Journal of Law, Information and Science

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Journal of Law, Information and Science |

|

LYNLEY HOCKING[*]

The Legislation System Project (LSP) is an information systems development project designed to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the legislation production process by providing a computerised drafting environment, document tracking and the automatic consolidation of amendments. This paper discusses the implementation of the system in relation to the legislation production process and concludes that, while the system may have a great impact on the drafting of legislation, it is unlikely to have a major direct substantive impact on the broader legislation production process.

A parliamentary system created now would probably be quite different to ones created last century because the technology on which the system could be based is quite different. Procedures for producing legislation that utilise computerised information technology could theoretically be quite different from ones that do not. Yet would the implementation of a computerised information system greatly affect existing procedures for producing legislation? The production of legislation is the focus for a major systems development project in the Tasmanian State Service. The Legislation System Project (LSP) aims to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the legislation production process as it occurs outside parliament. It plans to do so by providing drafters with computerised tools for legislation, a document tracking system and automatic consolidation of amendments to legislation. This paper outlines the impetus and goals of the system and predicts the probable impact of the system on the legislative production process. Much of the information used in this paper is derived from documents produced by the systems development team or discussions with people involved in the project and their assistance is gratefully acknowledged.

This paper describes such a systems development project and discusses the implications of such computerisation for the process of producing legislation. Most literature on computerisation and government has focused on either the effect of IT on democracy generally or on the role that government should play in either mitigating the negative effects of information technology or fostering the positive ones. There is very little discussion about the effect of new information technologies on the process of producing legislation and the implications this could have on the workings of parliament.

There is very little literature on the implications of IT on the working processes of a core part of a government's activities, the production of legislation. Voermans and Verharen [1] investigated the possibility of using knowledge-based systems as aids for drafting legislation but did not look at the actual processes of producing legislation and the effect of the proposed technology on it. Chartrand and Ketcham[2] looked at the opportunities for using information resources and advanced technologies in the US congress but focused on the application of computerised tools to aid the consideration of legislation and information conveyance rather than the possible consequences of using the technology. Snellen and Schokker [3] discussed the interaction between the creation of legislation and new information systems and the application of the law enabled by new information systems, but also did not focus on the effect of information technology (IT) on the production of legislation. This paper builds on their work.

The following section introduces this case study before relevant issues from the IT literature are discussed. The paper will illustrate the constraints political processes place on the development of technological systems as well as the constraints technology places on the political processes.

Tasmania is the smallest of the seven states of Australia, with a population of just over half a million. The Australian state governments broadly have the same functions as the Canadian provinces and operate according to the general principles of the Westminster parliamentary system. In Tasmania there are two houses of parliament: the House of Assembly, where the governing and opposition parties sit, and a house of review, called the Legislative Council. Although this case study is limited to an isolated example, it has implications for the legislation production processes of any government and so should be of interest to others involved in information systems development in the public sector or the production of legislation anywhere.

The information has been derived from a longitudinal case study of the systems development project. The next section outlines the process of producing legislation in further detail while subsection 2 describes the pressures for increasing its efficiency and effectiveness. Subsection 3 describes the Legislation System Project.

The production of legislation is a highly complex and iterative process in Tasmania. Legislation includes acts, which have been passed by both houses of parliament and which have received Royal Assent, bills, which are acts being debated by the houses of parliament, and drafts, which is the term for legislation before it reaches the House of Assembly.

As in most states of Australia, legislation is written by lawyers who specialise in the drafting of legislation, called Parliamentary Counsel or, less formally, drafters. Legislation is generally initiated by members of the governing party, usually through Cabinet and is further developed by consultations between the agency responsible for the area of policy covered by the legislation and the Office of Parliamentary Counsel (OPC) before it is reviewed by the Legislative Review Committee, printed by the government printing office and debated in Parliament.

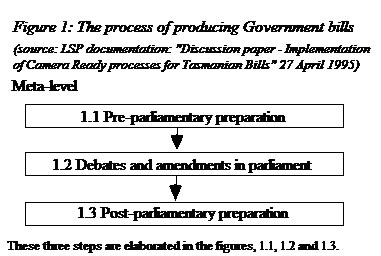

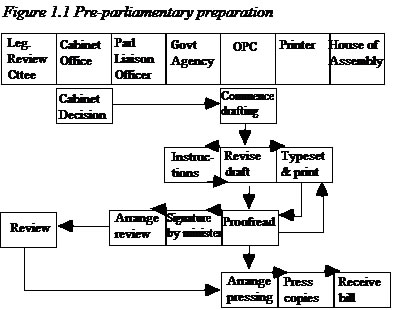

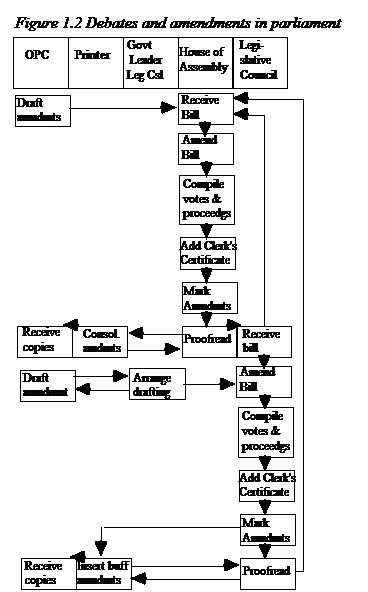

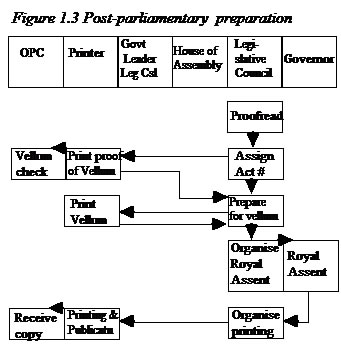

Amendments made on the floor of either house of parliament also must be included in the legislation. Parliamentary counsel are sometimes called upon to draft amendments to legislation on behalf of individual members of Parliament, but otherwise, the OPC loses control over the documents it produces once they are passed onto the Parliamentary Liaison Officer and the Government Printing Office. Figure 1, 1.1, 1.2 and 1.3 illustrate the process of producing such legislation through different governmental bodies before the implementation of computerised information systems. The process is only slightly different for private members bills.

Such diagrams outlining the flow of legislation from its initiation until receiving Royal Assent were produced by the LSP team and are believed to be part of the first thorough review of the process since it was initiated last century. This project is currently under development and has already produced some changes in the legislative production process, as is discussed in section 2.4.

The business case for the LSP identified two critical issues associated with the production and availability of legislation in Tasmania:

• the throughput of the OPC was considered inadequate to meet the increased demand for new or amended legislation and;

• the lack of consolidated legislation was impairing access to the law, increasing the costs of business and government and reducing the effectiveness and standing of the law and Parliament.

There has been an increasing demand for legislation for a number of reasons. Statute law has been used increasingly instead of common law in Australia. There have been large scale reform programs at both the state and national level and also pressures to reform existing subordinate legislation. These trends were intensified over the last few years by the presence of a majority government in parliament. As the governing party had the majority of seats in the house, government initiated legislation was not debated to the same degree in parliament and the throughput of parliament increased.

The increased demand for legislation also reflects the growing complexity of the law. The LSP business case document states,

This increased demand is not simply related to the quantity of legislation but also reflects an increase in the complexity of the drafting task as substantial policy issues with important legal and community ramifications are confronted. In addition, the requirement to respond to requests for amendments from the Parliament further increases this load. Such amendments must be given a high priority as inadequate drafting could result in serious unintended consequences in complex legislation.

The capacity of Parliament to process legislation has outstripped the ability of the existing drafting process to keep pace.

The legislation produced includes new legislation, called principal acts, and amendment acts. These amendment acts have generally not been consolidated into the principal acts and anyone wishing to use acts which have since been amended must manually include these updates. There have been three major periodic consolidations of Tasmanian legislation, in 1902, 1936 and 1959. In 1978 a rolling reprint scheme was introduced but this fell into disuse due to lack of resources including funds, time and personnel qualified to manually consolidate and verify the legislation.

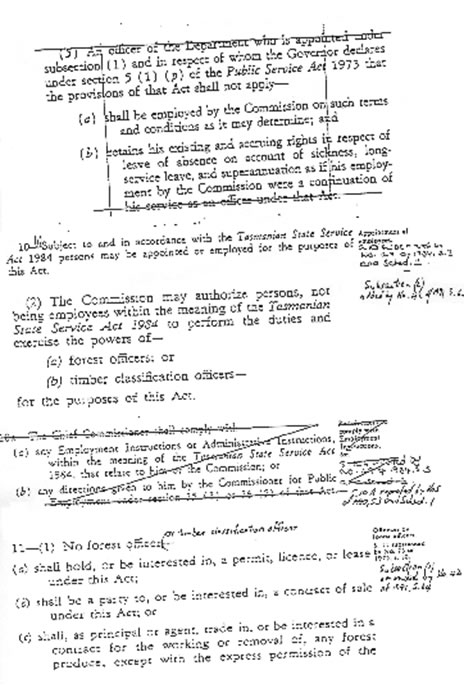

The result has been a cumbersome statute book that is difficult to understand and apply. For example, the Racing and Gaming Act was last reprinted in 1974 and by 1994 had been the subject of 39 amendment acts resulting in over 300 separate amendments which had to be manually incorporated into the principal act. Acts are purchased with a disclaimer to the effect that the government printer did not accept any responsibility for the accuracy of its products. Incorporating these amendments into the principal act was time consuming, prone to error and directly increased the costs of obtaining legal advice or using legislation. Additionally, the manually consolidated versions of the legislation, termed 'pasteups', were cumbersome, even if they were correct, as illustrated in figure 2.

Figure 2: An example of a "pasted up" page of consolidated legislation

(Source: Office of Parliamentary Counsel)

Significant amounts of time and effort are required to interpret the law from such pasteups and mistakes resulting from this interpretation has impinged on the effectiveness of the judicial courts. In one case, the judge and the lawyers from both parties were all working from pasted up versions of an act, each of which was different[4]. The case was delayed until the actual state of the law could be determined. The professional body of lawyers in the state, the Law Society, has expressed concern over the state of Tasmanian legislation and its implications for the Tasmanian legal system.

There were also a number of social costs associated with the lack of consolidated legislation which promoted the LSP. Law based on unconsolidated statutes is complex and requires legal expertise to interpret, imposing unnecessary financial burdens on the community. The poor state of the statute book impacted on the effectiveness of the law, as well as the effectiveness and efficiency of the courts. It also impinged on the effectiveness of parliament, with members of both houses expressing concern about the difficulty of interpreting the legislation they were to debate.

One obvious solution to these problems was to simply increase the number of drafters and support staff, but this is problematic. The specialised nature of the work makes it difficult to attract suitably experienced drafters and there is a nationwide shortage of expertise in this area. In 1994 the OPC obtained the funds to employ another experienced drafter but has not been able to. Training new drafters is not a solution in the short to medium term as training a drafter takes many years and there is a high turnover in the early years as new staff decide whether they wish to make a career in a such a specialised area.

Very little computerised technology is used to aid the production of legislation in Tasmania, and advances in information technologies have suggested solutions to the identified problems. The business case document states:

The OPC has not benefited from improvements in information systems which have increased productivity in other areas of Government activity. Although at its core, drafting is essentially an intellectual and creative task, the process of producing legislation involves many stages which could be significantly improved by automation and access to better information systems.

The catalyst for the LSP was the introduction of a new printing facilities in the government printing office. Drafts that had been carefully verified by the OPC were submitted electronically to the printing office where they were given a new format. In some cases the content of the proposed bill was also changed by accident. An evaluation of the problem identified several surrounding problem areas, which have also become the focus of the LSP.

The LSP aims to provide the following services:

• A legislation drafting and consolidation system within the OPC;

• A legislation database controlled and maintained by the OPC;

• A communications network that provides access to the Bill drafting and consolidation system, and the legislation database (Business Requirement Document pp 11-12)

Most other state jurisdictions use document management systems but, while the State and the Federal government must cope with the problem of consolidating legislation, this is the first time automatic consolidation has been attempted. Many jurisdictions, such as some states in the USA, do not have the problem of automatic consolidation as each amending act repeals the principal act and replaces it with an entirely new one. The LSP team believed that in Tasmania this would require a substantial changes in parliamentary practices and this was outside the brief of the project. There was also the concern that there would be an increased tendency to rework existing provisions which were otherwise satisfactory, impinging on the stableness of the statute books.

The Tasmanian OPC is the most under-resourced in Australia and the standard of the statute book has consequently suffered. The Queensland OPC, for example, has 25 drafters and 25 support staff and Tasmania only has 7 drafters and 7 support staff but has to cover similar areas of law. It is the poor state of the statute book which has prompted the push for automatic consolidation.

Presently the project is in the detailed design stage. The system employs the standard generalised mark-up language (SGML), a technical standard for textual data, to define the structure of the legislation for both storing the information in a textual database and for the purposes of automatic consolidation. An SGML editor is being customised as a suitable drafting environment with close consultation with the drafters and the workflow processes surrounding the new technological system have been evaluated and are under review.

The project plan includes a staged implementation policy over eighteen months and several of these stages have already occurred. The most recent of these stages is the implementation of processes for producing camera ready versions of bills and statutory rules.

There have been and are predicted to be, some minor changes in the movement of acts through parliament as well as a general increase in efficiency as the bureaucracy is able to keep pace with the demands of the executive government. Already the OPC's production of "camera ready" legislation is reducing the role of the government printer and is increasing the role of the OPC over its formal area of responsibility. While previously the legislation was typeset by the government printer, then proofread again by the OPC, the proposed bills and statutory regulations are now being produced in a camera-ready format, then only copied by the printer. The OPC is also gaining greater control over parliamentary amendments. Amendments made by politicians on the floor of the parliaments and passed are forwarded to the OPC to be included in the bill. Previously such amendments were forwarded to the government printer.

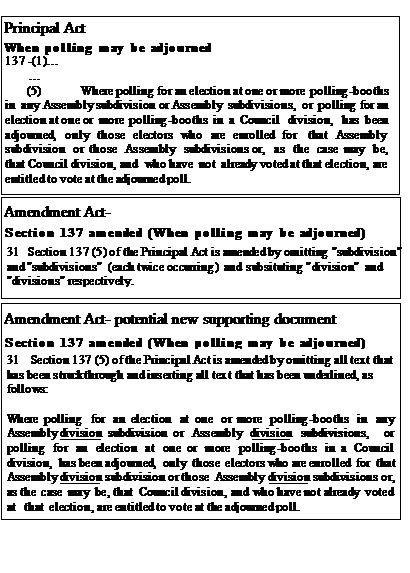

Figure 3: "Insert/Omit" and "Strikethrough/Underline" amendments

(Source: LSP documentation, 16 December 1995)

The LSP could change the format of bills presented to parliament. At the moment proposed amendments to principal acts are given to parliament in an "insert/omit" format, but this could feasibly change to a "strike-through/underline style", as is illustrated in figure 3. Such a change in format is considered to be a possible benefit of the LSP, but it is not being considered in depth until a later stage of the project. To a degree, this is because there are many other tasks that presently take priority but it also reflects a general reluctance to disturb the existing parliamentary arrangements. Strikethrough/underline documents shall perhaps be used as supporting documents to aid interpretation.

However, the LSP has coincided with some more minor formatting changes to legislation, such as the layout of pages and the schedule of provisions. The management of the OPC had previously reviewed the format of legislation, but had only implemented some changes. With the introduction of the camera-ready processes, other formatting changes have been implemented. While the project did not initiate the consideration of such changes, it induced their implementation.

Legally, the consolidation of legislation under the LSP should be covered by the Acts Interpretations Act 1931. This act gives the OPC the power the produce consolidated versions of acts and correct minor errors, such as some grammar and spelling mistakes. Conceptually the automatic consolidation of acts is no different from the manual task of consolidation but the required activities are not adequately covered by the existing legislation. Hence the Acts Interpretation Act is currently being reviewed.

The production of legislation can be divided into two areas: the broad legislation production process, including the houses of parliament and other government agencies as well as the Office of Parliamentary Counsel; and the drafting of legislation within the Office of Parliamentary Counsel. The impact of the LSP on the OPC is expected to be significant.

Due to the likely impact of the new system on the Office of Parliamentary Counsel, the project has involved much interaction between the OPC and the systems developers. The implementation of the system should impact on the office in two main ways:

• the drafting environment and;

• the progress of drafts through the office and the roles of the support staff.

The creation of an improved drafting environment utilising computerised information systems is considered to be one of the most important areas of the LSP by the systems developers and users. The other important aim of the system is to provide automatic consolidation so the drafting environment must be able to support it. Hence there will be some changes in the way drafters write the legislation, the main change being that they will utilise computers when they write. Presently they hand-write drafts which are typed out by administrative staff and amendments to the draft involve constant iterations between the drafter and the administrative staff. With the implementation of the LSP, it is expected that the drafters will input much of their own work directly into the computerised databases of legislation. The system will provide facilities for automatic cross-referencing of acts or sections, automatic numbering of parts and sections in the legislation and the automatic creation of tables of provisions. Such tasks have been a time-consuming area of work for the administrative staff of the OPC and, though this has recently improved with the greater utilisation of word processing facilities, the automation of such tasks are seen to be advantages of the LSP.

The fact that drafters will be writing directly onto the computer will greatly change the flow of work around the office and the roles of the administrative staff especially the typists. Management has emphasised that the LSP will not result in redundancies for any OPC staff but will promote changes in the roles that the staff play. The administrative staff may, for example, be responsible for preparing the drafter's work for automatic consolidation. Such issues are being addressed as part of the detailed design process and the successful management of such changes are viewed as one of the critical success factors of the project.

Information technology has been predicted to induce great organisational changes but, while the LSP will promote changes in and around the OPC, changes directly resulting from the system on the broader parliamentary procedures are expected to be minimal.

There has been a growing awareness in the information technology (IT) literature on the organisational change issues surrounding the implementation of information technology. Such literature has focused on both the implications of organisational, or non-technical issues on the development and implementation of technical systems, but also on the organisational changes resulting from the implementation of information technology. In much the same way that cars were once considered horseless carriages, information technology has often been used to simply automate existing processes and work roles, with word processors being used as glorified typewriters. There has been a recognition that such an approach does not make effective use of the technology and so some IT literature has come to focus on the effective utilisation of technologies by transforming organisations[5].

This trend has perhaps peaked in literature on business process re-engineering (BPR). The aim of writers in this area, such as Hammer and Davenport

[6-9], has been to reevaluate existing organisational processes and to redesign them utilising advanced information technologies to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of these processes. A BPR exercise focusing on the process of producing legislation a la Hammer or Davenport would try to redesign the process without considering the roles played by various bodies and outside the government, the focus being on producing legislation effectively. Such an approach may be a useful way for considering improvements to enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of many organisational processes, but its application in the process of producing legislation flounders on two issues.

The first is the implementability of such changes, is an issue to which much BPR literature has been turning recently. As Davenport[9] has acknowledged, a 'blank sheet of paper' approach to designing change usually relies on a 'blank cheque' for implementation. Yet still much of the literature in the area defines problems associated with BPR as implementation issues, rather than as a problem with BPR itself[10]. Hammer, perhaps the best-known writer in this area, has acknowledged that as many as 70% of BPR projects fail due implementation problems, such as "a lack of top management commitment".

This reflects much of the literature in strategic planning and policy planning, which views the implementation of changes involved as a separate activity governed by the plans or policies defined earlier. There has been a general recognition that such activities are not sequential, and involve the management of emergent as well as planned factors[11]. As Minzberg stated, strategy formulation "...walks on two feet; one deliberate, the other emergent..." [12]. Such an approach has also been reflected in the literature on policy implementation[13] and the literature on the management change[11]. Craig and Yetton[10] make a similar point when reviewing the literature on BPR by suggesting that it is through the implementation of BPR that strategic options will emerge; that is, such activities unfold in a contingent or emergent fashion. A contingent approach to change is recommended for two main reasons. The first is that change generally occurs in a dynamic context.

The second reason for a contingent approach to change is also the second reason why the application of BPR in the process of producing legislation would probably falter. Change can involve alterations in power relationships in and between organisations and the planning of such changes implicitly involves the attainment of some kind of consensus (or cohesion) as to what these changes involve. Debates surrounding the process of producing legislation are likely to become issues for formal political debate in parliament and in the community. Most organisational change efforts are concerned with the achievement of consensus, yet technological change requires such consensus in order to begin[14]. In other words, such debates are likely to adversely affect the outcome of any related information systems development project according to the measures of success used in this area. The detailed design process and programming cannot commence without a reasonable degree of certainty as to the goals and broad content of the changes. The use of prototyping can be used in such a situation, but generally increases the resources and time required for the project.

There have been predictions that information technology will greatly change the internal workings of government. Brussard [15], for example, maintained that the structure of a government's public administration is implicitly dependent on the information technologies available. Therefore, information technologies will influence public sector organisations and their relationship with society as a whole. However, the executive branch of government is lagging behind almost all other social institutions in installing new technologies [16]. Abramson et al [Ibid] suggest this is because the implementation of new technologies can subtly alter the balance of power between government players and the subsequent debates stifle the development of technological systems.

The process of producing legislation is broadly defined in parliamentary standing orders and is deeply embedded in parliamentary and bureaucratic institutions. Business process re-engineering (BPR) projects aim to re-examine the role of institutions in such processes [7], but in this case it is not a practical option to implement many of the changes such an examination would produce. Any alteration to workings of parliament especially could be interpreted as a threat to the existing balance of power between the different political groups in parliament and the resulting debate would probably be significant and lengthy. Any BPR exercise is likely to challenge existing power bases, but in this case the issues are magnified in that the status quo is the formal system of government. Hence, the LSP has necessarily avoided changing or challenging the workings of parliament.

This strategy reflects Kraemer's argument that information systems do not induce reform in organisations, but tend to reinforce existing organisational arrangements and power distributions and Brinckman's belief that advanced information technology is rarely used for organisational innovation[14, 17]. Those responsible for the LSP seem to implicitly reflect Kraemer's assertion:

Although computing can in theory lead to new administrative structures, in practice, it doesn't, it can't, and it probably shouldn't. And each time such structures have been attempted in the past disaster has resulted. The disasters will continue as long as the role of information technology in administrative reform is viewed from the perspective of management rationalism and the structural and behavioral realities of organizational power and politics are ignored (Kraemer 1991: 178)

The discussion above does not dispute that information technology can have an effect on organisational processes. It merely maintains that the difficulty of implementing such changes will slow these trends and that large scale organisational changes will not occur as a result of single projects such as the LSP. The LSP may induce future change projects outside the OPC but will probably not incur them directly as such changes would be very difficult to manage at the same time.

There have been many predictions that computerised information systems will have a great impact on the workings of government in general[17].

Theoretically, politicians could sit in front of terminals or workstations in parliament with access to electronic versions of principal bills and amendments in either consolidated or unconsolidated forms. Drafters could be involved in real-time amendments to these bills and amendments and this role of the government printer could be eliminated as drafters type the legislation directly onto the system the members of parliament access.

However, as discussed above, in the short term it is unlikely to occur as a direct impact of a single systems development project. As Chartrand and Ketcham stated:

In writing a report about information resources and technology for Congress, it is tempting to make the statement that Congress will conduct its business in a vastly different way 20 years from now.

But such a conclusion does not hold up well, if past performance is reflected in present reality. Congress by its nature, as the representative branch of our constitutional government, is cautious about change; it views the prospect of altering the manner in which it performs its day-to-day tasks with some skepticism[2] (p182).

These observations support Snellen and Schokker's conclusion that information technology developments within public administration are more complex as a result of the inevitable interweaving of political, judicial and technical aspects. The developers of the LSP are coping with this increased complexity by avoiding it.

The technology an organisation uses will help define the organisational structure and processes of that organisation. A parliamentary system created now, using computerised information technologies would probably be quite different to those created last century. The LSP is an example of a systems development project introducing such technologies into such an established parliamentary system. Much literature in the field of information technology has focused on the ability of IT to transform organisations and the desirability of doing so, but there are problems with implementing such changes within the space of a single computer systems development project's lifespan. While the LSP will result in major changes for the Office of Parliamentary Counsel and the administrative procedures surrounding the process of legislation, it is unlikely to directly have a substantive impact on the workings of parliament. Such changes may flow on from the implementation of the system but will probably not be a part of it.

1. Voermans, W. and E. Verharen, LEDA: A semi-intelligent legislative drafting-support system, in Legal knowledge based systems, J.S. Svensson, J.G.J. Wassink, and B.V. Buggenhout, Editors. 1993, Koninlijke vermande: p. 81-94.

2. Chartrand, R.L. and R.C. Ketcham, Opportunities for the Use of Information Resources and Advanced Technologies in Congress: A Study for the Joint Committee in the Organization of Congress (A Consultant Report). The Information Society, 1994. 10: p. 181-222.

3. Snellen, I.T.M. and J.T. Schokker. Legal Application Systems in Public Administration -some specific building requirements. in European Group of Public Administration: Study Group on Informatization in Public Administration. 1992. Pisa, Italy:

4. CIPU, Legislation System Project Business Case 1994, Tasmanian State Service:

5. Ward, J., P. Griffiths, and P. Whitmore, Strategic Planning for Information Systems. John Wiley Information Systems Series, eds. R. Boland and R. Hirshheim. 1990, Chichester, UK: John Wiley and Sons. 450.

6. Hammer, M., Reengineering Work: Don't Automate, Obliterate. Harvard Business Review, 1990. July-August: p. 104-112.

Hammer, M. and J. Champy, Reengineering the Corporation. 1990, New York, NY: Harper Business.

7. Davenport, T.E. and J.E. Short, The New Industrial Engineering: Information Technology and Business Process Redesign. Sloan Management Review, 1990. 1990(Summer): p. 11-27.

8. Davenport, T.H. and D.B. Stoddard, Reengineering: Business Change of Mythic Proportions? MIS Quarterly, 1994. 1994(June): p. 121-127.

9. Craig, J. and P. Yetton, Business Process Redesign: A Critique of Process Innovation by Thomass Davenport. Australian Journal of Management, 1992. 17(2): p. 285-306.

10. Buchanan, D. and D. Boddy, The expertise of the change agent: public performance and backstage activity. 1992, Hempstead, UK: Prentice Hall. 158.

11. Walsham, G., Interpreting Information Systems in Organisations. John Wiley Series in Information Systems, ed.^eds. R. Hirschheim and R. Boland. 1993, Chichester: John Wiley.

12. Younis, T. and I. Davidson, The Study of Implementation, in Implementation in Public Policy, T. Younis, Editor 1990, Dartmouth: Aldershot USA. p. 3-14.

13. Brinckman, H., Technological and Organisational Innovation, in Information System, Work and Organization Design, P. Van den Besselaar, A. Clement, and P. Jarvinen, Editors. 1991, Elsevier Science Publishers (IFIP): North-Holland.

14. Brussard, B.K., Information Resource Management in the Public Sector. Information and Management, 1988. 15: p. 85-92.

15. Abramson, J.B., F.C. Arterton, and G.R. Orren, The Electronic Commonwealth: The impact of New Technologies on Democratic Politics. 1988, New York: Basic Books Inc. 331.

16. Kraemer, K.L., Strategic Computing and Administrative Reform, in Computerisation and Controversy: Value Conflicts and Social Choices, C. Dunlop and R. Kling, Editors. 1991, Academic Press Inc: Boston USA. p. 167-180.

Other information obtained from documentation, interviews and observations from the Legislation System Project.

Acknowledgments: CD Keen, B Ryan and members of the CIPU and OPC for help in developing the ideas contained in this paper.

[*] Computer Science Department University of Tasmania Box 252C Sandy Bay 7005 AUSTRALIA

email: lynley.hocking@cs.utas.edu.au

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/JlLawInfoSci/1996/3.html