Journal of Law, Information and Science

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Journal of Law, Information and Science |

|

BEN MEE*

This paper discusses the problems with the decisions in The Panel Case litigation, and its implications for copyright law in the light entertainment context. The copyright reform process undertaken by the federal government is considered in some detail, with an overview of some alternative exemption models to the ‘fair dealing’ system, which was ultimately retained by the legislature. Finally, the paper examines some of the problems which may be associated with the new fair dealing exemptions for ‘parody and satire’, concluding that the uncertainty which was a major impetus for reform may not in fact have been resolved.

The inherent tension between entertainment involving parody and satire on one hand, and copyright law on the other has been a subject of extensive discussion in Australia following The Panel Case[1] litigation. Prior to the litigation, producers of light entertainment TV and radio programs had been using copyright material on the assumption that they would be protected from litigation due to industry goodwill, de minimis use or the provisions of the copyright legislation. The outcome in The Panel Case proved these assumptions to be misplaced.[2] This left the broadcasting industry in a precarious and uncertain position, and generated significant debate about the adequacy of Australian copyright law in the modern environment. Following an inquiry commissioned by the Commonwealth Attorney-General in 2005 into the need for reform of Australian copyright law as it relates to fair use,[3] the Parliament ultimately implemented a fair dealing exception for parody and satire to ‘ensur[e] that Australia’s fine tradition of poking fun at itself and others will not be unnecessarily restricted’.[4] This article considers the legislative lacunae and judicial inconsistencies exposed by The Panel Case litigation, the options available for addressing those shortcomings and the extent to which the recently enacted exceptions[5] might achieve that goal. It will be argued that while the exceptions in their current form may have assisted in The Panel Case, they may also increase uncertainty in this area of the law and afford protection to copyright owners in a way inconsistent with fundamental copyright jurisprudence.

Copyright protection in Australia is governed by the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) (‘the Act’), which provides protection for literary, musical, artistic and dramatic works as well as technological forms of expression such as film, sound recordings, broadcasts and published editions of works. Copyright subsists in television broadcasts in Australia by virtue of s 91 of the Act. Broadcast copyright includes the exclusive right to communicate the broadcast to the public by re-broadcasting or otherwise.[6] Under Australian law, broadcast copyright is prima facie infringed when a person does, or authorises the doing of, an act comprised in the copyright without license in relation to the whole or a substantial part of the broadcast.[7]

The exceptions relevant to this discussion are those contained in ss 103A and 103B of the Act, which provide that a fair dealing with an audio-visual item[8] does not constitute an infringement of the copyright in the item if it is for the purpose of criticism or review, or for the purpose of reporting news.[9] These provisions can be contrasted with the open-ended ‘fair use’ exemption which operates in the US,[10] as the Australian position requires uses to be ‘pigeon-holed’ into one of the legislative heads.

There was very little Australian authority on the applicability of the fair dealing provisions with regard to broadcast copyright at the time of the litigation,[11] and thus creators of light entertainment which did not fall squarely within one of these heads were faced with some degree of uncertainty. Such entertainment often relies on the devices of parody or satire to achieve the desired effect by imitating, using or referring to material which may be protected by copyright, in order to make some comment on that material or society in general.[12]

The uncertainty associated with the extent to which the use of parody and satire in light entertainment programs impinged on copyright law derived from three key issues. First, the question of what amounted to a ‘substantial part’ of a broadcast had not been the subject of judicial comment. As infringement requires use of a ‘substantial part’ of the copyright subject matter, it was unclear which parts of, and what quantity of copyright material could be taken without infringing. Secondly, the precise definition and bounds of the terms ‘criticism’, ‘review’ and ‘news’ had not been explored to any great degree. As such, creators of light entertainment could not assess whether a particular use of material, if substantial, was likely to fall into one of the heads of fair dealing. Thirdly, it was not entirely clear how the concept of fair dealing was to be applied, as ss 103A and 103B do not provide a ‘list of factors’ to guide the court such as those present in the research and study fair dealing provisions.[13] A leading English authority on fair dealing is the case of Hubbard v Vosper, where Lord Denning MR provided the following by way of guidance:

It is impossible to define what is “fair dealing.” It must be a question of degree. You must consider first the number and extent of the quotations and extracts. Are they altogether too many and too long to be fair? Then you must consider the use made of them. If they are used as a basis for comment, criticism or review, that may be fair dealing. If they are used to convey the same information as the author, for a rival purpose, that may be unfair. Next, you must consider the proportions. To take long extracts and attach short comments may be unfair. But, short extracts and long comments may be fair. Other considerations may come to mind also. But, after all is said and done, it must be a matter of impression.[14]

In The Panel Case, the courts were largely concerned with the issue of what constitutes a broadcast, but the litigation also provided an opportunity to clarify the law in relation to fair dealing. It will be argued that by failing to adequately consider the question of fairness, the courts actually increased uncertainty in the law. Furthermore, some of the findings on fair dealing and substantiality seem inconsistent and arguably fail to consider the interplay between the two concepts.

The Panel was a weekly television show broadcast on Network Ten (‘Ten’) which centred around discussion of topics such as current affairs, sport and the arts,[15] frequently using excerpts from other programmes as the object of discussion or to illustrate a point. In 2000, Channel Nine (‘Nine’) brought proceedings in the Federal Court alleging that Ten infringed copyright by broadcasting a variety of excerpts from Nine’s programmes between 8 and 42 seconds in duration.[16] Ten argued that it had not taken a substantial part of each broadcast and in the alternative, that its dealings with the broadcasts were fair under the Act.

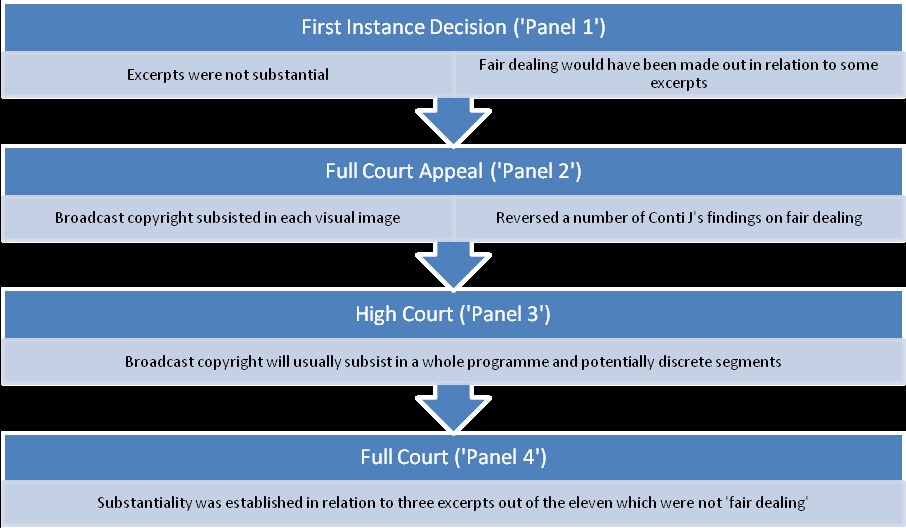

At first instance, Conti J held that Ten had not taken a substantial part of any of the broadcasts,[17] but nevertheless considered the application of fair dealing to each excerpt. On appeal, the Full Court of the Federal Court held that copyright can subsist in each visual image transmitted in a broadcast[18] and re-considered the question of fair dealing, reversing a number of Conti J’s conclusions.[19] After the High Court held that broadcast copyright ordinarily subsists in a discrete programme[20] (and possibly individual segments) rather than individual images, the matter was remitted to the Federal Court,[21] where the Full Court reconsidered the question of substantiality in relation to the excerpts.

Figure 1: Issues raised in each decision

The conclusions of Conti J in Panel 1 and the Full Court in Panel 2 on each excerpt have been outlined and discussed elsewhere,[22] but three particular excerpts illustrate a number of bases on which the decisions can be criticised. In particular, they demonstrate the potential for ad hoc and unpredictable outcomes based on subjective considerations. Examination of the ultimate result following Panel 3 and Panel 4 illustrates further the uncertainty in this area of the law and the difficulties in applying the fair dealing exceptions as they existed at the time. Some aspects of the reasoning also raise concerns about the scope of copyright protection, and whether it is being extended to protect interests which are unrelated to the protected subject matter. These concerns will be dealt with in Parts 4 and 5 of this paper.

Boris Yeltsin: In a discussion about Australia becoming a republic, an excerpt from the Today Show of Boris Yeltsin shaking hands with three successive former Russian Prime Ministers whom he had dismissed was shown. The discussion of the panellists related to the potential need for an age limit on a president.

Allan Border Medal: A clip from the presentation of the Allan Border Medal Dinner showing winner Glenn McGrath’s failure to notice the Prime Minister’s attempts to congratulate him was a second excerpt upon which the various judges disagreed. Ten argued that the moment would otherwise have remained ‘hidden’ news, as it had not been noticed by Nine’s Director of Sports and that unusual or incongruous moments in a Prime Minister’s life are inherently newsworthy.

Midday: In this extract, a clip of the Prime Minister singing happy birthday for Sir Donald Bradman on the Midday Show was played. The panellists then discussed the performance of the host (Kerri-Anne Kennerley), proposing that she must be a Labor supporter having previously made the Treasurer ‘look like an idiot’[23] by inducing him to perform the ‘Macarena’ dance on the show. Ten argued criticism and review, both of the programme itself and of Ms Kennerley’s role in it.

Conti J considered that the use of the Boris Yeltsin excerpt would not have been fair dealing for the purpose of reporting news because his Honour considered that the purpose of the re-broadcast was that of entertainment rather than the reporting of news ‘as a matter of judgment and impression’.[24] In Panel 2, the Full Court upheld Conti J’s finding, with Hely J recognising that this was a ‘matter on which different persons might legitimately hold different conclusions’.[25] Sundberg J, having ‘watched the broadcast several times, on each occasion thinking it could reasonably be concluded either that the defence was made out or it was not’[26] concurred. Finkelstein J dissented, considering that ‘[t]he discussion whether there should be an age limit imposed on a president, while considered in a humorous way was newsworthy and that is all that is required’.[27]

In relation to the Allan Border Medal excerpt, Conti J considered that fair dealing for the purpose of reporting news would have succeeded on the basis that ‘unusual or incongruous moments in a Prime Minister’s life are inherently news’[28] and that the incident may have remained unnoticed had it not been pointed out. On appeal, the Full Court unanimously held that the defence was not made out, with Hely J noting that ‘the only public embarrassment was created by The Panel’s publicizing of a background and unnoticed incident’.[29]

When considering the Midday excerpt, Conti J held[30] that the purpose of the dealing was to ‘satirise aspects of Ms Kennerley’s performance’ and not criticism or review of Midday ‘as an issue of fact and degree’. In Panel 2, Hely and Sundberg JJ held that neither reporting news nor criticism and review could be made out as the segment was shown ‘for its own sake, either as something worth seeing again, or for the benefit of those who had missed it when it was originally broadcast’.[31] Finkelstein J considered that both exemptions could be made out because of the discussion of Ms Kennerley’s talents as a host, and because a Prime Minister’s perceived indiscretions warrant reporting.[32]

When reconsidering the substantiality issue in light of the High Court’s decision in Panel 3, the Full Court unanimously held that the Boris Yeltsin extract did not infringe, with Finkelstein J concluding that the use was ‘insignificant’ and caused ‘absolutely no injury to Nine’s interests’.[33] When considering the Allan Border Medal excerpt, Finkelstein and Sundberg JJ held that the extract was substantial, being ‘plainly a material and important part of the programme’.[34] In dissent, Hely J considered that the material was not a substantial part as it was ‘trivial, inconsequential or insignificant in terms of the source broadcast’.[35] Finally, the Court unanimously held that the Midday segment was substantial, being ‘potent footage’ which ‘provided entertainment in its own right’.[36] When discussing this issue, Finkelstein J noted that one of the panellists had said the footage should be included in the Midday show’s ‘best of’ special.[37]

Table 1: Conclusions of each court

|

Excerpt

|

Defence Pleaded

|

Conti J

|

Full Court: Fair Dealing

|

Full Court: Substantiality

|

|

Boris Yeltsin

|

News

|

No

|

No (2:1)

|

Insubstantial

|

|

Allan Border Medal

|

News

|

Yes

|

No

|

Substantial (2:1)

|

|

Midday

|

News

|

No

|

No (2:1)

|

Substantial

|

|

Criticism & Review

|

No

|

No (2:1)

|

Much of the criticism which followed the litigation related to the methodology applied by the courts in relation to determining the ‘fairness’ of the dealings.[38] In Panel 1 Conti J extracted a number of short ‘principles’ from the case law relevant to the issue of fair dealing, the most problematic being that ‘fair dealing involves questions of degree and impression’.[39] This ‘statement of principle’ was taken from the judgment of Lord Denning MR in Hubbard v Vosper[40] (extracted above) but as Handler and Rolph have noted,[41] its context has largely been omitted. For Lord Denning, the matter of fair dealing was one of impression ‘after all is said and done’[42] while the judges in The Panel Case arguably used their subjective ‘impression’ as the primary, if not sole basis on which to decide the issues.

The Boris Yeltsin excerpt is perhaps the clearest example of the problematic approaches of the courts. In Panel 2, Sundberg J was unable to decide whether the defence was established or not and simply upheld Conti J’s decision without expressly attempting to apply any of the principles espoused in Hubbard v Vosper to inform a conclusion one way or the other. His Honour stated that it could reasonably be concluded that the defence was made out or it was not. Given the Court’s repeated assertions that the test of fairness is objective, one would presume that the use of an extract which could reasonably be concluded to be fair would suffice. In Panel 4 however, his Honour agreed with Finkelstein J’s view that the use of the extract was insignificant and caused no harm to Nine’s legitimate interests. Had Sundberg J relied on, and applied the fully extracted passage from Hubbard v Vosper in Panel 2, it is difficult to see how his Honour would have concluded that the use of an excerpt which he later labelled harmless and insignificant was not fair dealing.

In reaching the opposite conclusion on the fair dealing issue, Finkelstein J considered that the newsworthiness of the discussion was, of itself, sufficient to satisfy the defence without examining whether the dealing was fair. His Honour explained why the discussion was newsworthy but provides no guidance as to why the dealing with the excerpt was fair.

In relation to the other two excerpts, there is no clear agreement amongst the judges, and no guidance as to why the use was, or was not fair.[43] What was made clear, if anything, was the need for a re-examination of the fair dealing provisions in a way which requires a balancing of the competing interests of users and copyright owners.

It has been noted that following Panel 2, there was significant outcry from the legal, media and entertainment sectors.[44] In particular, the comments in the media that the judges had failed to recognise obvious examples of criticism and news reporting[45] exemplify the critical shortfall of fair dealing: that it requires an artificial pigeon-holing of material into limited legislative heads, which in turn are prone to conservative,[46] formalistic and rigid interpretation by the courts. Indeed, there are few other areas of law where such extensive reliance on the dictionary definition of words is seen.[47] Furthermore, gaps in the legislative framework are often only exposed by litigation, and thus can only be rectified post hoc by the legislature, providing little comfort to unfortunate users in test cases like The Panel Case.

The outcome of The Panel Case was not the only impetus for the Fair Use Inquiry. Two other key factors were the negotiations leading to the Free Trade Agreement between Australia and the US (AUSFTA), and concerns over the inadequacy of the Act in the modern electronic environment.[48] The AUSFTA negotiations resulted in a ‘breathtakingly long, detailed and opaque’[49] chapter of the AUSFTA dealing with intellectual property, with a large focus on extension of the copyright term and concerns about circumventing technological protection measures in the ‘digital age’.[50] It has also been noted that the AUSFTA, despite its complexity, contained no notable provisions dealing with exemptions to copyright infringement.[51] In light of these considerations, the federal government called for submissions on the Fair Use Inquiry, with a particular focus on the adequacy of the fair dealing provisions in ‘providing a balance between the interests of copyright owners and copyright users’.[52] As the US-led extension of copyright duration in the AUSFTA process was non-negotiable, there was a push by user groups for the government to consider the implementation of a US-style ‘Fair Use’ exemption to ‘rebalance’ the law.[53] The United Kingdom had also recently completed a comprehensive review of intellectual property issues in the Gowers Review,[54] which provides some alternative perspectives on the suitability of fair dealing and the role of copyright law in the modern environment.[55]

This Part of the paper examines the review process in Australia, and assesses the three main options for reform which were considered in that process: fair dealing, fair use and ‘flexible dealing’. While the amending legislation ultimately retained the fair dealing model, it is suggested that the complete abandonment of the ‘flexible dealing’ exemption for parody and satire may have been too hasty (despite extensive criticism of its structure). It may be that the resulting provisions will do little to address the fundamental problems of uncertainty in scope and judicial subjectivity highlighted by The Panel Case.

The starting point for any copyright exemption is Article 13 of the Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property (‘TRIPS’), which all World Trade Organisation (WTO) members are party to. That Article sets out the minimum requirements for any limitation or exception to exclusive rights, which must be confined to:

• certain special cases;

• which do not conflict with a normal exploitation of the work; and

• do not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the right holder.

The WTO has a dispute resolution system whereby member states can challenge the validity of any other member country’s copyright exceptions.[56] Outside of licensing and specific personal use provisions, two main models for copyright exceptions in the commercial arena have developed: fair dealing and fair use. However, the federal government also explored the option of a ‘flexible dealing’ provision for parody and satire, which relied heavily on the terms of the three-step test in Article 13. The government appears to have been unable to clearly select one model as superior in the context of parody and satire. Some commentators have suggested that the Issues Paper initially operated on a foregone conclusion that the US-style fair use provision would be the optimal solution.[57]

The first draft of the amending legislation placed parody and satire within a flexible dealing provision, but the Parliament ultimately enacted a fair dealing exemption for parody and satire. Table 2 provides an overview of the nature, advantages and common criticisms of each of these approaches and the discussion which follows considers the particular features which may have induced the government to settle for the fair dealing approach.

Table 2: Comparison of reform options

|

Approach

|

Nature

|

Key Advantages

|

Key Disadvantages

|

|

Fair Dealing

|

Fixed categories and judicial determination of fairness

|

• Certainty and

predictability[58]

Existing body of case law

|

• Many uses barred at outset

• Unpredictable for marginal cases

• No clear judicial guidance on ‘fairness’

principles

|

|

Fair Use

|

Open-ended provision with judicial assessment of certain factors

|

• Complete flexibility as to ‘categories’ of use which

can be argued

• No need for legislative post hoc review

|

• Potential for excessive judicial discretion

• No legislative guidance for novel uses

• US model may not translate to Australian law

|

|

Flexible Dealing

|

Fixed categories and judicial assessment of specific issues

|

• Requires clear principled assessment of how a use affects

legitimate copyright interests

• Does not grant protection beyond legitimate scope of

copyright

|

• ‘Special case within a special case’ may be too

restrictive

• Uncertainty in using international trade law definitions

|

Fair dealing has been the preferred approach of many common law jurisdictions, a concept which has ‘evolved as an integral part of copyright’.[59] Fair dealing exemptions were enacted in the UK and Australia early in the 20th century.[60] The provisions found in the Copyright Act 1968 are clearly derived from this early exception, which provided that ‘any fair dealing with any work for the purpose of private study, research, criticism, review or newspaper summary’ did not amount to infringement.[61] However, De Zwart has noted[62] that early UK case law recognised a more general form of fair dealing. In Cary v Kearsley,[63] the Court stated that ‘a man may fairly adopt part of the work of another: he may so make use of another’s labours for the promotion of science, and the benefit of the public’. The limitations of the modern form of fair dealing were highlighted in a recent UK decision, where Laddie J stated that heads of fair dealing are ‘not to be regarded as mere examples of a general wide discretion vested in the courts to refuse to enforce copyright where they believe such refusal to be fair and reasonable’.[64]

The essential theoretical advantage of a closed fair dealing exception is certainty in scope of application, allowing owners and users of copyright material to predict whether a use falls within a recognised category. This avoids the uncertainty associated with bringing actions for novel uses in a fair use system, where there is arguably much more scope for the court to rely on policy factors to influence outcomes. While some uses will clearly not fall within any of the heads, the above discussion shows that the supposed certainty and clarity of application was at best undermined by The Panel Case. The litigation showed not only that the definition of each head is unclear, but also the discrepancies in how different judges apply the provisions. In the Intellectual Property Research Institute of Australia’s response to the Issues Paper, Weatherall[65] identifies some other commonly mentioned drawbacks of Australia’s fair dealing provisions including the narrow interpretation of the heads with excessive emphasis on purpose rather than fairness, the ad hoc approach to fairness and importantly, the absence of a flexible outlet for exceptional cases, including the doubt relating to the existence of a ‘public interest’ exception.[66] The result is to ‘simply bar at the outset certain socially useful, transformative uses which are quite arguably within the intent of the statutory purposes without ever getting to the issue of fairness’.[67]

As noted in the submission, it is far easier for a non-expert to gauge whether a use is fair by considering the nature of a work, the nature of the use and any potential for interference with the copyright owner’s market than to gauge what may be held to be ‘criticism or review’ or ‘the reporting of news’.[68] In light of The Panel Case and the above discussion, it may be that this task is no less daunting for experienced Federal Court judges.

As such, the option of a new or modified fair dealing exception would only ‘ensur[e] that Australia’s fine tradition of poking fun at itself and others will not be unnecessarily restricted’ if the statutory purpose was framed broadly or interpreted flexibly so that the ‘purpose hurdle’ can be cleared by a broad range of uses which might be considered ‘light entertainment’. This would allow the question of fairness to be considered fully by the court, without placing undue weight on whether the use falls within a recognised head. One solution would be to adopt an inclusive approach like that available under the European Information Society Directive, which allows members to exempt purposes ‘such as criticism or review ... use[d] ... in accordance with fair practice’.[69]

The Federal Parliament ultimately retained the ‘closed’ model of fair dealing in Australian copyright legislation, and simply added an additional head of ‘parody and satire’ which applies to both works[70] and audio-visual items.[71] The possible rationale for retaining this model is discussed later in this Part. As will be argued in Part 5 of this paper, these new provisions may in fact run contrary to the goal of increasing certainty and predictability in the law. However, it is convenient to consider here the alternative options for dealing with the issue which were abandoned or rejected in the reform process.

The ‘Fair Use’ approach favoured in the US is embodied in s 107 of its Copyright Act of 1976, although the exemption had existed at common law since the 1841 decision of Folsom v Marsh.[72] Section 107 provides that copyright is not infringed by the fair use of copyright material, determined by a consideration of:

1. the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for non-profit educational purposes;

2. the nature of the copyrighted work;

3. the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

4. the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

The section lists purposes such as criticism, news reporting and scholarship by way of example but the provision is open-ended. There is clearly some overlap with the fair dealing exemptions, but the model allows the legitimacy of novel uses to be assessed by the courts. The key advantage of such a model in this area is that it removes the need for the legislature to try and contemplate every possible emerging use[73] and then engage in post hoc review, as was seen with The Panel Case. The Gowers Review[74] suggests that the fair use approach opens up ‘a commercial space for others to create value’ while the fair dealing exceptions may ‘stunt new creators from producing work and generating new value’.[75]

Weatherall has argued that fair use would address the shortcomings of fair dealing by encompassing emerging uses, requiring the courts to analyse fairness in accordance with statutory factors and providing flexibility[76] in uses which might lie at the margins of criticism and review or reporting of news. On the other hand, De Zwart has suggested that it would be wrong to regard fair use as a ‘fix-all provision’.[77] While she noted that parody might be better protected under a fair use provision, the step-by-step approach of the US courts in applying fair use is said to reduce the flexibility of the model.[78]

Another issue associated with fair use is the divergence in academic circles as to whether it complies with the three-step test outlined in the TRIPS agreement, particularly on the issue of being ‘confined to special cases’.[79] While this is a valid consideration in the law reform process, a complete discussion is beyond the scope of this paper. However, proponents of fair use may take some comfort from the decision of the WTO Dispute Settlement Body that ‘there is no need to identify each and every possible situation to which the exception could apply, provided that the scope of the exception is known and particularised.’[80]

Despite the inherently flexible nature of fair use and its potential to rectify the key problem of post hoc legislative amendments, its breadth might exacerbate the judicial reliance on subjective ‘matters of impression’ seen in The Panel Case. Furthermore, the applicability of the US model to Australian conditions is unclear, as its jurisprudential basis has been said to be ‘bound up with constitutional guarantees of free speech’.[81]

As noted above, the initial draft of the amending legislation would have included parody and satire in s 200AB of the Act, a section which incorporates the requirements of the three-step test introduced by Article 9(2) of the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works (‘Berne Convention’). The provision initially provided that copyright will not be infringed if:

(a) the circumstances of the use amount to a special case [the ‘Special Case’ issue];

(b) the use is [for the purpose of parody or satire];

(c) the use does not conflict with a normal exploitation of the work or other subject-matter [the ‘Conflict’ issue];

(d) the use does not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the owner of the copyright or a person licensed by the owner of the copyright [the ‘Prejudice’ issue].

The terms in paragraphs (a), (b) and (c) were statutorily defined as having the same meaning as in the TRIPS agreement.

The inclusion of parody and satire in this provision appeared to be somewhat anomalous, as the other permissible uses related to educational institutions and libraries. Two key criticisms were made of the provision. Firstly, the ‘three step test’ was arguably made into a ‘four step test’, by requiring proof of a ‘special case’ as well as proof that the use was for the purpose of parody or satire, rather than making parody or satire the ‘special case’.[82] The key criticism is that ‘special case’ is a term designed to assess the scope of particular exceptions rather than determine outcomes in individual cases.[83] The second major objection was the potential uncertainty which would flow from tying the definitions in domestic legislation to the international interpretation of the terms. Weatherall has highlighted[84] the impracticability of providing legal advice to creators of entertainment under such a regime, outlining the curious scenario of applying Australian and UK case law on the question of fair dealing for criticism and review, but having to consider international trade cases when arguing the parody and satire exemption under s 200AB. These criticisms are clearly valid, and it is arguable that the second of these criticisms may have loomed large in the mind of drafters when the decision was made to incorporate parody and satire into fair dealing. However, these particular shortcomings may have been given too much weight in abandoning the three-step test for parody and satire entirely. Assuming that the purpose of parody and satire could be defined to be the ‘special case’ contemplated by Article 13, it is useful to examine how a court might have applied these provisions.

The three-step test was introduced in 1967 in the form of Article 9(2) of the Berne Convention, which provides that:

It shall be a matter for legislation in the countries of the Union to permit the reproduction of…works…in certain special cases, provided that such reproduction does not conflict with a normal exploitation of the work and does not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the author.

It has been noted that although the provision was adopted unanimously at the Stockholm Conference, ‘there is still considerable uncertainty and even ambiguity over its scope’.[85] Although a detailed analysis of the three-step test is beyond the scope of this paper, some basic principles are outlined below.

The principles relating to interpretation of the three-step test were explored in the US Fair Use Decision,[86] a key decision by the WTO Dispute Settlement Body. Assuming the purpose of parody and satire would be a ‘special case’, the relevant principles would be those enunciated in relation to the Conflict and Prejudice principles.

On the Conflict issue, it was stated in the US Fair Use Decision that the use must ‘enter into economic competition with the ways that rights holders normally extract economic value from that right to the work and thereby deprives them of significant or tangible commercial gains’.[87] This would require consideration of existing exploitation of the copyright subject matter as well as plausible future uses. In a comprehensive analysis of the three-step test, Ricketson considered that the question may be whether the potential use is of considerable or practical importance and that normative issues of public policy may also be relevant. [88]

Regarding the Prejudice issue, the US Fair Use Decision held that prejudice to legitimate interests would be unreasonable if the exception causes or has the potential to cause an unreasonable loss of income to the copyright holder.[89] Importantly, Ricketson has noted that the legitimate interests include economic and moral rights, and that substantial usage is not necessarily unreasonable. [90]

The key advantage of incorporating these principles is that such a model compels the court to objectively assess a particular use by reference to the underlying principles of copyright protection rather than subjectively as ‘matters of impression and degree’. That is, the court is taken outside the more opaque confines of the 'fair dealing' model and instead required to address more transparently how, and to what extent impugned uses might detract from the owner’s actual and potential uses rather than relying on questions of ‘impression and degree’. The Gowers Review took a similar approach to the issue, suggesting that a court should expressly consider commercial interests and artistic integrity within the bounds of copyright protection.[91] Furthermore, it highlighted that creators can still use defamation laws to prevent works which are offensive or damaging to a creator rather than to the work itself from being made available.[92] Importantly, the original s 200AB model expressly recognised that parody and satire will often occur in the commercial market.[93]

It might be argued that in light of the uncertainty associated with the ‘three-step test’ in international copyright jurisprudence, such an approach would in fact lead to greater uncertainty in this area and place parodists and satirists in a more precarious position than the fair dealing approach which was ultimately adopted. It is not suggested that overcoming some of the uncertainties associated with the ‘three-step test’ would be a simple task, but to some extent this is part of the reason that the author contends a novel flexible dealing approach may be preferable. The raft of amendments to the Act (particularly through the ‘digital era’) has resulted in an incredibly complex piece of legislation, which may in part reflect repeated attempts to address new problems within existing frameworks. The introduction of a novel test which requires a focus on legitimate interests and ‘normal exploitation’ would, as with any new statutory formulation, require Australian courts to consider these issues without the benefit of extensive precedent. But by doing so outside the framework of the existing fair dealing model and its own deficiencies, such a test actually compels more explicit judicial analysis of what these interests and exploitation rights actually are. To raise the potential for initial uncertainty as a justification for abandoning an approach which could progressively clarify much of that uncertainty is to foster an ad hoc, piecemeal approach to law reform in an area which arguably needs exactly the opposite.

Examination of the first[94] (‘EM1’) and second[95] (‘EM2’) explanatory memoranda released for the s 200AB model and the fair dealing model provides some insight into how the provisions were intended to operate and the justification for choosing a particular form. Although it will be for the courts to determine whether to depart from the fair dealing approach seen in The Panel Case, some of the remarks in EM2 suggest that the failure to clearly consider the rationale of copyright in that case was an example of a more systemic problem in copyright law rather than an anomaly. Most worrying is the express reference to the inherent scorn or ridicule of creators and performers involved in satire as a justification for requiring that a use be ‘fair’. As will be argued below in Part 5, such an approach goes beyond the legitimate interests protected by copyright and allows copyright owners to use their statutory rights as the basis of a much wider cause of action.

EM1 provided that s 200AB was intended to provide a ‘flexible exception to enable copyright material to be used for certain socially useful purposes while remaining consistent with Australia’s obligations under international copyright treaties’.[96] It suggests that the ‘special case’ requirement was intended to ‘ensure that the use is narrow in a quantitative as well as qualitative sense’.[97] Given the ‘threshold’ role of the substantial part test in s 14 of the Act, there is a legitimate argument that this aspect might have proved to be problematic[98] as the exception can only come into consideration once substantiality has been established. The stated purpose of the ‘conflict’ and ‘prejudice’ requirements reflected the principles from the US Fair Use Decision discussed above, requiring the court to consider whether the use ‘deprives copyright holders of significant or tangible commercial gains’ and ‘an assessment of the legitimate economic and non-economic interests of the copyright owner’.[99] Furthermore, the section expressly recognised that parody and satire will often ‘take place in the commercial media or other commercial setting’.[100] Finally, the intention behind tying the definitions to the Article 13 interpretations was that the phrases ‘should not be interpreted more narrowly than Article 13 requires’.[101]

What is clear is that the intention behind s 200AB was to provide the maximum protection for parody and satire permitted under Australia’s international obligations. The two key problems of requiring a ‘special case within a special case’, and of using the international interpretations of the conflict and prejudice requirements, could easily have been overcome by redrafting the provisions to make parody and satire the ‘special case’, and to crystallise the definitions of the conflict and prejudice requirements through a careful consideration of the current views on their content. While it is arguably undesirable to require IP advisors to consult international trade law materials to advise clients on each use, the government could have consulted with experts in the field to provide statutory definitions flexible enough to encompass shifts in international jurisprudence, but which do not depend on international law for their content.

A provision redrafted in this way could have avoided the excessive focus on purpose seen in The Panel Case, where uses that the court held could be criticism and review were held not to be fair dealing as they were purportedly not fairly uses for criticism and review. This provision would simply require a threshold assessment of whether a use could be said to be parody or satire[102] and if so, the court would be required to state whether or not, and how the use deprives the copyright owner of commercial gains or unreasonably prejudices legitimate interests associated with copyright. It is submitted that this is preferable to judicial assessment as a ‘matter of impression’.

EM2 recognised that parody and satire are likely to overlap with the reporting of news, and criticism and review.[103] However, there was also a comment that it is appropriate to require the use to be fair as parody is likely to involve holding up a creator or performer to scorn or ridicule.[104] That paragraph further provides that satire is said not to involve direct comment but as it uses material for a general point, it should not be unfair in its effects for the copyright owner.

What is disconcerting is the potential for undue weight to be placed on the content of the use and the nature of the comment on an individual or institution, and more particularly its effect on the copyright owner’s reputation. Under the open-ended fair use model in the US, commentators have highlighted the potential for judicial distaste for the content of a use to influence the outcome of cases. In DC Comics Inc v Unlimited Monkey Business,[105] the characters ‘Super Stud’ and ‘Wonder Wench’ were used to deliver adult singing telegrams. The court referred to ‘implicit disparagement and bawdy associations’ resulting from the parody and the possibility of damage to the reputation of the authors. Given the scope of judicial discretion inherent in the ‘fairness’ aspect of fair dealing[106] and the lack of unifying principles in its application, it is not difficult to envisage similar problems arising before the Australian courts where a use is clearly identified as ‘parody’ or ‘satire’. The advantage of a ‘flexible dealing’ model is that it would require the court to articulate why such uses unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the copyright owner, rather than whether it is simply unfair in its effects for the copyright owner. The importance of the distinction is articulated in the Gowers Review:

The crucial point should be whether transformative use compromises the commercial interests of the original creator or offends the artistic integrity of the original creator ... Enabling transformative use would not negate ... the right to be identified and the right to object to derogatory treatment [of the copyright subject matter]. Creators would still be able to use defamation laws to prevent works that are offensive or damaging to the original creator from being made available.[107]

What came out of The Panel Case saga was a clear need to clarify the law in this area and perhaps more importantly, define more precisely exactly what copyright protects. The extensive review process provided the opportunity for a paradigm shift in Australian copyright law by implementing a novel approach to copyright protection which would have required a court to approach copyright cases on a utilitarian basis. The ultimate result however, was rejection of the alternative models in favour of retaining the time-tested fair dealing style exemptions. The remaining Part of this paper examines how these new provisions may be interpreted and applied, with a closer focus on how these provisions may lead to further uncertainty and potentially extend the scope of protection granted by copyright in an impermissible way.

After the heavy criticism of the proposed use of s 200AB for parody and satire, the Parliament ultimately enacted ss 41A and 103AA which provide that a fair dealing with a work or audio-visual item for the purpose of parody or satire does not infringe copyright. Three key issues which may arise in relation to these new provisions are considered below:

1. How will ‘parody’ and ‘satire’ be defined and distinguished?

2. How will the question of fairness be determined in light of The Panel Case?

3. How will the provisions interact with the rest of the legislative framework?

On the first issue, the US position on parody and satire will be examined and compared to comments in The Panel Case and academic literature, concluding that the US definitions will not translate effectively into these new provisions. The second issue revisits the problems in The Panel Case and considers the potential for the personal views and traits of judges to influence the result of cases. Finally, the provisions in the Act relating to substantiality and moral rights will inevitably be considered alongside the question of fair dealing, an interaction which may create further uncertainty and unnecessary complexity in this area.

The terms ‘parody’ and ‘satire’ are not defined in the legislation, although De Zwart notes the express recognition during the Senate Committee hearings that the meanings of the terms were open to various interpretations.[108] The Fact Sheet released by the Attorney-General’s Office identifies the potential for overlap between the terms[109] and provides some insight into the legislative intention. It provides that satire often involves ‘attacking an idea or attitude, an institution or social practice, through irony, derision, or wit’. Parody is said to involve ‘the imitation of the characteristic style of an author or a work for comic effect or ridicule’. De Zwart has identified[110] three possible influences on the Australian courts in interpreting these sections:

• US case law on parody and satire.

• Dictionary definitions.[111]

The meanings of the terms in literary criticism and other disciplines.[112]

In the context of parody and satire, the US courts have conducted the fair use analysis in a ‘transformative use’ framework since the decision in Campbell v Acuff-Rose Music Inc[113] (‘Acuff-Rose’). The impugned use in that case was a rap parody of Roy Orbison’s ‘Oh, Pretty Woman’ which was commercially released. What emerged from the case was a principle that the courts will be more likely to find fair use if the new user has clearly added something new to the copyrighted material.[114] The Court suggested that parodies represented ‘a desired form of social commentary’,[115] consistent with the goal of stimulating ‘the creation and publication of edifying matter’ by targeting another work.[116] By contrast, the US courts have consistently rejected satire as falling within fair use. In Dr Seuss Enterprises v Penguin Books USA Inc[117] (‘Dr. Seuss’) the use of the ‘Dr. Seuss’ style of rhyming to comment on the O J Simpson fiasco was considered likely[118] to have infringed copyright because as a mere satire, it simply used the style of another recognisable work as a weapon to make some broader comment.[119] Thus the distinction drawn by the US courts is between parody as a targeting of the work which is used, and satire as a use of a work as a weapon to target society or institutions more broadly.[120] In the fair use framework, parody is protected as it ‘needs to mimic an original to make its point’ while satire is not as it can ‘stand on its own two feet and so requires justification for the very act of borrowing’.[121] As satire is expressly included in the Australian exemption, it would seem unlikely that the Acuff-Rose ‘weapon-target’ approach could be relied on very closely, as this would almost certainly rule out satirical uses as ‘fair’.[122]

It is convenient to consider here how the Panel excerpts may have fared under a fair use provision. Segments such as the Boris Yeltsin, Midday and Allan Border Medal excerpts discussed above would clearly fall on the side of satire under this formulation,[123] as there was no imitation or transformation involved. The Boris Yeltsin and Midday segments used the excerpts to comment on the wider issues of the republic debate and the political leanings of Ms. Kennerley respectively. On the other hand, the Allan Border Medal segment could arguably be said to have created something new, by highlighting an incident which was previously unnoticed. Of the three segments, the Allan Border Medal excerpt is arguably the one that involved the least critical analysis or new insight by the panellists, but might have been the only one of the three to satisfy the exception as applied in the US. However, in Sandra Kane v Comedy Partners[124] (‘Sandra Kane’) the New York District Court had to consider whether the use of a six-second excerpt of the plaintiff dancing in a bikini to introduce a segment on a comedy show was a fair use. It was held that despite not being a parody, the use of the material in this context was fair in the circumstances. De Zwart has noted that this contextual view of fairness is much broader than The Panel Case approach,[125] as it avoids the need for detailed analysis of each use and the accompanying commentary. This contextual approach may in fact translate well to Australian law, avoiding some of the problems of The Panel Case by requiring a threshold assessment of context and a separate consideration of fairness.

In Panel 1, Conti J relied on the Macquarie Dictionary definitions of parody and satire, considering that the essence of the former is imitation while satire is a ‘form of ironic, sarcastic, scornful, derisive or ridiculing criticism of vice, folly or abuses.[126] Sainsbury has identified from academic literature that the key indicators of parody are ‘imitation of an existing work to which changes are made with the aim of commenting on or criticising’.[127] Satire is said to be an attack, in the form of playful aggression with the aim to ‘provide amusement at the same time as making a judgment’.

It is suggested that the use of the broad words ‘parody or satire’ and the wide range of associated interpretations is designed to address the ‘pigeon-holing’ concern identified by The Panel Case. Humorous uses of copyright material in the context of light entertainment will not be ‘barred at the outset’ if they cannot be classified as criticism or review, or reporting of news. Rather, use for ‘parody’ or ‘satire’ should be prima facie obvious in most cases and thus a judicial analysis of fairness may be undertaken. This approach is supported by the comments of the Attorney-General in relation to the provisions: ‘[a]n integral part of [a comedian’s] armory is parody and satire — or, if you prefer, “taking the micky” out of someone.’[128]

Thus a broad contextual analysis as seen in Sandra Kane may be adopted by the courts in determining whether the general context of the use was ‘taking the micky out of someone’. The question of fairness could then be assessed by reference to the Hubbard v Vosper factors such as proportions of original and new material, amount taken and what the new use conveys. However, the approach to fair dealing taken in The Panel Case may, if applied in relation to the new provisions, create the same problems of subjective assessment as it did during the litigation.

As argued by Handler and Rolph, and in Part 3 of this paper, the approach to fair dealing in The Panel 1 and The Panel 2 relied too heavily on the ‘matter of impression’ criterion and ultimately led to a subjective assessment of each excerpt as to whether it impressed the judge as falling within a recognised head of fair dealing. Should this approach be applied to the new provisions, there may be concerns that the legitimacy of a use may depend on a judge’s sense of humour. The unpredictability of this approach is recognised in The Panel 2 by each of the judges, commenting that ‘different minds can reasonably come to different conclusions’[129] and that ‘we are in the realm of decision-making where there is room for legitimate differences of opinion as to the correct answer’.[130] It is difficult to see how certainty and predictability can be achieved if the fairness of a particular use depends on whether it impresses the judge as parody or satire. In the US Fair Use framework, it has been argued that the courts have often assumed at the outset that a use has no legitimate value as a work and thus failed to ‘rigorously pursue the fair use doctrine’.[131] Gowers has referred to IP as ‘a priesthood on the one hand and a lobbyist’s playground on the other’, enacted by ‘quite funny men of a certain age in legal chambers, dusty files all around them’ and noted that IP holders are usually well organised, articulate and well financed while users are diffuse.[132] The potential uncertainty in the scope of the exemption arising from subjective assessments in judgments places the user in a more precarious position vis-à-vis the copyright owner. Rather than being required to assess the impact of their use on the copyright holder’s legitimate interests, the user may be required to place themselves in a judge’s shoes and assess whether the use for light entertainment would be considered parody or satire as a matter of impression. On this approach, it is arguable that the provisions would do little to facilitate these new uses.

However, the sections may be more certain in scope if the reasoning in The Panel Case is viewed as anomalous and the more complete analysis outlined in Hubbard v Vosper is undertaken. Sainsbury has suggested that weighing up how much original material is included against the material taken may be an important factor, as will the effect of the dealing on the market for the original work.[133] On this point, the US courts have been careful to acknowledge that ‘it is legitimate for parody to suppress demand for the original by its critical effect’,[134] and distinguish this effect from substitutive competition in the market for the original, which tends against a finding of fairness. The question of quantity and proportions raises some further issues, considered below. Essentially, the provisions may be more workable once a clearer and more principled approach to fair dealing emerges from the courts than what was seen in The Panel Case.

A final issue of concern is how the new exceptions will interact with other provisions in the Act. Firstly, the quantity of copyright subject matter which a parodist or satirist takes may significantly impact on what they can legitimately do with the material. Secondly, it is unclear how the moral right of integrity sits alongside the new exemptions. Adding further to the confusion is the potential overlap with, and the proper role of defamation law in this area.

Clearly, a parodist or satirist who takes less than a ‘substantial part’ of copyright subject matter does not infringe any of the owner’s economic rights regardless of how he or she uses that material. In the case of broadcasts, The Panel 4 established that the test is whether what was taken was ‘essentially the heart’[135] of the broadcast while for works, the issue is determined qualitatively. This raises some interesting issues, particularly in relation to satire. In US fair use law, the courts have stated that while the parodist must be able to use enough for the audience to recognise the reference, he or she cannot take so much that it will become a market substitute for the original.[136] As parody needs to use the copyrighted material to ‘quickly conjure up a reference to the audience’,[137] it seems logical that the original or essential features (ie a substantial part) of the copyright material will ordinarily be taken and thus the parodist will in most cases need to rely on the fair dealing exemption to avoid liability.[138]

By contrast, The Panel Case established that it is possible for a satirical use of copyright material to be insubstantial despite not being a fair dealing.[139] As outlined above in Part 4, one of the criticisms of incorporating parody and satire into s 200AB was the difficulty in advising clients on separate sets of principles for fair dealing on the one hand, and ‘flexible dealing’ on the other. A satirist may avoid liability without relying on the fair dealing provisions by taking an insubstantial part of copyright material and using it as he or she pleases. At the same time, the satirist who takes the ‘the heart’[140] of the material to make a comment will be subject to the ‘fairness’ assessment of the court. While effective satire often relies on subtlety, users may seek to make the comment more obvious so as to clearly impress the court that the use is satirical and not merely ‘pretence for some other form or purpose’.[141] Thus there is the possibility of the provisions promoting ‘weaker’ satire, by encouraging uses which are either unlikely to induce the owner to bring an action or which take ‘insignificant’ parts and attempt to make the satirical comment less forcefully.

A key concern is that in borderline cases, findings on substantiality may potentially drive the outcome of the ‘fairness’ assessment. A detailed consideration of the social benefit of the parody or satire and its impact (if any) on the copyright owner’s legitimate interests may give way to a more crude assessment of ‘what’ or ‘how much’ of the subject matter was taken. Focusing on the subject matter rather than the copyright itself arguably leads to more fact-based development of the case law in this area, and discourages judicial development and elaboration of the legitimate interests protected by copyright. Adding to the confusion is the lack of authority on how the substantiality test in The Panel 4 will be applied, as well as the potential interaction with moral rights provisions.

Moral rights are granted by the Act in respect of literary, dramatic, artistic and musical works, as well as cinematograph films.[142] In this context, the most important moral right granted by the Act is the right not to have a work or film subjected to derogatory treatment. Section 195AI(2) grants this right, which is infringed by:

(a) doing anything that results in a material distortion, mutilation or alteration to the work which is prejudicial to the author’s honour or reputation; or

(b) doing anything else in relation to the work that is prejudicial to the author’s honour or reputation.

The Explanatory Memorandum to the amending legislation which introduced moral rights[143] states that paragraph (b) is intended to address instances where a work is used in an inappropriate context. It is a defence to infringement to prove that the treatment was reasonable in the circumstances.[144] Sainsbury[145] provided a comprehensive overview of the interplay between economic and moral rights in this context but noted that paragraph (b) will be of particular relevance in The Panel Case scenario, commenting that reasonableness may be established where ‘no more is taken than is necessary’ to achieve the genuine purpose of parody or satire.[146] As outlined above, the explanatory memorandum suggests that the potential harm to an author’s reputation may go to the question of fairness in relation to economic rights and thus there may be legitimate concerns that the distinction between the interests protected by economic and moral rights may be blurred. Sainsbury suggests that either a ‘ranking’ of the fair dealing and moral rights provisions or a presumption of reasonableness upon proof of fair dealing might be incorporated into the legislation to clarify this issue.[147]

One final problem with a ‘no more than necessary’ approach to parody and satire is the potential for the reputation of third parties being relevant to decisions in this area. Although The Panel Case was concerned solely with economic rights,[148] some of the comments noted above suggest that the inherent ridicule of third parties associated with the copyright material may be of relevance in determining questions of fair dealing. In respect of the Allan Border Medal excerpt, the Federal Court referred to the public embarrassment (of the Prime Minister) created by the publicising of the excerpt, and consequently rejected any argument that the use could fairly be said to be for the purpose of reporting news.[149] Similarly in respect of the Midday excerpt, Conti J’s comments that the purpose of the dealing was to satirise aspects of Ms Kennerley’s performance[150] seem inconsistent with Finkelstein J’s dissenting view in The Panel 2 that the discussion of Ms Kennerley’s ‘talents’ was newsworthy and could amount to criticism and review of the broadcast.[151] As outlined above, the comments in the Explanatory Memorandum that satire involves holding creators or performers up to scorn or ridicule suggest that these views may in fact persist in judicial determination of fairness, further increasing uncertainty for users.[152] Just as creators of copyright materials can (and should) use defamation law to protect their reputation independently of copyright protection,[153] so too can performers and others whose conduct is the target of satirical or parodic expression. The extensive economic and moral rights which are granted by the Act should be used to only to protect the object of creation and not as some broader cause of action to protect personal reputation.

The outcome of The Panel Case highlighted some of the shortcomings of Australian copyright law, particularly its inability to adapt to uses of copyright material in light entertainment programs such as The Panel. Most critically, the approach of the court to determining the question of fairness could be seen as ad hoc and unprincipled,[154] creating further uncertainty for users who may have believed their use of the material would be protected by the legislative scheme. Parody and satire received some welcome attention in the law reform process, which offered an opportunity to provide some much-needed certainty and clarity in the waters muddied by The Panel Case. This paper contends that law reform relating to parody and satire may have been dealt with more effectively by a modified version of the ‘three-step test’ outside of the existing fair dealing framework. Although such an approach would bring with it a degree of initial uncertainty, it is argued that removing parody and satire from the confines of existing copyright law frameworks would be an effective way of addressing this uncertainty, and encourage more explicit discussion of the legitimate bounds of both copyright protection and parody or satire which makes use of subject matter attracting copyright protection.

Although a novel approach to protection for parody and satire was abandoned in the law reform process, the new fair dealing provisions may provide some level of protection for creators of light entertainment. It has been argued in this paper that a judicial shift from the approach in The Panel Case is crucial to the efficacy of these provisions. The exemptions are likely to provide little assistance if they are applied as ‘questions of impression and degree’. If the fairness inquiry is conducted in a principled manner, and separately to the question of whether a use is ‘parody’ or ‘satire,’ then judicial guidelines as to what sorts of uses go beyond what is fair will emerge from the courts. But if no clear guiding principles on fairness emerge then there is a risk that undue weight may be placed on the reputation or personal feelings of copyright owners and even those objects of ridicule who have no legitimate copyright interest. This is an approach which may extend the bounds of copyright protection in an impermissible way. Furthermore, the potential for subjective value judgments to influence the outcomes of cases could stifle the creation of critical parody and satire, encouraging uncontroversial or minimalistic uses of material. This issue is compounded by uncertainty as to how to apply these provisions within the current legislative framework, particularly in their operation alongside the substantiality and moral rights provisions. This paper has contended that a provision which required express consideration of the extent to which a use conflicts with normal exploitation of the work or other subject-matter or unreasonably prejudices the legitimate interests of the copyright owner or licensee, would have reduced the impact of the subjective questions of ‘impression and degree’ inherent in the fair dealing model.

Given the commercial success of satirical television programs such as The Chaser, some of these questions may be addressed by the courts in the foreseeable future. Regrettably, it may be that a repeat of The Panel saga may be necessary before the legislature reconsiders the options of implementing fair use or flexible dealing into this area of the law. Until such an opportunity arises however, the spectre of The Panel Case will loom large in the minds of creators of light entertainment and potentially stifle creativity, an outcome which is certainly no laughing matter.

* BSc-LLB (Hons) (University of Tasmania). Law Graduate, Allens Arthur Robinson, Melbourne, < Ben.Mee@aar.com.au>.

1 TCN Channel Nine Pty Limited v Network Ten Limited [2001] FCA 108 (‘Panel 1’); TCN Channel Nine Pty Ltd v Network Ten Pty Limited [2002] FCAFC 146 (‘Panel 2’); Network Ten Pty Ltd v TCN Channel Nine [2004] HCA 14 (‘Panel 3’); TCN Channel Nine Pty Limited v Network Ten Pty Limited (No 2) [2005] FCAFC 53 (‘Panel 4’).

[2] Melissa De Zwart, ‘Australia’s Fair Dealing Exceptions: Do they Facilitate or Inhibit Creativity in the Production of Television Comedy?’ in Andrew Kenyon (ed), TV Futures: Digital Television Policy in Australia, (University of Melbourne Legal Studies Research Paper No 273, Melbourne University Press, 2007) 166, available at SSRN <http://ssrn.com/abstract=1025774> .

[3] Attorney-General’s Department, Fair Use and Other Copyright Exceptions: An Examination of Fair Use, Fair Dealing and Other Exceptions in the Digital Age, Issues Paper, (May 2005). See below at Part 4 of this paper for a discussion of the push for reform and the reform process itself.

[4] Commonwealth, Second Reading Speech, Copyright Amendment Act 2006, House of Representatives, 19 October 2006 (Philip Ruddock, Attorney-General).

[5] Contained in ss 41A, 103AA of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth).

[7] Ibid, ss 10(1), 14(1), 36, 101.

[8] ‘Audio-visual item’ is defined in s 100A to include a broadcast.

[9] Section 103A of the Act provides that the criticism or review may be of the audio-visual item, another audio-visual item or a work but sufficient acknowledgement of the audio-visual item used must be made.

[11] The leading case was the single judge decision in De Garis v Neville Jeffress Pidler Pty Ltd [1990] FCA 352; (1990) 18 IPR 292.

[13] Contained in ss 40, 103C of the Act. These factors are loosely based on the US fair use model, including the purpose of the dealing, the nature of the material used and market impact.

[14] Hubbard v Vosper [1972] 2 QB 84, 94.

[15] Panel 2 [2002] FCAFC 146, [17] (Finkelstein J).

[16] Panel 1 [2001] FCA 108, [68].

[17] Ibid, [41].

[18] Panel 2 [2002] FCAFC 146, [13] (Finkelstein J).

[19] Conti J’s findings in relation to a number of excerpts were not appealed.

[20] Panel 3 [2004] HCA 14, [79].

[21] Panel 4 [2005] FCAFC 53.

[22] See, eg, Michael Handler and David Rolph, ‘A Real Pea Souper: The Panel Case and the Development of the Fair Dealing Defences to Copyright Infringement in Australia’ [2003] MelbULawRw 15; (2003) 27 Melbourne University Law Review 381; Melissa De Zwart, ‘Seriously Entertaining: The Panel and the Future of Fair Dealing’ (2003) 8(1) Media & Arts Law Review 1.

[23] Panel 2 [2002] FCAFC 146, [22] (Finkelstein J).

[24] Panel 1 [2001] FCA 108, [72].

[25] Panel 2 [2002] FCAFC 146, [110] (Hely J).

[26] Ibid, [3] (Sundberg J).

[27] Ibid, [20] (Finkelstein J).

[28] Panel 1 [2001] FCA 108, [72].

[29] Panel 2 [2002] FCAFC 146, [122]. While this statement goes to the denial of the use as ‘news’, it may suggest that the Court inappropriately focused on the interests of a third party whose actions were targeted in the use. This is discussed further in Part 5 below.

[30] Panel 1 [2001] FCA 108, [72].

[31] Panel 2 [2002] FCAFC 146, [5] (Sundberg J), [112–113] (Hely J).

[32] Ibid, [22].

[33] Panel 4 [2005] FCAFC 53, [39].

[34] Ibid, [33].

[35] Ibid, [66].

[36] Ibid, [63].

[37] Ibid, [34].

[38] See, eg, Handler and Rolph, De Zwart, above n 22.

[39] Panel 1 [2001] FCA 108, [37].

[40] [1972] 2 QB 84, 94.

[41] Handler and Rolph, above n 22, 406.

[42] [1972] 2 QB 84, 94.

[43] The discussion of the Court essentially focuses on whether or not the purpose was news, or criticism and review with a heavy focus on the dictionary meaning of those words.

[44] Handler and Rolph, above n 22, 390.

[45] See, eg, Andrew Bock, ‘Satire is Out? They Can’t be Serious’, The Sydney Morning Herald (Sydney), 30 May 2002, 13; ‘Freedom of Speech at Risk’, The Australian Financial Review (Sydney), 30 May 2002, 62.

[46] Melissa De Zwart, ‘Fair Use? Fair Dealing?’ (2006) 24(1& 2) Copyright Reporter 20, 32.

[47] See particularly De Garis, Panel 1 [2001] FCA 108. Although the term ‘fair’ is not restricted by dictionary definitions, the extensive analysis of the meanings of each head of fair dealing arguably shifts the focus away from the question of fairness, as was seen in The Panel Case.

[48] De Zwart, above n 46, 20.

[49] Kimberlee Weatherall, ‘Locked In: Australia Gets a Bad Intellectual Property Deal’ (2004) 20(4) Policy: a Journal of Public Policy and Ideas 18, 19.

[50] For an excellent discussion of the AUSFTA process, see Catherine Bond, Abi Paramaguru and Graham Greenleaf, ‘Advance Australia Fair? The Copyright Reform Process’ (2007) 10(3/4) The Journal of World Intellectual Property 284.

[51] Weatherall, above n 49, 19.

[52] Attorney-General’s Department, above n 3, 36.

[53] Sally McCausland, ‘Protecting “A Fine Tradition of Satire”: The New Fair Dealing Exception for Parody or Satire in the Australian Copyright Act’ (2007) 29(7) European Intellectual Property Review 287, 289.

[54] Andrew Gowers, Gowers Review of Intellectual Property, (HM Treasury, London, December 2006).

[55] For a more comprehensive discussion of the Gowers Review and its implications see, eg, Peter Groves, ‘There’s Nothing New Around the Sun: Everything You Think of Has Been Done’ (2007) 18(4) Entertainment Law Review 150; D Bainbridge, ‘The Gowers Review of Intellectual Property’ (2006) 11(6) Intellectual Property & Information Technology Law 4; Hubert Best, ‘All Change’ on Copyright?’ (2007) 65 European Lawyer 9. The Attorney-General’s Office released a statement in December 2006 stating that the Gowers Review has taken the same approach as the Australian Government. See <http://www.ag.gov.au/agd/www/ministerruddockhome.nsf/Page/Media_Releases_2006_Fourth_Quarter_2332006_-10_December_2006_-_British_report_follows_Australia&apos (11 October 2007).

[56] The most significant challenge to date related to an exception in the US legislation, which allowed small businesses to play broadcast copyright musical content under defined conditions. The EU challenged the provision as being non-compliant with Article 13 and succeeded. The decision of the dispute resolution body provides much of the material used in interpreting the three-step test and is discussed in more depth later in this Part.

[57] De Zwart, above n 46, 20.

[59] Copyright Law Review Committee, Copyright and Contract, (April 2002) [3.24].

[60] Copyright Act 1911 (UK) s 2; Copyright Act 1912 (Cth) s 2.

[61] Copyright Act 1911 (UK) s 2; Copyright Act 1912 (Cth) s 2.

[62] De Zwart, above n 22, 4.

[63] (1803) 170 ER 679, 680.

[64] Pro Sieben Media A.G. v Carlton UK Television Ltd [1998] FSR 43, 49.

[65] Intellectual Property Research Institute of Australia (IPRIA) and Centre for Media and Communications Law (CMCL), Response to the Issues Paper: Fair Use and Other Copyright Exceptions in the Digital Age, (July 2005) 11.

[66] A further problem, which does not arise in relation to broadcasts, is the requirement in s 41 that the criticism or review must be of a work, which might in theory preclude the use of a work to review a film of that work.

[67] IPRIA and CMCL, above n 65, 11.

[68] Ibid.

[69] European Parliament, Directive 2001/29/EC on the Harmonisation of Certain Aspects of Copyright and Related Rights Art 5.3(d). The Directive also permits an exception for the purposes of caricature, parody or pastiche (Art 5.3(k)).

[70] Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) s 41A.

[71] Ibid, s 103AA. An audio-visual item is defined in s 100A as a sound recording, cinematograph film, sound broadcast or television broadcast.

[72] 9 F Cas. 342 (1841).

[73] Kimberlee Weatherall, ‘Fair Use, Fair Dealing: The Copyright Exceptions Review and the Future of Copyright Exceptions in Australia’, (Occasional Paper No. 3/05, IPRIA, May 2005) 8 <http://www.ipria.org/publications/workingpapers/Occasional%20Paper%203.05.pdf> .

[74] Gowers, above n 54, [4.69].

[75] Ibid, [4.68].

[76] IPRIA, above n 65, 27.

[77] De Zwart, above n 46, 31.

[78] Ibid, 33. The US approach to parody and satire will be dealt with more closely in Part 5.

[79] See, eg, Ruth Okediji, ‘Toward an International Fair Use Doctrine’ (2000) 39 Columbia Journal of Transnational Law 75, 116-117; J C Knapp, ‘Laugh and the Whole World...Scowls at You? A Defence of the United States’ Fair Use Exception for Parody Under TRIPs’ (2005) 33 Denver Journal of International Law and Policy 347.

[80] Panel Report, United States – Section 110(5) of the U.S. Copyright Act, WT/DS160/R (15 June 2000) [6.108] (‘US Fair Use Decision’).

[81] Brian Fitzgerald ‘Underlying Rationales of Fair Use: Simplifying the Copyright Act’ [1998] SCULawRw 8; (1998) 2 Southern Cross University Law Review 153.

[82] Special Broadcasting Service, Submission on Provisions of the Copyright Amendment Bill 2006, (28 October 2006)

<http://www.aph.gov.au/senate/committee/legcon_ctte/copyright06/submissions/sub33.pdf> . The submission suggested that the section be amended to make the special case requirement inapplicable to the parody and satire sub-section.

[83] Patricia Loughlan, ‘Parody, Copyright and the New Four-Step Test’ (2006) 67 Intellectual Property Forum 46, 49.

[84] Kimberlee Weatherall, ‘The (New Australian) ‘Flexible Dealings’ Exception to Copyright’ on Weatherall’s Law: IP in the land of Oz (1 July 2006) <http://weatherall.blogspot.com/2006_07_01_weatherall_archive.html#115209709458679279> .

[85] Sam Ricketson and Jane Ginsburg, International Copyright and Neighbouring Rights: The Berne Convention and Beyond (Oxford University Press, 2005) 763.

[86] US Fair Use Decision, WT/DS160/R (15 June 2000).

[87] Ibid, [6.183].

[88] Sam Ricketson, The Three-Step Test, Deemed Quantities, Libraries and Closed Exceptions (Centre for Copyright Studies, December 2002) 5.

[89] US Fair Use Decision, WT/DS160/R (15 June 2000), [6.229].

[90] Ricketson, above n 88, 5.

[91] Gowers, above n 54, [4.87].

[92] Ibid.

[93] The other exemptions in s 200AB require that the use not be partly for the purpose of obtaining a commercial advantage or profit, but the original parody and satire provision contained no such restriction.

[94] Explanatory Memorandum, Copyright Amendment Bill 2006 (Cth).

[95] Supplementary Explanatory Memorandum, Copyright Amendment Bill 2006 (Cth).

[96] EM1, above n 94, [6.53].

[97] Ibid, [6.54].

[98] As s 200AB still applies to library and educational uses, the problem may still arise.

[99] EM1, above n 94, [6.54].

[100] Ibid, [6.61].

[101] Ibid, [6.63].

[102] Although there may be some uncertainty as to the precise scope of meaning to be attributed to these terms (see below Part 5), the uncertainty is no greater than it will be with the fair dealing model.

[103] EM2, above n 95, [43].

[104] Ibid, [44].

[105] 598 F Supp 110 (ND Georgia, 1984). A discussion of this case, and the treatment of parody in the US prior to Acuff-Rose can be found in Beth Van Hecke, ‘But Seriously, Folks: Toward a Coherent Standard of Parody as Fair Use’ (1992) 77 Minnesota Law Review 465.

[106] See below Part 5 for a more comprehensive discussion of this issue.

[107] Gowers, above n 54, [4.87].

[108] De Zwart, above n 2, 7.

[109] Attorney-General’s Department, Copyright Amendment Act 2006 – Fact Sheets: New Australian Copyright Laws: Parody and Satire (31 August 2009) <http://www.ag.gov.au> .

[110] De Zwart, above n 2, 10.

[111] This was the approach taken in De Garis to interpret the terms ‘criticism’, ‘review’, ‘research’ and ‘study’. See De Garis v Neville Jeffress Pidler Pty Ltd [1990] FCA 352; (1990) 18 IPR 292.

[112] An extensive discussion of this aspect is beyond the scope of this paper but see e.g. De Zwart, above n 2; Nicholas Lewis, ‘Comment: Shades of Grey: Can the Copyright Fair Use Defense Adapt to New Re-Contextualised Forms of Music and Art?’ (2005) 55 American University Law Review 267.

[113] 510 US 569 (1994).

[114] Lewis, above n 112, 267.

[115] 510 US 569, 579 (1994).

[116] Pierre Leval, ‘Toward a Fair Use Standard’ (1990) 103 Harvard Law Review 1105, 1134.

[117] [1997] USCA9 968; 109 F 3d 1394 (9th Circuit, 1997).

[118] The hearing was for the grant of a preliminary injunction.

[119] [1997] USCA9 968; 109 F 3d 1394, 1400 (9th Circuit, 1997).

[120] De Zwart, above n 46, 26.

[121] 510 US 569, 580-1 (1994).

[122] Furthermore, it is the Fact Sheet definition of parody rather than satire which appears to apply more closely to the facts in Dr Seuss and thus this may indicate a legislative intention to move away from the US model.

[123] This was identified by Conti J in Panel 1 [2001] FCA 108, [17].

[124] 2003 US Dist LEXIS 18513, affirmed Kane v Comedy Partners, 2004 U.S. App. LEXIS 10995 (2d Cir NY, 2004).

[125] De Zwart, above n 2, 13.

[126] Panel 1 [2001] FCA 108, [17].

[127] Maree Sainsbury, ‘Parody, Satire, Honour and Reputation: The Interplay Between Economic and Moral Rights’ (2007) 18 Australian Intellectual Property Journal 149, 153.