|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal Student Series |

SINGAPORE’S ETHNIC INTEGRATION POLICY: THE KEY TO A RACIALLY HARMONIOUS SOCIETY?

HARRISON CHEN[*]

Racial and ethnic segregation are a phenomenon the world over. Singapore has attempted to combat segregation through the housing market to achieve spatial (and hopefully social) integration of minority ethnic groups with an ‘Ethnic Integration Policy’. This paper examines this policy and its advantages and disadvantages. More importantly, this paper considers whether this policy has successfully accomplished the objectives it initially set out to achieve.

I INTRODUCTION

The historical tendency humans have to divide themselves along ethnic and racial lines is a concerning phenomenon that we still see in many contemporary societies.[1] Developing solutions for overcoming racial and ethnic segregation, self-imposed or otherwise, is an important objective, and the Singaporean experience provides an interesting case study on dealing with such divisions. Although there has been significant appreciation of Singapore’s economic achievements in the past five decades, the international media rarely acknowledges the nation’s success in fostering an inclusive and ethnically cohesive society.[2] Despite having an inherently multiracial demographic, Singapore has succeeded in forging a harmonious society in its short history as an independent state. One factor recognised as being integral to this achievement is Singapore’s use of an ethnic residential quota system through its housing market, also known as the Ethnic Integration Policy (‘EIP’).[3] Therefore, a critical analysis of the EIP and an evaluation of its effectiveness and deficiencies provides us with a topical and important area of discussion. Furthermore, Singapore’s success in achieving racial harmony not only makes it a fascinating case study, but also one that we may be able to draw many important lessons from. This essay’s central proposition is that although the EIP has been able to successfully accomplish the objectives it initially set out to achieve, Singapore will need to gradually transition from this state-drive mechanism to an integration policy that is more holistic in its approach and sympathetic in its execution.[4] We begin in Section II by discussing the features of the Singaporean context that initially prompted the need for such a policy, and that later were integral to its effective implementation. Section III will then provide a critical analysis of the EIP, and examine its strengths and flaws, whilst also contextualising the policy amongst the greater framework of ‘integration management’ programmes.[5] Finally, in Section IV, we will assess the continuing relevance of the EIP and propose recommendations to ensure that it evolves into a policy that continues to be effective for contemporary Singaporean society.

II THE SINGAPOREAN CONTEXT

The use of ethnic quotas is certainly not unique to Singapore.[6] However, the exceptional circumstances that led to the city-state’s independence, alongside the initial conditions faced by the newly elected Singaporean government back in 1965, create a case study that is highly interesting and quite remarkable. Therefore, before we delve into a critical analysis of the EIP itself, it is useful to provide a brief background to the Singaporean context that engendered it. In this section we will seek to answer two key questions.

1. What elements of Singapore’s history necessitated the development of a policy like the EIP?

2. What characteristics of the Singaporean context allowed the EIP to be successfully implemented?

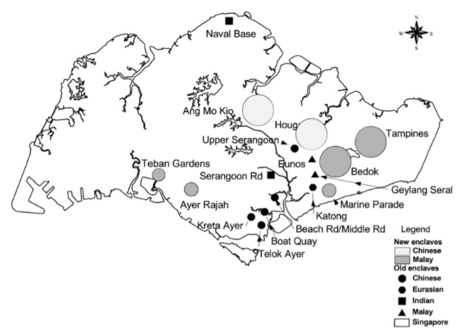

In answering the first question, it is necessary to acknowledge Singapore’s extremely poor initial conditions. Towards the end of the 1950s and at the start of the 1960s, Singapore’s lack of natural resources, political turbulence of self-government and unexpected independence resulted in the nation’s inability to attract long-term investments.[7] During that period, the problems of the newly sovereign nation could really be encapsulated into two mounting concerns. Firstly, the government was faced with a largely immigrant and growing population, and a chronic housing shortage. Measures previously undertaken by the British colonial government in the provision of rental accommodation and town planning had proved wholly inadequate, and by 1959 over 90% of the Singaporean population were living in overcrowded urban slums and squatter settlements lacking access to water and modern sanitation.[8] The second concern was also a legacy of the British colonial rule and ironically a major factor that ultimately led to Singapore’s independence.[9] Colonial planning under British administration had created the existence of ethnic groups living in largely segregated concentrations (as can be seen from the diagram below), which ultimately erupted in the violent race riots of 1964 that resulted in Singapore’s expulsion from the Malaysian Federation and its subsequently unexpected independence.[10]

Ethnic Enclaves before 1989,

Singapore[11]

Ethnic Enclaves before 1989,

Singapore[11]

To deal with these two rising concerns, the government established four key objectives for its housing policies.[12]

1. The Provision of Shelter

2. Home Ownership

3. Community Bonding

4. Building a Vibrant Community

From the objectives above, it is already quite clear how Singapore’s historical context created a necessity for the EIP and furthermore provided the government with a rationale for implementing it.

Moving to the second question, underlying the Singaporean government’s ability to develop its housing policies were the three central pillars listed below.[13]

1. The establishment of Housing and Development Board (‘HDB’) in 1960.

2. The enactment of the Land Acquisition Act 1966 (Singapore).

3. The expansion of the role of the Central Provident Fund (‘CPF’) in 1968.

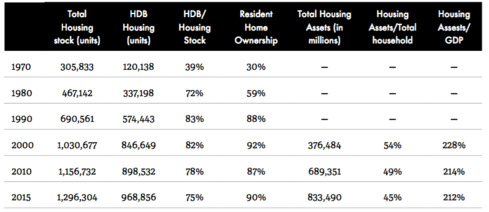

For the purposes of this essay, it would be pointless to undertake a detailed examination into the complexities of these three pillars, as their dominant role in Singapore’s housing sector has already been extensively documented.[14] Instead, we just need to understand what sort of housing system these three pillars were able to collaboratively create for Singapore. The HDB is the key pillar of Singapore’s housing system and over the past five decades has built almost one million public homes, equating to ~73% of Singapore’s total housing stock.[15] An essential precondition for such large-scale provision of public housing was the enactment of the Land Acquisition Act 1966 (Singapore) that empowered the state to legally acquire the necessary land for development by the HDB. Finally, the expansion of the role of CPF to be utilised as a vehicle for housing finance in 1968 contributed significantly to the growth of the mortgage sector and catalysed the increases in homeownership rates in the decades that followed. Today, over 90% of all Singaporean land is state land,[16] and the homeownership rate for the resident population has been around 90% since the early 1990s.[17] In 2018, more than 80% of the resident population lives in a property bought from the HDB.[18] It is explicitly clear then, that public housing is not some residual element in the Singaporean housing market, but rather is the dominant form of housing.[19] Given that the HDB effectively plays the role of landlord, financier and legal provider for residents in public housing, coupled with the serious lack of alternatives to public housing,[20] it is easy to see why a housing policy such as the EIP was able to be so efficiently and effectively implemented on a national scale.[21]

Table 1: Indicators of Housing Stock and Assets[22]

III THE ETHNIC INTEGRATION POLICY

A What is the EIP and how does it work?

Now that we understand how the Singaporean historical context created the need, rationale and foundation for an effective implementation of the EIP, we can start delving into what the EIP actually is, what its key objectives are, and how it works.

As briefly mentioned in Section I, the EIP really works as an ethnic residential quota policy and it was first introduced in 1989 to respond to the finding that major ethnic groups were re-segregating themselves into more homogenous residential areas.[23] The policy essentially enforces a set of upper limits that restricts ethnic proportions at the block and neighbourhood level.[24] Any sale transaction that pushes the ethnic proportion of a particular neighbourhood/block above its respective limit is barred.[25] Let us consider the example of a neighbourhood/block in which the limit for Malays has already been reached to help illustrate how this policy actually functions. In this situation, non-Malay flat owners only have the option of selling their public housing units to other non-Malay buyers, since selling to a Malay buyer would push the proportion of Malays above the policy limit. Interestingly, the way the policy applies to a Malay flat owner in this situation is slightly different. The EIP contains a ‘grandfathering’ element that applies even if a particular ethnic group started above the quota.[26] Essentially what this means is that a Malay flat owner in this scenario would be able to sell to both non-Malay and Malay buyers, since both options would still leave the existing proportions unchanged. In other words, even if the Malay quota were already at or above capacity, selling a public housing unit to a Malay buyer would not change the level of segregation in that specific neighbourhood/block. The general principle underlying this rule is that an ethnic group that has already exceeded its limit should not be able to ‘grow’, but can remain at the same level, for that particular location.[27]

Potential buyers and sellers can check the HDB portal website for the EIP quotas of every specific neighbourhood/block.[28] On the website, the HDB provides monthly updates on neighbourhood/block(s) that are affected by ethnic quotas. Those affected by quotas will then be announced on the first day of every month and these limits will continue to hold until the next month commences.[29] It is already evident then, that the structure of the EIP gives rise to certain logistical issues and that its effect on different ethnicities is also uneven. We will go into more detail about the flaws of the EIP in Part C. Finally, before we can assess whether the EIP has been successful in achieving its objectives, we need to actually outline what these objectives are. Dr Puthucheary who is the Senior Minister of State for Communications, Information and Education in Singapore has stated that there are two main objectives of the EIP.[30]

1. To prevent any particular race from congregating in a location giving rise to ‘enclaves’.

2. To give residents more opportunities to interact with those from other races as they ‘go about their daily lives’.

Now that we understand how the EIP works and what its objectives are, we continue in the next section with an examination of how effective the EIP has been.

B Effectiveness of the Ethnic Integration Policy

Our discussions so far have established that elements of Singapore’s historical background, primarily the formation of the HDB and the extremely high proportion of state-owned land, allowed a policy like the EIP to be swiftly implemented with relatively little resistance. However, it is important to recognise that there is a distinct difference between implementing a policy and having it widely accepted. It is clear from our explanation of the EIP in Part A, that such a residential quota would be seen by the community as highly intrusive.[31] Particularly for a democratic state, albeit a flawed one,[32] creating a policy that intrudes too significantly into an individual’s private life would be considered highly unpopular and most likely face significant backlash. A closer examination of how the policy was implemented and who it continues to effect reveals that the Singaporean government did take the intrusive nature of the policy into consideration, and made attempts to mitigate it. Weder di Mauro in a 2018 Policy Brief noted that the intrusive nature of a residential quota system could be minimised if it were only applied to new housing stock.[33] In Singapore, the EIP was introduced for new housing stock and only partially to the resale market (as a result of the ‘grandfathering’ element explained earlier).[34] This meant that existing housing units were not directly impacted, and in turn that there would be no need to evict or move existing owners out of ethnically concentrated neighbourhood/block(s).[35] Although taking such a gradualist approach would result in the minimal amount of households being affected by the policy, it reduced the impact of the policy on incumbent owners and is arguably a significant reason why the EIP continues to be such a widely accepted and effective policy in Singapore.

Although we have now established that the EIP has been well received, we still need to consider if it has actually been successful in creating a racially integrated and socially harmonious Singaporean society. While the EIP’s gradualist implementation approach limited the initial effects of the quota, there is substantial evidence of the policy’s subsequent success. One example of the EIP’s success can be found in the evenness of residential distributions among ethnic groups. In a paper examining the levels of segregation in Singapore’s largest planning area: Bedok New Town, Sin took a quantitative approach to analysing the impact of the EIP.[36] In his research, Sin considered the Index of Dissimilarity (D), which is the most commonly used index for assessing the evenness of residential distribution amongst different social groups.[37] His findings showed that in comparison to other advanced countries, Singapore’s D-values were remarkably low for all ethnic pairings.[38] Without investigating too deeply into the fairly complex calculations Sin performed, this effectively illustrated that there was a fairly even spread of ethnicities across all neighbourhood/block(s) in Singapore. However, this still does not realistically tell us anything that we do not already know. The practical effect of the EIP was that ethnicities were restricted from forming enclaves, but as Sin and this essay acknowledge, a physical integration does not necessarily equate to a social assimilation.[39] Therefore, the most important question still remains. Is there actual evidence that Singaporeans have become more socially and racially integrated as a result of the EIP? And furthermore, how do we measure this?

One standard that has often been advanced as the ultimate litmus test for social integration is the presence of mixed-race marriages.[40] While the research in this area predominantly examines the significance of intermarriage between white majority and ethnic minority groups, we can still draw upon this research to help us evaluate the effectiveness of the EIP. Although Singapore has an inherently multiracial demographic, it is clear that there exists a distinct Chinese majority in the population. 2017 statistics show us that Singapore is effectively made up of three main ethnic groups: 15% Malay, 7% Indian and 76% Chinese, with the remaining 2% being categorised as ‘Others’.[41] Literature on mixed-race marriages from the USA and Britain support the link between inter-ethnic marriage and social integration, and claim that intermarriage signifies a significant lessening of ‘social distance’ between a minority group and the White majority.[42] Therefore, we can apply this to the Singaporean context by examining the rate of intermarriage between the Malay and Indian minority groups and the Chinese majority. Research from Singapore shows that there has been a gradual but increasing trend of mixed-race marriages, with a recorded 4,928 inter-ethnic marriages in 2010 alone.[43] This represented an increase of 20% from the previous year and is evidence of the very tangible effectiveness of the EIP.[44] As noted above, while physical integration of ethnicities represents a good start, intermarriage is arguably the key to having a successful multicultural society.

We will end Part B, by returning to our discussion on the EIP’s ability to meet its two original objectives. From our discussions above, it is clear that ‘Objective 2’ has been achieved, with the EIP physically providing Singaporeans with more opportunities to interact with those from different ethnicities. However, whether the EIP has been able to accomplish the first objective is more contentious. One unintended consequence of the EIP is that it has resulted in an ‘intensification followed by an extensification’ situation, where the prevention of ethnic enclaves has not really been achieved.[45] In many towns, the EIP has resulted in a lateral expansion of racial enclaves where concentrations of certain ethnicities would build up in a neighbourhood/block before spilling over to the adjacent neighbourhood/block.[46] Nevertheless, despite the continuing preference that certain groups have to re-segregate themselves amongst others of their own ethnicity, the increasing trends of mixed-race marriages do demonstrate that the EIP has been effective to a certain extent. However, it is evident that improvements still need to be made and a discussion of the flaws of the EIP will now follow in Part C.

C Issues with the Ethnic Integration Policy

Arguably the most common criticism of the EIP is that it is too ‘intrusive’ and ‘authoritarian’ in nature for a democracy like Singapore.[47] Furthermore, critics of the policy continue to question the effectiveness of the EIP in changing the inherent human preference we have to re-segregate ourselves amongst others of our own ethnicity. The discussions on the Singaporean government’s gradualist implementation approach, and the evidence of increasing trends of mixed-race marriages are able to answer these criticisms to a certain extent. However, as briefly alluded to in Part A of this section, the very way the EIP operates gives rise to certain practical issues, and further concerns that the policy promotes unequal treatment among different ethnic groups. This essay proposes that the flaws of the EIP can essentially be categorised into four main components, and our discussion of these issues will form the foundation for our recommendations in Section IV.

Issue 1 Inconsistencies between Ethnic Quotas and National Ethnic Percentages[48]

As stated earlier in this essay, Singapore is made up of three main ethnicities: Malay, Indian and Chinese. As a result, the EIP is structured to reflect this, and imposes upper limits on these three ethnic groups at the neighbourhood and block level.[49] However, the issue is that the maximum ethnic limits allowed for neighbourhood/block(s) do not reflect the actual national ethnic percentages. This can be seen from the table below.

Table 2: Comparison of Ethnic Quotas and Percentages

|

|

Chinese

|

Malay

|

Indian & Others

|

|

Percentage of resident population (2016

Census)[50]

|

74.3%

|

13.4%

|

12.3%

|

|

HDB’s maximum ethnic limits for neighbourhood (last revised March

2010)[51]

|

84%

|

22%

|

12%

|

|

HDB’s maximum ethnic limits for block (last revised March

2010)[52]

|

87%

|

25%

|

15%

|

A potential explanation for this inconsistency could be that the HDB’s maximum ethnic limits were last revised in 2010 and as a result the ethnic breakdown of Singapore has changed in the years since. But if we look back at the ethnic percentages from 2010 (74.1% Chinese, 13.4% Malay, 12.5% Indian & Others),[53] they are almost identical to the 2016 statistics and therefore cannot be an explanation for the discrepancy. Although the HDB has not provided an explanation for this, it is interesting to note that the maximum ethnic limits for both the ‘Chinese’ and ‘Malay’ groups are ~10% higher than their actual national proportions. Conversely, the quota afforded to the group ‘Indian & Others’ is only slightly higher than their actual percentage in Singapore’s resident population at the block level, and actually lower at the neighbourhood level. We will propose some possible explanations for what this unequal treatment represents further on in this section.

Issue 2 Mixed-Race Identities

While the increasing trend of mixed-race marriages actually demonstrates the success of the EIP, it has also raised some unexpected concerns, as a result of the way mixed-race children are identified in Singapore. In response to the increases in mixed-race childbirths, a ‘double-barrelled race’ rule was introduced in January 2010.[54] The rule essentially allows a child of mixed-race heritage to take on both the racial identities of their mother and father. To complement this, the EIP was revised to state that ‘only the first race listed of a double-barrelled race would be used’ for the purposes of the residential ethnic quota.[55] For example, for an individual with a race of Malay-Indian, only ‘Malay’ would be accounted for under the quota. This development raises two interesting questions. Firstly, now that mixed-race couples can effectively choose the race of their children, will this create an incentive for couples to select certain races? Although there has not been a significant amount of research done in this area, there is anecdotal evidence from interviews with mixed-race couples, which reveal that parents are actually choosing a race for their child that promises more advantages.[56] Some families have elected to register their child as Indian for example, so that their child will be able to enjoy minority privileges later on in life. Conversely, other families have registered their children as Chinese or Malay to ensure that they would have greater access to housing, with the EIP quotas for these two ethnicities being much higher than the actual national percentages, as noted in the table above. Furthermore, the very existence of this issue leads us to the second question. Is the EIP still truly needed in an increasingly racially ambiguous and cosmopolitan Singapore? We will return to this question in Section IV.

Issue 3 Discriminatory Effects on Malay and Indian Minorities

It has also been argued that the way the EIP operates has discriminatory effects on Malay and Indian minorities. As has been noted throughout this essay, the Chinese are the majority race in Singapore and accordingly also comprise the largest group of potential buyers. We can see from the explanation of how the quota system works in Part A that this creates a much greater difficulty for minority ethnics to sell their properties. Particularly in public housing estates that have already exceeded their Chinese quota limit, this places a discriminatory pressure on Malay and Indian minorities to accept lower selling prices, or else risk a prolonged period without a suitable buyer.[57] Additionally, in a 2012 study, Wong found that Chinese-constrained HDB resale units (only Chinese buyers eligible) were 5-8% more expensive than almost identical Indian or Malay-constrained properties.[58] Furthermore, the study showed that Indian or Malay-constrained units were 3-4% cheaper than the average resale price,[59] again emphasizing the discriminatory impact the EIP has on Singapore’s ethnic minority groups. These findings also highlight that the EIP may potentially be exacerbating the already prevalent existence of income inequality among ethnic groups in Singapore.[60]

Issue 4 Income Inequality and Space Wastage

Historically, there has been a significant disparity in median income between the three major races of Singapore. Data from the HDB in 2000 for example, recorded the mean monthly household incomes of the three major races as S$3948 (Chinese), S$3121 (Indians) and S$2797 (Malays).[61] While the differences in average income between ethnic groups continue to exist, they have become even more physically visible due to the EIP. The combination of price increases in Chinese dominated estates as a result of the EIP, and the relatively lower spending capacity of Indian and Malay minorities has effectively resulted in unfilled Malay and Indian quota leftover flats in more developed and affluent estates such as Bedok New Town.[62] The inefficiency of the situation that the EIP has created, and the resultant waste of land, is especially serious considering that land scarcity is a significant problem that Singapore faces.

Taking a high-level view of the four issues we have discussed, this essay proposes that there is an overarching nexus between the flaws of the EIP and the political environment that created the policy in the first place. If we look at who the EIP favours the most, particularly with reference to Issues 1, 3 and 4, it is apparent that there is an underlying bias against non-Chinese ethnic groups. The mixture of Singapore’s unicameral parliament with the EIP itself has effectively created a Chinese majority in every electorate. This has resulted in the selection of Chinese MPs at proportions consistently greater than the actual proportion of Chinese in the population.[63] Therefore, the discriminatory applications of the EIP on ethnic minorities could potentially be a subtle reflection of the Chinese-bias that serves to further entrench Chinese dominance in Singapore. We should not forget that the EIP was implemented for Singaporeans to appreciate the benefits of racial harmony. If this is the case, it only makes sense that every ethnicity should also be made to bear some of its costs practically.

D The Ethnic Integration Framework

To finish off this section, and to complete our critical analysis of the EIP it is important that we recognise the EIP as simply one part of a greater social and racial integration framework. In the Singaporean context, the effectiveness of the EIP truly resonates when it is situated within the multitude of ‘integration management’ programmes that all pursue the common aim of ‘keeping communities racially diverse’.[64] These ‘integration management’ programmes encompass a diversity of measures including the mixing of small and large flats to ensure a greater mixture of income levels, and the provision of high-quality shared public spaces/services in every neighbourhood.[65] The Singaporean government has also recognized that integration can be achieved in many other facets of life outside of the housing system. Prominent examples of this can be seen through the education and more specifically language policies the government has enacted to further achieve an integrated Singaporean society. The government realised that education was not only a means to train up a workforce, but that education and by extension Singapore’s bilingual language policy[66] could be crucial in creating social stability and a sense of national unity amongst a diverse population.[67]

For a nation that enshrined ‘multiracialism’ into its Constitution, it is undeniable that Singapore has done a significant amount to uphold the fundamental principle upon which it was founded.[68] However, it is also now clear from our analysis in Section III that the EIP has unequal applications for the people it impacts, ultimately contradicting the very objective it seeks to achieve. The success of other policies within the broader integration framework point to fostering a more ‘natural’ form of racial and social harmony, and this is potentially the direction the EIP needs to move towards. Therefore, we will now consider this possibility and other recommendations to ensure the EIP’s continued effectiveness in the contemporary context.

IV CONTINUING ON INTO THE FUTURE

A Is the Ethnic Integration Policy still relevant?

In this section, we will view the EIP through a more normative lens and begin by considering whether the current model of the EIP is still relevant to the contemporary Singaporean context. Ironically, the main arguments supporting the notion that the EIP has become obsolete stem from data that actually confirms the effectiveness of the policy in the first place. We have already alluded to this under our second criticism of the EIP in the previous section, and thus the question remains: Is the EIP necessary for a Singapore that is becoming increasingly racially ambiguous due to the growth in mixed-race marriages?[69] This essay suggests that both theoretically and practically the answer should be no. Theoretically, it would not make sense for a hypothetical Singaporean child who, having an Indian-Chinese father and a Chinese mother, to be officially classified as Indian-Chinese, and therefore be subjected to the HDB’s ‘Indian’ quota and all its restrictions, simply for the goal of preventing racial enclaves. On a practical level, as the next generation of Singaporeans become even more racially ambiguous, the ethnic quotas would become progressively tougher to monitor and enforce. Nonetheless, we need to balance this perspective with the opposing argument that the human tendency to re-segregate cannot be overcome, and that removing the EIP would eventually return Singapore to a state of racial unrest not seen since its expulsion from the Malaysian federation.[70] The international context provides ample evidence of this and many of the proponents of the EIP point to the experience of segregation faced by African Americans in the US and Muslims in France to argue against abolishing the policy.[71] Therefore, we have run into a problem, we need the EIP and what it offers, but not in the form that it currently presents itself. However, perhaps we are asking the wrong question here. Perhaps the real question we should be asking is not whether the EIP continues to remain relevant, but rather, what sort of society do the Singaporeans of today actually want? As opposed to the US and to a certain extent France, Singaporeans have (at least historically) accepted much higher levels of government intervention for the collective, public good.[72] Nevertheless, with the rise of a new Singaporean generation that has not lived through the ethnic conflict of its predecessors, this essay proposes that there needs to be a shift away from the current EIP’s top-down approach to a policy that is more sympathetic in its execution.[73] Thus, in the final part of this essay, we will propose recommendations for how a holistic contemporary policy could be created.

B Recommendations for a Contemporary Ethnic Integration Policy

The flaws of the EIP ultimately show us that in many ways the policy has succeeded in creating a shallow form of racial harmony, and an argument could be made that the policy has simply helped cultivate compliant citizens. In particular, our discussions about the unintended ‘intensification and extensification’ scenario that the EIP has resulted in demonstrate the need for a policy that has a stronger ability to directly impact upon human behaviour. It is worth reiterating here that policy is never implemented in a social vacuum.[74] Even if the spatial manifestation of racial segregation is altered, the hidden social processes involved remain hard to influence.[75] In other words, and as has been noted throughout this essay, simple spatial integration does not necessarily lead to social integration and understanding.[76] Therefore, this essay proposes that what needs to be focused on instead is the ‘bridging of social capital’ between communities, and championing the use of common spaces.[77] This means having neighbourhood events, and encouraging community participation between people of different ethnicities, rather than a strict focus on enforcing housing quotas.[78] Reassuringly, it does seem that the Singaporean government is moving in the right direction, with funding of high-quality shared public spaces/services in every neighbourhood being provided by the aforementioned ‘integration management’ programmes.[79] Moreover, the existence of Singaporean innovations such as the ‘void deck’ in HDB housing estates will continue to push the nation towards a more inherent state of ethnic harmony.[80] This is not to say however, that the EIP was not effective. Rather, it has simply become out-dated, and with the increasing trend of mixed-race marriages and rising income inequality between ethnicities, there is the need to gradually transition from this state-driven mechanism to a policy that is able to foster a more ‘natural’ sense of racial harmony. If Singapore can succeed in creating a society that is intrinsically ethnically integrated, then the necessity for such a state-driven EIP will no longer exist, and the objectives of social and ethnic integration will be ingrained into the very ethos of Singaporean society itself.

V CONCLUSION

Singapore’s Deputy PM Tharman Shanmugaratnam has described the EIP as arguably the ‘most intrusive policy in Singapore’, but also the one that ‘has turned out to be the most important’.[81] The findings from this essay reflect this sentiment, and it is clear that the EIP has been and continues to be effective in achieving the original objectives it was intended to meet. However, our findings also demonstrate that these original objectives and furthermore the EIP itself have become out-dated and no longer sufficient for a contemporary Singaporean society. While the physical mixing of different ethnicities throughout the housing system has helped to foster community bonding and encourage racial harmony to a certain extent, the time has come for Singaporeans to aspire for a more innate form of EIP. In other words, Singapore needs to recognise that genuine ethnic integration cannot be found in residential blocks or neighbourhoods, but rather can only truly be found in the heart of all its citizens.

[*] BCom (Distinction), LLB. This paper was first submitted as the final assessment for LAWS3115: People, Land and Community at the University of New South Wales. I would like to give my utmost thanks to Associate Professor Cathy Sherry BA, LLB (Hons), PhD for her advice and encouragement, and to my father Harry Suhariyanto Chen BScEe, MCompSci for providing me with the inspiration for the subject of this paper. All errors are my own

[1] Ruchika Tulshyan, Singapore’s Social Experiment Key to Economic Success (1 June 2015) Forbes <https://www.forbes.com/sites/ruchikatulshyan/2015/06/01/singapores-social-experiment-key-to-economic-success/#25164b166fd0>.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Phang Sock Yong and Matthias Helble, Housing Policies in Singapore (The Housing Challenge in Emerging Asia, 2016) 197.

[4] Chih Hoong Sin, ‘The Quest for a Balanced Ethnic Mix: Singapore’s Ethnic Quota Policy Examined’ (2002) 39(8) Urban Studies 1347.

[5] Ibid 1348.

[6] In Europe, many settlement policies place limits on where newly arrived immigrants can settle, mostly in an effort to avoid the formation of enclaves: see Maisy Wong, ‘Estimating the Impact of the Ethnic Housing Quotas in Singapore’ (2012) UPenn Real Estate Department Working Paper 2, 8.

[7] Yong and Helble, above n 3, 177.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Beatrice Weder di Mauro, ‘Building a Cohesive Society: The Case of Singapore’s Housing Policies’ (2018) 128 Centre for International Governance Innovation 2.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Loo Lee Sim, Shi Ming Yi and Sun Sheng Han, ‘Public Housing and ethnic integration in Singapore’ (2003) 27(2) Habitat International 296.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Yong and Helble, above n 3, 177-178.

[14] Ibid 182.

[15] Weder di Mauro, above n 9, 3.

[16] Yong and Helble, above n 3, 180.

[17] Weder di Mauro, above n 9, 4.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Chih Hoong Sin, ‘The Quest for a Balanced Ethnic Mix: Singapore’s Ethnic Quota Policy Examined’ (2002) 39(8) Urban Studies 1349.

[20] Ibid 1353.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Weder di Mauro, above n 9, 4.

[23] Ibid 5.

[24] Wong, above n 6, 2.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Weder di Mauro, above n 9, 6.

[27] Hoong Sin, ‘The Quest for a Balanced Ethnic Mix’, above n 19, 1353.

[28] Singapore Government, Ethnic Integration Policy and SPR Quota (29 December 2017) Housing and Development Board < https://www.hdb.gov.sg/cs/infoweb/residential/buying-a-flat/resale/ethnic-integration-policy-and-spr-quota>.

[29] Hoong Sin, ‘The Quest for a Balanced Ethnic Mix’, above n 19, 1363.

[30] Kelly Ng, The policies that shaped a multiracial nation (10 August 2017) Today <https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/policies-shaped-multiracial-nation>.

[31] Weder di Mauro, above n 9, 6.

[32] Raymond Tham, Singapore improves marginally in EIU’s Democracy Index (22 January 2016) Today < https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/singapore-improves-marginally-eius-democracy-index?fbclid=IwAR2mjUdQFqMWlVx3tqrtHhe-CWh4CQDjuJ_AMnznIR9vmUYgz90BrRsjNFs>.

[33] Weder di Mauro, above n 9, 6.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Chih Hoong Sin, ‘Segregation and Marginalization within Public Housing: The Disadvantaged in Bedok New Town, Singapore’ (2002) 17 Housing Studies 267-288.

[37] Ibid 274.

[38] Weder di Mauro, above n 9, 6.

[39] Hoong Sin, ‘Segregation and Marginalization within Public Housing’ (2002), above n 36, 274.

[40] Miri Song, ‘Is Intermarriage a Good Indicator of Integration?’ (2009) 35(2) Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 331.

[41] Weder di Mauro, above n 9, 1.

[42] Song, above n 40, 331-348.

[43] Lisa Li, Race Issues in Singapore: Is the HDB Ethnic Quota Becoming a Farce? (17 February 2011) The Online Citizen <www.theonlinecitizen.com/ 2011/02/17/race-issues-in-singapore-is-the- hdb-ethnic-quota-becoming-a-farce/>.

[44] Ibid.

[45] Hoong Sin, ‘The Quest for a Balanced Ethnic Mix’, above n 19, 1368.

[46] Ibid.

[47] Tulshyan, above n 1.

[48] Weder di Mauro, above n 9, 5-6.

[49] Noting that ‘Indians’ are categorized as ‘Indian and Others’, with ‘Others’ comprised mainly of Europeans and Eurasians.

[53] Ibid.

[54] Ibid.

[55] Ibid.

[56] Dew M. Chaiyanara, The realities of raising mixed race kids in Singapore (2017) The Asian Parent <https://sg.theasianparent.com/raising- mixed-race-children-singapore/>.

[57] Hoong Sin, ‘The Quest for a Balanced Ethnic Mix’, above n 19, 1363.

[58] Wong, above n 6, 4.

[59] Ibid.

[60] Hoong Sin, ‘The Quest for a Balanced Ethnic Mix’, above n 19, 1369.

[61] Ibid.

[62] B. Zareen, Is the HDB Ethnic Integration Policy and ethnic quota still relevant? (2018) 99.co <https://blogstaging.99.co/blog/singapore/ethnic-integration-policy/>.

[63] Stephanie Ho, History of general elections in Singapore (1 September 2014) National Library Board <http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/infopedia/articles/SIP_549_2004-12-28.html> .

[64] Hoong Sin, ‘The Quest for a Balanced Ethnic Mix’, above n 19, 1348.

[65] Weder di Mauro, above n 9, 6.

[66] Yunita Ong, Lee Kuan Yew’s Legacy for Singapore: A Language Policy for a GLobalised World (23 March 2015) Forbes < https://www.forbes.com/sites/yunitaong/2015/03/23/lee-kuan-yews-legacy-for-singapore-a-language-policy-for-a-globalized-world/#5960cb9a3ef9>.

[67] Ng, above n 30.

[68] TodayOnline, In Full: PM Lee on race, multiracialism and Singapore’s place in the world (29 September 2017) TODAY < https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/full-pm-lees-speech-race-multiracialism-and-singapores-place-world>.

[69] Li, above n 43.

[70] B. Zareen, HDB’s Ethnic Integration Policy and Racial Quotas: Are they still necessary? (2016) 99.co <https://blogstaging.99.co/blog/singapore/ethnic-integration-policy/>.

[71] Weder di Mauro, above n 9, 6.

[72] Bryan S. Turner and Kamaludeen Mohamed Nasir, ‘Governing as gardening: reflections on soft authoritarianism in Singapore’ (2013) 17(3) Citizenship Studies Journal 339-352.

[73] Hoong Sin, ‘The Quest for a Balanced Ethnic Mix’, above n 19, 1372.

[74] Ibid.

[75] Ibid.

[76] Hoong Sin, ‘Segregation and Marginalization within Public Housing’ (2002), above n 36, 274.

[77] Zareen, Is the HDB Ethnic Integration Policy and ethnic quota still relevant, above n 62.

[78] Ibid.

[79] Weder di Mauro, above n 9, 6.

[80] Jane M. Jacobs et al, ‘Singapore’s Void Decks’ (2014) Public Space in Urban Asia 80-89.

[81] Yong and Helble, above n 3, 197.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/UNSWLawJlStuS/2019/2.html