise the point, it is important to understand how the case law developed in the appellate courts is applied in the reasoning of the lower courts, given that the latter hear most of the cases.

Another reason why studying the citation practice of the District Court is important is that it provides a completely different institutional context to consider how citations are used. In this respect, the District Court is likely to throw up some interesting contrasts to the citation practices of the superior courts. Inferior courts are likely to see their role as resolving specific disputes, rather than making policy. Hence, one would expect them to cite less secondary sources and, in particular, law reviews than the High Court or Courts of Appeal.[30] For the same reason one would expect them to cite far less case law from outside Australia. A previous study found that the state supreme courts cite far fewer foreign decisions than the High Court, as a proportion of total citations.[31] The reason why the High Court has cited a relatively high proportion of foreign decisions since the Australia Acts[32] and its decision in Cook v Cook[33] is the search for guidance in the development of what Sir Anthony Mason has termed ‘development of a distinct Australian law’.[34] It has been suggested that the explanation for the much lower citation rates to foreign cases on the state supreme courts is that judges sitting on these courts do not have the same overt policymaking role and are more likely to feel constrained by traditional precedent than the High Court.[35] One would expect these observations to apply a fortiori to judges of the District Court.

One would conjecture there to be fewer citations in the District Court because it is commonly concerned with determining issues of fact against a background of well understood legal principle. Hence, it is not extending the boundaries of legal principles in the manner appellate courts do. There are also other institutional differences that bear on citation practice. There are likely to be time pressures on decision-making in the District Court that restrict the time available for detailed reasons and extensive citation to authority compared with the appellate courts. The District Court is unlikely to have the same resources available to the appellate courts and the cases that they hear will not be as complex. Many of the issues considered by the District Court are procedural and procedural issues may be less likely to provoke citation – and to the extent they do generate citations, different citations – than substantive issues. All of this suggests that the District Court may cite fewer authorities overall.

The remainder of the article is set out as follows. Part II provides an overview of the various forms of citation and examines the role of stare decisis in the District Court. Part III introduces, and describes, the dataset in more detail, including how the data were collected. I discuss overall trends in citations on the District Court in Part IV. Part V examines the types of authorities that get cited and considers the findings in light of results for other courts. I consider the findings for individual judges in Part VI and examine the specific legal books and legal periodicals that the Court cites in more detail in Part VII. The final section concludes.

I adopt the taxonomy for classifying citations in judgments suggested by Peter McCormick, who is the author of several studies of the citation practice of Canadian courts.[36] McCormick suggests that there are five types of judicial citations, namely, consistency citations, hierarchical citations, deference citations, coordinate citations and citations to secondary sources (such as books and law review articles). I consider each of these in turn.

Consistency citations are citations to the Court’s own previous decisions. As McCormick describes it, ‘the general principles of continuity and consistency, and the legal value of predictability in the law, require that [a court’s own previous decisions] carry considerable weight’.[37] The preferable view appears to be that the District Court is not bound by its own previous decisions. W L Morison expresses the rationale for this as follows:

Decisions below the level of the Court of Appeal, for example, decisions of single judges of the Supreme Court, or decisions of district court judges, are not binding as a matter of precedent on other judges. Since the decisions of the district court judges and single judges of the Supreme Court are generally subject to appeal immediately to the New South Wales Court of Appeal that court is, as it were, the lowest ‘correcting’ court in the hierarchy.[38]

The main authority on this point is the District Court case, Keramaniakis v Wagstaff,[39] in which Rein DCJ applied the logic in the above passage in concluding that he was not bound to follow a decision of a single judge of the New South Wales Supreme Court (and by analogy a previous decision of the District Court).[40] The decision on this point in Keramaniakis v Wagstaff has been followed in the subsequent District Court cases of LU v Registrar of Births Deaths and Marriages [No 2][41] and Workers Compensation Nominal Insurer v Brasnovic.[42] In both cases, while Taylor DCJ concluded that he was not bound by previous District Court decisions, he took the view that unless he had no doubt that the earlier District Court decision was wrong, he should still follow it for reasons of judicial comity.[43]

Hierarchical citations are citations to courts to which an appeal lies from the District Court. The District Court is bound by the ratio decidendi of decisions of the High Court and New South Wales Court of Appeal.[44] Matthew Harding and Ian Malkin consider the effect of the High Court decision in Farah Constructions Pty Ltd v Say-Dee Pty Ltd[45] on the status of obiter dicta of the High Court and conclude that since Farah, the lower courts have generally felt obliged to follow High Court dicta.[46] This reflects the position in the District Court, in which, since Farah, judges of the District Court have typically felt themselves bound by obiter dicta of the High Court. For example, in Lassanah v New South Wales[47] Gibson DCJ considered obiter dicta of the High Court in Mann v O’Neill.[48] Her Honour states: ‘[e]ven if, rather than forming a part of the ratio decidendi, this [passage] amounts to “considered obiter dicta”, I am still bound by this decision for the reasons explained by the High Court in Farah’.[49]

Deference citations are citations to decisions of courts higher in the judicial hierarchy, or in a parallel hierarchy, that are not binding, but are of persuasive value. Apart from citations to cases in which the ratio decidendi of a decision of the High Court or New South Wales Court of Appeal is indistinguishable, as well as probably citations to obiter dicta of the High Court, which constitute hierarchical citations, all other District Court citations to Australian superior courts are deferential citations. In Keramaniakis v Wagstaff,[50] while concluding he was not bound by a single judge of the Supreme Court, Rein DCJ stated:

I accept, of course, that any decision of a single judge of the Supreme Court is entitled to considerable respect and ought be followed unless after due consideration of it, this Court is convinced that it is wrong, for example because some relevant matter or case was not brought to the Supreme Court judge’s attention. I would regard that principle, which might be described as a broad principle of comity, as extending to judgments of all Australian Superior Courts.[51]

This general principle has been accepted in a number of subsequent decisions in the District Court.[52] Since the Australia Act 1986 (Cth), Australian courts are not bound to follow decisions of the House of Lords/United Kingdom (‘UK’) Supreme Court or the English Court of Appeal, although such decisions continue to be given respect.[53] The High Court is not bound by any decision of the Privy Council whether given before, or after, the Australia Act 1986 (Cth).[54] In Alamdo Holdings Pty Ltd v Bankstown City Council,[55] Gzell J expressed the view:

Once the Privy Council ceased to be part of the hierarchical structure of the Australian courts, the same considerations that led the High Court to conclude it was no longer bound by Privy Council decisions should apply equally to other courts in Australia.[56]

Hence, citations to English decisions, including decisions of the Privy Council, and decisions of courts in other foreign jurisdictions, are also deferential citations.

Coordinate citations are citations to the decisions of other courts at the same tier in the judicial hierarchy. Coordinate citations in the District Court are to decisions of district courts in other states and the County Court in Victoria. While such decisions are not binding on the District Court, Australia has a single common law[57] and coordinate citations promote consistent interpretation in common law cases and cases involving uniform national legislation. In Valentine v Eid,[58] Grove J was of the view that although a county or district court is presided over by a judge, only judgments of a superior court could contribute to the common law.[59] This view was largely premised on the reporting of county and district court judgments being erratic and, thus, not a reliable source of precedent in the early 1990s.[60] This justification, though, is less salient a quarter century later, with the widespread availability of the decisions of the district courts and County Court in Victoria being online. Grove J also suggested: ‘It is notorious that the formidable caseload in the District Court necessarily demands frequent ex tempore judgment which does not suggest itself as a source for systematic derivation of precedent’.[61] That the district courts, and County Court in Victoria, deliver a large number of ex tempore judgments, however, should not mean that those judgments which are published have no precedent value. One only has to look at the United States courts of appeals where ‘nearly 80 per cent of all dispositions ... [are] unpublished [and] erratically distributed’,[62] but the other 20 per cent of opinions that are published are given full precedent value.

Secondary sources include dictionaries, journal articles, law reform reports, legal encyclopaedias and legal books. Secondary sources are not binding on any court. Various reasons, nonetheless, have been offered for why judges cite secondary sources.[63] One reason is convenience. The author of a journal article or legal text may summarise the law, particularly the law in another jurisdiction, together with citation to the relevant case law, and it is convenient for the judge to adopt it as a correct statement of the law. A second reason for citing secondary sources is to examine academic opinion on the development of the law or for statements about what directions future developments in the law should take. A third reason is to refer to the views of well-respected academics in deciding what earlier cases decided. A fourth reason is to draw on the opinion of other judges, writing extra-judicially. Fifth, some secondary sources are cited because previous cases have stated that they correctly represent the law. A sixth reason for citing secondary sources, particularly non-legal sources, is to examine the scientific or social science underpinnings of legal rules or examine the basis of expert evidence.

Some of these reasons are likely to be more important in the District Court than others. The District Court, by comparison to superior courts such as the High Court or Court of Appeal, is more concerned with the establishment of fact than the development of legal policy or extending legal principle. Thus, citing secondary sources, in order to trace the evolution of legal principle or explore suggestions for law reform is likely to be less important. At the same time, if a High Court judge has written extra-judicially on a topic, a District Court judge may well cite that source in ascertaining the relevant point of law. For example, if Sir Anthony Mason has expressed a view on a point of law extra-judicially, for which the case law is unclear, it is very likely that a judge of the District Court will treat it with the greatest of respect. In addition, it is likely that the District Court will have what William Manz terms its ‘local favourites’.[64] These are ‘local works’, such as Ritchie’s Uniform Civil Procedure NSW, that summarise the applicable law and rules in New South Wales.[65] A further consideration is that the District Court hears a lot of matters in which points of procedure are important. Thus, one would expect many of the local favourites to be convenience citations to summaries of local procedure.

Judicial attitudes toward citing secondary sources are varied. In the United States, most judicial statements have centred on the value, or otherwise, to judges of the scholarship contained in law review articles. Several United States’ judges, including judges of the stature of Cardozo, Hughes and Warren have said that they find law reviews useful when crafting their opinions.[66] More recently, however, Judge Harry Edwards was more critical of law reviews, writing:

The schools should be ... producing scholarship that judges, legislators, and practitioners can use ... But many law schools – especially the so called ‘elite’ ones – have abandoned their proper place, by emphasizing abstract theory at the expense of practical scholarship and pedagogy.[67]

The current Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court, John Roberts, caused a stir in 2011, when speaking at a judicial conference he echoed Judge Edwards’ remarks:

Pick up a copy of any law review that you see, and the first article is likely to be, you know, the influence of Immanuel Kant on evidentiary approaches in 18th Century Bulgaria, or something ... If the academy wants to deal with the legal issues at a particularly abstract and philosophical level, that’s great and that’s their business, but they shouldn’t expect that it would be of any particular help or even interest to the members of the practicing bar or judges.[68]

Richard Re, however, found that despite the Chief Justice’s comments, he actually regularly cites law review articles in his opinions. After compiling a list of the law review articles that Chief Justice Roberts cited in his opinions, Re concludes:

The listed cites likely understate the Chief’s interest in law reviews, since he presumably considers many materials that, for one reason or another, don’t actually end up appearing in his published opinions ... The fact that law review citations regularly appear in the Chief Justice’s judicial opinions casts the Chief’s famous critique of law reviews in a different light. Instead of taking the position that law reviews are generally irrelevant to the Court’s business, perhaps the Chief meant to convey that law reviews could or should be relevant to courts even more often than they currently are.[69]

Most senior Australian judges have been supportive of referring to academic opinion in judgments.[70] Sir Garfield Barwick has expressed the contrary view that:

Citation of [academic sources], however eminent and authoritative, may reduce the authority of the judge and present him as no more than a research student recording by citation his researched material ... [When this occurs, judgments] can become an exercise in essay-writing rather than the statement of reason for an authoritative judgment.[71]

The data presented in this study was compiled by counting citations to case law and secondary sources in all decisions of the District Court reported on AustLII/NSW Caselaw decided between 2005 and 2016. Over this period there were a total of 3266 cases reported on AustLII/NSW Caselaw.[72] Each of the 3266 cases was read by one of two research assistants, working under my supervision over the period June 2016 to February 2017. For each case, the research assistants recorded the name of the case, year and citation of the case, presiding judge, broad subject area, number of paragraphs and citations in the judgment to primary and secondary sources on a separate worksheet for each case. Among secondary sources, the author and title of texts and journal articles were also recorded on the worksheet. I read 300 cases (approximately 10 per cent of the sample) at random once the data were collected for all the cases to provide a spot check on the accuracy of the recorded information. The recorded information was completely accurate in 298 of the 300 cases. In the other two cases, the discrepancy between what the research assistants recorded and what I independently recorded was very minor, suggesting a low overall margin of error. Once worksheets were compiled for each case, I used this information to compile the tables reported later in the article.

The decision to publish decisions on NSW Caselaw, and, thus, AustLII, is

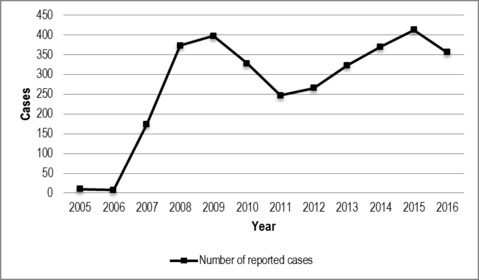

at the discretion of each individual judge.[73] A number of factors potentially influence which judgments get published. Based on analysis of data, a study of the County Court of Victoria found a relationship between the judge’s age, if the judge had an adjunct appointment at a university, the judge’s administrative workload, if the judge was on the work cover list, and the judgments he or she published on the Court’s website.[74] One imagines that the potential precedent value of the decision would also be an important factor affecting whether a judgment was published online. Figure 1 shows the number of District Court cases reported on NSW Caselaw and, hence, AustLII in the sample for each year between 2005 and 2016. In 2005 and 2006 the numbers are very small, but the number increased to 174 in 2007 and between 2008 and 2016 there was in excess of 300 judgments on AustLII each year, with the exception of 2011 and 2012, when there were 247 and 266 decisions respectively.

Figure 1 – Number of District Court cases reported in AustLII/NSW Caselaw, 2005–2016

Over the period 2005 to 2016 there were approximately 6000–8000 civil matters and criminal trials finalised by the Court most years.[75] Hence, for most years my sample is around 4–5 per cent of cases disposed or finalised. This compares favorably to previous citation studies for superior courts in Australia and Canada that have typically relied on cases reported in the authorised law reports. One might always argue that to get a more complete picture of the Court’s citation practice, one should also consider judgments not reported on AustLII. But, to consider judgments not recorded on AustLII has its own problems. Given the way the data was collected – using research assistants to read each case – the monetary cost of collecting citations on 3266 cases was high. Collecting data on further cases not reported on AustLII would potentially be prohibitive. And, then there would be the issue of deciding which unreported cases to include, which might invite criticism of subjectivity bias. The total sample size of over 3000 cases is certainly larger than that used in previous citation studies of Australian courts, even those that sample over a longer timeframe. For example, the state supreme court citation studies that examined citations at decade intervals between 1905 and 2005 typically had 600–900 cases in total, depending on the specific state supreme court being examined.[76] While only a small proportion of total cases finalised are published on AustLII, to quote Peter McCormick, District Court cases published online ‘probably include a very high proportion of all the decisions important [enough] to call for a reasoned judgment based on authority’.[77]

Consistent with previous citation studies, citations to constitutions, regulations and statutes were not counted. The reason for adopting this approach is that the subject matter of the case often dictates citations to these sources and, as such, citations to these sources are not a matter of judicial discretion.[78] If a case or secondary source was cited multiple times in the same paragraph it was counted only once, but if it was cited in a subsequent paragraph it was counted once for each paragraph in which it was cited. The rationale for so doing is that the judge is assumed to be making a different point each time.[79] I make no distinction between positive and negative citations. There are two reasons for this. One is that I am interested in examining whether a case, or secondary source, influences the judge’s reasoning. Given that citing a source is purely an act of discretion, if a case, or secondary source, is cited it is reasonable to conclude that it has influenced the judge’s thinking, irrespective of whether the citation is positive or negative.[80] The other reason is that, in contrast to academic writing, in which the extant literature may be heavily criticised, judicial politeness dictates that few judicial citations are, in fact, negative.[81] For example, previous research suggests that less than one half of 1 per cent of citations in the Supreme Court of Canada are negative[82] and that less than 10 per cent of citations in the United States courts of appeals are negative.[83]

Table 1 shows the subject matter of the decisions in the dataset. Criminal law accounts for 45 per cent of cases in the sample, followed by torts (17 per cent), procedure (9 per cent), contracts (5 per cent) and evidence (3 per cent). The high proportion of criminal law, evidence and procedure cases in the District Court – together almost 60 per cent of District Court decisions published on AustLII – reflects the Court’s broad criminal jurisdiction and the large number of criminal trials that it conducts. The caseload composition of the District Court is similar to that of the state supreme courts in recent years, with criminal law and evidence and procedure being mainstays on the dockets of those courts.[84] However, the proportion of criminal cases in the state supreme courts, at just under one third of all cases in 2005, is slightly less than that of the District Court.[85]

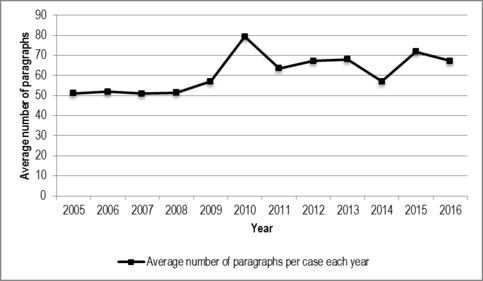

Figure 2 – Average number of paragraphs per case in District Court cases reported in AustLII/NSW Caselaw, 2005–2016

Figure 2 shows the average length of judgments, denoted by the number of paragraphs per case, over the period 2005–16. The average length of a case seems a reasonable proxy for case complexity. One would expect that more complex cases would reflect more paragraphs. There does not appear to be much difference in case complexity, proxied by judgment length, over time. The minimum average number of paragraphs was 51 in 2005 and the maximum average number of paragraphs was 79.4 in 2010. However, 2010 was an outlier. In all other years, the average length is in the range of 50–70 paragraphs per case.

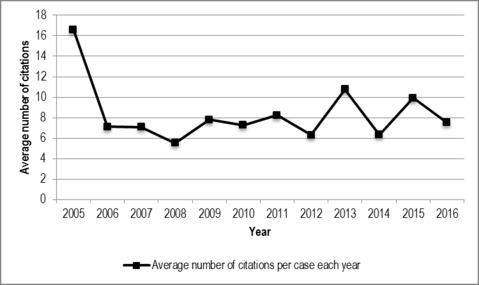

Figure 3 shows the average number of citations per case over the period 2005–16. The outlier is 2005, in which there were 16.6 citations per case, but not much can be gleaned from this given the small number of published cases that year. In other years, average citations varied between a minimum of 5.6 (2008) and maximum of 10.8 (2013). The median number of average citations by year was 7.3 citations in 2010. One might expect there to be a positive relationship between case complexity, proxied by the average length of the case, and the average number of citations per case. However, this is not really borne out in the data. For instance, in 2010 the Court published the longest judgments, but citations per judgment were average. The average number of citations in the District Court is lower than the average number of citations per case in the state courts of appeal or the High Court. For example, the median average citation rate by year in the District Court over the period 2005–16 was about one third the average citation rate per judgment in the New South Wales Court of Appeal in 2005[86] and about one-sixth the average citation rate in the High Court in 1996.[87] This comparison most likely reflects differences in case complexity and work load between trial and appellate courts. The appellate courts hear fewer cases, but, at the same time, the cases that they hear are more difficult. As Kirby J has written, in the High Court ‘everything is hard. In the High Court of Australia, with very few exceptions, all of the cases are difficult’.[88] While the data for the District Court in this study seems to suggest no relationship between case length and citations per case, it is likely that the much higher citation rate in the High Court reflects the trend in that Court toward longer, more discursive judgments in the 1990s.[89]

Figure 3 – Average number of citations per case in District Court cases reported in AustLII/NSW Caselaw, 2005–2016

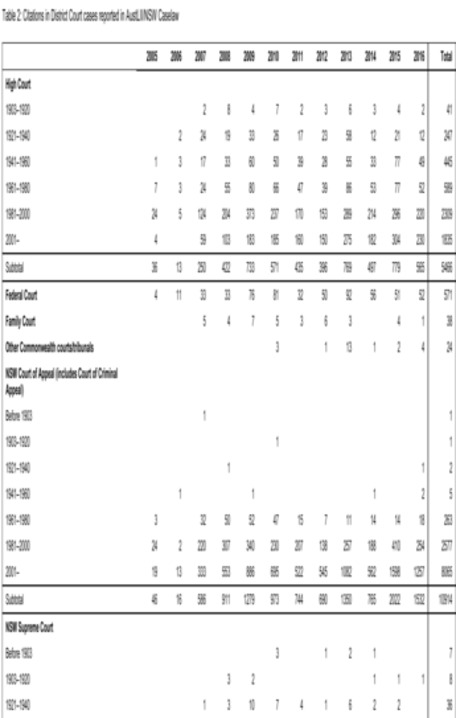

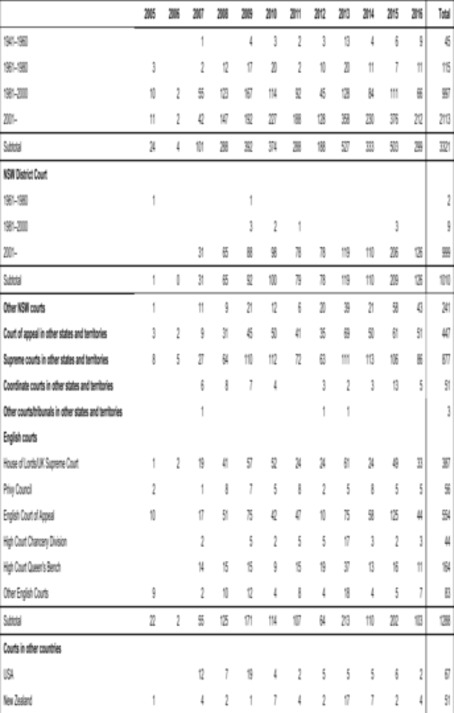

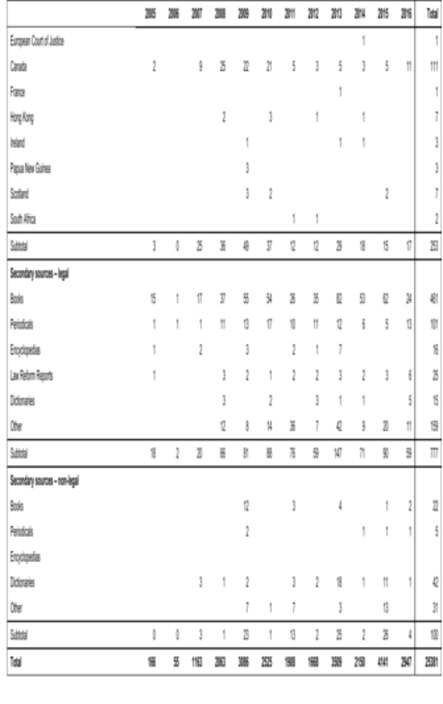

Table 2 presents a breakdown of citations in District Court cases reported on AustLII/NSW Caselaw over the period 2005–16. Table 3 provides a summary of the findings in Table 2 in terms of the taxonomy of citation types presented in Part II.

Table 3: Taxonomy of citation types in District Court cases reported in AustLII/NSW Caselaw

|

Type of Citation

|

Percentage of total citations

|

|

Consistency citations

|

3.98%

|

|

Hierarchical citations

|

|

|

High Court

|

21.54%

|

|

NSW Court of Appeal

|

43%

|

|

|

64.54%

|

|

Coordinate citations

|

0.2%

|

|

Deferential citations

|

|

|

NSW Supreme Court

|

13.09%

|

|

Other Australian courts

|

8.6%

|

|

English courts

|

5.08%

|

|

Courts in other countries

|

1%

|

|

|

27.77%

|

|

Secondary sources

|

3.5%

|

Notes: Percentages do not add to 100 because of rounding.

Several observations are possible based on Tables 2 and 3. First, hierarchical citations to decisions of the High Court and New South Wales Court of Appeal constitute just under two thirds of total citations (64.54 per cent). Between the High Court and New South Wales Court of Appeal, the District Court cites the New South Wales Court of Appeal twice as much as the High Court. This finding likely reflects the greater stock of precedent in the Court of Appeal.

Second, following hierarchical citations, deferential citations are the second largest form of citation. Deferential citations represent 27.77 per cent of total citations. Most deferential citations are to decisions of the New South Wales Supreme Court (13.09 per cent of total citations), followed by citations to decisions of other Australian courts (8.6 per cent of total citations), decisions of English courts (5.08 per cent of total citations) and decisions of courts in countries other than Australia or England (1 per cent of total citations).

Third, citations to decisions of English courts, as a proportion of total citations, declined in the District Court from 2005 to 2016.[90] This trend demonstrates a continuation of the decline in the proportion of citations to English decisions observed in previous studies of the state supreme courts over the twentieth century.[91] In 2005, the most recent year for which there is data, citations to decisions of English cases constituted 16.9 per cent of total citations in the New South Wales Supreme Court.[92] In 2005, decisions of English courts represented 13.25 per cent of total citations in the District Court, but by 2016 this proportion had fallen to 3.4 per cent. There are several reasons for falling citation rates to English decisions, including the growth in the importance of statute law, UK membership of the European Union, which made English law less relevant to Australia, and the increasing influence in the UK of the European Convention on Human Rights[93] since the Human Rights Act 1998 (UK).[94]

Fourth, while deferential citations to courts in countries other than Australia or England represent just 1 per cent of total citations, such citations are dominated by courts in three countries. Together, courts in Canada (43.9 per cent), the United States (26.5 per cent) and New Zealand (20.2 per cent) constitute 90 per cent of such citations. Courts in these three countries are also the largest suppliers of citations to the state supreme courts outside of Australian and English courts.[95] This is certainly the case in the New South Wales Supreme Court.[96] Hence, the District Court seems to be taking its cue from the New South Wales Court of Appeal and the state supreme courts more generally in this respect.

The importance of Canada, New Zealand and the United States as suppliers of citations to Australian courts outside of England is due to several factors.[97] The United States is a major supplier of precedent to the world, reflecting its economic and political importance as a global superpower.[98] David Zaring suggests that economic ties might be important when judges choose which foreign precedent to cite.[99] The United States is Australia’s second, and New Zealand is Australia’s sixth, largest trading partner.[100] Canada and New Zealand share strong historical ties with Australia as British Commonwealth countries and the defence alliance with the United States has become increasingly important to Australia since World War II.

Fifth, consistency citations to the Court’s previous decisions are only about 4 per cent of total citations and much less than either hierarchical or deferential citations. Consistency citations in the District Court are much lower than either the New South Wales Supreme Court[101] or the High Court.[102] This finding likely reflects two factors. One is that previous studies of appellate courts in Australia, Canada and New Zealand have generally found that hierarchical citations form a higher proportion of total citations than consistency citations.[103] As an inferior court, there will be a larger stock of citable cases from courts higher in the judicial hierarchy than is the case for an appellate court. Two, the District Court largely only cited its own previous decisions that are published online. Citations to cases decided since 2001, when the Court first published its decisions online, represented 98.7 per cent of consistency citations. This suggests, given that the number of decisions published on AustLII before 2007 were very small, the stock of citable decisions of the District Court to which the judges had systematic access was likely to be small.

Sixth, coordinate citations were miniscule, representing just 0.2 per cent of total citations. This is much lower than the state supreme courts, for which coordinate citations represent 14–15 per cent of total citations.[104] There are two reasons for this finding. One is that, similar to the District Court, the district courts in other states and the County Court in Victoria have only relatively recently started putting decisions online, making them more accessible. The other is the view of Grove J in Valentine v Eid,[105] discussed above, that only decisions of superior courts have precedent value and contribute to the development of the common law.[106] While it was submitted above that the rationale for this view is no longer valid, to the extent that it holds sway, decisions of other inferior courts at the same tier will be less likely to be cited.

Seventh, citations to secondary sources represented 3.5 per cent of total citations. This figure is lower than the New South Wales Supreme Court, in which secondary sources represent approximately 6 per cent of citations in 2005[107] and the High Court, in which citations to secondary sources was 10.5 per cent of citations in 1996.[108] As suggested in the introduction, this finding is consistent with the expectation that secondary sources are cited more

when a court sees its role as making policy, while the District Court is more likely to see its role as resolving specific disputes between the parties.[109] Another consideration is that the District Court is, more often than not, concerned with establishing issues of fact, rather than extending the breadth of legal doctrine. Thus, the Court may be less likely to consult secondary authorities with a view to getting different interpretations on the meaning of contested legal principle.

Citations to legal secondary sources constituted 88.59 per cent of total secondary source citations. This figure is similar to that in other courts in Australia and New Zealand.[110] The probable explanation for this result is, as Friedman et al put it: ‘Old habits of citation persist, no doubt, because judges feel that only “legal” authorities are legitimate’.[111]

A final observation regarding Table 2 is that, in addition to its own decisions, the Court favoured more recent decisions of the High Court, New South Wales Court of Appeal and New South Wales Supreme Court. This is a common finding in citation studies and reflects that precedent depreciates over time.[112] There are several reasons for the depreciation of legal precedent. These include that some older cases get overruled, that more recent cases are often more relevant on the facts because the social context has changed and that legal opinion changes over time so that, even if not overruled, older cases may be less persuasive.[113]

Table 4 presents information on the citation practice of individual judges in each of the years considered. Conclusions about the citation practice of individual judges are difficult to make because, in any given year, there are several judges with only a few published judgments.[114] This said, at a general level, what can be concluded is that citation rates differ markedly between judges. I present some information on who the heavy and meagre citers were, while emphasising that the reason for doing so is simply to note that divergent patterns exist. I do not draw conclusions about whether citing more or less represents a good practice.

Table 4: Average citations for each judge in District Court cases reported in AustLII/NSW Caselaw

|

2005

|

2006

|

2007

|

2008

|

|

Norrish 28 (2)

Rein 18.8 (5)

Berman 11 (1)

Murrell 2.5 (2)

|

Rein 22 (1)

Johnstone 9 (2)

Goldring 4.7 (3)

Nicholson 1.5 (2)

|

Walmsley 36.7 (3)

Gibson 33.4 (7)

Hungerford 26.5 (2)

Knox 25.4 (5)

Phegan 16.8 (5)

Norrish 16.2 (5)

Blanch 15 (1)

Williams 13.8 (5)

Rein 12 (1)

Neilson 10.4 (8)

McGrowdie 9 (1)

Rolfe 8 (2)

Toner 7 (1)

Johnstone 7 (7)

Goldring 5.4 (5)

Conlon 4.6 (7)

Balla 4 (1)

Nicholson 3.8 (25)

Cogswell 2.1 (58)

Sidis 0.5 (8)

Berman 0.2 (10)

Finnane 0.2 (5)

Nield 0 (1)

Murrell 0 (1)

|

Gibson 18.1 (29)

Hungerford 16.7 (6)

Knox 12.7 (12)

Norrish 11.9 (8)

Rein 11 (1)

Donovan 10 (1)

Neilson 9.7 (3)

Phegan 9.3 (3)

Levy 9.3 (12)

Johnstone 8.9 (23)

Hulme 8.6 (7)

Elkaim 6.3 (3)

Nicholson 4.6 (45)

Bennett 4.6 (7)

Williams 4.5 (6)

Conlon 4 (2)

Murrell 3.9 (19)

Rolfe 3.1 (23)

Goldring 3 (25)

Garling 3 (1)

Cogswell 2.1 (44)

Blackmore 2 (1)

Nield 1.7 (3)

Berman 1.6 (39)

Finnane 1.4 (7)

Sidis 1.2 (41)

Truss 1 (2)

|

|

Weighted average:

15.1

|

9.3

|

10.8

|

6.5

|

Notes: Figures in parenthesis are the number of judgments.

Table 4 continued

|

2009

|

2010

|

2011

|

2012

|

|

Woods 34 (1)

Walmsley 27 (2)

Gibson 25.6 (25)

Neilson 16 (1)

Norrish 15.5 (10)

Knox 15.4 (13)

Bozic 13.8 (4)

Conlon 13 (1)

Levy 12.2 (31)

Hungerford 12.2 (17)

Elkaim 12 (4)

Toner 12 (2)

Bennett 9.8 (6)

Goldring 9.05 (22)

Colefax 9 (1)

Murrell 8.6 (17)

Williams 8.5 (14)

Johnstone 8 (10)

Armitage 8 (3)

Truss 8 (1)

Rolfe 7.5 (11)

Garling 6 (1)

Sweeney 5 (1)

Nicholson 4.6 (37)

Phegan 3 (1)

Cogswell 2.7 (72)

Sidis 2.5 (39)

Berman 1.6 (48)

Finnane 0 (2)

Ainslie-Wallace 0 (1)

|

Gibson 19.2 (40)

Levy 15.1 (28)

Hungerford 14.6 (7)

Elkaim 14 (1)

Norrish 13.3 (9)

Blackmore 13 (1)

Johnstone 12.3 (18)

Puckeridge 12 (1)

Rolfe 11 (4)

Knox 9.8 (4)

Bozic 9 (5)

Lakatos 7.5 (2)

Williams 7.3 (3)

Walmsley 7 (1)

Bennett 6.3 (3)

Murrell 4.9 (8)

Truss 4.8 (4)

King 5 (3)

Garling 5 (3)

Phegan 5 (1)

Neilson 5 (1)

Colefax 4 (1)

Nicholson 3.4 (39)

Sidis 2.9 (29)

Cogswell 2.2 (42)

Tupman 2 (3)

Berman 1.7 (56)

Finnane 1.4 (8)

Haesler 1.3 (3)

|

Lakatos 30.5 (2)

Norrish 28 (4)

Walmsley 23.3 (4)

Gibson 22.3 (14)

Olsson 20 (2)

Letherbarrow 19.7 (6)

Levy 15.3 (26)

Knox 12.3 (4)

King 12 (2)

Truss 12 (1)

Toner 10.7 (3)

Finnane 10.3 (4)

Tupman 10.3 (3)

Neilson 9.2 (9)

Haesler 8 (9)

Woods 8 (4)

Murrell 7.9 (9)

Johnstone 7.4 (11)

Sidis 6.9 (10)

Colefax 6.2 (5)

Elkaim 5.9 (13)

Garling 4 (3)

Nicholson 3.8 (6)

Sidis 2.5 (2)

Cogswell 2.4 (49)

Berman 1 (39)

Freeman 1 (1)

Ashford 1 (1)

Conlon 0 (1)

|

Gibson 17.1 (35)

Haesler 10.4 (5)

Letherbarrow 14.7 (3)

Williams 12 (1)

Rolfe 10 (1)

Olsson 9 (1)

Knox 8.3 (6)

Johnstone 8 (5)

Marks 7.7 (3)

Levy 7.6 (31)

Norrish 7.5 (12)

Mahony 7.3 (11)

Taylor 6.7 (21)

Nicholson 5.3 (4)

Blackmore 5 (1)

Neilson 4.5 (17)

Colefax 4.3 (3)

Elkaim 3.7 (11)

Murrell 2.8 (11)

Finnane 2.5 (2)

Cogswell 2.1 (32)

Sorby 1 (1)

Sidis 1 (1)

Berman 0.5 (45)

Blanch 0 (1)

Curtis 0 (1)

Biscoe 0 (1)

|

|

Weighted average:

10.4

|

7.6

|

10.4

|

5.9

|

Notes: Figures in parenthesis are the number of judgments.

Table 4 continued

|

2013

|

2014

|

2015

|

2016

|

|

Hoy 37 (1)

Gibson 29 (39)

Norrish 19.3 (12)

Williams 15.6 (5)

Letherbarrow 15.6 (5)

Mahony 15.3 (21)

Haesler 14 (8)

Truss 14 (1)

Knox 13.3 (4)

Payne 12 (1)

Marien 12 (2)

Olsson 11.7 (3)

Levy 11.6 (21)

Murrell 11.4 (9)

Taylor 10.7 (50)

Colefax 10.7 (3)

Marks 9 (1)

King 9 (1)

Walmsley 9 (1)

Neilson 8.6 (24)

Curtis 6 (2)

Elkaim 2.9 (13)

Cogswell 2.8 (41)

Finnane 2.5 (8)

Tupman 2 (2)

Nicholson 2 (1)

Sidis 2 (1)

Berman 0.4 (42)

Sides 0 (1)

|

Whitford 16 (1)

Gibson 15.6 (55)

Haesler 14.4 (8)

Payne 14 (1)

Yehia 13.5 (4)

Lakatos 12 (1)

Olsson 11 (1)

Letherbarrow 11 (2)

Knox 11 (3)

Levy 10.6 (16)

Mahony 10.4 (20)

Hatzistergos 10 (1)

Norrish 7.7 (26)

Williams 6.5 (2)

Taylor 6.2 (53)

Neilson 3.7 (26)

Conlon 3.5 (2)

Colefax 3.5 (2)

Elkaim 2.4 (7)

Cogswell 2 (58)

Sidis 2 (1)

Woods 2 (1)

Curtins 0.6 (31)

Tupman 0.6 (5)

Kearns 0.5 (4)

Berman 0.4 (31)

Finnane 0.1 (8)

|

Payne 25 (3)

Price 24 (1)

Hatzistergos 22.7 (14)

Levy 22.4 (17)

Haesler 21.3 (4)

Gibson 19.8 (51)

Williams 18 (1)

Letherbarrow 16 (1)

Knox 15.6 (7)

Norrish 15.1 (38)

Lerve 14.7 (3)

Olsson 13 (1)

Sidis 10.8 (5)

Mahony 10.5 (32)

Scotting 9 (13)

Syme 9 (1)

Lakatos 8 (4)

Bozic 8 (1)

Conlon 8 (1)

Norton 8 (1)

Elkaim 5.8 (9)

Colefax 5.5 (4)

Neilson 5.2 (69)

Balla 5 (1)

Taylor 4.6 (27)

King 4 (1)

Curtis 3 (6)

Tupman 3 (1)

Kearns 2.1 (15)

Phegan 2 (1)

Berman 1.5 (39)

Cogswell 1.4 (35)

Whitford 1.2 (6)

|

Hatzistergos 15.9 (14)

Haesler 14.8 (4)

Yehia 14.5 (2)

Gibson 13.9 (59)

Lerve 13 (1)

Levy 12.7 (19)

Price 12 (2)

Dicker 11 (12)

Henson 11 (1)

Scotting 10.7 (29)

Mahony 8.0 (39)

Toner 8 (1)

Norrish 7.7 (7)

Montgomery 7.6 (7)

Wass 7 (2)

Delaney 6 (1)

Sidis 5.8 (4)

Taylor 5.4 (25)

Letherbarrow 5 (1)

Whitford 4.5 (2)

Neilson 3.1 (47)

Townsden 3 (1)

Cogswell 2.6 (9)

Elkaim 1.6 (5)

Balla 1.5 (2)

Kearns 1.2 (10)

Berman 0.9 (42)

Colefax 0.5 (2)

Tupman 0 (5)

Curtis 0 (1)

|

|

Weighted average:

10.7

|

7.1

|

10.4

|

7.0

|

Notes: Figures in parenthesis are the number of judgments.

Gibson DCJ stands out as a heavy citer. Her Honour published close to the most judgments in each of 2007–16. Her 165 judgments published in 2014–16 represented 14.48 per cent of the Court’s published judgments in these three years. Gibson DCJ was the most frequent citer of authority in 2008, 2010 and 2012. If I consider only those judges who published at least five judgments per year, Gibson DCJ was the most frequent citer of authority in all but 2015 and 2016, in which she was the third and second most frequent citer respectively on the Court.

Again, if I focus only on those judges who published at least five judgments in a given year, Hatzistergos DCJ, who is a former New South Wales Attorney-General, was the biggest citer of authority in 2015 and 2016. Others who were among the top five citers on the Court on a per judgment basis in multiple years over the period 2007–16 were Levy DCJ (eight times), Norrish DCJ (seven times), Knox DCJ (five times) and Letherbarrow and Williams DCJJ (two times each).[115] At the other end of the spectrum, Berman, Cogswell and Finnane DCJJ, were the Court’s most meagre citers in most years. Their Honours, who each published a large number of judgments most years, generally cited less than two authorities per judgment each year over an extended period. Other judges, who regularly published more than five judgments per year, but cited few authorities per judgment, over multiple years are Ekaim, Neilson, Nicholson and Sidis DCJJ.

Table 5 lists the legal treatises that the District Court cited in published judgments over the period 2005 to 2016. Over this period, the Court cited a total of 110 separate legal treatises. Of these, just 35 received 2 or more citations, 11 received 5 or more citations and 7 received more than 10 citations. The most cited treatises were Ritchie’s Uniform Civil Procedure NSW (48 citations), Tobin and Sexton’s Australian Defamation Law and Practice (21 citations), Fleming’s Law of Torts (18 citations), Brown’s Law of Defamation in Canada (17 citations), Dal Pont’s Law of Costs (16 citations) and Gatley on Libel and Slander (15 citations).

Table 5: Legal treatises cited in District Court cases reported in AustLII/NSW Caselaw

|

Book

|

Number of citations from 2005–2016

|

|---|---|

|

Ritchie’s Uniform Civil Procedure NSW

Australian Defamation Law and Practice (Tobin and Sexton)

Law of Torts (Fleming)

The Law of Defamation in Canada (Brown)

Law of Costs (Dal Pont)

Gatley on Libel and Slander

Uniform Evidence Law (Odgers)

Cross on Evidence (Heydon)

Law of Torts (Balkin and Davis)

Palmer on Bailment

Cheshire and Fifoot’s Law of Contract (Seddon and Ellinghaus)

Statutory Interpretation in Australia (Pearce and Geddes)

Equity Doctrines and Remedies (Meagher, Gummow and Lehane)

Crime and Mental Health Law in NSW (Westmore and Howard)

Criminal Practice and Procedure in New South Wales (Howie and

Johnson)

Sutton’s Insurance Law in Australia

Clerk and Lindsell on Torts

Precedents on Pleading (Bullen and Leake)

The Law of Employment (Macken & Ors)

Aspects of The Law of Defamation in NSW (Tobin)

Professional Liability in Australia (Walmsley, Abadee and Zipser)

The Law Relating to Estoppel by Representation (Bower)

The Criminal Trials Bench Book

A Code of the Law of Actionable Defamation (Bower)

Australian Sentencing Digest (Carter)

Annotated Civil Liability Act 2002 (NSW) (Villa)

Contract Law in Australia (Carter, Peden and Tolhurst)

Estoppel by Conduct and Election (Handley)

Motor Vehicle Law (Lesley and Britts)

The Modern Contract of Guarantee (O’Donovan and Phillips)

Mayne and McGregor on Damages (McGregor)

Expert Evidence (Freckleton, Selby and Blackstone)

Assessment of Damages for Personal Injury (Luntz)

Principles of Insurance Law (Kelly and Ball)

Workers Compensation NSW (Mills)

Precedent in English Law (Cross)

Our Legal System (Gifford)

Salmond on Jurisprudence

Judicial Reasoning and the Doctrine of Precedent in Australia (McAdam and

Pyke)

The System of Law and Courts Governing New South Wales (Morison)

Mareva and Anton Pillar Orders (Biscoe)

The Law of Company Liquidation (McPherson)

Phipson on Evidence

Torts in the Nineties (Mullaney)

The Interpretation of Contracts (Lewis, Sweet and Maxwell)

Commentaries on the Law of England (Blackstone)

Actionable Misrepresentation (Bower)

Rooke and Ward on Sexual Offences

Defamation Law in Australia (George)

Principles of Criminal Law (Bronitt and McSherry)

Criminal Law (Gilles)

Slander and Libel (Folkard)

Criminal Pleading, Evidence and Practice (Archbold)

Family Provision in Australia (de Groot and Nickel)

MacGillivray and Parkington on Insurance Law

Carter on Contract

Butterworth’s Criminal Practice and Procedure NSW

Restitution Law in Australia (Mason and Carter)

The Law of Contract (Greig and Davis)

The Law of Securities (Sykes and Walker)

Return to the Teachings – Hollow Waters Model (Ross)

Law of Torts (Prosser and Keeton)

Duncan and Neill on Defamation

The Law of Defamation in Australia and New Zealand (Gillooly)

Lawyers’ Professional Responsibility (Dal Pont)

Principles of Sentencing (Thomas)

A History of the Criminal Law of England (Stephen)

Law of Torts (Salmond)

Torts, Commentary and Materials (Morison and Sappideen)

Torts: Laws of Australia (Law Book Company)

Professional Liability (Jackson and Powell)

Furzer Crestani’s Assessment Handbook

The Law of Liability Insurance (Derrington and Ashton)

Sentencing Manual (Potas, Judicial Commission of NSW)

Pedestrian Accident Reconstruction (Eubanks)

Keating on Building Contracts

Air Law (Shawcross and Beaumont)

Building and Construction Contracts in Australia (Dorter and Sharkey)

Disputes and Dilemmas in Health Law (Freckleton and Peterson)

The Law Relating to Bills of Exchange in Australia (Riley)

The Law Relating to Bills of Exchange in Australia (Russell and

Edwards)

The Law Relating to Banker and Customer in Australia (Weaver and

Craigie)

Lane’s Commentary on the Australian Constitution (Lane)

A History of English Law (Holdsworth)

Law of Bail: Practice, Procedure and Principles (Donovan)

Criminal Law in New South Wales Volume 1 (Watson and Purnell)

NSW Motor Accidents Practitioners Handbook

Sentencing Bench Book

Reputation and Defamation (McNamara)

Miller’s Australian Competition and Consumer Law Annotated

Taxation of Costs Between Parties (Saddington)

Costs (Solicitor and Client) (Saddington and White)

Wigmore on Evidence

Digest of the Criminal Law (Stephen)

Medico-Legal Evaluation of Hearing Loss (Dobie)

Uncommon Law (Herbert)

Seddon on Deeds (Seddon)

Starkie’s Law on Evidence

The Liability of Employers (Glass, McHugh and Douglas)

Medicine and Surgery for Lawyers (Buzzard, Hughes, Hughes and Well)

Defamation Law (Rolph)

The Restraint of Trade Doctrine (Heydon)

Kerr on Injunctions (Paterson)

Social Media and the Law (George, Allen, Benson, Collins, Mattson, Munsie,

Rubagotti and Stuart)

The Law of Torts in Australia (Trindade, Cane and Lunney)

Fishes and Lightwood’s Law of Mortgage (Tyler)

Institutes of the Laws of England (Cole)

Workers Compensation Practice in NSW (Boulter)

Seminars on Evidence (Glass)

Hatred, Ridicule or Contempt: A Book of Libel Cases (Dean)

|

48

21

18

17

16

15

12

8

7

5

5

4

4

3

3

3

3

3

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

|

Notes: Legal texts/treatises only. In this table each source is only counted once per case, regardless of whether it was cited in multiple paragraphs in that case. Hence, the total citations are less than in the total column for legal texts in Table 2, in which sources are counted more than once if cited in multiple paragraphs. This table does not include non-legal books. Dictionaries, medical dictionaries and legal encyclopedias are not included.

A few observations can be made of the data presented in Table 5. First, among those sources that received multiple citations, there were several ‘local favourites’.[116] These included Ritchie’s Uniform Civil Procedure NSW, Westmore and Howard’s Crime and Mental Health Law in NSW, Howie and Johnson’s Criminal Practice and Procedure in NSW, Tobin’s Aspects of the Law of Defamation in NSW, Villa’s Annotated Civil Liability Act 2002 (NSW) and Mills’ Workers Compensation NSW. Citations to local favourites typically constitute convenience citations, in which the source conveniently summarises the current law in New South Wales. Previous studies of the citation practice of the state supreme courts in both Australia and the United States have also found that such courts like to cite their local favourites.[117]

Second, compared with the appellate courts, the District Court is concerned with a disproportionate number of procedural matters relative to substantive matters. That the Court hears a lot of procedural matters helps explain the Court’s preponderance to cite texts focused on procedure such as Dal Pont’s Law of Costs, Ritchie’s Uniform Civil Procedure NSW and Howie and Johnson’s Criminal Practice and Procedure in NSW. Many of these citations are also convenience citations, summarising the appropriate procedure.

Third, the Court cites a high proportion of modern commentators. Among those sources cited four or more times by the Court are Tobin and Sexton’s Australian Defamation Law and Practice, Fleming’s Law of Torts, Heydon’s Cross on Evidence, Seddon and Ellinghaus’ Cheshire and Fifoot’s Law of Contract and Meagher, Gummow and Lehane’s Equity Doctrines and Remedies. Previous studies have found that the High Court and Federal Court also cite a high proportion of modern commentators.[118] There are two reasons for citing modern commentators. One is convenience. As Merryman puts it: ‘They are an expression of the view that on some questions legal development is cumulative, that progress up to a certain point can be drawn from the decisions, statutes, and administrative practice and accurately restated in summary form’.[119] In a busy trial court, such as the District Court, it is easier to cite these texts than trace the evolution of legal principle through citation to case law. The other is that many of these modern texts have been endorsed in the High Court and Court of Appeal as correctly stating the law and, in this sense, become de facto primary authorities. For example, Cross on Evidence, Fleming’s Law of Torts and Meagher, Gummow and Lehane’s Equity Doctrines and Remedies, were the first, third and seventh most cited books on the state supreme courts over the course of the twentieth century.[120] Fleming’s Law of Torts and Meagher, Gummow and Lehane’s Equity Doctrines and Remedies were also the fourth and thirteenth most cited books respectively by the High Court in the years 1960, 1970, 1980, 1990 and 1996.[121]

Fourth, the subject matter of the cases the Court hears influences the text it cites. Many of the most cited texts are concerned with crime, evidence and procedure, reflecting the fact that almost 60 per cent of the cases that the Court hears are in this area (see Table 1). Also of note is that several of the most cited texts are concerned with defamation or torts more generally. This also reflects subject matter – torts constituted 17 per cent of cases in the sample (see Table 1). This is likely contributed to by the fact that Gibson DCJ is one of the heaviest citers of authority on the Court and that her Honour hears many defamation cases.

In addition to legal treatises, the District Court also cited various non-legal books. One reason given earlier for citing secondary sources, particularly non-legal sources, is to examine the philosophical or scientific basis of legal rules. One would expect citing authorities in order to establish the underpinning ‘legislative facts’ and as a vehicle to explore expert evidence in more detail to be more important given that the Court is commonly concerned with establishing issues of fact against a backdrop of legal principle. The Court cited The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders six times as well as books such as Leonard’s Concise Gray’s Anatomy, Steinberg’s The Hip and its Disorders, Netter’s Atlas of Human Anatomy, Shorter’s A History of Psychiatry, Armstrong and Slaytor’s The Colour of Difference: Journeys in Transracial Adoption and Ballantyne’s Deafness on one occasion each.

A study of the citation practice of United States courts found increasing reference to the Bible in judgments.[122] The Court cited the Bible once in a defamation case involving the Church[123] and also cited Jeffrey’s A Dictionary of Biblical Tradition in English Literature, when exploring the concept of

‘thirty pieces of silver’.[124] Previous studies have found that the courts, albeit infrequently, also cite philosophy.[125] In Cavasinni v Camenzuli[126] Gibson DCJ, when examining the meaning of ‘weasel word’, cites Shakespeare:

What is a ‘weasel word’? This is a word often used in applications to strike out imputations, but never explained, so I have checked its meaning in Wikipedia. The phrase ‘weasel word’, referring to a word which sucks the meaning out of a sentence the way a weasel sucks an egg but leaves the empty shell, is an adaptation of Shakespeare’s metaphor in As You Like It: ‘I can suck melancholy out of a song as a weasel sucks eggs’ (Act II, scene v).[127]

Also of interest in this passage is her Honour’s reference to checking the meaning in Wikipedia. There are six other District Court judgments published on AustLII, five of which are judgments of Gibson DCJ, in which the Court refers to Wikipedia as a source of information.[128] This seems a rather curious practice, given that Wikipedia is recognised as often being inaccurate[129] and that citing Wikipedia in an undergraduate term paper, let alone an academic paper, is generally frowned upon.[130] Citing Wikipedia in the District Court is likely to be a function of time constraints, although, it is submitted, there are better sources to cite.

Table 6 contains a list of citations to legal periodicals in the District Court, along with their Excellence in Research Australia (‘ERA’) 2010 and Australian Business Dean’s Council (‘ABDC’) 2016 rankings. The Court cited 31 legal periodicals in total, of which 10 received multiple citations. The most cited law journal, with eight citations, was the Australian Law Journal. The Australian Law Journal was also the most cited law journal on the High Court in 1999 (the most recent year for which we have data),[131] the Federal Court[132] and state supreme courts,[133] as well as in the Final Reports of the Australian Law Reform Commission.[134] The pre-eminence of the Australian Law Journal as a journal that judges cite, suggested by this study and other studies, is reinforced by two factors. One is that it is a journal judges read.[135] The other is that it is a journal to which judges regularly contribute articles.[136] The latter is related to one of the reasons for citing secondary sources, discussed above, which is to refer to the statements of other judges, writing extra-judicially.

Table 6: Legal periodicals cited in District Court cases reported in AustLII/NSW Caselaw

|

Legal periodicals

|

Number of citations from 2005–2016

|

ABDC 2016 Ranking

|

ERA 2010 ranking

|

|

Australian Law Journal

The Judicial Review

Law Society Journal

Crime and Justice Bulletin (NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and

Research)

UNSW Law Journal

Journal of Contract Law

Melbourne University Law Review

Boston University International Law Journal

Criminal Law Journal

Journal of Law, Information and Science

Australian Civil Liability (Newsletter)

Australian Business Law Review

Australian Property Law Journal

Australian Bar Review

Cambridge Law Journal

Insurance Law Journal

Building and Construction Law Journal

Sydney Law Review

Suffolk University Law Review

Queensland University of Technology Law and Justice Journal

University of Western Australia Law Review

Thurgood Marshall Law Review

Judicial Officer’s Bulletin

Current Legal Problems

Police News

Media and Arts Law Review

Law Quarterly Review

Journal of Judicial Administration

Edinburgh Law Review

Griffith Law Review

Torts Law Journal

|

8

3

3

3

2

2

2

2

2

2

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

|

A

N/R

N/R

N/R

A

A*

A

N/R

N/R

B

N/R

A

B

A

A*

A

N/R

A

B

C

B

N/R

N/R

A

N/R

C

A*

N/R

N/R

C

A

|

B

C

N/R

N/R

A*

A

A*

B

A

N/R

N/R

B

B

C

A*

C

C

A*

C

C

B

C

C

A*

N/R

B

A*

B

B

A*

B

|

Notes: ERA 2010 rankings obtained from the John Lamp search engine, available at http://lamp.infosys.deakin.edu.au/

era/?page=fnamesel10. The ABDC 2016 rankings are available at http://www.abdc.edu.au/pages/abdc-journal-quality-list-2013.html. In both rankings journals are ranked C, B, A or A* with A* denoting the highest quality. N/R means that the legal periodical is not reported in the relevant ranking. In this table each source is only counted once per case, regardless of whether it was cited in multiple paragraphs in that case. Hence, the total citations are less than in the total column for legal periodicals in Table 2, in which sources are counted more than once if cited in multiple paragraphs.

It is interesting to examine the ABDC and ERA rankings of the journals that judges cite. The Australian Law Journal is ranked A in the latest ABDC rankings, but was only ranked B in the ERA 2010 rankings. Of the 10 law journals that received multiple citations, just three (University of New South Wales Law Journal, Journal of Contract Law and Melbourne University Law Review) were A* journals in one of the two rankings (and none were A* in both rankings). Most of the journals that the judges cited multiple times were not ranked in one or both of the rankings or, if ranked, received a relatively low ranking – either a B or C. These results are consistent with the concerns expressed by some judges, discussed above, that the academic law journals that are considered elite by the academy – reflected in the fact they have an A* rating – are not publishing articles that busy trial judges find of use.

An important difference between the District Court, on one hand, and the High Court and state supreme courts, on the other, is that the latter cite the leading Ivy League Law Reviews in the United States – Harvard Law Review, Columbia Law Review and Yale Law Journal – and the leading UK law journals – Law Quarterly Review, Modern Law Review and Cambridge Law Journal – to a much greater degree.[137] The District Court cited each of the Cambridge Law Journal and Law Quarterly Review once and did not cite the others at all. The most likely explanation is that the articles in these journals focus on theoretical and policy developments in the law, which are of use to the appellate courts, but are not of particular relevance to a trial court.

It is also interesting to consider Tables 5 and 6 in light of Friedman et al’s perception of legitimacy.[138] A review of Tables 5 and 6 suggests that most of the frequently cited texts are also likely to be perceived as ‘almost as’ or ‘just as’ legitimate as legal doctrine – they are generally authored by judicial officers or senior barristers with whom the judge may have a professional relationship. In Table 6, at least five of the articles in the Australian Law Journal and all three Judicial Review articles are written by senior judges. Thus, as discussed above, a likely reason for why the Court cites few secondary authorities is that the judges consider only legal authorities are legitimate. Reinforcing this point, when they do cite secondary authorities, the secondary sources that they cite often have the status of de facto primary authority.

In concluding I return to the central reason offered in the introduction for why it is important to study the citation practice of inferior trial courts. Such courts are on the frontline in the application of the law in Australia. If individuals having matters heard in inferior trial courts in Australia – who represent the vast majority of those who have any involvement with the courts – are to understand why decisions are made as they are, it is important to understand how, and why, judges of these courts decide as they do. An analysis of the citation practice in inferior trial courts provides an insight into the application of the common law at the coalface.

At the beginning of this study I conjectured that the institutional context of decision-making in the District Court was likely to throw up several differences in the citation practice of that Court, compared with superior courts. These conjectures have been borne out in the data.

There are five main conclusions from this study which juxtapose the citation practice of a busy inferior trial court with what we know about the citation practices of appellate courts in Australia. The first is that the District Court cites fewer authorities than the state supreme courts or High Court. The second is that hierarchical citations constitute about two thirds of total citations and that hierarchical citations form a higher proportion of total citations than in the state supreme courts. The third main conclusion is that consistency citations represent less than five per cent of total citations, which is much lower than in appellate courts. The fourth conclusion is that coordinate citations are miniscule and much lower than those in appellate courts. Both the second and third conclusion reflect the relatively small number of County Court and District Court cases online, together with authority doubting their precedent value. The fifth conclusion is that citations to secondary sources and, in particular, legal periodicals on the District Court is lower than existing studies suggest is the case in appellate courts. This conclusion likely reflects that most secondary sources, to the extent that they have a law reform flavour, are not well suited to inform decision-making on the District Court. Those secondary sources that the Court cites most tend to be local favourites that typically contain convenient summaries of the law in New South Wales that the Court applies every day.

These findings reflect the impact of the distinctive District Court context, as a busy trial court, on judgment writing and, hence, citation practice, when compared with the superior courts. It seems that almost every year, the foreword to the District Court Annual Review, penned by the Chief Judge, laments an increase in workload and decline in, or lack of, judicial resources.[139] The findings also reflect institutional differences, including difference in case complexity, difference in balance between legal and factual issues, differences in the proportion of procedural and substantive matters that the Court hears, resourcing of the judges and differences in time available to prepare judgments in trial courts vis-à-vis appeal courts.

[*] Professor and Deputy Dean (Academic Resourcing), Monash Business School. I thank Alicia Eng and Tushka Sridharan for research assistance, Lisa Freeman for advice on the reporting practices of the District Court and the anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on an earlier version of this article.

[1] See Jason Bosland and Jonathan Gill, ‘The Principle of Open Justice and the Judicial Duty to Give Public Reasons’ [2014] MelbULawRw 20; (2014) 38 Melbourne University Law Review 482; Luke Beck, ‘The Constitutional Duty to Give Reasons for Judicial Decisions’ [2017] UNSWLawJl 34; (2017) 40 University of New South Wales Law Journal 923; Lord Denning, Freedom under the Law (Stevens & Sons, 1949) 91; Michael Kirby, ‘Reasons for Judgment: “Always Permissible, Usually Desirable and Often Obligatory”’ (1994) 12 Australian Bar Review 121; Martin Shapiro, ‘The Giving Reasons Requirement’ [1992] University of Chicago Legal Forum 179.

[2] David J Walsh, ‘On the Meaning and Pattern of Legal Citations: Evidence from State Wrongful Discharge Precedent Cases’ (1997) 31 Law & Society Review 337, 338.

[3] Lawrence M Friedman et al, ‘State Supreme Courts: A Century of Style and Citation’ (1981) 33 Stanford Law Review 773, 794 (emphasis in original).

[4] John Henry Merryman, ‘The Authority of Authority: What the California Supreme Court Cited in 1950’ (1954) 6 Stanford Law Review 613.

[5] See, eg, Vaughan Black and Nicholas Richter, ‘Did She Mention My Name? Citation of Academic Authority by the Supreme Court of Canada, 1985–1990’ (1993) 16 Dalhousie Law Journal 377; Peter McCormick, ‘Judicial Authority and the Provincial Courts of Appeal: A Statistical Investigation of Citation Practices’ (1994) 22 Manitoba Law Journal 286; Peter McCormick, ‘The Evolution of Coordinate Precedential Authority in Canada: Interprovincial Citations of Judicial Authority, 1922–92’ (1994) 32 Osgoode Hall Law Journal 271; Peter McCormick, ‘Second Thoughts: Supreme Court Citation of Dissents and Separate Concurrences, 1949–1996’ (2002) 81 Canadian Bar Review 369.

[6] See, eg, Mary Anne Bobinski, ‘Citation Sources and the New York Court of Appeals’ (1985) 34 Buffalo Law Review 965; Brett Curry and Banks Miller, ‘Case Citation Patterns in the US Courts of Appeals and the Legal Academy’ (2017) 38 Justice System Journal 164; Charles A Johnson, ‘Citations to Authority in Supreme Court Opinions’ (1985) 7 Law & Policy 509; William H Manz, ‘Citations in Supreme Court Opinions and Briefs: A Comparative Study’ (2002) 94 Law Library Journal 267; William H Manz, ‘The Citation Practices of the New York Court of Appeals, 1850–1993’ (1995) 43 Buffalo Law Review 121; John Henry Merryman, ‘Toward a Theory of Citations: An Empirical Study of the Citation Practice of the California Supreme Court in 1950, 1960 and 1970’ (1978) 50 Southern California Law Review 381; Lee Petherbridge and David L Schwartz, ‘An Empirical Assessment of the Supreme Court’s Use of Legal Scholarship’ (2012) 106 Northwestern University Law Review 995.

[7] See, eg, Rebecca Lefler, ‘A Comparison of Comparison: Use of Foreign Case Law as Persuasive Authority by the United States Supreme Court, the Supreme Court of Canada, and the High Court of Australia’ (2001) 11 Southern California Interdisciplinary Law Journal 165; Karen Schultz, ‘Backdoor Use of Philosophers in Judicial Decision-Making? Antipodean Reflections’ (2016) 25 Griffith Law Review 441; Russell Smyth, ‘Other than “Accepted Sources of Law”? A Quantitative Study of Secondary Source Citations in the High Court’ [1999] UNSWLawJl 40; (1999) 22 University of New South Wales Law Journal 19; Russell Smyth, ‘Academic Writing and the Courts: A Quantitative Study of the Influence of Legal and Non-legal Periodicals in the High Court’ [1998] UTasLawRw 12; (1998) 17 University of Tasmania Law Review 164; Russell Smyth, ‘Citations by Court’ in Tony Blackshield, Michael Coper and George Williams (eds), The Oxford Companion to the High Court of Australia (Oxford University Press, 2001) 98; Paul E von Nessen, ‘The Use of American Precedents by the High Court of Australia, 1901–1987’ [1992] AdelLawRw 8; (1992) 14 Adelaide Law Review 181.

[8] Zoe Rathus, ‘Mapping the Use of Social Science in Australian Courts: The Example of Family Law Children’s Cases’ (2016) 25 Griffith Law Review 352.

[9] See, eg, Russell Smyth, ‘The Authority of Secondary Authority: A Quantitative Study of Secondary Source Citations in the Federal Court’ [2000] GriffLawRw 3; (2000) 9 Griffith Law Review 25; Russell Smyth, ‘Law or Economics? An Empirical Investigation into the Influence of Economics on Australian Courts’ (2000) 28 Australian Business Law Review 5.